Abstract

GalNAc-type O-glycans are often added to proteins post-translationally in a clustered manner in repeat regions of proteins, such as mucins and IgA1. Observed IgA1 glycosylation patterns show that glycans occur at similar sites with similar structures. It is not clear how the sites and number of glycans added to IgA1, or other proteins, can follow a conservative process. GalNAc-transferases initiate GalNAc-type glycosylation. In IgA nephropathy, an autoimmune disease, the sites and O-glycan structures of IgA1 hinge-region are altered, giving rise to a glycan autoantigen. To better understand how GalNAc-transferases determine sites and densities of clustered O-glycans, we used IgA1 hinge-region (HR) segment as a probe. Using LC-MS, we demonstrated a semi-ordered process of glycosylation by GalNAc-T2 towards the IgA1 HR. The catalytic domain was responsible for selection of four initial sites based on amino-acid sequence recognition. Both catalytic and lectin domains were involved in multiple second site-selections, each dependent on initial site-selection. Our data demonstrated that multiple start-sites and follow-up pathways were key to increasing the number of glycans added. The lectin domain predominately enhanced IgA1 HR glycan density by increasing synthesis pathway exploration by GalNAc-T2. Our data indicated a link between site-specific glycan addition and clustered glycan density that defines a mechanism of how conserved clustered O-glycosylation patterns and glycoform populations of IgA1 can be controlled by GalNAc-T2. Together, these findings characterized a correlation between glycosylation pathway diversity and glycosylation density, revealing mechanisms by which a single GalNAc-T isozyme can limit and define glycan heterogeneity in a disease-relevant context.

Keywords: clustered glycosylation, GalNAc-transferase, IgA1 hinge region, O-glycosylation, restricted glycan heterogeneity

Introduction

Mucin-type (GalNAc-type) O-glycosylation is a common post-translational modification, frequently occurring on proteins that transit through the Golgi complex (Hanisch 2001). The addition and processing of O-glycans by glycosyltransferases in the Golgi complex often affect protein function, thereby adding a level of post-translational control. GalNAc-type O-glycosylation, a non-template driven process, is initiated in humans by a family of twenty polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase (GalNAc-T) enzymes that add GalNAc to S/T amino acid residues (Clausen and Bennett 1996; Wandall et al. 1997; Gerken et al. 2008; Bennett et al. 2012). In many instances, the O-glycans are added in a highly clustered fashion, such as in the case of mucin repeats (Van Klinken et al. 1995) and IgA1 hinge region (HR) (Baenziger and Kornfeld 1974; Tomana et al. 1976; Field et al. 1989; Renfrow et al. 2007). Despite the potential for high complexity of clustered O-glycans on circulatory IgA1 or mucins resulting from combinatorial expansion associated with a stepwise process involving many enzymes, these glycoproteins exhibit a restricted set of glycosylation products, both in terms of sites of glycosylation and glycan structures observed at each site (Gerken et al. 2002; Pratt et al. 2004; Knoppova et al. 2016; Novak et al. 2016). This raises a question on how a non-template driven step-wise process can reproducibly create a limited variety of similar glycoprotein products characterized by clustered glycosylation with a restricted heterogeneity. GalNAc-Ts play a major role in governing the patterns of the restricted heterogeneity by defining the sites and density of glycosylation, although other mechanisms are also likely involved (Young 2004; Nilsson et al. 2009; Lorenz et al. 2016).

In the autoimmune chronic kidney disease IgA nephropathy (IgAN), the heterogeneity of clustered O-glycans of IgA1 HR is altered and can be described as a shift in the glycan structures to contain less galactose (Gal) and, at the same time, have a higher content of GalNAc in the overall distribution of IgA1 HR glycoforms when compared to normal IgA1 (Suzuki et al. 2011; Novak et al. 2012, 2016; Lai et al. 2016). These shifts in the heterogeneity produce an autoantigen, IgA1 with terminal GalNAc, that is recognized by autoantibodies specific for Gal-deficient IgA1 in patients with IgAN (Knoppova et al. 2016). Binding of Gal-deficient IgA1 molecules by the autoantibodies results in the formation of pathogenic immune complexes in the circulation, some of which deposit in the glomeruli and incite renal injury (Mestecky et al. 1993; Suzuki et al. 2009). The IgA1 HR (Table I), like other GalNAc-T substrates, is an extended proline (Pro)-rich region connecting the heavy-chain Fd and Fc regions. Glycans of IgA1 HR are simple core 1 structures, and usually occur at three to six of the nine potential O-glycosylation sites. The sites where glycans often occur are 225, 228, 230, 232, 233 and 236 of IgA1 heavy chain, of which sites 230, 233 and 236 frequently exhibit Gal-deficiency (Tomana et al. 1999; Novak et al. 2007, 2012; Renfrow et al. 2007; Takahashi et al. 2010, 2012; Franc et al. 2013).

Table I.

Synthetic peptides and glycopeptides

| Peptide name | Sequence | Description |

|---|---|---|

| HR | VPSTPPTPSPSTPPTPSPSCCHPR | Native IgA1 HR peptide |

| HRAA | VPSTPPTPSPSTPPTPSPSAAHPR | C20C21to A20A21variant |

| HRT7A | VPSTPPAPSPSTPPTPSPSCCHPR | T7to A7variant |

| HRT15A | VPSTPPTPSPSTPPAPSPSCCHPR | T15to A15variant |

| HRAAT*7GalNAc | VPSTPPT*PSPSTPPTPSPSAAHPR | 1stsite T7a |

| HRAAT*15GalNAc | VPSTPPTPSPSTPPT*PSPSAAHPR | 1stsite T15a |

| HRAAS*9GalNAc | VPSTPPTPS*PSTPPTPSPSAAHPR | 1stsite S9a |

| HRAAS*11GalNAc | VPSTPPTPSPS*TPPTPSPSAAHPR | 1stsite S11a |

aSite of α-linked GalNAc incorporation.

Early investigations have indicated that although multiple GalNAc-Ts were expressed in IgA1 producing cells, only GalNAc-T2 exhibited activity towards IgA1 HR peptide when expressed as a recombinant enzyme (Iwasaki et al. 2003). The reported order of glycosylation for IgA1 HR by GalNAc-T2, however, does not correlate with the patterns of HR glycosylation of serum IgA1 (Novak et al. 2012). Other studies showed that several additional GalNAc-T isozymes have activity towards IgA1 HR (Wandall et al. 2007). In addition, the lectin domain of GalNAc-T2 was shown to be involved in increasing IgA1 HR glycosylation (Wandall et al. 2007). Still, the impact of the lectin domain on IgA1 O-glycosylation biosynthetic pathways is not clearly understood, particullarly in a way that would allow clear differentiation among different GalNAc-T isozymes.

GalNAc-Ts contain a variety of structural features that offer multiple potential mechanisms to control the initial and follow-up steps of clustered O-glycosylation. These mechanisms can likely differentiate between GalNAc-T isozymes. Most important is the concerted actions of both the catalytic domain, responsible for addition of GalNAc to S/T residues, and the lectin domain, involved in carbohydrate and peptide binding during follow-up and initial glycosylation respectively (Ten Hagen et al. 2003; Fritz et al. 2004; Wandall et al. 2007; Ji et al. 2018). A dynamic interplay between both domains has been observed during initiation of clustered glycosylation (Raman et al. 2008; Gerken et al. 2011; Lira-Navarrete et al. 2015). The two domains are separated by a linker region that is flexible in some GalNAc-Ts and more rigid in others, providing isozyme-specific constraints during glycosylation initiation and adding further variation to the family of GalNAc-Ts (Fritz et al. 2004; Rivas et al. 2017).

Initial glycosylation events occur due to isozyme-specific amino-acid sequence recognition by the catalytic domain of GalNAc-Ts (Gerken et al. 2006). The amino acid T is generally preferred over S, and surrounding amino acids help define which sites GalNAc-Ts recognize and glycosylate (Hagen et al. 1993; Gerken et al. 2006). Each GalNAc-T has a preferred recognition motif, many of which have been defined by identifying three to five amino acids surrounding a glycosylation site by using random amino-acid peptide substrates and peptide libraries (Gerken et al. 2011; Kong et al. 2015). After initial GalNAc attachment, additional GalNAc residues are added in a manner that depends on the initial site of attachment and GalNAc-T isozymes present (Iida et al. 1999, 2000; Kato, Takeuchi, Kanoh et al. 2001; Kato, Takeuchi, Miyahara 2001, Takeuchi et al. 2002; Gerken et al. 2013; Revoredo et al. 2016). The lectin domain plays a role in follow-up glycosylation, whereby the lectin domain binds to previously glycosylated residues and positions the catalytic domain in close proximity to additional potential clustered-sites of glycosylation (Fritz et al. 2006; Wandall et al. 2007; Raman et al. 2008; Pedersen et al. 2011; Revoredo et al. 2016). High density glycosylation can also occur due to the concerted effort of multiple GalNAc-Ts that act in a hierarchical manner where some prefer peptides and likely initiate glycosylation (such as T1, T2, T5) and others prefer glycopeptides and have either intermediate (T3, T4) or late (T10) GalNAc-T activity (Pratt et al. 2004). The intrinsic variety of these features among GalNAc-Ts may explain variability among glycosylation substrates, sites, and densities across the family of GalNAc-Ts and likely heavily influences the final restricted clustered glycan heterogeneity observed in IgAN (Kong et al. 2015; Revoredo et al. 2016).

Enzyme reactions are dependent on the concentrations of reactants and products. During progressive reactions, such as the synthesis of IgA1 clustered O-glycans, the concentrations of reactants and products fluctuate, as the reaction products become reaction substrates. Thus, each addition of a GalNAc residue by GalNAc-T produces a new substrate for a subsequent reaction. This new substrate is then used by the enzyme and GalNAc residues are added at a rate concordant with the new substrate. This multi-step process, involving short-range and long-range effects of prior glycosylation, in the end produces a “final” glycan density and glycoform distribution. The acceptor sites where a GalNAc residue is attached in IgA1 HR can vary, creating a plethora of positional isomers that each serves as a distinct substrate for the GalNAc-T. Thus, the amount of initial product from the first GalNAc addition plays a role in the follow-up steps, as would the products from each subsequent step. In combination with the sites of glycosylation, the rates of glycosylation will dictate the final quantitative distribution of glycoforms present in a given population. The existence of naturally occurring IgA1 HR amino-acid positional glycosylation isomers suggests that multiple pathways of GalNAc addition to the IgA1 HR exist (Takahashi et al. 2012), creating a puzzle of how a final reproducible heterogeneity at a set number of sites occurs.

IgA1 in IgAN presents a model where two fundamentally different distributions of glycan heterogeneities have been observed and characterized (Baenziger and Kornfeld 1974; Novak et al. 2000, 2012). To better understand the process of clustered O-glycosylation in IgAN and the role of the initiating enzymes in that process, we studied the glycosylation of IgA1 HR by GalNAc-T2. We determined the number and sites of GalNAc O-glycans for each product during the initial steps of clustered glycan synthesis. Our data showed that multiple sites are utilized by GalNAc-T2 for the initial glycan addition. Using multiple IgA1 HR (glyco)peptide substrates and GalNAc-T2 constructs, we identified novel mechanisms by which the alternative initial sites of GalNAc attachment by GalNAc-T2 regulate both site specificity and, surprisingly, glycosylation density of the clustered O-glycans of IgA1 HR. Our results have implications for the altered IgA1 O-glycan heterogeneity patterns observed in patients with IgAN and the tools we developed for the analysis of GalNAc-T2 have the potential to help further differentiate the enzymatic activity of this family of glycosyltransferases.

Results

Assessment of clustered enzymatic activity of GalNAc-T2

To assess the clustered enzymatic activity of GalNAc-T2, we performed a series of time-course reactions with synthetic IgA1 HR peptides containing up to nine potential glycosylation sites (Table I). Quenched reaction products were analyzed using reverse-phase liquid chromatography linked in-line with mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and electron transfer dissociation (ETD) tandem MS (MS/MS) (Figure S1A). This method provides considerable advantage in the analysis of reaction products with multiple additions of GalNAc to T/S residues in close proximity, such as the tandem repeats of IgA1 HR, compared to GalNAc-T enzyme assays that characterize the total addition of radiolabeled GalNAc. Importantly, early steps in the mechanism of clustered O-glycan addition by GalNAc-T2 can be precisely defined, specifically by comparison to GalNAc-T2 mutant constructs that abrogate or eliminate lectin domain activity.

Reaction products, consisting of IgA1 HR glycopeptides with between 1 and 7 GalNAc addition(s) were readily observed in the mass spectra (Figure S1B) and allowed for relative quantitation of the resultant glycoforms of the GalNAc-T enzyme reactions at various time points (Figure S1C). Analysis of time-course reactions demonstrated the consumption of the substrate peptide and the increase of a population of single and multiple additions of GalNAc to the IgA1 HR peptide substrate (Figure S1D). During optimization of reaction conditions, we observed the consistency of the reaction products ionization and relative distributions for both technical (Figure S1E) and experimental replicates (Figure S1F). The observed reproducibility of technical replicates was consistent with our previous analysis of native IgA1 HR populations and demonstrated that the ionization of reaction products was primarily driven by the peptides rather than attached glycan (Renfrow et al. 2005, 2007; Takahashi et al. 2010, 2012). Combined with the ability to localize individual sites of addition by ETD MS/MS, analysis of the GalNAc-T2 reaction products could provide novel molecular insights into the mechanism of clustered O-glycan synthesis.

The lectin domain of GalNAc-T2 plays an early role during clustered glycan synthesis

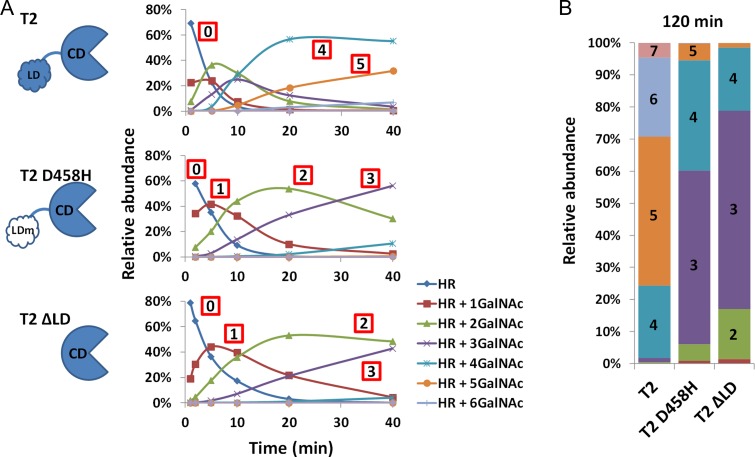

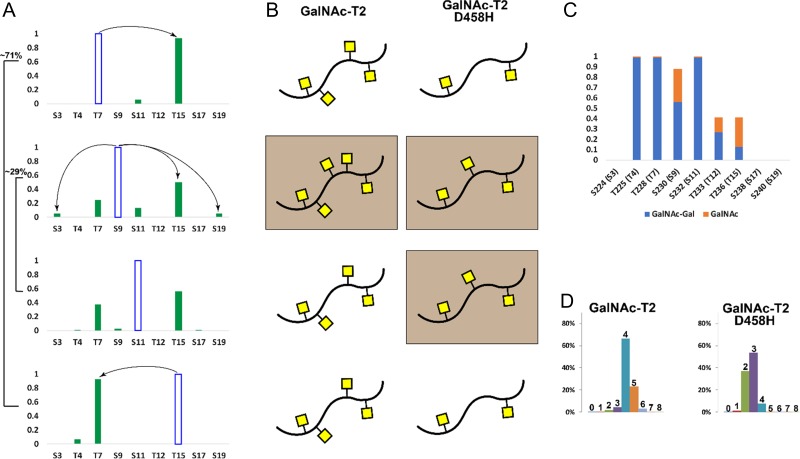

The lectin domain of GalNAc-Ts has been shown to play a role in the rate of clustered glycosylation for IgA1 HR (Wandall et al. 2007). We performed a similar series of time-course reactions on IgA1 HRAA synthetic peptide (Table I), with soluble wild-type GalNAc-T2 (hereafter GalNAc-T2), GalNAc-T2 D458H (a previously characterized lectin domain GalNAc-binding-mutant), and GalNAc-T2 ΔLD (lectin domain deleted) (Figure 1) (Wandall et al. 2007). Enzyme variants were normalized based on protein amount as well as enzyme activity with a single-site acceptor peptide. The enzyme amounts were further refined empirically based on activity during preliminary time-course experiments using multi-site acceptor peptide and normalization based on the first GalNAc added. By applying semi-quantitative assessment of reaction products at each time point, we were able to observe both the progression of the enzyme reactions occurring in each time-course experiment and an indication of the reaction kinetics for each construct.

Figure 1.

GalNAc-T2 lectin domain is essential for high-density glycosylation of IgA1 HR: (A) First 40 min of time-course relative quantification profiles for GalNAc-T2, GalNAc-T2 D458H (lectin domain binding mutant), and GalNAc-T2 ΔLD (lectin domain removed) reactions with IgA1 HR peptide HRAA (VPSTPPTPSPSTPPTPSPSAAHPR). Numbers in red squares indicate number of GalNAc residues added. Value 0 denotes the starting peptide substrate. (B) Relative quantification of reaction endpoints at 120 min for GalNAc-T2 (T2), GalNAcT2 D458H (T2 D458H), and GalNAc-T2 ΔLD (T2 ΔLD).

The reaction profiles of GalNAc-T2 exhibited a fast-addition phase during the first 40 min followed by a slow-addition phase that continued from 40 to 120 min and beyond under defined reaction conditions (Figure S2). GalNAc-T2 generated predominantly glycopeptides with 4 and 5 GalNAc moieties within the fast-addition phase of the reaction (Figure 1A), with the final distribution centered on the glycopeptides with 4, 5 and 6 GalNAc moieties after 120 min (Figure 1B). In contrast, the GalNAc-T2 D458H and GalNAc-T2 ΔLD added 2 to 3 GalNAc moieties during the fast-addition phase and only slightly progressed to the addition of 4 GalNAc moieties after 120 min (Figure 1). Notably, GalNAc-T2 D458H progressed marginally further than GalNAc-T2 ΔLD, potentially alluding to other effects of the lectin domain. While the differences in GalNAc addition are in general agreement with previous analyses of similar constructs of GalNAc-T2 (Wandall et al. 2007), we were also able to see additional details about the early steps of clustered glycan synthesis.

Interestingly, visualization of quantitative profiles of reaction products over time revealed glycoform-specific differences between enzyme variants. There was a notable increase for GalNAc-T2 compared to the other two variants in the consumption of glycopeptides with 1 GalNAc in the early time-points (indicated by lower peak height for GalNAc-T2) that is also seen in the consumption of the 2-GalNAc glycopeptide by 10 min. This would imply a direct role for the lectin domain in increasing rate as soon as the second GalNAc addition, a function that was significantly impaired in the GalNAc-T2 D458H and GalNAc-T2 ΔLD variants. For this reason, we decided to analyze the early steps of GalNAc addition in greater detail.

GalNAc-T2 follows a semi-ordered glycosylation pathway with four discrete first sites of addition

Although it has been proposed that GalNAc-T2 likely follows a certain glycosylation pathway as it glycosylates IgA1 HR (Iwasaki et al. 2003), some of the sites in the proposed pathways do not match with the glycosylation sites typically observed for serum IgA1 (Takahashi et al. 2012; Novak et al. 2012). Reports on GalNAc addition to mucins have shown that GalNAc-T2 follows an ordered addition of GalNAc (Iida et al. 2000; Kato, Takeuchi, Kanoh et al. 2001; Kato, Takeuchi, Miyahara 2001). Thus it is still unclear how GalNAc-T2 may contribute to the reproducible final heterogeneity of IgA1 clustered O-glycans.

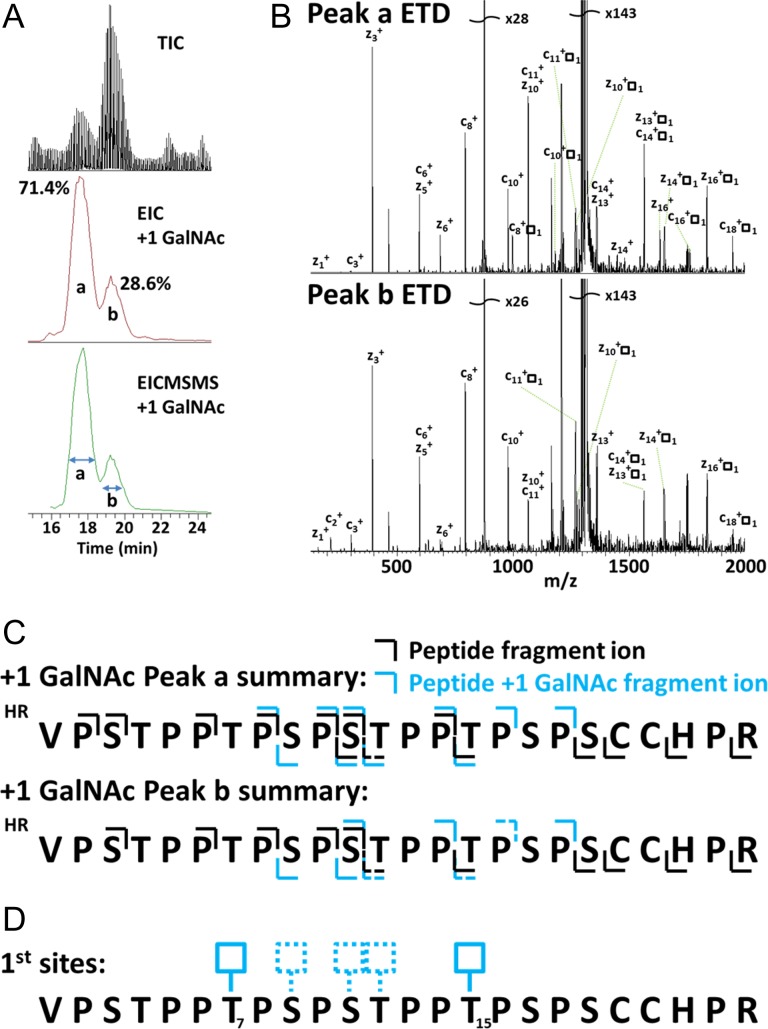

To better characterize this process for IgA1 HR peptide, we optimized buffer conditions for clustered activity that were similar to the pH of the Golgi apparatus and had previously been shown to be within the optimal range for GalNAc-T2 lectin domain binding (pH 6.6) (Paroutis et al. 2004; Pedersen et al. 2011), and analyzed GalNAc-T2 site-specific activity using synthetic IgA1 HR peptides (Table I) and LC-MS with electron transfer dissociation (ETD) in an ion-trap MS. This workflow allowed for robust LC time-scale fragmentation of individual reaction time points to assess the initial steps of the clustered glycan synthesis (Figure 2). The chromatogram of HR with a single GalNAc addition revealed two partially overlapping peaks, designated as peak a (71.4% total) and peak b (28.6% total) (Figure 2A). This result suggested IgA1 HR has multiple initial sites of GalNAc attachment by GalNAc-T2 and there was differential usage of the multiple sites.

Figure 2.

LC-MS with ETD revealed two alternative initial sites of glycan attachment by GalNAc-T2 that correspond to two glycosylation motifs: (A) Top: Total ion current (TIC) LC-MS profile of 5 min GalNAc-T2 reaction with HR peptide. Middle: Extracted ion chromatogram of HR + 1 GalNAc from 5 min GalNAc-T2 reaction. Bottom: Extracted fragment ion chromatogram for ETD scans (EIC-MS/MS) of HR + 1 GalNAc. (B) ETD spectra of peak a (top) and peak b (bottom) averaging over peaks from EIC-MS/MS. (C) HR + 1 GalNAc ETD fragmentation summaries for peaks a and b where top lines are c ions and bottom lines are z ions; black color corresponds to ions with no GalNAc and blue color corresponds to ions with GalNAc. Dotted line indicates ions with low signal intensity, close to background. (D) Overview of the identified alternative first sites (solid boxes; T7 and T15) and additional potential alternative first sites (dashed boxes; S9, S11, and/or T12) for GalNAc-T2 on HR peptide.

Analysis of ETD tandem MS of each ion chromatogram peak, as previously demonstrated by our laboratory (Takahashi et al. 2010, 2012), resulted in identification of two alternative sites of GalNAc attachment, T7 or T15 (Figure 2B–D). These two sites are at identical locations in the two, partially overlapping tandem decapeptide repeats of IgA1 HR: PSTPPT*PSPS, where * is the site of GalNAc attachment. This sequence is similar to the dominant glycosylation motif PGPTPGP, previously identified for GalNAc-T2 (Gerken et al. 2006). The sites identified could not be assigned exclusively to one of the two observed chromatographic peaks, as the ETD fragmentation pattern between peaks a and b showed ambiguity, raising the possibility of additional alternative initial sites of glycosylation (Figure 2C and D).

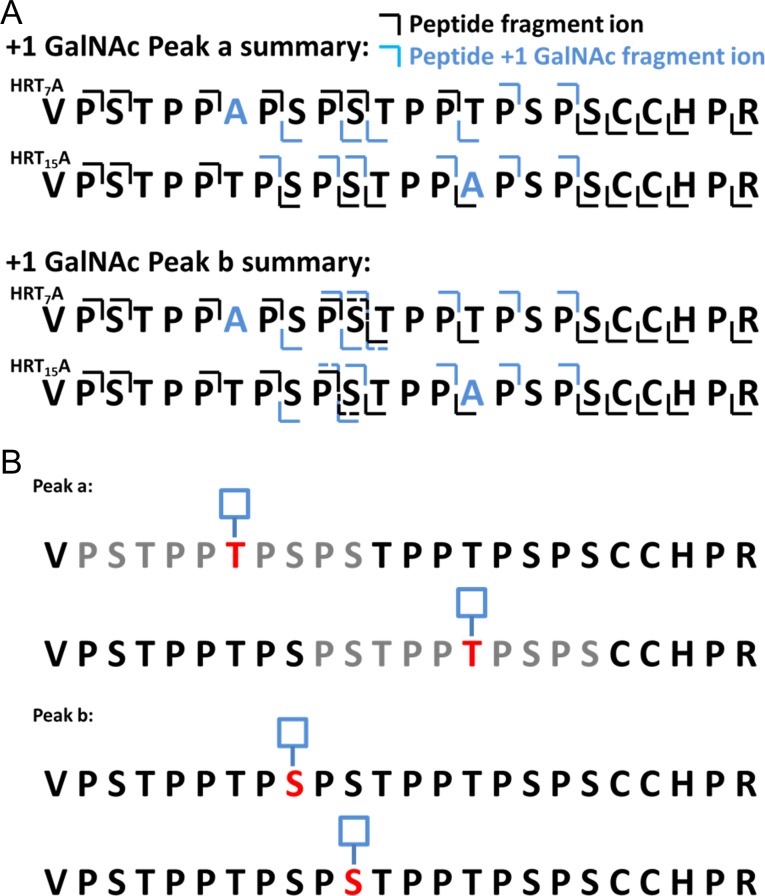

To determine whether additional initial sites of glycosylation occur at residues between the two previously identified sites (T7 and T15), Ala substitutions were made at the corresponding respective first-site T residues to generate the peptides HRT7A and HRT15A (Table I). After enzymatic glycosylation of these peptides with GalNAc-T2, the sites of attachment were determined using ETD LC-MS fragmentation of the respective peptides with 1 GalNAc attachment. Analysis of ETD-generated fragments of HRT7A and HRT15A +1 GalNAc peaks corresponding to peaks a and b revealed a total of four initial sites of glycosylation among the nine potential sites in IgA1 HR (Figures 3A and S3). Peak a (71.4%) consisted of the peptide with a GalNAc at either T7 or T15. Peak b (28.6%) consisted of the peptide with a GalNAc at either S9 or S11 (Figure 3A and B). Peak a was consistently larger than peak b (Figures 2A and S3A-B), suggesting a preference of GalNAc-T2 for one of the two T glycosylation motifs (T7 and T15). The results with the Ala-substituted peptides agreed with the native peptide, but also allowed unambiguous assignment of four alternative sites of attachment. While the number of initial sites was unexpected based on a previous report (Iwasaki et al. 2003), each of the four identified initial sites of glycan attachment corresponds to the known glycosylated sites in serum IgA1 HR. These data demonstrated the formation of four distinct isomers at the first step of IgA1 clustered O-glycan synthesis. Notably, the same four alternative initial sites were consistently identified at similar ratios of T7 and T15 to S9 and S11 throughout the time-course sampling of HR + 1 GalNAc. The enzyme variants GalNAc-T2 D458H and GalNAc-T2 ΔLD showed similar usage of these four initial sites of glycosylation. Additionally, all four initial sites correlated well with isozyme-specific mucin-type glycosylation prediction using University of Texas at El Paso online tool ISOGlyP both before and after recommended and experimentally adjusted correction factors for Ser were applied (Figure S4) (Gerken et al. 2006, 2008, 2011; Perrine et al. 2009; Kong et al. 2015). Analysis of the IgA1 HR in ISOGlyP indicates the same four initial sites we identified experimentally would also be preferred by several other isozymes (Figure S4) Thus, the sites we identified for the initial steps of O-glycan synthesis by GalNAc-T2 may also be used by alternative isozymes. However, the quantitative distribution of IgA1 HR isomers may change. Together these results suggest initial site preference is largely governed by catalytic domain site recognition.

Figure 3.

GalNAc-T2 glycosylates four potential initiation sites within IgA1 HR: (A) HR7A +1 GalNAc and HR15A +1 GalNAc ETD fragmentation summaries for peak a and peak b where top lines are c ions and bottom lines are z ions; black color marks ion with no GalNAc and blue color ion with GalNAc. Dotted line indicates ions with low signal intensity, close to background. (B) Summary of the four initial sites of glycosylation within IgA1 HR by GalNAc-T2 determined from ETD fragmentation of HR, HR7A, and HR15A with 1 GalNAc residue. Peak a (dominant) consists of glycopeptides with two alternative T start sites that contain the motif highlighted in gray (PSTPPT*PSPS). Peak b (minor) consists of glycopeptides with two alternative S start sites (S9, S11) between the two T start sites (T7, T15).

The second sites of addition are dependent upon both the location of the first site and the availability of the “preferred” amino acid motif

Based on the clear identification of four initial sites of GalNAc addition, we hypothesized that this mixture could define unique pathways for subsequent additions. Although previous reports have suggested two possible pathways (Iwasaki et al. 2003), our novel finding indicated even more promiscuity in the catalytic domain’s sequence specificity. To determine the effects of the initial site of glycosylation on the second site of glycosylation, we synthesized four glycopeptides corresponding to the four initial sites of glycosylation, HRAAT*7GalNAc, HRAAT*15GalNAc, HRAAS*9GalNAc, and HRAAS*11GalNAc, hereafter called HRT*7, HRT*15, HRS*9, and HRS*11, respectively (Table I).

After glycosylating the one-GalNAc glycopeptides with GalNAc-T2, analysis of LC-MS ETD fragmentation data for glycopeptide populations with two GalNAc additions revealed the second sites of GalNAc attachment for each initial site. Interestingly, the second sites of addition further increased the pathway diversity being sampled by the enzyme as each unique first site substrate produced a unique 2 GalNAc addition ion chromatogram of multiple isomers (Figure 4 and summarized in Figure 7A). For HRT*7, the second site was consistently a mixture of glycopeptides with the second GalNAc at Ser11 (minor peak) or T15 (major peak), both C-terminally located from the original first site at T7 (Figure 4A and B). For HRT*15, the second site was consistently in the N-terminal direction, at T4 (minor peak) or T7 (major peak). The results from HRT*15 glycopeptide are consistent with previous reports that demonstrated GalNAc-T2 prefers lectin domain dependent follow-up glycosylation of sites located six to ten amino acid residues N-terminally from the previously glycosylated sites (Gerken et al. 2013). Moreover, serum IgA1 does not usually contain glycans C-terminally of T15 (corresponding to T236 in IgA1 heavy chain) (Novak et al. 2000; Takahashi et al. 2010, 2012). The major second sites for each of the two T motifs, T7 and T15, were at the respective remaining non-glycosylated T glycosylation motif PSTPPT*PSPS (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

The second site of GalNAc addition by GalNAc-T2 is restricted by the initial site of GalNAc attachment: (A) Summary of observed second sites of GalNAc addition for HRAAT*7GalNAc +1 GalNAc, HRAAT*15GalNAc +1 GalNAc, HRAAS*9GalNAc +1 GalNAc, and HRAAS*11GalNAc +1 GalNAc (two GalNAc residues per HR). Blue boxes correspond to synthetic sites of GalNAc attachment and green boxes represent the second sites of GalNAc attachment by GalNAc-T2. Letters (a, b, c, d) indicate peaks shown in extracted ion chromatograms in panels B and C to estimate relative amounts of glycoforms with GalNAc at each specific site. Red arrows indicate changes in amounts of specific glycoforms when comparing data for GalNAc-T2 in panel B with data for its lectin domain mutant GalNAc-T2 D458H from panel C. (B and C) Extracted ion chromatograms for GalNAc-T2 (B) and GalNAc-T2 D458H (C) products corresponding to data in panel A for population of peptides with +2 GalNAc residues (one synthetic site and one added by GalNAc-T2). Peak labels correspond to sites identified in panel A.

Figure 7.

Summary of findings on how semi-ordered site-specific clustered activity of GalNAc-T2 impacts glycosylation density of IgA1 HR: (A) Summary of the impact of the initial site of glycosylation on the selection of the second site by GalNAc-T2 in comparison to glycosylation patterns of serum IgA1 detailed in panel C. Each of the four initial sites of glycosylation (blue open bars) directs the selection of second sites for GalNAc addition. Although the site selections are heterogeneous and variable, they are concordant with the O-glycosylated sites in serum IgA1 (panel C) (Novak et al. 2012). Blue open bars indicate the respective four initial sites of glycosylation with their usage indicated on far left (based on data shown in Figure 2). Green closed bars reflect relative usage of second sites as estimated from extracted ion chromatogram (shown in Figure 4). Lines with arrows indicate second-sites usage enhanced by functional lectin domain demonstrating how the lectin domain promotes direction to the second site (starting from T7 or T15) and limited diversity (starting from S9). (B) Summary of glycosylation densities achieved after 40-min reaction (fast phase) with GalNAc-T2 (left) or GalNAc-T2 D458H (right) using HR glycopeptides with one GalNAc at the respective start sites indicated in the panel A. Brown-colored boxes indicate densities that are increased as a result of initial glycan position. The lectin domain influences the final density of glycosylation. (C) Summary of O-glycosylated sites in serum IgA1 as reported previously (Novak et al. 2012). (D) Glycosylation densities reached after 40-min reaction with GalNAc-T2 (left) or GalNAc-T2 D458H (right) using non-glycosylated HR peptide. Numbers above the bars indicate number of GalNAc residues per HR peptide.

For HRS*9, the second site was observed at five sites: S3, T7, S11, T15, or S19 (Figure 4A). T15 and T7 were the dominant sites comprising peaks a and b, respectively. GalNAc addition to S3 or S19 comprised the smallest peak, peak c, in the extracted ion chromatogram (EIC) (Figure 4B) followed by the other initial S at S11 in peak d. For HRS*11, there were five observed second sites of GalNAc addition, T4, T7, S9, T15, and S17 (Figure 4). T7 and T15 were again the dominant sites, peaks a and b, respectively, followed by T4 and S17 comprising peak c and, finally, peak d was a glycopeptide with second GalNAc at S9. The two T motif peaks (peak a and b) were more dominant for HRS*11 than for HRS*9. These observations suggested that HRS*9 had the highest level of isomeric diversity (i.e., highest number of different products) in the second site selection. In this context, we use the term isomeric diversity as a qualitative measure referencing a number of positional isomers and their distributional relative usage, i.e., HR glycopeptide with highest number of different products. Together, the results indicate that the second site of GalNAc attachment is dependent upon where the initial GalNAc is attached. Initiation at either T motif leads to a dominant follow up at the remaining motif. Initiation at either S site (especially S9) leads to a larger sampling of alternative sites creating more isomeric diversity while still predominantly adding to the two T motifs.

The lectin domain of GalNAc-T2 has a dual role: reducing isomeric diversity vs. enhancing “sampling” of clustered O-glycan synthesis pathways

Based on the observed kinetic differences in our initial time-course experiments for the 1 and 2 GalNAc addition glycoforms, we next used two lectin domain mutant enzymes, GalNAc-T2 D458H and GalNAc-T2 ΔLD, to determine the role the lectin domain plays in the range of second site diversity we observed. For HRT*7, mutation of the lectin domain resulted in an increase in the level of S11 (peak b) second site usage (Figure 4C and summarized in Figure 7A). Similarly, for HRT*15, mutation of lectin domain increased the usage of T4 (peak b) as the second cite. This observation indicated that the lectin domain of GalNAc-T2 likely worked in tandem with the specificity of the catalytic domain to orient the catalytic domain towards the alternate T motif when a consensus T motif was glycosylated first. In these cases, the lectin domain increased the order of glycosylation by confining which amino acid residues would be glycosylated second.

For HRS*9, peak c consisting of glycopeptides with second sites at S3 and S19 was not present when the GalNAc-T2 D458H was used (Figure 4). In this case, the functional lectin domain increased the number of alternative second sites. Both S3 and S19 are sites not typically glycosylated in serum IgA1 (Takahashi et al. 2012). Additionally, T7 (peak a) increased relative to T15 (peak b) when the lectin domain was not functional, indicating that the lectin domain biased which T motif was used as a second site for glycopeptide HRS*9 (Figure 4). The lectin domain did not significantly change any of the second site usage for the glycopeptide HRS*11 (Figure 4C).

Selection of the first site of glycosylation by GalNAc-T2 on IgA1 HR impacts the glycosylation kinetics and final glycan density

In addition to having higher serum levels of IgA1 with some HR glycans truncated (Gal-deficient), part of the phenotype of IgA1 HR glycans associated with IgAN is a higher density of O-glycans, i.e. more of the potential sites of glycosylation are used. We hypothesized that an alternative selection of the initial site of glycosylation could influence the final glycan density as well as glycosylation kinetics. Our analysis of site-specific GalNAc-attachment supported this hypothesis as it demonstrated alternative pathways (multiple alternative start sites and corresponding follow-up sites) for glycosylation of IgA1 HR, as outlined above. We further characterized the impact that the glycosylation initiation site has on the progressive addition of subsequent glycosylation and final glycan density.

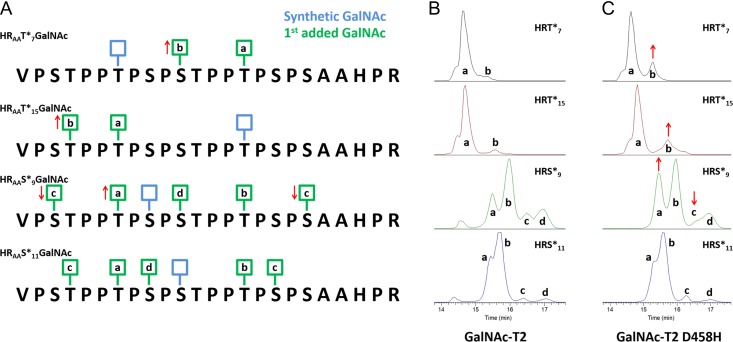

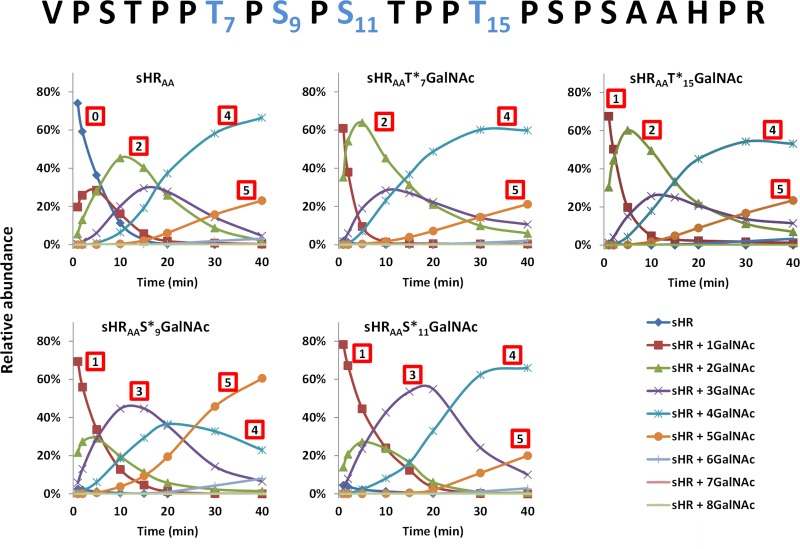

Time-course profiles of GalNAc-T2, GalNAc-T2 D458H, and GalNAc-T2 ∆LD towards peptide and glycopeptide substrates are shown in Figure 5 and Figure S5. Given that the peptide/glycopeptides contained the same peptide backbone, concentrations of purified HRAA peptide and each start-site glycopeptide were normalized using absorbance at 212 nm and then used as acceptor substrates for GalNAc-T2. During the fast-addition phase of the GalNAc-T2 reactions, predominately four GalNAc moieties were added to the non-glycosylated HRAA peptide (Figures 5 and S5). Similar reaction product profiles were observed for the substrates with an initial GalNAc at T7, S11, or T15. Each of these reactions had a predominant four GalNAc clustered O-glycoform product and a lesser five GalNAc O-glycoform. For the start site at S9, an increase to predominantly five GalNAc moieties was observed (Figures 5 and S6). These data demonstrate that the utilization of alternative initial sites of GalNAc attachment can impact the resultant glycosylation rate and final glycan density in IgA1 HR.

Figure 5.

The initial site of glycosylation of IgA1 HR affects the kinetics and final glycan density for GalNAc-T2: Reaction profiles for first 40 min of GalNAc-T2 with peptide/glycopeptides HRAA, HRAAT*7GalNAc, HRAAT*15GalNAc, HRAAS*9GalNAc, and HRAAS*11GalNAc. Relative abundance of each glycoform at each time point is plotted. Top: HRAA sequence with the respective sites of GalNAc attachment for HRAAT*7GalNAc, HRAAT*15GalNAc, HRAAS*9GalNAc, and HRAAS*11GalNAc shown in blue.

For the two T glycosylation start sites (HRT*7, HRT*15), the addition the second GalNAc monosaccharide was very rapid, but subsequent glycosylation proceeded at a lower rate. This allowed for accumulation of the glycopeptides with two GalNAc moieties, reaching ~60% the total population of peptides at the respective peaks (Figure 5). The peptide population with three GalNAc moieties only peaked at ~30%, consistent with rapid conversion beyond three GalNAc to a four GalNAc state for HRT*7 and HRT*15. After the end of the fast-addition phase of the reactions, both T start sites had predominately four GalNAc moieties, plateauing at ~60%.

In contrast, for the two S glycosylation start sites (HRS*9, HRS*11), the second and third glycans were added rapidly before the rate of GalNAc addition slowed down. The glycopeptide population with three GalNAc moieties accumulated to peak ~50% and ~60% for HRS*9 and HRS*11, respectively (Figure 5). These data are consistent with our finding that T residues (T7, T15) are the preferred start sites and that the availability of these T residues likely impacts the rates by which the second and third sites are glycosylated. At the end of the fast-addition phase, HRS*9 had predominately five GalNAc moieties, accounting to ~60% of the total glycopeptide population, and HRS*11 plateaued at four GalNAc moieties, accounting for ~70% the total glycopeptide. This result indicated that more GalNAc residues were added to HRS*9 than to any other start-site glycopeptides, suggesting that initial-site selection could affect final glycan density. The glycopeptide HRS*9, which had the largest diversity of alternative second sites (Figure 4), also had the greatest density of glycans added (Figure 5).

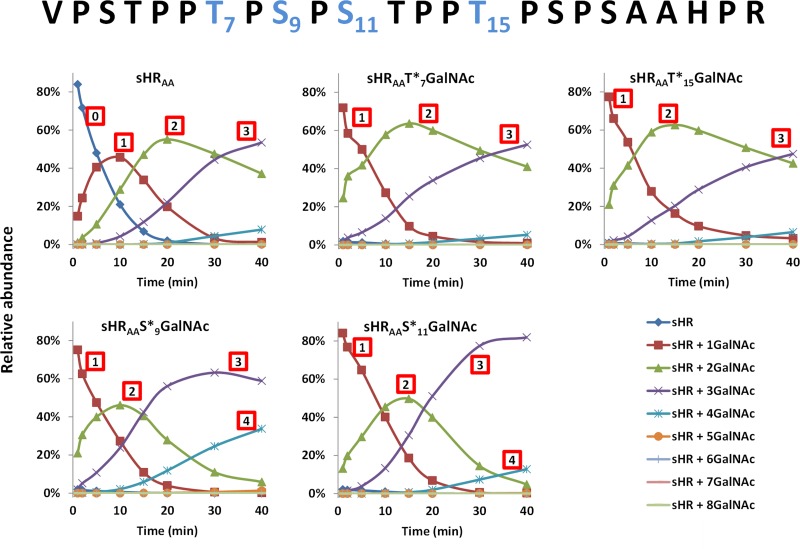

As the final glycan density of HR peptide was highly affected by the lectin domain of GalNAc-T2 (Figure 1), we sought to determine its role in the final densities of glycans added to each first site glycopeptide (HRT*7, HRT*15, HRS*9, and HRS*11) or non-glycosylated HR peptide by reacting with GalNAc-T2 D458H and ΔLD (Figure S5). As expected, the lectin domain mutant GalNAc-T2 D458H and the GalNAc-T2 ΔLD variant, without the lectin domain, did not add as many glycans to first site acceptor GalNAc glycopeptides (Figures 6 and S5). Additionally, glycans were added at a slower rate for both GalNAc-T2 D458H and ΔLD variants compared to wild-type enzyme, demonstrating the role of the lectin domain in increasing the rate of addition to glycopeptides. Both T first-site HR glycopeptides finished the fast-addition phase of the reaction with approximately equal proportions of glycopeptides containing 2 and 3 GalNAc moieties (Figures 6 and S5). Interestingly, both S first site HR glycopeptides exhibited slower addition of GalNAc by both GalNAc-T2 D458H and ΔLD compared to GalNAc-T2. This result suggests that while the lectin domain plays a minor role in second-glycosylation site selection (Figure 4), it increases the rate of GalNAc addition. At the end of the fast-addition phase of the reaction, both HRS*9 and HRS*11 substrates contained predominantly 4 GalNAc moieties. There was more GalNAc added to either S first site glycopeptide than to any T first site glycopeptides. This result further supports the T-motif bias, as the two additional T glycosylation sites are available on each S first-site glycopeptide, but only one additional T site is available on each T first-site glycopeptide. Interestingly, while wild-type GalNAc-T2 finished the fast-addition phase of the HRS*9 and HRS*11 glycosylation with different number of GalNAc moieties attached (5 and 4, respectively), the lectin domain GalNAc-T2 mutants glycosylated both substrate glycopeptides similarly, reaching predominantly three GalNAc moieties per glycopeptide (Figure 6 and summarized in Figure 7B). This observation suggests that the lectin domain is partially responsible for the changes in glycan density imposed by the selection of the first glycosylation site.

Figure 6.

The absence of GalNAc-T2 functional lectin domain affects IgA1 HR glycosylation kinetics and leads to reduction of final glycan density in a first-site-dependent manner: Reaction profiles for first 40 min of GalNAc-T2 D458H with peptide/glycopeptides HRAA, HRAAT7GalNAc, HRAAT15GalNAc, HRAAS9GalNAc, and HRAAS11GalNAc. Relative abundance of each glycoform at each time point is plotted. Top: HRAA sequence with the respective sites of GalNAc attachment for HRAAT7GalNAc, HRAAT15GalNAc, HRAAS9GalNAc, HRAAS11GalNAc shown in blue.

In vitro glycosylation of IgA1 hinge region by GalNAc-T2 closely resembles native IgA1 O-glycosylation

Data from the initial report about ordered addition of GalNAc to IgA1 HR peptide catalyzed by GalNAc-T2 (Iwasaki et al. 2003) do not quite fit with O-glycosylation sites of serum IgA1 (Figure 7C) (Mattu et al. 1998; Takahashi et al. 2012). Using the native IgA1 HR sequence and optimized reaction conditions, the major sites of glycosylation we identified for the first and second attached GalNAc residues closely resemble the sites observed in serum IgA1 (Figure 7C). Small variations may be explained by using a peptide vs. native substrate and additional specific characteristic differences of in vitro vs. the Golgi luminal environment where the enzyme acts on properly folded IgA1. A particular discrepancy is that in our in vitro results, T15 (corresponding to T236 in IgA1) is a dominant site, whereas in vivo it is only ~50% occupied. One explanation may be the proximity of this site to two disulfide bonds connecting the two heavy chains and their HRs that may cause steric hindrance in vivo. Overall, glycan density and GalNAc progressive addition rate correlate well with density of glycans in serum IgA1 HR. These observations suggest that GalNAc-T2 activity assays performed under our in vitro conditions closely approximate native conditions for IgA1 glycosylation. The usual sites of O-glycosylation in serum IgA1 HR are T225, T228, S230, S232, T233, and T236 and the predominant sites of Gal deficiency are S230, T233, and T236 (Figure 7C) (Mattu et al. 1998; Takahashi et al. 2010, 2012). Of the four alternative initial sites of GalNAc addition utilized by GalNAc-T2 (Figure 7), two sites, S230 and T236, are often Gal-deficient in serum IgA1 (Takahashi et al. 2012). Three of the four initial sites of glycosylation, T228, S230, and S232, had corresponding second sites that are sites of potential Gal deficiency, predominantly T236 (Figure 4). Our data revealed that GalNAc-T2 is biased for T236 usage due to the catalytic-domain activity (sequence-recognition motif), although the lectin domain enhanced the catalytic domain specificity (Figure 4). Taken together, these results suggest that a bias to a particular initial site of IgA1 HR glycosylation could increase the likelihood of attachment of GalNAc to a second site that frequently remains Gal-deficient in serum IgA1.

Discussion

It is not well understood how IgA1 clustered O-glycans are consistently added to similar sites with similar frequencies by IgA1-producing cells. This is a critical question because when these glycans are altered, they can present as an autoantigen such as in the autoimmune disease IgAN. Part of the answer relies on the specific properties of glycosylation-initiation steps by the family of GalNAc-Ts, the enzymes that determine both the sites and density of O-glycans. GalNAc-T2 is one of multiple GalNAc-Ts expressed in plasma cells that include also GalNAc-T1, -T3, -T4, -T6 and -T9 (Iwasaki et al. 2003). Some of these GalNAc-T isozymes may be involved in IgA1 HR glycosylation together with GalNAc-T2, including GalNAc-T1, -T3, -T4 and -T11 (Wandall et al. 2007; Pedersen et al. 2011). Our results provide a detailed analysis of the initial steps of clustered O-glycosylation of IgA1 HR by GalNAc-T2. These data reveal a connection of site-specific glycosylation, glycosylation pathway selection, and final glycan density. Furthermore, our results indicated specific mechanisms utilized by the two domains of GalNAc-T2, catalytic and lectin domains, in determining site-specific glycosylation, pathway selection, and glycan density. As multiple GalNAc-T isozymes are likely involved in IgA1 HR glycosylation (Wandall et al. 2007), the methods we utilized in this work can help to differentiate isozyme-specific activities towards IgA1 HR. Finally, with respect to GalNAc attachment, our results clearly show that the initial-site selection can set a course that defines the final glycan composition of IgA1 HR, contributing to a paradigm of how reproducible O-glycosylation can be achieved and altered.

First, we identified four alternative initial sites of glycosylation by GalNAc-T2 in IgA1 HR that included T7, S9, S11 and T15 (Figure 3). Each of these initial sites corresponds well to the glycosylation sites observed in serum IgA1 (Figure 7). Although several studies have demonstrated that GalNAc-Ts can start at alternative sites in mucin-derived peptides and affect the subsequent sites of glycosylation, the effects were largely attributed to individual pathways associated with alternative isozymes rather than multiple pathways specific to a single isozyme(s) (Iida et al. 1999; Kato, Takeuchi, Kanoh et al. 2001; Kato, Takeuchi, Miyahara 2001; Takeuchi et al. 2002). Later, it was demonstrated that GalNAc-T2 could follow multiple pathways of IgA1 O-glycosylation (Iwasaki et al. 2003), but more recent descriptions of native serum IgA1 glycosylation (summarized in Figure 7C) did not fully corroborate the identified pathways. Our results identify four alternative initial sites, thus supporting a model that describes IgA1 HR glycosylation as a semi-ordered process. Furthermore, the results point to an underlying theme that extensive glycosylation of a substrate by a single GalNAc-T isozyme requires promiscuity in peptide-site recognition by the enzyme, rather than following a highly ordered process (see Figures 7 and S8). This promiscuity manifests itself in multiple site-specific glycosylation pathways. A balance between specificity and promiscuity is reflected in relative usage of initial sites of glycosylation, as demonstrated by a ~70% preference for the initialsite of glycosylation at T7 or T15. These sites contain identical surrounding amino acids that conform well to previously identified GalNAc-T2 glycosylation motifs. Still, ~30% of glycosylation occurs at S9 and S11 sites that are more disparate from identified glycosylation motifs (Gerken et al. 2006). Balance between specificity and promiscuity is likely reflected in final site-specific usage of sites for a given peptide. Additional factors play a role, including how preexisting GalNAc residues influence follow-up recognition by the catalytic and lectin domains as well as the presence and activity of other glycosyltransferases that may concurrently be involved in glycosylation (Revoredo et al. 2016).

Evaluation of members of the family of 20 GalNAc-Ts through a variety of in vitro reactions with peptide substrates has made great strides in identifying isozyme-specific traits of different members of the GalNAc-T family (O’Connell et al. 1992; Gerken et al. 2006, 2008, 2011; Kong et al. 2015). Our results add to this knowledge, especially that by using a native amino acid sequence peptide we demonstrated a direct correlation with the sites of glycosylation observed for serum IgA1. The four initial sites we identified for GalNAc-T2 glycosylation of IgA1 HR agree well with prediction algorithms based on the findings of Gerken and colleagues (Figure S4). However, our results do not explain the robust glycosylation of T225 (corresponding to T4 in the HR synthetic peptide) in serum IgA1 (Figure 7), further providing indirect evidence for the role of other GalNAc-T isozymes for “fill-in” activity towards IgA1 HR (Pratt et al. 2004; Revoredo et al. 2016). Residue T4 was most extensively glycosylated as a second site, resulting from the initial glycan addition to S9 or S11, suggesting that rather than being a result of an alternative-isozyme catalytic specificity, T4 glycosylation may result from a lectin-assisted event of another GalNAc-T (Figure 7A).

Results of second site experiments with glycopeptides predominately mirrored initial site experiments, although several other sites were used with a lower frequency. This observation suggests that second site selection is predominately directed by catalytic domain peptide sequence specificity and that the lectin domain helps to target additional sites that would otherwise not be good acceptors. Each initial site did, however, bias the selection of second sites (Figures 4 and 7A), indicating differential GalNAc-T2 site-specificity for different HR (glyco)peptide substrates. Comparative analysis of wild-type GalNAc-T2 and its lectin domain binding mutant revealed two disparate roles for the lectin domain (Figures 4, 7 and S8): i) The lectin domain works concordantly with the catalytic domain to impose order and preference directing the catalytic domain towards the second catalytic domain recognition sites (see Figure 4, peptides HRT*7 and HRT*15). ii) The lectin domain enables the catalytic domain to sample/explore alternative (less abundant) sites. These two distinct activities are co-dependent on the initial-site selection and impact quantitative and kinetic aspects of in vitro time-course reactions (Figures 7, S7, and S8). Our results demonstrated how the fidelity of clustered glycosylation of IgA1, including the final quantitative heterogeneity of O-glycoforms, can be influenced by the initial steps of GalNAc addition. Additionally, our results demonstrated how GalNAc-T isozymes can be differentiated in terms of their activity through quantitative and site-specific analysis of the initial steps and final density of clustered glycans on synthetic peptides. Small differences between isozymes may have in vivo relevance for diseases, such as IgAN, where subtle changes in glycosylation patterns change glycan presentation in an autoantigenic manner.

In the initial time-course plots, we identified a possible role for the lectin domain in the fast-phase portion of GalNAc additions. Not only did the lectin-mutant variants limit the reactions from proceeding to higher density (beyond three GalNAc additions), but they also slowed the consumption of substrates with 1 and 2 GalNAc residues already added relative to the initial addition. Time-course reactions using the glycopeptide starting substrates further confirmed this conclusion and the MS/MS analysis also revealed that the GalNAc-T2 lectin variants had altered pathways of addition. When initiating from T7 (T228) or T15 (T236), the lectin domain promotes order by directing synthesis to the opposite T motif in the tandem repeat. For the impaired or absent lectin domain variants, this order was lessened which must also contribute to the slower consumption of the glycopeptides with 2 and 3 GalNAc additions. Whereas the initial steps are likely driven by the catalytic-domain recognition of amino-acid motifs, the lectin domain helps to target sites that would otherwise not be good acceptors (Figures 7 and S8).

The formation of circulating immune complexes followed by their renal deposition in patients with IgAN is driven by presence of terminal GalNAc on Gal-deficient IgA1 and its recognition by autoantibodies (Novak et al. 2015; Knoppova et al. 2016). Patients with IgAN have elevated serum levels of IgA1 with terminal GalNAc that correlate with serum levels of IgG autoantibodies (Placzek et al. 2018). Initial theories on the origin of this IgA1 glycosylation phenotype proposed that addition of Gal would be impaired due to C1GALT1 reduced expression caused by a COSMC mutation(s). However, IgAN patients do not seem to exhibit mutations in COSMC gene (Malycha et al. 2009), such as those described in some cancers (Ju and Cummings 2005). Alternative hypothesis proposes that reduced expression of C1GALT1/COSMC leads to decreased C1GalT1 activity (Suzuki et al. 2011); although the mechanism is not clear, it involves genetic control (Kiryluk et al. 2017). The data presented here offer a new hypothesis to be tested in the future: Preferential usage of specific first sites by GalNAc-T2, or other GalNAc-T isozymes, enhances production of IgA1 glycoforms with Gal-deficient sites. Specifically, increased content of terminal GalNAc (i.e., Gal-deficient sites) on IgA1 in IgAN can occur due to a difference in the quantitative usage or different sites of glycosylation initiation by a GalNAc-T in addition to a failure to complete the clustered O-glycan biosynthesis (i.e., deficiency in Gal addition).

Conceptually, our results demonstrate the biological implications of multiple initial sites of addition. Through our time-course experiments, we identified a fast rate phase of clustered GalNAc addition. It is likely that the end of the fast phase of GalNAc addition correlates with the point of maximum isomeric diversity. For the GalNAc-T2 clustered activity on the native IgA1 HR, the fast phase ends after three GalNAc residues are added. The predominant O-glycoforms of native IgA1 have at least three O-glycan chains, correlating well with our results. Our data demonstrate that the catalytic and lectin domains each have a role in this initial fast phase (Figures 4–6 and S5). Our data do not directly address how GalNAc addition may decrease galactosylation in IgAN. However, it is possible that an elevated number of GalNAc residues in IgA1 HR may reduce Gal content, especially if C1GalT1 activity would not increase proportionally. Moreover, neighboring glycosylation sites as well as amino-acid-sequence context affect C1GalT1 activity (Gerken et al. 1998; Gerken 2004); both mechanisms may thus increase Gal deficiency in IgAN.

Figures 7 and S8 summarize identified features of GalNAc-T2 that either expand the number of pathways explored or limit them. Initially in the reaction isomeric diversity is low as there is only a limited set of initial glycan positions associated with catalytic domain sequence recognition and some of these are preferred over others. The multiple initial glycan positions create a combination of potential pathways that increase the probability of dense glycosylation. At some point, while sampling multiple pathways, a maximal isomer diversity is reached as the weighted pathways start converging to a final reproducible quantitative heterogeneity (Figures S7 and S8). Interestingly, glycosylation events as early as initial GalNAc attachment can bias the pathways traversed in a manner that changes final GalNAc sites and density (Figures 7 and S8). Probability modeling of this multisite semi-ordered mechanism versus an ordered site preference model provides support for multiple pathways being the optimal way to achieve dense glycosylation for a single GalNAc-T isozyme (Figures S7 and S8).

These results provide new insight into the mechanisms of clustered O-glycan synthesis, namely the specific features of GalNAc-Ts and their substrates that either increase or decrease promiscuity toward the substrate(s). The methods described here will be useful for further differentiating GalNAc-T isozymes at the catalytic- and lectin-domain levels through the quantitative analysis of the order of GalNAc incorporation and the final glycan density. Understanding details of substrate glycosylation by each GalNAc-T isozyme may explain how combinations of these enzymes can act in a coordinated fashion in vivo. For example, in vitro reactions of combinations of different GalNAc-Ts would provide kinetic and site-specific profiles that could be modeled and then correlated with glycosylation profiles of native glycoproteins with clustered O-glycans.

Material and methods

GalNAc-T2 cloning, expression, and purification

Cloning: The GalNAc-T2 coding region for amino acids 52-571 of the GALNT2 gene was PCR amplified from cDNA prepared from Freestyle 293-F cells with the forward and reverse gene-specific primers forward 1 and reverse 1 (see below) and cloned using Gibson assembly into pOPING plasmid cut with KpnI and PmeI restriction enzymes (Berrow et al. 2007).

Primers:

Forward 1: GCGTAGCTGAAACCGGCAAAAAGAAAGACCTTCATCAC

Forward 2: TAACTGCCTCCACACTTTGGGACAC

Reverse 1: GTGATGGTGATGTTTCTGCTGCAGGTTGAGCGTG

Reverse 2: GTGATGGTGATGTTTTAACTCTGGATAGACATTTTCAAGGTACC

Reverse 3: GTTCCCTGCTGCAAGGCC

The resultant plasmid was designated T2 pOPING. The lectin domain deleted construct from amino acids 52-436, T2 ΔLD pOPING, was subcloned from T2 pOPING using the primer pair forward 1 and reverse 2. Site-directed mutagenesis (changing D458 to H in the lectin domain) was performed in T2 pcDNA3.1 using the primer pair forward 2 and reverse 3. The resultant mutant was subcloned into pOPING plasmid to form T2-D458H pOPING. Insets in all constructs were confirmed by Sanger DNA sequencing.

Expression: Mammalian Expi293F cells were transiently transfected with the expression plasmids using the Expi293 expression system (ThermoFisher). The proteins were secreted into the culture medium as a result of pOPING derived secretion signal. Typical expression was performed in 80-mL cultures and the serum-free culture medium was harvested 72 h post-transfection by removing cells by centrifugation (3000 rcf for 10 min), followed by 0.2 μm filtration.

Purification: Adapting buffer (250 mM cacodylate pH 6.6, 500 mM NaCl, 100 mM imidazole, with 0.05% Tween-20) was added to filtered media with secreted recombinant GalNAc-T2 at a ratio of 1:9 v/v. One mL bed volume of Qiagen Ni-NTA agarose was added to the media with adapting buffer and the beads were slowly agitated overnight at 4°C. Ni-NTA beads were collected and washed once with six column volumes of binding buffer (25 mM cacodylate pH 6.6, 10 mM imidazole, 0.05% Tween-20) followed by six column volumes of wash buffer (25 mM cacodylate pH 6.6, 20 mM imidazole, 0.05% Tween-20). Bound enzyme was eluted three times with three column volumes using elution buffer (25 mM cacodylate pH 6.6, 200 mM imidazole, 0.05% Tween-20). All fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by protein stain with Coomassie brilliant blue. The fractions containing bulk of enzyme were pooled (usually the first two-elution volumes). Pooled fractions were concentrated, and buffer was exchanged into 25 mM cacodylate buffer pH 6.6, 0.05% Tween-20. The resultant protein preparation was mixed with equal volume of sterile 80% glycerol in water and stored at −20°C. Typical enzyme preparations had > 95% purity, appearing as a single band on SDS-PAGE with Coomassie-blue staining, and concentrations of enzyme stocks ranged between 0.5–4.0 mg/mL with yields between 5 and 50 mg of protein per 1 L of culture medium.

Glycopeptide synthesis

Peptides were prepared using a standard, double-addition, FMOC, solid-phase peptide synthesis strategy on the Prelude system (Gyros Protein Technologies, Sweden). 4-(2′,4′-Dimethoxyphenyl-Fmoc-aminmethyl)-phenoxyacetamido-methylbenzhydryl amine resin (Rink amide MBHA resin, Anaspec) is swelled in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, Fisher) and methylene chloride (DCM, Fisher) to increase surface area availability for bonding. Using a double-addition FMOC strategy, the N-terminal FMOC on the growing peptide chain is deprotected with 0.8 M piperidine (Fisher) in DMF for 2.5 min, then the following amino acid (200 mM) to be added to the N-terminus is activated with 0.4 M O-(1H-6-Chlorobenzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HCTU, Anaspec) in DMF for nucleophilic attack of the N-terminal peptidyl-resin. Next, 800 mM 4-Methylmorpholine (NMM, Fisher) in DMF is added, and the peptidyl-resin, HCTU, NMM slurry is mixed for 30 min followed by 4 × 30 s DMF washes. Glycosylated amino acid precursors were employed to control site-specific GalNAc addition to target T or S amino acids (Sussex Research). These were incorporated into synthesis in the same manner as un-glycosylated amino acids (Anaspec). Peptidyl resin was cleaved using 88% TFA, 5% water, 5% phenol, and 2% triisopropylsilane. The resin was filtered by hand using the Prelude reaction vessels away from the cleavage mix, which was then cold-ether precipitated and centrifuged at 14,000 g to pellet the resin-cleaved, crude peptide. Peptides were lyophilized, then deacetylaled in 10% sodium methoxide, 90% methanol for 10 min, then re-lyophilized. Crude glycopeptide preparations were resuspended in 80% water/20% acetonitrile and purified using a Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 column (Agilent) on a 1260 Infinity HPLC (Agilent) with a 5-60% acetonitrile gradient. Glycopeptide mass was confirmed by MALDI-MS. Peptide concentration was determined by NMR comparing approximated glycopeptide concentrations to known standards and further verified by dry weight and UV spectroscopic means.

GalNAc-T2 reactions

Typical GalNAc-T2 reactions were performed in 25 μL volumes consisting of 25 mM cacodylate buffer pH 6.6, 50 mM MnCl2, 250–500 μM UDP-GalNAc, 20 μM acceptor peptide, and 5–25 ng enzyme. Enzyme was diluted to working concentration in cold 0.01% Tween-20 just prior to reaction initiation. Reactions were quenched, in whole or in aliquots, by either boiling for 10 min or by addition of an equal volume of 25 mM EDTA solution. For time-course experiments, reactions were scaled-up appropriately to accommodate 2.5-μL sampling (quenched by adding 2.5 μL 25 mM EDTA) for the desired number of time points.

LC-MS analysis of GalNAc-T2 reaction products

LC-MS methods: Reaction products were diluted to 1-μM (glyco)peptide concentration in 0.1% formic acid (FA). A volume of 5–10 μL of diluted reactions were separated on a Jupiter 5 μM 300 Å 11 cm × 100 μM column packed in fused silica pulled tip. Separations were performed using Dionex 3000 nanoLC system with a 16 min linear gradient from 6% A (2.5% acetonitrile 0.1% FA) to 17% B (97.5% acetonitrile 0.1% FA) at a flow rate of 650 nL/min. High-resolution MS analysis was performed using an Orbitrap Velos Pro and fragmentation with either collision induced dissociation (CID) or electron transfer dissociation (ETD) for the top 10 ions observed per scan was analyzed in the ion trap. Site-specific GalNAc analysis: To enhance ETD fragmentation efficiency, ions below 4+ charge state were excluded allowing more thorough fragmentation of higher charge state ions. ETD spectra were manually interpreted using ThermoFisher QualBrowser software. Relative quantification of GalNAc glycoforms: Relative quantification of glycoforms for kinetic analysis was performed in Pinnacle software that integrates peak area for extracted ion chromatograms of reaction products. Retention times were manually adjusted in Pinnacle after initial analysis.

ISOGlyP analysis of IgA1 HR

The IgA1 HR amino-acid sequence 222VPSTPPTPSPSTPPTPSPSCCHPR245 matching synthetic HR peptide sequence was submitted in ISOGlyP web tool (http://isoglyp.utep.edu/index.php) with default settings and all GalNAc-T isozymes selected. ISOGlyP is a web tool designed to predict relative rates of glycosylation by GalNAc-T enzymes at isozyme specific resolution (Gerken et al. 2006, 2008, 2011; Perrine et al. 2009). After obtaining enhancement values, enhancement values were unchanged, reduced by a factor of 10 per ISOGlyP suggestion, or decreased by a factor of 3, based on our experimental evidence of site usage.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- IgAN

IgA nephropathy

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography mass spectrometry

- ETD

electron transfer dissociation

- HR

hinge-region

- CID

collision induced dissociation

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

Funding

This study was supported in part by grants from National Institutes of Health (DK109599, GM098539, DK078244, DK082753) and by a gift from the IGA Nephropathy Foundation of America. MR was supported in part by grants LH15263 from Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sport, Czech Republic. pOPING was a gift from Ray Owens (Addgene plasmid # 26046).

Conflict of interest statement

WJP, JN and MBR are co-founders of Reliant Glycosciences, LLC.

References

- Baenziger J, Kornfeld S. 1974. Structure of the carbohydrate units of IgA1 immunoglobulin. II. Structure of the O-glycosidically linked oligosaccharide units. J Biol Chem. 249:7270–7281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett EP, Mandel U, Clausen H, Gerken TA, Fritz TA, Tabak LA. 2012. Control of mucin-type O-glycosylation: a classification of the polypeptide GalNAc-transferase gene family. Glycobiology. 22:736–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrow NS, Alderton D, Sainsbury S, Nettleship J, Assenberg R, Rahman N, Stuart DI, Owens RJ. 2007. A versatile ligation-independent cloning method suitable for high-throughput expression screening applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clausen H, Bennett EP. 1996. A family of UDP-GalNAc: polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyl-transferases control the initiation of mucin-type O-linked glycosylation. Glycobiology. 6:635–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field MC, Dwek RA, Edge CJ, Rademacher TW. 1989. O-linked oligosaccharides from human serum immunoglobulin A1. Biochem Soc Trans. 17:1034–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franc V, Rehulka P, Raus M, Stulik J, Novak J, Renfrow MB, Sebela M. 2013. Elucidating heterogeneity of IgA1 hinge-region O-glycosylation by use of MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry: role of cysteine alkylation during sample processing. J Proteomics. 92:299–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz TA, Hurley JH, Trinh LB, Shiloach J, Tabak LA. 2004. The beginnings of mucin biosynthesis: the crystal structure of UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide α-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-T1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 101:15307–15312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz TA, Raman J, Tabak LA. 2006. Dynamic association between the catalytic and lectin domains of human UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide alpha-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-2. J Biol Chem. 281:8613–8619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerken TA. 2004. Kinetic modeling confirms the biosynthesis of mucin core 1 (β-Gal(1-3) α-GalNAc-O-Ser/Thr) O-glycan structures are modulated by neighboring glycosylation effects. Biochemistry. 43:4137–4142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerken TA, Gilmore M, Zhang J. 2002. Determination of the site-specific oligosaccharide distribution of the O-glycans attached to the porcine submaxillary mucin tandem repeat. Further evidence for the modulation of O-glycans side chain structures by peptide sequence. J Biol Chem. 277:7736–7751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerken TA, Jamison O, Perrine CL, Collette JC, Moinova H, Ravi L, Markowitz SD, Shen W, Patel H, Tabak LA. 2011. Emerging paradigms for the initiation of mucin-type protein O-glycosylation by the polypeptide GalNAc transferase family of glycosyltransferases. J Biol Chem. 286:14493–14507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerken TA, Owens CL, Pasumarthy M. 1998. Site-specific core 1 O-glycosylation pattern of the porcine submaxillary gland mucin tandem repeat. Evidence for the modulation of glycan length by peptide sequence. J Biol Chem. 273:26580–26588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerken TA, Raman J, Fritz TA, Jamison O. 2006. Identification of common and unique peptide substrate preferences for the UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide alpha-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases T1 and T2 derived from oriented random peptide substrates. J Biol Chem. 281:32403–32416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerken TA, Revoredo L, Thome JJ, Tabak LA, Vester-Christensen MB, Clausen H, Gahlay GK, Jarvis DL, Johnson RW, Moniz HA et al. 2013. The lectin domain of the polypeptide GalNAc transferase family of glycosyltransferases (ppGalNAc Ts) acts as a switch directing glycopeptide substrate glycosylation in an N- or C-terminal direction, further controlling mucin type O-glycosylation. J Biol Chem. 288:19900–19914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerken TA, Ten Hagen KG, Jamison O. 2008. Conservation of peptide acceptor preferences between Drosophila and mammalian polypeptide-GalNAc transferase ortholog pairs. Glycobiology. 18:861–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen FK, Van Wuyckhuyse B, Tabak LA. 1993. Purification, cloning, and expression of a bovine UDP-GalNAc: polypeptide N-acetyl-galactosaminyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 268:18960–18965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanisch FG. 2001. O-glycosylation of the mucin type. Biol Chem. 382:143–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida S, Takeuchi H, Hassan H, Clausen H, Irimura T. 1999. Incorporation of N-acetylgalactosamine into consecutive threonine residues in MUC2 tandem repeat by recombinant human N-acetyl-D-galactosamine transferase-T1, T2 and T3. FEBS Lett. 449:230–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida S, Takeuchi H, Kato K, Yamamoto K, Irimura T. 2000. Order and maximum incorporation of N-acetyl-D-galactosamine into threonine residues of MUC2 core peptide with microsome fraction of human-colon-carcinoma LS174T cells. Biochem J. 347:535–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki H, Zhang Y, Tachibana K, Gotoh M, Kikuchi N, Kwon YD, Togayachi A, Kudo T, Kubota T, Narimatsu H. 2003. Initiation of O-glycan synthesis in IgA1 hinge region is determined by a single enzyme, UDP-N-acetyl-α-D-galactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 2. J Biol Chem. 278:5613–5621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji S, Samara NL, Revoredo L, Zhang L, Tran DT, Muirhead K, Tabak LA, Ten Hagen KG. 2018. A molecular switch orchestrates enzyme specificity and secretory granule morphology. Nat Commun. 9:3508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju T, Cummings RD. 2005. Protein glycosylation: chaperone mutation in Tn syndrome. Nature. 437:1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K, Takeuchi H, Kanoh A, Mandel U, Hassan H, Clausen H, Irimura T. 2001. N-acetylgalactosamine incorporation into a peptide containing consecutive threonine residues by UDP-N-acetyl-D-galactosaminide:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases. Glycobiology. 11:821–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K, Takeuchi H, Miyahara N, Kanoh A, Hassan H, Clausen H, Irimura T. 2001. Distinct orders of GalNAc incorporation into a peptide with consecutive threonines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 287:110–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiryluk K, Li Y, Moldoveanu Z, Suzuki H, Reily C, Hou P, Xie J, Mladkova N, Prakash S, Fischman C et al. 2017. GWAS for serum galactose-deficient IgA1 implicates critical genes of the O-glycosylation pathway. PLoS Genet. 13:e1006609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoppova B, Reily C, Maillard N, Rizk DV, Moldoveanu Z, Mestecky J, Raska M, Renfrow MB, Julian BA, Novak J. 2016. The origin and activities of IgA1-containing immune complexes in IgA nephropathy. Front Immunol. 7:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Y, Joshi HJ, Schjoldager KT, Madsen TD, Gerken TA, Vester-Christensen MB, Wandall HH, Bennett EP, Levery SB, Vakhrushev SY et al. 2015. Probing polypeptide GalNAc-transferase isoform substrate specificities by in vitro analysis. Glycobiology. 25:55–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai KN, Tang SC, Schena FP, Novak J, Tomino Y, Fogo AB, Glassock RJ. 2016. IgA nephropathy. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2:16001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lira-Navarrete E, de Las Rivas M, Companon I, Pallares MC, Kong Y, Iglesias-Fernandez J, Bernardes GJ, Peregrina JM, Rovira C, Bernado P et al. 2015. Dynamic interplay between catalytic and lectin domains of GalNAc-transferases modulates protein O-glycosylation. Nat Commun. 6:6937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz V, Ditamo Y, Cejas RB, Carrizo ME, Bennett EP, Clausen H, Nores GA, Irazoqui FJ. 2016. Extrinsic functions of lectin domains in O-N-Acetylgalactosamine glycan biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 291:25339–25350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malycha F, Eggermann T, Hristov M, Schena FP, Mertens PR, Zerres K, Floege J, Eitner F. 2009. No evidence for a role of cosmc-chaperone mutations in European IgA nephropathy patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 24:321–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattu TS, Pleass RJ, Willis AC, Kilian M, Wormald MR, Lellouch AC, Rudd PM, Woof JM, Dwek RA. 1998. The glycosylation and structure of human serum IgA1, Fab, and Fc regions and the role of N-glycosylation on Fcα receptor interactions. J Biol Chem. 273:2260–2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mestecky J, Tomana M, Crowley-Nowick PA, Moldoveanu Z, Julian BA, Jackson S. 1993. Defective galactosylation and clearance of IgA1 molecules as a possible etiopathogenic factor in IgA nephropathy. Contrib Nephrol. 104:172–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson T, Au CE, Bergeron JJ. 2009. Sorting out glycosylation enzymes in the Golgi apparatus. FEBS Lett. 583:3764–3769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak J, Julian BA, Mestecky J, Renfrow MB. 2012. Glycosylation of IgA1 and pathogenesis of IgA nephropathy. Semin Immunopathol. 34:365–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak J, Moldoveanu Z, Renfrow MB, Yanagihara T, Suzuki H, Raska M, Hall S, Brown R, Huang WQ, Goepfert A et al. 2007. IgA nephropathy and Henoch-Schoenlein purpura nephritis: aberrant glycosylation of IgA1, formation of IgA1-containing immune complexes, and activation of mesangial cells. Contrib Nephrol. 157:134–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak J, Rizk D, Takahashi K, Zhang X, Bian Q, Ueda H, Ueda Y, Reily C, Lai LY, Hao C et al. 2015. New insights into the pathogenesis of IgA nephropathy. Kidney Dis (Basel). 1:8–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak J, Takahashi K, Suzuki H, Reily C, Stewart T, Ueda H, Yamada K, Moldoveanu Z, Hastings M, Wyatt C et al. 2016. Heterogeneity of aberrant O-glycosylation of IgA1 in IgA nephropathy In: Tomino Y, editor. Pathogenesis and Treatment in IgA Nephropathy. Tokyo, Japan: Springer Japan; p. 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Novak J, Tomana M, Kilian M, Coward L, Kulhavy R, Barnes S, Mestecky J. 2000. Heterogeneity of O-glycosylation in the hinge region of human IgA1. Mol Immunol. 37:1047–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell BC, Hagen FK, Tabak LA. 1992. The influence of flanking sequence on the O-glycosylation of threonine in vitro. J Biol Chem. 267:25010–25018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paroutis P, Touret N, Grinstein S. 2004. The pH of the secretory pathway: measurement, determinants, and regulation. Physiology (Bethesda). 19:207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen JW, Bennett EP, Schjoldager KT, Meldal M, Holmer AP, Blixt O, Clo E, Levery SB, Clausen H, Wandall HH. 2011. Lectin domains of polypeptide GalNAc transferases exhibit glycopeptide binding specificity. J Biol Chem. 286:32684–32696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrine CL, Ganguli A, Wu P, Bertozzi CR, Fritz TA, Raman J, Tabak LA, Gerken TA. 2009. Glycopeptide-preferring polypeptide GalNAc transferase 10 (ppGalNAc T10), involved in mucin-type O-glycosylation, has a unique GalNAc-O-Ser/Thr-binding site in its catalytic domain not found in ppGalNAc T1 or T2. J Biol Chem. 284:20387–20397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Placzek WJ, Yanagawa H, Makita Y, Renfrow MB, Julian BA, Rizk DV, Suzuki Y, Novak J, Suzuki H. 2018. Serum galactose-deficient-IgA1 and IgG autoantibodies correlate in patients with IgA nephropathy. PLoS One. 13:e0190967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt MR, Hang HC, Ten Hagen KG, Rarick J, Gerken TA, Tabak LA, Bertozzi CR. 2004. Deconvoluting the functions of polypeptide N-α-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase family members by glycopeptide substrate profiling. Chem Biol. 11:1009–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman J, Fritz TA, Gerken TA, Jamison O, Live D, Liu M, Tabak LA. 2008. The catalytic and lectin domains of UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide α-N-Acetylgalactosaminyltransferase function in concert to direct glycosylation site selection. J Biol Chem. 283:22942–22951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renfrow MB, Cooper HJ, Tomana M, Kulhavy R, Hiki Y, Toma K, Emmett MR, Mestecky J, Marshall AG, Novak J. 2005. Determination of aberrant O-glycosylation in the IgA1 hinge region by electron capture dissociation fourier transform-ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. J Biol Chem. 280:19136–19145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renfrow MB, Mackay CL, Chalmers MJ, Julian BA, Mestecky J, Kilian M, Poulsen K, Emmett MR, Marshall AG, Novak J. 2007. Analysis of O-glycan heterogeneity in IgA1 myeloma proteins by Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry: implications for IgA nephropathy. Anal Bioanal Chem. 389:1397–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revoredo L, Wang S, Bennett EP, Clausen H, Moremen KW, Jarvis DL, Ten Hagen KG, Tabak LA, Gerken TA. 2016. Mucin-type O-glycosylation is controlled by short- and long-range glycopeptide substrate recognition that varies among members of the polypeptide GalNAc transferase family. Glycobiology. 26:360–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas ML, Lira-Navarrete E, Daniel EJP, Companon I, Coelho H, Diniz A, Jimenez-Barbero J, Peregrina JM, Clausen H, Corzana F et al. 2017. The interdomain flexible linker of the polypeptide GalNAc transferases dictates their long-range glycosylation preferences. Nat Commun. 8:1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Fan R, Zhang Z, Brown R, Hall S, Julian BA, Chatham WW, Suzuki Y, Wyatt RJ, Moldoveanu Z et al. 2009. Aberrantly glycosylated IgA1 in IgA nephropathy patients is recognized by IgG antibodies with restricted heterogeneity. J Clin Invest. 119:1668–1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Kiryluk K, Novak J, Moldoveanu Z, Herr AB, Renfrow MB, Wyatt RJ, Scolari F, Mestecky J, Gharavi AG et al. 2011. The pathophysiology of IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 22:1795–1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Smith AD, Poulsen K, Kilian M, Julian BA, Mestecky J, Novak J, Renfrow MB. 2012. Naturally occurring structural isomers in serum IgA1 O-glycosylation. J Proteome Res. 11:692–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Wall SB, Suzuki H, Smith AD, Hall S, Poulsen K, Kilian M, Mobley JA, Julian BA, Mestecky J et al. 2010. Clustered O-glycans of IgA1: defining macro- and microheterogeneity by use of electron capture/transfer dissociation. Mol Cell Proteomics. 9:2545–2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi H, Kato K, Hassan H, Clausen H, Irimura T. 2002. O-GalNAc incorporation into a cluster acceptor site of three consecutive threonines. Eur J Biochem. 269:6173–6183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ten Hagen KG, Fritz TA, Tabak LA. 2003. All in the family: the UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases. Glycobiology. 13:1R–16R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomana M, Niedermeier W, Mestecky J, Skvaril F. 1976. The differences in carbohydrate composition between the subclasses of IgA immunoglobulins. Immunochemistry. 13:325–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]