Abstract

This study examines the presence and extent of undeclared financial conflicts of interest among authors of clinical practice guidelines related to high-revenue medications.

The presence of financial conflicts of interest in clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) may affect the objectivity of these documents. Although the National Academy of Medicine has created policies to limit industry influence on the development of CPGs, guidelines rarely adhere to these policies.1 Moreover, CPG authors may have undeclared financial conflicts of interest.2 We hypothesized that undeclared industry payments would be highly prevalent among authors of CPGs related to high-revenue medications, and we quantified the presence and extent of these payments.

Methods

In this study, conducted from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2017, we identified the top 10 revenue medications of 2016 using the pharmaceutical information website PharmaCompass (https://www.pharmacompass.com/) and verified this information with Securities and Exchange Commission documents and company reports. We identified CPGs through the National Guideline Clearinghouse based on clinical indications for medications and selected CPGs endorsed by a national organization based in the United States and published from 2013 to 2017. For each author, we categorized financial conflicts of interest based on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Open Payments (CMS-OP) definitions of general (eg, consulting fees) or research payments (https://www.cms.gov/OpenPayments/About/Natures-of-Payment.html). The CMS-OP website publishes payments made by pharmaceutical companies to US-based physicians. This study used publicly available data. A waiver of approval was provided by the St Michael’s Hospital Research Ethics Board.

We searched for authors on the CMS-OP website to identify payments not declared in the CPG. We only included US-based physicians in our study sample, defined as authors with CMS-OP profiles. We limited our search to the CPG publication year and the year prior. We assessed each guideline for adherence to 3 National Academy of Medicine standards: written disclosure of all potential financial conflicts of interest; appointing committee chairs with no financial conflicts of interest; and limiting guideline authors with financial conflicts of interest to less than 50% of the panel.3

Results

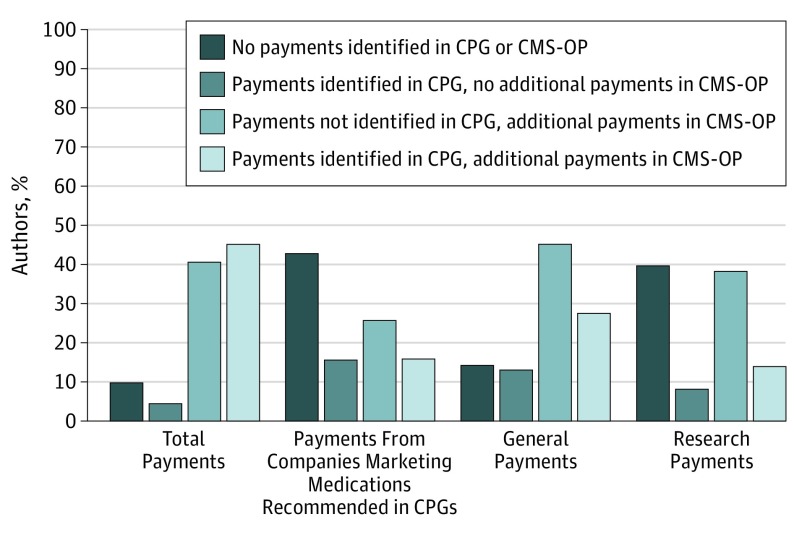

We identified 18 CPGs that provided recommendations for 10 high-revenue medications, written by 160 authors who were US-based physicians (Table). A total of 79 authors (49.4%) declared receipt of a payment in the CPG or supplemental materials, with 50 (31.3%) declaring receipt of payments from companies marketing 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications recommended in the CPG. An additional 41 authors (25.6%) were found to have received but not disclosed receipt of payments from companies marketing 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications recommended within the CPGs. Thus, in total, 91 authors (56.9%) were found to have financial conflicts of interest (Figure).

Table. Characteristics of Clinical Practice Guidelines.

| Guideline | Medication(s); Disease Indication | Subspecialty Society | Industry Paymentsa | No. of NAM Standards Met/Total No. of NAM Standardsb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Authors With Payments/Total No. of Authors | No. of Chairs With Payments/Total No. of Chairs | ||||

| 1 | Adalimumab, etancercept, infliximab, rituximab; rheumatoid arthritis | American College of Rheumatologyc | 13/16 | 1/1 | 0/3 |

| 2 | Adalimumab, etancercept, infliximab; juvenile idiopathic arthritis | American College of Rheumatologyc | 4/10 | 1/2 | 1/3 |

| 3 | Adalimumab, etancercept, infliximab; ankylosing spondylitis | American College of Rheumatology, Spondylitis Association of America, Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Networkc | 12/15 | 0/1 | 1/3 |

| 4 | Adalimumab, infliximab; Crohn disease | American Gastroenterological Associationd | 1/11 | 0/1 | 2/3 |

| 5 | Adalimumab, infliximab; Crohn disease after surgical resection | American Gastroenterological Associationd | 4/11 | 0/1 | 2/3 |

| 6 | Ledipasvir-sofosbuvir; hepatitis C | American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Infectious Diseases Society of Americae | 15/20 | 4/4 | 0/3 |

| 7 | Bevacizumab; non–small cell lung cancer | American College of Chest Physiciansf | 4/6 | 1/1 | 0/3 |

| 8 | Bevacizumab; non–small cell lung cancer | American Society of Clinical Oncologyc | 6/10 | 2/2 | 0/3 |

| 9 | Bevacizumab; glioblastoma | American Association of Neurological Surgeons, Congress of Neurological Surgeonsg | 1/6 | 1/1 | 1/3 |

| 10 | Trastuzumab; HER2-negative breast cancer | American Society of Clinical Oncologyc | 5/8 | 1/2 | 0/3 |

| 11 | Trastuzumab; HER2-negative breast cancer | American Society of Clinical Oncologyc | 4/7 | 2/2 | 0/3 |

| 12 | Trastuzumab; HER2-positive breast cancer | American Society of Clinical Oncologyc | 7/11 | 2/2 | 0/3 |

| 13 | Insulin glargine; diabetes in pregnancy | The Endocrine Societyd | 1/3 | 1/1 | 1/3 |

| 14 | Insulin glargine; type 1 diabetes | American Diabetes Associationh | 5/6 | 1/2 | 0/3 |

| 15 | Insulin glargine; type 2 diabetes | American Diabetes Associationh | 5/6 | 1/2 | 0/3 |

| 16 | Rivaroxaban; venous thromboembolic disease | American College of Chest Physiciansf | 3/7 | 1/1 | 1/3 |

| 17 | Rivaroxaban; atrial fibrillation | American Academy of Family Physiciansf | 0/3 | 0/1 | 2/3 |

| 18 | Rivaroxaban; atrial fibrillation | American Academy of Neurologyc | 1/4 | 1/1 | 1/3 |

Abbreviations: CMS-OP, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Open Payments; NAM, National Academy of Medicine.

Represents the total number of author and chairs, who are US-based physicians with payments from pharmaceutical companies marketing 1 of the top 10 medications in clinical practice guidelines, considering both payments declared in the guideline and additional payments identified through CMS-OP.

The NAM standards assessed are (1) written disclosure of all potential financial conflicts of interest, (2) appointing committee chairs with no financial conflicts of interest, and (3) limiting guideline authors with financial conflicts of interest to less than 50% of the panel.

Guideline chairs and co-chairs and more than 50% of guideline development group should be free of conflicts of interest relevant to the subject matter of the of the project for at least 1 year prior to the guideline development to 1 year after completion.

Guideline chairs and co-chairs and more than 50% of guideline development group members should be free of commercial, noncommercial, intellectual, institutional, and patient or public activities pertinent to the potential scope of the clinical practice guideline. No timeline provided.

Guideline chairs and co-chairs and more than 50% of guideline development group members should be free of personal (ie, direct payment to the individual) financial conflicts that may result in financial benefit prior to appointment onto the guideline panel for 1 year prior to the guideline development.

Guideline chairs and co-chairs and more than 50% of members should be free of conflicts of interest, defined as any relationship that has the potential to bias, or that might be reasonably perceived by others to bias, an individual’s judgment, for 3 years prior to guideline development.

Not stated.

Guideline chairs and co-chairs and more than 50% of guideline development group members should not receive industry funding as an employee, consultant, or principal investigator specific to the activities of the committee or groups. Those with industry relationships should recuse themselves from voting on any decision.

Figure. Payments Received by Authors of Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) Recommending High-Revenue Medications.

Data are stratified by payment type. CMS-OP indicates Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Open Payments.

Among all authors, the median value of undeclared payments from companies marketing 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications recommended in the CPGs was $522 (interquartile range, $0-$40 444) from 2 companies (interquartile range, 0-4). With respect to adherence to National Academy of Medicine standards, no CPGs had complete written disclosure of all potential financial conflicts of interest, 4 appointed chairs without financial conflicts of interest, and 8 limited authors with financial conflicts of interest to less than 50% of the panel.

Discussion

Authors of CPGs related to high-revenue medications have a substantial number of undeclared payments from industry, including those from pharmaceutical companies that market the medications recommended in those CPGs. In addition, most guidelines fail to adhere to national standards for financial conflicts of interest in CPGs. Guidelines related to high-revenue medications may be at especially high risk of having authors with financial conflicts of interest because pharmaceutical companies expend considerable resources marketing their top products.4 This marketing may take the form of payments to physicians, which have been shown to affect clinical decision making.5

This study is limited by potential inaccuracies in CMS-OP reporting, which are rarely corrected,6 and lack of generalizability outside the United States. In addition, the CMS-OP website began publishing data from mid-2013. Since we collected only several months of CMS-OP data for guidelines published in 2013, we may have underestimated the financial conflicts of interest for these guidelines. Finally, we did not have access to guideline voting records and thus did not know when conflicted panel members recommended against a medication or recused themselves from voting.

References

- 1.Sox HC. Conflict of interest in practice guidelines panels. JAMA. 2017;317(17):1739-1740. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.2701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neuman J, Korenstein D, Ross JS, Keyhani S. Prevalence of financial conflicts of interest among panel members producing clinical practice guidelines in Canada and United States: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2011;343:d5621. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graham R, Mancher M, Wolman DM. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kornfield R, Donohue J, Berndt ER, Alexander GC. Promotion of prescription drugs to consumers and providers, 2001-2010. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e55504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brax H, Fadlallah R, Al-Khaled L, et al. . Association between physicians’ interaction with pharmaceutical companies and their clinical practices: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santhakumar S, Adashi EY. The Physician Payment Sunshine Act: testing the value of transparency. JAMA. 2015;313(1):23-24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.15472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]