Abstract

Here we report the launch of a web-tool (the GLYCAM-Web GAG Builder, www.glycam.org/gag) for the rapid and straightforward prediction of 3D structural models for glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). The tool provides the user with coordinate files (PDB format) for use in visualization, as well as files for performing MD simulation with the AMBER software package. Counter ions and water may also be added as desired. The tool is designed with the non-expert in mind, and as such has implemented typical default values for structural parameters, which the user may change if desired. Multiple GAG types are supported, including Heparin/Heparan Sulfate, Chondroitin Sulfate, Dermatan Sulfate, Keratan Sulfate, and Hyaluronan; however, the user may alter the default sulfation patterns to create novel sequences. The common non-natural unsaturated uronic acid (ΔUA) and its sulfated derivative are also supported.

Introduction

We announce the launch of a web-tool (the GLYCAM-Web GAG Builder, www.glycam.org/gag) for the rapid and straightforward generation of 3D structural models for glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). GAGs are linear polysaccharides, which are often heterogeneously sulfated, that are found in the extracellular matrix where they are frequently covalently attached to proteins. They play important roles in many cellular processes, including the immune response, cell adhesion, cell signaling, and anticoagulation (Esko et al. 2017). Typically composed of alternating hexosamine and uronic acid pairs, GAGs are commonly categorized into five classes (Heparin/Heparan Sulfate, Chondroitin Sulfate, Dermatan Sulfate, Keratan Sulfate, and Hyaluronan) based on unique disaccharide compositions.

Modeling GAGs is complicated by virtue of the variability of the sulfate positions, and by the fact that some of the monosaccharides, particularly iduronic acid (IdoA), adopt more than one ring conformation. Several recent reviews of GAG modeling have appeared, which the reader may find helpful (Samsonov et al. 2014; Almond 2018; Sankaranarayanan et al. 2018; Woods 2018).

Results and discussion

The GAG Builder permits the user to generate 3D models of any of the common GAGs using a simple point-and-click interface. The GAG is then automatically energy minimized and files are provided that permit visualization (PDB format) by a range of software packages. Additionally, the user may download files that enable molecular dynamics simulations to be performed with the AMBER software package (Case et al. 2016).

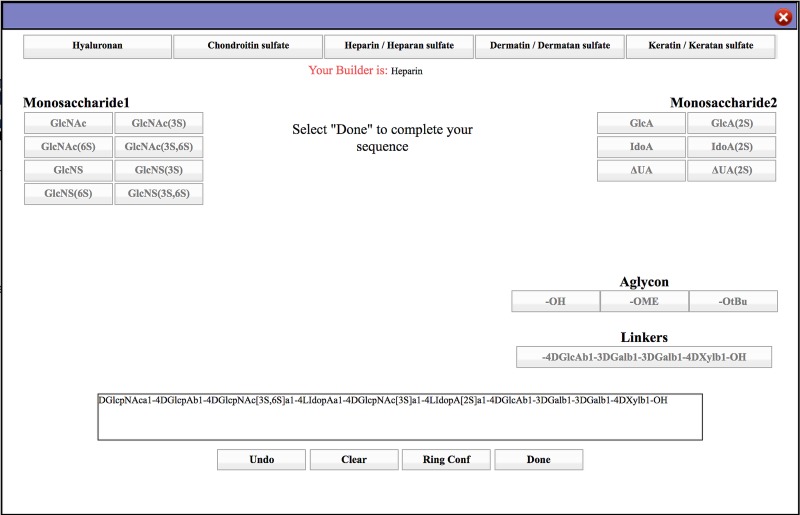

The GAG builder interface (Figure 1) requires the user to make a selection for the class of GAG in order to display the associated set of GAG-specific monosaccharide residues. Each monosaccharide group includes the common sulfation patterns for the GAG class. To reduce the potential for the user to generate a biologically irrelevant sequence, the pattern of alternating monosaccharide types is enforced by separating them (hexosamines on the left, and uronic acids—or galactose and its derivatives in case of KS—on the right) and by alternately deactivating and reactivating each side. When ready, the user can terminate the sequence using a selection of aglycons. Oligosaccharides of heparin or heparan sulfate are often generated by enzymatic degradation of the intact polysaccharide, resulting in the formation of a non-natural unsaturated terminal monosaccharide (Δ4,5-unsaturated uronic acid (ΔUA)) and its sulfated derivative. The GAG-Builder permits the user to select these non-natural residues if desired. Additionally, to accommodate research involving non-standard GAG sequences, the interface allows the user to manually edit the GAG text sequence, for example to generate uncommon sulfation patterns. Lastly, users may switch between GAG classes to allow mixing monosaccharides from different classes into a single sequence.

Fig. 1.

GLYCAM-Web GAG Builder user interface (www.glycam.org/gag).

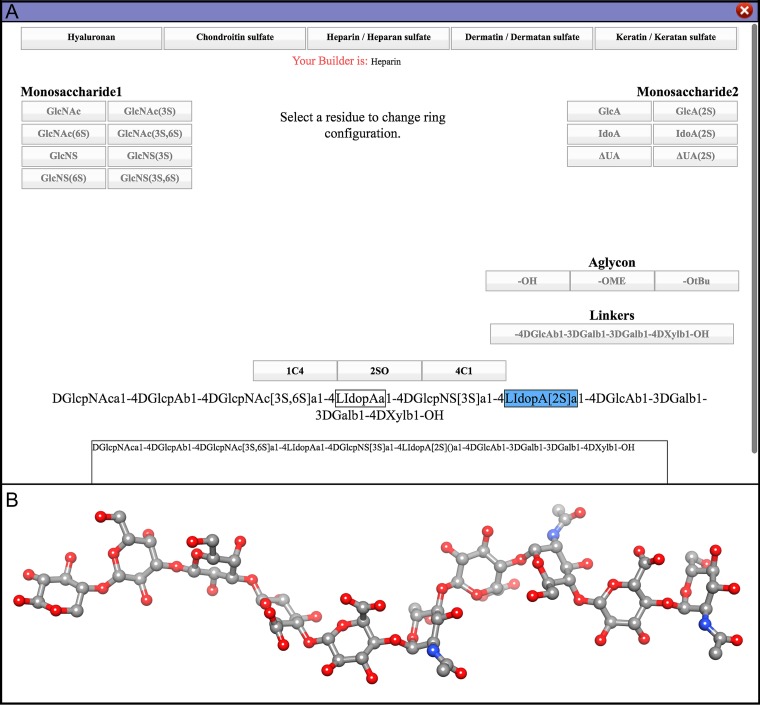

The default conformation for IdoA residue and its derivatives is the most abundant solution conformation (1C4), but the option to model the alternative 2SO and 4C1 conformations (Samsonov et al. 2014; Almond 2018; Sankaranarayanan et al. 2018; Woods 2018) is also provided. The option to change ring shape becomes active once the user terminates the sequence (Figure 2). The GAG builder connects the monosaccharides according to established conformational rules (Woods 2018), and then minimizes the energy of the oligosaccharide using the GLYCAM06 force field (Kirschner et al. 2008), augmented with GAG specific parameters (Singh et al. 2016). Users with specific requirements have the option to assign desired values for these angles, which may be appropriate in case of protein bound structures where the glycosidic angles can differ from the solution (or theoretical) conformation (Figure 3). Upon completion of the sequence selection, the user may add counter ions (Na+ or Cl-) to achieve charge neutrality and may solvate the oligosaccharide with water, as commonly required for MD simulations.

Fig. 2.

(A) View of the GAG Builder showing the option to choose alternate conformations of IdoA residues, (B) Ball-and-stick representation of heparin structure built using the GAG Builder.

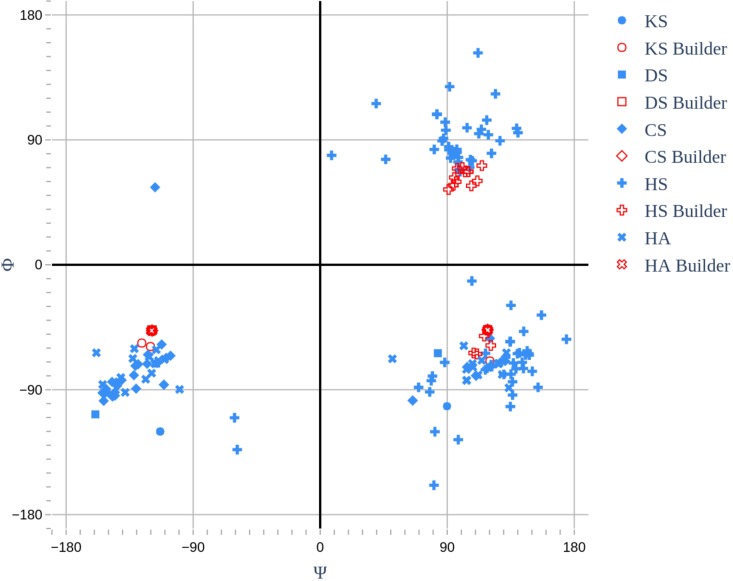

Fig. 3.

Comparison of Φ- and Ψ-glycosidic angles for all GAGs found in the PDB (blue), and for the same structures generated using the GAG Builder (red). The structures were limited to those with average oligosaccharide B-factors of less than 50. We have adopted the crystallographic definition for the glycosidic angles, namely, Φ = O5-C1-Ox-Cx, and Ψ = C1-Ox-Cx-Cx-1.

In order to improve and further develop the GLYCAM-Web modeling services, we encourage user feedback (www.glycam.org/contact).

Funding

R.J.W. thanks the National Institutes of Health (U01 CA207824, U01 CA221216 and P41 GM103390) for financial support.

References

- Almond A. 2018. Multiscale modeling of glycosaminoglycan structure and dynamics: current methods and challenges. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 50:58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case DA, et al. 2016. AMBER. San Francisco: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Esko JD, H. Prestegard J, Linhardt RJ. 2017. Proteins that bind sulfated glycosaminoglycans, Chapter 38. In: Varki A, Cummings RD, Esko JD, et al., editors. Essentials of glycobiology [Internet]. 3rd edition. Cold Spring Harbor (NY): Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschner KN, Yongye AB, Tschampel SM, González-Outeiriño J, Daniels CR, Foley BL, Woods RJ. 2008. GLYCAM06: a generalizable biomolecular force field. Carbohydrates. J Comput Chem. 29(4):622–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samsonov SA, Theisgen S, Riemer T, Huster D, Pisabarro MT. 2014. Glycosaminoglycan monosaccharide blocks analysis by quantum mechanics, molecular dynamics, and nuclear magnetic resonance. BioMed Res Int. 2014:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankaranarayanan NV, Nagarajan B, Desai UR. 2018. So you think computational approaches to understanding glycosaminoglycan-protein interactions are too dry and too rigid? Think again! Curr Opin Struct Biol. 50:91–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Tessier MB, Pederson K, Wang X, Venot AP, Boons GJ, Prestegard JH, Woods RJ. 2016. Extension and validation of the GLYCAM force field parameters for modeling glycosaminoglycans. Can J Chem. 94(11):927–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods RJ. 2018. Predicting the structures of glycans, glycoproteins, and their complexes. Chem Rev. 118(17):8005–8024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]