Abstract

This time series study evaluates whether increasing the threshold for identifying uropathogens is associated with a decrease in antimicrobial treatment.

Treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria and candiduria (ASB/C) remains a leading reason for unnecessary antimicrobial use among hospitalized patients, yet the optimal colony-count threshold for identifying and reporting growth from inpatient urine cultures (UCs) is unknown.1,2,3 Two prior studies suggest that UC growth from hospitalized patients with low colony counts of organisms (104 to 105 CFU [colony-forming units]/mL) was infrequently associated with urinary tract infection (UTI) but generated substantial antimicrobial prescribing for ASB/C.2,3

Methods

At our acute care hospital, the threshold for identifying potential uropathogens from UCs submitted from inpatient units was increased from 104 CFU/mL or greater to 105 CFU/mL or greater on March 1, 2017. Urine cultures with low colony counts, defined as 104 to 105 CFU/mL, were automatically issued a report stating that these organisms usually represent ASB/C, and could be identified at the telephone request of any clinician with a high suspicion for UTI. Urine specimens from outpatient units, emergency departments, maternity wards, cystoscopy locations, and suprapubic aspirations were excluded.

A controlled interrupted time series study was performed that included all patients with low-colony-count UC (the intervention group) and every second patient with a high-colony-count UC (defined as ≥105 CFU/mL; control group). The preintervention period was March 1, 2016, to February, 28 2017, and the postintervention period was March 1, 2017, to February 28, 2018. The rate of monthly treatment of ASB/C in study groups was adjudicated through retrospective chart review (κ = 0.84 with prospective audits) and compared using segmented regression (Poisson regression generalized linear model). Secondary outcomes included days of antimicrobial therapy for ASB/C, the proportion of patients with untreated UTIs based on surveillance definitions,4 bacteremia from a presumed urinary source, elevated serum lactate level within 7 days, and a composite clinical outcome of hospital readmission, death, or transfer to critical care within 14 days. Differences in proportion were compared using the χ2 test. The study was approved by the research ethics board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, and patient consent was waived.

Results

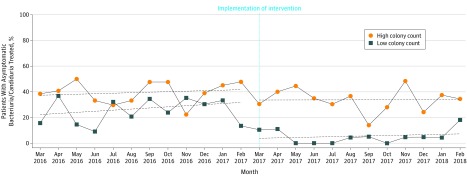

Over 2 years, there were 609 (30%) patients with a low colony count, and 1432 (70%) patients with a high colony count, of which 608 (nearly 100%) and 690 (48%) were included in the study, respectively. As depicted in the Figure, the intervention was associated with reduction in antimicrobial prescribing for ASB/C among the low-colony-count group compared with the high-colony-count group (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 0.14; 95% CI, 0.03-0.64; P = .01). When clinicians requested low-colony-count UCs to be worked up (n = 17), patients were more likely to have a UTI (6/17, 35% vs 17/237, 7%; P < .001). There were no significant changes in clinical outcomes between groups (Table).

Figure. Mean Monthly Proportion of Hospitalized Patients With ASB/C Treated With Antimicrobial Therapy.

ASB/C indicates asymptomatic bacteriuria and candiduria. The Poisson regression model demonstrates a significant reduction in antimicrobial treatment among patients with low-colony-count (intervention group; 104 to 105 colony-forming units [CFU]/mL) compared with high-colony-count (control group; 105 CFU/mL or greater) urine cultures.

Table. Characteristics and Outcomes of Hospitalized Patients With Urine Culture Growtha.

| Characteristic | Baseline | Intervention | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Colony Count (n = 349)b | High Colony Count (n = 333)c | Low Colony Count (n = 259)b | High Colony Count (n = 357)c | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, median (range), y | 69 (19-96) | 74 (18-100) | 71 (18-101) | 74 (19-102) |

| Female sex | 187 (54) | 204 (61) | 146 (56) | 198 (55) |

| Intensive care unit | 89 (26) | 68 (20) | 102 (39)d | 65 (18) |

| Catheterized | 107 (31) | 122 (37) | 112 (43)d | 124 (35) |

| Microbiology | ||||

| Escherichia coli | 75 (21) | 131 (39) | 4 (2) | 143 (40) |

| Other enterobacteriaceae | 42 (12) | 81 (24) | 4 (2) | 61 (17) |

| Enterococcus species | 91 (26) | 42 (13) | 9 (3) | 46 (13) |

| Yeast | 68 (19) | 20 (6) | 10 (4) | 31 (9) |

| Other organisms or mixed | 72 (21) | 59 (18) | 16 (6) | 76 (21) |

| Unavailablee | 1 (0) | 0 | 216 (83) | 0 |

| Clinical status | ||||

| ASB | 314 (90)d | 272 (82) | 236 (91)d | 296 (83) |

| UTI | 35 (10) | 61 (18) | 23 (9) | 61 (17) |

| Bacteremic UTI | 6 (2) | 10 (3) | 3 (1) | 6 (2) |

| Primary outcome | ||||

| Treatment of ASBf | 83 (38) | 121 (50) | 13 (10) | 100 (42) |

| Average DOT per patient for ASB, d | ||||

| Overall | 2.21 | 2.82 | 0.50d | 2.22 |

| β-Lactams | 0.83 | 0.95 | 0.20 | 0.91 |

| Quinolones | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.16 | 0.59 |

| Nitrofurantoin | 0.38 | 0.58 | 0.07 | 0.47 |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 0.05 | 0.34 | 0 | 0.14 |

| Others | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.10 |

| Clinical outcomes | ||||

| Composite clinical outcomeg | 71 (20) | 54 (16) | 51 (20) | 55 (15) |

| Untreated UTI | 1 (0) | 8 (2) | 3 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Bacteremia from urinary source | 6 (2) | 10 (3) | 3 (1) | 6 (2) |

| Elevated lactate | 36 (10) | 23 (7) | 29 (11) | 40 (11) |

Abbreviations: ASB, asymptomatic bacteriuria; DOT, days of therapy; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Unless otherwise noted, data are expressed as number (percent) of patients.

Low colony count was defined as 104 to 105 CFU/mL.

High colony count was defined as 105 CFU/mL or greater.

Indicates a significant value compared with high-colony-count group (P < .05).

During intervention period, low-colony-count urine cultures were not processed unless a telephone request was received.

In patients with no alternate indication for antimicrobial therapy.

Composite clinical outcome included presence of hospital readmission, death, or transfer to critical care within 14 days of urine collection.

Discussion

Many hospitals report UC growth of 104 CFU/mL or greater from inpatients, based on evidence that it confers improved sensitivity in detecting acute cystitis in young outpatient women.5 Data are lacking regarding the risks and benefits of this threshold among hospitalized patients where ASB/C is much more prevalent.

Raising the threshold to 105 CFU/mL or greater was associated with sustained reduction in antimicrobial use for ASB/C on the order of 70 fewer treatment courses per year without evidence of undertreatment of UTI. Based on studies suggesting that 20% of hospitalized patients receiving antibiotic therapy experience an adverse drug event,6 we estimate that 14 adverse drug events were averted annually.

The present study was conducted in a single academic institution in Canada and may not apply to all acute care settings. This intervention only addresses approximately one-third of ASB/C cases among hospitalized patients and should be combined with other improvement strategies.1 Although the retrospective evaluation could have overestimated ASB/C because of incomplete symptom documentation, the low volume of telephone requests received confirmed that clinicians had a low pretest suspicion of UTI in these cases.

The simple change of raising the threshold for identifying potential urinary pathogens may avert nearly a third of ASB/C treatment among hospitalized patients and could have scalable impact on improving antimicrobial use in acute care hospitals.

References

- 1.Daniel M, Keller S, Mozafarihashjin M, Pahwa A, Soong C. An implementation guide to reducing overtreatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(2):271-276. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwon JH, Fausone MK, Du H, Robicsek A, Peterson LR. Impact of laboratory-reported urine culture colony counts on the diagnosis and treatment of urinary tract infection for hospitalized patients. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;137(5):778-784. doi: 10.1309/AJCP4KVGQZEG1YDM [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith MA, Lamb MJ, Baillie L, Simor A, Leis JA. Clinical significance of low colony-count urine cultures among hospitalized inpatients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018;39(4):488-489. doi: 10.1017/ice.2017.324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of healthcare-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/PDFs/pscManual/7pscCAUTIcurrent.pdf. Accessed January 2018.

- 5.Stamm WE, Counts GW, Running KR, Fihn S, Turck M, Holmes KK. Diagnosis of coliform infection in acutely dysuric women. N Engl J Med. 1982;307(8):463-468. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198208193070802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamma PD, Avdic E, Li DX, Dzintars K, Cosgrove SE. Association of adverse events with antibiotic use in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1308-1315. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]