Abstract

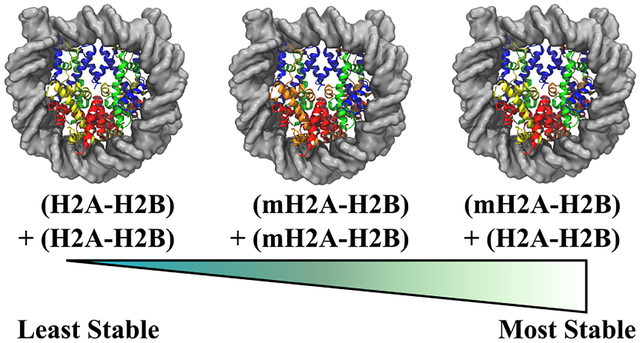

The fundamental unit of eukaryotic chromatin is the nucleosome core particle, a protein/DNA complex that binds ~147 base pairs of DNA to a histone octamer. These histones—H3, H4, H2A,H2B—form the nucleosome core through a stacked interaction in which two H2A−H2B dimers flank the (H3−H4)2 tetramer. In vivo, genetic accessibility can be modulated by the substitution of canonical histones with variant proteins that contain the same structural motif but a different amino acid sequence, such as the transcriptional repression-associated macroH2A variant. Previously, Chakravarthy and Luger published a crystal study that showed that H2A substitution is not necessarily required of both H2A moieties, but that in vitro recombination of nucleosomes in the presence of both macroH2A and H2A histone folds results in a hybrid macroH2A− H2A nucleosome with one dimer of each type. Here, we present molecular dynamics simulations of this hybrid construct and compare the results to our previous study on homogeneous H2A- and macroH2A-containing nucleosomes. We find that the hybrid contains a unique set of dynamics that stabilize the interactions between protein constituents and create an altogether more stable nucleosome, both in terms of protein−DNA and protein−protein binding. While dimer−tetramer interactions are asymmetric, as the difference in moieties would suggest, we observe that it is the canonical dimer that is pulled further into the nucleosome core, resulting in more secure dimer−tetramer bonds and a more stable histone core, and we also find significantly more interaction between the dimer subunits. Together, these models provide evidence for hybrid H2A−macroH2A nucleosome formation being not only possible but actually energetically more favorable than a homogeneous construct, with dynamics that are unique from their homogeneous H2A or macroH2A nucleosome counterparts. These effects of hybrid substitution likely propagate into higher-order chromatin structures to hinder transcriptional activity.

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

Eukaryotic organisms store their genetic code in the highly packaged structure of chromatin. The fundamental unit of chromatin is the nucleosome core particle (NCP), where ~147 base pairs of DNA are wrapped around a protein core containing eight histones: two copies each of H3, H4, H2A, and H2B.1–3 In the core, these proteins are arranged as an octamer in which two H2A−H2B dimers flank a tetramer composed of two H3−H4 dimers.4 Although these histones have minimal sequence identity, they all obey the same motif in which three α-helices are connected by disorderd loops (α1-L1-α2-L2-α3). Interactions between the dimers and the tetramer occur in two key locales: the four-helix bundle formed between H4 and H2B and an extended “docking domain” site between H2A and regions of both H3 and H4.4,5 In contrast, only one interaction between the dimers exists, specifically at the interface between H2A L1 loops.4,6

In vivo, cells alter the chemical composition of the NCP through post-translationally modifying histone residues and by the complete substitution of a canonical histone with a variant protein that possesses the same structural motif but with a modified chemical sequence.7–12 Of the four core proteins, H3 and H2A have more identified variants than H4 or H2B. While the histone fold sequences vary significantly across the H2A family (~50−60% identity to canonical H2A, depending on the variant),10 each variant possesses a modified L1 sequence, highlighting the importance of different L1−L1 interfaces for disparate cellular functions.13 Indeed, most H2A variants can be associated with specific changes in chromatin accessibility and transcriptional activity.10,14–17

The macroH2A variant was first identified in the inactive female sex chromosome (Xi) and is so named for the additional macrodomain that is connected to the histone core via a flexible, highly basic, linker sequence.5,18,19These additional domains have been shown to play several roles, such as replacing the need for linker histone H1,20–22 invoking interactions with external proteins in heterochromatin, and inhibiting PARP1-dependent processes.23 However, previous studies have shown that substituting canonical H2A with histone core-only macroH2A species is sufficient for producing more stable complexes in vitro,5,24 as well as for localization in Xi in vivo.13 Because of its involvement in transcriptional repression, macroH2A enrichment and depletion have been linked to regulation of pluripotent and cancerous cells.25,26

While the effects of macroH2A substitution continue to be studied, there has been very little focus on the necessary quantities of macroH2A required to invoke each of these observed mechanisms. That is to say, do both dimers need to be substituted with macroH2A, or is the replacement of a single dimer sufficient? A crystallographic and biochemical study by Chakravarthy and Luger seems to suggest as such, since they observed that NCPs preferentially form into hybrid constructs containing one moiety of H2A−H2B and another of macroH2A−H2B in the presence of both histone folds, and they further found that both the homogeneous and hybrid macroH2A octamers were resistant to action by the nucleosome assembly protein 1 (NAP1) chromatin remodeller in vitro.24 Previously, we conducted comparative molecular dynamics (MD) simulations on the stability, dynamics, and mechanisms of NCPs with fully substituted macroH2A histone core domains, as well as a fully substituted H2A mutant that possessed a macroH2A L1 loop sequence in an otherwise canonical H2A protein.27 In that study, we found that the macroH2A L1 sequence created a cascade of dynamics that stabilized the NCP complex by altering both protein−protein and protein−DNA interactions. Here, we conducted additional simulations on the hybrid NCP, containing one H2A dimer and one macroH2A dimer, to determine the extent at which macroH2A substitution invokes these previously observed mechanisms (see Figure 1). Our models show that the hybrid NCP samples its own unique array of dynamics, rather than sampling substates of the homogeneous macroH2A and canonical H2A complexes. Interactions between the hybrid dimers are strongly increased compared to both these systems, and hybrid NCPs are observed to be more stable in terms of both DNA-binding capability and complex assembly. These data support a model in which chromatin stabilization and gene silencing can be achieved through the substitution of a single macroH2A−H2B dimer.

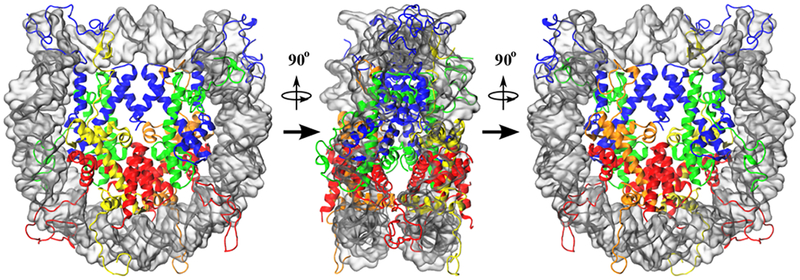

Figure 1.

Simulated conformation of the hybrid NCP, containing one moiety of canonical H2A (yellow) and one moiety of macroH2A (orange). Each moiety forms a dimer with H2B (red), and they together flank the tetramer composed of two copies each of H3 (blue) and H4 (green). DNA is shown as a transparent silver surface, for visibility. While this construct has the same overall structure as the homogeneous canonical H2A and macroH2A nucleosomes, the separate H2A moieties break the twofold pseudosymmetry of the particle, in terms of sequence.

2. METHODS

2.1. System Construction.

Initial coordinates for the hybrid NCP system were taken from the crystal structure (PDB ID: 2F8N).24 Missing tail residues were constructed using the histone tails of the 1.9 Å resolution crystal as a model, and non-macroH2A proteins were mutated to match the sequence of the those histones,6 in accordance to our previous protocol.27 To ensure that differences between the hybrid and homogeneous NCPs are not a result of differences in DNA length, the crystallographic 146 bp of DNA in the hybrid NCP was substituted with the 147 bp sequence of the higher-resolution canonical NCP (protein data bank (PDB) identification (ID): 1KX56).

The system was then neutralized and solvated in a TIP3P box of 150 mM NaCl that extended at least 10 Å from the solute in each direction.28 As a result, the hybrid NCP system contained ~250 000 atoms, in agreement with the previous systems. The protein and DNA parameters were selected from the AMBER12SB fixed point-charge force field, and ions were parametrized according to the modifications of Joung and Cheatham.29–31 The system was then simulated using the NAMD engine (v2.10) three times according to the same protocol that we used previously.27,32 First, the system was energy minimized for 10 000 steps, 5000 steps with protein and DNA heavy atoms restrained according to a harmonic potential with a force constant of 10 kcal/mol/Å2 and 5000 steps without any restraints. Then, each simulation was heated from 10 to 300 K over 6 ps in the NVT ensemble,33 where the heavy atom restraints were reinstated. After it reached 300 K, the restraints of each simulation were gradually released over the course of 600 ps in the NPT ensemble, with a target pressure of 1 atm.34,35 Once the restraints were released, each simulation was then conducted for an additional 250 ns. In all stages of the simulation, bonds containing hydrogen were restrained via the RATTLE algorithm, allowing for a 2 fs time step.36 Long-range electrostatics were handled by Particle Mesh Ewald method,37,38 and short-range interactions were calculated according to a 10 Å cutoff, where a switching function was engaged at 8 Å.

2.2. Simulation Analysis.

Simulations were visualized with a mixture of VMD and PyMol.39,40 System equilibration was monitored according to root-mean-squared deviation (RMSD) of atomic positions for core protein and DNA backbone atoms, after being least-squares fit to the initial conformation. When measuring the separation distance between H2A α2 helices, the center of mass for the terminal four residues (first and last turns of the helix) were used. Both of these measurements were conducted within the cpptraj program of the Amber suite (v16).41 DNA binding energies were estimated according to a molecular mechanics generalized born surface area (MM-GB/SA) calculation.42 Similarly, NCP complex assembly was determined from the piecewise deconstruction of the NCP molecule, and the interaction strength between the L1 loops was determined as the sum of residue-pair contributions to the MM-GB/SA-calculated binding energy of each dimer to the hexasome complex. In this calculation, each dimer was calculated separately, and the reported values are representative of the average of the two. In all MM-GB/SA calculations, the highly dynamic histone tails were stripped from the calculation, as they are heavily undersampled.43–45

Allosteric effects of dimer substitution were probed using two different calculations. Changes in dynamics at a per-residue level were monitored by calculating the Kullback−Leibler divergence of dihedral angle samplings.46 Changes in residue-pair correlations were analyzed using the generalized correlation approach, which is based on the mutual information metric of information theory.47 The reported correlation coefficients are calculated from the largest linear mutual information value observed between the heavy atoms of each residue. For these correlations, each trajectory was analyzed separately, and the reported correlation matrices are the average across the three simulations. Furthermore, the shortest allosteric networks between all residue pairs were determined through a graph theory approach, where the correlation matrices were combined with contact maps to create connections in the graph. The importance of any residue within these networks were determined from their “betweenness centrality” metrics:48,49

| (1) |

where Bi is the betweenness centrality of residue n, N is the total number of pathways in the system, and σi,j is 1 if residue n exists in the path between residues i and j and 0 otherwise.

3. RESULTS

In this study, we performed three independent 250 ns simulations of the hybrid NCP containing one dimer of H2A−H2B and one dimer of macroH2A−H2B. We observe that the NCP core equilibrates on a similar time scale to that of the homogeneous NCP systems that we previously studied.27 However, the systems equilibrate to a slightly higher RMSD from the initial coordinates than in the homogeneous cases (~3.5 vs ~2.5 Å, Figure S1). This increase may be a result of the mutations that were introduced to the hybrid crystal structure to ensure that the discrepancies observed in structure and dynamics were not a result of protein or DNA sequence variation.

3.1. Hybrid NCPs Contain Unique Dynamics.

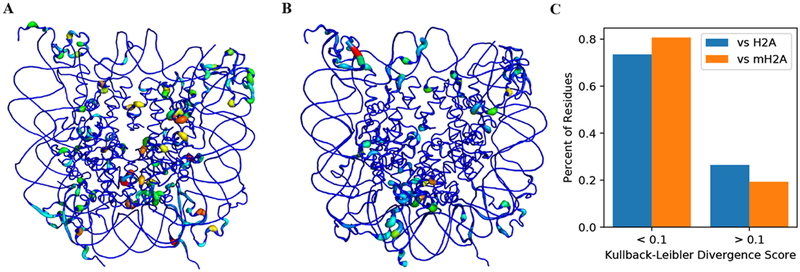

Dynamics at the individual residue level were probed using the Kullback−Leibler divergence of residue dihedral populations. This calculation is done at a per-residue level, with no knowledge of other residues. Distributions were compared against both the homogeneous canonical (Figure 2A) and macroH2A (Figure 2B) nucleosomes, and we observe that there are significant differences in sampling between the hybrid construct and either the canonical or macroH2A NCPs. Against both references, the sections of largest divergence can be separated into three regions: residues in or near the histone tails, residues within an H2A moiety of the opposing variant (i.e., residues in macroH2A moiety of the hybrid compared to the canonical H2A NCP), and the L1−L1 interface. The large divergences in the tails can be explained by the high degree of conformational heterogeneity available to energetically degenerate tail states,43 and these effects likely have little to no influence from the differences in core H2A composition. Furthermore, the overall difference in local sampling between the dimer moieties is still maintained, regardless of which dimer is selected from the homogeneous system, suggesting that the nucleosome may be agnostic to the selection of the H2A−H2B moiety that should be substituted with the macroH2A−H2B dimer.

Figure 2.

Kullback−Leibler divergence values for per-residue comparisons of dihedral sampling of residues in the hybrid NCP compared to the homogeneous (A) canonical and (B) macroH2A NCPs, as well as (C) the populations of residues in the hybrid NCP that show appreciable differences with the homogeneous canonical (blue) and macroH2A (gold) NCPs. In the three-dimensional mapping of values, wider, more colorful residues have larger divergence values, and narrower, bluer residues sample similar spaces between the two systems. Dynamic differences in the C-and N-terminal tails are largely a result of their wide arrangement of potential configurations, and they are therefore undersampled. However, the divergence values for core residues show that the hybrid NCP is more macroH2A-like than canonical-like at many locales. Compared to both systems, there are large sampling divergences at the L1−L1 interface due to the heterogeneous sequence at that locale.

While we observe differences in local sampling when comparing against either homogeneous NCP, we note that the hybrid dynamics, on the whole, are more similar to those of the macroH2A NCP (Figure 2). When compared to the canonical NCP dihedral sampling, 194 nontail residues possessed Kullback−Leibler divergence values greater than or equal to 0.1, which corresponds to 26.6% of the 730 possible nontail residues. In contrast, only 19.3% (141 residues) contained divergence values greater than or equal to 0.1 when comparing to the macroH2A NCP. A significance evaluation on these populations shows that this difference of 7.3% (53 residues) is statistically significant, with a p-value less than 0.001 (see Supporting Information).50 These data suggest that the hybrid NCP contains unique dynamics, but they are slightly more similar to the macroH2A system than the canonical system.

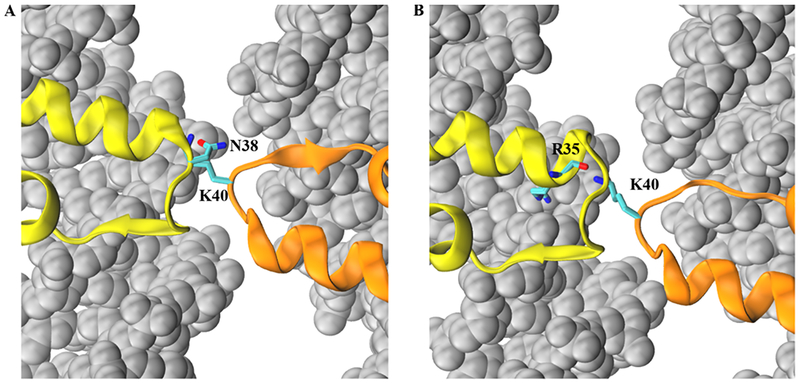

The largest region of dynamical difference in the NCP core from either the canonical or macroH2A systems occurred in the L1 loops. Previously, we observed that NCPs containing the macroH2A sequence in both L1 loops displayed disparate dynamics from the canonical loops in that the positively charged K40 residue formed a direct electrostatic interaction with the neighboring DNA. The canonical L1 loops contain no positively charged residues and instead possess a net negative charge (E41), and they cannot therefore capture this dynamic. Theoretically, one might expect that the hybrid NCP, possessing one positive loop and one negative loop, might sample between two states: one with the K40-DNA interaction state and another in a K40−E41 L1 loop interaction. However, this is not the case, as the K40−DNA interaction is unobserved on the hundreds of nanoseconds time scale. Furthermore, our models show very little interaction between charged side chains of the K40 and E41 residues (~3.5% of frames). Instead, K40 interacts primarily with the polar side chain of the canonical L1 loop N38 residue (24.4% of frames) and the backbone carbonyl of an L1-adjacent R35 residue (17.6%) (Figure 3). This cross-L1 interaction stabilizes the interface, resulting in consistently more interdimer contacts than either homogeneous system (Table 1, Figure S2C). Furthermore, the lost K40−DNA interaction is instead recaptured by neighboring arginine residues (~70% of frames).

Figure 3.

Representative conformations of the (A) K40−N38 and (B) K40−R35 hydrogen-bonding interactions in the hybrid simulations. The macroH2A moiety is shown in orange (K40 side chain as licorice, colored by atom type), while the canonical H2A moiety is represented in yellow (N38 side chain, R35 backbone and side chain as licorice, colored by atom type) is represented in yellow. The K40−N38 interaction (24.4% of all simulated frames) is directly between L1 loop residues, whereas the K40−R35 interaction (17.6% of frames) is an interaction between the macroH2A loop and an L1 loop-adjacent residue. In the homogeneous macroH2A NCP, the K40 residue predominantly interacts with neighboring DNA residues (background, silver spheres). Non-H2A family histones are not visualized for clarity.

Table 1.

Number of Contactsa

| Frequency cutoff | Hybrid H2A-H2B | Hybrid macroH2A-H2B | Inter- dimer | canonical dimer 1 | canonical dimer 2 | Inter- dimer | macroH2A dimer1 | macroH2A dimer2 | Inter- dimer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.6 | 19 | 19 | 3 | 22 | 19 | 1 | 17 | 20 | 0 |

| 0.65 | 17 | 15 | 3 | 18 | 18 | 1 | 16 | 16 | 0 |

| 0.7 | 17 | 12 | 3 | 16 | 16 | 1 | 14 | 15 | 0 |

| 0.75 | 17 | 12 | 2 | 15 | 13 | 0 | 13 | 10 | 0 |

| 0.8 | 16 | 11 | 1 | 13 | 11 | 0 | 10 | 9 | 0 |

Observed between each (macro)H2A−H2B dimer and the core tetramer, as well as between dimer moieties, in each simulation using several frequency cutoffs and distance requirement of 3.5 Å between heavy atoms in each residue-pair contact. Canonical dimers in the hybrid simulations possess more contacts with the tetramer with increasing stringency of the frequency cutoff. To a slightly lesser extent, the same trend is seen between identically positioned moieties in the homogeneous systems. Contacts between the hybrid canonical dimer are also observed to be more robust than the identically placed dimer in the canonical simulations, and the macroH2A moiety displays the same effect. At every frequency cutoff, the hybrid system possesses the largest number of inter-dimer contacts.

Using an MM-GB/SA analysis, we calculated the effect of these different dynamics on the interaction strength between the L1 loops, and we found that the L1 loops interact favorably in all three systems (Table 2), with the strongest interaction occurring between the hybrid loops (ΔGL1−L1 = −16.1 ± 0.1 kcal/mol) and the weakest occurring between canonical loops (ΔGL1−L1 = −10.3 ± 0.1 kcal/mol). Indeed, even though the L1 arrangements in the canonical construct maintain two negatively charged glutamic acids in close vicinity to one another, the net interaction is still favorable. While the macroH2A loops also contain two identically charged loops, the lysine−DNA interaction pulls the like charges apart, thereby yielding a more stable arrangement (ΔGL1−L1 = −12.0 ± 0.1). Although the charged residues in the hybrid loops (lysine in the macroH2A, glutamic acid in the canonical) rarely interact directly, the close vicinity of the opposite residues contribute favorably, along with the K40−N38 side chain interaction, to yield a stronger free energy of interaction than in either homogeneous construct.

Table 2.

MM-GB/SA Estimated DNA-Octamer Binding (ΔGDNA‑binding), Assembly (ΔGassembly), and L1−L1 Interaction (ΔGL1−L1) Energiesa

| system | ΔGDNA-binding | ΔΔGDNA- binding | ΔGassembly | ΔΔGassembly | ΔGdimer 1 | ΔGdimer 2 | ΔGL1-L1 | ΔΔGL1-L1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hybrid | −462.7 ± 5.2 | −34.1 ± 7.6 | −679.1 ± 6.3 | −60.5 ± 8.6 | −115.3 ± 0.4 | −104.4 ± 0.4 | −16.1 ± 0.1 | −5.8 ± 0.1 |

| canonical27 | −428.6 ± 5.6 | −618.6 ± 5.8 | −106.6 ± 2.5 | −101.1 ± 3.0 | −10.3 ± 0.1 | |||

| macroH2A27 | −434.5 ± 7.9 | −5.9 ± 9.7 | −637.1 ± 7.9 | −18.5 ± 9.8 | −104.0 ± 3.1 | −100.9 ± 3.7 | −12.0 ± 0.1 | −1.7 ± 0.1 |

In all measurements, the hybrid construct is more stable than either homogeneous complex, but the macroH2A construct is also more stable than the standard nucleosome. Also included are the MM-GB/SA determined values for dimer−hexamer binding energies for each dimer moieity (ΔGdimer 1 and ΔGdimer 2). Dimers are labelled according to their location (i.e., bound to entry or exit superhelical turn) within the nucleosome, and labels are therefore consistent across all nucleosomes complexes. In the hybrid construct, this corresponds to the canonical dimer occupying the “dimer 1” position and the macroH2A dimer occupying the “dimer 2” position. While the binding energy for the macroH2A dimer in the hybrid construct is in good agreement with values of homogeneously substituted dimers, the canonical dimer in the hybrid system is bound significantly more favorably than in the canonical NCP. All values are reported in kilocalories per mole.

3.2. Single Dimer Substitution Creates a Unique Dimer Realignment.

We previously observed that the increased hydrophobic bulk in the L1 loops upon macroH2A substitution realigned the (macro)H2A dimer orientations and altered the underlying contact network of the NCP. To demonstrate this realignment, we measured the separation between the bases and tops of the H2A α2 helices, which span the full distance from the L1−L1 interface (the “base” of the helix) to a region adjacent to the dimer−tetramer interaction site (the “top” of the helix). In the homogeneous complexes, we observed that substitution of macroH2A yielded an increase in base separation (34.8 ± 0.1 Å in canonical, 36.2 ± 0.1 Å in macroH2A) but a reduction in the distance between the tops of the helices (67.1 ± 0.1 Å in canonical, 66.2 ± 0.1 Å in macroH2A).27 Here, we find that the bases of the helices are separated by 34.9 ± 0.1 Å in the hybrid NCP, and the tops of the helices are separated by 66.3 ± 0.1 Å. Interestingly, these measurements classify a dimer rearrangement that is canonical-like in the base separation but macroH2A-like in the top separation, meaning that the dimers are more tightly drawn together in both measurements. This serves to stabilize interactions between both the dimers and between each dimer and the tetramer.

To better quantify the effect of dimer realignment on dimer−tetramer and dimer−dimer interactions, we monitored the number of contacts formed between each fragment as a function of the frequency criteria strictness (heavy-atom separation less than or equal to 3.5 Å; Table 1 and Figure S2). In the hybrid simulation, we find that the number of contacts between the canonical H2A−H2B moiety and the tetramer are comparable to the number of contacts between either dimer in the canonical NCP at less stringent frequency criteria (f ≤ 0.7), but more contacts are retained in the hybrid system at more stringent frequencies (f ≥ 0.75). A similar, but less drastic, effect can be seen for the macroH2A dimer moiety. Moreover, the number of contacts formed between dimers is consistently greater in the hybrid system than in either homogeneous construct, in good agreement with the MM-GB/ SA calculations of L1−L1 interaction discussed previously.

3.3. Single Dimer Substitution and Nucleosome Allosteric Networks.

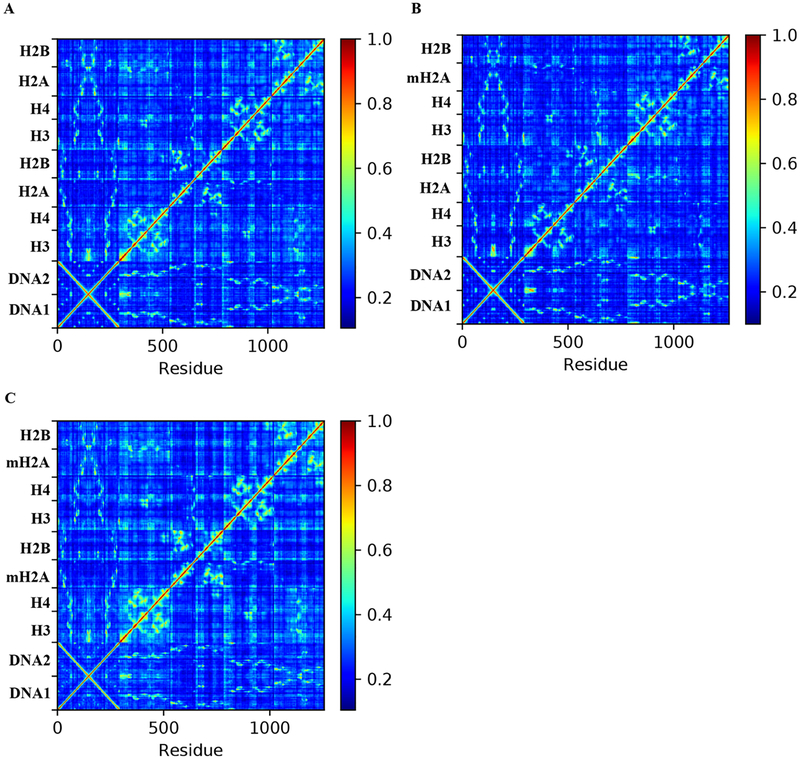

To probe the effects of the aforementioned unique dynamics on residue-pair correlations, we analyzed the generalized correlation matrix of both homogeneous systems and the hybrid H2A−macroH2A systems. We find that, on the whole, the residue-pair dynamics of the hybrid system are most similar to those of the canonical nucleosome (Figure 4). In contrast, the full substitution of macroH2A results in slightly elevated correlations across the molecule. Furthermore, we observe that the most important residues (“hot spots”) in the hybrid NCP allosteric networks more closely resemble the arrangement of hot spots within the canonical NCP construct than the macroH2A variant NCP, as measured by edge betweenness calculations (Figure 5). Using this metric, we previously identified that core post-translational modifications (PTMs) were enriched at allosteric hot spots in the nucleosome, and that PTM sites in the canonical complex were more prominently enriched than in variant NCPs. In contrast, the full substitution of H2A moieties with macro-H2A-like L1 loops redirected the allosteric networks of the NCP core, resulting in an increased centrality at the L1−L1 interface between H2A moieties. Together, these data indicate that addition of a single dimer is not sufficient to rearrange the allosteric networks of the core through the L1 interface, thereby invoking a different dynamic mechanism than that of total macroH2A substitution.

Figure 4.

Generalized correlation matrices for the (A) canonical, (B) hybrid, and (C) macroH2A NCPs. For each system, the average correlation matrix across all three separate simulations are shown. While the macroH2A NCP shows signs of strengthening between long-range residue-pair correlations, the hybrid NCP appears to be more canonical-like in the level of its correlation signal.

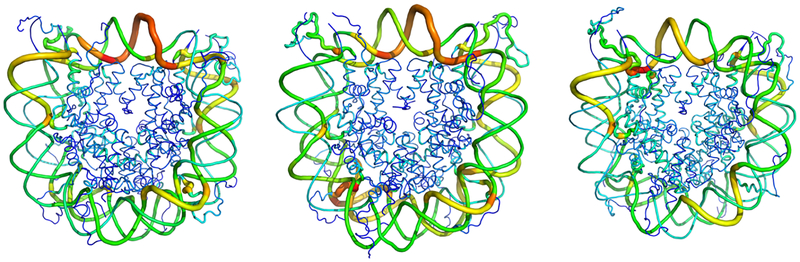

Figure 5.

Edge betweenness centrality values for residues in the hybrid (left), canonical (middle), and macroH2A (right) NCPs. Wider, brighter residues are allosteric hot spots and are therefore more essential for propagating dynamics throughout the systems. While the canonical and hybrid systems rely heavily upon the DNA, the α2 helix of the H2B moieties are also responsible for propagating dynamic correlations. In contrast, the macroH2A NCP relies less upon the DNA and H2B α2 helix and exhibits more importance on the L1 loops and H2A α2 helix. Furthermore, the betweenness of the protein core as a whole is slightly elevated, showing that the fully substituted macroH2A system contains a stronger set of protein−core dynamics in comparison to canonical H2A-containing systems. Rendering for these plots was conducted in PyMol.

3.4. Hybrid NCPs are Energetically Favored Over Homogeneous Constructs.

We once again utilized MMGB/SA analysis to estimate how these changes in domain and local dynamics affect the free energies of DNA−octamer binding and NCP complex assembly. We find that DNA binding is highly favorable across all three constructs—ΔGbinding = −428.6 ± 5.6, −434.5 ± 7.9, and −462.7 ± 5.2 kcal/mol for the canonical, macroH2A, and hybrid NCPs, respectively. While these MM-GB/SA values are meant to be interpreted qualitatively rather than quantitatively, they indicate that the hybrid construct is significantly more favorable than any of the other three systems, with a ΔΔGbinding of −34.1 ± 7.6 kcal/mol when compared against the canonical NCP. Previously, we observed that full substitution of the H2A L1 loops with the macroH2A sequence had a favorable shift in binding strength, compared to the canonical NCP,27 largely as a result of direct L1−DNA interactions. While these dynamics are unobserved in the hybrid simulations (Section 3.1), the removal of negative charge from the L1 loop region, which resides near the DNA, yields a net beneficial effect on DNA binding in comparison to the canonical construct (ΔΔGL1−DNA = −2.3 ± 0.1). More drastic contributions to the improved DNA binding in the hybrid NCP comes from a more relaxed DNA structure than in the canonical NCP (ΔΔGDNA ≈ 21 kcal/mol). Of this 21 kcal/mol, ~10 kcal/mol comes from an improved electrostatic arrangement, and an additional 6 kcal/mol can be attributed to a more relaxed internal conformation, most notably in the angle term.

In addition to binding DNA more favorably, we also observe that the hybrid nucleosome forms a more stable NCP complex than either homogeneous system. Using another MM-GB/SA calculation, we find that the free energy benefit of complex assembly (ΔGassembly) for the hybrid NCP is −679.1 ± 6.3 kcal/mol. This is more stable than either the homogeneous canonical (ΔGassembly = −618.6 ± 5.8 kcal/mol) or macroH2A (ΔGassembly = −637.1 ± 7.9 kcal/mol) nucleosomes, as previously calculated.

As a measure of potential asymmetry in octamer assembly, we calculated the dimer−hexamer binding energies for each moiety in all three systems. We find that the dimers located in the same position as the macroH2A flank in the hybrid system (“dimer 2” in Table 2) consistently show a slighly weaker binding strength, which might suggest a slight asymmetry in NCP dynamics regardless of histone content. Alternatively, this may also be a sign of allosteric effects resulting from the asymmetric initial coordinates and sampling of the histone tails. However, we once again find that the hybrid NCP dimers are most stably bound at either location (ΔGdimer 1 = −115.3 ± 0.4 kcal/mol and ΔGdimer 2 = −104.4 ± 0.4 kcal/mol). Moreover, comparisons between the macroH2A and canonical NCPs show that the macroH2A dimers are more stably bound to the hexamer complex (ΔGdimer 1 = −106.6 ± 2.5 kcal/mol and ΔGdimer 2 = −101.1 ± 3.0 kcal/mol in the canonical NCP; ΔGdimer 1 = −104.0 ± 3.1 kcal/mol and ΔGdimer 2 = −100.9 ± 3.7 kcal/mol in the macroH2A NCP), but the canonical dimer of the hybrid construct is actually more stable than the macroH2A moeity. Since the macroH2A dimer of the hybrid binds with a strength that is comparable to the homogeneous complex, these data show that it is the canonical portion of the hybrid construct that experiences the largest shift in binding favorability from a single macroH2A dimer substitution and not the macroH2A dimer itself. These data are consistent with the aforementioned dimer−tetramer and dimer−dimer contact analysis (Section 3.2, Table 1).

4. DISCUSSION

Using molecular dynamics simulations and analyses, we presented several structural and dynamics properties of hybrid macroH2A−H2A nucleosomes and how these complexes may behave differently from homogeneous constructs. The hybrid NCP was observed to most stably bind the 147 base pairs of DNA, and unique dynamics in the L1−L1 interface yielded stronger dimer−dimer interactions, contributing directly to a more favorable nucleosome complex assembly energy. Moreover, the dimer moieties in the hybrid system are drawn further into the center of the complex, which results in the stabilization of additional contacts between the canonical dimer and the histone tetramer and yielded a binding strength between the dimer and tetramer that was more favorable than that observed in the homogeneous canonical NCP. While the hybrid nucleosome also displayed some dynamics and structure that appeared to be a subsampling of either canonical- or macroH2A-like states, a slight propensity toward macroH2A-like values is observed.

The analyses presented here provide biophysical insight to previous biochemical studies on hybrid complex formation. For instance, Chakravarthy and Luger observed that, in the presence of both canonical H2A and macroH2A histone folds, hybrid nucleosomes were preferentially formed in vitro.24 Indeed, we also observe in our simulations that the hybrid NCP complex is the most energetically stable of each of the three complexes, as our MM-GB/SA analyses show that hybrid NCPs both bind DNA more strongly and form a more favorable total complex in comparison to either homogeneous system, and we find that this results from both DNA−protein and protein−protein interactions. Furthermore, while Chakravarthy and Luger observed that the hybrid NCPs in the crystal lattice preferentially formed with the macroH2A−H2B dimer on the same side, our Kullback−Leibler divergence analysis suggests that the dynamic behavior of individual residues within the substituted dimer differ similarly from either side of the molecule. These data suggest that, in solution, the hybrid NCP likely has no preference for replacing the entry- or exit-moiety and that the previously observed preference may be the effect of crystal packing forces. Our simulations also provide further support that the preferential formation of hybrid NCPs is energetically robust.

The presence of a hybrid histone core may be beneficial to higher-order chromatin compaction. That is to say, if the energetic preference for the NCP core was to have a full substitution of both H2A dimers with full-length macroH2A moieties, then that might introduce a steric penalty to compaction, as the linker segments and macro domains of both dimers would need to be accommodated. Instead, since we observe an energetic benefit for the hybrid H2A− macroH2A core, only a single linker segment and macro domain would be accounted for, and a more modest steric penalty may be introduced. In this case, the ability of the variant to inhibit poly-ADP ribosylation by PARP1 would likely be affected by the stoichiometry of present macro domains, as well as their species.23,25,51

Luger and Chakravarthy also observed that macroH2A and hybrid constructs, to a lesser extent, were resistant to exchange of dimers with the nucleosome assembly protein 1 (NAP1). In isolation of this information, our energetic analysis would suggest that the hybrid NCP should be the most resistant to this exchange, as the complex is the most stable. We believe that this discrepancy can be rectified by considering the selectivity of the NAP1 chaperone for particular histones.52 If NAP1 binds macroH2A dimers weaker than dimers containing canonical H2A, then a histone octamer containing only macroH2A dimers would be more resistant to dimer exchange than a canonical octamer. Here, we observe that the hybrid octamer possesses more favorable protein−protein interactions than the canonical protein fold, especially in terms of interactions between the canonical H2A dimer moiety and the remaining hexamer. This substantial dimer−hexamer stabilization would result in a reduced NAP1-mediated rate of exchange of this moiety in the hybrid construct, but the lack of the preferred interaction between NAP1 and the canonical H2A−H2B dimer would still result in the weakest amount of exchange occurring in the homogeneous macroH2A system. Since our energetic analysis suggested that the macroH2A dimer in the hybrid system is equally stable to the homogeneous macroH2A substitution, exchange measurements with a macroH2A-associated chaperone might provide interesting clarification on whether the hybrid substitution serves to only stabilize the canonical H2A moiety or if both moieties are truly benefited.

Our allosteric analyses suggest that nucleosome chemistry may also serve to modulate chromatin dynamics in the cell by altering long-range allosteric networks in the core particle.27 Recently, a study by Adhireksan et al. combined biochemical experiments with MD models to show that drug−drug allosteric synergy is possible in nucleosome-binding ligands targeted toward killing cancerous cells.53 In that work, the presence of the RAPTA-T molecule was shown to both increase the uptake of AUF to cells as well as reduce cell viability, and their MD results demonstrate that the rationale for this synergy is largely a result of RAPTA-T binding altering the structure and dynamics of the H2A α2 helix and its interactions with surrounding histone α-helices. In our modeling of single NCP allosteric hot spots, we find two of these helices—H2A α2 and H2B α2—are enriched with allosteric hot spots within the protein core, highlighting them as important to propagating dynamics throughout the histone octamer. As such, our models agree with the work of Adhireksan and colleagues in that altering the dynamics of these helices could be a promising target for potential epigenetic therapies.

Lastly, Engeholm et al. previously observed that sliding nucleosomes can invade the territory of neighboring constructs, resulting in an overlap of ~50 bp of DNA between them.54 To accomplish this, a single dimer of the NCP must be lost to accommodate the overlap, and a crystal structure of such an arrangement has been recently confirmed.55 The asymmetry in our dimer−hexamer energetic analyses suggest that, in the presence of such overlapping dinucleosomes, removal of a particular dimer could potentially be preferred, but more rigorous analyses should be conducted to determine the role of the initial conformation on our energetics results. Moreover, the asymmetry in dimer−hexamer binding suggests that kick-out of dimer may be preferential by species, as well, but the presence of the highly cationic linker segment may shift the favorability of retaining the macroH2A species over the canonical H2A, in contrast to our histone fold-only energetic analyses.

Overall, our study points to the fact that hybrid macroH2A nucleosome constructs have unique thermodynamic, dynamic, and structural properties. There is strong evidence for the presence of hybrid NCPs in vivo,56 as well as support for their potential role in regulating chromatin structure and transcription. It is altogether possible that asymmetric substitutions of other histone variants may also result in unique effects in comparison to their full substitution, potentially adding to an already growing field of evidence for asymmetric effects of nucleosome composition on its behavior.57–59 In the future, we believe that simulations and experiments aiming to understand the molecular basis of epigenetic regulation should consider these hybrid structures as unique moieties and not functioning as merely subcases of the symmetric canonical or modified nucleosomes.

5. CONCLUSION

In this study, we have performed conventional all-atom simulations on the hybrid nucleosome, containing one moiety of canonical H2A and one moiety of the macroH2A histone fold. The present simulations were compared against our previous models of the homogeneous H2A and macroH2A constructs,27 and we found that the dynamics of the hybrid structure sampled partially canonical-like and partially macro-H2A-like distributions. Particularly, the hybrid NCP showed unique dynamics at the L1−L1 interface, which resulted in significantly increased direct protein−protein interaction energies, as well as long-range, allosteric increases in DNA-binding energies. In the context of previous experimental studies, our MD models provide further evidence for the presence of hybrid NCP formation in chromatin and their associated role in transcriptional modulation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health [Grant Nos. R15GM114758 and R35GM119647]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work used the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment, which is supported by the National Science Foundation Grant No. ACI-1053575.60

Biography

Prof. Jeff Wereszczynski received his doctorate in Biophysics from the University of Michigan in 2008. Following this, he performed postdoctoral work at the University of California San Diego under the guidance of Prof. J. Andrew McCammon. He has been on the faculty of Illinois Institute of Technology as an Assistant Professor of Physics since 2013. His group’s research interests include using simulations to determine the molecular bases of epigenetic regulation, the mechanisms of bacteria virulence pathways, and developing methods to interpret simulation results in conjunction with experimental data.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.8b10668.

Evaluation of statistical significance for Kullback−Leibler divergence and three figures—RMSD timeseries, graphical representation of contact data from Table 1, and comparison histogram of hybrid dimer betweenness scores (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Published as part of The Journal of Physical Chemistry virtual special issue “Young Scientists”.

REFERENCES

- (1).Kornberg RD; Thomas JO Chromatin structure; oligomers of the histones. Science 1974, 184, 865–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Finch JT; Lutter LC; Rhodes D; Brown RS; Rushton B; Levitt M; Klug A Structure of nucleosome core particles of chromatin. Nature 1977, 269, 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Cutter AR; Hayes JJ A brief review of nucleosome structure. FEBS Lett. 2015, 589, 2914–2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Luger K; Mader AW; Richmond RK; Sargent DF; Richmond TJ Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature 1997, 389, 251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Chakravarthy S; Gundimella SK; Caron C; Perche PY; Pehrson JR; Khochbin S; Luger K Structural characterization of the histone variant macroH2A. Mol. Cell. Biol 2005, 25, 7616–7624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Davey CA; Sargent DF; Luger K; Maeder AW; Richmond TJ Solvent mediated interactions in the structure of the nucleosome core particle at 1.9 a resolution. J. Mol. Biol 2002, 319, 1097–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Bowman GD; Poirier MG Post-translational modifications of histones that influence nucleosome dynamics. Chem. Rev 2015, 115, 2274–2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Talbert PB; Henikoff S Histone variants−ancient wrap artists of the epigenome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2010, 11, 264–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Talbert PB; Henikoff S Histone variants on the move: substrates for chromatin dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2017, 18, 115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Bonisch C; Hake SB Histone H2A variants in nucleosomes and chromatin: more or less stable? Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 10719–10741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Berger SL The complex language of chromatin regulation during transcription. Nature 2007, 447, 407–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Musselman CA; Lalonde ME; Cote J; Kutateladze TG Perceiving the epigenetic landscape through histone readers. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2012, 19, 1218–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Nusinow DA; Sharp JA; Morris A; Salas S; Plath K; Panning B The histone domain of macroH2A1 contains several dispersed elements that are each sufficient to direct enrichment on the inactive X chromosome. J. Mol. Biol 2007, 371, 11–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Subramanian V; Fields PA; Boyer LA H2A.Z: a molecular rheostat for transcriptional control. F1000Prime Rep. 2015, 7, 01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Gaspar-Maia A; Qadeer ZA; Hasson D; Ratnakumar K; Leu NA; Leroy G; Liu S; Costanzi C; Valle-Garcia D; Schaniel C; et al. MacroH2A histone variants act as a barrier upon reprogramming towards pluripotency. Nat. Commun 2013, 4, 1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Weber CM; Henikoff S Histone variants: dynamic punctuation in transcription. Genes Dev. 2014, 28, 672–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Sansoni V; Casas-Delucchi CS; Rajan M; Schmidt A; Bonisch C; Thomae AW; Staege MS; Hake SB; Cardoso MC; Imhof A The histone variant H2A.Bbd is enriched at sites of DNA synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 6405–6420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Pehrson JR; Fried VA MacroH2A, a core histone containing a large nonhistone region. Science 1992, 257, 1398–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Chakravarthy S; Patel A; Bowman GD The basic linker of macroH2A stabilizes DNA at the entry/exit site of the nucleosome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 8285–8295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Abbott DW; Laszczak M; Lewis JD; Su H; Moore SC; Hills M; Dimitrov S; Ausio J Structural characterization of macroH2A containing chromatin. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 1352–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Abbott DW; Chadwick BP; Thambirajah AA; Ausio J Beyond the Xi: macroH2A chromatin distribution and post-translational modification in an avian system. J. Biol. Chem 2005, 280, 16437–16445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Muthurajan UM; McBryant SJ; Lu X; Hansen JC; Luger K The linker region of macroH2A promotes self-association of nucleosomal arrays. J. Biol. Chem 2011, 286, 23852–23864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Kozlowski M; Corujo D; Hothorn M; Guberovic I; Mandemaker IK; Blessing C; Sporn J; Gutierrez-Triana A; Smith R; Portmann T MacroH2A histone variants limit chromatin plasticity through two distinct mechanisms. EMBO Rep. 2018, 19, e44445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Chakravarthy S; Luger K The histone variant macro-H2A preferentially forms “hybrid nucleosomes. J. Biol. Chem 2006, 281, 25522–25531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Corujo D; Buschbeck M Post-translational modifications of H2A histone variants and their role inm cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Cantarino N; Douet J; Buschbeck M MacroH2A−an epigenetic regulator of cancer. Cancer Lett. 2013, 336, 247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Bowerman S; Wereszczynski J Effects of macroH2A and H2A.Z on nucleosome dynamics as elucidated by molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys. J 2016, 110, 327–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Jorgensen WL; Chandrasekhar J; Madura JD; Impey RW; Klein ML Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys 1983, 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Maier JA; Martinez C; Kasavajhala K; Wickstrom L; Hauser KE; Simmerling C ff14SB: improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2015, 11, 3696–3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Joung IS; Cheatham TE Determination of alkali and halide monovalent ion parameters for use in explicitly solvated biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 9020–9041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Joung IS; Cheatham TE Molecular dynamics simulations of the dynamic and energetic properties of alkali and halide ions using water-model-specific ion parameters. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 13279–13290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Phillips JC; Braun R; Wang W; Gumbart J; Tajkhorshid E; Villa E; Chipot C; Skeel RD; Kale L; Schulten K Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem 2005, 26, 1781–1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Grest GS; Kremer K Molecular dynamics simulation for polymers in the presence of a heat bath. Phys. Rev. A: At., Mol., Opt. Phys 1986, 33, 3628–3631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Martyna GJ; Tobias DJ; Klein ML Constant pressure molecular dynamics algorithms. J. Chem. Phys 1994, 101, 4177–4189. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Feller SE; Zhang Y; Pastor RW; Brooks BR Constant pressure molecular dynamics simulation: The Langevin piston method. J. Chem. Phys 1995, 103, 4613–4621. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Andersen HC Rattle: A “velocity” version of the shake algorithm for molecular dynamics calculations. J. Comput. Phys 1983, 52, 24–34. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Darden T; York D; Pedersen L Particle mesh Ewald: An Nlog(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys 1993, 98, 10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Essmann U; Perera L; Berkowitz ML; Darden T; Lee H; Pedersen LG A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys 1995, 103, 8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Humphrey W; Dalke A; Schulten K VMD − Visual Molecular Dynamics. J. Mol. Graphics 1996, 14, 33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.7.0.0; Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Roe DR; Cheatham TE PTRAJ and CPPTRAJ: software for processing and analysis of molecular dynamics trajectory data. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2013, 9, 3084–3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Miller BR; McGee TD; Swails JM; Homeyer N; Gohlke H; Roitberg AE MMPBSA.py: an efficient program for end-state free energy calculations. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2012, 8, 3314–3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Morrison EA; Bowerman S; Sylvers KL; Wereszczynski J; Musselman CA The conformation of the histone H3 tail inhibits association of the BPTF PHD finger with the nucleosome. eLife 2018, 7 DOI: 10.7554/eLife.31481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Ikebe J; Sakuraba S; Kono H H3 histone tail conformation within the nucleosome and the impact of K14 acetylation studied using enhanced sampling simulation. PLoS Comput. Biol 2016, 12, No. e1004788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Winogradoff D; Echeverria I; Potoyan DA; Papoian GA The acetylation landscape of the H4 histone tail: disentangling the interplay between the specific and cumulative effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 6245–6253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).McClendon CL; Hua L; Barreiro A; Jacobson MP Comparing conformational ensembles using the Kullback-Leibler divergence expansion. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2012, 8, 2115–2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Lange OF; Grubmuller H Generalized correlation for biomolecular dynamics. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Genet 2006, 62, 1053–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Brandes U A faster algorithm for betweenness centrality. J. Math. Sociol 2001, 25, 163–177. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Bowerman S; Wereszczynski J Detecting allosteric networks using molecular dynamics simulation. Methods Enzymol. 2016, 578, 429–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Altman DG; Bland JM How to obtain the P value from a confidence interval. Br. Med. J 2011, 343, d2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Nusinow DA; Hernandez-Munoz I; Fazzio TG; Shah GM; Kraus WL; Panning B Poly(ADPribose) polymerase 1 is inhibited by a histone H2A variant, MacroH2A, and contributes to silencing of the inactive X chromosome. J. Biol. Chem 2007, 282, 12851–12859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Mattiroli F; D’Arcy S; Luger K The right place at the right time: chaperoning core histone variants. EMBO Rep. 2015, 16, 1454–1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Adhireksan Z; Palermo G; Riedel T; Ma Z; Muhammad R; Rothlisberger U; Dyson PJ; Davey CA Allosteric cross-talk in chromatin can mediate drug-drug synergy. Nat. Commun 2017, 8, 14860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Engeholm M; de Jager M; Flaus A; Brenk R; van Noort J; Owen-Hughes T Nucleosomes can invade DNA territories occupied by their neighbors. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2009, 16, 151–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Kato D; Osakabe A; Arimura Y; Mizukami Y; Horikoshi N; Saikusa K; Akashi S; Nishimura Y; Park SY; Nogami J; et al. Crystal structure of the overlapping dinucleosome composed of hexasome and octasome. Science 2017, 356, 205–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Chakravarthy S; Bao Y; Roberts VA; Tremethick D; Luger K Structural characterization of histone H2A variants. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol 2004, 69, 227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Voigt P; LeRoy G; Drury WJ; Zee BM; Son J; Beck DB; Young NL; Garcia BA; Reinberg D Asymmetrically modified nucleosomes. Cell 2012, 151, 181–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Chen Y; Tokuda JM; Topping T; Meisburger SP; Pabit SA; Gloss LM; Pollack L Asymmetric unwrapping of nucleosomal DNA propagates asymmetric opening and dissociation of the histone core. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2017, 114, 334–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Ngo TT; Zhang Q; Zhou R; Yodh JG; Ha T Asymmetric unwrapping of nucleosomes under tension directed by DNA local flexibility. Cell 2015, 160, 1135–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Towns J; Cockerill T; Dahan M; Foster I; Gaither K; Grimshaw A; Hazlewood V; Lathrop S; Lifka D; Peterson GD; et al. XSEDE: Accelerating Scientific Discovery. Comput. Sci. Eng 2014, 16, 62–74. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.