Abstract

Importance

Most states have adopted the routine use of a prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) to curb overprescribing of opioids. The American College of Surgeons promotes the use of these programs as a “guiding principle to curb the opioid epidemic.” However, there is a paucity of data on the effects of the use of these programs for surgical patient populations.

Objective

To determine the association of the mandatory use of a PDMP with the opioid prescribing practices for patients undergoing general surgery.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A prospective observational cohort study was conducted at an academic hospital in New Hampshire among 1057 patients undergoing representative elective general surgical procedures from July 1, 2016, to June 30, 2017.

Exposures

New state legislation mandated the use of a PDMP and opioid risk-assessment tool for all patients receiving an outpatient opioid prescription in New Hampshire beginning January 1, 2017. The electronic medical prescribing system was modified to facilitate and support compliance with the new requirements.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Change in opioid prescribing practices after January 1, 2017, and time to complete PDMP requirements.

Results

Among the 1057 patients (569 women [53.8%] and 488 men [46.2%]; mean [SD] age, 56.8 [15.4] years), the percentage of patients prescribed opioids after surgery did not decrease significantly (429 of 536 [80.0%] before the new requirements vs 401 of 521 [77.0%] after the requirements; P = .29). The mean number of opioid pills prescribed decreased from 30.8 to 24.0 (22.1%) in the 6 months prior to the mandatory PDMP requirement; the rate of decrease was actually less (from 22.8 to 21.9 pills [3.9%]) in the 6 months after the legislation. These new requirements did not identify any high-risk patients who subsequently were not prescribed opioids. The query and opioid abuse risk calculator together took a median time of 7 minutes (range, 2-17 minutes) to complete.

Conclusions and Relevance

A mandatory PDMP query requirement was not significantly associated with the overall rate of opioid prescribing or the mean number of pills prescribed for patients undergoing general surgical procedures. In no cases was a high-risk patient identified, leading to avoidance of an opioid prescription. A PDMP can be a useful adjunct in certain settings, but this study found that it did not have the intended effect in a population undergoing elective surgical procedures. Legislative efforts to mandate PDMP use should be targeted to populations in which benefit can be demonstrated.

This pre-post cohort study examines the association of the mandatory use of a prescription drug monitoring program with the opioid prescribing practices for patients undergoing elective general surgical procedures at an academic hospital.

Key Points

Question

How does mandatory use of a prescription drug monitoring program change the prescribing practices for patients undergoing elective general surgery?

Findings

In this pre-post cohort study of 1057 patients, prescribing practices were compared before and after New Hampshire legislation mandating the use of a prescription drug monitoring program that took effect January 1, 2017. There was no significant change in the rate of opioid prescriptions written or the mean number of pills prescribed.

Meaning

It seems that efforts to curb overprescribing of opioids should be evidence based and should show clinical benefit prior to mandatory implementation, and that patients undergoing elective surgical procedures should be considered differently when developing opioid legislation.

Introduction

The US population consumes more opioid medication than any other nation.1 Opioid overdose is now the leading cause of injury-related death in the United States, and the incidence of opioid overdose has quadrupled in the past 15 years, reaching nearly 19 000 deaths annually.2,3 Opioid overdose has been linked to increasing rates of opioid prescriptions, which have similarly quadrupled since 1999.4 Prescriptions written by surgeons have contributed significantly to the epidemic of opioid abuse and opioid-related deaths.2,5 Opioid diversion is recognized as a major adverse effect of opioid overprescribing. It is estimated that 71% of long-term opioid users receive their medications through methods of diversion.6 More than 5 million individuals in the US report current opioid abuse (within 30 days), and 10.3 million individuals have reported opioid abuse during their lifetime.3,7,8 The US Food and Drug Administration has stated that “[u]ntil clinicians stop prescribing opioids far in excess of the clinical need, this crisis will continue unabated.”9(p1483)

There have been significant surgeon-led efforts in recent years to define safe and appropriate opioid prescribing practices for surgical patients.10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 For example, by gathering data on the home use of opioids, one study derived specific opioid prescribing guidelines after routine outpatient general surgical procedures.10 Educational efforts based on these data led to a 53% decrease in the number of opioid pills prescribed at hospital discharge.11 One recent study showed that opioid use in the 24 hours prior to hospital discharge is the best factor associated with outpatient opioid use after a surgical procedure that requires inpatient admission.18

In addition, there has been growing enthusiasm from local, state, and federal agencies to address the problem of overprescription of opioids through efforts including drug take-back programs, prescriber education, and prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs). As of 2017, a total of 49 of 50 states now use the PDMP, a national database used by medical professionals and pharmacies to track patient use of controlled substances.1 In their Statement on the Opioid Use Epidemic, the American College of Surgeons recommends the use of PDMPs for surgical patients as a “guiding principle” to address the opioid overuse epidemic.19 Beginning January 1, 2017, New Hampshire state law dictated that all health care professionals run a PDMP query and complete an opioid abuse risk-assessment calculator for all patients receiving an opioid prescription, including those undergoing a surgical procedure. At our institution, a moderate-sized academic hospital in New Hampshire, the administration additionally requires that an informed consent process be completed for every patient undergoing a surgical procedure who receives an opioid prescription.

Early observational data after PDMP implementation in populations of outpatients with chronic pain have been promising, with decreased “doctor shopping” and opioid-related deaths.20,21,22,23,24,25,26 However, in other patient populations, such as those who are treated at the emergency department, use of the PDMP is sporadic and the clinical effects have been mixed.27,28,29,30,31,32 For example, Weiner et al31 demonstrated that PDMP queries in an emergency department setting changed prescribing behavior in only 9.5% of cases and resulted in more opioids prescribed overall. Surveys of physicians have found that many find PDMP queries to be rarely or never helpful, very difficult to use, and a substantial additional time burden.33 To our knowledge, there are no studies of the effect of PDMP use in a surgical population when postoperative pain is expected and opioid prescribing is routinely indicated. Furthermore, no educational programs or standards exist to guide prescribers in how to interpret or use the information obtained through the PDMP.

To this aim, we attempted to determine if PDMP queries identified the intended patients at high risk of opioid abuse and to investigate how prescribing practices changed as a result of the use of a PDMP. We estimated that opioid prescription rates would decrease substantially after the January 1, 2017, implementation of this new legislation.

Methods

Prospectively collected data were obtained for the period from July 1, 2016, to June 30, 2017, at our institution, a moderately sized academic hospital in New Hampshire. The study period included 6 months before and 6 months after a change in New Hampshire legislation requiring a PDMP query and opioid abuse risk calculator be completed for all patients receiving an outpatient opioid prescription for acute pain. Patients undergoing a representative range of common inpatient and outpatient general surgical procedures were identified by Current Procedural Terminology code. Inpatient procedures included bariatric and foregut, colon, liver, pancreas, and ventral hernia operations. Outpatient operations included inguinal hernia (open and laparoscopic) and cholecystectomy. The Dartmouth Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects approved this study and waived the requirement for consent owing to the minimal risk level of the study.

Demographic information, procedure type, and data on whether a PDMP query and/or opioid risk assessment was performed were collected. Descriptive statistics, the t test, and χ2 analyses were performed. Two-sided P values were calculated and were considered significant at P < .05. Observational data of clinical encounters were obtained to determine the additional amount of time required to complete these requirements. Eight representative surgical clinicians (6 surgical residents and 2 faculty members) underwent direct observation during 21 patient encounters to determine the time required to complete the additional requirements. These surgical clinicians were blinded to the data being collected while being observed.

We identified a subset of patients for whom a PDMP query was performed but an opioid prescription was not written. For these patients, we repeated the PDMP query to assess if these individual patients had findings indicating a high risk of opioid abuse that would discourage a surgical clinician from writing an opioid prescription. Findings indicating high risk of opioid abuse were defined as multiple or frequent opioid prescriptions being obtained from multiple clinicians or being filled at different pharmacies in the 6 months prior to the index operation.

Our institution uses an electronic medical record system. The PDMP query is accessed via a hyperlink to an external website requiring a separate, user-specific login and password. The risk calculator is embedded within the electronic medical record, and completion of each of these steps is documented within the electronic medical record. If the prescriber fails to document the query, a decision support interruptive alert appears that informs the prescriber of the mandatory requirement to perform the query. The prescription will not be disbursed unless the prescriber affirms that the query was performed.

Current practices for postoperative pain management at our institution vary by procedure and service but are often multimodal and focused on minimization of the use of narcotics. Scheduled acetaminophen with or without ibuprofen is prescribed for most patients. Our anesthesia staff are facile with regional anesthesia (eg, transverse abdominis plane blocks) for appropriate abdominal operations.

Results

Opioid Prescription Rate

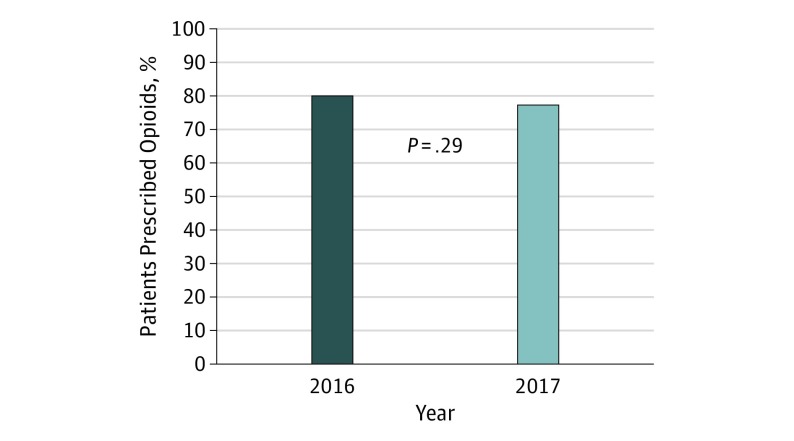

A total of 1057 patients undergoing routine general surgical procedures were included in the analysis; 536 patients underwent surgery before the legislation took effect (July 1 to December 31, 2016), and 521 patients underwent surgery after the legislative changes (January 1 to June 30, 2017). There was no significant change in case mix between the 2016 and 2017 groups (Table 1). No patients were excluded from the analysis. Figure 1 demonstrates that the percentage of patients who underwent elective surgical procedures and were given an opioid prescription at hospital discharge did not significantly change during the study period (429 of 536 [80.0%] before the new requirements vs 401 of 521 [77.0%] after the requirements; P = .29).

Table 1. Data on Representative General Surgical Procedures Included in the Study.

| Time Period | Bariatric and Foregut Surgery, No. | Colectomy, No. | Ventral Hernia Repair, No. | Hepatectomy, No. | Pancreatectomy, No. | Laparoscopic Inguinal Hernia Repair, No. | Open Inguinal Hernia Repair, No. | Cholecystectomy, No. | Total No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| July-December 2016 | 133 | 136 | 47 | 15 | 19 | 46 | 45 | 95 | 536 |

| January-June 2017 | 132 | 133 | 40 | 16 | 23 | 59 | 29 | 89 | 521 |

| Total | 265 | 269 | 87 | 31 | 42 | 105 | 74 | 184 | 1057 |

Figure 1. Patients Who Underwent an Elective Surgical Procedure and Were Given an Outpatient Opioid Prescription at Discharge Before and After Legislation Mandating Use of a Prescription Drug Monitoring Program.

Identification of High-Risk Patients

Although the overall prescription rate at hospital discharge did not change, we sought to determine if there were cases when a PDMP query and opioid abuse risk calculator led to withholding of an opioid prescription. Most patients who were not prescribed opioids did not have a PDMP query performed. However, we identified 8 patients who had a PDMP query performed, but they did not receive an opioid prescription. Relevant clinical details and PDMP query results for these patients are summarized in Table 2. Seven of the patients underwent inpatient operations. Six of the 7 inpatients had been weaned off opioids and did not require narcotics for pain control in the 24 hours prior to hospital discharge. One of the 7 inpatients had a recent history of stable longstanding opioid use for chronic pain covered by an agreement with their primary care physician, and the opioid dosage had been tapered down to her preexisting home regimen by the time of hospital discharge. The single outpatient in the series underwent a laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair and was offered an opioid prescription at the time of hospital discharge, but he refused the prescription. None of these 8 patients had a history of opioid abuse or was deemed to have high-risk behavior based on available clinical data, a PDMP search, and the opioid abuse risk calculator. The PDMP query and risk calculator did not lead to a prescription being withheld for any patient in our series.

Table 2. Data on Patients Who Had a Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) Query Performed but Did Not Receive an Opioid Prescriptiona.

| Patient No./Sex/Age, y | Procedure Type | PDMP Results (6 mo Prior to Surgery) | Clinical Notes Based on Medical Record |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1/M/57 | Laparoscopic inguinal hernia | No patient record in PDMP | Refused prescriptions at hospital discharge |

| 2/M/62 | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 1 Opioid prescription 3 wk prior to surgery for acute pancreatitis | Did not require opioids 24 h prior to hospital discharge |

| 3/F/68 | Hepatic wedge resection | No opioids prescribed within 6 mo of index operation | No inpatient opioids given |

| 4/M/70 | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | No patient record in PDMP | Did not require opioids 24 h prior to hospital discharge |

| 5/F/56 | Partial colectomy | Frequent routine prescriptions (single prescriber with regular fills consistent with pain contract) | Known long-term opioid use, tapered to dosage of home regimen prior to hospital discharge |

| 6/M/75 | Partial colectomy | No patient record in PDMP | Single opioid dose in 24 h prior to hospital discharge, none given on day of hospital discharge |

| 7/M/44 | Roux-en-Y gastric bypass | No opioids prescribed within 6 mo of index operation | Did not require opioids 24 h prior to hospital discharge |

| 8/F/67 | Total colectomy with ileostomy | No patient record in PDMP | Did not require opioids 24 h prior to hospital discharge |

No patient had a history of opioid abuse or misuse identified by review of medical records or by PDMP findings.

Mean Number of Opioid Pills Prescribed

We also evaluated whether the mean number of opioid pills prescribed was affected by the mandatory PDMP legislation. As shown in Figure 2A, the mean number of opioid pills prescribed was decreasing during the 6 months prior to the PDMP requirement. Overall, the mean number of pills prescribed decreased by 22.1% (from 30.8 to 24.0) between July and December 2016 (Figure 2A). There was no significant immediate decrement in the mean number of opioids prescribed in January 2017 when the requirement went into effect (Figure 2B). In the 6 months after use of the mandatory PDMP, the rate of decrease in the number of prescribed pills was less; the mean number of pills prescribed decreased only by 3.9% (from 22.8 to 21.9) between January and June 2017 (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Change in the Mean Number of Opioid Pills Prescribed During the Course of the Study.

A, The 6 months prior to the use of a mandatory prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP). B, The 6 months before and after the use of a mandatory PDMP. C, The 6 months after the use of a mandatory PDMP.

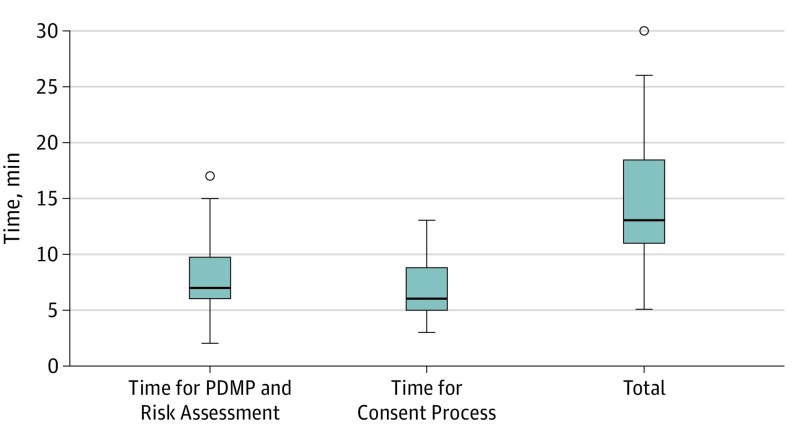

Additional Time to Complete Requirements

We quantified the amount of time needed to complete these additional requirements. Direct observation of 8 surgical clinicians during 21 patient encounters revealed a median time to complete the PDMP query and risk calculator together of 7 minutes (range, 2-17 minutes). An additional median time of 6 minutes (range, 4-15 minutes) was required to complete our institutional informed consent process (Figure 3). Together, these additional mandatory requirements for prescribing opioid medication to patients who underwent surgical procedures took 13 minutes for each patient.

Figure 3. Additional Time Required to Complete the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) Query and the Risk Assessment Tool and the Informed Consent Process .

Time is reported as a mean value with range (error bar) and interquartile range (shaded); the small circles indicate outliers.

Discussion

Opioid overprescribing is rampant, has deadly consequences, and continues to be of major concern in the United States. Prescriptions written by surgeons have contributed significantly to the epidemic of opioid overprescribing and opioid-related deaths.2,5 The use of a mandatory PDMP has been suggested to help curb overprescription by surgeons. However, while some patients may feign back pain in an attempt to obtain an opioid prescription in a walk-in clinic, it is highly unlikely that they will undergo a surgical procedure just to obtain opioids. Furthermore, if one identifies a patient with multiple undisclosed opioid prescriptions through a PDMP query, that patient will probably require at least as many initial postoperative opioid pills as an average patient owing to tolerance. Selective PDMP use for patients requesting refills may make the most sense for surgeons. In fact, in 1 survey, only 22% of surgeons thought that PDMP use should be mandatory.33 Many of those surveyed thought that it was rarely helpful and that it was a substantial time burden.

The intended effect of the PDMP query and risk calculator to avoid opioid prescriptions likely to be abused or diverted was not supported in our study. We found that there was no decrease in the percentage of patients who were given an opioid prescription for postoperative pain, and in no cases was a prescription withheld from a patient owing to risk factors for abuse or suspicious PDMP findings. The PDMP can be a useful tool for identifying patients who are doctor shopping and has been demonstrated to be useful for outpatient populations and individuals with chronic pain.25,26 However, the experience of pain for patients undergoing elective general surgical procedures is fundamentally different from that of individuals in these populations with demonstrated benefit from PDMP use. Patients who undergo elective surgical procedures experience unavoidable postoperative surgical pain, which is usually self-limited. Regardless of the patient’s recent history or risk factors for abuse, an opioid prescription is often still clinically indicated in this situation.

It is possible that a PDMP query requirement may not affect a surgeon’s decision to prescribe opioids to a particular patient, but it may lead surgeons to prescribe fewer opioids to that patient. Therefore, we compared the mean number of pills prescribed to patients after implementation of the mandatory PDMP requirement. We found that there was no dramatic decrease in opioid prescribing coincident with this requirement. The mean number of opioids prescribed was decreasing at our institution during the 6 months prior to this legislation (likely secondary to evidence-based recommendations and educational efforts to encourage appropriate prescribing11), and the rate of decrease was actually less once this PDMP requirement went into effect.

Our data do not support the use of a mandatory PDMP as a useful tool to curb opioid prescriptions written for patients undergoing general surgical procedures. In addition, these requirements create a significant additional burden of time and administrative responsibilities for surgical clinicians and trainees who already think that documentation requirements are excessive and compromise the time spent with patients.34 For example, the mean turnover time between operative cases at our outpatient surgical center is 15 minutes. The additional 7 minutes required to complete the PDMP query and risk calculator, or the additional 13 minutes if our institutional informed consent process is considered, makes meeting this turnover benchmark impossible when other required tasks must also be completed.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. It was performed at a single institution, and the surgeons at this institution had already been modifying their prescribing habits prior to the initiation of this new requirement.

Conclusions

For acute postsurgical pain, physician-led efforts have shown significant promise for addressing opioid overprescribing. Guidelines for opioid prescribing10,11,18 and increasing use of multimodal pain strategies35,36,37 are 2 examples of successful interventions to address opioid overprescribing to surgical patients. New legislative efforts must be practical, feasible, and not impede the workflow of surgical clinicians. More work must be done to understand the clinical implications of mandatory requirements to curb opioid overprescribing prior to implementation. A robust evidence base will guide legislative efforts that are effective and do not overly burden health care professionals.

References

- 1.Paulozzi LJ, Mack KA, Hockenberry JM. Variation among states in prescribing of opioid pain relievers and benzodiazepines—United States, 2012. J Safety Res. 2014;51:125-129. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2014.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Number and age-adjusted rates of drug-poisoning deaths involving opioid analgesics and heroin: United States, 1999-2014. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/health_policy/AADR_drug_poisoning_involving_OA_Heroin_US_2000-2014.pdf. Accessed August 20, 2017.

- 3.Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(2):154-163. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1508490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dart RC, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, et al. Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(3):241-248. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1406143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lev R, Lee O, Petro S, et al. Who is prescribing controlled medications to patients who die of prescription drug abuse? Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(1):30-35. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maxwell JC. The prescription drug epidemic in the United States: a perfect storm. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2011;30(3):264-270. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00291.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manchikanti L, Singh A. Therapeutic opioids: a ten-year perspective on the complexities and complications of the escalating use, abuse, and nonmedical use of opioids. Pain Physician. 2008;11(2)(suppl):S63-S88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manchikanti L, Helm S II, Fellows B, et al. Opioid epidemic in the United States. Pain Physician. 2012;15(3)(suppl):ES9-ES38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Califf RM, Woodcock J, Ostroff S. A proactive response to prescription opioid abuse. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(15):1480-1485. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1601307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill MV, McMahon ML, Stucke RS, Barth RJ Jr. Wide variation and excessive dosage of opioid prescriptions for common general surgical procedures. Ann Surg. 2017;265(4):709-714. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill MV, Stucke RS, McMahon ML, Beeman JL, Barth RJ Jr. An educational intervention decreases opioid prescribing after general surgical operations. Ann Surg. 2018;267(3):468-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bateman BT, Cole NM, Maeda A, et al. Patterns of opioid prescription and use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):29-35. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osmundson SS, Schornack LA, Grasch JL, Zuckerwise LC, Young JL, Richardson MG. Post discharge opioid use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):36-41. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim N, Matzon JL, Abboudi J, et al. A prospective evaluation of opioid utilization after upper-extremity surgical procedures: identifying consumption patterns and determining prescribing guidelines. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(20):e89. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.00614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar K, Gulotta LV, Dines JS, et al. Unused opioid pills after outpatient shoulder surgeries given current perioperative prescribing habits. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(3):636-641. doi: 10.1177/0363546517693665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodgers J, Cunningham K, Fitzgerald K, Finnerty E. Opioid consumption following outpatient upper extremity surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(4):645-650. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.01.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bates C, Laciak R, Southwick A, Bishoff J. Overprescription of postoperative narcotics: a look at postoperative pain medication delivery, consumption and disposal in urological practice. J Urol. 2011;185(2):551-555. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill MV, Stucke RS, Billmeier SE, Kelly JL, Barth RJ Jr. Guideline for discharge opioid prescriptions after inpatient general surgical procedures. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(6):996-1003. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American College of Surgeons Statement on the opioid abuse epidemic. https://www.facs.org/about-acs/statements/100-opioid-abuse. Published August 2, 2017. Accessed August 2, 2017.

- 20.Johnson H, Paulozzi L, Porucznik C, Mack K, Herter B; Hal Johnson Consulting and Division of Disease Control and Health Promotion, Florida Department of Health . Decline in drug overdose deaths after state policy changes—Florida, 2010-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(26):569-574. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Florida Department of Health Electronic-Florida online reporting of controlled substances evaluation: 2012-2013 prescription drug monitoring program annual report. http://www.floridahealth.gov/statistics-and-data/e-forcse/news-reports/_documents/2012-2013pdmp-annual-report.pdf. Published December 1, 2013. Accessed August 20, 2017.

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Trends in drug-poisoning deaths involving opioid analgesics and heroin: United States, 1999-2012. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/drug_poisoning/drug_poisoning.htm. Updated December 2, 2014. Accessed August 20, 2017.

- 23.Virginia Department of Health Professions Virginia prescription monitoring program 2010 statistics. http://www.dhp.virginia.gov/dhp_programs/pmp/docs/ProgramStats/2010PMPStatsDec2010.pdf. Accessed August 20, 2017.

- 24.Li G, Brady JE, Lang BH, Giglio J, Wunsch H, DiMaggio C. Prescription drug monitoring and drug overdose mortality. Inj Epidemiol. 2014;1(1):9. doi: 10.1186/2197-1714-1-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ali MM, Dowd WN, Classen T, Mutter R, Novak SP. Prescription drug monitoring programs, nonmedical use of prescription drugs, and heroin use: evidence from the National Survey of Drug Use and Health. Addict Behav. 2017;69:65-77. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beaudoin FL, Banerjee GN, Mello MJ. State-level and system-level opioid prescribing policies: the impact on provider practices and overdose deaths, a systematic review. J Opioid Manag. 2016;12(2):109-118. doi: 10.5055/jom.2016.0322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leichtling GJ, Irvine JM, Hildebran C, Cohen DJ, Hallvik SE, Deyo RA. Clinicians’ use of prescription drug monitoring programs in clinical practice and decision-making. Pain Med. 2017;18(6):1063-1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin DH, Lucas E, Murimi IB, et al. Physician attitudes and experiences with Maryland’s prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP). Addiction. 2017;112(2):311-319. doi: 10.1111/add.13620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.PDMP Center of Excellence, Brandeis University Briefing on PDMP effectiveness. http://www.pdmpassist.org/pdf/COE_documents/Add_to_TTAC/Briefing%20on%20PDMP%20Effectiveness%203rd%20revision.pdf. Updated September 2014. Accessed August 20, 2017.

- 30.Baehren DF, Marco CA, Droz DE, Sinha S, Callan EM, Akpunonu P. A statewide prescription monitoring program affects emergency department prescribing behaviors. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(1):19-23.e1, e3. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiner SG, Griggs CA, Mitchell PM, et al. Clinician impression versus prescription drug monitoring program criteria in the assessment of drug-seeking behavior in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(4):281-289. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finley EP, Garcia A, Rosen K, McGeary D, Pugh MJ, Potter JS. Evaluating the impact of prescription drug monitoring program implementation: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):420. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2354-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blum CJ, Nelson LS, Hoffman RS. A survey of physicians’ perspectives on the New York State mandatory prescription monitoring program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;70:35-43. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christino MA, Matson AP, Fischer SA, Reinert SE, Digiovanni CW, Fadale PD. Paperwork versus patient care: a nationwide survey of residents’ perceptions of clinical documentation requirements and patient care. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(4):600-604. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00377.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maund E, McDaid C, Rice S, Wright K, Jenkins B, Woolacott N. Paracetamol and selective and non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the reduction in morphine-related side-effects after major surgery: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106(3):292-297. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elia N, Lysakowski C, Tramèr MR. Does multimodal analgesia with acetaminophen, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, or selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and patient-controlled analgesia morphine offer advantages over morphine alone? meta-analyses of randomized trials. Anesthesiology. 2005;103(6):1296-1304. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200512000-00025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ committee on regional anesthesia, executive committee, and administrative council [published correction appears in J Pain. 2016;17(4):508-510]. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131-157. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]