Abstract

The human eye is the organ that is able to react to light in order to provide sharp three-dimensional and colored images. Unfortunately, the health of the eye can be impacted by various stimuli that can lead to vision loss, such as environmental changes, genetic mutations, or aging. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and unfolded protein response (UPR) signaling have been detected in many diverse ocular diseases, and chemical and genetic approaches to modulate ER stress and specific UPR regulatory molecules have shown beneficial effects in animal models of eye disease. This review highlights specific eye diseases associated with ER stress and UPR activity, based on a recent symposia exploring this theme.

Keywords: achromatopsia, AMD, ER stress, glaucoma, neurodegernation, retinal degeneration, RGC, RPE, UPR, VEGF

Introduction

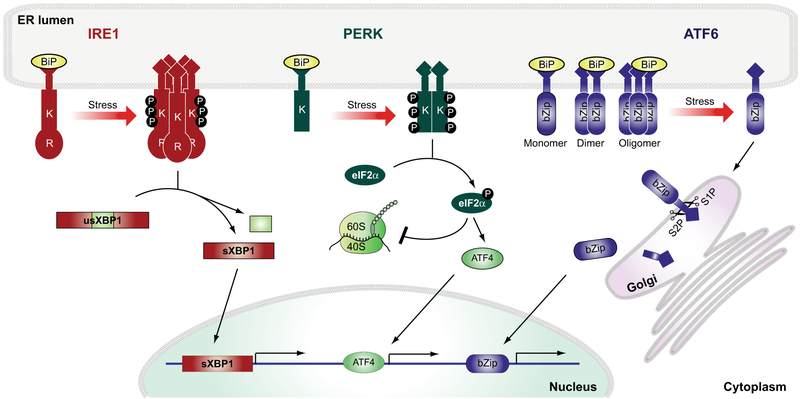

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is found in every eukaryotic cell; it is a double-membrane bound organelle facilitating a wide variety of functions, such as protein folding, free calcium storage, and lipid/sterol synthesis. ER homeostasis can be compromised by many pathological events, including protein misfolding or accumulation of mutant protein, which can lead to ER stress [1]. The ER has its own regulatory mechanism, called the unfolded protein response (UPR), that is activated in an attempt to restore ER homeostasis and to prevent further damage to the cell [2]. In mammalian cells, the UPR is regulated by inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1), PKR-like ER kinase (PERK), and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) (Fig. 1). Under unstressed conditions, activation of IRE1, PERK, and ATF6 is prevented by the binding of the ER-resident protein, binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP) also known as 78-kDa glucose-regulated protein (GRP78) or heat shock 70-kDa protein 5 (HSPA5) gene, to their N-terminal domains. Once ER stress occurs BiP dissociates and activates IRE1, PERK, and ATF6 [3-6]. These three mediators activate a comprehensive transcriptional and translational signaling program; on one side, protein translation is slowed down, but on the other side proteins are being upregulated that belong to the folding machinery of the ER and the endoplasmic-reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) to increase degradation events [2].

Fig. 1.

Unfolded protein response signaling pathways. Schematic Illustration of the three unfolded protein response signaling pathways, comprised of inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1), PKR-like ER kinase (PERK), and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6). Under unstressed conditions, the activity of these three UPR inducers is prevented by BiP binding. Ones ER stress occurs BiP dissociates and activates IRE1, PERK and ATF6. IRE1’s luminal domain is coupled to the cytosolic kinase (K) and endoribonuclease (R) domains. ER stress leads to IRE1 oligomerization, transautophosphorylation, and the unconventional splicing of X-box binding protein-1 (usXBP1) mRNA to generate spliced XBP1 (sXBP1). The PERK protein bears a luminal domain that is linked to a kinase domain. PERK activation causes its dimerization and phosphorylation of the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 subunit alpha (eIF2α), leading to attenuation of global protein translation. ATF6 migrates as a monomer from the ER to the Golgi compartment upon activation. Two independent proteases (S1P and S2P) cleave ATF6 to generate a potent transcription factor that contains a bZip domain to bind to DNA to upregulate its downstream targets.

IRE1 is a key regulator of the UPR [2]. As an ER-resident transmembrane protein, IRE1 has a luminal domain, which is connected to its cytosolic kinase and endoribonuclease domain [Fig. 1, (K) and (R), respectively] [7-9]. In response to ER stress, IRE1 oligomerizes, resulting in the activation of its kinase domain leaving IRE1 autophosphorylated that ultimately leads to the activation of its RNase domain and the removal of an inhibitory intron from the mRNA of unspliced XBP-1 (usXBP1), generating the potent transcription factor spliced XBP1 (sXBP1) (Fig. 1) [10,11]. Transcriptional target genes of sXBP1 include several genes of the ERAD pathway [12,13].

The PERK branch of the UPR is responsible for a different response to ER stress [2]. In the presence of ER stress, PERK oligomerizes, which activates its cytosolic kinase domain leading to the inhibition of the ternary translation initiation complex (Fig. 1K) [14]. Inhibition of global protein translation is facilitated by PERK kinase activity by phosphorylating elongation initiation factor 2 alpha (eIF2α), which is an essential step to reduce the load of newly synthesized peptides in the ER and to alleviate ER stress to restore ER homeostasis [14,15]. Under prolonged ER stress, PERK signaling regulates a cell death program by upregulating proapoptotic transcriptional activators, activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein homologous protein (CHOP) (Fig. 1) [16,17].

ATF6 is a N-linked glycosylated type 2 transmembrane protein able to exist as a monomer and oligomer, and also as heteromeric complexes with other ER proteins through its ability to form intra- and intermolecular disulfide bonds (Fig. 1) [18,19]. In response to ER stress, ATF6 is reduced to its monomeric confirmation and translocates from the ER to the Golgi compartment using COP II vesicles where site 1 (S1P) and site 2 (S2P) proteases cleave ATF6 in the transmembrane domain resulting in the release of ATF6’s cytosolic domain [20-22]. ATF6 transcriptional activity arises from its cleaved cytosolic domain, which contains a basic leucine zipper (bZIP)-domain that locates to the nucleus to upregulate ATF6 target genes, such as GRP78/BiP [11,13].

This review will provide an overview on what currently is known on the involvement of UPR signaling pathways in various eye diseases.

Chapter 1: Diabetic retinopathy – interference of UPR signaling events as potential treatment and prevention of DR disease pathologies

Diabetic eye disease, also known as diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a medical condition caused by damage to the retina so severe that it is described as the leading cause of blindness. DR is defined as a common vascular complication of diabetes with hallmarks of vascular dysfunction, neovascularization, increased permeability, inflammation, and vascular degeneration.

Yan et al. [23], have shown in one of their previous studies that P58IPK/DNAJC3, an ER stress-related protein, is able to bind to PERK and therefore prevents the phosphorylation of the α-subunit of its downstream target eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 (eIF2α). Several studies since have demonstrated that P58IPK plays a protective role during ER stress [23,24]. Using human retinal capillary endothelial cells (HRCECs), Li and colleagues investigated the relationship between ER stress and P58IPK [25]. It was demonstrated that when endogenous expression of P58IPK was increased by transfections, expression of ATF4, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) was decreased in HRCECs when ER stress was induced. It is suggested that P58IPK is able to down-regulate the activity of the ATF4 and VEGF pathways during ER stress. It was additionally shown that increased expression of P58IPK resulted in decreased levels of CHOP in HRCECs, associated with the decline of ER stress-related apoptotic events. Furthermore, it is suggested that enhanced P58IPK expression may reduce retinal blood vessel damage, since VEGF expression was also reduced in the presence of elevated P58IPK expression. P58IPK is therefore thought to be responsible for the inhibition of ER stress in endothelial cells of retinal blood vessels [25].

Vascular endothelial growth factor is a dimeric glycoprotein and a potent endothelial mitogen, and is thought to promote angiogenic growth of new blood vessels by regulating the proliferation, migration, and tubule formation of endothelial cells [26-28]. VEGF is a key player in pathology of retinal diseases, such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD), retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), sickle cell retinopathy (SCR), and retinal vascular occlusion (RVO) (reviewed in [29]). VEGF also plays a key role in DR pathologies [30,31], and its expression is regulated by UPR signaling [32].

One of the first studies that demonstrated a link between ER stress and the upregulation of intracellular VEGF expression as well as VEGF secretion was performed by Abcouwer and colleagues in 2002 [33]. Using the human retinal pigment epithelial cell line (ARPE-19) and a wide variety of ways to induce ER stress, such as amino acid deprivation and glucose deprivation (tunicamycin, brefeldin A, calcium ionophore A23187, thapsigargin), Abcouwer et. al. identified a significant increase in VEGF mRNA levels of 1.3- to 6-fold and 8- to 10-fold, respectively. The increased presence of VEGF mRNA levels was correlated with an increase in GRP78 mRNA levels under the same conditions [33]. In a different study, Li et. al. reported in an in vitro study that ER stress is increased in Akita mouse retinas, which is a genetic model of type 1 diabetes [34]. Using intravitreal injections of tunicamycin to induce ER stress in the retina, increased retinal VEGF expression was observed [34]. Additionally, it was reported that exposure of ER stress inducers, tunicamycin and thapsigargin, to vascular endothelial cells as well as Müller cells resulted in significant upregulation of VEGF expression [34-36]. Li and colleagues have further shown that ER stress induction leads to a significant induction of inflammatory molecules in diabetic retinas. Interestingly, when performing ER stress inhibitory experiments, amelioration of inflammation was observed in cultured human retinal endothelial cells that experience hypoxia – the findings that were confirmed using a diabetic animal model [34]. These results are also supported in additional animal models of type 1 and type 2 diabetes [37-40].

The activation of the transcription factor ATF4 through the PERK branch of the UPR on ER stress or high-glucose levels in retinal Müller cells (Fig. 2) has been shown to be essential for the induction of hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) and VEGF secretion [41]. Furthermore, genetic inactivation of ATF4 greatly impacted diabetic-induced retinal inflammation and vascular leakage attenuation [35], supporting a role for ATF4 in retinal inflammation and endothelial barrier dysfunction.

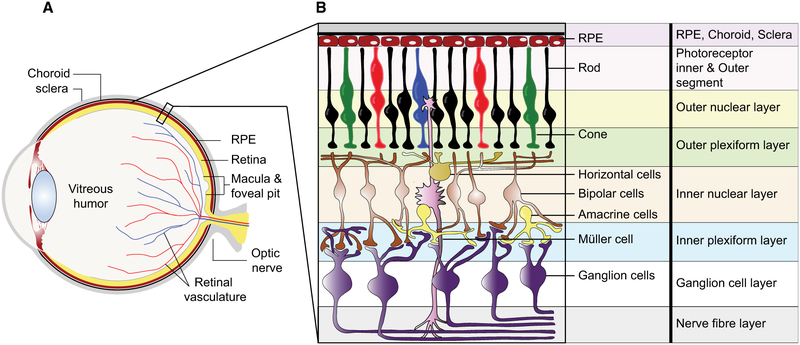

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of the human eye and retina. (A) Anatomy of the human eye with (B) detailing the structure and cell components of the human retina.

A strong correlation between the distinct activation of UPR signaling events and the duration of diabetes has been reported. This fact is strongly supported by a research study performed by Yan and colleagues in 2012 [40]. A diabetic rat model was established by intraperitoneal injections of streptozotocin (STZ), which was used to analyze 89 ER stress-related factors by quantitative RT-PCR [40]. All 89 ER stress genes were expressed at both first and third month after development of diabetes, but significant changes were only detected in the expression of 13 genes and 12 genes in the first and third month after development of diabetes, respectively, when compared to nondiabetic animals [40]. Only two genes were identified that showed significant changes at both time point, HERP1 (homocysteine-responsive endoplasmic reticulum-resident ubiquitin-like domain member 1 protein) and ERdj4 (DNAJB9, DnaJ heat shock protein family (Hsp40) member B9) [40].

Research performed to date widely suggests the differential involvement of UPR signaling in retinal cells and tissues using multiple diabetes models [42-44]. It appears that all branches of the UPR are activated to some degree in diabetic retinas [34,35,37-39,41]. However, there are variations between the studies about the activation status of the individual UPR pathways, which could be due to the choice of retinal and diabetic animal model, severity of diabetes, diabetes development, time point of study, and methods of UPR pathway analysis.

Chapter 2: Affecting UPR signaling events as treatment of glaucoma

Glaucoma is a group of optic neuropathies and the second leading cause of irreversible blindness in the world affecting approximately 70 million people [45,46]. It is mainly characterized by the degeneration of retinal ganglion cell (RGC) axons resulting in vision loss (Fig. 2). Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is the most common form of glaucoma and accounts approximately 70% of all cases [47]. POAG is usually accompanied by an elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), one of the major risk factors. Elevated IOP occurs when the outflow resistance of the aqueous humor, which is produced by the ciliary bodies and normally empties through the trabecular meshwork (TM), is increased and the liquid is no longer able to drain through the TM structures. The mechanisms that cause increased outflow resistance in the TM are not well understood yet.

A growing number of studies implicate ER stress in the TM as a cause for increase in IOP, and that reduction of ER stress can prevent ocular pathologies in glaucoma mouse models [48,49]. In human glaucomatous TM cells, elevated levels of ER stress-induced proteins, including GRP78, GRP94, and CHOP have been detected [50]. These results support the findings obtained in mouse models and point to chronic ER stress in human glaucomatous TM. Interestingly, little Xbp1 splicing or phosphorylated eIF2a were seen, which suggest dysregulated UPR signaling in glaucomatous TM cells compared to wild-type cells [50]. By contrast, genetic studies reveal that CHOP induction may play causal roles in glaucoma damage. Zode and colleagues demonstrated that deletion of CHOP protects against ER stress-mediated IOP elevation in glucocorticoid-induced ocular hypertension mouse models, and Hu and colleagues pointed out that the deletion of CHOP promotes RGC survival in mouse models of optic nerve crush and ocular hypertension [42].

Mutations in the myocilin gene (MYOC) are known to be the most common genetic cause of POAG and autosomal dominant juvenile-onset open-angle glaucoma [47,51-54]. Myocilin is expressed in many ocular tissues including TM cells, but its function is poorly understood. Recent studies on a transgenic glaucoma mouse model (Tg-MYOCY437H) expressing the human mutated form of myocilin found increase in IOP in these mice already at an age of 3 months [48]. Zode and colleagues also showed that the topical administration of 4-phenylbutyrate (PBA) on the cornea significantly reduces the elevated IOP levels in those mice. Animals treated with PBA preserved pattern electroretinogram (PERG) amplitudes similar to control littermates and showed improved myocilin secretion as well as reduced ER stress in TM cells [48]. These results suggest that PBA, a chemical chaperone, enhances the folding of mutant myocilin and its secretion into the aqueous humor thereby preventing its accumulation in the TM and the evocation of ER stress. Thus, topical application of PBA eye drops could serve as a new therapy option for patients with myocilin-associated POAG.

It would provide great evidence if additional data could be provided to demonstrate that POAG is strongly associated with myocilin gene mutations, mice research studies could demonstrate a connection between POAG and mutation in UPR genes. Increasing ER stress due to potential dysfunction and/or upregulation of different UPR components seems to be another reason of IOP and for the development of POAG. Hence, to study the genetic background of this disease in more detail might reveal deeper understanding in the development of one of the world′s leading causes of blindness.

Chapter 3: Involvement of ER stress in retinal degeneration

Inherited retinal disorders (IRDs) form a genetically and clinically very heterogeneous group of diseases leading to severe visual impairments. One well-known IRD is retinitis pigmentosa (RP). RP refers to a very large number of genetically and phenotypically heterogeneous IRDs affecting more than one million people worldwide [55,56]. RP is primarily characterized by progressive rod photoreceptor degeneration, night blindness, and progressive constriction of the visual field, also known as tunnel vision. Secondarily, cone photoreceptors die resulting in a complete vision loss in later stages of the disease. Another well-studied IRD is Lebers congenital amaurosis (LCA). It is the most severe form of IRD, with congenital or early childhood blindness. Symptoms of LCA include nystagmus, impaired or absent papillary response. The protein that is linked to the development of LCA is tubby-like protein 1 (TULP1), which is a protein coding gene. Proteins of the TULP family share a conserved C-terminal domain of approximately 200 amino acid residues. TULP1 is also known as a photoreceptor specific protein that is involved in the transport of visual cascade proteins as rhodopsin, which is synthesized in the photoreceptor inner segment (IS) and transported through the connected cilium into the outer segment (OS) [57-60] (Fig. 2). TULP1 has been localized to the IS of the photoreceptor cell, closely to other parts of the biosynthetic machinery as the ER or the Golgi apparatus. Here, it functions as a chaperone or an adaptor protein linking vesicles with their proper motor proteins for effective cargo transport to the membrane [57-59]. Previous studies have shown that mutations in TULP1, among mutations in other genes, are the underlying cause of an early-onset form of autosomal recessive RP (arRP) and LCA [57-59]. Many missense, splice site, and stop mutations have been identified in TULP1 [61,62]. Lobo and colleagues demonstrated that missense mutations in TULP1 produce misfolded TULP1 protein accumulating in the ER and causing ER stress [63]. Immunohistochemical analyses show that wild-type TULP1 can be mainly found in the plasma membrane and cell processes of immortalized RPE cells, whereas mutant TULP1 predominantly accumulates in a spot-like pattern in the cytoplasm resembling that of the ER. Elevated levels of different ER markers, such as BiP, PERK, and XBP1 or XBP1s, could be detected in cells transfected with the mutant TULP1 in comparison to wild-type TULP1 [63]. Furthermore, overexpression of mutant TULP1 causes higher cell death rates as well as elevated CHOP levels compared to controls [63]. In addition, in vivo studies showed that mutant TULP1 accumulates in the ER of the mouse retina. These results suggest that various signaling components of the UPR become activated in retinal cells expressing mutant TULP1, promoting cell death, and may underlie the photoreceptor degeneration in TULP1-associated RP. Hence, mutated TULP1 is a prototype par excellence that misfolded proteins are retained in the ER of photoreceptor cells instead of being transported into the OS leading to ER stress and cell death. In this context, another well-known example is the misfolding of rhodopsin protein. Mice and rats carrying the P23H mutation are wildly used as RP animal models, expressing misfolded and nonfunctional rhodopsin, which similar to mutated TULP1 is retained in the ER and can no longer be transported into the OS.

Photoreceptor cells in the retina are constantly producing soluble and membrane proteins, for example, components of phototransduction machinery, that are destined to the cell surface or the OS disks (Fig. 2). Many of these proteins are synthesized and folded in the ER. If the retina is exposed to conditions that cause disturbance in ER homeostasis, it could induce ER stress in the photoreceptor cells and lead to retinal degeneration. These conditions include, but not limited to, expressing mutant proteins in the retina, exposing the eyes to bright light, and aging [64-69]. Studies performed over the past decade have implicated that ER stress is involved in retinal degenerative diseases [64,66-68,70]. Using the ERAI mouse GFP reporter line, it has been demonstrated that UPR is activated in mice photoreceptors expressing T17M or P23H mutant rhodopsin providing evidence for ER stress in these photoreceptors [64,65,67]. Since UPR signaling can restore ER homeostasis (Fig. 1), targeting UPR signaling may enhance retinal health or delay retinal degeneration.

In cell culture studies, overexpression of the BiP/Grp78 ER chaperone in cells expressing mutant P23H rhodopsin alleviates ER stress and reduces apoptosis [71]. Gorbatyuk et al. also demonstrated that subretinal gene delivery of BiP/Grp78 through adeno-associated virus type 5 (AAV5) to transgenic rats expressing P23H rhodopsin reduced the expression of a proapoptotic gene, Chop, and partially restored retinal function in the P23H transgenic rats [71]. Recently, it has been shown that overexpressing ATF4 accelerates retinal degeneration in mice expressing T17M mutant rhodopsin [72]. However, knocking down ATF4 in mice expressing T17M mutant rhodopsin prevented the T17M mice from losing their retinal functions and retinal integrity [72]. Interestingly, when Chop was ablated from the mice expressing either T17M or P23H rhodopsin, the retinal function was not rescued and the mice still underwent severe retinal degeneration, suggesting that Chop was dispensable in retinal degeneration of these mouse models [64,73-75]. Genetic and chemical targeting of other UPR components and signaling pathways may reveal new ways to alleviate ER stress in retinal degenerative diseases.

Chapter 4: ATF6α, UPR mediator, and inherited retinal dystrophies gene

As described in chapter 3, IRDs constitute a large group of genetically inherited retinal degenerative disorders and can be classified as to whether they cause degeneration of rod and/or cone photoreceptor cells (Fig. 2). To date, approximately 250 inherited retinal dystrophy genes have been identified (Retinal Information Network http://www.sph.uth.tmc.edu/RetNet/). Achromatopsia is characterized by cone photoreceptor dysfunction and eventual degeneration of cone photoreceptors, whereas cone-rod dystrophy (CRD) is characterized by progressive loss of cone function; followed by loss of rod photoreceptor function (Fig. 2).

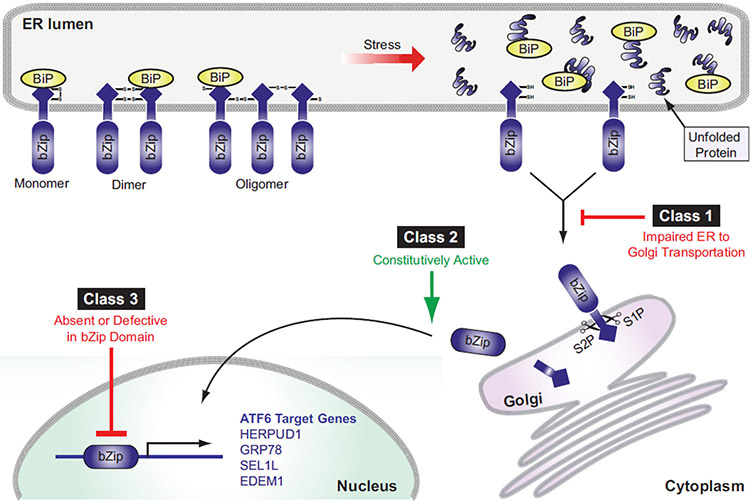

Using next-generation whole-exome sequencing, we recently discovered autosomal recessive mutations presented in the activating transcription factor 6 α (ATF6α) gene in patients with achromatopsia and CRD [76-78]. ATF6α is a glycosylated transmembrane protein found in the ER known for its function in the ATF6-linked UPR pathway [19] (Fig. 1/3). In response to ER stress, ATF6α is transported from the ER to the Golgi apparatus where site 1 and site 2 proteases cleave ATF6α to release the cytosolic domain of ATF6α, which is a basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor [19]. The cleaved cytosolic domain of ATF6α then locates to the nucleus where it binds to DNA and transcriptionally upregulates downstream target genes, such as ER protein folding chaperones and enzymes [18,19,79,80] (Fig. 1/3).

The identified ATF6α mutations span the entire coding region of ATF6α gene. The changes include missense, nonsense, splice-site, and small frame-shifting deletions, insertions and duplications mutations. These mutations were classified into three different functional classes based on the effect and the location of the mutation [77] (Fig. 3). Class 1 ATF6α mutations code for mutant ATF6α that exhibit impaired trafficking from the ER to the Golgi apparatus and, therefore, demonstrate reduced proteolysis to release the cytosolic domain under ER stress conditions [77]. Class 2 ATF6α mutations code for truncated ATF6α containing fully functional bZIP and transcription activation domains. These truncated ATF6α mutants are able to constitutively activate downstream targets [77]. Class 3 ATF6α mutations code for ATF6α mutants that have absent or defective bZIP domain, resulting in the loss of transcriptional activity [77].

Fig. 3.

Classification of ATF6 mutations. Full length ATF6 can be present as a monomer, dimer, or oligomer using disulfide bond formations, once UPR signaling is activated BiP dissociates, and reduced monomeric ATF6 traffics from the ER to the Golgi compartment (see Fig. 1). Class 1 ATF6 mutations are trafficking mutations that show an impairment of translocation from the ER to the Golgi apparatus. Class 2 mutations of ATF6 present a fully intact cytosolic domain of ATF6 and show constitutive transcriptional activator function. Class 3 ATF6 mutations demonstrate a nonfunctional bZip domain and fail to bind and upregulate ATF6 specific targets.

The identification of ATF6α as a novel retinal dystrophy gene reveals that ATF6α has a crucial role in human retinal (foveal) development and cone photoreceptor function (Fig. 2). Intriguingly, despite ATF6α ubiquitous expression, mutations in ATF6α solely manifest in a cone photoreceptor phenotype in human

Chapter 5: Functional role of ER stress during cellular senescence and pathological angiogenesis

Senescence is a cellular state that cells adopt upon exposure to DNA damage, telomere shortening, and many other cellular stresses. Increased numbers of senescence cells are a feature of the normal aging process that results in aggravation of tissue function [81-83]. Cellular senescence is also a common feature in complex physiological processes, such as embryogenesis and tissue repair [84-87]. Biochemical and/or inflammatory stressors can compromise the function of cells in our nervous system, such as breakdown of the vascular system or a part thereof as witnessed in vascular retinopathies (DR and ROP) [88]. The retinal neurons directly exposed to the degenerating vasculature in ischemic retinopathies are retinal ganglion cells (RGC) (Fig. 2). RGCs require a stable metabolic supply for proper function. One of the central questions in ischemic retinopathies is how can retinal ganglion cells escape ischemia-induced cell death. A recent research study from Oubaha et al. [89] have provided insight into why retinal neurons survive in ischemic retinopathies despite compromised metabolic supply and explored the function of cellular senescence. When a cell undergoes senescence, it acquires a permanent state of cell cycle arrest, in which cells remain viable [90]. Oubaha et al. [89] found that retinal ischemia can trigger cellular senescence to protect retinal cells, which enables retinal cells to survive periods of limited metabolic supply and to escape hypoxia-associated cell death in a mouse model of ischemic retinopathy. Interestingly, using transcriptome analysis combined with loss-of-functions genetics, Oubaha’s results indicated that those cells require the activity of the endoribonuclease domain of IRElα to promote senescence and adopt a senescence-associated secretory Phenotype (SASP) [89]. The presence of SASP-associated cytokines, such as plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-8 (IL-8), and VEGF were found to be present in the vitreous humor of patients suffering from proliferative DR. Furthermore, they identified a clinical relevance of SASP inhibition using metformin, a widely used biguanide antidiabetic drug known to reduce SASP without interfering with the growth arrest program [91]. They demonstrated that intravitreal injection of metformin into mice abolished SASP, decreased ER stress, and reduced retinal neovascularization and pathological retinal angiogenesis [89].

Additional research performed by Binet and colleagues demonstrates that failure of the reparative angiogenesis system in the ischemic retina is temporally and spatially linked to ER stress [92]. PERK and IRE1α activation (Fig. 1) were found in hypoxic/ischemic retinal ganglion cells and linked to the activation of signaling cascades of the angiostatic response in those regions [92]. Authors further identified that the endoribonuclease domain of IRE1α degrades netrin-1, which normally play an essential role in myeloid-dependent revascularization. Inhibition of IRE1α or treatment with netrin-1 showed enhanced retinal vascular regeneration leading to a relief of the hypoxic stimulus and prevention of destructive neovascularization [92]. The degradation of netrin-1 through IRE1α activation by persisting neuronal ER stress could underlie the vascular regeneration and direct regulation of reparative angiogenesis seen in ischemic retinas.

Chapter 6: UPR signaling in retinal ganglion cells

RGCs play an essential role in the processing of visual information, which they receive from the photoreceptors that passes on the information to bipolar and retina amacrine cells before it reaches the RGCs (Fig. 2). The axons of RGCs form the optic nerve; they are the only type of retinal neuron that is able to directly pass visual information to the brain, which makes them extremely vulnerable to axon damage, resulting in vision loss due to optic neuropathy [93]. Traumatic optic nerve injury followed by RGC loss is a common feature of head injuries caused by falls or traffic accidents. It has been shown in rodents that the majority of RGCs undergo cell death at approximately 2 weeks after intraorbital optic nerve injury [94-96].RGC loss as hallmark of optic neuropathy, other than optic nerve trauma, is also seen in glaucoma [97-102]. Apoptosis has been described as one of the leading causes of RGC loss in these diseases [97-101,103]. In the search for therapeutic targets, it becomes apparent that targeting apoptotic effectors may not be a valuable approach since RGC death most likely occurs at the end stage of the disease, which suggest that identifying upstream effectors (before RGCs are terminally committed to apoptosis) is more fruitful. In 2012, Hu and colleagues employed an optic nerve crush model known to result in loss of the majority of RGC [104]. They identified that distinct pathways of the ER stress response are activated in axotomized RGCs in this optic nerve crush model [104]. Furthermore, they found that optic nerve injury causes transcriptional upregulation of CHOP. CHOP knockout mice showed dramatically increased RGC survival in their optic nerve crush model [104]. Also, overexpression of spliced XBP1 using adeno-associated virus in CHOP KO mice further enhanced RGC survival after optic nerve injury [104]. These studies suggest that UPR signaling pathways may be attractive therapeutic targets to promote RGC survival in optic neuropathies.

Conclusions and future directions

Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the activation of the UPR signaling response are a well-known feature in many neurodegenerative diseases; under various physiological conditions, ER stress can induce apoptotic cell death leading to neuronal cell death in the brain and retina [69,105-112]. Targeting UPR signaling pathways at various stages is thought to create an opportunity to support cell survival events, prevent neuronal cell loss, and hence create treatment for neuronal diseases.

Patients suffering from diabetes have a profound chance to develop DR, which is the leading cause of blindness caused by the loss of neural and vascular retinal cells. Yan and colleagues have successful demonstrated that inhibition of PERK, prevents the phosphorylation of its downstream target eIF2α resulting in the inhibition of apoptotic cell death in endothelial cells of retinal blood vessels [23,25]. It is further thought that the downregulation of VEGF would take preventive measures in the development and advancement of DR pathologies [25]. These findings are promising but as the authors stated further clarification is needed to precisely determine how P58IPK correlates with the VEGF signaling pathway under ER stress conditions. Additional in vivo models are required to support their research findings. It would also be valuable to gain insights on how P58IPK is regulated during DR pathologies and how it could be addressed as direct target for potential treatments in the prevention of neuronal cell death.

One of the biggest challenges in the development of DR treatments is that patient that suffer from diabetes go through different disease stages, which makes it more challenging to identify a protein that can be directly target for disease treatments or prevention. This complex problem was addressed in a study from Yan et al. in 2012 [40]. Researchers studied the correlation between the activation of certain ER stress genes and the duration of diabetes. A total of 89 genes were analyzed at two time points of 1- and 3-month old diabetic mice. Of all genes analyzed, they identified that various ER stress genes are upregulated at the two different time points. However, only two of them were consistently elevated at both time point, named HERP1 and ERDj4 [40]. The very important message from this valuable study is that there is clearly a change in the expression profile of ER stress genes and UPR signaling events throughout disease development and progression. To develop effective targets to treat DR, researchers have to gain continuous insights on gene expression profiles throughout disease progression to be able to develop a therapy that can directly target an ER stress event that has the biggest potential as DR treatment.

Animal models are invaluable tools to study retinal diseases, but in some instances, other research models are required to gain a deeper understanding on how eye developmental is linked to retinal disease. Mutations in ATF6α have been linked to the development of achromatospia [76-78]. Recently, a new role for ATF6α signaling in early stem cell differentiation was identified [113]. It was shown that the activation of ATF6α during stem cell differentiation resulted in the acceleration of differentiation events toward the mesodermal lineage generating functional endothelial cells that were able to undergo in vitro angiogenesis to form blood vessels; ATF6α additionally stimulated the loss of pluripotency [113]. In the same study, ATF6α was found to support the growth and maturation of the ER without activating a comprehensive ER stress responds. It is now questioned if impairment or lack of functional ATF6α could cause the development of immature ER in cone photoreceptor cells, which could partly contribute to disease pathologies of achromatopsia. The maturation and survival of cone photoreceptor cells require the production and proper folding of cone OS proteins in the ER, lack of fully developed ER, and fully functional ATF6α may lead to the production of misfolded and nonfunctional cone proteins resulting in the death of cone photoreceptors or the under development of cone photoreceptor cells. Therefore, investigating the development of ER in cone photoreceptor cells carrying ATF6α mutation will provide more insight in how impaired ATF6α function impacts cone photoreceptor maturation.

In summary, the activation of UPR signaling events during the progression of retinal degeneration is well-known; however, it remains unclear on how exactly the ER stress response or UPR-related genes contribute to either photoreceptor cell death or the development of cone and rod cells that results in the development of retinal diseases. UPR signaling is a highly regulated cellular program that is initiated to provide a protective role, but can turn toward cell death via apoptosis in a supportive effort to protect connective tissue. The timing of IRE1, PERK, and ATF6 activation and deactivation is very sensitive and depends drastically on the severity and the extent of ER stress and its causes. It is therefore essential to gain insights on how UPR signaling mediates the fate of accumulated misfolded proteins in photoreceptor; and additionally, how the UPR regulates the switch from a prosurvival to an apoptotic response. Gaining this knowledge will be a valuable tool to address potential targets for disease treatment and/or prevention in more precise fashion.

Acknowledgements

This review was inspired by a minisymposia about ER stress in eye diseases at the 2017 ARVO meeting and 2017 ASN meeting. The authors wish to thank the speakers, participating scientists, and organizers of those sessions for their suggestions in developing this review.

Abbreviations

- AAV5

adeno-associated virus type 5

- AMD

age-related macular degeneration

- ARPE-19

human retinal pigment epithelial cell line

- arRP

autosomal recessive RP

- ATF4

activating transcription factor 4

- ATF6

activating transcription factor 6

- BiP

binding immunoglobulin protein

- bZIP

basic leucine zipper

- CHOP

CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein homologous protein

- DR

diabetic retinopathy

- eIF2α

elongation initiation factor 2 alpha

- ERAD

endoplasmic-reticulum-associated degradation

- ERdj4

DNAJB9, DnaJ heat shock protein family (Hsp40) member B9

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- GRP78

78-kDa glucose-regulated protein

- HERP1

homocysteine-responsive endoplasmic reticulum-resident ubiquitin-like domain member 1 protein

- HIF-1α

hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha

- HRCECs

human retinal capillary endothelial cells

- HSPA5

heat shock 70-kDa protein 5

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- IL-8

interleukin-8

- IOP

intraocular pressure

- IRDs

inherited retinal disorders

- IRE1

inositol-requiring enzyme 1

- IS

inner segment

- LCA

Lebers congenital amaurosis

- MYOC

myocilin gene

- OS

outer segment

- PAI-1

plasminogen activator inhibitor 1

- PBA

4-phenylbutyrate

- PERG

pattern electroretinogram

- PERK

PKR-like ER kinase

- POAG

primary open-angle glaucoma

- RGC

retinal ganglion cell

- ROP

retinopathy of prematurity

- RP

retinitis pigmentosa

- RVO

retinal vascular occlusion

- S1P

site 1 proteases

- S2P

site 2 proteases

- SASP

senescence-associated secretory phenotype

- SCR

sickle cell retinopathy

- STZ

streptozotocin

- sXBP1

spliced XBP1

- TM

trabecular meshwork

- TULP1

tubby-like protein 1

- UPR

unfolded protein response

- usXBP1

X-box binding protein-1

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

References

- 1.Hiramatsu N, Chiang WC, Kurt TD, Sigurdson CJ & Lin JH (2015) Multiple mechanisms of unfolded protein response-induced cell death. Am J Pathol 185, 1800–1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walter P & Ron D (2011) The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science 334, 1081–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gardner BM, Pincus D, Gotthardt K, Gallagher CM & Walter P (2013) Endoplasmic reticulum stress sensing in the unfolded protein response. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 5, a013169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen J, Chen X, Hendershot L & Prywes R (2002) ER stress regulation of ATF6 localization by dissociation of BiP/GRP78 binding and unmasking of Golgi localization signals. Develop Cell 3, 99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shen J, Snapp EL, Lippincott-Schwartz J & Prywes R (2005) Stable binding of ATF6 to BiP in the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Mol Cell Biol 25, 921–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sommer T & Jarosch E (2002) BiP binding keeps ATF6 at bay. Develop Cell 3, 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox JS & Walter P (1996) A novel mechanism for regulating activity of a transcription factor that controls the unfolded protein response. Cell 87, 391–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hetz C & Glimcher LH (2009) Fine-tuning of the unfolded protein response: assembling the IRE1alpha interactome. Mol Cell 35, 551–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sidrauski C & Walter P (1997) The transmembrane kinase Ire1p is a site-specific endonuclease that initiates mRNA splicing in the unfolded protein response. Cell 90, 1031–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calfon M, Zeng H, Urano F, Till JH, Hubbard SR, Harding HP, Clark SG & Ron D (2002) IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature 415, 92–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshida H, Matsui T, Yamamoto A, Okada T & Mori K (2001) XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell 107, 881–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN & Glimcher LH (2003) XBP-1 regulates a subset of endoplasmic reticulum resident chaperone genes in the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell Biol 23, 7448–7459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shoulders MD, Ryno LM, Genereux JC, Moresco JJ, Tu PG, Wu C, Yates JR 3rd, Su AI, Kelly JW & Wiseman RL (2013) Stress-independent activation of XBP1s and/or ATF6 reveals three functionally diverse ER proteostasis environments. Cell Rep 3, 1279–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harding HP, Zhang Y & Ron D (1999) Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature 397, 271–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ron D & Harding HP (2012) Protein-folding homeostasis in the endoplasmic reticulum and nutritional regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4, a013177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han J, Back SH, Hur J, Lin YH, Gildersleeve R, Shan J, Yuan CL, Krokowski D, Wang S, Hatzoglou M et al. (2013) ER-stress-induced transcriptional regulation increases protein synthesis leading to cell death. Nat Cell Biol 15, 481–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tabas I & Ron D (2011) Integrating the mechanisms of apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat Cell Biol 13, 184–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nadanaka S, Okada T, Yoshida H & Mori K (2007) Role of disulfide bridges formed in the luminal domain of ATF6 in sensing endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Cell Biol 27, 1027–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haze K, Yoshida H, Yanagi H, Yura T & Mori K (1999) Mammalian transcription factor ATF6 is synthesized as a transmembrane protein and activated by proteolysis in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Biol Cell 10, 3787–3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen X, Shen J & Prywes R (2002) The luminal domain of ATF6 senses endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and causes translocation of ATF6 from the ER to the Golgi. J Biol Chem 277, 13045–13052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schindler AJ & Schekman R (2009) In vitro reconstitution of ER-stress induced ATF6 transport in COPII vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106, 17775–17780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ye Y, Shibata Y, Yun C, Ron D & Rapoport TA (2004) A membrane protein complex mediates retro-translocation from the ER lumen into the cytosol. Nature 429, 841–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yan W, Frank CL, Korth MJ, Sopher BL, Novoa I, Ron D & Katze MG (2002) Control of PERK eIF2alpha kinase activity by the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced molecular chaperone P58IPK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99, 15920–15925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rutkowski DT, Kang SW, Goodman AG, Garrison JL, Taunton J, Katze MG, Kaufman RJ & Hegde RS (2007) The role of p58IPK in protecting the stressed endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Biol Cell 18, 3681–3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li B, Li D, Li GG, Wang HW & Yu AX (2008) P58 (IPK) inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress in human retinal capillary endothelial cells in vitro. Mol Vis 14, 1122–1128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung AS & Ferrara N (2011) Developmental and pathological angiogenesis. Ann Rev Cell Develop Biol 27, 563–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrara N (2009) VEGF-A: a critical regulator of blood vessel growth. Europ Cytokine Net 20, 158–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrara N, Carver-Moore K, Chen H, Dowd M, Lu L, O’Shea KS, Powell-Braxton L, Hillan KJ & Moore MW (1996) Heterozygous embryonic lethality induced by targeted inactivation of the VEGF gene. Nature 380, 439–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Penn JS, Madan A, Caldwell RB, Bartoli M, Caldwell RW & Hartnett ME (2008) Vascular endothelial growth factor in eye disease. Prog Retin Eye Res 27, 331–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hattori T, Shimada H, Nakashizuka H, Mizutani Y, Mori R & Yuzawa M (2010) Dose of intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) used as preoperative adjunct therapy for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Retina 30, 761–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kant S, Seth G & Anthony K (2009) Vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) in vitreous fluid of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Ann Ophthalmol 41, 170–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghosh R, Lipson KL, Sargent KE, Mercurio AM, Hunt JS, Ron D & Urano F (2010) Transcriptional regulation of VEGF-A by the unfolded protein response pathway. PLoS ONE 5, e9575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abcouwer SF, Marjon PL, Loper RK & Vander Jagt DL (2002) Response of VEGF expression to amino acid deprivation and inducers of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 43, 2791–2798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li J, Wang JJ, Yu Q, Wang M & Zhang SX (2009) Endoplasmic reticulum stress is implicated in retinal inflammation and diabetic retinopathy. FEBS Lett 583, 1521–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Y, Wang JJ, Li J, Hosoya KI, Ratan R, Townes T & Zhang SX (2012) Activating transcription factor 4 mediates hyperglycaemia-induced endothelial inflammation and retinal vascular leakage through activation of STAT3 in a mouse model of type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 55, 2533–2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhong Y, Wang JJ & Zhang SX (2012) Intermittent but not constant high glucose induces ER stress and inflammation in human retinal pericytes. Adv Exp Med Biol 723, 285–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fu D, Wu M, Zhang J, Du M, Yang S, Hammad SM, Wilson K, Chen J & Lyons TJ (2012) Mechanisms of modified LDL-induced pericyte loss and retinal injury in diabetic retinopathy. Diabetologia 55, 3128–3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oshitari T, Yoshida-Hata N & Yamamoto S (2011) Effect of neurotrophin-4 on endoplasmic reticulum stress-related neuronal apoptosis in diabetic and high glucose exposed rat retinas. Neurosci Lett 501,102–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang L, Zhang Y, Jiang Y, Willard L, Ortiz E, Wark L, Medeiros D & Lin D (2011) Dietary wolfberry ameliorates retinal structure abnormalities in db/db mice at the early stage of diabetes. Exp Biol Med 236, 1051–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan S, Zheng C, Chen ZQ, Liu R, Li GG, Hu WK, Pei H & Li B (2012) Expression of endoplasmic reticulum stress-related factors in the retinas of diabetic rats. Exp Diabet Res 2012, 743780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhong Y, Li J, Chen Y, Wang JJ, Ratan R & Zhang SX (2012) Activation of endoplasmic reticulum stress by hyperglycemia is essential for Muller cell-derived inflammatory cytokine production in diabetes. Diabetes 61, 492–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hu WK, Liu R, Pei H & Li B (2012) Endoplasmic reticulum stress-related factors protect against diabetic retinopathy. Exp Diabet Res 2012, 507986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jing G, Wang JJ & Zhang SX (2012) ER stress and apoptosis: a new mechanism for retinal cell death. Exp Diabet Res 2012, 589589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma JH, Wang JJ & Zhang SX (2014) The unfolded protein response and diabetic retinopathy. J Diabetes Res 2014, 160140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quigley HA (1996) Number of people with glaucoma worldwide. Br J Ophthalmol 80, 389–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quigley HA & Broman AT (2006) The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol 90, 262–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kwon YH, Fingert JH, Kuehn MH & Alward WL (2009) Primary open-angle glaucoma. N Engl J Med 360, 1113–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zode GS, Kuehn MH, Nishimura DY, Searby CC, Mohan K, Grozdanic SD, Bugge K, Anderson MG, Clark AF, Stone EM et al. (2011) Reduction of ER stress via a chemical chaperone prevents disease phenotypes in a mouse model of primary open angle glaucoma. J Clin Invest 121, 3542–3553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zode GS, Sharma AB, Lin X, Searby CC, Bugge K, Kim GH, Clark AF & Sheffield VC (2014) Ocular-specific ER stress reduction rescues glaucoma in murine glucocorticoid-induced glaucoma. J Clin Invest 124, 1956–1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peters JC, Bhattacharya S, Clark AF & Zode GS (2015) Increased endoplasmic reticulum stress in human glaucomatous trabecular meshwork cells and tissues. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 56, 3860–3868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fingert JH, Stone EM, Sheffield VC & Alward WL (2002) Myocilin glaucoma. Surv Ophthalmol 47, 547–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Libby RT, Gould DB, Anderson MG & John SW (2005) Complex genetics of glaucoma susceptibility. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 6, 15–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stone EM, Fingert JH, Alward WL, Nguyen TD, Polansky JR, Sunden SL, Nishimura D, Clark AF, Nystuen A, Nichols BE et al. (1997) Identification of a gene that causes primary open angle glaucoma. Science 275, 668–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Swiderski RE, Ross JL, Fingert JH, Clark AF, Alward WL, Stone EM & Sheffield VC (2000) Localization of MYOC transcripts in human eye and optic nerve by in situ hybridization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 41, 3420–3428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boughman JA, Conneally PM & Nance WE (1980) Population genetic studies of retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet 32, 223–235. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bunker CH, Berson EL, Bromley WC, Hayes RP & Roderick TH (1984) Prevalence of retinitis pigmentosa in Maine. Am J Ophthalmol 97, 357–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grossman GH, Watson RF, Pauer GJ, Bollinger K & Hagstrom SA (2011) Immunocytochemical evidence of Tulp1-dependent outer segment protein transport pathways in photoreceptor cells. Exp Eye Res 93, 658–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hagstrom SA, Adamian M, Scimeca M, Pawlyk BS, Yue G & Li T (2001) A role for the Tubby-like protein 1 in rhodopsin transport. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 42, 1955–1962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hagstrom SA, Watson RF, Pauer GJ & Grossman GH (2012) Tulp1 is involved in specific photoreceptor protein transport pathways. Adv Exp Med Biol 723, 783–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.North MA, Naggert JK, Yan Y, Noben-Trauth K & Nishina PM (1997) Molecular characterization of TUB, TULP1, and TULP2, members of the novel tubby gene family and their possible relation to ocular diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94, 3128–3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Iqbal M, Naeem MA, Riazuddin SA, Ali S, Farooq T, Qazi ZA, Khan SN, Husnain T, Riazuddin S, Sieving PA et al. (2011) Association of pathogenic mutations in TULP1 with retinitis pigmentosa in consanguineous Pakistani families. Arch Ophthalmol 129, 1351–1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ullah I, Kabir F, Iqbal M, Gottsch CB, Naeem MA, Assir MZ, Khan SN, Akram J, Riazuddin S, Ayyagari R et al. (2016) Pathogenic mutations in TULP1 responsible for retinitis pigmentosa identified in consanguineous familial cases. Mol Vis 22, 797–815. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lobo GP, Au A, Kiser PD & Hagstrom SA (2016) Involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress in TULP1 induced retinal degeneration. PLoS ONE 11, e0151806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chiang WC, Kroeger H, Sakami S, Messah C, Yasumura D, Matthes MT, Coppinger JA, Palczewski K, LaVail MM & Lin JH (2015) Robust endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of rhodopsin precedes retinal degeneration. Mol Neurobiol 52, 679–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alavi MV, Chiang WC, Kroeger H, Yasumura D, Matthes MT, Iwawaki T, LaVail MM, Gould DB & Lin JH (2015) In vivo visualization of endoplasmic reticulum stress in the retina using the ERAI reporter mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 56, 6961–6970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kroeger H, Messah C, Ahern K, Gee J, Joseph V, Matthes MT, Yasumura D, Gorbatyuk MS, Chiang WC, Lavail MM et al. (2012) Induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress genes, BiP and Chop, in genetic and environmental models of retinal degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53, 7590–7599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kunte MM, Choudhury S, Manheim JF, Shinde VM, Miura M, Chiodo VA, Hauswirth WW, Gorbatyuk OS & Gorbatyuk MS (2012) ER stress is involved in T17M rhodopsin-induced retinal degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53, 3792–3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shinde VM, Sizova OS, Lin JH, Lavail MM & Gorbatyuk MS (2012) ER stress in retinal degeneration in S334ter rho rats. PLoS ONE 7, e33266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shimazawa M, Inokuchi Y, Ito Y, Murata H, Aihara M, Miura M, Araie M & Hara H (2007) Involvement of ER stress in retinal cell death. Mol Vis 13, 578–587. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chan P, Stolz J, Kohl S, Chiang WC & Lin JH (2016) Endoplasmic reticulum stress in human photoreceptor diseases. Brain Res 1648, 538–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gorbatyuk MS, Knox T, LaVail MM, Gorbatyuk OS, Noorwez SM, Hauswirth WW, Lin JH, Muzyczka N & Lewin AS (2010) Restoration of visual function in P23H rhodopsin transgenic rats by gene delivery of BiP/Grp78. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107, 5961–5966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bhootada Y, Kotla P, Zolotukhin S, Gorbatyuk O, Bebok Z, Athar M & Gorbatyuk M (2016) Limited ATF4 expression in degenerating retinas with ongoing ER stress promotes photoreceptor survival in a mouse model of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. PLoS ONE 11, e0154779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nashine S, Bhootada Y, Lewin AS & Gorbatyuk M (2013) Ablation of C/EBP homologous protein does not protect T17M RHO mice from retinal degeneration. PLoS ONE 8, e63205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Adekeye A, Haeri M, Solessio E & Knox BE (2014) Ablation of the proapoptotic genes chop or Ask1 does not prevent or delay loss of visual function in a P23H transgenic mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa. PLoS ONE 9, e83871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chiang WC, Joseph V, Yasumura D, Matthes MT, Lewin AS, Gorbatyuk MS, Ahern K, LaVail MM & Lin JH (2016) Ablation of Chop transiently enhances photoreceptor survival but does not prevent retinal degeneration in transgenic mice expressing human P23H rhodopsin. Adv Exp Med Biol 854, 185–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kohl S, Zobor D, Chiang W-C, Weisschuh N, Staller J, Menendez IG, Chang S, Beck SC, Garrido MG, Sothilingam V et al. (2015) Mutations in the unfolded protein response regulator ATF6 cause the cone dysfunction disorder achromatopsia. Nat Genet 47, 757–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chiang WC, Chan P, Wissinger B, Vincent A, Skorczyk-Werner A, Krawczynski MR, Kaufman RJ, Tsang SH, Heon E, Kohl S et al. (2017) Achromatopsia mutations target sequential steps of ATF6 activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114, 400–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Skorczyk-Werner A, Chiang WC, Wawrocka A, Wicher K, Jarmuz-Szymczak M, Kostrzewska-Poczekaj M, Jamsheer A, Ploski R, Rydzanicz M, Pojda-Wilczek D et al. (2017) Autosomal recessive cone-rod dystrophy can be caused by mutations in the ATF6 gene. Eur J Hum Genet 25, 1210–1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wu J, Rutkowski DT, Dubois M, Swathirajan J, Saunders T, Wang J, Song B, Yau GD & Kaufman RJ (2007) ATF6αlpha optimizes long-term endoplasmic reticulum function to protect cells from chronic stress. Dev Cell 13, 351–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yamamoto K, Sato T, Matsui T, Sato M, Okada T, Yoshida H, Harada A & Mori K (2007) Transcriptional induction of mammalian ER quality control proteins is mediated by single or combined action of ATF6αlpha and XBP1. Dev Cell 13, 365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Baker DJ, Childs BG, Durik M, Wijers ME, Sieben CJ, Zhong J, Saltness RA, Jeganathan KB, Verzosa GC, Pezeshki A et al. (2016) Naturally occurring p16 (Ink4a)-positive cells shorten healthy lifespan. Nature 530, 184–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Baker DJ, Wijshake T, Tchkonia T, LeBrasseur NK, Childs BG, van de Sluis B, Kirkland JL & van Deursen JM (2011) Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature 479, 232–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Childs BG, Durik M, Baker DJ & van Deursen JM (2015) Cellular senescence in aging and age-related disease: from mechanisms to therapy. Nat Med 21, 1424–1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Demaria M, Ohtani N, Youssef SA, Rodier F, Toussaint W, Mitchell JR, Laberge RM, Vijg J, Van Steeg H, Dolle ME et al. (2014) An essential role for senescent cells in optimal wound healing through secretion of PDGF-AA. Dev Cell 31, 722–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Munoz-Espin D, Canamero M, Maraver A, Gomez-Lopez G, Contreras J, Murillo-Cuesta S, Rodriguez-Baeza A, Varela-Nieto I, Ruberte J, Collado M et al. (2013) Programmed cell senescence during mammalian embryonic development. Cell 155, 1104–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Munoz-Espin D & Serrano M (2014) Cellular senescence: from physiology to pathology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 15, 482–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Storer M, Mas A, Robert-Moreno A, Pecoraro M, Ortells MC, Di Giacomo V, Yosef R, Pilpel N, Krizhanovsky V, Sharpe J et al. (2013) Senescence is a developmental mechanism that contributes to embryonic growth and patterning. Cell 155, 1119–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sapieha P, Hamel D, Shao Z, Rivera JC, Zaniolo K, Joyal JS & Chemtob S (2010) Proliferative retinopathies: angiogenesis that blinds. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 42, 5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Oubaha M, Miloudi K, Dejda A, Guber V, Mawambo G, Germain MA, Bourdel G, Popovic N, Rezende FA, Kaufman RJ et al. (2016) Senescence-associated secretory phenotype contributes to pathological angiogenesis in retinopathy. Sci Transl Med 8,362ra144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Campisi J & d’Adda di Fagagna F (2007) Cellular senescence: when bad things happen to good cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8, 729–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Moiseeva O, Deschenes-Simard X, Pollak M & Ferbeyre G (2013) Metformin, aging and cancer. Aging 5, 330–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Binet F, Mawambo G, Sitaras N, Tetreault N, Lapalme E, Favret S, Cerani A, Leboeuf D, Tremblay S, Rezende F et al. (2013) Neuronal ER stress impedes myeloid-cell-induced vascular regeneration through IRE1alpha degradation of netrin-1. Cell Metab 17, 353–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Levin LA (1997) Mechanisms of optic neuropathy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 8, 9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Berkelaar M, Clarke DB, Wang YC, Bray GM & Aguayo AJ (1994) Axotomy results in delayed death and apoptosis of retinal ganglion cells in adult rats. J Neurosci 14, 4368–4374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.McKernan DP & Cotter TG (2007) A critical role for Bim in retinal ganglion cell death. J Neurochem 102, 922–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Selles-Navarro I, Ellezam B, Fajardo R, Latour M & McKerracher L (2001) Retinal ganglion cell and nonneuronal cell responses to a microcrush lesion of adult rat optic nerve. Exp Neurol 167, 282–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Howell GR, Libby RT, Jakobs TC, Smith RS, Phalan FC, Barter JW, Barbay JM, Marchant JK, Mahesh N, Porciatti V et al. (2007) Axons of retinal ganglion cells are insulted in the optic nerve early in DBA/2J glaucoma. J Cell Biol 179, 1523–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kerrigan LA, Zack DJ, Quigley HA, Smith SD & Pease ME (1997) TUNEL-positive ganglion cells in human primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 115, 1031–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Libby RT, Li Y, Savinova OV, Barter J, Smith RS, Nickells RW & John SW (2005) Susceptibility to neurodegeneration in a glaucoma is modified by Bax gene dosage. PLoS Genet 1, 17–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Quigley HA (1993) Open-angle glaucoma. N Engl J Med 328, 1097–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Quigley HA, Nickells RW, Kerrigan LA, Pease ME, Thibault DJ & Zack DJ (1995) Retinal ganglion cell death in experimental glaucoma and after axotomy occurs by apoptosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 36, 774–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Weinreb RN & Khaw PT (2004) Primary open-angle glaucoma. Lancet 363, 1711–1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Qu J, Wang D & Grosskreutz CL (2010) Mechanisms of retinal ganglion cell injury and defense in glaucoma. Exp Eye Res 91, 48–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hu Y, Park KK, Yang L, Wei X, Yang Q, Cho KS, Thielen P, Lee AH, Cartoni R, Glimcher LH et al. (2012) Differential effects of unfolded protein response pathways on axon injury-induced death of retinal ganglion cells. Neuron 73, 445–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Awai M, Koga T, Inomata Y, Oyadomari S, Gotoh T, Mori M & Tanihara H (2006) NMDA-induced retinal injury is mediated by an endoplasmic reticulum stress-related protein, CHOP/GADD153. J Neurochem 96, 43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Guo Q, Sopher BL, Furukawa K, Pham DG, Robinson N, Martin GM & Mattson MP (1997) Alzheimer’s presenilin mutation sensitizes neural cells to apoptosis induced by trophic factor withdrawal and amyloid beta-peptide: involvement of calcium and oxyradicals. J Neurosci 17, 4212–4222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hayashi T, Saito A, Okuno S, Ferrand-Drake M, Dodd RL & Chan PH (2005) Damage to the endoplasmic reticulum and activation of apoptotic machinery by oxidative stress in ischemic neurons. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 25, 41–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Imai Y & Takahashi R (2004) How do Parkin mutations result in neurodegeneration? Curr Opin Neurobiol 14, 384–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Larner SF, Hayes RL, McKinsey DM, Pike BR & Wang KK (2004) Increased expression and processing of caspase-12 after traumatic brain injury in rats. J Neurochem 88, 78–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tajiri S, Oyadomari S, Yano S, Morioka M, Gotoh T, Hamada JI, Ushio Y & Mori M (2004) Ischemia-induced neuronal cell death is mediated by the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway involving CHOP. Cell Death Differ 11, 403–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tobisawa S, Hozumi Y, Arawaka S, Koyama S, Wada M, Nagai M, Aoki M, Itoyama Y, Goto K & Kato T (2003) Mutant SOD1 linked to familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, but not wild-type SOD1, induces ER stress in COS7 cells and transgenic mice. Biochem Biophys Res Comm 303, 496–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wootz H, Hansson I, Korhonen L, Napankangas U & Lindholm D (2004) Caspase-12 cleavage and increased oxidative stress during motoneuron degeneration in transgenic mouse model of ALS. Biochem Biophys Res Comm 322, 281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kroeger H, Grimsey N, Paxman R, Chiang WC, Plate L, Jones Y, Shaw PX, Trejo J, Tsang SH, Powers E et al. (2018) The unfolded protein response regulator ATF6 promotes mesodermal differentiation. Sci Signal 11, pii: eaan5785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]