Abstract

This study assesses primary care spending as a proportion of total spending among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries by using narrow and broad definitions of primary care practitioners and services.

Greater health system orientation toward primary care is associated with higher quality, better outcomes, and lower costs.1,2 Recent payment and delivery system reforms emphasize investment in primary care,3 but resources presently devoted to primary care have not been estimated nationally.4,5 In this study, we calculated primary care spending as a proportion of total spending among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries and describe variation by beneficiary characteristics and by state.

Methods

We analyzed spending for all Medicare beneficiaries 65 years or older with 12 months of Parts A and B fee-for-service medical coverage and Part D prescription coverage in 2015. We used the Master Beneficiary Summary File (MBSF) Base segment (enrollment and demographic data), MBSF Cost and Utilization segment (total medical and prescription spending), and MBSF Chronic Conditions segment (27 chronic conditions); Carrier File (professional claims) and Outpatient File (professional claims absent from the Carrier File including critical access hospitals, rural health centers, federally qualified health centers, and electing teaching amendment hospitals); and Medicare Data on Provider Practice and Specialty File (practitioner characteristics). This study was approved by the RAND Corporation Human Subjects Protection Committee with waiver of informed consent for analysis of deidentified data.

We measured primary care spending by using narrow and broad definitions of primary care practitioners (PCPs) and primary care services.5 The narrow PCP definition included family practice, internal medicine, pediatric medicine, and general practice; the broad PCP definition also included nurse practitioners, physician assistants, geriatric medicine, and gynecology. Both definitions excluded hospitalists.

The narrow primary care services definition included Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes on professional claims, including evaluation and management visits, preventive visits, care transition or coordination services, and in-office preventive services, screening, and counseling; the broad definition included all professional services billed by PCPs. We excluded facility fees for outpatient primary care services billed in the Carrier File and did not include services ordered but not performed directly by PCPs (eg, tests and medications).

We measured primary care spending as a percentage of total medical and prescription spending nationally, by beneficiary characteristics, and by state. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Results were reported as 2015 US dollars and Spearman correlation coefficients. We reported 2-tailed P < .05 as statistically significant.

Results

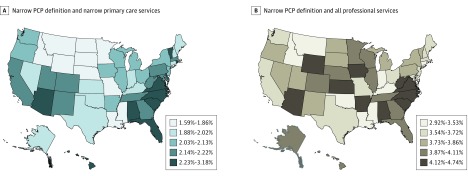

Among 16 244 803 beneficiaries, primary care represented 2.12% of total medical and prescription spending for the narrow definitions of PCPs and primary care services and 4.88% for the broad definitions (Table). For all definitions, primary care spending percentages were lower among beneficiaries who were older (eg, 1.76% for beneficiaries 85 years or older vs 2.12% for all beneficiaries, using the narrow definition), black (1.76%) or North American Native (1.51%), dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (1.64%), and who had chronic medical conditions (except hyperlipidemia). Primary care spending percentages varied by state (Figure), from 1.59% in North Dakota to 3.18% in Hawaii for the narrow health care provider and service definitions and from 2.92% in the District of Columbia to 4.74% in Iowa for the narrow health care provider and broad service definition. States’ primary care spending percentages were not significantly correlated with per capita PCP headcounts6 (Spearman correlation coefficients 0.10 [P = .47] and −0.07 [P = .61], respectively).

Table. Patient Characteristics and Primary Care Spending Among Fee-for-Service Medicare Beneficiaries in 2015.

| Characteristic | Primary Care Practitioner Definition, % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Narrowa | Broadb | |||

| Narrow Primary Care Servicesc | All Professional Services | Narrow Primary Care Servicesc | All Professional Services | |

| Age, y | ||||

| 65-69 | 2.28 | 3.92 | 2.92 | 5.15 |

| 70-74 | 2.28 | 3.97 | 2.86 | 5.12 |

| 75-79 | 2.19 | 3.90 | 2.71 | 4.96 |

| 80-84 | 2.03 | 3.73 | 2.52 | 4.71 |

| >85 | 1.76 | 3.38 | 2.24 | 4.34 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 2.15 | 3.87 | 2.60 | 4.82 |

| Female | 2.11 | 3.74 | 2.72 | 4.92 |

| Race/ethnicityd | ||||

| White | 2.13 | 3.82 | 2.70 | 4.96 |

| Black | 1.76 | 3.28 | 2.21 | 4.15 |

| Asian | 3.04 | 4.73 | 3.35 | 5.30 |

| Hispanic | 2.18 | 3.70 | 2.57 | 4.42 |

| North American Native | 1.51 | 3.02 | 2.16 | 4.23 |

| Other | 2.61 | 4.25 | 2.99 | 4.99 |

| Unknown | 2.61 | 4.27 | 3.14 | 5.31 |

| Dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid | ||||

| Yes | 1.64 | 3.23 | 2.16 | 4.23 |

| No | 2.32 | 4.02 | 2.88 | 5.14 |

| Chronic conditions | ||||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 1.30 | 2.90 | 1.66 | 3.70 |

| Alzheimer disease | 1.40 | 2.99 | 1.99 | 4.11 |

| Alzheimer disease and related disorders or senile dementia | 1.40 | 3.02 | 1.90 | 4.03 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.54 | 3.15 | 1.95 | 4.04 |

| Cataract | 2.07 | 3.74 | 2.61 | 4.81 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.53 | 3.11 | 1.94 | 3.99 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1.66 | 3.32 | 2.12 | 4.25 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.49 | 3.09 | 1.90 | 3.95 |

| Diabetes | 1.91 | 3.55 | 2.37 | 4.47 |

| Glaucoma | 2.06 | 3.66 | 2.56 | 4.65 |

| Hip or pelvic fracture | 1.08 | 2.54 | 1.46 | 3.41 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 1.79 | 3.40 | 2.24 | 4.33 |

| Depression | 1.73 | 3.33 | 2.28 | 4.41 |

| Osteoporosis | 1.88 | 3.54 | 2.40 | 4.59 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis | 1.97 | 3.61 | 2.49 | 4.68 |

| Stroke or transient ischemic attack | 1.55 | 3.19 | 1.99 | 4.10 |

| Cancer | ||||

| Breast | 1.75 | 3.20 | 2.27 | 4.23 |

| Colorectal | 1.48 | 3.06 | 1.86 | 3.89 |

| Prostate | 1.85 | 3.41 | 2.23 | 4.28 |

| Lung | 1.12 | 2.49 | 1.42 | 3.18 |

| Endometrial | 1.54 | 3.00 | 2.10 | 4.19 |

| Anemia | 1.76 | 3.35 | 2.22 | 4.31 |

| Asthma | 1.66 | 3.32 | 2.11 | 4.26 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 2.13 | 3.80 | 2.66 | 4.86 |

| Benign prostatic hyperplasia | 2.04 | 3.76 | 2.46 | 4.67 |

| Hypertension | 2.06 | 3.71 | 2.58 | 4.75 |

| Hypothyroidism | 1.98 | 3.64 | 2.51 | 4.68 |

| Primary care spending | ||||

| Per beneficiary, $ | 308.32 | 550.62 | 387.79 | 708.23 |

| Fraction of total medical and prescription spendinge | 2.12 | 3.79 | 2.67 | 4.88 |

Includes family practice, internal medicine, pediatric medicine, and general practice.

Includes family practice, internal medicine, pediatric medicine, general practice, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, geriatric medicine, and gynecology.

Includes Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes on professional claims including evaluation and management visits, preventive visits, care transition or coordination services, and in-office preventive services, screening, and counseling.

All race/ethnicity variables in this analysis are from the Master Beneficiary Summary File (variable name BENE_RACE_CD).

In 2015, for the selected population, mean per capita total medical and prescription spending was $14 519 ($11 596 in medical spending and $2913 in prescription spending).

Figure. Primary Care Spending as a Proportion of Total Medical and Prescription Spending Among Fee-for-Service Medicare Beneficiaries.

Definitions of primary care practitioner (PCP) and primary care services are given in the Methods section.

Discussion

Primary care spending represented a small percentage of total fee-for-service Medicare spending and varied substantially across populations and states. Primary care spending percentages were lower among medically complex populations and were not correlated with state-level PCP headcounts, which suggests that headcounts might mismeasure primary care investment. Our estimates of primary care spending percentages in Medicare were lower than previous estimates among a convenience sample of commercial insurers, states, and other countries4,5; these comparisons were confounded by differences in patient age, payer type, and other factors.

One limitation of this study is that our broader definitions of primary care spending may have included nonprimary care services delivered by PCPs, while our narrower definitions of primary care services may have excluded some PCPs or primary care services.

The optimal percentage of Medicare spending for primary care is unclear. Future research should evaluate effects on quality or outcomes of state efforts (eg, Rhode Island and Oregon) to institute minimum primary care spending percentages.4 Our estimates may constitute reference points for future policies across the United States.

References

- 1.Friedberg MW, Hussey PS, Schneider EC. Primary care: a critical review of the evidence on quality and costs of health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):766-772. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457-502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pham H, Ginsburg PB. Payment and delivery-system reform—the next phase. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(17):1594-1596. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1805593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koller CF, Khullar D. Primary care spending rate—a lever for encouraging investment in primary care. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(18):1709-1711. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1709538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailit MH, Friedberg MW, Houy ML. Standardizing the Measurement of Commercial Health Plan Primary Care Spending. New York, New York: Milbank Memorial Fund; 2017, https://www.milbank.org/publications/standardizing-measurement-commercial-health-plan-primary-care-spending/. Accessed March 5, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Health Workforce Area Health Resources Files (AHRF) 2015-2016. Rockville, MD. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/ahrf. Accessed March 5, 2019.