Abstract

A series of vasopressin receptor V1a ligands have been synthesized for positron emission tomography (PET) imaging. The lead compound (1S,5R)-1 ((4-(1Hindol-3-yl)-3-methoxyphenyl)((1S,5R)-1,3,3-trimethyl-6-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone) and its F-ethyl analog 6c exhibited the best combination of high binding affinity and optimal lipophilicity within the series. (1S,5R)-1 was radiolabeled with 11C for PET studies. [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 readily entered the mouse (4.7% ID/g tissue) and prairie vole brains (~2% ID/g tissue) and specifically (30–34%) labeled V1a receptor. The common animal anesthetic Propofol significantly blocked the brain uptake of [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 in the mouse brain, whereas anesthetics Ketamine and Saffan increased the uptake variability. Future PET imaging studies with V1a radiotracers in non-human primates should be performed in awake animals or using anesthetics that do not affect the V1a receptor.

Keywords: Vasopressin receptor, positron emission tomography, radiotracers

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION:

Arginine vasopressin (AVP) is essential for a wide range of physiological functions in the periphery and central nervous system (CNS). In the periphery, AVP works as a hormone that regulates water reabsorption, blood pressure, cardiovascular homeostasis, hormone secretion [1, 2]. In the CNS, AVP acts as a neuromodulator that activates various brain regions through binding to vasopressin receptors involved in the regulation of social, emotional and cognitive behaviors [3]. Social attunement is fundamental to sexual behavior, pair-bonding, maternal behavior, mate guarding, social memory and biparental care [4, 5]. The role of AVP in human social behavior [6–9] is an emerging area of research in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [10, 11].

The action of AVP is mediated by three known G-protein-coupled receptor subtypes: V1a, V1b, and V2 (see for review) [6]. The receptors V1a and V1b are expressed in the CNS, but there is no clear evidence of the expression of V2 in the brain of mammals [6, 12–15]. Many social behavioral effects of AVP are primarily mediated by V1a receptor [6–9, 16–19]. This is pertinent to ASD where blockade of the V1a receptor may improve social communication in adults with high-functioning ASD [20].

In vivo imaging and quantification of V1a receptors in human brain could provide an important advance in the understanding of ASD and other neuropsychiatric disorders related to this vasopressin receptor subtype and potentially facilitate the development of novel V1a drugs.

Such studies may be conducted using positron emission tomography (PET). PET is an advanced technique to quantify neuronal receptors and their occupancy in vivo. The development of a PET radiotracer for V1a imaging is of considerable importance, however, the development of a PET radioligand suitable for quantification of the V1a receptor in healthy and diseased brains remains challenging.

A previous study [21] described the first V1a PET radiotracers, but imaging studies in animals with these radiotracers have not been reported, possibly because of the suboptimal molecular weights (700–800 Dalton) of the radiotracers for sufficient blood-brain barrier permeability.

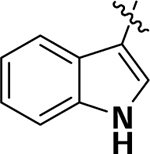

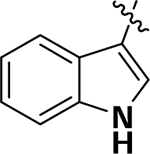

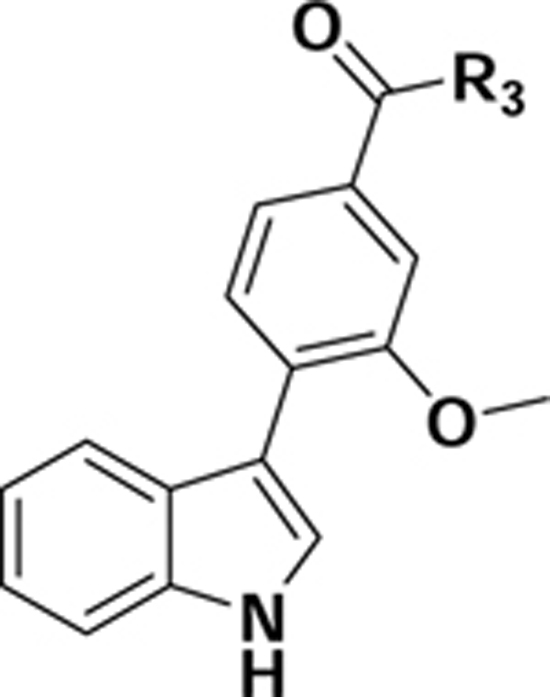

We aimed to develop a small molecule PET radiotracer based on the scaffold of compound (1S,5R)-1 (Fig. 1), a high affinity and selective V1a antagonist (KiV1a = 0.1 nM; KiV2 = 600 nM) developed by Pfizer [22]. In this report, we describe the design, synthesis, radiolabeling and in vitro and in vivo characterization in mice of a series of high V1a binding affinity derivatives of 1 as potential probes for PET imaging of V1a receptors.

Figure 1.

Structure of high binding affinity and selective V1a receptor antagonist (1S,5R)-1.

2. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

2.1. Chemistry:

A series of V1a ligands was synthesized as shown in Schemes 1–4. The synthesis of key intermediates, racemic 4-iodo-phenyl-(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone derivatives 3 including the previously published 3a, [22] is summarized in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of key intermediates.

Reagents and conditions: a) EDC, HOBT, DIEA, DMF

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of compounds 13a-e.

Reagents and conditions: a) Pd(dppf)Cl2.DCM, Na2CO3, 1,4-Dioxane/H2O; b) TFA, MC; c) LiOH, THF/ H2O; d) EDC, HOBT, DIEA, DMF.

The first group of V1a ligands 1, 6a-b was synthesized in a high yield by the Suzuki reaction [20] of racemic iodo-arenes 3a-c and tert-butyl 3-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)-1H-indole-1carboxylate 4 followed by cleavage of the tert-Boc-group. The hydroxyl compound 6a reacted with 2fluoroethyl tosylate in the presence of Cs2CO3 in DMF to give the fluoroethyl compound 6c in high yield (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of compounds 1 and 6a-c.

Reagents and conditions: a) Pd(dppf)Cl2.DCM, Na2CO3, 1,4-Dioxane/H2O; b) TFA, MC; c) 2fluoroethyl Tosylate, Cs2CO3, DMF.

Racemic 1 was separated into two enantiomers (1S,5R)-1 and (1R,5S)-1 [22] by preparative chiral HPLC. Compound 6a was also separated in two enantiomers (1S,5R)-6a and (1R,5S)-6a using chiral supercritical fluid chromatography.

Synthesis of compounds 8a-l was achieved by the Suzuki reaction of the iodo-intermediates 3a, 3c-d with commercially available boronic acids or in-house prepared boronic esters 7 (Scheme 3) [21].

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of vasopressin ligands 8a-l.

Reagents and conditions: a) Pd(dppf)Cl2.DCM, Na2CO3, 1,4-Dioxane/H2O.

Compounds 13a-e were prepared in four steps as shown in Scheme 4. The Suzuki cross-coupling reaction between methyl 4-bromo-3-methoxybenzoate 9 and tertbutyl 3-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan2-yl)-1H-indole-1-carboxylate 4 led to the formation of the benzoic ester derivative 10 in an excellent yield. The ester derivative 10 underwent tert-Boc deprotection followed by saponification with aqueous LiOH to yield the carboxylic acid derivative 12. Coupling of 12 with various amines led to the desired amide derivatives 13a-e.

2.2. Structure–Activity Relationship:

The purpose of the study was to develop a V1a ligand with high V1a receptor binding affinity and suitable molecular properties for brain PET (molecular weight MW < 500 Dalton, lipophilicity logD < 5). In addition, the suitable ligand structures have to possess a fluorine atom or methyl group for 18F- or 11C-radiolabeling.

The high binding affinity requirement is a crucial component in the PET radiotracer development and is based on the conventional equation , where Bmax is receptor density in the brain tissue and KD is the dissociation constant [23]. In many reports, the V1a receptor density in the brain tissue of various species was determined semi-quantitatively [15, 24]. The quantitatively determined V1a density value (Bmax) in the mammalian brain varies substantially among different reports, perhaps due to the high nonspecific binding and insufficient selectivity of the available in vitro radiotracers that were used in the assays: in rat – 4 fmol/mg protein [25], 10–15 fmol/mg protein [26], 20–80 fmol/mg protein [13], 150–408 fmol/mg protein [27]; in golden hamster −12 fmol/mg protein [28]. The required binding affinity for a good V1a PET radiotracer should be in the range of Ki < 0.4 – 40 nM, but the deficiency of the in vitro binding assay makes this estimate rather imprecise. Based on the above approximation of the required binding affinity and other structural properties, the V1a ligand (1S,5R)-1 (Ki = 0.1 nM, MW = 402, logD = 4.7) was selected as a lead for this project. The binding affinity of the lead was confirmed in this study (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Binding inhibition and lipophilicities of V1a ligands 1, 6b-c, 8a-l.

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | R | R1 | R2 | logD7,4 | % Binding inhibition a (concentration) | |

| (10−9M) | (10−8M) | |||||

| (1S,5R)-1 |  |

OCH3 | H | 4.7 | 51.4 | 87.9b |

| (1R,5S)-1 |  |

OCH3 | H | 4.7 | 7.1 | 8.9b |

| 6b |  |

H | H | 4.8 | 33.4 | 77.1 |

| 6c |  |

OCH2CH2F | H | 4.9 | 45.1 | 92.6 |

| 8a |  |

OCH3 | H | 3.9 | 2.9 | 33.9 |

| 8b |  |

OCH3 | H | 4.0 | 9.7 | 16 |

| 8c |  |

OCH3 | H | 6.0 | 1.8 | 18.7 |

| 8d |  |

OCH3 | H | 2.9 | 4.4 | 28.7 |

| 8e |  |

OCH3 | H | 3.5 | −4.7 | 44.2 |

| 8f |  |

OCH3 | H | 2.8 | 5.2 | 39.5 |

| 8g |  |

H | H | 5.0 | 23.7c | 84.3 |

| 8h |  |

H | H | 4.4 | 10.5 | 28.9 |

| 8i |  |

H | H | 4.4 | 12.8 | 43.9 |

| 8j |  |

H | H | 4.4 | −6.6 | 18.2 |

| 8k |  |

H | F | 5.8 | 22.8 | 81.2 |

| 8l |  |

H | F | 4.5 | 2.4 | 19.8 |

Values are the means of two experiments, each in duplicate.

The V1a inhibition binding affinity constant values of (1S,5R)-1 (Ki = 0.66 nM) and (1R,5S)-1 (Ki > 10 nM) were determined in a separate binding assay. This result is in agreement with previously published data for (1S,5R)-1 (Ki = 0.1 nM) [22].

Compound 8g was described previously (Ki = 0.05 nM) [22].

The overall objective of this research was to synthesize a series of analogs of 1 with appropriate characteristics for brain PET radiotracer including high binding affinity Ki < 0.4 – 40 nM) (see previous paragraph for the rational). The other necessary properties for cerebral PET tracer include optimal lipophilicity (logD < 5) and molecular weight MW < 500 Dalton [29, 30].

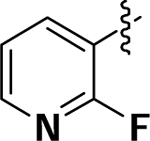

The fluoro derivatives 6b, 8a, and 8b exhibited satisfactory lipophilicity, but lower binding affinity compared to the lead 1 (Table 1).

The fluoroethyl-analog 6c manifested high binding affinity and lipophilicity that was comparable to the lead 1. The derivative 8c, synthesized by N-methylation of 1, resulted to an increase of lipophilicity and decrease in binding affinity.

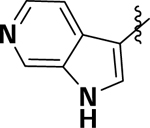

Azaindole derivatives 8d-8f exhibited an optimal lipophilicity, but the binding affinities were lower than that of 1.

Interestingly, tolyl derivatives 8g and 8k, those are less bulky than 1, exhibited good binding affinity, whereas the picolyl derivatives (8h-j and 8l) showed poor V1a binding affinity (Table 1).

Replacement of the 1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl moiety in compounds 13a-e with other cyclic amines substituents resulted in a loss of the V1a binding affinity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Binding Affinities of the Derivatives 13a-e.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | R | logD7,4 | % Binding inhibition a (concentration) | |

| (10−9M) | (10−8M) | |||

| 13a |  |

0.7 | 15.7 | 4.7 |

| 13b |  |

1.6 | 13.7 | 9.0 |

| 13c |  |

0.2 | 5.7 | 6.2 |

| 13d |  |

5.8 | 7.4 | 4.8 |

| 13e |  |

3.2 | 5.0 | 4.6 |

Values are the means of % inhibitions of two independent experiments, each in duplicate.

2.3. Radiochemistry:

Two compounds of the series, the lead (1S,5R)-1 and its F-ethyl analog 6c, exhibited the best combination of high binding affinity and optimal lipophilicity (Table 1) and were suitable for PET radiolabeling with 11C and 18F, respectively. Because of relative simplicity of 11Cradiolabeling we have chosen to radiolabel (1S,5R)-1 with 11C for further animal experiments. Radiolabelled [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 was prepared by 11C-methylation of the corresponding phenol precursor (1S,5R)-6a (Scheme 5). The precursor (1S,5R)-6a (ee −99.5%) was obtained by supercritical fluid chiral chromatographic separation of racemic 6a. [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 was prepared with a radiochemical yield of 10–15%, specific radioactivity 8000 – 16000 mCi/µmol (296 – 590 GBq/µmol) and radiochemical purity > 95%. The enantiomeric purity (e.e.>95%) of [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 was demonstrated by chiral HPLC analysis.

Scheme 5.

Radiosynthesis of [11CH3](1S,5R)-1

Radiotracer [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 undergoes a rapid radiolysis in saline solution, but it is stable for at least 1 h in saline solution containing 7–8% alcohol.

2.4. Biodistribution studies in rodents.

Radioligand [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 was evaluated in rodents as a potential PET radiotracer for imaging V1a receptors.

2.4.1. Baseline studies in CD-1 mice.

After intravenous injection [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 manifested high initial brain uptake with peak concentration of radioactivity at 5 min post-injection (4.7 %ID/g tissue) followed by washout. The lateral septum was the region with the highest accumulation of radioactivity, which is consistent with previous in vitro semi-quantitative autoradiography results in C57B6 mice [31]. The uptake in the hippocampus, cortex, and the rest of brain was lower than that in the septum (Table 3).

Table 3.

Regional distribution of [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 in CD1 male mouse brain (mean %ID/g tissue ± SD, n=3)

| 5 min | 15 min | 30 min | 60 min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Septum | 4.71±0.57 | 2.70±0.06 | 1.94±0.76 | 0.86±0.18 |

| Hippocampus | 3.37±0.32 | 2.17±0.06 | 1.62±0.52 | 0.75±0.18 |

| Cortex | 4.44±0.52 | 2.41±0.08 | 1.52±0.52 | 0.60±0.08 |

| Rest of brain | 3.95±0.35 | 2.34±0.02 | 1.54±0.52 | 0.65±0.12 |

2.4.2. Dose-Escalation Blocking in CD-1 Mice.

In all studied brain regions (septum, hippocampus, cortex) at 60 min after injection of [11CH3](1S,5R)-1, radiotracer binding was blocked by injection of V1a ligand 8g (Ki = 0.05 nM) [22] in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 2). At the highest blocker dose of 3 mg/kg, the reduction of radioactivity uptake in the septum, cortex, and rest of brain was 30%, 26%, and 14%, respectively. The blockade in the septum was significant, suggesting that [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 specifically labels V1a receptors in this brain region.

Figure 2.

Dose-dependent blocking of [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 (0.1 mCi) uptake with the V1a ligand 8g (subcutaneous blocker) in the CD-1 mouse brain at 30 min after radiotracer injection. Abbreviations: SEP, lateral septum; Ctx, cortex. The blocking study demonstrates that [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 specifically (30%) labels V1a in the septum. Data: mean %ID/g tissue x body weight ± SD (n = 3). *P = 0.004, significantly different from baseline (ANOVA).

2.4.3. Brain regional biodistribution studies in male prairie voles.

Previous studies revealed an involvement of V1a receptor in mediation of paternal behavior, selective aggression and affiliation in monogamous rodent species including prairie voles [12], Taiwan voles [32] and deer mice [33]. We examined the regional distribution of [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 in male prairie voles. The uptake of [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 was higher in the superior colliculus and thalamus and lower in the cortex and rest of brain (Fig. 3). This distribution of the radiotracer is in agreement with the in vitro distribution of V1a in the prairie voles [12]. The uptake of the radiotracer [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 was reduced in the blocking studies with 1. The blocking was significant only in the superior colliculus (Fig. 3), the region with the greatest density of V1a [12].

Figure 3.

Brain regional distribution of [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 (0.1 mCi) in the baseline and blocking studies in the prairie vole brain at 30 min after radiotracer injection. Blocker is racemic 1 (2 mg/kg). Abbreviations: Ctx, cortex; Th, thalamus; S.Coll, superior colliculus; Rest, the rest of brain. The blocking study demonstrates that [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 specifically (34%) labels V1a in the superior colliculus. Data: mean %ID/g tissue ± SD (n = 6). *P = 0.01, significantly different from baseline (ANOVA).

2.4.4. Effect of anesthetics.

Previous research established that common animal anesthetics such as Propofol [34] and NMDA antagonists [35] interact with the vasopressin receptor system and alter the binding of V1a receptors. Because in our lab we commonly use Propofol and an NMDA antagonist Ketamine as anesthetics for baboon PET imaging, we investigated an effect of these anesthetics and another common animal anesthetic Saffan on the brain regional biodistribution of [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 in mice.

The study demonstrated that intraperitoneal treatment of CD-1 mice with all three anesthetics greatly increased the variability of the radiotracer brain uptake as compared with controls (28–43% (anesthetics); 0.4–3.5% (controls)) (Fig. 4). The study showed a significant reduction of the radiotracer uptake in the hippocampus in the mice treated with Propofol and insignificant reduction in other brain regions. Ketamine and Saffan treatment did not significantly change the radiotracer brain uptake. However, in the case of Saffan, there was a trend toward a decrease in the uptake. Saffan is composed of two neuroactive steroids alfaxalone and alfadolone (3:1). Neuroactive steroids are known to modulate the secretion of vasopressin [36] and, thus, may affect the V1a receptor radiotracer binding.

Figure 4.

Effect of three anesthetics (Propofol, Ketamine and Saffan) on the brain uptake of [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 in CD-1 mice at 30 min after the radiotracer injection. The anesthetics were injected ip (80 mg/kg), 30 min prior the radiotracer. Data: mean %ID/g tissue ± SD (n = 3). Abbreviations: Hipp, hippocampus; Ctx, cortex; SEP, septum; Rest, the rest of brain. All three anesthetics increased the variability of the radiotracer uptake. The radiotracer uptake was significantly lower in the hippocampus in mice treated with Propofol. *P < 0.01, significantly different from control (ANOVA).

The results of this study and previous research [34] suggest that Propofol blocks the V1a and may be unsuitable as an anesthetic for future vasopressin receptor PET imaging in non-human primates. The high variability of the radiotracer uptake in the Saffan and ketamine experiments demonstrated that these two anesthetics are not benign for V1a receptor imaging and different classes of anesthetics should be considered.

3. CONCLUSIONS

A novel series of V1a receptor ligands has been developed for PET imaging. The lead ligand (1S,5R)-1 with the best binding affinity (0.66 nM) was radiolabeled with 11C for positron emission tomography studies. [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 readily entered the mouse (4.7% ID/g tissue) and prairie vole brains (~2% ID/g tissue) and specifically (30 – 34%) labeled V1a receptors. The common animal anesthetic Propofol significantly blocks the brain uptake of [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 in the mouse brain, whereas anesthetics Ketamine and Saffan increase the variability of uptake. Future PET imaging studies with [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 or other V1a radiotracers in non-human primates should be performed in awake animals or use anesthetics that do not affect the V1a receptor. Such studies are needed to advance our understanding of the role of V1a receptor in social behavior.

4. EXPERIMENTAL SECTION:

All reagents were used directly as obtained commercially unless otherwise noted. Reaction progress was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using silica gel 60 F254 (0.040–0.063 mm) with detection by UV. All moisture-sensitive reactions were performed under an argon atmosphere using ovendried glassware and anhydrous solvents. Column flash chromatography was carried out using BDH silica gel 60Å (40–63 micron). Analytical TLC was performed on plastic sheets coated with silica gel 60 F254 (0.25 mm thickness, E. Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). 1H NMR spectra were recorded with a Bruker-500 NMR spectrometer at nominal resonance frequencies of 500 MHz in CDCl3, CD3OD or DMSO-d6 (referenced to internal Me4Si at δ 0 ppm). The chemical shifts (δ) were expressed in parts per million (ppm). High-resolution mass spectra were recorded utilizing electrospray ionization (ESI) at the University of Notre Dame Mass Spectrometry facility. All compounds that were tested in the biological assays were analyzed by combustion analysis (CHN) to confirm a purity of >95%. A dose calibrator (Capintec 15R) was used for all radioactivity measurements. Radiolabelling was performed with a modified GE MicroLab radiochemistry box. The experimental animal protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

4.1. Chemistry

(4-Iodo-3-methoxyphenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone (3a):

To the mixture of 4-iodo-3-methoxybenzoic acid (1a) (1.0 g, 3.60 mmol), 1,3,3-trimethyl-6-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octane (0.55 g, 3.60 mmol), EDC.HCl (0.83 g, 4.32 mmol), and HOBT (0.58 g, 4.32 mmol), in DMF (10 mL) was added N,N-Diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) (1.25 mL, 7.20 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight and then partitioned between EtOAc and brine. The organic layer was separated, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under a vacuum. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (Hexane:EtOAc = 3:7) to give (4-iodo-3-methoxyphenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone as a white solid (1.12 g, 75.4% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.57 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 4.00 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 3.93 (s, 3H), 3.60 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 3.30 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 2.27–2.24 (m, 1H), 1.81–1.77 (m, 1H), 1.62–1.60 (m, 1H), 1.50–1.47 (m, 1H), 1.38–1.34 (m, 2H), 1.25 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.16 (s, 3H), 1.06 (s, 3H), 0.98 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H).

(3-Hydroxy-4-iodophenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone (3b):

To the mixture of 3-hydroxy-4-iodobenzoic acid (1b) (1.0 g, 3.78 mmol), 1,3,3-trimethyl-6-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octane (0.58 g, 3.78 mmol), EDC.HCl (0.87 g, 4.53 mmol), and HOBT (0.61 g, 4.53 mmol), in DMF (10 mL) was added DIEA (1.31 mL, 7.56 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight and then partitioned between EtOAc and brine. The organic layer was separated, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under a vacuum. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (Hexane:EtOAc = 3:7) to give (3hydroxy-4iodophenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone as a white solid (1.20 g, 80.6% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.78 (s, 1H), 7.66 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.08–7.04 (m, 1H), 6.69– 6.65 (m, 1H), 4.59 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 3.60 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 3.26–3.23 (m, 1H), 1.76–1.74 (m, 1H), 1.57 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.48–1.41 (m, 2H), 1.38–1.30 (m, 2H), 1.19 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.08 (s, 3H), 1.00 (s, 3H), 0.93 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H).

(2-Fluoro-4-iodophenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone (3c):

To the mixture of 2-fluoro-4-iodobenzoic acid (1c) (1.0 g, 3.75 mmol), 1,3,3-trimethyl-6-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octane (0.58 g, 3.75 mmol), EDC.HCl (0.86 g, 4.50 mmol), and HOBT (0.61 g, 4.50 mmol), in DMF (10 mL) was added DIEA (1.31 mL, 7.50 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight and then partitioned between EtOAc and brine. The organic layer was separated, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under a vacuum. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (Hexane:EtOAc = 4:6) to give (2fluoro-4iodophenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone as a white solid (1.25 g, 82.9% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.36–7.33 (m, 1H), 7.32–7.28 (m, 1H), 7.24–7.20 (m, 1H), 4.65 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 3.64 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 3.26 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 3.23– 3.08 (m, 1H), 1.82–1.79 (m, 1H), 1.48–1.47 (m, 1H), 1.44–1.41 (m, 2H), 1.38–1.32 (m, 2H), 1.17 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.10 (s, 3H), 1.04 (s, 3H), 0.94 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H).

(4-Iodophenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone (3d):

To the mixture of 4iodobenzoic acid (1d) (1.0 g, 4.03 mmol), 1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octane (0.62 g, 4.03 mmol), EDC.HCl (0.92 g, 4.83 mmol), and HOBT (0.65 g, 4.83 mmol), in DMF (10 mL) was added DIEA (1.50 mL, 8.60 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight and then partitioned between EtOAc and brine. The organic layer was separated, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under a vacuum. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (Hexane:EtOAc = 4:6) to give (4-iodophenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan6-yl)methanone as a white solid (1.30 g, 84.4% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.56 (t, J = 10.0 Hz, 2H), 7.35 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 2H), 3.96 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 3.61 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.30 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 2.27–2.24 (m, 1H), 1.80–1.77 (m, 1H), 1.62–1.54 (m, 2H), 1.49–1.44 (m, 1H), 1.40–1.33 (m, 1H), 1.23 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.15 (s, 3H), 1.05 (s, 3H), 0.97 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H).

Tert-butyl 3-(2methoxy-4-(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octane-6-carbonyl)phenyl)-1Hindole-1-carboxylate (5a):

To a solution of (4iodo-3-methoxyphenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone (3a) (0.3 g, 0.72 mmol) and tertbutyl 3-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2dioxaborolan-2-yl)-1H-indole-1-carboxylate (4) (0.27 g, 0.80 mmol) in 1,4-dioxane (4.0 mL) was added 1.0 mL of water. The reaction mixture was degassed with argon for about 30 minutes. After that Pd(dppf)Cl2.DCM (0.03 g, 0.036 mmol) and Na2CO3 (0.15 g, 1.45 mmol) were added to the reaction mixture and again degassed with argon for another 20 minutes. The reaction mixture was stirred under reflux for 3 h. After cooled down to room temperature, the mixture was extracted with EtOAc, washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (Hexane/EtOAc = 3:7) to afford 5a as a brown solid (0.32 g, 87.9%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.22 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.82 (s, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.55–7.53 (m, 1H), 7.36 (s, 1H), 7.27 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.13 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 4.68 (s, 1H), 3.89 (s, 3H), 3.64 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.43–3.40 (m, 1H), 3.28 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 2.32–2.29 (m, 1H), 1.84–1.82 (m, 1H), 1.76–1.73 (m, 2H), 1.71 (s, 9H), 1.60 (s, 1H), 1.54–1.47 (m, 1H), 1.43–1.37 (m, 1H), 1.20 (s, 3H), 1.10 (s, 3H), 1.00 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H).

Tert-butyl 3-(2hydroxy-4-(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octane-6-carbonyl)phenyl)-1Hindole-1-carboxylate (5b):

To a solution of (3hydroxy-4-iodophenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone (3b) (0.5 g, 1.25 mmol) and tertbutyl 3-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2dioxaborolan-2-yl)-1H-indole-1-carboxylate (4) (0.47 g, 1.38 mmol) in 1,4-dioxane (10.0 mL) was added 2.0 mL of water. The reaction mixture was degassed with argon for about 30 minutes. After that Pd(dppf)Cl2.DCM (0.05 g, 0.063 mmol) and Na2CO3 (0.26 g, 2.50 mmol) were added to the reaction mixture and again degassed with argon for another 20 minutes The reaction mixture was stirred under reflux for 3 h. After cooled down to room temperature, the mixture was extracted with EtOAc, washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (Hexane/EtOAc =3:7) to afford 5b as a brown solid (0.48 g, 78.5%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.26 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.81(s, 1H), 7.59–7.56 (m, 1H), 7.46–7.40 (m, 2H), 7.30 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.11–7.06 (m, 1H), 4.68 (s, 1H), 3.64 (d, J = 10.0 Hz,

1H), 3.43–3.40 (m, 1H), 3.28 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 2.32–2.29 (m, 1H), 1.84–1.82 (m, 1H), 1.76–1.73 (m, 2H), 1.72 (s, 9H), 1.60 (s, 1H), 1.54–1.47 (m, 1H), 1.43–1.37 (m, 1H), 1.28 (s, 3H), 1.15 (s, 3H), 1.09 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H).

Tert-butyl 3-(3fluoro-4-(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octane-6-carbonyl)phenyl)-1H-indole-1-carboxylate (5c):

To a solution of (2-fluoro-4-iodophenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone (3c) (0.3 g, 0.75 mmol) and tertbutyl 3-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)1H-indole-1-carboxylate (4) (0.28 g, 0.82 mmol) in 1,4-dioxane (4.0 mL) was added 1.0 mL of water. The reaction mixture was degassed with argon for about 30 minutes. After that Pd(dppf)Cl2.DCM (0.030 g, 0.037 mmol) and Na2CO3 (0.16 g, 1.50 mmol) were added to the reaction mixture and again degassed with argon for another 20 minutes The reaction mixture was stirred under reflux for 3 h. After cooled down to room temperature, the mixture was extracted with EtOAc, washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (Hexane/EtOAc = 3:7) to afford 5c as a brown solid (0.31 g, 84.7%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.26 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.81(s, 1H), 7.59–7.56 (m, 1H), 7.46–7.40 (m, 2H), 7.30 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.11–7.06 (m, 1H), 4.68 (s, 1H), 3.64 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.43–1.40 (m, 1H), 3.28 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 2.32–2.29 (m, 1H), 1.84–1.82 (m, 1H), 1.76–1.73 (m, 2H), 1.72 (s, 9H), 1.60 (s, 1H), 1.54–1.47 (m, 1H), 1.43–1.37 (m, 1H), 1.28 (s, 3H), 1.15 (s, 3H), 1.09 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H).

(4-(1H-Indol-3-yl)-3-methoxyphenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone (1):

To a solution of tert-butyl 3-(2methoxy-4-(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octane-6carbonyl)phenyl)-1H-indole-1-carboxylate (5a) (0.47 g, 0.935 mmol) in methylene chloride (5 mL) was added trifluoroacetic acid (0.29 mL, 3.74 mmol) dropwise at 0 °C, and then, the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 8 h. After completion of the reaction, the reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (Hexane:EtOAc = 2:8) to give (4-(1Hindol-3-yl)-3-methoxyphenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone as a pale yellow solid (0.32 g, 85.1% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.38 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (s, 1H), 7.45 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.27 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.19–7.14 (m, 3H), 4.68 (s, 1H), 3.90 (s, 3H), 3.64 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.39–3.30 (m, 1H), 1.85–1.82 (m, 1H), 1.79–1.76 (m, 1H), 1.66 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.54–1.47 (m, 2H), 1.41–1.36 (m, 1H), 1.30–1.27 (m, 1H), 1.20 (s, 3H), 1.12 (s, 3H), 1.00 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H). 13CNMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.0, 156.4, 136.1, 129.9, 126.4, 124.9, 122.1, 120.3, 120.1, 118.9, 118.6, 112.4, 111.4, 110.1, 109.7, 58.3, 56.7, 55.6, 44.5, 44.1, 38.5, 36.3, 31.2, 30.3, 25.2. HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd [C26H31N2O2] [(M + H)]+ 403.2386, found 403.2380.

(3-Hydroxy-4-(1H-Indol-3-yl)phenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone (6a):

To a solution of tert-butyl 3-(2hydroxy-4-(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octane-6carbonyl)phenyl)-1H-indole-1-carboxylate (5b) (0.3 g, 0.61 mmol) in methylene chloride (3 mL) was added trifluoroacetic acid (0.19 mL, 2.45 mmol) dropwise at 0 °C, and then, the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 8 h. After completion of the reaction, the reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (Hexane:EtOAc = 2:8) to give (4-(1Hindol-3-yl)-3-methoxyphenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone as a white solid (0.2 g, 84.0% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.72 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 2H), 7.30 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 2H), 7.10–7.06 (m, 1H), 4.68 (s, 1H), 3.90 (s, 3H), 3.64 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.30 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.84–1.74 (m, 2H), 1.62 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.55–1.45 (m, 2H), 1.39–1.35 (m, 1H), 1.29–1.26 (m, 1H), 1.17 (s, 3H), 1.09 (s, 3H), 0.98 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.5, 153.4, 137.0, 136.5, 130.6, 126.1, 123.9, 122.8, 120.5, 119.7, 118.4, 114.0, 113.7, 111.7, 111.3, 64.5, 58.1, 56.4, 49.6, 38.5, 32.2, 30.0, 27.7, 25.4. HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd [C25H29N2O] [(M + H)]+ 389.2229, found 389.2223.

(2-Fluoro-4-(1H-Indol-3-yl)phenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone (6b):

To a solution of tertbutyl 3-(3-fluoro-4-(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octane-6-carbonyl)phenyl)1H-indole-1-carboxylate (5c) (0.3 g, 0.61 mmol) in methylene chloride (25 mL) was added trifluoroacetic acid (0.19 mL, 2.44 mmol) dropwise at 0 °C, and then, the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 8 h. After completion of the reaction, the reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (Hexane:EtOAc = 2:8) to give (4-(1Hindol-3-yl)-3-methoxyphenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone as a brown solid (0.19 g, 79.8% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.48 (s, 1H), 7.93 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.49–7.44 (m, 2H), 7.39–7.37 (m, 3H), 7.28 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.24–7.21 (m, 1H), 4.65 (s, 1H), 3.68 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.30 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.87–1.83 (m, 1H), 1.62 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.55–1.45 (m, 2H), 1.39–1.34 (m, 2H), 1.22 (s, 1H), 1.14 (s, 3H), 1.09 (s, 3H), 0.95 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H). HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd [C25H28FN2O] [(M + H)]+ 391.2186, found 391.2180.

(3-(2fluoroethoxy)-4-(1H-indol-3-yl)phenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6yl)methanone (6c):

To a solution of (3Hydroxy-4-(1H-Indol-3-yl)phenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone (6a) (0.1 g, 0.25 mmol) in DMF (1 mL) was added 2-Fluoroethyl tosylate (0.06 g, 0.28 mmol) and Cs2CO3 (0.125 g, 0.38 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight and then partitioned between EtOAc and brine. The organic layer was separated, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under a vacuum. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (EtOAc : Hexane = 7:3) to give 6c as a white solid (0.06 g, 54.05% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.51 (s, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.78–7.76 (m, 2H), 7.68 (s, 1H), 7.46 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.27–7.13 (m, 4H), 4.76 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 4.65 (s, 1H), 4.29 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 3.68 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H ), 3.30 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.87–1.83 (m, 1H), 1.62 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.55–1.45 (m, 2H), 1.39–1.34 (m, 2H), 1.22 (s, 1H), 1.17 (s, 3H), 1.09 (s, 3H), 0.99 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H). HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd [C27H32FN2O2] [(M + H)]+ 435.2448, found 435.2442.

4.1.1. General procedure for the synthesis of compounds 8a-l.

To a solution of iodo derivatives (3a, 3b and 3c, 1.0 mmol, 1 equiv) and boronic acids or esters (7, 1.5 mmol, 1.5 equiv) in 1,4-dioxane (4.0 mL) was added 1.0 mL of water. The reaction mixture was degassed with argon for about 30 minutes. After that Pd(dppf)Cl2.DCM (0.05 equiv, 0.05 mmol) and Na2CO3 (2 equiv, 2.0 mmol) were added to the reaction mixture and again degassed with argon for another 20 minutes. The reaction mixture was stirred under reflux for 3 h. After cooled down to room temperature, the mixture was extracted with EtOAc, washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (Silica, Hexane/EtOAc = 1:9 for 8a-b, 8h-j and 8l, Hexane/EtOAc = 7:3 for 8g and 8k and CH2Cl2/MeOH = 9:1 for 8c-f) (see Scheme 3).

(4-(6Fluoropyridin-3-yl)-3-methoxyphenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6yl)methanone (8a):

To afford yellow solid (0.072 g, 78.2%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.36 (s, 1H), 7.99 (t, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.33 (t, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.15–7.10 (m, 2H), 7.00 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 4.66 (s, 1H), 3.87 (s, 3H), 3.63 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.35 (t, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.84–1.81 (m, 1H), 1.68–1.62 (m, 2H), 1.56–1.48 (m, 2H), 1.40–1.38 (m, 1H), 1.29 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.18 (s, 3H), 1.10 (s, 3H), 0.98 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H). HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd [C23H28FN2O2] [(M + H)]+ 383.2135, found 383.2129.

(4-(2Fluoropyridin-3-yl)-3-methoxyphenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6yl)methanone (8b):

To afford yellow solid (0.075 g, 81.5%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.21 (s, 1H), 7.79 (t, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.31–7.24 (m, 2H), 7.11–7.06 (m, 2H), 4.64 (s, 1H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 3.61 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.33 (t, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.80–1.78 (m, 1H), 1.68–1.62 (m, 1H), 1.54–1.44 (m, 2H), 1.40– 1.34 (m, 2H), 1.28 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.16 (s, 3H), 1.08 (s, 3H), 0.96 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H). HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd [C23H28FN2O2] [(M + H)]+ 383.2135, found 383.2129.

(3Methoxy-4-(1-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)phenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6yl)methanone (8c):

To afford yellow solid (0.082 g, 82.0%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.82 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (s, 1H), 7.38 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.19–7.14 (m, 3H), 4.69 (s, 1H), 3.92 (s, 3H), 3.88 (s, 3H), 3.85 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.65 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.39–3.32 (m, 1H), 1.89–1.84 (m, 2H), 1.79–1.76 (m, 1H), 1.57–1.47 (m, 1H), 1.43–1.41 (m, 1H), 1.35 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.19 (s, 3H), 1.11 (s, 3H), 0.98 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H). HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd [C27H33N2O2] [(M + H)]+ 417.2542, found 417.2540.

(3Methoxy-4-(1H-pyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridin-3-yl)phenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6yl)methanone (8d):

To afford yellow solid (0.05 g, 51.5%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.31 (s, 1H), 8.23 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (s, 1H), 7.55 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.16–7.12 (m, 2H), 4.66 (s, 1H), 3.89 (s, 3H), 3.62 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.40–3.33 (m, 1H), 2.16 (s, 1H), 1.82–1.70 (m, 2H), 1.63–1.58 (m, 1H), 1.51–1.44 (m, 1H), 1.40–1.34 (m, 2H), 1.29 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.16 (s, 3H), 1.10 (s, 3H), 0.98 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H). HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd [C25H30N3O2] [(M + H)]+ 404.2338, found 404.2330.

(3Methoxy-4-(1H-pyrrolo[2,3-c]pyridin-3-yl)phenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6yl)methanone (8e):

To afford pale yellow solid (0.056 g, 57.7%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.31 (s, 1H), 8.23 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (s, 1H), 7.56 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.25 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.16–7.12 (m, 2H), 4.66 (s, 1H), 3.89 (s, 3H), 3.62 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.40–3.33 (m, 1H), 2.16 (s, 1H), 1.82–1.70 (m, 2H), 1.63–1.58 (m, 1H), 1.51–1.44 (m, 1H), 1.40–1.34 (m, 2H), 1.28 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.16 (s, 3H), 1.10 (s, 3H), 0.98 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H). HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd [C25H30N3O2] [(M + H)]+ 404.2338, found 404.2330.

(3Methoxy-4-(1H-pyrrolo[3,2-c]pyridin-3-yl)phenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6yl)methanone (8f):

To afford yellow solid (0.048 g, 49.4%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, MeOD) δ 8.32 (s, 1H), 8.27 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.27 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.20 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.17–7.15 (m, 1H), 4.57 (s, 1H), 3.92 (s, 3H), 3.62 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.28–3.26 (m, 1H), 1.92–1.87 (m, 1H), 1.70–1.61 (m, 2H), 1.56–1.49 (m, 1H), 1.43–1.41 (m, 2H), 1.35 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.18 (s, 3H), 1.10 (s, 3H), 0.98 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H). HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd [C25H30N3O2] [(M + H)]+ 404.2338, found 404.2330.

(2’-Methylbiphenyl-4-yl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone (8g):

To afford colorless semi solid (0.07 g, 77.8%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.53 (t, J = 10.0 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 2H), 7.30–7.28 (m, 2H), 7.24 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 2H), 4.68 (s, 1H), 3.65 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.39– 3.34 (m, 1H), 2.29 (s, 1H), 1.84–1.79 (m, 1H), 1.70–1.62 (m, 1H), 1.56–1.46 (m, 2H), 1.42–1.36 (m, 2H), 1.28 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.19 (s, 3H), 1.10 (s, 3H), 0.98 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H). HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd [C24H30NO] [(M + H)]+ 348.2327, found 348.2320.

(4-(3-Methylpyridin-4-yl)phenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone (8h):

To afford pale yellow solid (0.072 g, 80.0%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.52 (s, 1H), 8.48 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.56–7.53 (m, 2H), 7.38–7.35 (s, 2H), 7.14 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 4.65(s, 1H), 3.64 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1 H), 3.34–3.32 (m, 1H), 2.28 (s, 3H), 1.81–1.76 (m, 2H), 1.64–1.51 (m, 1H), 1.49–1.46 (m, 1H), 1.38– 1.34 (m, 2H), 1.28 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.16 (s, 3H), 1.08 (s, 3H), 0.97 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H). HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd [C24H29N2O] [(M + H)]+ 349.2280, found 349.2274.

(4-(4-Methylpyridin-3-yl)phenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone (8i):

To afford pale yellow solid (0.075 g, 83.3%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.48 (t, J = 10.0 Hz, 2H), 7.57 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H), 7.39–7.36 (m, 2H), 7.29 (s, 1H), 4.67 (s, 1H), 3.65 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.37–3.33 (m, 1H), 2.28 (s, 3H), 1.84–1.81 (m, 1H), 1.67–1.62 (m, 1H), 1.50–1.42 (m, 2H), 1.41–1.38 (m, 2H), 1.28 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.19 (s, 3H), 1.10 (s, 3H), 0.98 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H). HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd [C24H29N2O] [(M + H)]+ 349.2280, found 349.2274.

(4-(2-Methylpyridin-3-yl)phenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone (8j):

To afford pale yellow solid (0.069 g, 76.6%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.52 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.55–7.50 (m, 3H), 7.37–7.34 (m, 2H), 7.20 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 4.65 (s, 1H), 3.64 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.35– 3.31 (m, 1H), 2.51 (s, 3H), 1.82–1.78 (m, 1H), 1.65–1.60 (m, 1H), 1.54–1.44 (m, 2H), 1.40–1.34 (m, 2H), 1.25 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.16 (s, 3H), 1.08 (s, 3H), 0.97 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H). HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd [C24H29N2O] [(M + H)]+ 349.2280, found 349.2274.

(3-Fluoro-6’-methylbiphenyl-4-yl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone (8k):

To afford white yellow solid (0.072 g, 79.1%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.40–7.35 (m, 1H), 7.31– 7.28 (m, 2H), 7.25–7.23 (m, 1H), 7.21–7.19 (m, 1H), 7.16–7.13 (m, 1H), 7.08–7.04 (m, 1H), 4.66 (s, 1H), 3.65 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.31–3.29 (m, 1H), 2.28 (s, 3H), 1.84–1.81 (m, 1H), 1.62–1.58 (m, 1H), 1.50– 1.42 (m, 2H), 1.41–1.38 (m, 2H), 1.28 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.15 (s, 3H), 1.06 (s, 3H), 0.94 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H). HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd [C24H29FNO] [(M + H)]+ 366.2233, found 366.2228.

(2Fluoro-4-(4-methylpyridin-3-yl)phenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6-aza-bicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6yl)methanone (8l):

To afford yellow solid (0.075 g, 82.4%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.48 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 8.43 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.46–7.41 (m, 1H), 7.21 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.17–7.15 (m, 1H), 7.10–7.06 (m, 1H), 4.66 (s, 1H), 3.66 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.31–3.29 (m, 1H), 2.30 (s, 3H), 1.87–1.78 (m, 1H), 1.62–1.59 (m, 1H), 1.55–1.47 (m, 2H), 1.44–1.35 (m, 2H), 1.23 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.15 (s, 3H), 1.09 (s, 3H), 0.94 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 3H). HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd [C23H28FN2O] [(M + H)]+ 367.2186, found 367.2180.

Tert-butyl 3-(2-methoxy-4-(methoxycarbonyl)phenyl)-1H-indole-1-carboxylate (10):

To a solution of methyl 4-iodo-3-methoxybenzoate (9) (0.5 g, 1.71 mmol) and tert-butyl 3-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2dioxaborolan-2-yl)-1H-indole-1-carboxylate (0.70 g, 2.05 mmol) in 1,4-dioxane (10.0 mL) was added 2.0 mL of water. The reaction mixture was degassed with argon for about 30 minutes. After that Pd(dppf)Cl2.DCM (0.069 g, 0.085 mmol) and Na2CO3 (0.36 g, 3.42 mmol) were added to the reaction mixture and again degassed with argon for another 20 minutes. The reaction mixture was stirred under reflux for 3 h. After cooled down to room temperature, the mixture was extracted with EtOAc, washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (Hexane/EtOAc = 4:6) to afford 10 as a yellow solid (0.52 g, 79.7%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.15 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (s, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 2H), 7.56 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 2H), 7.32 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.28 (s, 1H), 3.86 (s, 3H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 1.62 (s, 9H).

Methyl 4-(1H-indol-3-yl)-3-methoxybenzoate (11):

To a solution of tert-butyl 3-(2methoxy-4(methoxycarbonyl)phenyl)-1H-indole-1-carboxylate (10) (0.5 g, 1.31 mmol) in methylene chloride (25 mL) was added trifluoroacetic acid (0.4 mL, 5.24 mmol) dropwise at 0 °C, and then, the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 8 h. After completion of the reaction, the reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (Hexane:EtOAc = 2:8) to give 11 as a yellow solid (0.32 g, 86.9% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.38 (s, 1H), 7.85 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (s, 2H), 7.70 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 2H), 7.47 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 3.98 (s, 3H), 3.96 (s, 3H).

4-(1H-Indol-3-yl)-3-methoxybenzoic acid (12):

A solution of methyl 4-(1Hindol-3-yl)-3methoxybenzoate (11) (0.3 g, 1.06 mmol) in THF/H2O (3:1 3 mL) was treated with lithium hydroxide monohydrate (0.22 g, 5.33 mmol) and stirred at room temperature for overnight. The reaction mixture was then acidified with 10% HCl to pH 4 and then partitioned between EtOAc and brine. The organic layer was separated, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (CH2Cl2:MeOH = 9:1) to give 4-(4methoxybenzyloxy)-3-nitrobenzoic acid as a pale yellow solid (0.25 g, 87.7% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO–d6) δ 11.44 (s, 1H), 7.74–7.70 (m, 3H), 7.64 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (s, 1H), 7.46 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.16–7.13 (m, 1H), 7.08 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H).

(4-(1H-Indol-3-yl)-3-methoxyphenyl)(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)methanone (13a):

To the mixture of 4(1H-indol-3-yl)-3-methoxybenzoic acid (12) (0.04 g, 0.15 mmol), 1-methyl piperazine (0.018 g, 0.18 mmol), EDC.HCl (0.034 g, 0.18 mmol), and HOBT (0.024 g, 0.18 mmol), in DMF (10 mL) was added DIPA (0.05 mL, 0.30 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight and then partitioned between EtOAc and brine. The organic layer was separated, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under a vacuum. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (CH2Cl2:MeOH = 9:1) to give 13a as a white solid (0.031 g, 59.6% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.39 (s, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.23–7.18 (m, 1H), 7.17–7.14 (m, 1H), 7.10 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.06 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 3.87 (s, 3H), 3.83–3.60 (m, 4H), 2.50–2.46 (m, 4H), 2.35 (s, 3H); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd [C21H24N3O2] [(M + H)]+ 350.1869, found 350.1863.

(4-(1H-Indol-3-yl)-3-methoxyphenyl)(4,4-difluoropiperidin-1-yl)methanone (13b):

To the mixture of 4-(1H-indol-3-yl)-3-methoxybenzoic acid (12) (0.04 g, 0.15 mmol), 4,4-difluoropiperidine hydrochloride (0.028 g, 0.18 mmol), EDC.HCl (0.034 g, 0.18 mmol), and HOBT (0.024 g, 0.18 mmol), in DMF (10 mL) was added DIPA (0.05 mL, 0.30 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight and then partitioned between EtOAc and brine. The organic layer was separated, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under a vacuum. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (CH2Cl2:MeOH = 9:1) to give 13b as a white solid (0.028 g, 50.9% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.33 (s, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.19–7.18 (m, 1H), 7.11 (m, 1H), 7.07 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 3.89 (s, 3H), 3.87–3.80 (m, 4H), 2.06–2.04 (m, 4H); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd [C21H21F2N2O2] [(M + H)]+ 371.1571, found 371.1566.

(4-(1H-Indol-3-yl)-3-methoxyphenyl)(4-methyl-1,4-diazepan-1-yl)methanone (13c):

To the mixture of 4-(1H-indol-3-yl)-3-methoxybenzoic acid (12) (0.04 g, 0.15 mmol), 1-methyl-1,4-diazepane (0.02 g, 0.18 mmol), EDC.HCl (0.034 g, 0.18 mmol), and HOBT (0.024 g, 0.18 mmol), in DMF (10 mL) was added DIPA (0.05 mL, 0.30 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight and then partitioned between EtOAc and brine. The organic layer was separated, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under a vacuum. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (CH2Cl2:MeOH = 9:1) to give 12c as a white solid (0.034 g, 62.9% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.42 (s, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.27–7.22 (m, 1H), 7.18–7.15 (m, 1H), 7.08–7.05 (m, 2H), 3.86 (s, 3H), 3.83–3.81 (m, 2H), 3.66 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 3.60 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 2.79 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 2.68 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 2.63–2.60 (m, 2H), 2.42 (s, 3H), 2.04 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 1.91 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd [C22H26N3O2] [(M + H)]+ 364.2025, found 364.2020.

N-Adamantan-1-yl-4-(1H-indol-3-yl)-3-methoxybenzamide (13d):

To the mixture of 4-(1Hindol-3yl)-3-methoxybenzoic acid (12) (0.04 g, 0.15 mmol), 1-Adamantylamine (0.027 g, 0.18 mmol), EDC.HCl (0.034 g, 0.18 mmol), and HOBT (0.024 g, 0.18 mmol), in DMF (10 mL) was added DIPA (0.05 mL, 0.30 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight and then partitioned between EtOAc and brine. The organic layer was separated, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under a vacuum. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (Hexane:EtOAc = 7:3) to give 13d as a white solid (0.03 g, 50.8% yield. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.37 (s, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.28–7.22 (m, 2H), 7.19–7.16 (m, 1H), 5.90 (s, 1H), 3.92 (s, 3H), 2.18–2.16 (m, 9H), 1.78–1.72 (m, 6H); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd [C26H29N2O2] [(M + H)]+ 401.2229, found 401.2224.

N-(4-Fluorophenyl)-4-(1H-indol-3-yl)-3-methoxybenzamide (13e):

To the mixture of 4-(1H-indol-3yl)-3-methoxybenzoic acid (12) (0.04 g, 0.15 mmol), 4-fluorobenzenamine (0.02 g, 0.164 mmol), EDC.HCl (0.034 g, 0.18 mmol), and HOBT (0.024 g, 0.18 mmol), in DMF (10 mL) was added DIPA (0.05 mL, 0.30 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight and then partitioned between EtOAc and brine. The organic layer was separated, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated under a vacuum. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (Hexane:EtOAc = 6:4) to give 13e as a brown solid (0.02 g, 37.7% yield). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.38 (s, 1H), 7.86–7.77 (m, 3H), 7.66–7.64 (m, 4H), 7.46 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 2H), 7.27 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 7.22–7.19 (m, 1H), 7.11–7.08 (m, 2H), 3.96 (s, 3H); HRMS (ESI+) m/z calcd [C22H18FN2O2] [(M + H)]+ 361.1352, found 361.1350.

4.1.2. Chiral HPLC separation of compound 1 and 6a.

Racemic 1 was separated into two enantiomers (1S,5R)-1 (tR 10.9 min; ee 98%) and (1R,5S)-1 (tR 13.9 min; ee 97%) by preparative chiral HPLC. Method: Chiralcel OD, 10×250 mm; mobile phase: hexane/2propanol 90/10; 8 mL/min; UV 254 nm. The chiral structure of the enantiomers that was determined previously22 was confirmed here by the V1a binding assay as described below. The enantiomeric purity of [11C](1S,5R)-1 (e.e.>95%) was tested under the same HPLC conditions.

Racemic compound 6a was separated into two enantiomers (1S,5R)-6a (tR = 3.5 min; ee 99.5%) and (1R,5S)-6a (tR ~ 6 min; ee 99.1%) by preparative supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) commercially (Averica, Marlborough, MA). Method: column: 2.1 × 25.0 cm Chiralpak AD-H from Chiral Technologies (West Chester, PA); CO2 co-solvent – ethanol; isocratic method: 50% co-solvent at 60 g/min; pressure: 85 bar, temperature: 25oC.

4.2. In vitro binding assay

of all vasopressin compounds was performed commercially by Eurofins CEREP (Celle L’Evescault, France) (assay number 0159) as described elsewhere [37]. Briefly, the assay conditions are shown in the Table below. Nonspecific binding was defined as that remaining in the presence of 1 µM AVP.

| Receptor | Source | Radiotracer | Conc. | KD | Incubation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (h)V1a | Human recombinant (CHO cells) | [3H]AVP | 0.3 nM | 0.5 nM | 60 min, RT |

The assays were done two times independently, each in duplicate, at selected concentrations of the test compounds. The binding assay results were analyzed using a one-site competition model, and IC50 curves were generated based on a sigmoidal dose response with variable slope. The Ki values were calculated using the Cheng–Prusoff equation.

4.3. Radiochemistry

[11C]iodomethane was prepared with the General Electric TRACERlab FX MeI (GE, Milwaukee, WI) using a GE PETtrace cyclotron.

4.3.1. Radiosynthesis of [1CH3](1S,5R)-1

A solution of 1 mg precursor (1S,5R)-6a ((3-hydroxy-4-(1H-indol-3-yl)phenyl)(1,3,3-trimethyl-6azabicyclo[3.2.1]octan-6-yl)methanone) in 0.2 mL DMSO was placed in a 1 mL V-vial and 1.0 mg K2CO3 was added. The mixture was sonicated for 5 min. [11C]iodomethane, carried by a stream of nitrogen, was trapped in the above solution of the precursor. The reaction was heated in an 80 °C water bath for 3.5 min, then quenched with 0.2 mL of water. The crude reaction product was purified by reverse-phase HPLC (column: Waters XBridge C18, 10 µ, 10×250 mm; mobile phase: acetonitrile/water/triethylamine 580/420/2; flow rate: 10 mL/min; UV: 254 nm). The radioactive peak (tR = 6.5 min) that was separated from the precursor (tR = 3.1 min) was collected in solution of 0.25 g ascorbic acid and 60 mL water. The water solution was passed through an activated Waters C-18 Oasis HLB light solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridge. After the SPE was washed with 10 mL of saline, the product was eluted with ethanol (1 mL) and diluted with 10 mL saline. The final product solution was analyzed by analytical HPLC (column: Waters Xbridge C18, 10 µ, 250×4.6 mm; mobile phase acetonitrile/water/triethylamine 70/30/1; flow rate: 3 ml/min; UV 254 nm). A single radioactive peak (tR = 3.2 min) corresponding to [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 was observed. The specific radioactivity at the end-ofsynthesis was calculated by relating radioactivity to the mass associated with the UV absorbance peak of carrier.

4.4. Animal studies.

Baseline study in CD1 mice:

Male, CD-1 mice weighing 25–27 g from Charles River (Wilmington, MA) were used. The animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation at 5, 15, 30 and 60 min following injection of 3.7 MBq (0.1 mCi) [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 (specific radioactivity = 232 GBq/µmole (8,600 mCi/µmol) in 0.2 mL saline into a lateral tail vein (n = 3). The brains were removed and dissected on ice. Septum, cortex, hippocampus, and the rest of brain were weighed and their radioactivity content was determined in a γ-counter LKB/Wallac 1283 CompuGamma CS (Perkin Elmer, Bridgeport, CT). Aliquots of the injectate were prepared as standards and their radioactivity content was determined along with the tissue samples. The percent of injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g tissue) was calculated.

Blocking of [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 binding in CD1 mice:

In vivo binding specificity (blocking) studies were carried out by subcutaneous (SC) administration of various doses (0 mg/kg, 0.3 mg/kg, 1 mg/kg, 3 mg/kg) of ligand 8g followed by IV injection of 3.7 MBq (0.1 mCi) [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 30 min thereafter (n = 3). Thirty minutes after administration of the radiotracer the animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, brain tissues were harvested, and their radioactivity content was determined.

4.4.1. Effect of anesthetics on the [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 binding in CD1 mice:

The study was performed similarly to the blocking experiments with CD1 mice. All anesthetics were injected ip (80 mg/kg), 30 min prior the radiotracer.

4.4.2. Brain regional distribution of [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 in prairie voles:

male, prairie voles weighing 47–58 g from Kinsey Institute Indiana University (Bloomington, IN) were used. The experiments were performed similarly to the experiments with CD1 mice. The radiotracer was injected into retro-orbital venous sinus under a brief isoflurane anesthesia [38].

Highlights.

A series of V1a ligands was prepared for positron-emission tomography (PET).

A new V1a PET tracer [11C](1S,5R)-1 was synthesized and evaluated in rodents.

[11C](1S,5R)-1 specifically labels V1a in the mouse and prairie vole brain.

The anesthetic Propofol blocks the uptake of [11CH3](1S,5R)-1 in the mouse brain.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported in part by NIH grant R01MH107197 (Wong, Horti), John Davis Foundation grant and Division of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. We thank Paige Finley and Polina Sysa Shah for the help with animal experiments and Julia Buchanan for editorial comments.

ABBREVIATIONS

- PET

positron emission tomography

- ADH

antidiuretic hormone

- AVP

arginine vasopressin

- DMF

N,Ndimethylformamide

- DIPEA

N,N-Diisopropylethylamine

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- [1].Ishikawa S, Cellular actions of arginine vasopressin in the kidney, Endocrine Journal 40 (1993) 373–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Silva YJ, Moffat RC, Walt AJ, Vasopressin effect on portal and systemic hemodynamics. Studies in intact, unanesthetized humans, JAMA Journal 210 (1969) 1065–1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Johnson ZV, Young LJ, Oxytocin and vasopressin neural networks: Implications for social behavioral diversity and translational neuroscience, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 76 (2017) 87–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Gobrogge K, Wang Z, The ties that bond: neurochemistry of attachment in voles, Current Opinion in Neurobiology 38 (2016) 80–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Winslow JT, Hastings N, Carter CS, Harbaugh CR, Insel TR, A role for central vasopressin in pair bonding in monogamous prairie voles, Nature 365 (1993) 545–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Dumais KM, Veenema AH, Vasopressin and oxytocin receptor systems in the brain: Sex differences and sex-specific regulation of social behavior, Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 40 (2016) 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Veenema AH, Neumann ID, Central vasopressin and oxytocin release: regulation of complex social behaviours, Progress in Brain Research 170 (2008) 261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Koshimizu TA, Nakamura K, Egashira N, Hiroyama M, Nonoguchi H, Tanoue A, Vasopressin V1a and V1b receptors: from molecules to physiological systems, Physiological Reviews 92 (2012) 1813–1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Albers HE, Species, sex and individual differences in the vasotocin/vasopressin system: relationship to neurochemical signaling in the social behavior neural network, Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 36 (2015) 49–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Zhang R, Zhang HF, Han JS, Han SP, Genes Related to Oxytocin and ArginineVasopressin Pathways: Associations with Autism Spectrum Disorders, Neuroscience Bulletin 33 (2017) 238–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Yirmiya N, Rosenberg C, Levi S, Salomon S, Shulman C, Nemanov L, Dina C, Ebstein RP, Association between the arginine vasopressin 1a receptor (AVPR1a) gene and autism in a familybased study: mediation by socialization skills, Molecular Psychiatry 11 (2006) 488–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Insel TR, Wang ZX, Ferris CF, Patterns of brain vasopressin receptor distribution associated with social organization in microtine rodents, The Journal of Neuroscience 14 (1994) 5381–5392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Johnson AE, Audigier S, Rossi F, Jard S, Tribollet E, Barberis C, Localization and characterization of vasopressin binding sites in the rat brain using an iodinated linear AVP antagonist, Brain Research 622 (1993) 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Young LJ, Toloczko D, Insel TR, Localization of vasopressin (V1a) receptor binding and mRNA in the rhesus monkey brain, Journal of Neuroendocrinology 11(1999) 291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Loup F, Tribollet E, Dubois-Dauphin M, Dreifuss JJ, Localization of high-affinity binding sites for oxytocin and vasopressin in the human brain. An autoradiographic study. Brain Research 555 (1991) 220–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Landgraf R, Neumann ID, Vasopressin and oxytocin release within the brain: a dynamic concept of multiple and variable modes of neuropeptide communication, Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 25 (2004) 150–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Heinrichs M, von Dawans B, Domes G, Oxytocin, vasopressin, and human social behavior. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 30 (2009) 548–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bielsky IF, Hu SB, Szegda KL, Westphal H, Young LJ, Profound impairment in social recognition and reduction in anxiety-like behavior in vasopressin V1a receptor knockout mice, Neuropsychopharmacology 29 (2004) 483–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Egashira N, Tanoue A, Higashihara F, Mishima K, Fukue Y, Takano Y, Tsujimoto G, Iwasaki K, Fujiwara M, V1a receptor knockout mice exhibit impairment of spatial memory in an eight-arm radial maze, Neuroscience Letters 356 (2004) 195–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Umbricht D, Del Valle Rubido M, Hollander E, McCracken JT, Shic F, Scahill L, Noeldeke J, Boak L, Khwaja O, Squassante L, Grundschober C, Kletzl H, Fontoura P, A Single Dose, Randomized, Controlled Proof-Of-Mechanism Study of a Novel Vasopressin 1a Receptor Antagonist (RG7713) in High-Functioning Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder, Neuropsychopharmacology (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [21].Fabio K, Guillon C, Lacey CJ, Lu SF, Heindel ND, Ferris CF, Placzek M, Jones G, Brownstein MJ, Simon NG, Synthesis and evaluation of potent and selective human V1a receptor antagonists as potential ligands for PET or SPECT imaging, Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 20 (2012) 1337–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Crombie AL, Antrilli TM, Campbell BA, Crandall DL, Failli AA, He Y, Kern JC, Moore WJ, Nogle LM, Trybulski EJ, Synthesis and evaluation of azabicyclo[3.2.1]octane derivatives as potent mixed vasopressin antagonists, Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 20 (2010) 3742–3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Eckelman WC, Reba RC, Gibson RE, Receptor-binding radiotracers: A class of potential radiopharmaceuticals, Journal of Nuclear Medicine 20 (1979) 350–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Freeman SM, Smith AL, Goodman MM, Bales KL, Selective localization of oxytocin receptors and vasopressin 1a receptors in the human brainstem, Social Neuroscience (2016) 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [25].Saito R, Ishiharada N, Ban Y, Honda K, Takano Y, Kamiya H, Vasopressin V1 receptor in rat hippocampus is regulated by adrenocortical functions, Brain Research 646 (1994)170–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Szot P, Myers KM, Dorsa DM, Effect of vasopressin administration and deficiency upon 3H-AVP binding sites in the CNS and periphery during development, Peptides 13 (1992) 389–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Tribollet E, Barberis C, Jard S, Dubois-Dauphin M, Dreifuss JJ, Localization and pharmacological characterization of high affinity binding sites for vasopressin and oxytocin in the rat brain by light microscopic autoradiography, Brain Research 442 (1988) 105–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Szot P, Ferris CF, Dorsa DM, [3H]arginine-vasopressin binding sites in the CNS of the golden hamster, Neuroscience Letters 119 (1990) 215–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Waterhouse RN, Determination of lipophilicity and its use as a predictor of blood-brain barrier penetration of molecular imaging agents. Molecular Imaging Biology 5 (2003) 376–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Horti AG, Raymont V, Terry GE, In PET and SPECT of Neurobiological Systems Book chapter 11 (2014) 251–319 (Springer; ). [Google Scholar]

- [31].Dubois-Dauphin M, Barberis C, de Bilbao F, Vasopressin receptors in the mouse (Mus musculus) brain: sex-related expression in the medial preoptic area and hypothalamus, Brain Research 743 (1996) 32–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chappell AR, Freeman SM, Lin YK, LaPrairie JL, Inoue K, Young LJ, Hayes LD, Distributions of oxytocin and vasopressin 1a receptors in the Taiwan vole and their role in social monogamy, Journal of Zoology (1987) 299 (2016) 106–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Turner LM, Young AR, Rompler H, Schoneberg T, Phelps SM, Hoekstra HE, Monogamy evolves through multiple mechanisms: evidence from V1aR in deer mice, Molecular Biology and Evolution 27 (2010) 1269–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Tanabe K, Kozawa O, Matsuno H, Niwa M, Dohi S, Uematsu T, Effect of propofol on arachidonate cascade by vasopressin in aortic smooth muscle cells: inhibition of PGI2 synthesis, Anesthesiology 90 (1999) 215–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Tanaka K, Suzuki M, Sumiyoshi T, Murata M, Tsunoda M, Kurachi M, Subchronic phencyclidine administration alters central vasopressin receptor binding and social interaction in the rat, Brain Research 992 (2003) 239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Le Melledo JM, Baker GB, Neuroactive steroids and anxiety disorders, Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience 27 (2002) 161–165. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Tahara A, Saito M, Sugimoto T, Tomura Y, Wada K, Kusayama T, Tsukada J, Ishii N, Yatsu T, Uchida W, Tanaka A, Pharmacological characterization of the human vasopressin receptor subtypes stably expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells, British Journal of Pharmacology 125 (1998) 1463–1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Yardeni T, Eckhaus M, Morris HD, Huizing M, Hoogstraten-Miller S, Retro-orbital injections in mice, Lab Animal (NY) 40 (2011) 155–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]