Key Points

Question

Which treatment-related complications are associated with inpatient admission and financial burden among patients with cancer presenting to emergency departments?

Findings

In this cohort study analyzing the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample from 2006 to 2015, nearly 1.5 million emergency department visits were associated with complications from systemic therapy or radiotherapy. Sepsis, pneumonia, and acute kidney injury were associated with inpatient admission; sepsis, anemia, and neutropenia incurred the highest financial charges.

Meaning

Complications related to cancer therapy result in a substantial number of emergency department visits per year; further study of these complications can help health care professionals better manage them in the outpatient setting.

Abstract

Importance

Systemic therapy and radiotherapy can be associated with acute complications that may require emergent care. However, there are limited data characterizing complications and the financial burden of cancer therapy that are treated in emergency departments (EDs) in the United States.

Objectives

To estimate the incidence of treatment-related complications of systemic therapy or radiotherapy, examine factors associated with inpatient admission, and investigate the overall financial burden.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A retrospective analysis of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Nationwide Emergency Department Sample was performed. Between January 2006 and December 2015, there was a weighted total of 1.3 billion ED visits; of these, 1.5 million were related to a complication of systemic therapy or radiotherapy for cancer. Data analysis was conducted from February 22 to December 23, 2018. External cause of injury codes, Clinical Classifications Software, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification, and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), Clinical Modification codes were used to identify patients with complications of systemic therapy or radiotherapy.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Patterns in treatment-related complications, patient- and hospital-related factors associated with inpatient admission, and median and total charges for treatment-related complications were the main outcomes.

Results

Of the 1.5 million ED visits included in the analysis, 53.2% of patients were female and mean age was 63.3 years. Treatment-related ED visits increased by a rate of 10.8% per year compared with 2.0% for overall ED visits. Among ED visits, 90.9% resulted in inpatient admission to the hospital and 4.9% resulted in death during hospitalization. Neutropenia (136 167 [8.9%]), sepsis (128 171 [8.4%]), and anemia (117 557 [7.7%]) were both the most common and costliest (neutropenia: $5.52 billion; sepsis: $11.21 billion; and anemia: $6.78 billion) complications diagnosed on presentation to EDs; sepsis (odds ratio [OR], 21.00; 95% CI, 14.61-30.20), pneumonia (OR, 9.73; 95% CI, 8.08-11.73), and acute kidney injury (OR, 9.60; 95% CI, 7.77-11.85) were associated with inpatient admission. Costs related to the top 10 most common complications totaled $38 billion and comprised 48% of the total financial burden of the study cohort.

Conclusions and Relevance

Emergency department visits for complications of systemic therapy or radiotherapy increased at a 5.5-fold higher rate over 10 years compared with overall ED visits. Neutropenia, sepsis, and anemia appear to be the most common complications; sepsis, pneumonia, and acute kidney injury appear to be associated with the highest rates of inpatient admission. These complications suggest that significant charges are incurred on ED visits.

This cohort study of 1.5 million ED visits examines rates, costs, and outcomes of emergency department visits by patients with cancer who are undergoing chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

Introduction

Each year, approximately 650 000 patients with cancer in the United States receive systemic therapy or radiotherapy, with 180 000 patients receiving both.1 Systemic therapy and radiotherapy can provide substantial benefit for many patients, but these treatments are also associated with a risk of serious complications.2,3 Although many of these adverse effects can be managed in the outpatient setting, some are severe enough to require treatment in a hospital. Multiple studies have characterized hospitalizations and admissions for patients with cancer in general4,5,6,7,8,9 as well as those receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy.10,11,12 Common presenting diagnoses in emergency departments (EDs) among patients receiving treatment include infection, febrile neutropenia, and anemia. Recognizing the magnitude of this problem, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services have instituted multiple measures, including the Oncology Care Model and the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act, to curb cost and spending in health care and oncologic practice.13 Understanding the diversity of ED visits according to cancer and type of complication will be necessary for building an oncology care model that reflects the reality of cancer care.

Most studies of oncologic-based ED visits have limited analyses of subsequent inpatient admissions. A recent report on cancer-related ED visits found that 60% of the visits resulted in a hospitalization.8 Hospitalizations for treatment-related complications, in particular, carry a high financial burden in the United States health care system. A 2007 MedStat report found that the average cost per ED visit for a chemotherapy-related complication was approximately $800, while an inpatient admission was $22 000.14 Furthermore, hospitalizations can lead to delays in cancer treatment that might affect the patient’s overall response to therapy.5 Hence, greater clarity regarding not only the frequency of cancer treatment–related complications that result in an ED visit but also the associated probability of admission for each complication could inform clinical and policy interventions.

To our knowledge, no study has examined ED visits due to complications of cancer treatment on a national level. This national analysis of complications resulting in ED visits and hospitalizations may help clinicians address these problems in the outpatient setting, thereby possibly decreasing the frequency of ED visits and curbing patient costs. This study describes trends in ED visits related to complications of cancer therapy and examines factors associated with inpatient admission. The overall financial burden of treatment-related complications is also investigated.

Methods

Study Sample and Covariates

This study used the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS) published by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. NEDS is the largest all-payer ED database in the United States, yielding approximately 25 million to 35 million ED visits each year across more than 950 hospitals in 34 states. It represents a 20% stratified sample of US hospital-based EDs. Each ED visit is given a discharge weight so that a national estimate may be obtained. These weights are assigned by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project during the sampling process based on ratios of total ED visits to ED visits sampled in NEDS. All diagnoses reported in NEDS were based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) system until September 30, 2015, after which the Tenth Revision (ICD-10-CM) was used. This study was granted an institutional review board exemption by the Yale Human Investigations Committee. Informed consent was waived because the study was retrospective and data were deidentified.

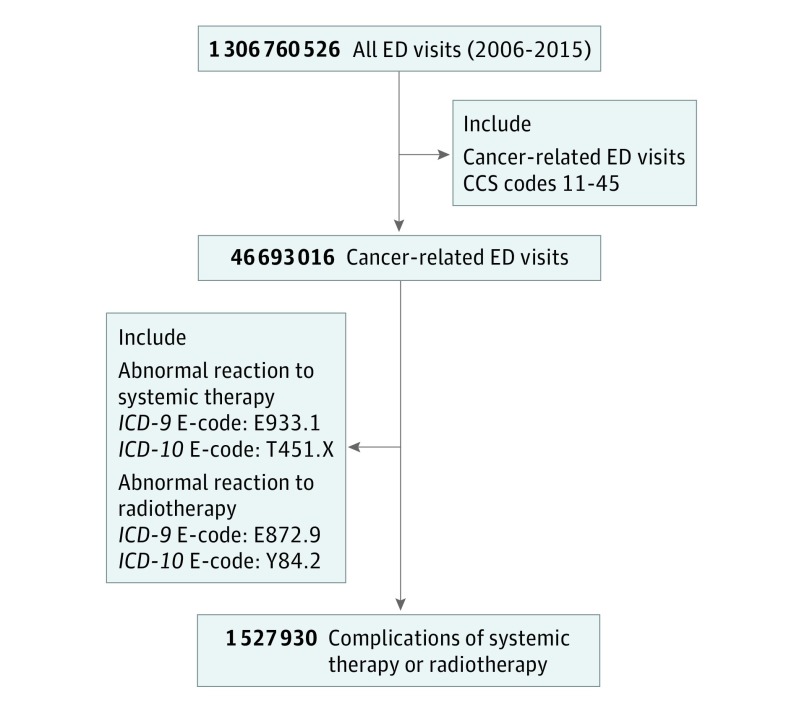

NEDS was queried from January 2006 to December 2015 for all patients with a cancer diagnosis who had complications of systemic therapy or radiotherapy. Data analysis was conducted from February 22 to December 23, 2018. First, patients with cancer were identified using ED visits in which a cancer diagnosis was coded according to the Clinical Classifications Software codes 11-45 as described previously.8 Then, using external cause of injury codes (E-codes), all patients with complications of systemic therapy (ICD-9-CM: E933.1 and ICD-10-CM: T451.X) or radiotherapy (ICD-9-CM: E879.2 and ICD-10-CM: Y84.2) were extracted from the database. The primary reason for the visit was identified as the first listed noncancer diagnosis. A full list of ICD-9-CM, ICD-10-CM, and the Clinical Classifications Software codes used to define complications is detailed in eTable 1 in the Supplement. A CONSORT diagram outlining the methods used to identify the patient cohort is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram of Inclusion Criteria for Study.

CCS indicates Clinical Classifications Software; E-code, external cause of injury code; ED, emergency department; ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; and ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification.

Emergency department visits and inpatient stays were characterized by demographic factors (age, sex, year, and location), socioeconomic factors (insurance type, median household income by zip code), hospital characteristics (teaching status, trauma designation), and complications. Treatment-related complications were further characterized by cancer type. Cancers were classified as either hematologic malignancies or solid tumors as reported in Table 1. Primary outcome variables included inpatient admission and total charges, adjusted for inflation to 2015 dollars using the Medical Care Consumer Price Index.15 Inpatient mortality was examined as a secondary outcome.

Table 1. Tumor Types of Patients Presenting to Emergency Departments for Complications of Systemic Therapy or Radiotherapy, 2006-2015.

| Tumor Type | No. of Visits (N = 1 527 930) (%)a |

|---|---|

| Solid | |

| Bladder | 38 144 (2.5) |

| Bone and connective tissue | 21 455 (1.4) |

| Brain and nervous system | 22 972 (1.5) |

| Breast | 201 331 (13.2) |

| Cervix | 33 301 (2.2) |

| Colon | 103 989 (6.8) |

| Esophagus | 31 824 (2.1) |

| Head and neck | 71 140 (4.7) |

| Kidney and renal | 2696 (0.2) |

| Liver and intrahepatic bile duct | 16 592 (1.1) |

| Lung | 305 982 (20.0) |

| Melanoma | 16 501 (1.1) |

| Other | 56 793 (3.7) |

| Ovary | 55 723 (3.6) |

| Pancreas | 47 588 (3.1) |

| Prostate | 113 579 (7.4) |

| Rectum and anus | 55 622 (3.6) |

| Stomach | 24 646 (1.6) |

| Testis | 7995 (0.5) |

| Thyroid | 7539 (0.5) |

| Uterus | 35 467 (2.3) |

| Liquid | |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 19 760 (1.3) |

| Leukemia | 117 301 (7.7) |

| Multiple myeloma | 52 304 (3.4) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 148 902 (9.7) |

The total number of patients with individual cancers sums to more than the total number of patients in the study cohort because some patients had more than 1 type of cancer.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to characterize temporal, demographic, and socioeconomic factors as well as hospital characteristics. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify factors associated with inpatient admission. Variables associated with inpatient admission on univariate analysis were included in the final multivariate model. In a secondary analysis, multivariate logistic regression was used to examine complications associated with inpatient mortality. Complications in all regression analyses were limited to the top 10 most common diagnoses. Median and total charges for each complication were estimated and compared. Weighted frequencies were incorporated in all analyses to produce national estimates. Hypothesis testing was 2-sided, and P < .005 was used to indicate statistical significance for all comparisons. Because of the large sample size in this data set, this P value was chosen to increase the likelihood of obtaining clinically relevant findings.16 Data analysis was carried out using Stata, version 13.1 (StataCorp LP).

Results

Characteristics of the Cohort

A weighted total of 1.3 billion ED visits occurred between 2006 and 2015, of which 1 527 930 were identified as associated with a complication due to systemic therapy or radiotherapy. Baseline characteristics of this cohort are described in eTable 2 in the Supplement. The mean age was 63.3 years and 53.2% were female. Most patients used Medicare (55.1%) and received care at a nontrauma center (64.8%). Among treatment-related ED visits, 90.9% resulted in hospital admission and 4.9% in death during hospitalization. Since 2006, the annual rate of increase in cancer treatment-related ED visits was 10.8% compared with all ED visits, which was 2.0%. Emergency department visits owing to sepsis (5.2-fold) and anemia (3.1-fold) had the highest relative increase from 2006 to 2015; associations with dehydration had the lowest (0.7-fold) (eFigure in the Supplement).

The top 10 individual complications were then examined by admission rate, mortality rate, and total charges (Table 2). A more comprehensive list of treatment-related complications is given in eTable 3 in the Supplement. The 3 most common complications were neutropenia (136 167 [8.9%]), sepsis (128 171 [8.4%]), and anemia (117 557 [7.7%]). Among the top 10 most frequent complications, sepsis had the highest admission (99.4%) and mortality (17.0%) rates; nausea and vomiting had the lowest admission (66.9%) and mortality (0.6%) rates. Among patients who were not admitted, nausea (13.8%), anemia (7.0%), and neutropenia (5.3%) were the most common diagnoses. Sepsis ($11.21 billion), anemia ($6.78 billion), and neutropenia ($5.52 billion) had the highest costs related to ED visits; the top 10 complications comprised 48% ($38 billion) of total charges for all complications. Sepsis ($49 587), pneumonia ($34 014), and acute kidney injury (AKI) ($32 819) had the highest median charge per visit.

Table 2. Top 10 Complications of Systemic Therapy or Radiotherapy With Associated Admission, Mortality Rates, and Charges, 2006-2015.

| Diagnosis | Visits, No. (%) | Rate, % | Total Charges (Billions), $ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admission | Mortality | |||

| Neutropenia | 136 167 (8.9) | 94.6 | 1.9 | 5.52 |

| Sepsis | 128 171 (8.4) | 99.4 | 17.0 | 11.21 |

| Anemia | 117 557 (7.7) | 91.7 | 3.6 | 6.78 |

| Pneumonia | 80 451 (5.3) | 98.8 | 7.7 | 5.11 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 58 077 (3.8) | 66.9 | 0.6 | 1.02 |

| Dehydration | 52 012 (3.4) | 86.9 | 2.5 | 1.44 |

| Acute kidney injury | 47 830 (3.1) | 99.0 | 8.1 | 3.10 |

| Intestinal obstruction (without hernia) | 34 078 (2.2) | 97.9 | 2.9 | 1.88 |

| Gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage | 24 265 (1.6) | 93.4 | 3.9 | 1.01 |

| Congestive heart failure | 23 718 (1.6) | 97.8 | 4.2 | 1.15 |

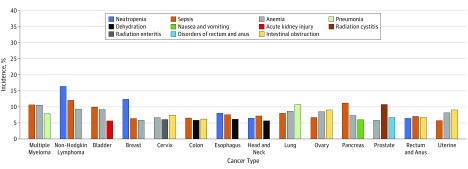

Treatment-related complications were then analyzed by cancer type. The most common complications for the top 15 cancers in the study cohort are shown in Figure 2. The most frequently represented cancer types were lung cancer (20.0%), breast cancer (13.2%), and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (9.7%). Among hematologic malignancies, the most common complications were neutropenia (15.0%), sepsis (11.6%), and anemia (11.5%); among solid tumors, the most common were sepsis (7.4%), neutropenia (7.3%), and anemia (6.7%). Dehydration was among the top 3 complications for head and neck, colon, and esophageal cancers. Intestinal obstruction was in the top 3 complications for gynecologic (cervix, uterus, and ovary) and gastrointestinal (GI) (colon, as well as rectum and anus) cancers. Prostate cancer was the most common malignancy (20.6%) among patients with GI hemorrhage; breast cancer (22.0%) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (17.3%) were the most common malignant neoplasms among patients with congestive heart failure.

Figure 2. Treatment-Related Complications by Cancer Subtype.

The 3 most frequent complications for the top 15 most common cancers are depicted in this graph.

Factors Associated With Inpatient Admission and Mortality

Demographic factors associated with inpatient admission (Table 3) include older age and male sex (odds ratio [OR], 1.15; 95% CI, 1.11-1.19). Complications associated with the highest odds for inpatient admission were sepsis (OR, 21.00; 95% CI, 14.61-30.20), pneumonia (OR, 9.73; 95% CI, 8.08-11.73), and AKI (OR, 9.60; 95% CI, 7.77-11.85). Complications associated with inpatient mortality were sepsis (OR, 5.15; 95% CI, 4.89-5.43), AKI (OR, 2.18; 95% CI, 2.00-2.38), and pneumonia (OR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.93-2.25) (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Table 3. Multivariate Analysis for Factors Associated With Inpatient Admission for Cancer Treatment-Related Complications, 2006-2015.

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Year | ||

| 2006-2009 | 1 [Reference] | |

| 2010-2012 | 1.17 (1.03-1.32) | .01 |

| 2013-2015 | 0.88 (0.77-1.00) | .06 |

| Age | ||

| 0-17 | 1 [Reference] | |

| 18-39 | 1.32 (1.08-1.61) | .007 |

| 40-64 | 1.68 (1.38-2.04) | <.001 |

| ≥65 | 1.93 (1.58-2.34) | <.001 |

| Sex | ||

| Male (vs female) | 1.15 (1.11-1.19) | <.001 |

| Median household income, $a | ||

| 1-41 999 | 1 [Reference] | |

| 42 000-51 999 | 0.86 (0.80-0.92) | <.001 |

| 52 000-67 999 | 0.90 (0.84-0.97) | .004 |

| ≥68 000 | 0.91 (0.83-1.00) | .04 |

| Primary payer | ||

| Medicare | 1 [Reference] | |

| Medicaid | 0.94 (0.88-1.01) | .08 |

| Private | 0.83 (0.79-0.87) | <.001 |

| Self-pay | 0.73 (0.64-0.85) | <.001 |

| No charge | 0.98 (0.65-1.47) | .93 |

| Other | 0.91 (0.81-1.04) | .16 |

| Hospital trauma designation | ||

| Trauma center (vs nontrauma center) | 1.32 (1.17-1.48) | <.001 |

| Hospital teaching status | ||

| Nonmetropolitan hospital | 1 [Reference] | |

| Metropolitan teaching | 3.75 (3.26-4.30) | <.001 |

| Metropolitan nonteaching | 3.02 (2.65-3.44) | <.001 |

| Complicationb | ||

| Neutropenia | 2.46 (2.12-2.86) | <.001 |

| Sepsis | 21.00 (14.61-30.20) | <.001 |

| Anemia | 1.50 (1.39-1.62) | <.001 |

| Pneumonia | 9.73 (8.08-11.73) | <.001 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 0.29 (0.27-0.31) | <.001 |

| Dehydration | 0.70 (0.65-0.76) | <.001 |

| AKI | 9.60 (7.77-11.85) | <.001 |

| Intestinal obstruction (without hernia) | 6.10 (5.00-7.43) | <.001 |

| Gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage | 1.63 (1.43-1.88) | <.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 5.28 (4.21-6.63) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; OR, odds ratio.

Median household income of patient’s zip code.

Reference category is not having the diagnosis.

Discussion

This study provides a national analysis of cancer treatment–related complications in the ED and inpatient settings. The increase in cancer treatment–related ED visits outpaced that of overall ED visits during this time frame. On average, treatment-related visits increased by 11.0% per year, while overall ED visits increased by 2.0% per year. In general, patients presenting to the ED for management of treatment-related complications were older than 60 years, female, presenting at nontrauma centers, and had Medicare as their primary insurance. Neutropenia, sepsis, and anemia were the most common complications; lung cancer, breast cancer, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma were the most represented cancers. Older age, male sex, sepsis, pneumonia, and AKI were factors associated with inpatient admission; sepsis, AKI, and pneumonia were complications associated with inpatient mortality. The top 10 complications made up nearly 50% of the total costs of treatment-related complications.

The temporal and demographic trends described provide insights on a national level. The rate of increase in treatment-related ED visits outpaced that of total ED visits by 5.5-fold. One explanation could be that more older adults are receiving systemic therapy or radiotherapy who previously would not have been considered candidates for these therapies.17 Another possibility is that novel systemic therapies, such as targeted agents and immune checkpoint inhibitors, now offer hope to patients for whom more traditional chemotherapies have failed; however, these therapies come with their own toxic effects. The female predominance in our cohort may be explained by sex differences in perception of symptoms or decreased access to ambulatory care compared with men.18 This finding may also reflect that more women are actively undergoing cancer treatment. Patients tended to present to and were more likely to be admitted at metropolitan teaching hospitals compared with nonteaching hospitals. This finding is consistent with published data showing that academic hospitals are more likely to admit oncologic patients requiring intensive treatments or workups, while community hospitals most often admitted patients for palliative symptoms.19 The decreased admission rate in community hospitals may be explained by the variable acuity of palliative symptoms, which can often be managed in the ED as well as the transfer of high-acuity patients to larger academic hospitals. In addition, the hospitalization rate for the cohort was 90.9%, which is significantly higher than the 60% rate previously described for all patients with cancer.8 This difference is likely owing to the fact that patients with complications of treatment presenting to EDs are either critically ill or require supportive care, such as intravenous antibiotics or blood transfusions, which are best provided in an inpatient setting.

Previous studies have attempted to estimate the incidence of treatment-related complications but have been limited to singular diseases in specific populations.10,11,20,21,22,23,24 In the present study, neutropenia, sepsis, and anemia were the most prevalent complications in the entire cohort as well as among patients with hematologic malignancies. This finding is likely owing to systemic treatments, including chemotherapy as well as bone marrow transplantation, which are immunosuppressive. Patients who receive transplants are susceptible to complications, such as infections or graft-vs-host disease, with readmissions up to 40% within 30 days after discharge.25 Dehydration was seen commonly among patients with solid tumors, particularly in GI malignancies and head and neck cancers, where mucositis rates occur in up to 80% of patients and can lead to decreased oral intake.26 Bowel obstruction was also seen among patients with gynecologic and GI malignancies. Although often a complication of the cancer itself, bowel obstruction can also present as a long-term sequela of radiotherapy.27 Gastrointestinal tract bleeding was prevalent among patients with prostate cancer, likely secondary to acute or chronic rectal bleeding, which can be seen after radiotherapy.28 Congestive heart failure, often an age-related comorbidity, was especially common among patients with breast cancer and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, which may be explained by adverse effects from anthracycline chemotherapy or targeted therapies, such as trastuzumab.29,30

Complications associated with inpatient admission and mortality included sepsis, pneumonia, and AKI. Given that patients with cancer undergoing active treatment tend to be immunocompromised, sepsis is common among this group, with high morbidity and mortality rates. One report estimated the in-hospital mortality rate associated with severe sepsis among patients with cancer to be nearly 40%.31 Pneumonia is also among the leading causes of admission and mortality and can be fairly aggressive in patients with cancer.32,33 Patients with lung cancer are often susceptible to developing postobstructive pneumonia,34 but other types of complications, including health care–acquired pneumonia or community-acquired pneumonia, are seen frequently. Acute kidney injury is also a significant comorbidity in patients with cancer.35 Although the reasons for development of this complication are multifold, use of nephrotoxic systemic therapy agents, sepsis, and dehydration are common. Nausea, anemia, and neutropenia were the most common diagnoses in patients who were not admitted, suggesting that these complications could be successfully managed with supportive measures in the ED or with increased monitoring in an outpatient setting.

Treatment-related complications of cancer therapy were also associated with a significant financial burden. Other studies have examined the economic burden of treatment complications, including sepsis36 and neutropenia,37,38,39 using insurance claims data for analysis. One study examining the financial cost of chemotherapy-related complications in patients with metastatic breast cancer found that hematologic complications bore the highest inpatient cost, followed by infections.40 While NEDS uses the total hospital charges, which is often greater than the final cost incurred by the patient, relative comparisons can still be made. In this study, infectious complications, such as sepsis and pneumonia, were associated with the first- and fourth-highest costs, respectively. This finding may in part be due to the large proportion of patients with hematologic malignancies presenting with sepsis (11.6%), which also bears the highest median charge per visit.

The high hospitalization rate found in our study represents a potential avenue for identification and coordination of patients whose treatment could be managed in the outpatient setting to significantly decrease costs. Recognizing the magnitude of this problem, the National Cancer Institute and Office of Emergency Care Research created a program to identify research opportunities in and advance the understanding of patients with cancer in emergency settings.41 Although multiple studies have highlighted strategies to reduce unplanned ED visits and hospitalizations among patients with cancer,42,43 we believe that these methods can be grouped into 2 categories: (1) enhanced outpatient management and (2) improved ED triage (eTable 5 in the Supplement). In the outpatient setting, validated risk assessment models have been safely used to identify low-risk patients with febrile neutropenia that could be managed with oral antibiotics.44,45 Other techniques, such as symptom management clinics46 and oncologic urgent care centers,43 have been shown to reduce ED visits, while telephone triage services have decreased ED visits by up to 60%.47 In the ED, triage systems can be used to decrease inpatient admission. Options to achieve this end point include dedicated oncologic EDs48 and oncologist-staffed EDs.49 Observation units have also reduced inpatient admissions through the ED, particularly for low-acuity conditions, such as fluid and electrolyte disorders and nausea.50 Although many of these models will require initial up-front investment, it stands to reason that reduced ED visits and hospitalizations should lead to increased cost savings in the future.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study lies in the characterization of treatment-related complications. Determination of whether an ED visit is associated with a complication of treatment is nuanced and requires input from multiple health care professionals, which is logistically difficult in an ED setting. The approach used in this study to select patients with treatment-related complications relied on E-codes. However, E-codes are thought to be underused in health care billing data51 because they are not required for reimbursement, resulting in a likely underascertainment of the incidence of complications. Another approach would have been to query NEDS using an alternative but related outcome. For example, ED diagnoses for patients who concurrently were coded as undergoing cancer treatment could have been analyzed. This information would have been potentially more specific for presentations temporally but would have also included both complications and noncomplications of treatment (eTable 6 in the Supplement). Furthermore, this approach would have selected against complications and long-term sequelae that occur after completion of treatment.

The other limitations of this study are inherent to those of the NEDS database. First, NEDS does not code for race/ethnicity, which is an important demographic variable. Second, some EDs may not be staffed by board-certified, emergency medicine–trained physicians, which may affect how complications are diagnosed, billed, and treated. Third, NEDS is not a longitudinal database and does not have patient-level data, which precludes tracking individual outcomes over time. Similarly, dates of prior treatments or therapies are not included. Fourth, NEDS does not capture data on tumor staging, and treatment-level data are sparse. Fifth, the primary reason for the visit was defined as the first listed noncancer diagnosis, which presupposes that patients present for 1 problem rather than multiple complications. However, given the overall paucity of data on treatment-related toxic effects requiring hospitalization as well as the rarity of some of these conditions, NEDS is one of the few databases that can be used to study such topics.

Conclusions

Cancer treatment–related hospitalizations are a significant national issue. This study found that, from 2006 to 2015, presentations to EDs for complications of systemic therapy and radiotherapy increased at a 5.5-fold higher rate compared with the overall number of ED visits. Neutropenia, sepsis, and anemia appeared to be the most frequent and costliest complications; sepsis, pneumonia, and AKI were associated with inpatient admission and mortality. More attention should be focused on anticipating, monitoring, and proactively addressing treatment-related complications in the outpatient setting. Further study is needed to characterize treatment-related toxic effects as well as their resultant financial burden.

eTable 1. ICD and CCS Codes Used to Define Complication Groups

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics of Study Sample

eTable 3. Top 30 Diagnoses Amongst Patients Presenting to the ED for Complications of Systemic Therapy or Radiotherapy, 2006-2015

eTable 4. Multivariate Analysis for Complications Associated With Inpatient Mortality, 2006 to 2015

eTable 5. Strategies to Decrease ED Visits and Inpatient Admissions Amongst Patients with Cancer

eTable 6. Top 10 Most Common ED Diagnoses Amongst Patients Currently Undergoing Active Systemic Therapy or Radiotherapy, 2006-2015

eFigure. Relative Change in Number of ED Visits for the Top 10 Treatment-Related Complications From 2006-2015

References

- 1.Halpern MT, Yabroff KR. Prevalence of outpatient cancer treatment in the United States: estimates from the Medical Panel Expenditures Survey (MEPS). Cancer Invest. 2008;26(6):647-651. doi: 10.1080/07357900801905519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toale K, Johnson T, Ma M Chemotherapy-induced toxicities. In: Thomas CR Jr, ed. Oncologic Emergency Medicine: Principles and Practice Geneva, Switzerland: Springer; 2016:381-406. [Google Scholar]

- 3.FitzGerald T, Bishop-Jodoin M, Laurie F. Treatment toxicity: radiation In: Thomas CR Jr, ed. Oncologic Emergency Medicine: Principles and Practice. Geneva, Switzerland: Springer; 2016:407-420. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-26387-8_34 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aprile G, Pisa FE, Follador A, et al. . Unplanned presentations of cancer outpatients: a retrospective cohort study. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(2):397-404. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1524-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adelson KB, Dest V, Velji S, Lisitano R, Lilenbaum R. Emergency department (ED) utilization and hospital admission rates among oncology patients at a large academic center and the need for improved urgent care access [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(30)(suppl):19. doi: 10.1200/jco.2014.32.30_suppl.1924276775 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manzano J-GM, Luo R, Elting LS, George M, Suarez-Almazor ME. Patterns and predictors of unplanned hospitalization in a population-based cohort of elderly patients with GI cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(31):3527-3533. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.3131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mueller EL, Sabbatini A, Gebremariam A, Mody R, Sung L, Macy ML. Why pediatric patients with cancer visit the emergency department: United States, 2006-2010. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(3):490-495. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rivera DR, Gallicchio L, Brown J, Liu B, Kyriacou DN, Shelburne N. Trends in adult cancer–related emergency department utilization: an analysis of data from the nationwide emergency department sample. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(10):e172450. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.2450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayer DK, Travers D, Wyss A, Leak A, Waller A. Why do patients with cancer visit emergency departments? results of a 2008 population study in North Carolina. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(19):2683-2688. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.2816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pittman NM, Hopman WM, Mates M. Emergency room visits and hospital admission rates after curative chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(2):120-125. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.000257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Du XL, Osborne C, Goodwin JS. Population-based assessment of hospitalizations for toxicity from chemotherapy in older women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(24):4636-4642. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.05.088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waddle MR, Chen RC, Arastu NH, et al. . Unanticipated hospital admissions during or soon after radiation therapy: Incidence and predictive factors. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2015;5(3):e245-e253. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2014.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services MACRA. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs.html. Updated September 21, 2018. Accessed June 16, 2018.

- 14.Pyenson BS, Fitch KV Cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: opportunities for better management. Milliman Inc. http://us.milliman.com/uploadedFiles/insight/research/health-rr/cancer-patients-receiving-chemotherapy.pdf. Published March 30, 2010. December 29, 2018.

- 15.United States Department of Labor Databases, tables & calculators by subject. https://data.bls.gov/pdq/SurveyOutputServlet. Updated February 28, 2019. Accessed December 29, 2018.

- 16.Ioannidis JPA. The proposal to lower P value thresholds to .005. JAMA. 2018;319(14):1429-1430. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lang K, Marciniak MD, Faries D, et al. . Trends and predictors of first-line chemotherapy use among elderly patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer in the United States. Lung Cancer. 2009;63(2):264-270. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baibergenova A, Thabane L, Akhtar-Danesh N, Levine M, Gafni A, Leeb K. Sex differences in hospital admissions from emergency departments in asthmatic adults: a population-based study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;96(5):666-672. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61063-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iezzoni LI, Shwartz M, Burnside S. Diagnostic Mix, Illness Severity, and Costs at Teaching and Nonteaching Hospitals. Springfield, VA: US Department of Commerce, National Technical Service; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tai E, Guy GP, Dunbar A, Richardson LC. Cost of cancer-related neutropenia or fever hospitalizations, United States, 2012. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(6):e552-e561. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.019588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brooks GA, Kansagra AJ, Rao SR, Weitzman JI, Linden EA, Jacobson JO. A clinical prediction model to assess risk for chemotherapy-related hospitalization in patients initiating palliative chemotherapy. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(4):441-447. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hassett MJ, Rao SR, Brozovic S, et al. . Chemotherapy-related hospitalization among community cancer center patients. Oncologist. 2011;16(3):378-387. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hassett MJ, O’Malley AJ, Pakes JR, Newhouse JP, Earle CC. Frequency and cost of chemotherapy-related serious adverse effects in a population sample of women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(16):1108-1117. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Neill CB, Atoria CL, O’Reilly EM, et al. . ReCAP: hospitalizations in older adults with advanced cancer: the role of chemotherapy. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(2):151-152, e138-e148. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.004812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bejanyan N, Bolwell BJ, Lazaryan A, et al. . Risk factors for 30-day hospital readmission following myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT). Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(6):874-880. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.10.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trotti A, Bellm LA, Epstein JB, et al. . Mucositis incidence, severity and associated outcomes in patients with head and neck cancer receiving radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy: a systematic literature review. Radiother Oncol. 2003;66(3):253-262. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8140(02)00404-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stacey R, Green JT. Radiation-induced small bowel disease: latest developments and clinical guidance. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2014;5(1):15-29. doi: 10.1177/2040622313510730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takemoto S, Shibamoto Y, Ayakawa S, et al. . Treatment and prognosis of patients with late rectal bleeding after intensity-modulated radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2012;7(1):87. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-7-87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larsen C, Dasari H, Calle MCA, et al. . Short and long term risk of congestive heart failure in breast cancer and lymphoma patients compared to controls: an epidemiologic study [abstract]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(11)(suppl):A695. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(18)31236-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldhar HA, Yan AT, Ko DT, et al. . The temporal risk of heart failure associated with adjuvant trastuzumab in breast cancer patients: a population study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;108(1):djv301. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams MD, Braun LA, Cooper LM, et al. . Hospitalized cancer patients with severe sepsis: analysis of incidence, mortality, and associated costs of care. Crit Care. 2004;8(5):R291-R298. doi: 10.1186/cc2893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rabello LSCF, Silva JRL, Azevedo LCP, et al. . Clinical outcomes and microbiological characteristics of severe pneumonia in cancer patients: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0120544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong JL, Evans SE. Bacterial pneumonia in patients with cancer: novel risk factors and management. Clin Chest Med. 2017;38(2):263-277. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2016.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rolston KVI, Nesher L. Post-obstructive pneumonia in patients with cancer: a review. Infect Dis Ther. 2018;7(1):29-38. doi: 10.1007/s40121-018-0185-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gallieni M, Cosmai L, Porta C. Acute kidney injury in cancer patients. Contrib Nephrol. 2018;193:137-148. doi: 10.1159/000484970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arefian H, Heublein S, Scherag A, et al. . Hospital-related cost of sepsis: a systematic review. J Infect. 2017;74(2):107-117. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caggiano V, Weiss RV, Rickert TS, Linde-Zwirble WT. Incidence, cost, and mortality of neutropenia hospitalization associated with chemotherapy. Cancer. 2005;103(9):1916-1924. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weycker D, Malin J, Edelsberg J, Glass A, Gokhale M, Oster G. Cost of neutropenic complications of chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(3):454-460. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schilling MB, Parks C, Deeter RG. Costs and outcomes associated with hospitalized cancer patients with neutropenic complications: a retrospective study. Exp Ther Med. 2011;2(5):859-866. doi: 10.3892/etm.2011.312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rashid N, Koh HA, Baca HC, Lin KJ, Malecha SE, Masaquel A. Economic burden related to chemotherapy-related adverse events in patients with metastatic breast cancer in an integrated health care system. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 2016;8:173-181. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S105618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown J, Grudzen C, Kyriacou DN, et al. . The emergency care of patients with cancer: setting the research agenda. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(6):706-711. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Handley NR, Schuchter LM, Bekelman JE. Best practices for reducing unplanned acute care for patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14(5):306-313. doi: 10.1200/JOP.17.00081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adelson KB, Velji S, Patel K, Chaudhry B, Lyons C, Lilenbaum R. Preparing for value-based payment: a stepwise approach for cancer centers. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(10):e924-e932. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.014605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klastersky J, Paesmans M, Georgala A, et al. . Outpatient oral antibiotics for febrile neutropenic cancer patients using a score predictive for complications. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(25):4129-4134. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.9909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carmona-Bayonas A, Jiménez-Fonseca P, Virizuela Echaburu J, et al. . Prediction of serious complications in patients with seemingly stable febrile neutropenia: validation of the Clinical Index of Stable Febrile Neutropenia in a prospective cohort of patients from the FINITE study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(5):465-471. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.2347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mason H, DeRubeis MB, Foster JC, Taylor JM, Worden FP. Outcomes evaluation of a weekly nurse practitioner-managed symptom management clinic for patients with head and neck cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40(6):581-586. doi: 10.1188/13.ONF.40-06AP [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hunis B, Alencar AJ, Castrellon AB, Raez LE, Guerrier V. Making steps to decrease emergency room visits in patients with cancer: our experience after participating in the ASCO Quality Training Program [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(7)(suppl):51. doi: 10.1200/jco.2016.34.7_suppl.51 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Delatore LR, Adkins E, Ebeling B, Gill M, Beck B, Moseley MG. Opening an integrated cancer specific emergency department in a tertiary academic hospital: operational planning and preliminary analysis of operations, quality, and patient populations [abstract 109]. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(4)(suppl):S44. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.08.121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brooks GA, Chen EJ, Murakami MA, Giannakis M, Baugh CW, Schrag D. An ED pilot intervention to facilitate outpatient acute care for cancer patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(10):1934-1938. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.06.076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lipitz-Snyderman A, Klotz A, Atoria CL, Martin S, Groeger J. Impact of observation status on hospital use for patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(2):73-77. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davidov DM, Larrabee H, Davis SM. United States emergency department visits coded for intimate partner violence. J Emerg Med. 2015;48(1):94-100. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.07.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. ICD and CCS Codes Used to Define Complication Groups

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics of Study Sample

eTable 3. Top 30 Diagnoses Amongst Patients Presenting to the ED for Complications of Systemic Therapy or Radiotherapy, 2006-2015

eTable 4. Multivariate Analysis for Complications Associated With Inpatient Mortality, 2006 to 2015

eTable 5. Strategies to Decrease ED Visits and Inpatient Admissions Amongst Patients with Cancer

eTable 6. Top 10 Most Common ED Diagnoses Amongst Patients Currently Undergoing Active Systemic Therapy or Radiotherapy, 2006-2015

eFigure. Relative Change in Number of ED Visits for the Top 10 Treatment-Related Complications From 2006-2015