Key Points

Question

Is lanadelumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits plasma kallikrein, effective in preventing hereditary angioedema attacks?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial involving 125 patients with hereditary angioedema type I or II, treatment with lanadelumab for 26 weeks significantly reduced the mean attack rate (0.26-0.53 attacks/month) compared with placebo (1.97 attacks/month).

Meaning

These findings support the use of lanadelumab for the prevention of hereditary angioedema attacks.

Abstract

Importance

Current treatments for long-term prophylaxis in hereditary angioedema have limitations.

Objective

To assess the efficacy of lanadelumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody that selectively inhibits active plasma kallikrein, in preventing hereditary angioedema attacks.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Phase 3, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial conducted at 41 sites in Canada, Europe, Jordan, and the United States. Patients were randomized between March 3, 2016, and September 9, 2016; last day of follow-up was April 13, 2017. Randomization was 2:1 lanadelumab to placebo; patients assigned to lanadelumab were further randomized 1:1:1 to 1 of the 3 dose regimens. Patients 12 years or older with hereditary angioedema type I or II underwent a 4-week run-in period and those with 1 or more hereditary angioedema attacks during run-in were randomized.

Interventions

Twenty-six-week treatment with subcutaneous lanadelumab 150 mg every 4 weeks (n = 28), 300 mg every 4 weeks (n = 29), 300 mg every 2 weeks (n = 27), or placebo (n = 41). All patients received injections every 2 weeks, with those in the every-4-week group receiving placebo in between active treatments.

Main Outcome and Measures

Primary efficacy end point was the number of investigator-confirmed attacks of hereditary angioedema over the treatment period.

Results

Among 125 patients randomized (mean age, 40.7 years [SD, 14.7 years]; 88 females [70.4%]; 113 white [90.4%]), 113 (90.4%) completed the study. During the run-in period, the mean number of hereditary angioedema attacks per month in the placebo group was 4.0; for the lanadelumab groups, 3.2 for the every-4-week 150-mg group; 3.7 for the every-4-week 300-mg group; and 3.5 for the every-2-week 300-mg group. During the treatment period, the mean number of attacks per month for the placebo group was 1.97; for the lanadelumab groups, 0.48 for the every-4-week 150-mg group; 0.53 for the every-4-week 300-mg group; and 0.26 for the every-2-week 300-mg group. Compared with placebo, the mean differences in the attack rate per month were −1.49 (95% CI, −1.90 to −1.08; P < .001); −1.44 (95% CI, −1.84 to −1.04; P < .001); and −1.71 (95% CI, −2.09 to −1.33; P < .001). The most commonly occurring adverse events with greater frequency in the lanadelumab treatment groups were injection site reactions (34.1% placebo, 52.4% lanadelumab) and dizziness (0% placebo, 6.0% lanadelumab).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients with hereditary angioedema type I or II, treatment with subcutaneous lanadelumab for 26 weeks significantly reduced the attack rate compared with placebo. These findings support the use of lanadelumab as a prophylactic therapy for hereditary angioedema. Further research is needed to determine long-term safety and efficacy.

Trial Registration

EudraCT Identifier: 2015-003943-20; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02586805

This randomized clinical trial compares the ability of lanadelumab—a human monoclonal antibody that selectively inhibits active plasma kallikrein—vs placebo to prevent angioedema among patients with types I and II hereditary angioedema.

Introduction

Hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency is a rare autosomal dominant disorder due to C1 inhibitor deficiency (type I) or dysfunction (type II) that leads to dysregulated plasma kallikrein activity, excess bradykinin production, and unpredictable potentially life-threatening recurrent angioedema attacks.1,2 Patients with hereditary angioedema are often limited in their ability to perform daily activities at work, school, or home; experience symptoms of anxiety and depression; face a risk of asphyxiation due to laryngeal attacks; and report poor health-related quality of life.3,4,5

Currently available prophylactic therapeutic options have important limitations. Oral androgens may have substantial adverse effects that may require close monitoring.6,7 Intravenous C1 inhibitor treatment is limited by venous access issues and complications of indwelling ports. Subcutaneous C1 inhibitor treatment with higher doses may require larger volumes than typical for subcutaneous injections.8 Both intravenous and subcutaneous administration require frequent administration every 3 to 4 days.8,9,10 Furthermore, antifibrinolytics have demonstrated minimal efficacy.11 Thus, there remains an unmet need in the management of hereditary angioedema for an effective, well-tolerated, conveniently administered, long-acting prophylactic therapy.5

Lanadelumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody that binds and inhibits active plasma kallikrein, thereby preventing the cleavage of high-molecular-weight kininogen and the generation of bradykinin.12,13 Lanadelumab does not inhibit the tissue kallikrein-kinin system, which maintains bradykinin levels for important physiological and cardiovascular functions.13 In a phase 1b study, lanadelumab was well tolerated and significantly inhibited proteolysis of high-molecular-weight kininogen in a dose-dependent manner and was associated with reductions in hereditary angioedema attacks.12,14,15 The objective of the Hereditary Angioedema Long-term Prophylaxis (HELP) clinical trial was to determine the efficacy of lanadelumab compared with placebo for preventing hereditary angioedema attacks.

Methods

Trial Design and Oversight

The study was conducted in accordance with International Conference on Harmonisation of Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki,16 as well as other applicable local ethical and legal requirements. All patients or caregivers provided written informed consent (or assent from patients <18 years) at screening. An independent data and safety monitoring board provided oversight, including review and assessment of unblinded study data (Trial Protocol in Supplement 1).

This was a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial at 41 sites in Canada, Europe, Jordan, and the United States that evaluated the efficacy, adverse events, and other safety parameters of subcutaneously administered lanadelumab in preventing hereditary angioedema attacks. The original protocol and the statistical analysis plan for this study are available (Supplement 1). At the end of the 26-week treatment period, patients could enter either an open-label extension study (HELP Study Extension, NCT02741596)17 or an 8-week safety follow-up (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2).

Patient Enrollment

Patients were 12 years or older at screening with a confirmed diagnosis of hereditary angioedema type I or II (See eMethods 1 in Supplement 2 for full inclusion and exclusion criteria.) Race/ethnicity data were self-reported by patients using fixed categories and collected by qualified staff at each site in accordance with US Food and Drug Administration regulations. Patients underwent a 4-week run-in period (preceded by a ≥2-week washout of any long-term prophylactic therapy if applicable) to determine their baseline attack rate. Patients with 1 or more investigator-confirmed attack per 4 weeks were eligible for enrollment (eMethods 2 in Supplement 2). The study was powered to compare effects of lanadelumab vs placebo but was not designed or powered to compare the effects of the 3 lanadelumab groups.

Study Treatment Protocol

Patients, caregivers of patients younger than 18 years, investigators, site personnel, and the sponsor were blinded to study treatment until the study was complete. Eligible patients were randomized 2:1 to receive subcutaneously injected lanadelumab or placebo. Patients randomized to receive lanadelumab were assigned in a 1:1:1 ratio to 1 of 3 lanadelumab dose regimens: 150 mg every 4 weeks, 300 mg every 4 weeks, or 300 mg every 2 weeks (Figure 1). All patients received injections every 2 weeks, with those in the every-4-week groups receiving placebo in between active treatments. Patients were enrolled and assigned to interventions using an interactive web-based randomization system (Rho Inc) by blinded study staff in the order of enrollment. Randomization was stratified by normalized number of attacks during the run-in period: 1 to less than 2, 2 to less than 3, or 3 or more attacks within 4 weeks using a within-stratum block size of 9. Patients who experienced 3 or more investigator-confirmed attacks before the end of the 4 weeks may have exited the run-in period early and proceeded to enrollment and randomization. Patients without 1 or more investigator-confirmed attack after 4 weeks of run-in may have extended their run-in for another 4 weeks, during which time they needed to have 2 or more investigator-confirmed attacks to proceed to enrollment and randomization. Attack rates were normalized to the number of attacks over 4 weeks (28 days). Because patients may have had their run-in period shortened or extended, noninteger values were possible. Each patient received 13 doses of blinded study drug over the 26-week treatment period (days 0-182). Lanadelumab was provided as a 150-mg/mL solution, formulated as described previously.14,15 To maintain the blind, all patients received 2 injections of the study drug administered in the same upper arm (see eMethods 3 in Supplement 2).

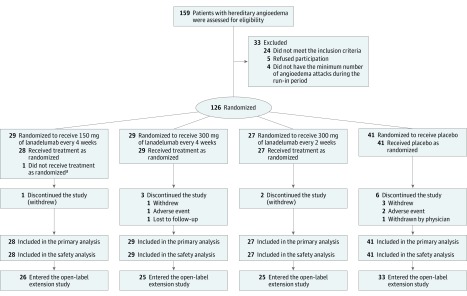

Figure 1. Flowchart of Study Enrollment in a Trial of Lanadelumab for Hereditary Angioedema.

All patients received injections every 2 weeks, with those in the every-4-week groups receiving placebo in between active treatments.

aOne patient was determined to be a screen failure after randomization to the group that received 150 mg of lanadelumab every 4 weeks. This patient was not treated and was withdrawn from the study. This patient was counted in the randomized population but was excluded from both the intent-to-treat and safety populations.

Treatment of attacks followed the site investigator’s standard of care, which could include intravenous C1 inhibitor, icatibant, or ecallantide. Long-term prophylaxis, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, exogenous estrogens, and other investigational products were prohibited during the study. Short-term prophylaxis for procedures was permitted if medically indicated.

Outcome Measures

All hereditary angioedema attacks analyzed for the primary, secondary, and exploratory end points were investigator confirmed. Patients notified and reported details to the study site within 72 hours of the onset of a hereditary angioedema attack. The primary efficacy end point was the number of attacks during the 26-week treatment period. Secondary end points included the number of attacks requiring acute treatment during the 26-week treatment period, number of moderate or severe18 attacks (eMethods 4 in Supplement 2) during the 26-week treatment period, and number of attacks from days 14 through 182. Additional prespecified exploratory end points included the percentage of patients who were attack-free, number of attack-free days, responders, and number of high-morbidity attacks. An attack-free day was defined as a calendar day with no investigator-confirmed attack. Any patient who achieved at least a prespecified reduction in attack rate relative to baseline was defined as a responder; responder thresholds included reductions of 50% or more, 70% or more, and 90% or more. A high-morbidity attack was defined as any attack that was severe, laryngeal, hemodynamically significant, or resulted in hospitalization. Maximum attack severity (attack free, mild, moderate, or severe), attack location, attack duration, and on-demand medication use to treat attacks also were evaluated. Prespecified subgroup analyses were conducted based on hereditary angioedema disease or patient characteristics including long-term prophylaxis use before study entry, run-in period attack rate, sex, and body mass index. The attack rates and percentage of patients attack-free during a 16-week steady-state period (days 70-182, based on an observed lanadelumab half-life of 14 days14) were compared across treatment groups in a post hoc analysis. Health–related quality of life was assessed using the Angioedema Quality of Life Questionnaire, a validated, self-administered, angioedema-specific quality of life instrument. Scores range from 0 to 100 with lower scores indicating lower impairment (ie, higher health–related quality of life); the minimal clinically important difference for the total score is 6.19,20

Adverse Events and Antidrug Antibodies

Adverse events following repeated subcutaneous lanadelumab administrations were analyzed. Adverse events were captured over the entire treatment period (eMethods 4 in Supplement 2). Although attacks also were captured as adverse events, they are summarized only in the efficacy analysis. The presence of antidrug antibodies was assessed by previously described methods,14 and positive samples were further analyzed for the presence of neutralizing antibodies.14

Statistical Analysis

Up to 120 patients were planned for enrollment to provide 108 patients who completed the study. A sample size of 24 patients for each active treatment group (72 patients total) and 36 patients in the placebo group provided 95% or more power (1-sided α = .025; active treatment group to placebo ratio set at 1:1.5; 10% missing data) to detect a treatment effect of 60% or more reduction in hereditary angioedema attacks compared with placebo, assuming a placebo attack rate of 0.3 per week. This sample size was based on simulations using a generalized linear model for count data assuming a Poisson distribution with Pearson χ2 scaling of SEs to account for potential overdispersion. A reduction of 60% or more is a good estimate of the treatment effect that might be seen based on previous prophylactic studies conducted in hereditary angioedema; a 12-week study with C1-inhibitor treatment showed a reduction of approximately 50% in the number of attacks compared with placebo.9 This study was powered to compare effects of lanadelumab vs placebo but was neither designed nor powered to compare the effects of the 3 lanadelumab groups

All efficacy analyses were conducted using the intent-to-treat population, defined as all randomized patients exposed to study treatment; analyses were performed according to patients’ randomized treatment assignment. Adverse event analyses were conducted using the safety population, which included all patients who received 1 or more dose of study treatment; analyses were performed according to the actual treatment received.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). eMethods 5 in Supplement 2 provides a detailed description of statistical methods. The primary and secondary efficacy end points for each active treatment group were compared with the placebo group using a Poisson regression model including a covariate for the normalized run-in period attack rate and accounting for potential overdispersion, with the overall type I error controlled at .05. A post hoc analysis that included region (United States vs non-United States) as a categorical covariate was also conducted. To adjust for the potential of an inflated overall type I error rate due to multiple comparisons, the primary end point and rank-ordered secondary end points were tested in a fixed sequence for each lanadelumab treatment group vs the placebo group comparison at a 1.67% significance level (α/3; 2-sided). All available data were included in the primary and secondary efficacy analyses. The logarithm of the number of days a patient was observed during the treatment period was included as an offset variable in the generalized linear model to adjust for differences in follow-up time. A tipping-point analysis was conducted to measure the potential effect of missing data on the reliability of the primary efficacy analysis. The observed portion of the treatment period was used for the analysis of binary outcomes. Exploratory binary and continuous end points for each lanadelumab treatment group were compared with the placebo group without adjustment for multiplicity, using Fisher exact test and t test, respectively.

Results

A total of 125 patients were randomized and treated (placebo, n = 41; lanadelumab, n = 84), and 113 (90.4%) completed the study; the majority (109 of 113; 96.5%) entered the open-label extension17 (Figure 1). Of the 12 patients who did not complete the study, 6 received placebo and 6 received lanadelumab. eTable 2 in Supplement 2 details treatment duration for each patient who discontinued.

Patient Characteristics

The mean (SD) age among all patients was 40.7 years (14.7 years), 90.4% were white, and 70.4% were female (Table 1). More than half of the patients in both the placebo and lanadelumab groups (58.5% and 54.8%, respectively) reported treatment with long-term prophylaxis in the 3 months before screening. Patients reported a mean of 3.7 attacks per month during the run-in period. A total of 65 patients (52.0%) reported 3 or more attacks per month during the run-in period. On average, 99.4% of blinded study drug doses were received per protocol.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristicsa.

| Characteristics | No. (%) of Patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lanadelumab | Placebo (n = 41) | |||

| Every 4 Weeks | 300 mg Every 2 Weeks (n = 27) | |||

| 150 mg (n = 28) | 300 mg (n = 29) | |||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 43.4 (14.9) | 39.5 (12.8) | 40.3 (13.3) | 40.1 (16.8) |

| <18 | 1 (3.6) | 3 (10.3) | 2 (7.4) | 4 (9.8) |

| 18 to <65 | 24 (85.7) | 26 (89.7) | 25 (92.6) | 35 (85.4) |

| ≥65 | 3 (10.7) | 0 | 0 | 2 (4.9) |

| Females | 20 (71.4) | 19 (65.5) | 15 (55.6) | 34 (82.9) |

| Males | 8 (28.6) | 10 (34.5) | 12 (44.4) | 7 (17.1) |

| Raceb | ||||

| White | 25 (89.3) | 23 (79.3) | 26 (96.3) | 39 (95.1) |

| Black | 1 (3.6) | 6 (20.7) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (4.9) |

| Asian | 2 (7.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| BMI, mean (SD)c | 26.9 (4.7) | 28.1 (5.1) | 31.0 (7.8) | 27.5 (7.7) |

| Hereditary angioedema type | ||||

| Type I | 25 (89.3) | 27 (93.1) | 23 (85.2) | 38 (92.7) |

| Type II | 3 (10.7) | 2 (6.9) | 4 (14.8) | 3 (7.3) |

| Age at symptom onset, mean (SD), y | 12.0 (8.8) | 14.6 (11.2) | 15.0 (8.7) | 11.2 (8.2) |

| History of laryngeal attacks | 17 (60.7) | 17 (58.6) | 20 (74.1) | 27 (65.9) |

| No. of attacks in 12 mo before screening, median (IQR) | 34 (12-55) | 24 (12-50) | 20 (8-36) | 30 (17-59) |

| Use of long-term prophylaxis in 3 mo before screening | ||||

| Plasma-derived C1 inhibitord | 9 (32.1) | 18 (62.1) | 11 (40.7) | 22 (53.7) |

| Oral therapye | 2 (7.1) | 1 (3.4) | 0 | 1 (2.4) |

| Combination therapyf | 1 (3.6) | 1 (3.4) | 3 (11.1) | 1 (2.4) |

| No prophylaxis | 16 (57.1) | 9 (31.0) | 13 (48.1) | 17 (41.5) |

| Run-in hereditary angioedema attack rate, mean (SD), attacks per mog | 3.2 (1.8) | 3.7 (2.5) | 3.5 (2.3) | 4.0 (3.3) |

| Normalized run-in attack rate category, attacks per moh,i | ||||

| 1-<2 | 10 (35.7) | 9 (31.0) | 7 (25.9) | 12 (29.3) |

| 2-<3 | 3 (10.7) | 5 (17.2) | 6 (22.2) | 8 (19.5) |

| ≥3 | 15 (53.6) | 15 (51.7) | 14 (51.9) | 21 (51.2) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

All patients received injections every 2 weeks, with those in the every-4-week groups receiving placebo in between active treatments.

Race/ethnicity data were self-reported by patients using fixed categories and collected by qualified staff at each site per US Food and Drug Administration regulations for sponsors of New Drug Applications.

Body mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Includes patients who used only plasma-derived C1 inhibitor.

Incudes patients who used only oral therapy, which includes androgens and antifibrinolytics.

Patients using both C1 inhibitor and oral therapy for long-term prophylaxis.

Month was defined as 28 days.

The length of the run-in period was 4 weeks. Patients who experienced 3 or more investigator-confirmed attacks before the end of the 4 weeks may have exited the run-in period early and proceeded to enrollment and randomization. Patients without 1 or more investigator-confirmed attack after 4 weeks of run-in may have extended their run-in for another 4 weeks, during which time they needed to have 2 or more investigator-confirmed attacks to proceed to enrollment and randomization. eTable 3 in Supplement 2 summarizes the duration of run-in for patients in each treatment group. Attack rates were normalized to the number of attacks over 4 weeks. Because patients may have had their run-in period shortened or extended, noninteger values were possible.

eTable 4 in Supplement 2 provides a more specific breakdown of the number of patients by run-in attack rate category.

Efficacy

Primary End Point

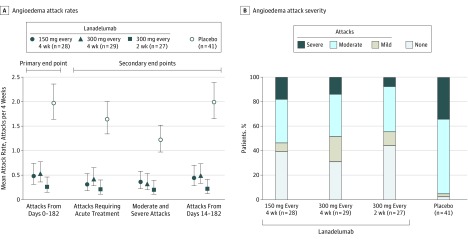

During the run-in period, the mean attack rate ranged from 3.2 to 4.0 attacks per month across the 4 treatment groups. All lanadelumab treatment regimens were more effective than placebo for the primary end point. The model-based mean number of attacks per month from days 0 through 182 was 1.97 (95% CI, 1.64-2.36) in the placebo group compared with 0.48 (95% CI, 0.31-0.73) in the 150-mg every-4-week group, 0.53 (95% CI, 0.36-0.77) in the 300-mg every-4-week group, and 0.26 (95% CI, 0.14-0.46) in the 300-mg every-2-week group (Figure 2, A). There were statistically significant reductions in attack rates per month; the mean difference in the lanadelumab groups vs the placebo group was −1.49 (95% CI, −1.90 to −1.08) in the 150-mg every-4-week group, −1.44 (95% CI, −1.84 to −1.04) in the 300-mg every-4-week group, and −1.71 (95% CI, −2.09 to −1.33) in the 300-mg every-2-week group (adjusted P < .001 for all comparisons). The mean rate ratio relative to placebo was 0.24 (95% CI, 0.15 to 0.39) for the 150-mg every-4-week group, 0.27 (95% CI, 0.18 to 0.41) for the 300-mg every-4-week group, and 0.13 (95% CI, 0.07 to 0.24) for the 300-mg every-2-week group (adjusted P < .001 for all comparisons). The mean attack rate over the treatment period by month and by treatment group is shown in eFigure 2 in Supplement 2.

Figure 2. Primary and Secondary Efficacy End Points and Maximum Severity of Investigator-Confirmed Hereditary Angioedema Attacks From Days 0-182.

All patients received injections every 2 weeks, with those in the every-4-week groups receiving placebo in between active treatments.

A, Attack rates are model-based mean attacks per month, with a month defined as 4 weeks. The mean attack rate for each group is presented with error bars representing 95% CI.

B, Maximum hereditary angioedema attack severity is the most severe attack reported by the patient. For patients who did not complete the study, all available data were used for classification.

Secondary End Points

The rate ratio for each lanadelumab group relative to placebo showed a statistically significant reduction in attack rates for all rank-ordered secondary efficacy analyses (adjusted P < .001 for all comparisons). For attacks requiring acute treatment, the mean per month difference in lanadelumab vs placebo was −1.32 (95% CI, −1.69 to −0.95) for the 150-mg every-4-week group, −1.21 (95% CI, −1.58 to −0.85) for the 300-mg every-4-week group, and −1.43 (95% CI, −1.78 to −1.07) for the 300-mg every-2-week group. For moderate or severe attacks, the mean difference vs placebo was −0.86 (95% CI, −1.18 to −0.53) for the 150-mg every-4-week group, −0.89 (95% CI, −1.20 to −0.58) for the 300-mg every-4-week group, and −1.01 (95% CI, −1.32 to −0.71) for the 300-mg every-2-week group. For attacks from days 14 through 182, the mean difference vs placebo was −1.54 (95% CI, −1.96 to −1.12) for the 150-mg every-4-week group, −1.50 (95% CI, −1.91 to −1.09) for the 300-mg every-4-week group, and −1.77 (95% CI, −2.16 to −1.38) for the 300-mg every-2-week group (Table 2 and Figure 2, A).

Table 2. Primary and Secondary Outcomes Among Patients With Hereditary Angioedema Attacks Taking Lanadelumab vs Placeboa.

| Lanadelumab | Placebo (n = 41) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Every 4 Weeks | 300 mg Every 2 Weeks (n = 27) | |||

| 150 mg (n = 28) | 300 mg (n = 29) | |||

| Primary End Point | ||||

| No. of attacks per mo, d 0-182 | ||||

| Mean (95% CI)b,c | 0.48 (0.31 to 0.73) | 0.53 (0.36 to 0.77) | 0.26 (0.14 to 0.46) | 1.97 (1.64 to 2.36) |

| Difference (95% CI)d | −1.49 (−1.90 to −1.08) | −1.44 (−1.84 to −1.04) | −1.71 (−2.09 to −1.33) | |

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Rate ratio (95% CI)c | 0.24 (0.15 to 0.39) | 0.27 (0.18 to 0.41) | 0.13 (0.07 to 0.24) | |

| P valuee | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Secondary End Points | ||||

| No. of attacks requiring acute treatment per mo, d 0-182 | ||||

| Mean (95% CI)b,c | 0.31 (0.18 to 0.53) | 0.42 (0.28 to 0.65) | 0.21 (0.11 to 0.40) | 1.64 (1.34 to 2.00) |

| Difference (95% CI)d | −1.32 (−1.69 to −0.95) | −1.21 (−1.58 to −0.85) | −1.43 (−1.78 to −1.07) | |

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Rate ratio (95% CI)c | 0.19 (0.11 to 0.34) | 0.26 (0.16 to 0.41) | 0.13 (0.07 to 0.25) | |

| P valuee | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| No. of moderate or severe attacks per mo, d 0-182 | ||||

| Mean (95% CI)b,c | 0.36 (0.22 to 0.58) | 0.32 (0.20 to 0.53) | 0.20 (0.11 to 0.39) | 1.22 (0.97 to 1.52) |

| Difference (95% CI)d | −0.86 (−1.18 to −0.53) | −0.89 (−1.20 to −0.58) | −1.01 (−1.32 to −0.71) | |

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Rate ratio (95% CI)c | 0.30 (0.17 to 0.50) | 0.27 (0.16 to 0.46) | 0.17 (0.08 to 0.33) | |

| P valuee | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| No. of attacks per mo, d 14-182 | ||||

| Mean (95% CI)b,c | 0.44 (0.28 to 0.70) | 0.49 (0.33 to 0.73) | 0.22 (0.12 to 0.41) | 1.99 (1.65 to 2.39) |

| Difference (95% CI)d | −1.54 (−1.96 to −1.12) | −1.50 (−1.91 to −1.09) | −1.77 (−2.16 to −1.38) | |

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Rate ratio (95% CI)c | 0.22 (0.14 to 0.36) | 0.25 (0.16 to 0.38) | 0.11 (0.06 to 0.21) | |

| P valuee | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

All patients received injections every 2 weeks, with those in the every-4-week groups receiving placebo in between active treatments.

Attack rates are model-based mean attacks per month, defined as 4 weeks.

Results are from a Poisson regression model accounting for overdispersion; treatment group and normalized baseline attack rate were fixed effects. The logarithm of time (days) each patient was observed during the treatment period was an offset variable. All P values (Wald test) reported vs placebo.

Estimated from a nonlinear function of the model parameters. All P values (Wald test) reported vs placebo.

P value adjusted for multiple testing.

Prespecified Exploratory End Points

Over the 26-week treatment period, for patients in all 3 lanadelumab treatment groups, a significantly greater proportion of patients were attack free (39.3% in the 150-mg every-4-week group; P < .001; 31.0% in the 300-mg every-4-week group; P = .001; and 44.4% in the 300-mg every-2-week group; P < .001) compared with placebo (2.4%; Figure 2, B). There were also significantly more attack-free days per month (26.9 in the 150-mg every-4-week group, P < .001; 26.9 in the 300-mg every-4-week group, P < .001; and 27.3 in the 300-mg every-2-week group, P < .001) vs placebo (22.6; Table 3). Over the 26-week treatment period, 89.3% in the 150-mg every-4-week group (P < .001) and 100% in both the 300-mg every-4-week and 300-mg every-2-week groups (P < .001 for both) treated with lanadelumab had a reduction in attack rate from the run-in period of 50% or more compared with 31.7% of patients in the placebo group. Reductions of 70% or more and 90% or more were observed in 75.9% to 88.9% and 55.2% to 66.7% of patients treated with lanadelumab (P < .001 for all) compared with 9.8% and 4.9% of patients in the placebo group, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3. Exploratory End Points Among Patients With Hereditary Angioedema Attacks Taking Lanadelumab vs Placeboa.

| Lanadelumab | Placebo (n = 41) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Every 4 Weeks | 300 mg Every 2 Weeks (n = 27) | |||

| 150 mg (n = 28) | 300 mg (n = 29) | |||

| Responder analysis, No. (%)b | ||||

| ≥50% Reduction | 25 (89.3) | 29 (100) | 27 (100) | 13 (31.7) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 57.6 (35.2 to 75.5) | 68.3 (48.1 to 82.9) | 68.3 (47.9 to 83.8) | |

| P valuec | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| ≥70% Reduction | 22 (78.6) | 22 (75.9) | 24 (88.9) | 4 (9.8) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 68.8 (48.0 to 84.1) | 66.1 (45.2 to 82.1) | 79.1 (60.0 to 91.6) | |

| P valuec | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| ≥90% Reduction | 18 (64.3) | 16 (55.2) | 18 (66.7) | 2 (4.9) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 59.4 (37.9 to 76.7) | 50.3 (27.7 to 68.8) | 61.8 (39.5 to 78.8) | |

| P valuec | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Maximum attack severity, No. (%) | ||||

| Attack free | 11 (39.3) | 9 (31.0) | 12 (44.4) | 1 (2.4) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 36.8 (13.1 to 57.5) | 28.6 (5.0 to 50.0) | 42.0 (18.1 to 61.8) | |

| P valuec | <.001 | .001 | <.001 | |

| Mild | 2 (7.1) | 6 (20.7) | 3 (11.1) | 1 (2.4) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 4.7 (−19.3 to 27.9) | 18.3 (−5.4 to 40.6) | 8.7 (−15.6 to 32.0) | |

| P valuec | .56 | .02 | .29 | |

| Moderate | 10 (35.7) | 10 (34.5) | 10 (37.0) | 25 (61.0) |

| Difference (95% CI) | −25.3 (−47.2 to −0.9) | −26.5 (−48.2 to −2.5) | −23.9 (−46.7 to 0.7) | |

| P valuec | .05 | .05 | .08 | |

| Severe | 5 (17.9) | 4 (13.8) | 2 (7.4) | 14 (34.1) |

| Difference (95% CI) | −16.3 (−39.1 to 7.8) | −20.4 (−42.5 to 3.5) | −26.7 (−48.9 to −2.8) | |

| P valuec | .18 | .09 | .02 | |

| Attack-free d per mo, mean (SD), d | 26.9 (1.6) | 26.9 (1.3) | 27.3 (1.3) | 22.6 (4.4) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 4.3 (2.7 to 5.8) | 4.3 (2.8 to 5.8) | 4.7 (3.2 to 6.2) | |

| P valued | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| No. high-morbidity attacks per mo | ||||

| Mean (95% CI)e,f | 0.05 (0.01 to 0.15) | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.12) | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.13) | 0.22 (0.14 to 0.35) |

| Difference (95% CI)g | −0.17 (−0.29 to −0.06) | −0.19 (−0.30 to −0.08) | −0.19 (−0.30 to −0.07) | |

| P value | .004 | <.001 | .001 | |

| Rate ratio (95% CI)f | 0.21 (0.06 to 0.75) | 0.14 (0.03 to 0.58) | 0.15 (0.04 to 0.65) | |

| P value | .02 | .007 | .01 | |

P values shown for exploratory end points were not adjusted for multiplicity. All patients received injections every 2 weeks, with those in the every-4-week groups receiving placebo in between active treatments.

Achievement of a prespecified reduction from the run-in period in the hereditary angioedema attack rate. The percentage reduction was calculated as the run-in period attack rate minus the treatment period attack rate divided by the run-in period attack rate, multiplied by 100.

The difference vs placebo was analyzed using Fisher exact test.

The difference vs placebo was analyzed using a t test.

Attack rates are model-based mean attacks per month, defined as 4 weeks.

Results are from a Poisson regression model accounting for overdispersion; treatment group and the normalized baseline attack rate were fixed effects. The logarithm of time (days) each patient was observed during the treatment period was an offset variable. All P values (Wald test) reported vs placebo.

Estimated from a nonlinear function of the model parameters. All P values (Wald test) reported vs placebo.

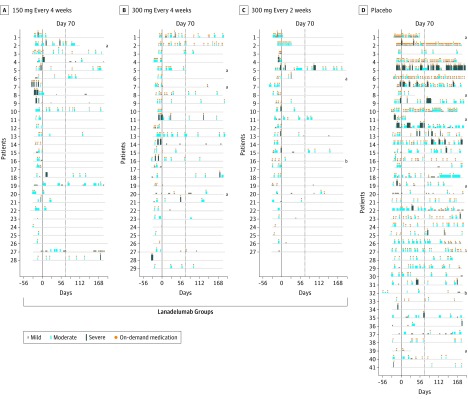

All attacks, including severity, duration, and use of on-demand treatment, are depicted for each patient in Figure 3. Primary attack location and attack duration are summarized in eTable 5 and eTable 6 in Supplement 2, respectively. Overall, 20.2% of patients who received lanadelumab used intravenous C1-inhibitor on-demand medication during the treatment period compared with 65.9% of patients who received placebo (see eTable 7 in Supplement 2). There was a significant reduction in the rate of high-morbidity attacks following lanadelumab treatment (mean difference vs placebo range, −0.19 to −0.17 attacks per month; Table 3). The treatment effect was consistent in patients regardless of whether prior long-term prophylaxis was used, the run-in attack rate category, and patient sex and body mass index (eTable 8 in Supplement 2).

Figure 3. Overview of Investigator-Confirmed Hereditary Angioedema Attacks and Use of On-Demand Medication.

Each horizontal line represents data for an individual patient. Profiles are presented in order by the attack rate during the run-in period. The width of the blue boxes indicates the duration of the attack and the height indicates the severity of the attack. Orange circles indicate the use of on-demand medication. The dotted line at day 70 represents the start of steady state (days 70-182). The solid line represents end of the run-in period. All patients received injections every 2 weeks, with those in the every-4-week groups receiving placebo in between active treatments.

aDiscontinued the study and did not complete the treatment period.

bDiscontinued the study but completed the treatment period. See eTable 2 in Supplement 2 for a summary of treatment duration for patients who did not complete the study and reasons for discontinuation.

The results of the tipping-point analysis suggested that missing data did not affect the findings; the postdiscontinuation hereditary angioedema attack rate would have needed to be 27, 22, and 35 times as high as observed during the study for the 3 lanadelumab treatment groups, respectively, to reverse the significance finding over placebo (eTable 9 in Supplement 2). The inclusion of geographical region in the statistical model also did not change the findings (P = .41 for United States vs non-United States countries). The rate ratios in this model were comparable with the ratios in the main model (eTables 10 and 11 in Supplement 2).

Post Hoc Sensitivity Analysis

During the steady-state period (days 70-182), there was a significant reduction in the monthly attack rate following lanadelumab treatment: difference vs placebo was −1.46 (95% CI, −1.89 to −1.03 for the 150-mg every-4-week group; P < .001), −1.52 (95% CI, −1.93 to −1.11 for the 300-mg every-4-week group; P < .001), and −1.72 (95% CI, −2.12 to −1.33 for the 300-mg every-2-week group; P < .001; Table 4). The proportion of patients with severe attacks also was lower in patients treated with lanadelumab (3.6% [P = .02] in the 150-mg every-4-week group, 6.9% [P = .05] in the 300-mg every-4-week group, and 3.8% [P = .02] in the 300-mg every-4-week group) compared with placebo (27.0%). Furthermore, 1 patient (2.7%) from the placebo group was attack free during the steady state period compared with 15 patients (53.6%) in the 150-mg every-4-week group, 13 (44.8%) in the 300-mg every-4-week group, and 20 (76.9%) in the 300-mg every-2-week group (P < .001 for all lanadelumab groups vs placebo).

Table 4. Post Hoc End Points and Health–Related Quality of Life Among Patients With Hereditary Angioedema Attacks Taking Lanadelumab vs Placeboa.

| Lanadelumab | Placebo (n = 41) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Every 4 Weeks | 300 mg Every 2 Weeks (n = 27) | |||

| 150 mg (n = 28) | 300 mg (n = 29) | |||

| Post hoc End Pointsb | ||||

| Attacks per mo during steady statec | ||||

| No. of Patients | 28 | 29 | 26 | 37 |

| Mean (95% CI)d,e | 0.42 (0.26 to 0.68) | 0.37 (0.22 to 0.60) | 0.16 (0.07 to 0.35) | 1.88 (1.54 to 2.30) |

| Difference (95% CI)f | −1.46 (−1.89 to −1.03) | −1.52 (−1.93 to −1.11) | −1.72 (−2.12 to −1.33) | |

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Rate ratio (95% CI)e | 0.22 (0.13 to 0.38) | 0.19 (0.12 to 0.33) | 0.09 (0.04 to 0.19) | |

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Maximum attack severity during steady state, No. (%)c | ||||

| Attack free | 15 (53.6) | 13 (44.8) | 20 (76.9) | 1 (2.7) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 50.9 (28.0 to 69.9) | 42.1 (18.6 to 62.2) | 74.2 (53.6 to 88.6) | |

| P valueg | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Mild | 3 (10.7) | 4 (13.8) | 2 (7.7) | 2 (5.4) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 5.3 (−19.0 to 29.3) | 8.4 (−16.0 to 31.7) | 2.3 (−22.6 to 26.9) | |

| P valueg | .64 | .39 | >.99 | |

| Moderate | 9 (32.1) | 10 (34.5) | 3 (11.5) | 24 (64.9) |

| Difference (95% CI) | −32.7 (−54.3 to −8.0) | −30.4 (−52.2 to −5.9) | −53.3 (−72.1 to −29.8) | |

| P valueg | .01 | .03 | <.001 | |

| Severe | 1 (3.6) | 2 (6.9) | 1 (3.8) | 10 (27.0) |

| Difference (95% CI) | −23.5 (−45.9 to 1.2) | −20.1 (−42.9 to 4.2) | −23.2 (−46.3 to 2.1) | |

| P valueg | .02 | .05 | .02 | |

| Health–Related Quality of Life | ||||

| No. of patients | 26 | 27 | 26 | 38 |

| Change in total score, from d 0-182, mean (95% CI)h | –19.82 (−26.76 to −12.88) | –17.38 (−24.17 to −10.58) | –21.29 (−28.21 to −14.37) | –4.72 (−10.46 to 1.02) |

| P valuei | ||||

| Change vs placebo, mean (95% CI) | −15.11 (−27.12 to −3.09) | −12.66 (−24.51 to −0.80) | −16.57 (−28.53 to −4.62) | |

| P valuej | .008 | .03 | .003 | |

| Responded to therapy, %k | 65.38 | 62.96 | 80.77 | 36.84 |

| P value | .047 | .07 | .001 | |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 3.24 (1.14 to 9.19) | 2.91 (1.05 to 8.10) | 7.20 (2.22 to 23.37) | |

| P value | .03 | .04 | .001 | |

All patients received injections every 2 weeks, with those in the every-4-week groups receiving placebo in between active treatments.

P values shown for exploratory end points were not adjusted for multiplicity.

The 16-week steady state period included days 70 through 182.

Attack rates are model-based mean attacks per month, with a month defined as 4 weeks.

Results are from a Poisson regression model accounting for overdispersion; treatment group and normalized baseline attack rate were fixed effects. The logarithm of time (days) each patient was observed during the treatment period was an offset variable. All P values (Wald test) reported vs placebo.

Estimated from a nonlinear function of the model parameters. All P values (Wald test) reported vs placebo.

The difference vs placebo was analyzed using Fisher exact test.

Change in Angioedema Quality of Life scores are controlled for baseline scores and are least square means.

This is a single P value <.001 for the analysis of covariance test, which shows the difference among the 4 groups.

Analysis of covariance post hoc pairwise comparison (Tukey-Kramer) vs placebo.

Patients who were considered to have responded (responders) to the therapy were defined as achieving an improvement greater than or equal to the minimal clinically important difference of –6 for total scores from days 0 through 182. The questionnaire consisted of 4 domains (functioning, fatigue and mood, fears and shame, and nutrition) and 17 questions that were taken together for a total score. Total raw scores were transformed to a linear scale of 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating lower impairment or higher health–related quality of life.20 Odds ratios represent times the odds (vs not) to achieve a responder definition compared with placebo.

Quality of Life

Patients experienced a significant improvement in quality of life total scores over 26 weeks in all 3 lanadelumab treatment groups compared with placebo (Table 4). A higher proportion of patients treated with lanadelumab (65.4% in the 150-mg every-4-week group, P = .047; 63.0% in the 300-mg every-4-week group, P = .07; and 80.8% in the 300-mg every-2-week group, P = .001) achieved the minimal clinically important difference in total quality of life score20 compared with placebo (36.8%). This corresponded to patients treated with lanadelumab having a significantly greater likelihood of achieving a minimal clinically important difference (odds ratios, 3.2 in the 150-mg every-4-week group, P = .03; 2.9 in the 300-mg every-4-week group, P = .04; and 7.2 in the 300-mg every-2-week group, P = .001) compared with placebo.

Adverse Events

The most commonly reported treatment-emergent adverse events (excluding hereditary angioedema attacks) in patients treated with lanadelumab during the entire treatment period were injection site pain (42.9%), viral upper respiratory tract infection (23.8%), headache (20.2%), injection site erythema (9.5%), injection site bruising (7.1%), and dizziness (6.0%; Table 5). Most treatment-emergent adverse events (98.5%) were mild to moderate in severity. The most commonly reported treatment-emergent adverse events in patients treated with lanadelumab that were considered related to treatment were injection site pain (41.7%), injection site erythema (9.5%), injection site bruising (6.0%), and headache (7.1%). There were no deaths or related serious treatment-emergent adverse events.

Table 5. Adverse Eventsa.

| Adverse Eventsb | No. (%) of Patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lanadelumab | Placebo (n = 41) | ||||

| Every 4 Weeks | 300 mg Every 2 Weeks (n = 27) | Total (n = 84) | |||

| 150 mg (n = 28) | 300 mg (n = 29) | ||||

| Any adverse event | 25 (89.3) | 25 (86.2) | 26 (96.3) | 76 (90.5) | 31 (75.6) |

| Injection site pain | 13 (46.4) | 9 (31.0) | 14 (51.9) | 36 (42.9) | 12 (29.3) |

| Viral upper respiratory tract infection | 3 (10.7) | 7 (24.1) | 10 (37.0) | 20 (23.8) | 11 (26.8) |

| Headache | 3 (10.7) | 5 (17.2) | 9 (33.3) | 17 (20.2) | 8 (19.5) |

| Injection site | |||||

| Erythema | 4 (14.3) | 2 (6.9) | 2 (7.4) | 8 (9.5) | 1 (2.4) |

| Bruising | 3 (10.7) | 2 (6.9) | 1 (3.7) | 6 (7.1) | 0 |

| Dizziness | 1 (3.6) | 3 (10.3) | 1 (3.7) | 5 (6.0) | 0 |

| Any treatment-related adverse eventc | 17 (60.7) | 14 (48.3) | 19 (70.4) | 50 (59.5) | 14 (34.1) |

| Injection site | |||||

| Pain | 12 (42.9) | 9 (31.0) | 14 (51.9) | 35 (41.7) | 11 (26.8) |

| Erythema | 4 (14.3) | 2 (6.9) | 2 (7.4) | 8 (9.5) | 1 (2.4) |

| Bruising | 2 (7.1) | 2 (6.9) | 1 (3.7) | 5 (6.0) | 0 |

| Headache | 1 (3.6) | 2 (6.9) | 3 (11.1) | 6 (7.1) | 1 (2.4) |

| Any serious adverse eventd | 0 | 3 (10.3) | 1 (3.7) | 4 (4.8) | 0 |

| Any related serious adverse event | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Any adverse event leading to discontinuation | 0 | 1 (3.4) | 0 | 1 (1.2) | 1 (2.4)e |

All patients received injections every 2 weeks, with those in the every-4-week groups receiving placebo in between active treatments.

Treatment-emergent adverse events that were reported at the Preferred Term level in 5% or more of patients in the total lanadelumab-treated group and excludes hereditary angioedema attack–reported events. Adverse events were collected over the entire treatment period and were assigned to the treatment group without regard to the type of injection (ie, placebo or active drug in the 150-mg every-4-week and 300-mg every-4-week groups).

Adverse events that were judged by the investigator to be related to the use of the investigational product.

See eTable 13 in Supplement 2 for details on serious adverse events.

One patient withdrew due to a hereditary angioedema attack and is not included. See eTable 12 in Supplement 2 for details on adverse events leading to discontinuation.

Two patients who received placebo withdrew from the study due to treatment-emergent adverse events of tension headache and hereditary angioedema attack, which were of moderate severity. One patient in the lanadelumab 300-mg every-4-week group with metabolic syndrome, fatty liver, and multiple concomitant suspect medications withdrew due to isolated, asymptomatic, and transient elevation of alanine transaminase (140 U/L) and aspartate transaminase (143 U/L) classified as related and severe on day 139 (see eTable 12 in Supplement 2; to convert aspartate and alanine transaminase from U/L to μkat/L, multiply by 0.0167).

Clinical Laboratory Findings

During the screening and treatment periods, all patients (100%) who received placebo and 83 of 84 patients (98.8%) in the pooled lanadelumab treatment groups had values 1.5 times or less than the upper limit of normal for activated partial thromboplastin time. The value increased to more than 1.5 times the upper limit of normal for 1 patient (1.2%) who received 300-mg every 2 weeks (eTables 14, 15, and 16 in Supplement 2).

Hypersensitivity Reactions

One patient in the 300-mg every-2-week group reported 2 hypersensitivity reactions with symptoms of mouth tingling and pruritus, which were of mild and moderate intensity, transient, and recovered without need for treatment or future premedication. The patient continued into the open-label extension. No laboratory abnormalities or presence of antidrug antibodies were observed in this patient to date.

Antidrug Antibodies

Ten of 84 patients (11.9%) in the lanadelumab group and 2 of 41 patients (4.9%) in the placebo group tested positive for low-titer (range, 20-1280) treatment-emergent antidrug antibodies, which were transient in 2 of 10 patients treated with lanadelumab and 1 of 2 patients treated with placebo. Low preexisting antibody titers were observed in 3 patients in the lanadelumab group and 1 in the placebo group with antidrug antibody positivity. Neutralizing antibodies were detected near the end of the treatment period in 2 patients who received 150-mg of lanadelumab every 4 weeks; 1 was transient (see eTables 17 and 18 in Supplement 2).

Discussion

In this study, all 3 lanadelumab treatment regimens produced statistically significant reductions in the mean hereditary angioedema attack rate compared with placebo for the number of attacks from days 0 to 182, the number of attacks requiring acute treatment, and the number of moderate or severe attacks, as well as the number of attacks from days 14 through 182.

In addition to a reduction in the overall hereditary angioedema attack rate, reductions in the number of attacks requiring acute treatment or that were moderate or severe reflects the full treatment effect of lanadelumab in reducing the burden of individual breakthrough hereditary angioedema attacks. The number of attacks and the change in attack rate with lanadelumab treatment vs placebo from days 14 through 182 was similar to those from days 0 through 182, indicating an early onset of the treatment effect of lanadelumab.

Even with 56% of patients receiving prior long-term prophylaxis, 52% experiencing 3 or more hereditary angioedema attacks during the run-in period, and 64.8% with a history of laryngeal attacks, a total of 38.1% of patients treated with lanadelumab were attack free over the entire treatment period. Furthermore, estimates of treatment effect for the primary and secondary efficacy analyses were assessed by including all hereditary angioedema attacks after the first dose of the study drug, despite time to steady state concentrations for lanadelumab being approximately 70 days.14 In a post hoc analysis looking only at the effect of lanadelumab during the steady-state period, the reduction in attack rates raises the possibility that there could be further improvement in controlling hereditary angioedema once steady-state concentrations are achieved.

A significant improvement in patient-reported health–related quality of life was demonstrated in the study. The extent of improvement in quality of life total scores with lanadelumab compared with placebo was similar to that seen with omalizumab compared with placebo for the treatment of chronic spontaneous urticaria in patients with recurrent angioedema21 and was greater than that seen with subcutaneous C1 inhibitor with recombinant hyaluronidase for prophylaxis,22 although treatment duration differed in these trials.

The majority (93.3%) of treatment-emergent adverse events related to lanadelumab were associated with the injection site. The higher incidence of related treatment-emergent adverse events among patients treated with lanadelumab was predominantly due to injection site pain (reported by 41.7% of lanadelumab-treated patients vs 26.8% who received placebo), contrasting with previous findings in which the incidence of injection site pain was comparable between patients treated with lanadelumab and placebo.14 Overall, the rates of injection site pain may have been associated with the requirement for the study drug to be administered as 2 separate 1.0-mL injections in the upper arm to maintain blinding. Additional clarity may be gained from the ongoing open-label extension, during which patients are able to self-administer a single injection at a site of their choosing (abdomen, thigh, or upper arm).17

Antidrug antibodies of low titer developed in 11.9% of patients treated with lanadelumab and 4.9% of patients treated with placebo. As a monoclonal antibody, lanadelumab is considered to have a lower risk of off-target effects due to its high selectivity and specificity; however, the possibility of an immune response to this fully human monoclonal antibody should be considered. Two patients treated with lanadelumab 150 mg every 4 weeks developed antibodies that showed neutralizing properties in vitro. There are other potential antigenic sites on lanadelumab and not all would interfere with the binding of plasma kallikrein. Thus, it would be possible that nonneutralizing antidrug antibodies are directed to epitopes on lanadelumab other than those engaged in binding plasma kallikrein. The identification of antidrug antibodies to lanadelumab in patients treated with placebo is likely attributed to the high sensitivity of the assay and the potential for false-positive results.

This study had an observation period of 26 weeks of treatment; therefore, it was not possible to assess the adverse events and preventive effects of continuous prophylaxis with long-term plasma kallikrein inhibition. Data from the ongoing open-label extension17 will provide additional insights into these areas. Of note, in patients with severe congenital deficiency of prekallikrein (Fletcher factor deficiency), the main laboratory finding is a prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time.23 In the current study, all but 1 patient treated with lanadelumab maintained an activated partial thromboplastin time of less than 1.5 times the upper limit of normal throughout the treatment period.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, there were relatively few patients in each treatment group, which led to imbalances in some baseline demographic and clinical characteristics.

Second, this study was limited to 26 weeks. Although most patients would likely continue therapy with lanadelumab over a long period, conclusions on long-term safety and efficacy cannot be made.

Third, the reported number of attacks in the 12 months before screening were based on patient historical recall, and the attacks were not investigator confirmed. Thus, these data should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions

Among patients with hereditary angioedema type I or II, treatment with subcutaneous lanadelumab for 26 weeks significantly reduced the number of attacks compared with placebo, supporting the use of lanadelumab as a prophylactic therapy for hereditary angioedema. Further research is needed to determine long-term safety and efficacy.

Trial protocol

eMethods 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

eMethods 2. Criteria for Investigator-Confirmed Hereditary Angioedema Attacks

eMethods 3. Treatment Period Dosing Schedule

eMethods 4. Assessment of Attacks and Adverse Events

eMethods 5. Statistical Analysis

eFigure 1. Study Design

eFigure 2. Mean HAE Attack Rates by Study Month and Treatment Group

eTable 1. HELP Study Administrative Structure

eTable 2. Duration of Treatment for Patients Who Discontinued

eTable 3. Number of Patients by Duration of Run-in Period

eTable 4. Number of Patients by Run-in Attack Rate Category

eTable 5. Primary Attack Location During Run-in and Treatment Period

eTable 6. Duration of Attacks

eTable 7. Summary of On-Demand Treatment for Attacks and the Use of Supportive Therapies for Symptoms

eTable 8. Efficacy Outcomes by Subgroup

eTable 9. Tipping Point Analysis

eTable 10. Number of Patients by Geographical Region

eTable 11. Mean Number of Attacks Days 0-182, Adjusted by Geographical Region

eTable 12. Listing of Patients Who Discontinued During Treatment Due to Adverse Events

eTable 13. Summary of Serious Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events

eTable 14. Summary of Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time

eTable 15. Shift Table of Highest Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time

eTable 16. Clinically Significant Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time Results

eTable 17. Summary of Immunogenicity Response

eTable 18. Summary of Positive Immunogenicity Results

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Zuraw BL, Christiansen SC. HAE pathophysiology and underlying mechanisms. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51(2):216-229. doi: 10.1007/s12016-016-8561-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zuraw BL. Hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(10):1027-1036. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0803977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernstein JA. HAE update: epidemiology and burden of disease. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2013;34(1):3-6. doi: 10.2500/aap.2013.34.3623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Longhurst H, Bygum A. The humanistic, societal, and pharmaco-economic burden of angioedema. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51(2):230-239. doi: 10.1007/s12016-016-8575-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bygum A, Aygören-Pürsün E, Beusterien K, et al. Burden of illness in hereditary angioedema: a conceptual model. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(6):706-710. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craig T, Aygören-Pürsün E, Bork K, et al. WAO guideline for the management of hereditary angioedema. World Allergy Organ J. 2012;5(12):182-199. doi: 10.1097/WOX.0b013e318279affa [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riedl MA. Critical appraisal of androgen use in hereditary angioedema: a systematic review. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;114(4):281-288.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Longhurst H, Cicardi M, Craig T, et al. ; COMPACT Investigators . COMPACT Investigators. Prevention of hereditary angioedema attacks with a subcutaneous C1 inhibitor. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(12):1131-1140. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1613627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zuraw BL, Busse PJ, White M, et al. Nanofiltered C1 inhibitor concentrate for treatment of hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(6):513-522. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernstein JA, Manning ME, Li H, et al. Escalating doses of C1 esterase inhibitor (CINRYZE) for prophylaxis in patients with hereditary angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(1):77-84. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2013.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wintenberger C, Boccon-Gibod I, Launay D, et al. Tranexamic acid as maintenance treatment for non-histaminergic angioedema: analysis of efficacy and safety in 37 patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;178(1):112-117. doi: 10.1111/cei.12379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chyung Y, Vince B, Iarrobino R, et al. A phase 1 study investigating DX-2930 in healthy subjects. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;113(4):460-6.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kenniston JA, Faucette RR, Martik D, et al. Inhibition of plasma kallikrein by a highly specific active site blocking antibody. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(34):23596-23608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.569061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banerji A, Busse P, Shennak M, et al. Inhibiting plasma kallikrein for hereditary angioedema prophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(8):717-728. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1605767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Longhurst HJ. Kallikrein inhibition for hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(8):788-789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1611929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riedl MA, Bernstein JA, Craig T, et al. An open-label study to evaluate the long-term safety and efficacy of lanadelumab for prevention of attacks in hereditary angioedema: design of the HELP study extension. Clin Transl Allergy. 2017;7:36. doi: 10.1186/s13601-017-0172-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (DMID) adult toxicity table. November 2007. Draft. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/sites/default/files/dmidadulttox.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2017.

- 19.Weller K, Groffik A, Magerl M, et al. Development and construct validation of the angioedema quality of life questionnaire. Allergy. 2012;67(10):1289-1298. doi: 10.1111/all.12007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weller K, Magerl M, Peveling-Oberhag A, Martus P, Staubach P, Maurer M. The Angioedema Quality of Life Questionnaire (AE-QoL)—assessment of sensitivity to change and minimal clinically important difference. Allergy. 2016;71(8):1203-1209. doi: 10.1111/all.12900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staubach P, Metz M, Chapman-Rothe N, et al. Omalizumab rapidly improves angioedema-related quality of life in adult patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: X-ACT study data. Allergy. 2018;73(3):576-584. doi: 10.1111/all.13339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weller K, Maurer M, Fridman M, Supina D, Schranz J, Magerl M. Health-related quality of life with hereditary angioedema following prophylaxis with subcutaneous C1-inhibitor with recombinant hyaluronidase. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2017;38(2):143-151. doi: 10.2500/aap.2017.38.4025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girolami A, Scarparo P, Candeo N, Lombardi AM. Congenital prekallikrein deficiency. Expert Rev Hematol. 2010;3(6):685-695. doi: 10.1586/ehm.10.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol

eMethods 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

eMethods 2. Criteria for Investigator-Confirmed Hereditary Angioedema Attacks

eMethods 3. Treatment Period Dosing Schedule

eMethods 4. Assessment of Attacks and Adverse Events

eMethods 5. Statistical Analysis

eFigure 1. Study Design

eFigure 2. Mean HAE Attack Rates by Study Month and Treatment Group

eTable 1. HELP Study Administrative Structure

eTable 2. Duration of Treatment for Patients Who Discontinued

eTable 3. Number of Patients by Duration of Run-in Period

eTable 4. Number of Patients by Run-in Attack Rate Category

eTable 5. Primary Attack Location During Run-in and Treatment Period

eTable 6. Duration of Attacks

eTable 7. Summary of On-Demand Treatment for Attacks and the Use of Supportive Therapies for Symptoms

eTable 8. Efficacy Outcomes by Subgroup

eTable 9. Tipping Point Analysis

eTable 10. Number of Patients by Geographical Region

eTable 11. Mean Number of Attacks Days 0-182, Adjusted by Geographical Region

eTable 12. Listing of Patients Who Discontinued During Treatment Due to Adverse Events

eTable 13. Summary of Serious Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events

eTable 14. Summary of Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time

eTable 15. Shift Table of Highest Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time

eTable 16. Clinically Significant Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time Results

eTable 17. Summary of Immunogenicity Response

eTable 18. Summary of Positive Immunogenicity Results

Data Sharing Statement