Key Points

Question

Are psychiatric reactions induced by trauma or other life stressors associated with subsequent risk of autoimmune disease?

Findings

In this Swedish register-based retrospective cohort study that included 106 464 patients with stress-related disorders, 1 064 640 matched unexposed individuals, and 126 652 full siblings, exposure to a clinical diagnosis of stress-related disorders was significantly associated with an increased risk of autoimmune disease (incidence rate was 9.1 per 1000 person-years in exposed patients compared with 6.0 and 6.5 per 1000 person-years in matched unexposed individuals and siblings, respectively).

Meaning

Stress-related disorders were significantly associated with risk of subsequent autoimmune disease.

Abstract

Importance

Psychiatric reactions to life stressors are common in the general population and may result in immune dysfunction. Whether such reactions contribute to the risk of autoimmune disease remains unclear.

Objective

To determine whether there is an association between stress-related disorders and subsequent autoimmune disease.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Population- and sibling-matched retrospective cohort study conducted in Sweden from January 1, 1981, to December 31, 2013. The cohort included 106 464 exposed patients with stress-related disorders, with 1 064 640 matched unexposed persons and 126 652 full siblings of these patients.

Exposures

Diagnosis of stress-related disorders, ie, posttraumatic stress disorder, acute stress reaction, adjustment disorder, and other stress reactions.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Stress-related disorder and autoimmune diseases were identified through the National Patient Register. The Cox model was used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs of 41 autoimmune diseases beyond 1 year after the diagnosis of stress-related disorders, controlling for multiple risk factors.

Results

The median age at diagnosis of stress-related disorders was 41 years (interquartile range, 33-50 years) and 40% of the exposed patients were male. During a mean follow-up of 10 years, the incidence rate of autoimmune diseases was 9.1, 6.0, and 6.5 per 1000 person-years among the exposed, matched unexposed, and sibling cohorts, respectively (absolute rate difference, 3.12 [95% CI, 2.99-3.25] and 2.49 [95% CI, 2.23-2.76] per 1000 person-years compared with the population- and sibling-based reference groups, respectively). Compared with the unexposed population, patients with stress-related disorders were at increased risk of autoimmune disease (HR, 1.36 [95% CI, 1.33-1.40]). The HRs for patients with posttraumatic stress disorder were 1.46 (95% CI, 1.32-1.61) for any and 2.29 (95% CI, 1.72-3.04) for multiple (≥3) autoimmune diseases. These associations were consistent in the sibling-based comparison. Relative risk elevations were more pronounced among younger patients (HR, 1.48 [95% CI, 1.42-1.55]; 1.41 [95% CI, 1.33-1.48]; 1.31 [95% CI, 1.24-1.37]; and 1.23 [95% CI, 1.17-1.30] for age at ≤33, 34-41, 42-50, and ≥51 years, respectively; P for interaction < .001). Persistent use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during the first year of posttraumatic stress disorder diagnosis was associated with attenuated relative risk of autoimmune disease (HR, 3.64 [95% CI, 2.00-6.62]; 2.65 [95% CI, 1.57-4.45]; and 1.82 [95% CI, 1.09-3.02] for duration ≤179, 180-319, and ≥320 days, respectively; P for trend = .03).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this Swedish cohort, exposure to a stress-related disorder was significantly associated with increased risk of subsequent autoimmune disease, compared with matched unexposed individuals and with full siblings. Further studies are needed to better understand the underlying mechanisms.

This cohort study uses Swedish national registry data to investigate associations between PTSD, stress reactions, and adjustment disorders and subsequent autoimmune disease.

Introduction

Most humans are at some point during their lives exposed to trauma or significant life stressors, including loss of loved ones and exposure to various disasters or violence.1,2 While many individuals exposed to such adversities gradually recover,1,3 a significant proportion goes on to develop severe psychiatric reactions, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or acute stress reaction (also known as acute stress disorder) after life-threatening events,4 or adjustment disorder triggered by an identifiable and stressful life change.5 Individuals with such stress-related disorders experience an array of physiologic alterations, including disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis6 and autonomic nervous system,6,7 which in turn may influence multiple bodily systems, eg, immune function,6,8 and thereby susceptibility to disease.

Manifested as abnormal immune reaction in specific organs or bodily systems, autoimmune disease may be influenced by psychiatric reactions to life stressors. Although animal data lend support to a potential link,6 epidemiological evidence underpinning the association between stress-related disorders and autoimmune diseases in humans is limited. Existing data are largely based on male, military samples9,10,11 focusing on PTSD instead of all clinically confirmed, stress-related disorders. Further limitations entail cross-sectional designs,10 small sample sizes,9,10,11 and incomplete control of familial factors.9,10 The purpose of this study was to assess the association between stress-related disorders and subsequent risk of autoimmune disease, while controlling for familial factors through a sibling-based comparison, using nationwide registers in Sweden that include information on all medical diagnoses and family links.

Methods

Study Design

Based on the Swedish Population and Housing Census in 1980, we identified all Swedish-born individuals living in Sweden in 1980. These individuals were followed up from January 1, 1981, by cross-linking the census data to the National Patient Register, Multi-Generation Register, Prescribed Drug Register, Cause of Death Register, and Migration Register using the national identification numbers unique for all Swedish inhabitants. The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Review Board in Stockholm; the requirement of informed consent is waived in register-based studies in Sweden.

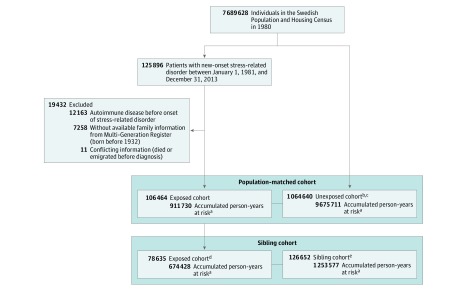

We compiled an exposed cohort of all individuals who received their first diagnosis of a stress-related disorder between January 1, 1981, and December 31, 2013 (Figure 1). We excluded patients with a history of autoimmune disease or with conflicting information. Further, we excluded individuals born prior to 1932 to allow complete identification of family members from the Multi-Generation Register.

Figure 1. Study Design.

Individuals were identified from the Swedish National Inpatient Register (1964-present) and the Swedish National Outpatient Register (2001-present). Those in the population-matched cohort were individually matched 1:10 (by sex and birth year).

aThe first year of follow-up was excluded for calculating the accumulated person-years.

bEligible unexposed individuals were the ones without stress-related disorders and autoimmune diseases at the diagnosis of the index patient. The matching was performed using the density sampling method.

cAmong the unexposed individuals, 15243 (1.4%) received a diagnosis of stress-related disorder during follow-up and contributed to the exposed group after the diagnosis.

dA subgroup of the exposed cohort involved in the population-matched cohort, including only exposed patients with trackable full siblings without stress-related disorders and autoimmune diseases at the diagnosis date of the index patient.

eAmong the full siblings, 5295 (4.2%) received a diagnosis of stress-related disorders during follow-up and contributed to the exposed group after the diagnosis.

Stress-Related Disorders, Comorbidities, and Pharmaceutical Treatment

The Swedish National Patient Register includes nationwide information on inpatient diagnoses since 1987 (>80% of the country during 1981-1986),12 and more than 80% of hospital-based outpatient specialist diagnoses (from both private and public caregivers) since 2001. Primary care is not yet covered by this register. We defined stress-related disorders as any first inpatient or outpatient visit with a primary diagnosis registered in the National Patient Register according to the eighth to 10th revisions of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes 307 and 308.4 (ICD-8); 308 and 309 (ICD-9); and F43 (ICD-10) (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Stress-related disorders were further divided into PTSD (ICD-9: 309B; ICD-10: F43.1), acute stress reaction (ICD-9: 308, 309A; ICD-10: F43.0), and adjustment disorder and other stress reactions (ICD-8: 307 and 308.4; ICD-9: 309X; ICD-10: F43.2, F43.8, and F43.9).

Because PTSD might initially be diagnosed as other stress-related disorders (most likely as acute stress reaction13), we classified all patients receiving a diagnosis of PTSD within 1 year after their first stress-related disorder diagnosis as patients with PTSD. Further, for patients diagnosed as having a stress-related disorder in 2001 onward, we classified the severity of stress-related disorders by the type (ie, inpatient, outpatient, or both) and intensity (ie, duration of inpatient stay and/or frequency of outpatient visits) of psychiatric care during the first year after diagnosis.

Other psychiatric disorders are common comorbidities of stress-related disorders.14,15 We therefore considered other psychiatric diagnoses recorded more than 3 months before the first stress-related disorder diagnosis as “history of other psychiatric disorders,” whereas diagnoses from 3 months before to 1 year after the first diagnosis of stress-related disorder were recorded as “psychiatric comorbidities.” Diagnoses of other psychiatric disorders were similarly obtained from the National Patient Register (ICD-8: 290-319 except 307 and 308.4; ICD-9: 290-319 except 308 and 309; and ICD-10: F10-F99 except for F43).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the recommended first-line pharmacotherapy for PTSD with documented effectiveness for its core symptoms.16 To study the potential role of this treatment on the association of interest, we retrieved information on the dispensing of SSRIs (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical code N06AB) from the Prescribed Drug Register, available from July 2005. We defined SSRI users as individuals who filled 2 or more prescriptions of SSRIs within the first year after diagnosis. The duration of treatment was the number of days between the first and the last dispensation. The average dosage was then calculated by dividing cumulative defined daily dose17 by the duration of treatment.

Population-Matched Unexposed Cohort

We randomly selected 10 persons per exposed patient, individually matched by birth year and sex, from the study base who were free of stress-related disorders and autoimmune diseases at the diagnosis date of the index patient.

Sibling Cohort

Because multiple factors that cluster within families may be associated with both stress-related disorders and autoimmune diseases, we further conducted a sibling-based comparison including both patients with stress-related disorders and their full siblings, ie, with the same biological mother and father.

Follow-up

We followed up all participants from the index date until the first diagnosis of autoimmune disease, death, emigration, or the end of study (December 31, 2013), whichever occurred first. The follow-up of unexposed individuals or siblings was additionally censored if they were later diagnosed as having stress-related disorders. These individuals were then moved to the exposed group. To reduce risks of reverse causality and surveillance bias (ie, increased probability of detecting autoimmune diseases in patients with stress-related disorder due to increased medical surveillance), we excluded the first year of follow-up in all analyses (see flexible parametric survival models in eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

Autoimmune Diseases

Information on autoimmune diseases was retrieved from the National Patient Register. In total, we considered 41 autoimmune diseases,18 using their corresponding ICD codes (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Covariates

Information about education level, family income, and marital status was obtained from the Longitudinal Integration Database for Health Insurance and Labor Market. We calculated Charlson Comorbidity Index score19 for all participants according to the National Patient Register. Family history of autoimmune disease was defined as having any first-degree relatives (biological parents, siblings, or children) with any included autoimmune disease recorded in the National Patient Register. We used the most updated information before the index date for all analyses. Additionally, based on the National Patient Register, we calculated the number of health care visits (including both inpatient stay and outpatient visit, for any reason) for all participants during the first year after study entry, as a proxy of medical surveillance level during follow-up. Because exposed patients received intensive medical care during the first month after their diagnoses, we removed the first month after study entry from this calculation.

Statistical Analysis

We used conditional Cox models to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs of autoimmune diseases in relation to previous stress-related disorders using time after the index date as the underlying time scale.

In the population-matched cohort, we stratified all analyses by matching identifiers (birth year and sex) and adjusted for education level (<9 years, 9-12 years, >12 years, or unknown), family income (top 20%, middle, lowest 20%, or unknown), marital status (single, married/cohabiting, or divorced/widowed), Charlson Comorbidity Index score (0, 1, or ≥2), family history of autoimmune disease (yes or no), and history of other psychiatric disorders (yes or no). We analyzed all stress-related disorders as 1 group followed by separate analyses for PTSD, acute stress reaction, and adjustment disorder and other stress reactions. Also, we separately calculated the HRs for sex, age at index date (by quartiles, ≤33, 34-41, 42-50, or ≥51 years), calendar year at index date (1981-1990, 1991-2000, or 2001-2013), time since index date (1-4 years, 5-9 years, or ≥10 years), family history of autoimmune disease (yes or no), history of other psychiatric disorders (yes or no), and the frequency of health care visits during the first year (0-1 or ≥2 times). We assessed the differences of HRs by introducing an interaction term to the Cox models. Besides the aforementioned relative measures of association, we calculated absolute rate difference with 95% CIs.

We further performed subgroup analyses by psychiatric comorbidity, as well as the type and intensity of psychiatric care received within 1 year after the diagnosis (among patients diagnosed in 2000 onward). For patients diagnosed since July 2005, we examined the potential effect of SSRI use on the association between stress-related disorders and autoimmune disease. The Wald test was used to examine the difference in subgroups (for nominal variables) or to test the potential dose-dependent effect (for ordinal variables).

In addition to a diagnosis of any autoimmune disease, we examined the risk of multiple autoimmune syndromes (ie, having ≥3 autoimmune diseases),20 individual autoimmune diseases (with ≥100 identified cases in the population-matched cohort), as well as 9 major groups of autoimmune diseases (diseases of endocrine, nervous, digestive, skin system, inflammatory arthritis, connective tissue disorders, vasculitis, hematological diseases, and others).

Similar analyses were conducted in the sibling cohort. We used conditional Cox models stratified by family identifier and adjusted for similar variables as in the population-based comparison. HRs between population and sibling analyses were compared using a z test.21

To assess the robustness of the results to the definition of history of other psychiatric disorders, we re-ran the analyses by using a 6-month, instead of 3-month, period prior to stress-related disorder to demark the “history of other psychiatric disorders.” To further address the concern about surveillance bias, we plotted the cumulative incidence curves of autoimmune diseases among participants with more than 5 years of follow-up. Also, we used more stringent definitions of the outcome, including (1) at least 2 health care visits (inpatient stay or outpatient visit) with the same autoimmune disease as a diagnosis and (2) at least 1 inpatient stay with autoimmune disease as the main discharge diagnosis. Furthermore, the frequency of heath care visits during the first year was additionally adjusted as a continuous variable in the Cox models. To further reduce the possibility of reverse causality, we repeated the analyses by excluding the first 2 and 5 years after study entry. All analyses were conducted in SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). A 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Among 7 689 628 Swedish-born individuals, 125 896 patients with their first stress-related disorder diagnosed between 1981 and 2013 were identified. A total of 19 432 persons were excluded according to the exclusion criteria, leaving 106 464 eligible patients for further analyses (Figure 1). Then, 1 064 640 matched unexposed individuals and 126 652 full siblings (of 78 635 exposed patients), who were free of stress-related disorders and autoimmune diseases at the diagnosis date of the index patient, were included as reference groups.

The median age at diagnosis of stress-related disorders was 41 years and 40% of these patients were male (Table 1). Compared with unexposed individuals, exposed patients had a higher Charlson Comorbidity Index score, but lower education level and family income; they were also more likely to be divorced/widowed and have a history of other psychiatric disorders.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Study Cohorts.

| Characteristic | Population-Matched Cohort | Sibling Cohort | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposed Cohort | Matched Unexposed Cohort | Exposed Cohorta | Sibling Cohort | |

| No. of participants | 106 464 | 1 064 640 | 78 635 | 126 652 |

| Follow-up time, mean (SD), y | 9.5 (7.7) | 10.1 (8.0) | 9.5 (7.7) | 10.9 (8.2) |

| Male, % | 40.0 | 40.0 | 40.1 | 51.1 |

| Age at index date, median (IQR), y | 41 (33-50) | 41 (33-50) | 42 (34-50) | 43 (35-52) |

| Age group, No. (%), y | ||||

| ≤33 | 27 717 (26.0) | 277 170 (26.0) | 18 582 (23.6) | 28 337 (22.4) |

| 34-41 | 26 906 (25.3) | 269 060 (25.3) | 20 544 (26.1) | 29 615 (23.4) |

| 42-50 | 26 366 (24.8) | 263 660 (24.8) | 20 694 (26.3) | 33 470 (26.4) |

| ≥51 | 25 475 (23.9) | 254 750 (23.9) | 18 815 (23.9) | 35 230 (27.8) |

| By calendar year at index date, No. (%) | ||||

| 1981-1990 | 13 427 (12.6) | 134 270 (12.6) | 9666 (12.3) | 19 680 (15.5) |

| 1991-2000 | 18 445 (17.3) | 184 450 (17.3) | 13 589 (17.3) | 25 338 (20.0) |

| 2001-2013 | 74 592 (70.1) | 745 920 (71.6) | 55 380 (70.4) | 81 634 (64.5) |

| Education level, No. (%), y | ||||

| <9 | 6016 (5.6) | 58 634 (5.5) | 4286 (5.5) | 11 442 (9.0) |

| 9-12 | 70 230 (66.0) | 633 867 (59.5) | 51 686 (65.7) | 80 881 (63.9) |

| >12 | 27 898 (26.2) | 352 371 (33.1) | 21 315 (27.1) | 31 709 (25.0) |

| Unknown | 2320 (2.2) | 19 768 (1.9) | 1348 (1.7) | 2575 (2.1) |

| Yearly family income level, No. (%) | ||||

| Lowest 20% | 17 944 (16.9) | 139 815 (13.1) | 12 809 (16.3) | 17 028 (13.4) |

| Middle | 58 828 (55.3) | 571 367 (53.7) | 43 840 (55.8) | 65 567 (51.8) |

| Top 20% | 15 902 (14.9) | 215 475 (20.2) | 12 132 (15.4) | 23 963 (18.9) |

| Unknown | 13 790 (13.0) | 137 983 (13.0) | 9854 (12.5) | 20 094 (15.9) |

| Marital status, No. (%) | ||||

| Single | 47 634 (44.7) | 470 508 (44.2) | 34 130 (43.4) | 51 529 (40.7) |

| Married or cohabiting | 40 773 (38.3) | 493 631 (46.4) | 31 018 (39.5) | 60 010 (47.4) |

| Divorced or widowed | 18 057 (17.0) | 100 501 (9.4) | 13 487 (17.2) | 15 113 (11.9) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score, No. (%)b | ||||

| 0 | 84 421 (79.3) | 930 806 (87.4) | 62 485 (79.5) | 107 531 (84.9) |

| 1 | 14 650 (13.8) | 95 007 (8.9) | 10 607 (13.5) | 13 329 (10.5) |

| ≥2 | 7393 (6.9) | 38 827 (3.7) | 5543 (7.0) | 5792 (4.6) |

| History of other psychiatric disorders, No. (%)c | ||||

| Yes | 33 169 (31.2) | 61 578 (5.8) | 25 008 (31.8) | 12 357 (9.8) |

| No | 73 295 (68.8) | 1 003 062 (94.2) | 53 627 (68.2) | 114 295 (90.2) |

| Family history of autoimmune diseases, No. (%) | ||||

| Yes | 25 514 (24.0) | 231 800 (21.8) | 19 063 (24.2) | 31 053 (24.5) |

| No | 80 950 (76.0) | 832 840 (78.2) | 59 572 (75.8) | 95 599 (75.5) |

| No. of health care visits during the first year after study entry, No. (%)d | ||||

| 0-1 times | 60 374 (56.7) | 929 198 (87.3) | 42 658 (54.2) | 107 565 (84.9) |

| ≥2 times | 46 090 (43.3) | 135 442 (12.7) | 35 977 (45.8) | 19 087 (15.1) |

| Type of stress-related disorders, No. (%) | ||||

| Diagnosis type | ||||

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 6607 (6.2) | 4827 (6.1) | ||

| Acute stress reaction | 46 693 (43.9) | 34 299 (43.7) | ||

| Adjustment disorder and other stress reaction | 53 164 (49.9) | 39 509 (50.2) | ||

| Psychiatric comorbiditye | ||||

| Yes | 24 722 (23.2) | 18 937 (24.1) | ||

| No | 81 742 (76.8) | 59 698 (75.9) | ||

| Psychiatric care received during the year after diagnosisf | ||||

| All | 74 592 | 55 380 | ||

| Both inpatient and outpatient | 4186 (5.6) | 3129 (5.7) | ||

| Inpatient only | 13 152 (17.6) | 9644 (17.4) | ||

| Outpatient only | 57 254 (76.8) | 42 607 (76.9) | ||

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

A subgroup of the exposed cohort involved in the population-matched cohort, including only exposed patients with eligible full siblings.

The Charlson Comorbidity Index is an approach of measuring comorbidities burden, with a weight of 1/2/3/6 assigned for each comorbidity category based on the reported risk of mortality or resource use. The sum of all the weights is the comorbidity index for an individual (possible range, 0-33). A score of zero shows no comorbidities; the higher the score, the more likely the predicted outcome will result in mortality or higher medical resource use.

Psychiatric disorders diagnosed before 3 months prior to the index date (ie, the diagnosis date of exposed patients or the diagnosis date of the index patient for matched unexposed individuals and siblings).

Both inpatient and outpatient visits were included. The first month after study entry was removed from this calculation.

Psychiatric disorders (other than stress-related disorders) diagnosed from 3 months before to 1 year after the diagnosis of stress-related disorders.

Only for patients diagnosed in 2001 and onward. Only medical visit with stress-related disorders as main diagnosis was taken into account.

During a mean follow-up of 10 years, we identified 8284 individuals with a newly diagnosed autoimmune disease among exposed patients (incidence rate, 9.1 [95% CI, 8.9-9.3] per 1000 person-years in the population-matched cohort and 9.0 [95% CI, 8.8-9.2] per 1000 person-years in the sibling cohort), 57 711 among matched unexposed individuals (incidence rate, 6.0 [95% CI, 5.9-6.0] per 1000 person-years), and 8151 among the siblings (incidence rate, 6.5 [95% CI, 6.4-6.7] per 1000 person-years). This corresponds to an absolute rate difference of 3.12 (95% CI, 2.99-3.25) and 2.49 (95% CI, 2.23-2.76) per 1000 person-years compared with the population- and sibling-based reference groups, respectively. After controlling for confounders, the risk for autoimmune disease was increased among patients with stress-related disorders (HR, 1.36 [95% CI, 1.33-1.40]; Table 2) compared with matched unexposed individuals. Specifically, the HR was 1.46 (95% CI, 1.32-1.61) for PTSD, 1.35 (95% CI, 1.30-1.40) for acute stress reactions, and 1.37 (95% 1.32-1.41) for adjustment disorder and other stress reactions (Table 2 and eTable2 in the Supplement); there was no statistically significant difference between these HRs (P = .14). The sibling-based comparison corroborated the observed associations, in which lower estimates were noted for adjustment disorder and other stress reactions (HR, 1.27 [95% CI, 1.20-1.34]; P for difference between population- and sibling-based comparison = .03), but not acute stress reaction (HR, 1.31 [95% CI, 1.23-1.40]; P = .42) and PTSD (HR, 1.39 [95% CI, 1.16-1.65]; P = .63) (eTables 3 and 4 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Risk of Autoimmune Disease Among Patients With Any Stress-Related Disorder or Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Compared With Matched Unexposed Individuals.

| Patients With Any Stress-Related Disorder | Patients With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Autoimmune Disease Cases/No. of Accumulated Person-Years × 1000 (Incidence Rate/1000 Person-Years) | Absolute Rate Difference/1000 Person-Years (95% CI) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI)a |

P Valueb |

No. of Autoimmune Disease Cases/No. of Accumulated Person-Years × 1000 (Incidence Rate/1000 Person-Years) | Absolute Rate Difference/1000 Person-Years (95% CI) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI)a |

P Valueb |

|||

| Exposed Patients | Matched Unexposed Individuals | Exposed Patients | Matched Unexposed Individuals | |||||||

| All | 8284/911.7 (9.1) | 57 711/9675.7 (6.0) | 3.12 (2.99-3.25) | 1.36 (1.33-1.40) | 532/50.3 (10.6) | 3412/533.1 (6.4) | 4.18 (4.14-4.21) | 1.46 (1.32-1.61) | ||

| By sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 5746/544.2 (10.6) | 39 620/5702.4 (7.0) | 3.61 (3.50-3.72) | 1.36 (1.32-1.40) | .97 | 404/32.8 (12.3) | 2529/347.4 (7.3) | 5.04 (5.01-5.07) | 1.49 (1.32-1.67) | .50 |

| Male | 2538/367.5 (6.9) | 18 091/3973.3 (4.6) | 2.35 (2.28-2.43) | 1.37 (1.31-1.43) | 128/17.5 (7.3) | 883/185.7 (4.8) | 2.56 (2.54-2.58) | 1.36 (1.12-1.67) | ||

| By age at index date (quartiles), y | ||||||||||

| ≤33 | 2513/353.8 (7.1) | 15 780/3671.0 (4.3) | 2.81 (2.74-2.87) | 1.48 (1.42-1.55) | <.001 | 152/17.0 (9.0) | 788/177.2 (4.5) | 4.52 (4.50-4.53) | 1.82 (1.50-2.20) | .06 |

| 34-41 | 1896/221.0 (8.6) | 12 463/2344.4 (5.3) | 3.26 (3.20-3.33) | 1.41 (1.33-1.48) | 116/12.7 (9.1) | 718/132.8 (5.4) | 3.73 (3.72-3.75) | 1.35 (1.07-1.69) | ||

| 42-50 | 1994/198.8 (10.0) | 14 403/2133.6 (6.8) | 3.28 (3.21-3.35) | 1.31 (1.24-1.37) | 130/12.2 (10.6) | 928/128.3 (7.2) | 3.40 (3.39-3.42) | 1.33 (1.09-1.62) | ||

| ≥51 | 1881/138.2 (13.6) | 15 065/1526.8 (9.9) | 3.74 (3.67-3.81) | 1.23 (1.17-1.30) | 134/8.4 (15.9) | 978/94.8 (10.3) | 5.58 (5.56-5.60) | 1.35 (1.11-1.65) | ||

| By time since index date, y | ||||||||||

| 1 to <5 | 2818/335.5 (8.4) | 17 914/3439.3 (5.2) | 3.19 (3.12-3.26) | 1.41 (1.35-1.47) | .08 | 204/20.0 (10.2) | 1095/205.4 (5.3) | 4.85 (4.83-4.87) | 1.53 (1.29-1.82) | .30 |

| 5 to <10 | 2234/268.7 (8.3) | 15 772/2819.1 (5.6) | 2.72 (2.65-2.79) | 1.33 (1.26-1.39) | 147/14.6 (10.1) | 918/153.7 (6.0) | 4.10 (4.09-4.12) | 1.50 (1.24-1.82) | ||

| ≥10 | 3228/307.0 (10.5) | 24 009/3411.5 (7.0) | 3.48 (3.39-3.56) | 1.36 (1.31-1.41) | 181/15.6 (11.6) | 1399/173.7 (8.1) | 3.52 (3.50-3.54) | 1.35 (1.15-1.60) | ||

| By calendar year at index date | ||||||||||

| 1981-1990 | 2077/288.6 (7.2) | 15 556/3145.6 (5.0) | 2.25 (2.18-2.32) | 1.32 (126-1.42) | .21 | 114/13.4 (8.5) | 801/145.2 (5.5) | 3.01 (2.99-3.02) | 1.44 (1.17-1.78) | .26 |

| 1991-2000 | 2238/251.1 (8.9) | 15782/2687.9 (5.9) | 3.08 (3.01-3.15) | 1.36 (1.29-1.39) | 137/15.1 (9.1) | 1026/162.4 (6.3) | 2.78 (2.76-2.80) | 1.35 (1.12-1.64) | ||

| 2001-2013 | 3969/372.1 (10.7) | 26 373/3842.3 (6.9) | 3.81 (3.72-3.90) | 1.39 (1.34-1.44) | 281/21.9 (12.8) | 1585/225.5 (7.0) | 5.87 (5.85-5.90) | 1.53 (1.32-1.77) | ||

| By history of other psychiatric disordersc | ||||||||||

| Yes | 2690/234.5 (11.5) | 3573/377.5 (9.5) | 2.01 (1.96-2.05) | 1.23 (1.12-1.35) | <.001 | 192/15.8 (12.2) | 235/22.2 (10.6) | 1.57 (1.56-1.58) | 1.25 (0.89-1.77) | .03 |

| No | 5594/677.2 (8.3) | 54 138/9298.2 (5.8) | 2.44 (2.32-2.56) | 1.40 (1.36-1.44) | 340/34.5 (9.9) | 3177/511.0 (6.2) | 3.63 (3.60-3.67) | 1.55 (1.38-1.74) | ||

| By family history of autoimmune diseases among first-degree relatives | ||||||||||

| Yes | 2043/171.6 (11.9) | 13 072/1613.1 (8.1) | 3.80 (3.74-3.87) | 1.36 (1.27-1.46) | .79 | 147/10.6 (13.9) | 836/95.2 (8.8) | 5.06 (5.04-5.08) | 1.86 (1.42-2.44) | .30 |

| No | 6241/751.0 (8.3) | 44 639/7823.6 (5.7) | 2.90 (2.78-3.01) | 1.37 (1.33-1.41) | 385/39.7 (9.7) | 2576/438.0 (5.9) | 3.82 (3.79-3.85) | 1.41 (1.25-1.59) | ||

| By No. of health care visits during the first year after study entryd | ||||||||||

| 0-1 | 4738/611.6 (7.8) | 50 081/8937.5 (5.6) | 2.14 (1.92-2.37) | 1.29 (1.25-1.33) | <.001 | 253/28.5 (8.9) | 2973/490.1 (6.1) | 2.80 (1.69-3.91) | 1.42 (1.24-1.62) | .49 |

| ≥2 | 3546/300.2 (11.8) | 7630/738.2 (10.3) | 1.48 (1.03-1.93) | 1.15 (1.08-1.22) | 279/21.8 (12.8) | 439/43.1 (10.2) | 2.63 (0.85-4.41) | 1.31 (1.06-1.62) | ||

Cox models were stratified by matching identifiers (birth year and sex) and adjusted for education level, family income, marital status, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, family history of autoimmune disease, and history of other psychiatric disorders. The first year of follow-up was excluded for all analyses.

P value was derived from interaction test by incorporating an interaction term to the Cox model.

Psychiatric disorders diagnosed before 3 months prior to the index date (ie, the diagnosis date of exposed patients or the diagnosis date of the index patient for matched unexposed individuals and siblings).

Both inpatient stay and outpatient visit were included. The first month after study entry was removed from this calculation.

These associations did not differ by sex, calendar period, or family history of autoimmune disease (Table 2 and eTables 2-4 in the Supplement), but were stronger among patients exposed at a younger age (HR, 1.48 [95% CI, 1.42-1.55], 1.41 [95% CI, 1.33-1.48], 1.31 [95% CI, 1.24-1.37], and 1.23 [95% CI, 1.17-1.30] for age at ≤33, 34-41, 42-50, and ≥51 years, respectively; P for interaction < .001) or without a history of other psychiatric disorders (HR, 1.23 [95% CI, 1.12-1.35] vs 1.40 [95% CI, 1.36-1.44] for patients with and without such a history, respectively; P for interaction < .001). Furthermore, although the association was modified by the frequency of health care visits (HR, 1.29 [95% CI, 1.25-1.33] for 0-1 vs 1.15 [95% CI, 1.08-1.22] for ≥2 visits; P for interaction < .001), it was present at both levels of medical surveillance.

The presence of psychiatric comorbidity was associated with further elevated risk of autoimmune disease, eg, for all stress-related disorders, the HR was 1.47 (95% CI, 1.40-1.54) and 1.33 (95% CI, 1.29-1.37) for patients with and without psychiatric comorbidity, respectively (P for difference < .001) (Table 3 and eTable 5 in the Supplement). Additionally, for patients with PTSD who initiated SSRI treatment (42.6% of all patients with PTSD), the observed excess risk decreased with persistent use of SSRIs during the first year after PTSD diagnosis (HR, 3.64 [95% CI, 2.00-6.62], 2.65 [95% CI, 1.57-4.45], and 1.82 [95% CI, 1.09-3.02] for duration ≤179, 180-319, and ≥320 days, respectively, irrespective of dosage level; P for trend = .03). However, no such findings were noted for other stress-related disorders.

Table 3. Risk of Autoimmune Disease Among Patients With Any Stress-Related Disorder or Posttraumatic Stress Disorder by Psychiatric Care Indicators Compared With Matched Unexposed Individuals.

| Psychiatric Care Indicators | Patients With Any Stress-Related Disorder | Patients With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Autoimmune Disease Cases/No. of Accumulated Person-Years × 1000 (Incidence Rate/1000 Person-Years) | Absolute Rate Difference/1000 Person-Years (95% CI) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI)a |

P Valueb | No. of Autoimmune Disease Cases/No. of Accumulated Person-Years × 1000 (Incidence Rate/1000 Person-Years) | Absolute Rate Difference/1000 Person-Years (95% CI) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI)a |

P Valueb | |||

| Exposed Patients | Matched Unexposed Individuals | Exposed Patients | Matched Unexposed Individuals | |||||||

| Psychiatric comorbidityc | ||||||||||

| Yes | 2114/262.6 (8.05) | 15 298/2801.3 (5.46) | 2.59 (2.24-2.94) | 1.47 (1.40-1.54) | <.001 | 131/11.1 (11.8) | 752/119.7 (6.3) | 5.53 (3.46-7.60) | 1.89 (1.55-2.29) | .002 |

| No | 6170/649.2 (9.50) | 42 413/6874.5 (6.17) | 3.33 (3.09-3.58) | 1.33 (1.29-1.37) | 401/39.2 (10.2) | 2660/413.4 (6.4) | 3.79 (2.76-4.82) | 1.33 (1.18-1.51) | ||

| Type of psychiatric care (for patients diagnosed after 2000)d | ||||||||||

| Both inpatient and outpatient | 207/17.8 (11.6) | 1271/187.2 (6.8) | 4.83 (3.21-6.46) | 1.43 (1.22-1.68) | .26 | 17/1.3 (13.6) | 95/13.1 (7.3) | 6.35 (-.28-13.0) | 1.84 (0.83-2.86) | .09 |

| Inpatient only | 777/69.5 (11.2) | 5085/737.6 (6.9) | 4.28 (3.47-5.09) | 1.42 (1.31-1.54) | 23/1.7 (13.7) | 119/17.4 (6.8) | 6.87 (1.13-12.6) | 1.80 (1.04-3.11) | ||

| Outpatient only | 2800/267.5 (10.5) | 18 718/2732.9 (6.9) | 3.62 (3.22-4.02) | 1.38 (1.32-1.44) | 237/18.6 (12.8) | 1339/190.9 (7.0) | 5.75 (4.08-7.42) | 1.51 (1.29-1.77) | ||

| Total days of inpatient stay (for patients received any inpatient care, by tertiles)d | ||||||||||

| 1-4 d | 2633/315.3 (8.4) | 18 918/3370.3 (5.6) | 2.74 (2.41-3.07) | 1.33 (1.27-1.39) | .32 | 79/9.4 (8.4) | 567/101.4 (5.6) | 2.82 (0.91-4.73) | 1.27 (0.98-1.64) | .10 |

| 5-12 d | 1353/159.1 (8.5) | 9634/1712.5 (5.6) | 2.88 (2.41-3.35) | 1.37 (1.29-1.46) | 62/7.8 (7.9) | 525/82.7 (6.4) | 1.58 (-.47-3.62) | 1.21 (0.91-1.61) | ||

| >12 d | 1496/169.8 (8.8) | 10 430/1858.4 (5.6) | 3.20 (2.74-3.66) | 1.40 (1.32-1.49) | 154/14.2 (10.6) | 981/158.1 (6.2) | 4.40 (2.68-6.12) | 1.63 (1.35-1.96) | ||

| Frequency of outpatient visits (for patients received outpatient care alone)d | ||||||||||

| <3 times | 2316/223.2 (10.4) | 15 726/2283.1 (6.9) | 3.49 (3.05-3.93) | 1.34 (1.30-1.39) | .11 | 157/12.6 (12.5) | 917/129.9 (7.1) | 5.42 (3.42-7.43) | 1.46 (1.20-1.77) | .63 |

| ≥3 times | 486/44.5 (10.9) | 3003/451.4 (6.7) | 4.28 (3.28-5.28) | 1.45 (1.34-1.58) | 80/6.0 (13.4) | 422/60.990 (6.9) | 6.45 (3.45-9.46) | 1.64 (1.25-2.15) | ||

| Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors within the first year after diagnosise | ||||||||||

| Dose level | ||||||||||

| No medication | 1185/116.5 (10.2) | 8309/1195.5 (7.0) | 3.22 (2.62-3.82) | 1.31 (1.22-1.39) | 83/7.3 (11.4) | 546/75.1(7.2) | 4.09 (1.57-6.61) | 1.25 (0.96-1.62) | ||

| Low dose (≤1.0 DDD/d) | ||||||||||

| ≤179 | 25/3.1 (8.1) | 229/30.970 (7.4) | 0.74 (-2.6-4.07) | 1.08 (0.71-1.64) | .73f | 6/0.2 (32.0) | 16/2.0 (8.0) | 24.0 (-1.9-49.9) | 4.21 (1.40-12.6) | .03f |

| 180-319 | 104/7.4 (14.0) | 510/76.170 (6.7) | 7.27 (4.53-10.0) | 1.98 (1.57-2.51) | 12/0.6 (21.8) | 29/5.7 (5.1) | 16.6 (4.19-29.1) | 3.64 (1.46-9.08) | ||

| ≥320 | 111/7.9 (14.1) | 587/80.740 (7.3) | 6.83 (4.14-9.52) | 1.78 (1.43-2.22) | 8/0.7 (11.4) | 49/7.0 (7.0) | 4.42 (-3.7-12.6) | 1.19 (0.49-2.89) | ||

| High dose (>1.0 DDD/d) | ||||||||||

| ≤179 | 93/6.3 (14.7) | 473/66.440 (7.1) | 7.56 (4.51-10.6) | 1.68 (1.31-2.16) | 11/0.5 (23.9) | 37/4.9 (7.5) | 16.4 (2.05-30.7) | 3.10 (1.28-7.50) | ||

| 180-319 | 168/13.5 (12.5) | 960/137.3 (7.0) | 5.50 (3.56-7.44) | 1.48 (1.23-1.78) | 18/1.2 (15.0) | 80/12.4 (6.5) | 8.56 (1.47-15.6) | 2.38 (1.24-4.57) | ||

| ≥320 | 155/12.0 (12.9) | 879/122.6 (7.2) | 5.73 (3.65-7.82) | 1.74 (1.46-2.07) | 16/1.0 (16.7) | 79/9.8 (8.1) | 8.65 (0.28-17.0) | 1.99 (1.14-3.50) | ||

Abbreviation: DDD, defined daily dose.

Cox models were stratified by matching identifiers (birth year and sex) and adjusted for education level, family income, marital status, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, family history of autoimmune disease, and history of other psychiatric disorders. The first year of follow-up was excluded for all analyses.

For nominal variables (ie, psychiatric comorbidity, type of psychiatric care), P value for subgroup difference was derived from the Wald test. For ordinal variables (ie, total days of inpatient stay, frequency of outpatient visits, and duration of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors use), P value for trend was derived from the Wald test to test the potential dose-response relationship.

Psychiatric disorders (other than stress-related disorders) diagnosed from 3 months before to 1 year after the diagnosis of stress-related disorders.

Psychiatric care (ie, inpatient or outpatient visit with any stress-related disorder as the main diagnosis) received within 1 year after the stress-related disorder diagnosis, according to information from the National Patient Register.

Only for patients diagnosed after July 1, 2005. Dose and duration were calculated according to the records from the Drug Prescription Register. Data shown as duration in days by tertiles.

P value was calculated for different duration groups (≤179, 180-319, and ≥320 days) among drug users, irrespective of dosage level.

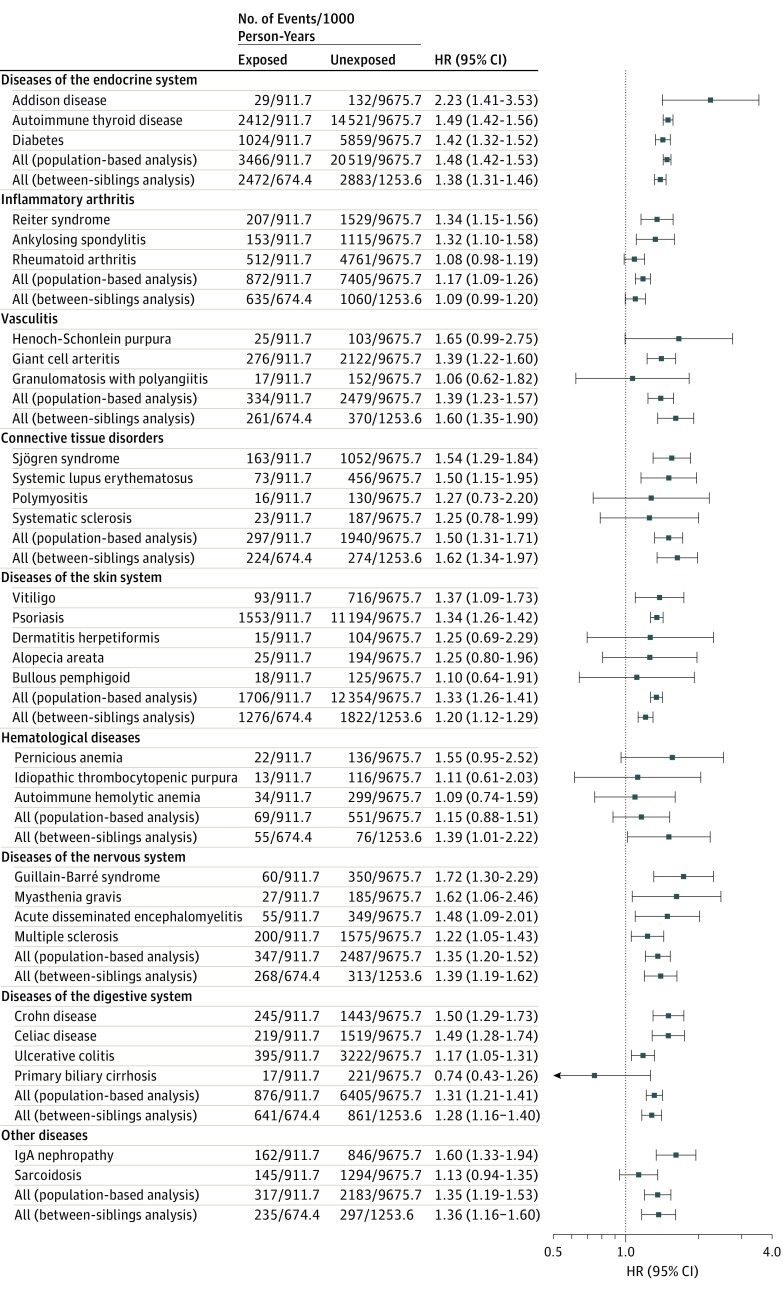

The association of PTSD, but not other stress-related disorders, was stronger for multiple autoimmune syndromes than single autoimmune disease (HR, 1.46 [95% CI, 1.32-1.61] and 2.29 [95% CI, 1.72-3.04] for any and ≥3 autoimmune diseases, respectively; P for difference < .001; eFigure 2 in the Supplement). Except for hematological disorders, which only showed a risk elevation in the sibling-based comparison, stress-related disorders were associated with elevated risks of all major groups of autoimmune diseases in both the population-matched and sibling cohorts (Figure 2). Statistically significant associations were noted between stress-related disorders and 18 individual autoimmune diseases, eg, Addison disease (HR, 2.23 [95% CI, 1.41-3.35]), Guillain-Barré syndrome (HR, 1.72 [95% CI, 1.30-2.29]), and IgA nephropathy (HR, 1.60 [95% CI, 1.33-1.94]).

Figure 2. Risk Estimates of Association Between Stress-Related Disorders and Different Types of Autoimmune Diseases.

For analysis of the population-matched cohort, autoimmune diseases with less than 100 observed cases were not analyzed separately, but they contributed to the calculations of hazard ratios (HRs) for corresponding main categories. For analysis of the sibling cohort, due to the limited data power, we only provided estimates for autoimmune diseases by main categories. For analysis of the population-matched cohort, Cox models were stratified by matching identifiers (birth year and sex) and adjusted for education level, family income, marital status, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, family history of autoimmune disease, and history of other psychiatric disorders. For analysis of the sibling cohort, Cox models were stratified by family identifiers and adjusted for age at the index date, sex, education level, family income, marital status, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, and history of other psychiatric disorders. The first year of follow-up was excluded for all analyses.

Restricting to participants with more than 5 years of follow-up, patients with stress-related disorders had a higher cumulative incidence of autoimmune diseases compared with their matched unexposed individuals across the follow-up period (eFigure 3 in the Supplement). Additional adjustment for medical surveillance level yielded somewhat lower point estimates (eTable 6 in the Supplement) while changing the definitions for history of other psychiatric disorders and autoimmune disease, and the extension of the lag-time period yielded similar results (eTables 7 and 8 in the Supplement).

Discussion

Based on the nationwide population- and sibling-based comparisons, individuals who developed stress-related disorders after traumatic or other stressful events were at elevated risk of developing autoimmune disease. These associations were independent of history of other psychiatric disorders and became stronger with the presence of co-occurring psychiatric comorbidities. In addition, among patients with PTSD specifically, persistent use of SSRIs throughout the first year after diagnosis was associated with attenuated risk of autoimmune disease.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to address all stress-related disorders and their associations with 41 distinct autoimmune diseases in men and women using both population- and sibling-based comparisons. The observed risk elevations showed heterogeneity for individual autoimmune diseases (eg, HR, 1.09 for rheumatoid arthritis but 1.49 for autoimmune thyroid disease), perhaps due to the differences in pathogenicity or the degree of autoimmunity between diverse autoimmune diseases.22 These findings gain support from previous studies of male Vietnam War veterans10,11 linking self-reported symptoms of PTSD to higher prevalence of a few selected autoimmune diseases. These studies are exclusively based on male samples and their cross-sectional designs limit inferences on causality. Yet, a recent prospective cohort study of US veterans also provided supportive evidence for the association between PTSD and a few types of autoimmune diseases9 while the trauma exposure of these men (ie, war/combat) differed significantly from the general population.

Findings from the present study demonstrated that not only patients with PTSD, but also individuals with other and more common stress-related disorders, experienced considerably increased relative risk of autoimmune disease. Although the present findings are of etiologic importance, the relatively modest differences in incidence rates of autoimmune disease between the exposed and unexposed individuals (9.1 and 6.0 per 1000 person-years, respectively) do not provide direct evidence for altered clinical management or monitoring of persons with stress-related disorders.

The findings of this study are consistent with some biological evidence linking psychological stress and stressful events to varying impairments of immune function,6,8 both of which lend support to a biopsychosocial model in the etiology of autoimmune disease.23 Under stress, the activated autonomic nervous system might induce the dysregulation of immune function and disinhibition of inflammatory response via the inflammatory reflex.24 Moreover, patients with PTSD have been reported to have excessively low cortisol levels,8,25 particularly in the context of early life trauma exposure.26 The consequence of long-lasting lower cortisol levels may be amplified production of proinflammatory cytokines24,25 with accelerated immune cell aging27 and overactivated immune system.28 This pattern is in line with the findings that patients with PTSD were at an increased risk of developing autoimmune disease, especially multiple autoimmune syndromes, with stronger association in younger age groups. An alternative mechanism is a potential change in lifestyle6 after trauma exposure, such as sleep disruption, alcohol or substance abuse, and increased smoking, which may indirectly alter the risk of autoimmune disease.29,30 A weaker association was observed for adjustment disorder and other stress-related reactions in the between-sibling comparison, compared with the population-based comparison, motivating further studies exploring potential genetic and early environmental contributors to the association.

Study strengths include the application of population-based cohort design: a complete follow-up of more than 100 000 patients diagnosed as having stress-related disorders during a 30-year period and a full-sibling comparison to address potential familial confounding. Furthermore, the large sample size provided sufficient statistical power to perform detailed subgroup analyses, including testing for the role of SSRI treatment. In addition, the availability of rich sociodemographic and medical information enabled considerations of a wide range of important confounding factors

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, surveillance bias is a concern in the study. Multiple sensitivity analyses, including using extended lag times and different strategies for outcome ascertainment, restricting the analyses to severe autoimmune diseases, and adjusting for estimated medical surveillance level, suggested some but limited influence of surveillance bias in the reported associations. Second, diagnoses from primary care are not included in the Swedish Nation Patient Register, which may result in lower detection of stress-related disorders and autoimmune diseases, particularly of less-severe conditions. Also, no corroboration exists for the diagnoses of stress-related disorders in the Swedish National Patient Register and diagnostic practices of stress-related disorders have varied over time. PTSD was introduced in ICD-9; thus, patients with PTSD were previously either not diagnosed or diagnosed as having other stress-related disorders. Third, it is challenging to distinguish co-occurring other psychiatric disorders from the pre-existing ones using register data. This concern was partially relieved in sensitivity analysis with altered definitions revealing similar results. Fourth, there was limited information about potential causal pathways linking stress-related disorders to autoimmune diseases. The potential role of other unmeasured factors (eg, infections preceding autoimmune diseases,31 alterations in health-related behavior, or the use of other medications) need to be addressed in future studies. Fifth, despite showing stronger associations among younger participants, the present study had limited statistical power to assess the association between stress-related disorder and autoimmune disease in early life.

Conclusions

In this Swedish cohort, exposure to a stress-related disorder was significantly associated with increased risk of subsequent autoimmune disease, compared with matched unexposed individuals and with full siblings. Further studies are needed to better understand the underlying mechanisms.

eTable 1. International Classification of Diseases (ICD) Codes for Exposure and Outcome Identification

eTable 2. Risk of Autoimmune Disease Among Patients With Acute Stress Reaction or Adjustment Disorder and Other Stress Reactions, Compared With Matched Unexposed Individuals

eTable 3. Risk of Autoimmune Disease Among Patients With Any Stress-Related Disorder or Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Compared With Full Siblings

eTable 4. Risk of Autoimmune Disease Among Patients With Acute Stress Reaction or Adjustment Disorder and Other Stress Reactions, Compared With Full Siblings

eTable 5. Risk of Autoimmune Disease Among Patients With Acute Stress Reaction or Adjustment Disorder and Other Stress Reactions by Psychiatric Care Indicators, Compared With Matched Unexposed Individuals

eTable 6. Association of Stress-Related Disorders With Subsequent Autoimmune Disease, Additionally Adjusted for the Number of Health Care Visits During the First Year After Study Entry, Analysis of the Population-Matched Cohort

eTable 7. Association of Stress-Related Disorders With Subsequent Autoimmune Disease, Using Altered Definition for History of Other Psychiatric Disorders (One of Covariates) and Autoimmune Disease (Outcome), Analysis of the Population-Matched Cohort

eTable 8. Association of Stress-Related Disorders With Subsequent Autoimmune Disease, Using Different Lag-Time, Analysis of the Population-Matched Cohort

eFigure 1. Hazard Ratios of Autoimmune Disease Within the First Year of Study Entry, Analysis of the Population-Matched Cohort

eFigure 2. Associations Between Stress-Related Disorders and Multiple Autoimmune Syndrome (MAS), Analysis of the Population-Matched Cohort

eFigure 3. Cumulative Incidence Rates of Autoimmune Disease Among Patients With Stress-Related Disorder (Exposed Group) and Their Matched Unexposed Individuals (Unexposed Group)

References

- 1.de Vries GJ, Olff M. The lifetime prevalence of traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder in the Netherlands. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22(4):259-267. doi: 10.1002/jts.20429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, et al. Trauma and PTSD in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2017;8(sup5):1353383. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1353383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frans O, Rimmö PA, Aberg L, Fredrikson M. Trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder in the general population. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;111(4):291-299. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00463.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnberg FK, Gudmundsdóttir R, Butwicka A, et al. Psychiatric disorders and suicide attempts in Swedish survivors of the 2004 southeast Asia tsunami: a 5 year matched cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(9):817-824. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00124-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Stress-induced immune dysfunction: implications for health. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(3):243-251. doi: 10.1038/nri1571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blechert J, Michael T, Grossman P, Lajtman M, Wilhelm FH. Autonomic and respiratory characteristics of posttraumatic stress disorder and panic disorder. Psychosom Med. 2007;69(9):935-943. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815a8f6b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Segerstrom SC, Miller GE. Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(4):601-630. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Donovan A, Cohen BE, Seal KH, et al. Elevated risk for autoimmune disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77(4):365-374. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boscarino JA. Posttraumatic stress disorder and physical illness: results from clinical and epidemiologic studies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1032:141-153. doi: 10.1196/annals.1314.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boscarino JA, Forsberg CW, Goldberg J. A twin study of the association between PTSD symptoms and rheumatoid arthritis. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(5):481-486. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d9a80c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:450. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harvey AG, Bryant RA. The relationship between acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: a 2-year prospective evaluation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(6):985-988. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.67.6.985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carta MG, Balestrieri M, Murru A, Hardoy MC. Adjustment disorder: epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2009;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-5-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gros DF, Price M, Magruder KM, Frueh BC. Symptom overlap in posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression. Psychiatry Res. 2012;196(2-3):267-270. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.10.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ursano RJ, Bell C, Eth S, et al. ; Work Group on ASD and PTSD; Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines . Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(11)(suppl):3-31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO Collaborating Center for Drug Statistics Methodology ATC/DDD index 2018. https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/. Accessed March 1, 2018.

- 18.Fang F, Sveinsson O, Thormar G, et al. The autoimmune spectrum of myasthenia gravis: a Swedish population-based study. J Intern Med. 2015;277(5):594-604. doi: 10.1111/joim.12310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Latif S, Jamal A, Memon I, Yasmeen S, Tresa V, Shaikh S. Multiple autoimmune syndrome: Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, coeliac disease and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). J Pak Med Assoc. 2010;60(10):863-865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altman DG, Bland JM. Interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates. BMJ. 2003;326(7382):219. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7382.219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richard-Miceli C, Criswell LA. Emerging patterns of genetic overlap across autoimmune disorders. Genome Med. 2012;4(1):6. doi: 10.1186/gm305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129-136. doi: 10.1126/science.847460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ. The vagus nerve and the inflammatory reflex: linking immunity and metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(12):743-754. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2012.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yehuda R, Teicher MH, Levengood RA, Trestman RL, Siever LJ. Circadian regulation of basal cortisol levels in posttraumatic stress disorder. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;746:378-380. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb39260.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meewisse ML, Reitsma JB, de Vries GJ, Gersons BP, Olff M. Cortisol and post-traumatic stress disorder in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:387-392. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.024877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malan S, Hemmings S, Kidd M, Martin L, Seedat S. Investigation of telomere length and psychological stress in rape victims. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(12):1081-1085. doi: 10.1002/da.20903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gill JM, Saligan L, Woods S, Page G. PTSD is associated with an excess of inflammatory immune activities. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2009;45(4):262-277. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2009.00229.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ascherio A, Munger KL. Environmental risk factors for multiple sclerosis, part II: noninfectious factors. Ann Neurol. 2007;61(6):504-513. doi: 10.1002/ana.21141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palma BD, Gabriel A Jr, Colugnati FA, Tufik S. Effects of sleep deprivation on the development of autoimmune disease in an experimental model of systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291(5):R1527-R1532. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00186.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nyati KK, Nyati R. Role of Campylobacter jejuni infection in the pathogenesis of Guillain-Barré syndrome: an update. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:852195. doi: 10.1155/2013/852195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. International Classification of Diseases (ICD) Codes for Exposure and Outcome Identification

eTable 2. Risk of Autoimmune Disease Among Patients With Acute Stress Reaction or Adjustment Disorder and Other Stress Reactions, Compared With Matched Unexposed Individuals

eTable 3. Risk of Autoimmune Disease Among Patients With Any Stress-Related Disorder or Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Compared With Full Siblings

eTable 4. Risk of Autoimmune Disease Among Patients With Acute Stress Reaction or Adjustment Disorder and Other Stress Reactions, Compared With Full Siblings

eTable 5. Risk of Autoimmune Disease Among Patients With Acute Stress Reaction or Adjustment Disorder and Other Stress Reactions by Psychiatric Care Indicators, Compared With Matched Unexposed Individuals

eTable 6. Association of Stress-Related Disorders With Subsequent Autoimmune Disease, Additionally Adjusted for the Number of Health Care Visits During the First Year After Study Entry, Analysis of the Population-Matched Cohort

eTable 7. Association of Stress-Related Disorders With Subsequent Autoimmune Disease, Using Altered Definition for History of Other Psychiatric Disorders (One of Covariates) and Autoimmune Disease (Outcome), Analysis of the Population-Matched Cohort

eTable 8. Association of Stress-Related Disorders With Subsequent Autoimmune Disease, Using Different Lag-Time, Analysis of the Population-Matched Cohort

eFigure 1. Hazard Ratios of Autoimmune Disease Within the First Year of Study Entry, Analysis of the Population-Matched Cohort

eFigure 2. Associations Between Stress-Related Disorders and Multiple Autoimmune Syndrome (MAS), Analysis of the Population-Matched Cohort

eFigure 3. Cumulative Incidence Rates of Autoimmune Disease Among Patients With Stress-Related Disorder (Exposed Group) and Their Matched Unexposed Individuals (Unexposed Group)