Abstract

This survey study of statewide California hospitals evaluates the prevalence and institutional characteristics of hospitals and health systems that have either implemented or opted out of the state’s End of Life Option Act.

The End of Life Option Act (EOLOA) allows terminally ill adult Californians to request a prescription for medication to hasten death under some conditions.1,2 No clinician or health system is required to participate in the EOLOA. While patient access to aid in dying is influenced by how health care organizations implement the law,3 the prevalence of hospitals and health systems opting out is unknown.

Methods

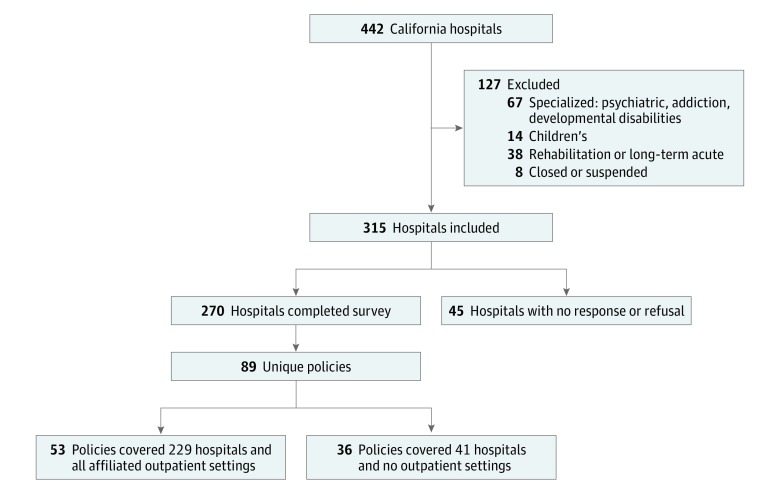

We surveyed California hospitals from September 2017 to March 2018. Although the EOLOA is not designed to be implemented in hospitals, hospitals often are central to health care networks, and health system policies may cover physicians in affiliated settings. We constructed the universe of California hospitals using the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development data4 and excluded children’s, rehabilitation, long-term acute care, and psychiatric hospitals (Figure). All aspects of this study were considered and approved by the IRB, which determined that this study was not human-participant research, and thus consent was waived. Data analysis was conducted from April to August 2018.

Figure. Hospital Sample.

Flowchart of California hospitals excluded and included in study.

Our survey asked whether a hospital had an EOLOA policy and to whom it applied: “Has your organization created any policies about the End of Life Option Act? [yes, no, unsure],” and “Do the policies apply to just your hospital or all of [health system name]? [single hospital, all of health system, unsure].” The interviewer then clarified whether responses included outpatient clinics. Survey responses were collected anonymously by telephone from the hospital representative most knowledgeable about the institution’s implementation of EOLOA. The survey and Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development data were merged to compute bivariate associations between EOLOA policy, hospital characteristics, and number of discharges in 2016.

Results

Of 315 California hospitals, we obtained survey responses for 270 (86%). Nonresponding hospitals were more likely to be rural and for-profit, and less likely to be part of a hospital system. The responding 270 hospitals were covered by 89 unique policies. Fifty-three EOLOA policies (among 229 hospitals) applied to all health system inpatient and outpatient facilities. In contrast, 36 policies applied to 41 hospitals, but offered no guidance for outpatient locations (Figure).

Of the 270 hospitals, 235 (87%) had a formal policy for the EOLOA. Overall, 106 (39%) hospitals permitted physicians to write EOLOA prescriptions: 97 had a formal EOLOA policy and 9 did not. These hospitals accounted for 42% (1 289 236) of hospital discharges in 2016. Of the 164 (61%) hospitals forbidding physicians to write prescriptions under the EOLOA, 138 hospitals had formal policies explicitly prohibiting EOLOA prescribing, and an additional 26 hospitals had no written policy. Hospitals opting out of the EOLOA accounted for 48% (1 501 452) of hospital discharges.

Association of hospital characteristics with stance on the EOLOA is detailed in the Table. Because some hospitals shared policies, we also analyzed these factors at the level of the policy (35 policies permitting vs 54 policies prohibiting the EOLOA). Hospital policies permitting the EOLOA were less likely to be religiously affiliated (3% [n = 1] vs 20% [n = 11]; P = .02), more likely to be nonprofit (71% [n = 25] vs 44% [n = 24]; P = .01), and more likely to offer palliative care (86% [n = 30] vs 67% [n = 36]; P = .05), EOLOA training to physicians (83% [n = 29] vs 41% [n = 22]; P < .001), and information for patients (57% [n = 20] vs 30% [n = 16]; P = .01).

Table. Hospital Participation in the EOLOA.

| Characteristic | Permits EOLOA, No. (%) (n = 106) |

Does Not Permit EOLOA, No. (%) (n = 164) |

|---|---|---|

| Religious affiliation | 2 (2) | 70 (43) |

| Teaching hospital | 22 (21) | 6 (4) |

| Rural hospital | 10 (10) | 29 (18) |

| Hospital systema | 57 (54) | 134 (82) |

| Large hospital (≥500 beds) | 9 (9) | 13 (8) |

| Nonprofit status | 91(86) | 93 (57) |

| Serious illness services on site | ||

| Palliative care | 101 (95) | 127 (77) |

| Spiritual support—patients | 104 (98) | 154 (94) |

| Bereavement support—families | 93 (88) | 113 (69) |

| EOLOA resources | ||

| Have EOLOA policy | 97 (92) | 138 (84) |

| Training for physicians | 99 (93) | 103 (63) |

| Information for patients | 53 (50) | 25 (15) |

Abbreviation: EOLOA, End of Life Option Act.

Hospital system defined as 3 or more hospitals.

Discussion

About 18 months after implementation of the EOLOA, most hospitals in California had an EOLOA policy, and the majority prohibited physicians from participating while under the organization’s purview. The preponderance of restrictive policies likely affects the availability of the EOLOA for a substantial number of Californians. Of the 164 hospitals that prohibit prescriptions under the EOLOA, 134 (82%) also prohibit prescriptions in affiliated outpatient settings. More research is needed on these settings and physicians’ practices.

This study has limitations, including its focus on hospitals and not physicians, lower response rates in rural areas, and imprecision concerning the policies of nonhospital clinics. However, this survey shows that hospitals and health systems that allowed the EOLOA were more likely to offer palliative and bereavement services than those hospitals prohibiting aid in dying. This suggests that where the EOLOA is permitted, it is not as a replacement for, but a complement to, existing end-of-life services.

References

- 1.Mishra R. Implementing California’s law on assisted dying. Hastings Cent Rep. 2017;47(2):7-8. doi: 10.1002/hast.682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eggman S. Assembly Bill No. 15: End of Life. 2016. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201520162AB15. Accessed September 1, 2018.

- 3.Harman SM, Magnus D. Early experience with the California End of Life Option Act: balancing institutional participation and physician conscientious objection. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):907-908. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hospital Annual Utilization Data; Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. https://oshpd.ca.gov/data-and-reports/healthcare-utilization/hospital-utilization/#complete. Published 2016. Accessed September 2017. [Google Scholar]