Abstract

There is a new knowledge for clinical presentations and findings of imagine in patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH) in recent more than ten years. According to clinical data in Chinese huge patients with ONFH, the guideline for diagnosis and treatment of ONFH has been put forward by Chinese specialists. The newer contents of guideline include the definition for predisposing risk factors of ONFH, the new knowledge for clinical manifestations, the new interpretation for changes of imagine, important differential diagnosis. Based on the supplementary and revision for widely used staging and classification system, the new Chinese staging and classification system have been established. The advantages of Chinese staging and classification system accord with clinical and pathological features, it could be predicted the prognosis, and clinical applications are convenient. The guideline gives a brief account of principles for treatment selection and treatment methods for enhancement of diagnosis and treatment for ONFH.

Keywords: Osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH), Predisposing risk factors, Diagnosis, Treatment, Guideline

Introduction

Osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH), also known as avascular necrosis, is a common and refractory orthopaedic disease. Because the pathogenesis of nontraumatic ONFH has not been fully elucidated, it is impossible to prevent this disorder. However, international experts have reached a consensus on the main aspects of diagnosis and treatment and issued recommendations (2007) and a Consensus Document (2012) that now play important roles in the standardization of diagnosis and treatment of ONFH1, 2, 3, 4, 5. To standardize treatment techniques, improve efficacy and rationalize use of medical resources, the Joint Surgery Group of the Orthopaedic Branch of the Chinese Medical Association called the domestic osteonecrosis experts together to discuss and develop a “Guideline for Diagnostic and Treatment of Osteonecrosis of the Femoral Head” with the aim of providing a standard for clinicians.

With further study and accumulation of clinical experience, this “guideline” will be revised in a timely manner. These protocols are not mandatory, have no legal standing and cannot be used as a legal basis for resolving medical disputes.

Scope and Target Users

These guidelines are intended to provide concise, patient‐focused, up to date, evidence‐based, expert consensus recommendations for the management of ONFH that are relevant globally. They have been developed to assist physicians and allied health care professionals who deal with patients with ONFH in both primary and secondary (specialist) care settings and should also provide a helpful resource for patients with ONFH, patient representative groups and health care funders and administrators. It is anticipated that these Chinese recommendations for ONFH will be modified and adapted as appropriate for national and regional use.

Definition

There are two categories of ONFH: traumatic and non‐traumatic. ONFH refers to a series of pathological and clinical manifestations that arise from damage to or interruption of the blood supply of the femoral head that result in necrosis of bone marrow cells and osteocytes, the subsequent repair that begins immediately and the associated structural changes, which may be as extreme as collapse of the femoral head1, 2, 6.

It is preferable to try to preserve patients' own joints, especially in younger patients. The most joint‐preserving treatment methods have the highest success rates when they are used to treat early stage, precollapse disease.

Factors Predisposing to ONFH

Factors that predispose subjects to ONFH include hip trauma, including femoral neck and acetabular fractures, hip dislocation, sprain or contusion (no fracture but sometimes intra‐articular hematoma)7; long‐term high‐dose glucocorticoids8, 9, 10, 11; long‐term heavy consumption of alcohol12; thrombophilia and hypofibrinolysis and autoimmune diseases treated with glucocorticoids13, 14, 15; and a history of having used decompression chambers16.

Diagnosis of ONFH

Clinical Manifestations (Chinese Staging System) (Table 1)

Table 1.

ONFH: Chinese staging

| Stage | Clinical findings | Radiographic signs | Pathological changes |

|---|---|---|---|

|

I (pre‐clinical, no‐collapse) According to size of necrotic areaa Ia, small <15% Ib, medium 15%–30% Ic, large >30% |

No |

MRI (+) Bone scan (+) X‐ray (−) CT (−) |

Necrosis of bone marrow Necrosis of osteocytes |

|

II (early stage, no‐collapse) According to size of necrotic areaa IIa, small <15% IIb, medium 15%–30% IIc, large >30% |

No or slight pain |

MRI (+) X‐ray (±) CT (+) |

Necrotic area absorbed Bone repair |

|

III (medium stage pre‐collapse) According to length of crescentb

III a, small <15% III b, medium 15%–30% III c, large >30% |

Onset of pain Slight claudication Moderate pain Limited internal rotation Pain in internal rotation |

Bone marrow edemad (MRI T2WI), subchondral fracture (CT), femoral head contour interrupted (plain X‐ray film), crescent sign |

Subchondral fracture or fracture through necrotic bone |

|

IV (middle‐late stage, collapse) According to depth of collapsec IVa, slight <2 mm IVb, medium 2–4 mm IVc, severe >4 mm |

Moderate to severe pain Claudication Limited internal rotation Aggravated pain when strenuous internal rotation, Limited abduction and adduction |

Femoral head collapse with normal joint space (X‐ray film) | Femoral head collapse |

| V (late‐stage, osteoarthritis) |

Severe pain Severe claudication Limited range of motion |

Flattening of femoral head Narrow joint space (X‐ray film) Acetabular cystic changes or sclerosis |

Cartilage involvede

Osteoarthritis |

, estimation of necrotic area: necrotic area should be estimated in stages I and II on a mid‐coronal section of the femoral head on MRI or CT (small <15%, medium 15%–30%, large >30%), the volume of the necrotic area being estimated through the involved layers37, 38.

, risk of collapse should be estimated in stage III according to length of crescent on AP and frog‐lateral views. Small <15%, medium 15%–30%, large >30%.

, extent of collapse should be estimated in stage IV according to the depth of articular surface collapse in necrotic area by AP and frog‐lateral views X‐ray. Slight <2 mm, medium 2–4 mm, severe >4 mm.

, when X‐ray films show no‐collapse, patients with painful hips need to undergo MRI and CT examination. Necrosis has progressed to collapse (stage III) if bone marrow edema or subchondral fracture have occurred25.

, when collapse has occurred and patients have experienced pain for more than 6 month, articular cartilage will have clearly degenerated (stage V)25.

Stage I. Preclinical stage: no symptoms and signs.

Stage II. Early stage: no or mild hip symptoms, including groin and greater trochanter discomfort, hip pain that occurs during strenuous internal rotation, joint mobility not limited.

Stage III. Pre‐collapse or mid‐term stage: severe hip pain, limping, limited internal rotation, pain increased by strenuous internal rotation.

Stage IV. Collapse or mid‐ and end‐stage: moderate to severe pain, significant limping, flexion, internal rotation and abduction moderately limited.

Stage V. Osteoarthritis or end‐stage stage: moderate or severe pain, severe limping, joint activity was obviously limited (flexion, adduction, internal rotation), joint deformity (flexion and external rotation, adduction)17, 18, 19.

Diagnostic Procedures

Ascertaining the history and clinical symptoms and signs is primary to making a diagnosis; the following auxiliary investigations are recommended20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26:

X‐ray Films

Anteroposterior and frog‐leg lateral views of the hip are recommended. Identification of the crescent sign, which denotes necrosis surrounded by sclerotic bone and segmental collapse, is diagnostic of ONFH. X‐ray films can rule out osteoarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, hip dysplasia and rheumatoid arthritis.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The gold standard for diagnosing ONFH is MRI27. Its specificity and sensitivity are greater than 99%, the recommended sequence being T1WI, T2WI and fat suppression T2WI, coronal and axial scanning. Typical findings are as follows: T1WI, band‐like low signals surrounding fat (medium or high signals) or necrotic bone (medium signals); T2WI, double line sign; T1WI, band‐like low signals; and T2WI with fat suppression, hyperintense lesion edge band. T2WI with fat suppression showing bone marrow edema and joint effusion (I–III) is evidence that the disease has progressed to the pre‐collapse or subsidence stage.

CT Scanning

Although CT scanning cannot directly identify the stage of ONFH, it can clearly show subchondral bone plate fractures, necrosis and extent of repair; coronal and axial two‐dimensional reconstruction CT is recommended28.

Scintigraphy

Scintigraphy can provide clues to diagnosing stage I with high sensitivity and lower specificity. “Cold in hot” imaging is suspicious of ONFH, but requires confirmation by MRI.

Femoral Digital Subtraction Angiography

This invasive procedure is not recommended as a routine investigation.

Histopathological Examination

Obtaining a specimen for histological examination is invasive procedure and only recommended for confirming the diagnosis during core decompression and joint replacement20, 26, 27, 28. The diagnostic criteria for ONFH are as follows: more than 50% of osteocyte lacunae empty within the trabecula with involvement of the adjacent trabeculae and bone marrow.

Diagnostic Criteria

The diagnostic criteria include risk factors and clinical signs and symptoms. ONFH can be diagnosed if one or more of the following criteria are met.

X‐ray Films

Diagnostic features include necrotic foci surrounded by sclerotic bone, segmental collapse, crescent sign and femoral head collapse with preservation of the joint space.

MRI

Diagnostic features include the following: T1WI, band‐like low signals; T2WI, double line sign; and T2WI with fat suppression, necrosis surrounded by high‐band signals or bone marrow edema with band‐like low signals.

CT

Diagnostic features include clearly demarcated necrosis and subchondral fractures.

Diagnosis in the Preclinical Phase (Stage I)

Whether or not they have clinical signs and symptoms, it is recommended that MRI be performed on high‐risk of patients, such as those within 3–12 months after hip trauma and those receiving high doses of glucocorticoids15, 17, 18, 19, 29. For patients with histories hypercoagulable or hypofibrinolytic conditions and subjects who have undergone decompression, MRI is recommended at the time of first presentation. If the MRI is negative, a repeat MRI examination after six months is necessary. If ONFH has been identified in one hip, MRI should be performed on both sides. There are no established guidelines for early diagnosis of ONFH in heavy drinkers.

Diagnosis of Bone Infarction

This is based on changes in the metaphyseal or diaphyseal regions of long bone or bone marrow on MRI mapping; bone calcification or ossification may be visible on CT and X‐ray films in the later stages27.

Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of typical ONFH is not difficult; however, it must be distinguished from the following diseases.

Painful Hip Diseases with Bone Marrow Edema in the Femoral Head and Neck on MRI

Bone marrow edema syndrome was previously known as transient osteoporosis. Its pathogenesis is still unknown. The main points of identification are that only one hip is involved in more than 90% of cases and MRI shows no band‐like low signal changes on T1WI and homogenous high signals on T2WI with fat suppression ranging from the neck to the trochanter of the femoral head, whereas MRI shows band‐like low signal changes on T1WI and inhomogeneous high signals on T2WI with fat suppression in ONFH. Bone marrow edema syndrome can resolve spontaneously 3–12 months after onset or with treatment30, 31.

Osteochondrosis lesion was previously known as osteochondritis dissecans. It often occurs in teenagers or young persons and is characterized by a history of hip impingement and unilateral hip involvement. MRI shows no band‐like low signal changes in the femoral head on T1WI and CT scans show osteochondral fragments with sclerotic edges that are easy to differentiate from ONFH.

Subchondral insufficient fracture is common in older women with osteoporosis and is characterized by absence of a trauma history, sudden onset of unilateral hip pain and restricted joint movement. MRI shows subchondral low signals on T1WI and variable high signals on T2 fat‐suppression images; this is difficult to differentiate from ONFH.

Isolated tumors, the commonest being chondroblastoma, which is benign, can occur in the femoral head. MRI shows subchondral low signals and flaky high signals on T2WI and no band‐like low signals on T1WI and CT scans show irregular osteolytic destruction that is easy to differentiate from ONFH. Malignant tumors, such as low grade central osteosarcoma, are sometimes difficult to identify and need to be differentiated carefully.

Hip Diseases Originating in Cartilage

Idiopathic osteoarthritis in young and middle‐aged subjects is easily confused with ONFH, especially before narrowing of the joint space has developed. The key point of differentiation is that there is no obvious cause of ONFH in these patients. MRI shows no band‐like low signals on T1WI but low signals at the center of femoral articular surface and CT scan shows cystic changes in subchondral bone that are easy to differentiate from ONFH19, 20, 30.

It is not difficult to differentiate osteoarthritis secondary to acetabular dysplasia from ONFH because it has characteristic radiographic findings, including a shallow acetabulum that incompletely contains the femoral head, narrow joint space and secondary osteoarthritis.

Ankylosing spondylitis‐related hip arthritis is common in young male patients and is characterized by bilateral sacroiliac joint involvement, HLA‐B27 (+) and a narrowed or absent joint space with a femoral head that is still round.

Rheumatoid arthritis involves multiple joints throughout the body. When it involves the hip, CT scans clearly show a narrowed joint space, acetabular erosion and subchondral erosion of the femoral head.

Synovial Diseases of the Hip

Early stage pigmented villonodular synovitis is often misdiagnosed as ONFH. MRI shows extensive low signals on T1WI and CT scanning and radiography show cortical erosion of the femoral head and acetabulum.

Synovial osteochondromatosis is common in young people and is characteristically associated with locking of the joint. MRI shows extensive low signals on T1WI, synovial edema and joint effusion with several low signals on T2 fat‐suppression images. CT scans clearly show calcified free bodies in the joint.

Staging of ONFH

Once ONFH has been diagnosed, staging should be undertaken. The aim of staging is to enable selection of an appropriate treatment plan, accurate assessment of the prognosis and evaluation of the effects of treatment. Various valuable staging systems have been published; these include the Ficat, Association Research Circulation Osseous (ARCO), Pennsylvania, Marcus staging and Japan Investigation Committee staging systems32, 33, 34, 35, 36. Based on our clinical practice in recent years, we have established a Chinese staging based on the Pennsylvania staging system (Table 1).

Classification

Classification, which is based on the sites of necrotic foci in the femoral head, is very useful for accurately assessing the prognosis and selecting an appropriate treatment plan. Classification is crucial for all patients for whom joint preservation procedures are planned. There are two types of classification: the Japan Investigation Committee and China‐Japan Friendship Hospital (CJFH) types; we recommend the CJFH type36, 39, 40.

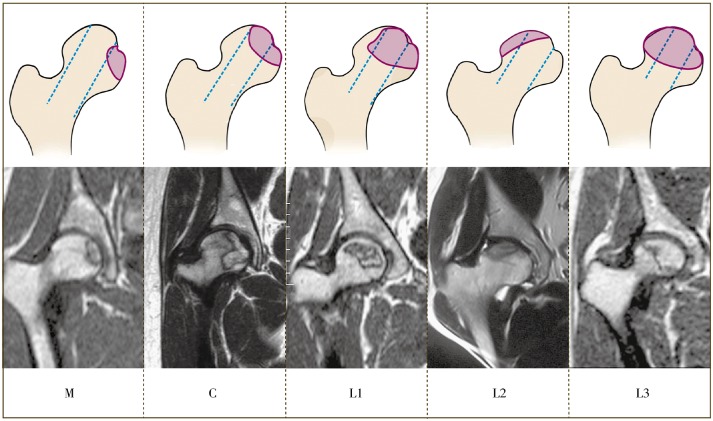

The CJFH classification is based on the locations of necrotic foci in the three pillars of the femoral head. In Type M necrosis involves the medial pillar, in Type C the medial and central pillars, in Type L1 all three pillars with partial preservation of the lateral pillar, in Type L2 the entire lateral pillar and part of the central pillar, and in Type L3 all three pillars, including the cortical bone and marrow (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation (top) and magnetic resonance images (bottom) of the China‐Japan Friendship Hospital classification of osteonecrosis of the femoral head based on the three pillars.

Treatment of ONFH

There are many means of treating for ONFH and they have different outcomes, therefore individualized selection of an appropriate treatment strategy for each patient is necessary. There are three types of treatment methods for ONFH, each with its own indications.

Non‐surgical Treatment

Weight Bearing with Protection and Avoidance of Collision and Combat Sports

For patients in the early or middle stages, weight bearing with crutches is recommended to reduce pain, whereas use of a wheelchair is not recommended.

Drug Treatment, including Chinese and Western Medicine Treatments

Western Medicine: Drugs such as anticoagulants (low molecular weight heparin), fibrinolysis promoters and vasodilators are suitable patients in the pre‐collapse stage of ONFH. Drugs for inhibiting osteoclasts and increasing osteogenesis, such as phosphate preparations, may also be indicated41, 42, 43. Depending on the severity of necrosis, these drugs can be used alone or in combination with with joint‐preservation surgery.

Traditional Chinese medicine 44, 45: The prevention and treatment of ONFH with traditional Chinese medicines emphasizes early diagnosis and treatment, systemic regulation, and differentiation of signs. The basic treatment aims at activating blood and dissolving stasis and is supplemented by methods of activating meridians to reduce pain, stimulate the kidneys to invigorate bone, invigorating the spleen to eliminate damp and so on. The specific treatment is selected according to the syndrome identified. Chinese medicines such as Epimedium (yin yang huo) and pigeon pea leaf (Cajunus Cajun) are currently used in clinical practice. These are also suitable for patients in whom there is no collapse and no syndrome, or with a syndrome but no lateral femoral head involvement. Chinese medicine can improve the effects of joint‐preservation surgery when used in conjunction with it.

Physical Therapy

Forms of physical therapy include extracorporeal shock waves46, high‐frequency magnetic field therapy, hyperbaric oxygen chamber and so on.

Joint‐Preservation Surgery

Joint‐preservation surgery includes core decompression of the femoral head, sometimes in combination with autologous bone marrow cell transplantation, auto‐bone grafting procedures with vascularized muscle pedicle or vascular anastomosis or non‐vascularized autologous bone grafting procedures, and osteotomy.

Core decompression surgery1, 47 can relieve pain; it is recommended that a 3 mm diameter drill be used to produce multiple holes in the femoral head.

Autologous bone marrow cell transplantation involves extracting more than 200 mL of iliac bone marrow blood, isolating mononuclear cells in vitro (without medium), and simply injecting them or implanting them with a carrier48, 49. It is currently in a test phase should be used with caution.

Auto‐bone grafting procedures can involve the use of vascularized muscle pedicle, vascular anastomosis or non‐vascularized autologous bone grafting procedures50, 51, 52.

Vascular free fibular grafts are effective but the procedure is difficult1, 53, 54, 55.

Vascularized bone grafts include deep iliac and superficial iliac vein grafts, the lateral femoral circumflex branch of the greater trochanter, the gluteal muscle branch of the greater trochanter bone and so on50.

Bone grafts with a muscle pedicle commonly utilize the femoral quadratus56.

Allogeneic or autologous fibular grafts are supported by bone graft products57, 58.

Impaction bone grafting can utilize autologous bone or allograft bone, with or without bone morphogenetic protein 259.

Osteotomy most commonly takes the form of femoral neck rotational osteotomy through the greater trochanter60, 61, varus subtrochanteric osteotomy62 and others.

The choice of tantalum rod should made with care; it is not recommended with vascular intervention therapy alone63.

Arthroplasty

Most patients with ONFH will eventually have to undergo arthroplasty. With improvements in artificial joint design, materials and technique, the scope for joint‐preserving procedures is decreasing, whereas the indications for arthroplasty are expanding64, 65, 66.

The type of artificial joint can be selected according to the following recommendations:

Resurfacing has a limited role in subjects with ONFH because of the complications associated with metal‐on‐metal bearing surfaces.

Femoral head replacement is rarely indicated because postoperative pain and acetabular wear is unpredictable.

A short stem femoral prosthesis is currently under development.

Total hip arthroplasty is the most classical and mature artificial joint with lasting benefit and is appropriate for most ONFH patients with stage IV and V disease. For young patients, bearing surfaces (ceramic‐on‐ceramic, ceramic‐on‐highly cross‐linked polyethylene) and biological bone ingrowth prostheses are recommended.

Principles for Treatment Selection

Selection of ONFH treatment options must be individualized choice according to the site(s) of necrosis, stage, classification, age and occupation of the patient; individualized joint‐preserving procedures should be considered. The same treatment selection principles apply to patients with ONFH and silent hips17, 18. Indicated treatments for each stage and type are as follows:

Stage I, II, M‐type: follow‐up, observation or placebo treatment.

Stage I, II, C‐type: extracorporeal shock wave, core decompression or debridement of foci, autologous bone marrow transplantation or bone grafting, medication.

Stage I, II, L1 type: debridement, vascularized or avascularized bone graft, medication. If the patient is aged less than 5 years, varus osteotomy is recommended.

Stage I, II, L2, L3 type: debridement of foci and strut graft (vascularized or avascularized) or impaction bone grafting. If the patient is aged less than 5 years and has L2 type, transtrochanteric rotational osteotomy is recommended.

Stage III: in patients aged less than 50 years, joint‐preserving surgery is usually indicated, the procedures being the same as for stage I, II; L2, L3 type, whereas in patients aged more than 50 years with severe pain and joint dysfunction, arthroplasty is indicated.

Stage IVa, IVb: in patients aged less than 40 years, joint‐preserving should be attempted, whereas in those aged more than 40 years with severe pain and joint dysfunction, arthroplasty is indicated.

Stage IVc and V: in patients with severe pain and joint dysfunction, arthroplasty is indicated.

Evaluation of Outcomes

Outcomes can be evaluated clinically and radiographically5, 67, 68, 69. For clinical assessment, Harris hip function evaluation69, University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) hip joint evaluation70 and European assessment (Postel Merle d'Aubigné)71 can be used. Imaging assessment is mainly based on plain X‐ray films, which can show the femoral head shape, whether or not it has collapsed and joint space changes. Sometimes, especially in young individuals, clinical and radiographic scores are not in accordance; in these cases clinical assessment should be paramount.

Prognosis

Hip‐preservation should be effective in the patients in whom17, 18: (i) a diagnosis has been in stage I or II and available technical skills and treatment options are appropriate; (ii) the osteonecrosis is of M or C type; and (iii) the osteonecrosis is of L1 type and appropriate treatment has been provided.

Patients with disease in the pre‐collapse phase who receive timely treatment are expected to achieve good prognosis, whereas in patients with a longer duration of collapse (>6 months), the prognosis is difficult to predict20, 25. In patients with ONFH of the same phase and type, younger (<35 years) patients have a better prognosis than older patients; thus, the indications for treatment can be more flexible in young patients.

List of names of consultant specialists

Wei‐heng Chen, Sheng‐bao Chen, Li‐ming Cheng, Peng Gao, Wan‐shou Guo, Wei He, Peng‐de Kang, Zi‐rong Li, Jing Li, Hui Qu, Gui‐xing Qiu, Wei Sun, Yi‐sheng Wang, Zheng‐yi Wang, Wei‐guo Wang, Kun‐zheng Wang, Jing‐gui Wang, Xi‐sheng Weng, Geng‐yan Xing, Nan‐sheng Yu, Shu‐hua Yang, Zuo‐qin Yan, Chang‐qing Zhang, Hong Zhang, De‐wei Zhao, Zhen‐zhong Zhu.

Disclosure: No funds were received in support of this work.

Contributor Information

Joint Surgery Group of the Orthopaedic Branch of the Chinese Medical Association:

Wei‐heng Chen, Sheng‐bao Chen, Li‐ming Cheng, Peng Gao, Wan‐shou Guo, Wei He, Peng‐de Kang, Zi‐rong Li, Jing Li, Hui Qu, Gui‐xing Qiu, Wei Sun, Yi‐sheng Wang, Zheng‐yi Wang, Wei‐guo Wang, Kun‐zheng Wang, Jing‐gui Wang, Xi‐sheng Weng, Geng‐yan Xing, Nan‐sheng Yu, Shu‐hua Yang, Zuo‐qin Yan, Chang‐qing Zhang, Hong Zheng, De‐wei Zhao, and Zhen‐zhong Zhu

References

- 1. Mont MA, Jones LC, Hungerford DS. Nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head: ten years later. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2006, 88: 1117–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Powell C, Chang C, Gershwin ME. Current concepts on the pathogenesis and natural history of steroid‐induced osteonecrosis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol, 2011, 41: 102–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weinstein RS. Glucocorticoid‐induced osteonecrosis. Endocrine, 2012, 41: 183–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li ZR. Expert advice on diagnosis and treatment of femoral head necrosis. Zhonghua Gu Ke Za Zhi, 2007, 27: 146–148 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhao DW, Hu YC. Standards for diagnosis and treatment of adult avascular necrosis of the femoral head (2012 Edition). Zhonghua Gu Ke Za Zhi, 2012, 32: 606–610 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jones LC, Hungerford DS. Overview of osteonecrosis of the hip and current treatment options. Curr Opin Orthop, 2003, 14: 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bachiller FG, Caballer AP, Portal LF. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head after femoral neck fracture. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2002, 399: 87–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Powell C, Chang C, Naguwa SM, Cheema G, Gershwin ME. Steroid induced osteonecrosis: an analysis of steroid dosing risk. Autoimmun Rev, 2010, 9: 721–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saito M, Ueshima K, Fujioka M, et al Corticosteroid administration within 2 weeks after renal transplantation affects the incidence of femoral head osteonecrosis. Acta Orthop, 2014, 85: 266–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li ZR, Sun W, Qu H, et al Clinical research on correlation between osteonecrosis and steroid. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi, 2005, 43: 1048–1053 (in Chinese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lieberman JR, Berry DJ, Mont MA, et al Osteonecrosis of the hip: management in the 21th century. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2002, 84: 834–853. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang YS, Li YB, Yin L, Li J, Xiong TB. The pathogenesis of alcohol‐induced osteonecrosis and the preventive effect of puerarin. Zhonghua Xian Wei Wai Ke Za Zhi, 2006, 29: 209–212 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 13. Korompilias AV, Ortel TL, Urbaniak JR. Coagulation abnormalities in patients with hip osteonecrosis. Orthop Clin North Am, 2004, 35: 265–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sun W, Li ZR, Shi ZC, Zhang NF, Zhang YC. Changes in coagulation and fibrinolysis of post‐SARS osteonecrosis in a Chinese population. Int Orthop, 2006, 30: 143–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nakamura J, Harada Y, Oinuma K, Iida S, Kishida S, Takahashi K. Spontaneous repair of asymptomatic osteonecrosis associated with corticosteroid therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus: 10‐year minimum follow‐up with MRI. Lupus, 2010, 19: 1307–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhao DW, Yang L, Tian FD, et al Incidence of osteonecrosis of the femoral head in divers: an epidemiologic analysis in Dalian. Zhonghua Gu Ke Za Zhi, 2012, 32: 521–525 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mont MA, Zywiel MG, Marker DR, McGrath MS. Delanois RE. The natural history of untreated asymptomatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head: a systematic literature review. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2010, 92: 2165–2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lieberman JR, Engstrom SM, Meneghini RM, SooHoo NF. Which factors influence preservation of the osteonecrotic femoral head? Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2012, 470: 525–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li ZR. Osteonecrosis. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House (PMPH), 2012; 112–163. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Qu H. Imaging diagnosis and differential diagnosis of systemic bone necrosis. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House (PMPH), 2009; 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- 21. He W, Chen ZQ, Zhang QW, et al Effects of frog lateral typing on bone strut grafting in treating alcohol‐induced osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Zhonghua Guan Jie Wai Ke Za Zhi, 2011, 5: 27–33 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen SB, Zhang CQ, Yu JM, et al Analysis of imaging characteristics in adult avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Zhonghua Guan Jie Wai Ke Za Zhi, 2008, 2: 17–23 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ito H, Matsuno T, Minami A. Relationship between bone marrow edema and development of symptoms in patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2006, 186: 1761–1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Iida S, Harada Y, Shimizu K, et al Correlation between bone marrow edema and collapse of the femoral head in steroid‐induced osteonecrosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2000, 174: 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. He W, Zeng Q, Zhang QW, et al Study on correlation between pain grading, stage of necrosis and bone marrow edema in nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi, 2008, 22: 299–302 (in Chinese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Oinuma K, Harada Y, Nawata Y, et al Osteonecrosis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus develops very early after starting high dose corticosteroid treatment. Ann Rheum Dis, 2001, 60: 1145–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sugano N, Kubo T, Takaoka K, et al Diagnostic criteria for non‐traumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head: a multicentre study. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 1999, 81: 590–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stevens K, Tao C, Lee SU, et al Subchondral fractures in osteonecrosis of the femoral head: comparison of radiography, CT, and MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2003, 180: 363–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Saini A, Saifuddin A. MRI of osteonecrosis. Clin Radiol, 2004, 59: 1079–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li ZR. Differential diagnosis of hip joint disease of the femoral head. Zhonghua Gu Ke Za Zhi, 2010, 30: 1011–1014 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yamamoto T, Nakashima Y, Shuto T, Jingushi S, Iwamoto Y. Subchondral insufficiency fracture of the femoral head in younger adults. Skeletal Radiol, 2007, 36 (Suppl. 1): S38–S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ficat RP. Idiopathic bone necrosis of the femoral head. Early diagnosis and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 1985, 67: 3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gardeniers JWM. A new international classification of osteonecrosis of the ARCO committee on terminology and classification. J Jpn Orthop Assoc, 1992, 66: 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Steinberg ME, Brighton CT, Corces A, et al Osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Results of core decompression and grafting with and without electrical stimulation. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1989, 249: 199–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Marcus ND, Enneking WF, Massam RA. The silent hip in idiopathic aseptic necrosis. Treatment by bone‐grafting. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1973, 55: 1351–1366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sugano N, Takaoka K, Ohzono K, Matsui M, Masuhara K, Ono K. Prognostication of nontraumatic avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Significance of location and size of the necrotic lesion. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1994, 303: 155–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lu C, Liu HZ, Liu DB, et al Analysis of distribution of lesions in necrosis of the femoral head. Zhongguo Jiao Xing Wai Ke Za Zhi, 2014, 22: 396–400 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen WH, Xie B, Liu DB, et al Effects of core decompression and bone graft surgery on osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Zhonghua Guan Jie Wai Ke Za Zhi, 2014, 8: 578–584 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li ZR, Liu ZH, Sun W, et al The classification of osteonecrosis of the femoral head based on the three pillars structure: China Japan Friendship Hospital (CJFH) classification. Zhonghua Gu Ke Za Zhi, 2012, 32: 515–520 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li ZR. Illustration of revision about the translation in English and abbreviation of classification of osteonecrosis of the femoral head China‐Japan Friendship Hospital (CJFH). Zhonghua Gu Ke Za Zhi, 2012, 32: 994 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lai KA, Shen WJ, Yang CY, Shao CJ, Hsu JT, Lin RM. The use of alendronate to prevent early collapse of the femoral head in patients with nontraumatic osteonecrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2005, 87: 2155–2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Agarwala S, Shah S, Joshi VR. The use of alendronate in the treatment of avascular necrosis of the femoral head: follow‐up to eight years. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 2009, 91: 1013–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Huang LX, Dong TH, Xie DH, Xu M. Preliminary observation of clinical results of treatment for early non‐traumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head with Madopar. Zhonghua Gu Ke Za Zhi, 2010, 30: 641–645 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen WH, Zhou Y, He HJ, Wang RT, Wang ZY, Lin N. Prospective study on Jianpihuogu formula for early‐ and mid‐stage non‐traumatic osteonecrosis of femoral head. Zhonghua Guan Jie Wai Ke Za Zhi, 2013, 3: 287–293 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 45. He W. Scientific treatment of non traumatic femoral head necrosis in traditional Chinese Medicine. Zhonghua Guan Jie Wai Ke Za Zhi, 2013, 7: 284–286 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang CJ, Wang FS, Huang CC, Yang KD, Weng LH, Huang HY. Treatment for osteonecrosis of the femoral head: comparison of extracorporeal shock waves with core decompression and bone‐grafting. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2005, 87: 2380–2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kang P, Pei F, Shen B, Zhou Z, Yang J. Are the results of multiple drilling and alendronate for osteonecrosis of the femoral head better than those of multiple drilling? A pilot study. Joint Bone Spine, 2012, 79: 67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hernigou P, Beaujean F. Treatment of osteonecrosis with autologous bone marrow grafting. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2002, 405: 14–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhao D, Cui D, Wang B, et al Treatment of early stage osteonecrosis of the femoral head with autologous implantation of bone marrow‐derived and cultured mesenchymal stem cells. Bone, 2012, 50: 325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhao DW. The repair and reconstruction of avascular necrosis of femoral head. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House (PMPH), 2003; 230–241 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhao D, Wang B, Guo L, Yang L, Tian F. Will a vascularized greater trochanter graft preserve the necrotic femoral head? Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2010, 468: 1316–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. He W, Li Y, Zhang Q, et al Primary outcome of impacting bone graft and fibular autograft or allograft in treating osteonecrosis of femoral head. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi, 2009, 23: 530–533 (in Chinese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Scully SP, Aaron RK, Urbaniak JR. Survival analysis of hips treated with core decompression or vascularized fibular grafting because of avascular necrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1998, 80: 1270–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jun X, Chang‐Qing Z, Kai‐Gang Z, Hong‐Shuai L, Jia‐Gen S. Modified free vascularized fibular grafting for the treatment of femoral neck nonunion. J Orthop Trauma, 2010, 24: 230–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ian L, Wang KZ, Dang XQ, Wang CS. Long‐term effects of vascularized fibular graft transplantation for avascular necrosis of femoral head. Zhonghua Guan Jie Wai Ke Za Zhi, 2012, 6: 879–887 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wang YS, Zhang Y, Li JW, et al A modified technique of bone grafting pedicled with femoral quadratus for alcohol‐induced osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Chin Med J (Engl), 2010, 123: 2847–2852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yang SH, Wu XH, Yang C, Li J, Xu WH. Clinical observation of allograft cage insertion in combination with decalcified bone matrix and autogenous bone for the treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Zhonghua Guan Jie Wai Ke Za Zhi, 2008, 2: 7–10 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wang Y, Chai W, Wang ZG, Zhou YG, Zhang GQ, Chen JY. Superelastic cage implantation: a new technique for treating osteonecrosis of the femoral head with mid‐term follow‐ups. J Arthroplasty, 2009, 24: 1006–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Li ZR, Sun W, Shi ZC, Wang BL, Zhang QD, Guo WS. Debridement and impacted bone graft mixed with and without bone morphogenetic protein for the treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head: a comparative study. Zhongguo Gu Yu Guan Jie Wai Ke, 2012, 5: 377–381 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sugioka Y, Yamamoto T. Transtrochanteric posterior rotational osteotomy for osteonecrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2008, 466: 1104–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zhang NF, Li ZR, Yang LF, et al Transtrochanteric rotational osteotomy for osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi, 2004, 42: 1477–1480 (in Chinese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ito H, Tanino H, Yamanaka Y, et al Long‐term results of conventional varus half‐wedge proximal femoral osteotomy for the treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 2012, 94: 308–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Mao Q, Wang W, Xu T, et al Combination treatment of biomechanical support and targeted intra‐arterial infusion of peripheral blood stem cells mobilized by granulocyte‐colony stimulating factor for the osteonecrosis of the femoral head: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Bone Miner Res, 2015, 30: 647–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Beaulé PE, Dorey FJ, Le Duff MJ, Gruen T, Amstutz HC. Risk factors affecting outcome of metal‐on‐metal surface arthroplasty of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2004, 418: 87–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Loughead JM, O'Connor PA, Charron K, Rorabeck CH, Bourne RB. Twenty‐three‐year outcome of the porous coated anatomic total hip replacement: a concise follow‐up of a previous report. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2012, 94: 151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Mont MA, Seyler TM, Plate JF, Delanois RE, Parvizi J. Uncemented total hip arthroplasty in young adults with osteonecrosis of the femoral head: a comparative study. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2006, 88 (Suppl. 3): 104–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zhao DW. Postoperative functional assessment of head preserve treatment of osteonecrosis of femoral head. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi, 2007, 87: 2881–2883 (in Chinese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zeng ZH, Yu AX, Yu GR, Tan JH, Xiong J. Postoperative rehabilitation of patients with femoral head necrosis. Zhonghua Wu Li Yi Xue Yu Kang Fu Za Zhi, 2005, 27: 557–558 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 69. Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end‐result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1969, 51: 737–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Daniel J, Pynsent PB, McMinn DJ. Metal‐on‐metal resurfacing of the hip in patients under the age of 55 years with osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 2004, 86 (2): 177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. D'Aubigne RM, Postel M. Functional results of hip arthroplasty with acrylic prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1954, 36: 451–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]