Key Points

Question

How do the short-term outcomes following combined surgery and extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage compare with those of open surgery alone for treatment of locally advanced gastric cancer?

Findings

In this multicenter randomized clinical trial that included 550 adults, the overall postoperative complication rate following surgery alone (17%) was significantly higher than that following combined surgery and lavage (11.1%). Patients receiving surgery plus lavage also exhibited reduced mortality and postoperative pain compared with those receiving surgery alone.

Meaning

Patients may benefit from the addition of extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage with surgery for treatment of locally advanced gastric cancer.

Abstract

Importance

Peritoneal metastasis is the most frequent pattern of postoperative recurrence in patients with gastric cancer. Extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage (EIPL) is a new prophylactic strategy for treatment of peritoneal metastasis of locally advanced gastric cancer; however, the safety and efficacy of EIPL is currently unknown.

Objective

To evaluate short-term outcomes of patients with advanced gastric cancer who received combined surgery and EIPL or surgery alone.

Design, Setting, and Participants

From March 2016 to November 2017, 662 patients with advanced gastric cancer receiving D2 gastrectomy were enrolled in a large, multicenter, randomized clinical trial from 11 centers across China. In total, 329 patients were randomly assigned to receive surgery alone, and 333 patients were randomly assigned to receive surgery plus EIPL. Clinical characteristics, operative findings, and postoperative short-term outcomes were compared between the 2 groups in the intent-to-treat population.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Short-term postoperative complications and mortality.

Results

The present analysis included data from 550 patients, 390 men and 160 women, with a mean (SD) age of 60.8 (10.7) years in the surgery alone group and 60.6 (10.8) in the surgery plus EIPL group. Patients assigned to the surgery plus EIPL group exhibited reduced mortality (0 of 279 patients) compared with those assigned to surgery alone (5 of 271 patients [1.9%]) (difference, 1.9%; 95% CI, 0.3%-3.4%; P = .02). A significant difference in the overall postoperative complication rate was observed between patients receiving surgery alone (46 patients [17.0%]) and those receiving surgery plus EIPL (31 patients [11.1%]) (difference, 5.9%; 95% CI, 0.1%-11.6%; P = .04). Postoperative pain occurred more often following surgery alone (48 patients [17.7%]) than following surgery plus EIPL (30 patients [10.8%]) (difference, 7.0%; 95% CI, 0.8%-13.1%; P = .02).

Conclusions and Relevance

Inclusion of EIPL can increase the safety of D2 gastrectomy and decrease postoperative short-term complications and wound pain. As a new, safe, and simple procedure, EIPL therapy is easily performed anywhere and does not require any special devices or techniques. Our study suggests that patients with advanced gastric cancer appear to be candidates for the EIPL approach.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02745509

This randomized clinical trial compares short-term outcomes following treatment with surgery or with surgery plus extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage among patients with advanced gastric cancer in China.

Introduction

Gastric cancer, the fourth most commonly diagnosed malignant neoplasm and the second leading cause of cancer death, constitutes a major international health problem.1,2 The standard treatment of gastric cancer after resection is chemotherapy. Peritoneal metastasis is the most frequent pattern of postoperative recurrence in patients with gastric cancer.3 The prognosis of patients with peritoneal metastasis remains extremely poor. The median survival time of such patients is 3 to 6 months.4

Peritoneal metastasis is caused by direct cancer cell dissemination from serosa-invasive tumors.2 Consequently, it is important to prevent peritoneal metastasis before the fixation of free cancer cells on the peritoneum.3 Two therapies are available to prevent this condition: intraperitoneal chemotherapy (IPC) and extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage (EIPL).

Intraperitoneal chemotherapy was first described in 1980.4 It was used to treat peritoneal metastasis through locoregional chemotherapy and cytoreduction of numerous malignant neoplasms.5,6,7,8 However, the value of IPC is still debated.6,8 Some studies have shown that IPC does not benefit the progress of patients with advanced gastric cancer (AGC). Moreover, the procedure is costly and associated with an increased rate of postoperative complications.7,8

Recently, the use of EIPL, a new lavage method that is similar to the so-called limiting dilution approach, has been of considerable interest in AGC.9,10 In 2009, Kuramoto et al11 reported that EIPL plus IPC reduces the number of intraperitoneal free cancer cells to potentially zero in patients with AGC. Therefore, these researchers advocate EIPL therapy as an optimal treatment protocol for AGC.4 However, the safety and efficacy of EIPL for treatment of AGC has not been defined to date.

Currently, 3 multicenter randomized clinical trials (RCTs) are ongoing to assess the value of EIPL as standard prophylactic treatment of peritoneal recurrence of local AGC. These studies are being conducted in Japan ([CCOG1102 RCT]12; a randomized trial exploring the prognostic value of extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage for resectable AGC), Singapore ([EXPEL RCT]13; extensive peritoneal lavage after curative gastrectomy for gastric cancer), and China ([SEIPLUS RCT]; EIPL after curative gastrectomy for locally AGC).

In the present study, we aim to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of EIPL. The overall survival of these patients is still being assessed in the follow-up phase. We are scheduled to analyze the primary end point of 3-year overall survival in 2020.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This was a multicenter parallel-group randomized trial. All patients with local AGC from 11 participating hospitals in China were screened for inclusion in the trial from March 2016 to November 2017. Eligibility criteria are given in the Box. The preoperative staging modalities included multidetector computed tomographic scans and ultrasonographic gastroscopy. The ethics committees of every participating center provided ethical approval for the trial. All candidates provided written informed consent. The study protocol is available in Supplement 1.

Box. Eligibility Criteria for Enrolling Patients.

Preoperative Inclusion Criteria

Aged between 18 and 80 y

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status 0 or 1

Written informed consent

Open surgery

Preoperative evaluation of cT3/4NanyM0 according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual, seventh edition

Intraoperative Inclusion Criteria

Macroscopic appearance in exploratory laparotomy of cT3/4NanyM0

R0 surgery

Exclusion Criteria

Previous neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy

Peritoneal dissemination, distant lymph nodes, ovary, liver, lung, brain, or bone metastases

Massive ascites or cachexia

Current participation in any other clinical trial

Severe cardiovascular, respiratory tract, kidney, liver, or psychiatric disease or diabetes

Poor compliance

Randomization and Masking

Patients were randomized by the trial coordinator (D. Xu) at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou, China. Patients were randomized to the EIPL plus surgery or the surgery alone group in a 1:1 ratio (with a block size of 4). Randomization was stratified by participating center. Allocation was performed using sealed opaque envelopes that contained computer-generated random numbers and the procedure to which patients were allocated. The envelopes were opened after exploratory laparotomy. Patients were blinded to their procedure. Intent-to-treat analysis was used for all participants who met the inclusion criteria.

Patients were excluded after randomization only if stage T1, T2, or M1 disease was detected as a histopathologic result. Data from 550 patients with a pathologic depth of invasion confined to the subserosal or serosal layer (pT3/4NanyM0) were analyzed. The American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual, seventh edition, criteria for gastric cancer staging was used for TNM classification.14 The Borrmann classification was provided as a baseline characteristic of the intention-to-treat population.15

Procedures

All patients had open curative D2 gastrectomy and achieved margin-negative (R0) resection. Depending on the location of the primary tumor, surgeons (A.X., X.S., X.Z., Y.X., H.R., Y.Z., R.Z., L.C., T.Z., G.L., H.X., and D.X.) performed either total, proximal subtotal, or distal subtotal gastrectomy. The D2 gastrectomy was defined by the guidelines of the Japanese Research Society for the Study of Gastric Cancer.16 Before the start of the study, standard operating procedures were predefined and given to all surgeons to ensure the quality of the surgical procedure. All surgeons had sufficient experience for D2 gastrectomy (>100 procedures per year at each institute).

After the potentially curative operation, EIPL was performed. Patients assigned to the surgery alone group received conventional peritoneal lavage using less than 3 L of physiological saline (<3 times). Patients assigned to the EIPL group received EIPL using 10 L of physiological saline (1 L for 10 times). Every time, the peritoneal cavity was stirred and washed, and the fluid was completely aspirated.

All patients were recommended to undergo eight 3-week cycles of oral S-1 (40 mg/m2 twice daily on days 1-14 of each cycle) plus intravenous oxaliplatin (100 mg/m2 on day 1 of each cycle) postoperatively. Patients received chemotherapy for 2 weeks (days 1-14), followed by 1 week of no chemotherapy (days 15-21). Dose reductions or interruptions were used to manage potentially serious or life-threatening adverse events.

Outcomes

The end points reported herein are short-term postoperative complications and mortality. During the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative periods, all patients were observed and the observations recorded. Mortality (death within 30 days of the operation or during a hospital stay), complications (eg, ileus, abscess, hemorrhage, and leakage), laboratory and pathologic findings, abdominal pain, time to first flatus, and length of hospital stay were evaluated. Major bleeding was defined as an amount of hemorrhage exceeding 300 mL. Ileus, abscess, and leakage were diagnosed by clinical suspicion and postoperative radiologic examination. The Clavien-Dindo classification was used to assess the severity of postoperative complications.17 Pain intensity was assessed postoperatively using a numerical rating scale that ranged from 0 to 10 (0, no pain; 1-3, mild pain [nagging, annoying, interfering little with daily living activities]; 4-6, moderate pain [substantially interfering with daily living activities]; 7-10, severe pain [disabling; unable to perform daily living activities]). In this trial, pain was defined as greater than 3 on the scale, which was considered to potentially affect emotional or physical functioning.18

Statistical Analysis

This study was designed to assess the superiority in terms of overall survival of combining surgery and EIPL compared with surgery alone. We calculated using the log-rank test with a 2-sided α level of .05 and a power of 80% that 254 patients were needed in each group to detect a difference in 3-year overall survival of 60% for the surgery alone group and 71% for the EIPL plus surgery group.

The differences between groups were compared using χ2 tests and t tests. All P values calculated in the analysis were 2-sided, and P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 17.0 (IBM Corporation).

Results

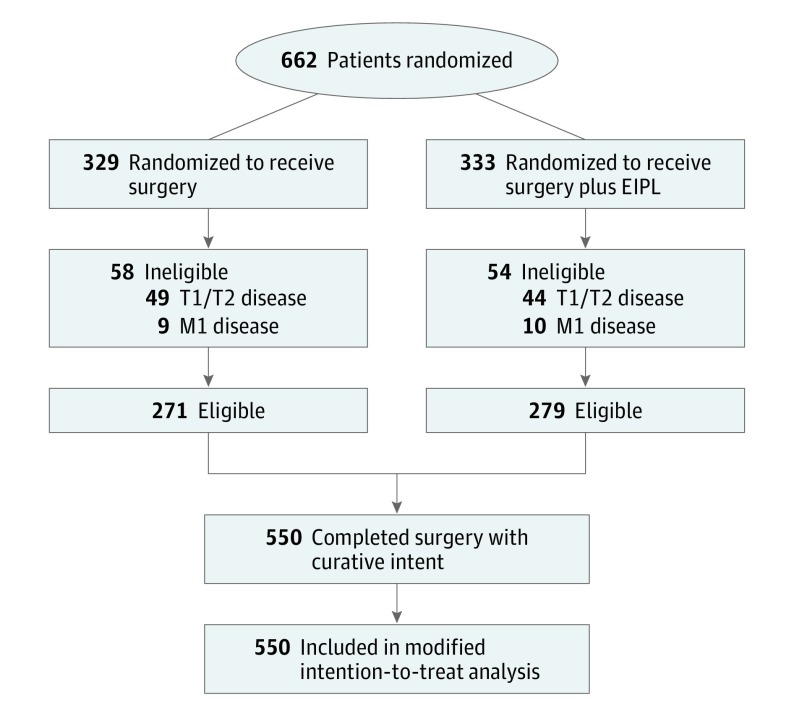

From March 2016 to November 2017, we enrolled and randomly assigned 662 patients from 11 centers in China, with 329 patients assigned to the surgery alone group and 333 assigned to the surgery plus EIPL group. The reasons for exclusion after randomization were stage IV cancer (including 11 patients with peritoneal metastasis, 6 patients with distance lymphatic metastasis, and 2 patients with liver metastasis) and T1/T2 cancers (93 patients) (Figure).

Figure. CONSORT Diagram of Patient Flow.

EIPL indicates extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage.

The present analysis included 550 patients (390 men and 160 women) who underwent surgery alone (n = 271) or surgery plus EIPL (n = 279), with a mean (SD) age of 60.8 (10.7) years in the surgery alone group and 60.6 (10.8) in the surgery plus EIPL group. Table 1 indicates that the baseline clinical characteristics of the 550 patients were well balanced between the intervention groups.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the Intention-to-Treat Population.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery Alone (n = 271) | Surgery Plus EIPL (n = 279) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 60.8 (10.7) | 60.6 (10.8) | .87 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 196 | 194 | .47 |

| Female | 75 | 85 | |

| Smoking status | |||

| Yes | 81 | 91 | .49 |

| No | 190 | 188 | |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 21.97 (3.01) | 22.16 (3.42) | .47 |

| Tumor location | |||

| Upper third | 85 | 81 | .78 |

| Middle third | 75 | 72 | |

| Lower third | 101 | 116 | |

| Total | 10 | 10 | |

| Tumor size, mean (SD), cm | 5.27 (3.02) | 5.25 (2.49) | .91 |

| Pathologic T category | |||

| T3 | 72 | 71 | .77 |

| T4 | 199 | 208 | |

| Pathologic N category | |||

| N0 | 50 | 47 | .73 |

| N1 | 49 | 61 | |

| N2 | 72 | 70 | |

| N3 | 100 | 101 | |

| Borrmann classificationa | |||

| I | 14 | 13 | .53 |

| II | 86 | 85 | |

| III | 141 | 159 | |

| IV | 30 | 22 | |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); EIPL, extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage.

The Borrmann classification scheme is explained in Kim et al.15

The surgical outcomes are presented in Table 2. Total and distal gastrectomy procedures were performed in a large proportion of patients (95.6%): 138 total, 122 distal, and 11 proximal gastrectomy procedures were performed in the surgery alone group, and 139 total, 127 distal, and 13 proximal gastrectomy procedures were performed in the surgery plus EIPL group. No significant differences were observed between the 2 groups with respect to time to first flatus and postoperative hospital stay.

Table 2. Surgical Outcomes Following Surgery Alone or Surgery With EIPL.

| Outcome | Mean (SD) Values | Between-Group Difference (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery Alone (n = 271) | Surgery Plus EIPL (n = 279) | |||

| Gastrectomy, No. (%) | ||||

| Total | 138 (50.9) | 139 (49.8) | ||

| Distal | 122 (45.0) | 127 (45.5) | ||

| Proximal | 11 (4.1) | 13 (4.7) | ||

| Additional organ resection, No. | 10 (3.7) | 15 (5.4) | ||

| Time to first flatus, d | 4.32 (1.41) | 4.19 (1.20) | 0.13 (−0.09 to 0.35) | .26 |

| Postoperative hospital stay, d | 18.47 (5.86) | 18.54 (5.89) | −0.07 (−1.06 to 0.92) | .89 |

| Postoperative laboratory results | ||||

| White blood cell count, /μL | 11 880 (3580) | 12 130 (4290) | −250 (−910 to 410) | .46 |

| Neutrophil count, /μL | 12 570 (14 630) | 11 600 (11 210) | 960 (−1230 to 3150) | .39 |

| Neutrophil lymphocyte ratio | 20.1 (31.2) | 21.3 (50.1) | −1.2 (−8.3 to 5.8) | .73 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 11.1 (1.9) | 11.1 (2.4) | 0.04 (−0.3 to 0.4) | .82 |

| Platelet, ×103/μL | 196 (84) | 197 (75) | −1.6 (−14.8 to 12.0) | .84 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.3 (8.7) | 3.2 (5.1) | 0.06 (−0.06 to 0.17) | .37 |

| Albumin globulin ratio | 1.4 (0.5) | 1.4 (0.3) | 0.04 (−0.03 to 0.11) | .25 |

Abbreviation: EIPL, extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage.

SI conversion factors: To convert white blood cell and neutrophil counts to ×109 per liter, multiply by 0.001; hemoglobin level to grams per liter, by 10; platelet count to ×109 per liter, by 1; and albumin level to grams per liter, by 10.

Whereas 5 deaths occurred in the surgery alone group (1 patient died of intra-abdominal bleeding, 3 patients died of respiratory failure, and 1 patient died of heart failure), zero deaths occurred during the study period in the surgery plus EIPL group across the various centers (difference, 1.9%; 95% CI, 0.3%-3.4%; P = .02) (Table 3).

Table 3. Postoperative Complications and Mortality.

| Complication | Patients, No. (%) | Between-Group Difference, % (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery Alone (n = 271) | Surgery and EIPL (n = 279) | |||

| Mortality | 5 (1.9) | 0 | 1.9 (0.3 to 3.4) | .02 |

| Abdominal pain | 48 (17.7) | 30 (10.8) | 7.0 (0.8 to 13.1) | .02 |

| Patients with at least 1 postoperative complication | 46 (17.0) | 31 (11.1) | 5.9 (0.1 to 11.6) | .04 |

| Ileus | 17 (6.3) | 14 (5.0) | ||

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 5 (1.9) | 2 (0.7) | ||

| Intra-abdominal bleeding | 7 (2.6) | 3 (1.1) | ||

| Wound problem | 7 (2.6) | 5 (1.8) | ||

| Anastomotic leakage | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) | ||

| Pancreatic leakage | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Anastomotic stenosis | 1 (0.4) | 0 | ||

| Cardiac disease | 2 (0.7) | 0 | ||

| Deep vein thrombosis | 2 (0.7) | 0 | ||

| Pulmonary disease | 9 (3.3) | 7 (2.5) | ||

| Clavien-Dindo classificationa | ||||

| I/II | 43 (15.9) | 30 (10.8) | 5.1 (−0.5 to 10.7) | .08 |

| III/IV | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.4) | 0.7 (−0.7 to 2.1) | .30 |

| V | 5 (1.9) | 0 | 1.9 (0.3 to 3.4) | .02 |

Abbreviation: EIPL, extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage.

The Clavien-Dindo classification scheme is explained in Dindo et al.17

Postoperative abdominal pain occurred more frequently in the surgery alone group (48 of 271 patients [17.7%]) compared with the surgery plus EIPL group (30 of 279 patients [10.8%]) (difference, 7.0%; 95% CI, 0.8%-13.1%; P = .02). Among 550 patients undergoing gastrectomy, 77 (14%) experienced at least 1 postoperative complication. A significant difference in the postoperative complication rate was observed between the surgery alone group (46 of 271 patients [17.0%]) and the surgery plus EIPL group (31 of 279 patients [11.1%]) (difference, 5.9%; 95% CI, 0.1%-11.6%; P = .04). Compared with the group of 271 patients receiving surgery alone, the group of 279 patients receiving surgery plus EIPL showed decreased morbidity due to ileus (17 patients [6.3%] vs 14 patients [5.0%]), intra-abdominal abscess (5 patients [1.9%] vs 2 patients [0.7%]), intra-abdominal bleeding (7 patients [2.6%]% vs 3 patients [1.1%]), wound problems (7 patients [2.6%] vs 5 patients [1.8%]), deep vein thrombosis 2 patients [0.7%] vs 0 patients), and cardiac (2 patients [0.7%] vs 0 patients) and pulmonary (9 patients [3.3%] vs 7 patients [2.5%]) disease postoperatively (Table 3).

Discussion

Previously, Kuramoto et al11 showed that EIPL plus IPC could improve the survival of patients with AGC. However, given that the role of IPC in AGC is debated, our intervention group involved only an EIPL component, without IPC. Another difference between their study and the present study is that they only recruited 88 patients with cytology-positive peritoneal lavage fluid.

The findings in the present study indicated that EIPL decreased the incidence of postoperative complications. For example, there were more cases of intra-abdominal abscess in the surgery alone group (5 patients [1.9%]) compared with the surgery plus EIPL group (2 patients [0.7%]). On the basis of previous clinical trial reports, the rate of intra-abdominal abscess is 1.3% to 17% after stomach surgery, which is higher than that observed for the surgery plus EIPL group in the present study.19,20,21

Indeed, EIPL appears to be a new and useful technique to minimize the risk of surgical infection. In contrast to the conventional lavage method, EIPL is performed 10 times using 1 L of physiological saline.22,23 The technique can largely reduce the amount of intraperitoneal damaged tissue and wound exudate and clean the peritoneal cavity, similar to the so-called limiting dilution method.23

We also found that EIPL significantly decreased postoperative pain. The reason for the decrease in pain might be related to a reduction in the inflammatory response. Pain perception is often triggered by local release of cytokines from inflammatory cells and is a clinical reflection of tissue damage and the inflammatory response.23,24 Schwarz et al25 and Kalff et al26 also found a postoperative inflammatory field-effect phenomenon within the manipulated gastrointestinal tract. Peritoneal lavage can remove bacterial materials, promoting proinflammatory cytokines.23,24 Notably, the use of EIPL with 1 L of saline for 10 rounds of washing and stirring of the abdominal cavity would be likely to remove metabolic waste and tissue debris that may enhance local inflammation.4

In addition, the rate of ileus in the EIPL group appeared lower than that in the surgery alone group. This finding is consistent with published results that indicate that a reduction in the postoperative inflammatory reaction could avoid adhesion formation that results in ileus.27,28

Whereas no deaths occurred in the surgery plus EIPL group, 5 deaths occurred in the surgery alone group during the study period. Three patients died of respiratory failure, and 1 patient died of heart failure. We considered these deaths to be associated with upregulation of the inflammatory reaction and postoperative pain.29 Tsui et al30 also found that controlled pain could decrease pulmonary and cardiovascular complications along with postoperative mortality.

In the present study, 1 patient died of intra-abdominal bleeding in the surgery alone group. We also observed more intra-abdominal bleeding cases (7 patients [2.58%]) in the surgery alone group compared with the EIPL group (3 patients [1.08%]). The use of EIPL may identify potential bleeding more easily via sufficient stirring and washing of the abdominal cavity.

Limitations

The present study has several limitations. First, the quality of the study may be decreased because 112 (16.9%) patients were excluded owing to T1, T2 or M1 disease. However, the balance was essentially unchanged in the 2 groups. Second, no objective inflammatory reaction measure was collected. Future studies could be designed to include in vitro and in vivo measures that would elucidate changes in inflammatory mechanisms associated with this new technique.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this study is the first to show that EIPL significantly reduced short-term postoperative complications, wound pain, and mortality associated with D2 gastrectomy. Including EIPL can increase safety and result in early recovery postoperatively. As a new, safe, and simple procedure, EIPL therapy is easily performed anywhere and does not require any special devices or techniques. Thus, EIPL is a promising and exciting therapeutic strategy for patients with AGC.

Trial Protocol

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Kunz PL, Gubens M, Fisher GA, Ford JM, Lichtensztajn DY, Clarke CA. Long-term survivors of gastric cancer: a California population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(28):3507-3515. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.8028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hagiwara A, Takahashi T, Kojima O, et al. Prophylaxis with carbon-adsorbed mitomycin against peritoneal recurrence of gastric cancer. Lancet. 1992;339(8794):629-631. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90792-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuramoto M, Shimada S, Ikeshima S, et al. A proposal of a practical and optimal prophylactic strategy for peritoneal recurrence. J Oncol. 2012;2012:340380. doi: 10.1155/2012/340380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spratt JS, Adcock RA, Muskovin M, Sherrill W, McKeown J. Clinical delivery system for intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 1980;40(2):256-260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang XJ, Huang CQ, Suo T, et al. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy improves survival of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastric cancer: final results of a phase III randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(6):1575-1581. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1631-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coccolini F, Cotte E, Glehen O, et al. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer: meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40(1):12-26. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2013.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glehen O, Mohamed F, Gilly FN. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from digestive tract cancer: new management by cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5(4):219-228. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01425-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glehen O, Kwiatkowski F, Sugarbaker PH, et al. Cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the management of peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal cancer: a multi-institutional study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(16):3284-3292. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mayer AD, McMahon MJ, Corfield AP, et al. Controlled clinical trial of peritoneal lavage for the treatment of severe acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(7):399-404. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198502143120703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hotchkiss LW. V. The treatment of diffuse suppurative peritonitis, following appendicitis. Ann Surg. 1906;44(2):197-208. doi: 10.1097/00000658-190608000-00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuramoto M, Shimada S, Ikeshima S, et al. Extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage as a standard prophylactic strategy for peritoneal recurrence in patients with gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2009;250(2):242-246. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b0c80e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Misawa K, Mochizuki Y, Ohashi N, et al. A randomized phase III trial exploring the prognostic value of extensive intraoperative peritoneal lavage in addition to standard treatment for resectable advanced gastric cancer: CCOG 1102 study. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2014;44(1):101-103. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyt157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim G, Chen E, Tay AY, et al. Extensive peritoneal lavage after curative gastrectomy for gastric cancer (EXPEL): study protocol of an international multicentre randomised controlled trial. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2017;47(2):179-184. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyw153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(6):1471-1474. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0985-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim J, Lee HH, Seo HS, Jung YJ, Park CH. Borrmann type 1 cancer is associated with a high recurrence rate in locally advanced gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(7):2044-2052. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6509-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14(2):113-123. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0042-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):205-213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laufenberg-Feldmann R, Kappis B, Mauff S, Schmidtmann I, Ferner M. Prevalence of pain 6 months after surgery: a prospective observational study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2016;16(1):91. doi: 10.1186/s12871-016-0261-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sano T, Sasako M, Yamamoto S, et al. Gastric cancer surgery: morbidity and mortality results from a prospective randomized controlled trial comparing D2 and extended para-aortic lymphadenectomy—Japan Clinical Oncology Group study 9501. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(14):2767-2773. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu Y, Huang C, Sun Y, et al. Morbidity and mortality of laparoscopic versus open D2 distal gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(12):1350-1357. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.7215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonenkamp JJ, Songun I, Hermans J, et al. Randomised comparison of morbidity after D1 and D2 dissection for gastric cancer in 996 Dutch patients. Lancet. 1995;345(8952):745-748. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)90637-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singal R, Dhar S, Zaman M, Singh B, Singh V, Sethi S. Comparative evaluation of intra-operative peritoneal lavage with super oxidized solution and normal saline in peritonitis cases; randomized controlled trial. Maedica (Buchar). 2016;11(4):277-285. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruiz-Tovar J, Llavero C, Muñoz JL, Zubiaga L, Diez M. Effect of peritoneal lavage with clindamycin-gentamicin solution on post-operative pain and analytic acute-phase reactants after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2016;17(3):357-362. doi: 10.1089/sur.2015.196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Cicco C, Schonman R, Ussia A, Koninckx PR. Extensive peritoneal lavage decreases postoperative C-reactive protein concentrations: a RCT. Gynecol Surg. 2015;12(4):271-274. doi: 10.1007/s10397-015-0897-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwarz NT, Kalff JC, Türler A, et al. Selective jejunal manipulation causes postoperative pan-enteric inflammation and dysmotility. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(1):159-169. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalff JC, Carlos TM, Schraut WH, Billiar TR, Simmons RL, Bauer AJ. Surgically induced leukocytic infiltrates within the rat intestinal muscularis mediate postoperative ileus. Gastroenterology. 1999;117(2):378-387. doi: 10.1053/gast.1999.0029900378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corona R, Verguts J, Schonman R, Binda MM, Mailova K, Koninckx PR. Postoperative inflammation in the abdominal cavity increases adhesion formation in a laparoscopic mouse model. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(4):1224-1228. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sortini D, Feo CV, Maravegias K, et al. Role of peritoneal lavage in adhesion formation and survival rate in rats: an experimental study. J Invest Surg. 2006;19(5):291-297. doi: 10.1080/08941930600889409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalff JC, Schraut WH, Billiar TR, Simmons RL, Bauer AJ. Role of inducible nitric oxide synthase in postoperative intestinal smooth muscle dysfunction in rodents. Gastroenterology. 2000;118(2):316-327. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(00)70214-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsui SL, Law S, Fok M, et al. Postoperative analgesia reduces mortality and morbidity after esophagectomy. Am J Surg. 1997;173(6):472-478. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(97)00014-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Data Sharing Statement