Abstract

This study analyzes trends in the distribution of nurse practitioners and primary care physicians in low-income and rural areas.

Nurse practitioners (NPs) constitute the largest and fastest growing group of nonphysician primary care clinicians.1 As the primary care physician (PCP) shortage persists,1 examination of trends in primary care NP supply, particularly in relation to populations most in need, will inform strategies to strengthen primary care capacity. However, such evidence is limited, particularly in combination with physician workforce trends. We thus characterized the temporal trends in the distribution of primary care NPs in low-income and rural areas compared with the distribution of PCPs.

Methods

We analyzed trends in 50 states and Washington, DC, from 2010 to 2016. Data on population characteristics and PCPs (definition appears in the legend of the Figure) were from the Area Health Resources File, a national data set compiled from multiple validated sources including the US Census Bureau and the American Medical Association.2 Data on primary care NPs (definition appears in the legend of the Figure) were from the National Provider Identifier registry, which contains information on health care professionals who had financial transactions with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.3 These data sources have demonstrated convergent validity in prior studies involving primary care workforce estimates.1,4 We further validated the NP estimates by obtaining comparable results with data from the National Sample Survey of NPs.5 We selected health service area (HSA) as the geographic unit of analysis because it was developed to measure the availability of health care resources (eg, health care professionals). Annual clinician supply was measured as the number of clinicians per 100 000 population in an HSA. Income level in the HSA was assessed by quartile rank of the proportion of population at or below 138% of the federal poverty level; HSA metropolitan, urban, and rural status also was determined.

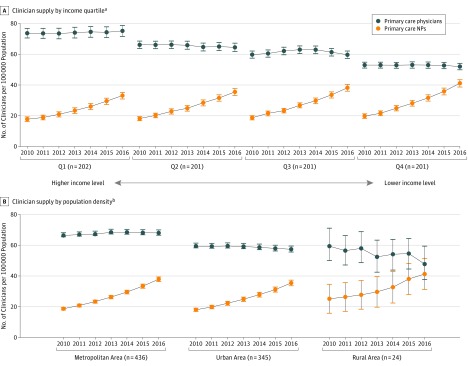

Figure. Trends in the Geographic Distribution of Primary Care Nurse Practitioner (NP) and Primary Care Physician Supply, 2010-2016.

Data on primary care NPs (primary care, adult, family, general gerontology, and general pediatrics, and had an active registration number for full study year) from the National Provider Identifier registry. Data on primary care physicians (nonfederal employees, provided patient care, and held either a doctor of medicine or a doctor of osteopathy degree in general family medicine, general practice, general internal medicine, or general pediatrics) from the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile. The error bars represent 95% CIs.

aIncome quartile defined by proportion of the population with an income level ≤138% of the federal poverty level ($16 394 for a household with 1 individual per year in 2016). The median household income in 2016 was $64 314 for Q1; $52 270 for Q2; $47 227 for Q3; and $39 109 for Q4.

bPopulation density based on the 2013 US Department of Agriculture Rural-Urban Continuum Codes (metropolitan health service area [HSA] included ≥1 metropolitan county; urban HSA, ≥1 urban county with population >2500; and rural HSA, completely rural status or with population <2500).

We calculated clinician supply with 95% CIs and examined the temporal trends in supply across income quartiles and metropolitan, urban, and rural areas, comparing trends between clinician groups using 2-level mixed-effects models that specified intercept and year as random effects and controlled for clustering by HSA. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). A 2-sided P<.05 was considered statistically significant. The study was exempted by the University of Rochester institutional review board.

Results

From 2010 to 2016, the number of primary care NPs increased from 59 442 to 123 316, and the number of PCPs increased from 225 687 to 243 738. The number of NPs per 100 000 population increased by a mean of 15.3 (95% CI, 14.1-16.4) in the highest income quartile to 21.4 (95% CI, 19.9-22.8) in the lowest income quartile (Table). In contrast, physician supply remained relatively constant (Figure, part A). Overall, NP supply increased more than physician supply (annual change, 3.0 vs −0.02, respectively; difference of 3.1 [95% CI, 2.8-3.3] per 100 000 population per HSA; P < .001). By 2016, NP supply was 33.1 (95% CI, 30.9-35.2) per 100 000 population in the highest income quartile and increased to 41.1 (95% CI, 38.7-43.4) in the lowest income quartile, whereas physician supply declined from 75.1 (95% CI, 71.6-78.6) in the highest income quartile to 52.0 (95% CI, 49.9-54.1) in the lowest income quartile (Table). Similar trends were observed in metropolitan, urban, and rural HSAs (Figure, part B). Primary care NP supply increased more than physician supply by an annual mean of 2.9 (95% CI, 2.6-3.1; P < .001) per 100 000 population in metropolitan areas, 3.2 (95% CI, 2.9-3.5; P < .001) in urban areas, and 4.3 (95% CI, 2.0-6.5; P < .001) in rural areas (Table). By 2016, the highest NP supply was observed in rural HSAs (41.3 [95% CI, 31.2-51.3] per 100 000 population), whereas the highest physician supply was in metropolitan HSAs (68.0 [95% CI, 66.0-70.0] per 100 000 population) (Table).

Table. Primary Care Nurse Practitioner Supply and Primary Care Physician Supply for 805 Health Service Areas (HSAs), 2010-2016a.

| Primary Care Nurse Practitioners (NPs) | Primary Care Physicians | NPs vs Physicians | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95% CI) per 100 000 Populationb | Absolute Mean Change (95% CI)c | Annual Mean Change (95% CI)d | P Valuee | Mean (95% CI) per 100 000 Populationb | Absolute Mean Change (95% CI)c | Annual Mean Change (95% CI)d | P Valuee | Annual Mean Change (95% CI)f | P Valuee | |||

| 2010 | 2016 | 2010 | 2016 | |||||||||

| Total No. | 59 442 | 123 316 | 63 874g | 12.9%h | 225 687 | 243 738 | 18 051g | 1.3%h | ||||

| Supplyi | 18.6 (17.9-19.3) | 37.0 (35.8-38.1) | 18.3 (17.7-19.0) | 3.0 (2.9-3.1) | <.001 | 63.2 (61.8-64.5) | 62.8 (61.4-64.3) | −0.3 (−0.9 to 0.3) | −0.02 (−0.13 to 0.08) | .66 | 3.1 (2.8-3.3) | <.001 |

| Clinician Supply by Income Quartile | ||||||||||||

| Q1j | 17.8 (16.3-19.3) | 33.1 (30.9-35.2) | 15.3 (14.1-16.4) | 2.6 (2.4-2.8) | <.001 | 73.7 (70.6-76.8) | 75.1 (71.6-78.6) | 1.5 (0.3 to 2.8) | 0.26 (0.03 to 0.48) | .03 | 2.3 (1.9-2.8) | <.001 |

| Q2 | 18.2 (16.8-19.5) | 35.5 (33.1-37.9) | 17.3 (15.8-18.8) | 3.0 (2.8-3.2) | <.001 | 66.2 (63.8-68.6) | 64.5 (61.8-67.2) | −0.2 (−1.8 to 1.4) | −0.07 (−0.28 to 0.14) | .53 | 3.2 (2.8-3.6) | <.001 |

| Q3 | 18.7 (17.3-20.1) | 38.2 (36.0-40.4) | 19.3 (17.7-20.9) | 3.2 (3.0-3.4) | <.001 | 59.8 (57.5-62.1) | 59.7 (57.3-62.1) | −1.8 (−3.3 to −0.3) | −0.17 (−0.37 to 0.02) | .09 | 3.1 (2.7-3.4) | <.001 |

| Q4k | 19.8 (18.3-21.3) | 41.1 (38.7-43.4) | 21.4 (19.9-22.8) | 3.4 (3.2-3.7) | <.001 | 52.9 (51.0-54.9) | 52.0 (49.9-54.1) | −1.5 (−2.8 to −0.3) | −0.16 (−0.35 to 0.04) | .11 | 3.6 (3.3-4.0) | <.001 |

| Clinician Supply by Population Density | ||||||||||||

| Metropolitan | 18.7 (17.9-19.6) | 37.9 (36.4-39.4) | 19.2 (18.4-19.9) | 3.2 (3.0-3.3) | <.001 | 66.4 (64.6-68.1) | 68.0 (66.0-70.0) | 1.6 (1.1 to 2.1) | 0.30 (0.22 to 0.39) | <.001 | 2.9 (2.6-3.1) | <.001 |

| Urban | 18.0 (16.9-19.1) | 35.5 (33.7-37.3) | 17.4 (16.3-18.5) | 2.9 (2.7-3.1) | <.001 | 59.4 (57.4-61.4) | 57.4 (55.4-59.5) | −2.0 (−3.1 to −0.9) | −0.33 (−0.51 to −0.16) | <.001 | 3.2 (2.9-3.5) | <.001 |

| Rural | 25.2 (15.8-34.6) | 41.3 (31.2-51.3) | 16.1 (10.4-21.8) | 2.7 (1.7-3.7) | <.001 | 59.5 (47.9-71.1) | 47.8 (36.1-59.4) | −11.7 (−21.5 to −1.9) | −1.53 (−3.21 to 0.16) | .07 | 4.3 (2.0-6.5) | <.001 |

For a given HSA, income quartile rank may change but population density status remains the same. The population with an income level ≤138% of the federal poverty level (FPL), defined as $16 394 for a household with 1 individual per year in 2016. The HSA income quartile rank in 2016 was 16% for Q1 (highest income level; median, $64 314); 22% for Q2 ($52 270); 26% for Q3 ($47 227); and 33% for Q4 (lowest; $39 109).

Except for the numbers in the first row.

Indicates change in clinician supply between 2010 and 2016 per 100 000 population.

From mixed-effects model: Y = β0+β1year.

Corresponds to annual mean change.

From mixed-effects model Y = β0+β1year+β2clinician group +β3year × clinician group.

Data are total number from 2016 minus total number from 2010.

Refers to the annual growth rate. Calculated as (end value/beginning value)(1/No. of years) – 1.

Supply is the number of clinicians per 100 000 population in an HSA in a given study year.

Highest income level and has the lowest proportion of population with ≤138% of the FPL.

Lowest income level and has the highest proportion of population with ≤138% of the FPL.

Discussion

This analysis demonstrated a narrowing gap between primary care NP and physician workforce supply over time, particularly in low-income and rural areas. These areas have higher demand for primary care clinicians and larger disparities in access to care.6 The growing NP supply in these areas is offsetting low physician supply and thus may increase primary care capacity in underserved communities. Study limitations include the use of different data sources for NPs and physicians; and it is unknown if observed trends have changed from the most recent data in 2016. Continued monitoring of these trends is warranted.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services National and regional projections of supply and demand for primary care practitioners: 2013-2025. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/health-workforce-analysis/research/projections/primary-care-national-projections2013-2025.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2018.

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services Area Health Resources File: 2017-2018. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/ahrf. Accessed September 10, 2018.

- 3.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services National Provider Identifier registry: 2017. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Administrative-Simplification/NationalProvIdentStand/DataDissemination.html. Accessed May 9, 2017.

- 4.Auerbach DI, Staiger DO, Buerhaus PI. Growing ranks of advanced practice clinicians—implications for the physician workforce. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(25):2358-2360. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1801869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services Highlights from the 2012 national sample survey of nurse practitioners. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/nchwa/npsurveyhighlights.pdf. Accessed September 10, 2018.

- 6.Huang ES, Finegold K. Seven million Americans live in areas where demand for primary care may exceed supply by more than 10 percent. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(3):614-621. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]