Key Points

Question

What is the association between an organic food–based diet (ie, a diet less likely to contain pesticide residues) and cancer risk?

Findings

In a population-based cohort study of 68 946 French adults, a significant reduction in the risk of cancer was observed among high consumers of organic food.

Meaning

A higher frequency of organic food consumption was associated with a reduced risk of cancer; if the findings are confirmed, research investigating the underlying factors involved with this association is needed to implement adapted and targeted public health measures for cancer prevention.

Abstract

Importance

Although organic foods are less likely to contain pesticide residues than conventional foods, few studies have examined the association of organic food consumption with cancer risk.

Objective

To prospectively investigate the association between organic food consumption and the risk of cancer in a large cohort of French adults.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this population-based prospective cohort study among French adult volunteers, data were included from participants with available information on organic food consumption frequency and dietary intake. For 16 products, participants reported their consumption frequency of labeled organic foods (never, occasionally, or most of the time). An organic food score was then computed (range, 0-32 points). The follow-up dates were May 10, 2009, to November 30, 2016.

Main Outcomes and Measures

This study estimated the risk of cancer in association with the organic food score (modeled as quartiles) using Cox proportional hazards regression models adjusted for potential cancer risk factors.

Results

Among 68 946 participants (78.0% female; mean [SD] age at baseline, 44.2 [14.5] years), 1340 first incident cancer cases were identified during follow-up, with the most prevalent being 459 breast cancers, 180 prostate cancers, 135 skin cancers, 99 colorectal cancers, 47 non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and 15 other lymphomas. High organic food scores were inversely associated with the overall risk of cancer (hazard ratio for quartile 4 vs quartile 1, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.63-0.88; P for trend = .001; absolute risk reduction, 0.6%; hazard ratio for a 5-point increase, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.88-0.96).

Conclusions and Relevance

A higher frequency of organic food consumption was associated with a reduced risk of cancer. If these findings are confirmed, further research is necessary to determine the underlying factors involved in this association.

This population-based cohort study investigates the association between organic food consumption and the risk of cancer in a large cohort of French adults.

Introduction

Worldwide, the number of new cases of cancer was estimated in 2012 at more than 14 million,1,2 and cancer remains one of the leading causes of mortality in France. Among the environmental risk factors for cancer, there are concerns about exposure to different classes of pesticides, notably through occupational exposure.3 A recent review4 concluded that the role of pesticides for the risk of cancer could not be doubted given the growing body of evidence linking cancer development to pesticide exposure. While dose responses of such molecules or possible cocktail effects are not well known, an increase in toxic effects has been suggested even at low concentrations of pesticide mixtures.5

Meanwhile, the organic food market continues to grow rapidly in European countries,6 propelled by environmental and health concerns.7,8,9,10 Organic food standards do not allow the use of synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and genetically modified organisms and restrict the use of veterinary medications.11 As a result, organic products are less likely to contain pesticide residues than conventional foods.12,13 According to a 2018 European Food Safety Authority13 report, 44% of conventionally produced food samples contained 1 or more quantifiable residues, while 6.5% of organic samples contained measurable pesticide residues. In line with this report, diets mainly consisting of organic foods were linked to lower urinary pesticide levels compared with “conventional diets” in an observational study14 of adults carried out in the United States (the median dialkyphosphate concentration among low organic food consumers was 163 nmol/g of creatinine, while among regular organic food consumers it was reduced to 106 nmol/g of creatinine). This finding was more marked in a clinical study15 from Australia and New Zealand (a 90% reduction in total dialkyphosphate urinary biomarkers was observed after an organic diet intervention) conducted in adults.

Because of their lower exposure to pesticide residues, it can be hypothesized that high organic food consumers may have a lower risk of developing cancer. Furthermore, natural pesticides allowed in organic farming in the European Union16 exhibit much lower toxic effects than the synthetic pesticides used in conventional farming.17 Nevertheless, only 1 study18 to date has focused on the association between frequency of organic food consumption and cancer risk, reporting a lower risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) only. However, consumption of organic food was assessed using only a basic question. Multiple studies19,20,21,22,23,24 have reported a strong positive association between regular organic food consumption and healthy dietary habits and other lifestyles. Hence, these factors should be carefully accounted for in etiological studies in this research field. In the present population-based cohort study among French adult volunteers, we sought to prospectively examine the association between consumption frequency of organic foods, assessed through a score evaluating the consumption frequency of organic food categories, and cancer risk in the ongoing, large-scale French NutriNet-Santé cohort. The follow-up dates of the study were May 10, 2009, to November 30, 2016.

Methods

Study Population

The NutriNet-Santé study is a web-based prospective cohort in France aiming to study the associations between nutrition and health, as well as the determinants of dietary behaviors and nutritional status. This cohort was launched in 2009 and has been previously described in detail.25 Volunteers with access to the internet are recruited from the general population and complete online self-administrated questionnaires using a dedicated website.

The NutriNet-Santé study is conducted in accord with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.26 It was approved by the institutional review board of the French Institute for Health and Medical Research and the Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés. The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03335644). Electronic informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Data Collection

The baseline questionnaires investigating sociodemographics and lifestyles, health status, physical activity, anthropometrics, and diet were pilot tested and then compared against traditional assessment methods or objectively validated.27,28,29,30,31,32 Two months after enrollment, volunteers were asked to provide information on their consumption frequency of 16 labeled organic products (fruits; vegetables; soy-based products; dairy products; meat and fish; eggs; grains and legumes; bread and cereals; flour; vegetable oils and condiments; ready-to-eat meals; coffee, tea, and herbal tea; wine; biscuits, chocolate, sugar, and marmalade; other foods; and dietary supplements). Consumption frequencies of organic foods were reported using the following 8 modalities: (1) most of the time, (2) occasionally, (3) never (“too expensive”), (4) never (“product not available”), (5) never (“I’m not interested in organic products”), (6) never (“I avoid such products”), (7) never (“for no specific reason”), and (8) “I don’t know.” For each product, we allocated 2 points for “most of the time” and 1 point for “occasionally” (and 0 otherwise). The 16 components were summed to provide an organic food score (range, 0-32 points).

At study inclusion, dietary intake was assessed using three 24-hour records, randomly allocated over a 2-week period, including 2 weekdays and 1 weekend day, with a validated method.30 Participants reported all foods and beverages consumed at each eating occasion. Portion sizes were estimated using photographs from a previously validated picture booklet33 or directly entered as grams, volumes, or purchased units. Alcohol intake was calculated using either the 24-hour records or a frequency questionnaire for those identified as abstainers in the three 24-hour record days. Similarly, the weekly consumption of seafood was assessed by a specific frequency question. Daily mean food consumption was calculated from the three 24-hour records completed at inception and weighted for the type of day (weekday or weekend day). Ultraprocessed food consumption was assessed using the NOVA classification.34,35

Nutrients intakes were derived from individuals’ food intakes assessed via the 24-hour records and were calculated using the NutriNet-Santé food composition table.36 Underreporters were identified and excluded using the method by Black.37

Diet quality was assessed using a modified version of the validated Programme National Nutrition Santé Guideline Score without the physical activity component (mPNNS-GS), reflecting adherence to the official French nutritional guidelines.38 Components, cutoffs, and scoring are summarized in eTable 1 in the Supplement.

At baseline, data on age, sex, occupational status, educational level, marital status, monthly income per household unit, number of children, and smoking status were collected. Monthly income per household unit was calculated by dividing the household’s total monthly income by the number of consumption units.39 The following categories of monthly income per household unit were used: less than €1200 (less than US $1377.46), €1200 to €1800 (US $1377.46 to US $2066.18), greater than €1800 to €2700 (greater than US $2066.18 to US $3099.28), and greater than €2700 (greater than US $3099.28). Physical activity was assessed by the International Physical Activity Questionnaire.40

Anthropometric questionnaires provided information on weight and height. The use of dietary supplements (yes or no) and sun exposure were assessed using specific questionnaires. For sun exposure, the question was formulated as follows: “During adulthood, have you been regularly exposing yourself to the sun?” (yes or no).

Case Ascertainment

Participants self-declared health events through a yearly health status questionnaire or using an interface on the study website allowing the entering of health events at any time. For each reported cancer case, individuals were asked by a study physician (P.G. and other nonauthors) to provide their medical records (diagnoses, hospitalizations, etc). The study physicians contacted the participants’ treating physician or the respective hospitals to collect additional information if necessary. All medical information was collegially reviewed by an independent medical expert committee for the validation of major health events. Overall, medical records were obtained for more than 90% of self-reported cancer cases. Linkage of our data (decree authorization in the Council of State No. 2013-175) to medicoadministrative registers of the national health insurance system (Système National d’Information Inter-Régimes de l’Assurance Maladie [SNIIRAM] databases) allowed complete reporting of health events. Mortality data were also used from the French Centre for Epidemiology Medical Causes of Death database (CépiDC). Cancer cases were classified using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification.41 In this study, all first primary cancers diagnosed between study inclusion and November 30, 2016, were considered cases except for basal cell skin carcinoma, which was not considered cancer.

Statistical Analysis

For the present study, we used data from volunteers who were enrolled before December 2016 who completed the organic food questionnaire (n = 95 123) and did not have prevalent cancer (except for basal cell skin carcinoma) (n = 89 711), with a final population of 68 946 adults who had available data for the computation of the mPNNS-GS and follow-up data. The studied sample was compared with participants who were in the eligible population but who were excluded because of missing data (eTable 2 in the Supplement). To date, the dropout rate in the NutriNet-Santé cohort is 6.7%.

Baseline characteristics are presented by quartile (Q) of the organic food score. Cox proportional hazards regression models with age as time scale were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs, reflecting the association between the organic food score (as a continuous variable, while modeling the HR associated with each 5-point increase, and as quartiles, with the first quartile as reference) and the incidence of overall cancer. A 5-point increment corresponded to half of the interquartile range. Tests for linear trend were performed using quartiles of the organic food score as an ordinal variable. Full details about cancer risk modeling are provided in the eAppendix in the Supplement, with additional information included in eTables 3 through 6 in the Supplement.

All statistical tests were 2 sided, and P < .05 was considered statistically significant. A statistical software program (SAS, version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc) was used for analyses.

Results

The mean (SD) follow-up time in our study sample was 4.56 (2.08) years; 78.0% of 68 946 participants were female, and the mean (SD) age at baseline was 44.2 (14.5) years. During follow-up, 1340 first incident cancer cases were identified, with the most prevalent being 459 breast cancers (34.3%), 180 prostate cancers (13.4%), 135 skin cancers (melanoma and spinocellular carcinoma) (10.1%), 99 colorectal cancers (7.4%), 47 NHLs (3.5%), and 15 other lymphomas (1.1%).

Baseline Characteristics of the Sample

Higher organic food scores were positively associated with female sex, high occupational status or monthly income per household unit, postsecondary graduate educational level, physical activity, and former smoking status (Table 1). Higher organic food scores were also associated with a higher mPNNS-GS. Dietary characteristics by organic food score quartiles are summarized in eTable 7 in the Supplement. Higher organic food scores were associated with a healthier diet rich in fiber, vegetable proteins, and micronutrients. Higher organic food scores were also associated with higher intake of fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes and with lower intake of processed meat, other meat, poultry, and milk.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics According to Quartiles of the Organic Food Score, NutriNet-Santé Cohort, France, 2009 to 2016.

| Characteristic | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic food score, mean (SD), range, 0-32 points | 0.72 (0.82) | 4.95 (1.41) | 10.36 (1.69) | 19.36 (4.28) | <.001 |

| Participants, No. | 16 831 | 17 644 | 17 240 | 17 231 | NA |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 42.99 (15.24) | 43.31 (14.78) | 44.72 (14.30) | 45.89 (13.37) | <.001 |

| Female, % | 74.2 | 78.2 | 78.7 | 80.9 | <.001 |

| Month of inclusion, mean (SD)b | 6.08 (2.56) | 6.11 (2.57) | 6.10 (2.74) | 5.99 (2.93) | .002 |

| Occupational status, % | |||||

| Unemployed | 5.9 | 5.7 | 5.6 | 6.3 | <.001 |

| Student | 9.5 | 9.3 | 7.3 | 4.6 | |

| Self-employed, farmer | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 2.5 | |

| Employee, manual worker | 24.4 | 20.6 | 17.4 | 14.9 | |

| Intermediate professions | 16.3 | 17.6 | 17.8 | 18.8 | |

| Managerial staff, intellectual profession | 17.8 | 21.6 | 25.9 | 29.1 | |

| Retired | 19.0 | 17.9 | 18.9 | 17.8 | |

| Never employed | 5.5 | 5.6 | 5.4 | 6.1 | |

| Educational level, % | |||||

| Unidentified | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.8 | <.001 |

| <High school diploma | 22.8 | 19.4 | 16.4 | 14.4 | |

| High school diploma | 19.7 | 17.4 | 15.7 | 13.7 | |

| Postsecondary graduate | 56.9 | 62.6 | 67.4 | 71.1 | |

| Marital status, % | |||||

| Cohabiting | 79.6 | 80.6 | 81.8 | 85.3 | <.001 |

| Monthly income per household unit, €, %c | |||||

| <1200 | 20.7 | 17.0 | 14.0 | 13.2 | <.001 |

| 1200 to 1800 | 26.9 | 25.3 | 22.9 | 23.5 | |

| >1800 to 2700 | 21.2 | 23.3 | 24.7 | 25.6 | |

| >2700 | 18.8 | 22.4 | 27.6 | 28.2 | |

| Unwilling to answer | 12.4 | 12.0 | 10.8 | 9.5 | |

| Physical activity, %d | |||||

| Low, <30 min of brisk walking per day or equivalent | 24.0 | 20.8 | 19.0 | 17.2 | .03 |

| Moderate, 30 to <60 min of brisk walking per day or equivalent | 33.7 | 37.3 | 38.8 | 40.6 | |

| High, ≥60 min of brisk walking per day or equivalent | 26.8 | 27.3 | 29.5 | 31.3 | |

| Missing data | 15.5 | 14.5 | 12.7 | 11.0 | |

| Smoking status, % | |||||

| Never smoker | 52.0 | 51.9 | 50.2 | 49.4 | <.001 |

| Former smoker | 31.6 | 31.9 | 34.5 | 36.8 | |

| Current smoker | 16.4 | 16.2 | 15.3 | 13.8 | |

| Alcohol intake, mean (SD), g/d | 8.34 (13.84) | 8.18 (13.11) | 8.17 (12.19) | 7.54 (11.30) | |

| Family history of cancer, % | 33.8 | 34.5 | 36.8 | 38.6 | <.001 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 24.46 (4.92) | 23.92 (4.63) | 23.64 (4.32) | 22.92 (3.89) | <.001 |

| Height, mean (SD), cm | 166.91 (8.27) | 166.58 (8.05) | 166.54 (8.11) | 166.40 (7.98) | <.001 |

| Energy intake, mean (SD), kcal/de | 1881.71 (493.19) | 1855.10 (469.03) | 1848.42 (474.71) | 1841.24 (464.11) | <.001 |

| mPNNS-GS, mean (SD) | 7.41 (1.72) | 7.70 (1.71) | 7.95 (1.71) | 8.19 (1.69) | <.001 |

| Fiber intake, mean (SD), g/d | 17.88 (6.55) | 18.87 (6.84) | 20.05 (7.20) | 22.60 (8.31) | <.001 |

| Processed meat intake, mean (SD), g/d | 23.67 (29.40) | 21.15 (27.12) | 18.85 (24.92) | 15.12 (22.49) | <.001 |

| Red meat intake, mean (SD), g/d | 48.72 (44.51) | 44.59 (41.44) | 40.77 (40.67) | 31.44 (36.81) | <.001 |

| Parity, mean (SD)f | 1.26 (1.26) | 1.27 (1.23) | 1.34 (1.23) | 1.41 (1.21) | <.001 |

| Postmenopausal status, %f | 16.6 | 19.3 | 22.4 | 24.7 | <.001 |

| Use of hormonal treatment for menopause, %f | 4.0 | 4.6 | 5.0 | 4.9 | .01 |

| Use of oral contraception, %f | 24.7 | 23.2 | 19.1 | 14.0 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); mPNNS-GS, Programme National Nutrition Santé Guideline Score without the physical activity component; NA, not applicable; Q, quartile.

P value based on linear trend for continuous variables or Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test for categorical variables.

This category indicates the month of the year during which the particpant was included.

In 2018 US dollars, the monetary ranges are “less than $1377.46,” “$1377.46 to $2066.18,” “greater than $2066.18 to $3099.28,” and “greater than $3099.28.”

Physical activity levels assessed using the French short form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire self-administered online.

Energy intake without alcohol.

For women.

Organic Food Score in Relation to Cancer Risk

The association between the organic food score and the overall risk of cancer is summarized in Table 2. After adjustment for confounders (main model), high organic food scores were linearly and negatively associated with the overall risk of cancer (HR for Q4 vs Q1, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.63-0.88; P for trend = .001; absolute risk reduction, 0.6%; HR for a 5-point increase, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.88-0.96). Accounting for other additional dietary factors did not modify the findings. After removing early cases of cancers (eTable 5 in the Supplement), the overall association remained significant (HR for Q4 vs Q1, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.56-0.88; P for trend = .004).

Table 2. Multivariable Associations Between the Organic Food Score (Modeled as a Continuous Variable and as Quartiles) and Overall Cancer Risk, NutriNet-Santé Cohort, France, 2009 to 2016.

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P Value for Trenda | HR (95% CI) for a 5-Point Increase | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | ||||

| Cases/noncases | 360/16471 | 358/17286 | 353/16887 | 269/16962 | NA | NA | NA |

| Model 1b | 1 [Reference] | 0.93 (0.80-1.07) | 0.90 (0.78-1.04) | 0.70 (0.60-0.83) | <.001 | 0.91 (0.87-0.94) | <.001 |

| Model 2c | 1 [Reference] | 0.94 (0.81-1.09) | 0.92 (0.79-1.07) | 0.75 (0.63-0.88) | .001 | 0.92 (0.88-0.96) | <.001 |

| Model 3d | 1 [Reference] | 0.94 (0.81-1.09) | 0.93 (0.80-1.08) | 0.76 (0.64- 0.90) | .003 | 0.93 (0.89-0.97) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; mPNNS-GS, Programme National Nutrition Santé Guideline Score without the physical activity component; NA, not applicable; Q, quartile.

P value for linear trend obtained from the quartile classification by modeling organic food score quartiles as an ordinal variable.

Model 1 is adjusted for age (time scale) and sex.

Model 2 is adjusted for age (time scale) and sex, month of inclusion, occupational status, educational level, marital status, monthly income per household unit, physical activity, smoking status, alcohol intake, family history of cancer, body mass index, height, energy intake, mPNNS-GS, fiber intake, processed meat intake and red meat intake, and (for women) parity, postmenopausal status, use of hormonal treatment for menopause, and use of oral contraception.

Model 3 is model 2 plus further adjustments for ultraprocessed food consumption, fruit and vegetable consumption, and dietary patterns extracted by principal component analysis.

Combining both a high-quality diet and a high frequency of organic food consumption did not seem to be associated with a reduced risk of overall cancer compared with a low-quality diet and a low frequency of organic food consumption. Negative associations were found between the risk of cancer and combining both a low- to medium-quality diet and a high frequency of organic food consumption (eTable 6 in the Supplement).

Population attributable risks (PAR) were calculated42 from multivariable-adjusted HRs (main model) in relation to the organic food score and a family history of cancer to identify how much of the risk was specifically attributable to the organic food score. Herein, PAR represents the proportion of cancer cases that can be attributed to any risk factor studied. By comparison, the number of avoided cancers (all types of cancer) owing to a high organic food consumption frequency was slightly lower than the estimated number of cases owing to a family history of cancer (% PAR high organic food score of −6.78 vs % PAR family history of cancer of 8.93) under the causality assumption.

Associations by cancer site are summarized in Table 3. Our findings revealed a negative association between high organic food scores and postmenopausal breast cancer, NHL, and all lymphomas. No associations were observed with other cancer sites.

Table 3. Multivariable Associations Between the Organic Food Score (Modeled as Quartiles) and Cancer Risk by Site, NutriNet-Santé Cohort, France, 2009 to 2016a.

| Variable | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer, No. | 106 | 115 | 130 | 108 | NA |

| HR (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 0.89 (0.68-1.16) | 0.93 (0.71-1.20) | 0.77 (0.58-1.01) | .10 |

| Premenopausal breast cancer, No. | 52 | 59 | 66 | 50 | NA |

| HR (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 1.01 (0.69-1.47) | 1.13 (0.78-1.64) | 0.89 (0.59-1.35) | .76 |

| Postmenopausal breast cancer, No. | 69 | 55 | 58 | 50 | NA |

| HR (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 0.76 (0.53-1.08) | 0.75 (0.53-1.07) | 0.66 (0.45-0.96) | .03 |

| Prostate cancer, No. | 60 | 47 | 45 | 28 | NA |

| HR (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 0.96 (0.66-1.41) | 1.12 (0.75-1.66) | 1.00 (0.63-1.60) | .78 |

| Colorectal cancer, No. | 27 | 21 | 27 | 24 | NA |

| HR (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 0.77 (0.43-1.36) | 0.98 (0.57-1.69) | 0.87 (0.48-1.57) | .84 |

| Skin cancer, No. | 37 | 35 | 32 | 31 | NA |

| HR (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 0.80 (0.50-1.27) | 0.69 (0.43-1.12) | 0.63 (0.38-1.05) | .06 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, No. | 15 | 14 | 16 | 2 | NA |

| HR (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 0.98 (0.47-2.06) | 1.19 (0.57-2.48) | 0.14 (0.03-0.66) | .049 |

| All lymphomas, No. | 23 | 16 | 18 | 5 | NA |

| HR (95% CI) | 1 [Reference] | 0.72 (0.38-1.38) | 0.87 (0.46-1.65) | 0.24 (0.09-0.66) | .02 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; mPNNS-GS, Programme National Nutrition Santé Guideline Score without the physical activity component; NA, not applicable; Q, quartile.

Model is adjusted for age (time scale) and sex, month of inclusion, occupational status, educational level, marital status, monthly income per household unit, physical activity, smoking status, alcohol intake, family history of cancer, body mass index, height, energy intake, mPNNS-GS, fiber intake, processed meat intake and red meat intake, and (for women) parity, postmenopausal status, use of hormonal treatment for menopause, and use of oral contraception.

P value for linear trend obtained from the quartile classification by modeling organic food score quartiles as an ordinal variable.

Sensitivity Analysis

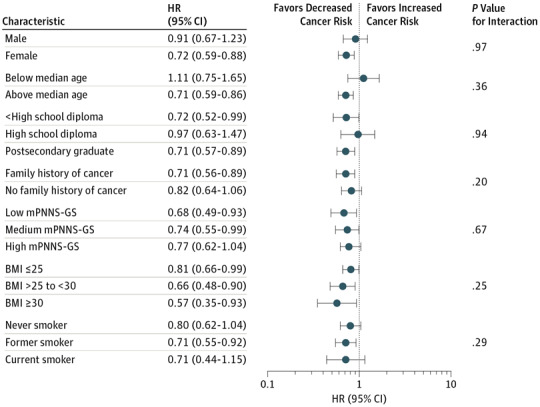

When applying a simplified, plant-derived organic food score, our main findings were not substantially changed except for postmenopausal breast cancer, for which the association with the organic food score did not remain significant (Table 4). When stratifying by various factors, significant associations were detected in women, older individuals, those with lower and higher educational levels, individuals with a family history of cancer, those with low to medium overall nutritional quality, all body mass index strata, and former smokers (Figure).

Table 4. Multivariable Associations Between a Simplified Organic Food Score (Modeled as a Continuous Variable and as Quartiles) and Overall Cancer Risk and Cancer Risk by Site, Sensitivity Analyses, NutriNet-Santé Cohort, France, 2009 to 2016a.

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P Value for Trendb | HR (95% CI) for a 5-Point Increase | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | ||||

| Overall cancer | 1 [Reference] | 0.94 (0.81-1.09) | 0.95 (0.83-1.09) | 0.75 (0.63-0.89) | .005 | 0.92 (0.88-0.96) | <.001 |

| Breast cancer | 1 [Reference] | 1.06 (0.81-1.39) | 1.01 (0.79-1.30) | 0.88 (0.66-1.16) | .38 | 0.95 (0.88-1.01) | .11 |

| Premenopausal breast cancer | 1 [Reference] | 1.10 (0.75-1.60) | 1.14 (0.80-1.61) | 1.01 (0.67-1.52) | .85 | 0.99 (0.99-1.09) | .86 |

| Postmenopausal breast cancer | 1 [Reference] | 1.03 (0.73-1.45) | 0.89 (0.60-1.33) | 0.79 (0.53-1.18) | .18 | 0.91 (0.83-1.01) | .07 |

| Prostate cancer | 1 [Reference] | 1.14 (0.77-1.68) | 1.34 (0.92-1.95) | 1.03 (0.61-1.73) | .39 | 1.02 (0.91-1.15) | .68 |

| Skin cancer | 1 [Reference] | 0.85 (0.54-1.35) | 0.53 (0.33-0.86) | 0.79 (0.49-1.28) | .11 | 0.89 (0.78-1.01) | .06 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 1 [Reference] | 0.80 (0.35-1.81) | 1.21 (0.61-2.43) | 0.27 (0.07-0.96) | .23 | 0.75 (0.60-0.93) | .009 |

| All lymphomas | 1 [Reference] | 0.56 (0.27-1.17) | 0.97 (0.54-1.74) | 0.23 (0.08-0.69) | .05 | 0.75 (0.60-0.93) | .03 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; mPNNS-GS, Programme National Nutrition Santé Guideline Score without the physical activity component; Q, quartile.

The simplified organic food score comprises the following plant-derived products that are the main determinants of pesticide exposure: fruits, vegetables, soy-based products, grains and legumes, bread and cereals, and flour. Model (main model) is adjusted for age (time scale) and sex, month of inclusion, occupational status, educational level, marital status, monthly income per household unit, physical activity, smoking status, alcohol intake, family history of cancer, body mass index, height, energy intake, mPNNS-GS, fiber intake, processed meat intake and red meat intake, and (for women) parity, postmenopausal status, use of hormonal treatment for menopause, and use of oral contraception.

P value for linear trend obtained from the quartile classification by modeling organic food score quartiles as an ordinal variable.

Figure. Association Between Quartiles of the Organic Food Score (Quartile 4 vs Quartile 1) and Overall Cancer Risk Stratified by Different Factors, NutriNet-Santé Cohort, France, 2009 to 2016.

BMI indicates body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); HR, hazard ratio; and mPNNS-GS, Programme National Nutrition Santé Guideline Score without the physical activity component.

Discussion

In this large cohort of French adults, we observed that a higher organic food score, reflecting a higher frequency of organic food consumption, was associated with a decreased risk of developing NHL and postmenopausal breast cancer, while no association was detected for other types of cancer. Epidemiological research investigating the link between organic food consumption and cancer risk is scarce, and, to the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to evaluate frequency of organic food consumption associated with cancer risk using detailed information on exposure. Therefore, frequency of organic food consumption for various food groups was assessed, and our models were adjusted for multiple important confounding factors (sociodemographics, lifestyles, and dietary patterns). Control for dietary patterns is of high importance because the current state of research in nutritional epidemiology emphasizes the strong associations between Western and healthy dietary patterns and the development of certain types of cancers.43,44,45

Our results contrast somewhat with the findings from the Million Women Study18 cohort among middle-aged women in the United Kingdom. In that large prospective study carried out among 623 080 women, consumption of organic food was not associated with a reduction in overall cancer incidence, while a small increase in breast cancer incidence was observed among women who reported usually or always eating organic food compared with women who reported never eating organic food. Moreover, despite different populations and assessment methods, similar results in that study and in our study were obtained with respect to NHL (in the Million Women Study, there was a 21% lower risk among regular organic food consumers compared with nonconsumers).

One possible explanation for the negative association observed herein between organic food frequency and cancer risk is that the prohibition of synthetic pesticides in organic farming leads to a lower frequency or an absence of contamination in organic foods compared with conventional foods46,47 and results in significant reductions in pesticide levels in urine.48 In 2015, based on experimental and population studies, the International Agency for Research on Cancer49 recognized the carcinogenicity of certain pesticides (malathion and diazinon were classified as probably carcinogenic for humans [group 2A], and tetrachlorvinphos and parathion were classified as possibly carcinogenic for humans [group 2B]). While there is a growing body of evidence supporting a role of occupational exposure to pesticides for various health outcomes and specifically for cancer development,4,50,51 there have been few large-scale studies conducted in the general population, for whom diet is the main source of pesticide exposure.52 It now seems important to evaluate chronic effects of low-dose pesticide residue exposure from the diet and potential cocktail effects at the general population level. In particular, further research is required to identify which specific factors are responsible for potential protective effects of organic food consumption on cancer risk.

In our study, we observed a lower risk of breast cancer among high organic food consumers. This finding may be interpreted in light of a recent review on the link between breast cancer and various chemicals, which concluded that exposure to chemicals (including pesticides) may lead to an increased risk of developing breast cancer.53 The inverse association found between NHL and organic food consumption in our study appears to be in line (under the pesticide-harm hypothesis) with a meta-analysis54 reporting that exposure to malathion, terbufos, and diazinon led to a 22% increased risk of NHL.

Possible underlying mechanistic pathways relating pesticide residues and carcinogenicity include structural DNA damage, as well as functional damage through epigenetic mechanisms. Other mechanisms, such as disorders at the mitochondrion or endoplasmic reticulum level or disturbances of factors implied in maintaining cell homeostasis, are also frequently mentioned.55 Because endocrine-disrupting pesticides mimic estrogen function, such properties may also be involved in breast carcinogenesis.56

When considering different subgroups, the results herein were no longer statistically significant in younger adults, men, participants with only a high school diploma and with no family history of cancer, never smokers and current smokers, and participants with a high overall dietary quality, while the strongest association was observed among obese individuals (although the 95% CI was large). The absence of significant results in certain strata may be associated with limited statistical power. Regarding the latter association, previous occupational data have indicated a potential interaction between obesity and pesticide use on cancer risk.57 It can be hypothesized that obese individuals with metabolic disorders may be more sensitive to potential chemical disruptors, such as pesticides.

Negative associations were observed herein between the risk of cancer and combining both low to medium diet quality and high frequency of organic food consumption. The association between cancer risk and combining both a high-quality diet and high frequency of organic food consumption approached statistical significance. One hypothesis may be that higher intake of pesticide-contaminated products13 may partly counterbalance the beneficial role of high-quality foods among individuals with a high dietary quality.

While organic food (on confirmation of our findings) may be important to reduce the risk of specific cancers, the high price of such foods remains an important hurdle. Indeed, organic foods remain less affordable than corresponding conventional products, and high prices are a major obstacle for buying organic foods.

Limitations

Some limitations of our study should be noted. First, our analyses were based on volunteers who were likely particularly health-conscious individuals, thus limiting the generalizability of our findings. NutriNet-Santé participants are more often female, are well educated, and exhibit healthier behaviors compared with the French general population.7,8 These factors may may have led to a lower cancer incidence herein than the national estimates, as well as higher levels of organic food consumption in our sample.

Second, although organic food frequencies in our study were collected using a specific questionnaire providing more precise data than earlier studies, strictly quantitative consumption data were not available. Some misclassification in the organic food score intermediate quartiles herein cannot be excluded.

Third, our follow-up time was short, which may have limited the causal inference, as well as the statistical power for specific sites, such as colorectal cancer. However, more than 1300 cancer cases were registered in this study. The investigation of longer-term effects, while accounting for exposure change, will be insightful as part of the cohort’s follow-up. Nevertheless, analyses that were performed by removing cases occurring during the first 2 years of follow-up did not substantially modify our findings.

Fourth, the observed associations may have been influenced by residual confounding. Although we accounted for a wide range of covariates, including major confounders associated with organic food consumption (eg, dietary patterns and other lifestyle factors), residual confounding resulting from unmeasured factors or inaccuracy in the assessment of some covariates cannot be totally excluded. Nutritional covariates, such as the mPNNS-GS or dietary pattern factors, were assessed based on a high level of precision (59 food groups), while the exposure of interest was calculated using a simple scoring method. This may have resulted in a potential bias toward attenuated associations of the exposure of interest. The sensitivity analysis performed applying a simplified, plant-derived organic food score (to account for variations in pesticide exposure across food groups) did not show stringent differences compared with the original organic food score except for breast cancer.

Fifth, we cannot exclude the nondetection of some cancer cases. This is despite the use of a multisource strategy for case ascertainment.

Strengths of our study include its prospective design and the large sample size, allowing us to conduct stratified analyses for different cancer sites. In addition, we used a detailed questionnaire on organic food frequency and clinical validation of cancer cases.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that higher organic food consumption is associated with a reduction in the risk of overall cancer. We observed reduced risks for specific cancer sites (postmenopausal breast cancer, NHL, and all lymphomas) among individuals with a higher frequency of organic food consumption. Further prospective studies using accurate exposure data are necessary to confirm these results and should integrate a large number of individuals. If confirmed, our results appear to suggest that promoting organic food consumption in the general population could be a promising preventive strategy against cancer.

eTable 1. PNNS-GS: Components and Scores According to PNNS Recommendations

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics Among Included and Excluded Participants, NutriNet-Santé Cohort, France

eTable 3. Parameter Estimates and Hazard Ratios (HR) With 95% Confidence Intervals (95% CI) for All Variables Included in the Main Model, NutriNet-Santé Cohort, France

eTable 4. Factor Loadings of the Two First PCA-Extracted Factors, NutriNet-Santé Cohort, France

eTable 5. Dietary Characteristics of Participants According to Quartiles of the Organic Score, NutriNet-Santé Cohort, France

eTable 6. Multivariable Associations Between the Organic Food Score (Modeled as a Continuous Variable and as Quartiles) and Overall Cancer Risk, Additional Models, NutriNet-Santé Cohort, France, 2009 to 2016

eTable 7. Parameter Estimates and Hazard Ratios (HR) With 95% Confidence Intervals (95% CI) for a ‘Tandem’ Variable Combining Both Different Diet Quality Levels (Reflected by the mPNNS-GS) and Organic Food Consumption Frequencies, NutriNet-Santé Cohort, France, 2009-2016

eAppendix. Cancer Risk Modeling

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359-E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . International Agency for Research on Cancer. https://www.iarc.fr/. Accessed August 4, 2017.

- 3.Dossier: par INSERM [salle de presse]. Pesticides: effets sur la santé, une expertise collective de l’INSERM. http://presse.inserm.fr/pesticides-effets-sur-la-sante-une-expertise-collective-de-linserm/8463/. Published June 13, 2013. Accessed August 21, 2016.

- 4.Mostafalou S, Abdollahi M. Pesticides: an update of human exposure and toxicity. Arch Toxicol. 2017;91(2):549-599. doi: 10.1007/s00204-016-1849-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graillot V, Takakura N, Hegarat LL, Fessard V, Audebert M, Cravedi JP. Genotoxicity of pesticide mixtures present in the diet of the French population. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2012;53(3):173-184. doi: 10.1002/em.21676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.IFOAM EU and FiBL . Organic in Europe: prospects and developments: 2016. https://shop.fibl.org/CHen/mwdownloads/download/link/id/767/?ref=1. Published 2016. Accessed September 3, 2017.

- 7.Andreeva VA, Salanave B, Castetbon K, et al. Comparison of the sociodemographic characteristics of the large NutriNet-Santé e-cohort with French Census data: the issue of volunteer bias revisited. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(9):893-898. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-205263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andreeva VA, Deschamps V, Salanave B, et al. Comparison of dietary intakes between a large online cohort study (Etude NutriNet-Santé) and a nationally representative cross-sectional study (Etude Nationale Nutrition Santé) in France: addressing the issue of generalizability in e-epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;184(9):660-669. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughner RS, McDonagh P, Prothero A, Shultz CJ, Stanton J. Who are organic food consumers? a compilation and review of why people purchase organic food. J Consum Behav. 2007;6(2-3):94-110. doi: 10.1002/cb.210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Padilla Bravo C, Cordts A, Schulze B, Spiller A. Assessing determinants of organic food consumption using data from the German National Nutrition Survey II. Food Qual Prefer. 2013;28(1):60-70. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2012.08.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Règlement (CE) No . 834/2007. Du Conseil. Du 28 Juin 2007: relatif à la production biologique et à l'étiquetage des produits biologiques et abrogeant le règlement (CEE) No. 2092/91. http://www.agencebio.org/sites/default/files/upload/documents/3_Espace_Pro/RCE_BIO_834_2007_oct08.pdf. Published 2007. Accessed July 18, 2016.

- 12.Barański M, Średnicka-Tober D, Volakakis N, et al. Higher antioxidant and lower cadmium concentrations and lower incidence of pesticide residues in organically grown crops: a systematic literature review and meta-analyses. Br J Nutr. 2014;112(5):794-811. doi: 10.1017/S0007114514001366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.European Food Safety Authority . Monitoring data on pesticide residues in food: results on organic versus conventionally produced food. EFSA Support Publ. 2018;15(4):1397E. https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/supporting/pub/en-1397. Accessed April 26, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curl CL, Beresford SAA, Fenske RA, et al. Estimating pesticide exposure from dietary intake and organic food choices: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123(5):475-483. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oates L, Cohen M, Braun L, Schembri A, Taskova R. Reduction in urinary organophosphate pesticide metabolites in adults after a week-long organic diet. Environ Res. 2014;132:105-111. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.European Commission. EU: pesticides database. http://ec.europa.eu/food/plant/pesticides/eu-pesticides-database/public/. Published 2016. Accessed August 20, 2016.

- 17.Kim S, Thiessen PA, Bolton EE, et al. PubChem substance and compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D1202-D1213. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bradbury KE, Balkwill A, Spencer EA, et al. ; Million Women Study Collaborators . Organic food consumption and the incidence of cancer in a large prospective study of women in the United Kingdom. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(9):2321-2326. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kesse-Guyot E, Baudry J, Assmann KE, Galan P, Hercberg S, Lairon D. Prospective association between consumption frequency of organic food and body weight change, risk of overweight or obesity: results from the NutriNet-Santé study. Br J Nutr. 2017;117(2):325-334. doi: 10.1017/S0007114517000058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Torjusen H, Brantsæter AL, Haugen M, et al. Reduced risk of pre-eclampsia with organic vegetable consumption: results from the prospective Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(9):e006143. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisinger-Watzl M, Wittig F, Heuer T, Hoffmann I. Customers purchasing organic food: do they live healthier? results of the German National Nutrition Survey II. Eur J Nutr Food Saf. 2015;5(1):59-71. doi: 10.9734/EJNFS/2015/12734 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baudry J, Allès B, Péneau S, et al. Dietary intakes and diet quality according to levels of organic food consumption by French adults: cross-sectional findings from the NutriNet-Santé cohort study. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(4):638-648. doi: 10.1017/S1368980016002718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petersen SB, Rasmussen MA, Strøm M, Halldorsson TI, Olsen SF. Sociodemographic characteristics and food habits of organic consumers: a study from the Danish National Birth Cohort. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(10):1810-1819. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012004119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simões-Wüst AP, Moltó-Puigmartí C, van Dongen MC, Dagnelie PC, Thijs C. Organic food consumption during pregnancy is associated with different consumer profiles, food patterns and intake: the KOALA Birth Cohort Study. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(12):2134-2144. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017000842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hercberg S, Castetbon K, Czernichow S, et al. The NutriNet-Santé study: a web-based prospective study on the relationship between nutrition and health and determinants of dietary patterns and nutritional status. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:242. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Touvier M, Méjean C, Kesse-Guyot E, et al. Comparison between web-based and paper versions of a self-administered anthropometric questionnaire. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(5):287-296. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9433-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vergnaud AC, Touvier M, Méjean C, et al. Agreement between web-based and paper versions of a socio-demographic questionnaire in the NutriNet-Santé study. Int J Public Health. 2011;56(4):407-417. doi: 10.1007/s00038-011-0257-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lassale C, Péneau S, Touvier M, et al. Validity of web-based self-reported weight and height: results of the NutriNet-Santé study. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(8):e152. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lassale C, Castetbon K, Laporte F, et al. Validation of a web-based, self-administered, non-consecutive-day dietary record tool against urinary biomarkers. Br J Nutr. 2015;113(6):953-962. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515000057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lassale C, Castetbon K, Laporte F, et al. Correlations between fruit, vegetables, fish, vitamins, and fatty acids estimated by web-based nonconsecutive dietary records and respective biomarkers of nutritional status. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(3):427-438.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Touvier M, Kesse-Guyot E, Méjean C, et al. Comparison between an interactive web-based self-administered 24 h dietary record and an interview by a dietitian for large-scale epidemiological studies. Br J Nutr. 2011;105(7):1055-1064. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510004617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Le Moullec N, Deheeger M, Preziosi P, et al. Validation of the photography manual of servings used in dietary collection in the SU.VI.MAX study [in French]. Cah Nutr Diét. 1996;31(3):158-164. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Moubarac JC, Levy RB, Louzada MLC, Jaime PC. The UN Decade of Nutrition, the NOVA food classification and the trouble with ultra-processing. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(1):5-17. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017000234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fiolet T, Srour B, Sellem L, et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and cancer risk: results from NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort. BMJ. 2018;360:k322. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Étude NutriNet-Santé . Table de Composition des Aliments. Paris, France: Economica; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Black AE. Critical evaluation of energy intake using the Goldberg cut-off for energy intake:basal metabolic rate: a practical guide to its calculation, use and limitations. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24(9):1119-1130. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Estaquio C, Kesse-Guyot E, Deschamps V, et al. Adherence to the French Programme National Nutrition Santé Guideline Score is associated with better nutrient intake and nutritional status. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(6):1031-1041. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.INSEE . Definitions, methods, and quality. http://www.insee.fr/en/methodes/. Published 2009. Accessed February 23, 2015.

- 40.Hagströmer M, Oja P, Sjöström M. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ): a study of concurrent and construct validity. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9(6):755-762. doi: 10.1079/PHN2005898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.World Health Organization . International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd10cm.htm. Accessed August 30, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miettinen OS. Proportion of disease caused or prevented by a given exposure, trait or intervention. Am J Epidemiol. 1974;99(5):325-332. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yusof AS, Isa ZM, Shah SA. Dietary patterns and risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review of cohort studies (2000-2011). Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(9):4713-4717. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.9.4713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bertuccio P, Rosato V, Andreano A, et al. Dietary patterns and gastric cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(6):1450-1458. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brennan SF, Cantwell MM, Cardwell CR, Velentzis LS, Woodside JV. Dietary patterns and breast cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(5):1294-1302. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barański M, Srednicka-Tober D, Volakakis N, et al. Higher antioxidant and lower cadmium concentrations and lower incidence of pesticide residues in organically grown crops: a systematic literature review and meta-analyses. Br J Nutr. 2014;112(5):794-811. doi: 10.1017/S0007114514001366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith-Spangler C, Brandeau ML, Olkin I, Bravata DM. Are organic foods safer or healthier? Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(4):297-300. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Science and Technology Options Assessment . Human health implications of organic food and organic agriculture. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2016/581922/EPRS_STU%282016%29581922_EN.pdf. Accessed May 28, 2017.

- 49.Guyton KZ, Loomis D, Grosse Y, et al. ; International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group, IARC . Carcinogenicity of tetrachlorvinphos, parathion, malathion, diazinon, and glyphosate. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(5):490-491. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70134-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Androutsopoulos VP, Hernandez AF, Liesivuori J, Tsatsakis AM. A mechanistic overview of health associated effects of low levels of organochlorine and organophosphorous pesticides. Toxicology. 2013;307:89-94. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2012.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim KH, Kabir E, Jahan SA. Exposure to pesticides and the associated human health effects. Sci Total Environ. 2017;575:525-535. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nougadère A, Sirot V, Kadar A, et al. Total diet study on pesticide residues in France: levels in food as consumed and chronic dietary risk to consumers. Environ Int. 2012;45:135-150. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2012.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gray JM, Rasanayagam S, Engel C, Rizzo J. State of the evidence 2017: an update on the connection between breast cancer and the environment. Environ Health. 2017;16(1):94. doi: 10.1186/s12940-017-0287-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hu L, Luo D, Zhou T, Tao Y, Feng J, Mei S. The association between non-Hodgkin lymphoma and organophosphate pesticides exposure: a meta-analysis. Environ Pollut. 2017;231(pt 1):319-328. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mostafalou S, Abdollahi M. Pesticides and human chronic diseases: evidences, mechanisms, and perspectives. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013;268(2):157-177. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Macon MB, Fenton SE. Endocrine disruptors and the breast: early life effects and later life disease. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2013;18(1):43-61. doi: 10.1007/s10911-013-9275-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Andreotti G, Hou L, Beane Freeman LE, et al. Body mass index, agricultural pesticide use, and cancer incidence in the Agricultural Health Study cohort. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21(11):1759-1775. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9603-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. PNNS-GS: Components and Scores According to PNNS Recommendations

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics Among Included and Excluded Participants, NutriNet-Santé Cohort, France

eTable 3. Parameter Estimates and Hazard Ratios (HR) With 95% Confidence Intervals (95% CI) for All Variables Included in the Main Model, NutriNet-Santé Cohort, France

eTable 4. Factor Loadings of the Two First PCA-Extracted Factors, NutriNet-Santé Cohort, France

eTable 5. Dietary Characteristics of Participants According to Quartiles of the Organic Score, NutriNet-Santé Cohort, France

eTable 6. Multivariable Associations Between the Organic Food Score (Modeled as a Continuous Variable and as Quartiles) and Overall Cancer Risk, Additional Models, NutriNet-Santé Cohort, France, 2009 to 2016

eTable 7. Parameter Estimates and Hazard Ratios (HR) With 95% Confidence Intervals (95% CI) for a ‘Tandem’ Variable Combining Both Different Diet Quality Levels (Reflected by the mPNNS-GS) and Organic Food Consumption Frequencies, NutriNet-Santé Cohort, France, 2009-2016

eAppendix. Cancer Risk Modeling