Abstract

This study evaluated the Problem Behavior Frequency Scale – Adolescent Report (PBFS- AR), a measure designed to assess adolescents’ frequency of victimization, aggression, substance use, and delinquent behavior. Participants were 1,263 students (50% female; 78% African American, 18% Latino) from three urban middle schools in the United States. Confirmatory factor analyses of competing models of the structure of the PBFS-AR supported a model that differentiated among three forms of aggression (in-person physical, in-person relational, and cyber), two forms of victimization (in-person and cyber), substance use, and delinquent behavior. This seven-factor model fit the data well and demonstrated strong measurement invariance across groups that differed on sex and grade. Support was found for concurrent validity of the PBFS-AR based on its pattern of relations with school office discipline referrals.

Keywords: Aggression, Victimization, Cyber Aggression and Victimization, Problem Behaviors, School Office Referrals, Adolescence, Measurement Invariance

Researchers have used a variety of approaches to assess adolescents’ frequency of victimization, aggression, and other problem behaviors. These have included self-report, parent ratings, teacher ratings, archival data such as school office discipline referrals, and direct observations (e.g., Dahlberg, Toal, Swahn, & Behrens, 2005). Studies examining relations across different methods of assessing these constructs have generally found low to moderate agreement (e.g., Youngstrom, Loeber, & Stouthamer-Loeber, 2000). This may reflect the different sources of bias inherent in each approach (e.g., self-report, rater biases, reactivity of observational measures), and differences in the context of observation. For example, whereas adolescent-report measures typically assess behavior and experiences across multiple contexts, ratings by teachers and office discipline referrals are limited to behavior in school settings in situations where teachers and school staff observe students. In light of these differences, it is unlikely that any single approach can provide a complete picture of adolescents’ behavior. This highlights the need for well-developed measures to capture each of these perspectives (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005). This is particularly true for self-report measures, as they represent the most commonly used method to assess adolescents’ aggression and victimization experiences (Furlong, Sharkey, Felix, Tanigawa, & Green, 2010). There is also a need for measures that adequately assess multiple forms of problem behavior and victimization. The goal of this study was to evaluate a self-report measure designed to assess middle school students’ victimization experiences and their frequency of engaging in aggression, substance use, and other forms of delinquent behavior by examining its structure and its relation to school office discipline referrals.

A key issue in the study of both aggression and victimization is their underlying structure and their relations to other forms of problem behavior. Early studies viewed aggression as part of a broad constellation of adolescents’ problem behaviors and developed broad measures of problem behavior or externalizing behavior (cf. Jessor, 2014). More recently, researchers have viewed aggression as a distinct construct (e.g., Farrell, Kung, White, & Valois, 2000). This has led to the development of measures that assess specific forms of aggression and victimization (Card, Stucky, Sawalani, & Little, 2008). Although there is some consensus that aggression is a multi-dimensional construct, there is less agreement about its underlying structure. For example, some researchers have differentiated between direct forms that encompass physical (e.g., hitting, or attacking with a weapon) and verbal acts (e.g., name-calling) versus indirect forms such as spreading rumors or gossip that do not involve directly confronting the victim (e.g., Card et al., 2008). Others (e.g., Galen & Underwood, 1997) have drawn a distinction based on the intent of the aggressor. Within this framework physical aggression represents acts or threats that result in physical harm or injury. This differs from social or relational aggression, which represent acts intended to harm the victim’s relationships or social status.

This raises interesting questions about the relation between specific forms of aggression and externalizing behaviors such as conduct problems, delinquent behavior and substance use. Whereas physical aggression is considered a form of externalizing behavior, non-physical acts such as verbal aggression and relational aggression might be considered more normative and may consequently be less strongly related to externalizing behaviors. This is supported by Farrell et al. (2016) who found that compared with relational and verbal aggression, adolescent ratings of their frequency of physical aggression were more highly correlated with teacher ratings of conduct problems, and with adolescent reports of their substance use and delinquent behavior. A meta-analysis by Card et al., (2008) also found stronger relations with both self-report and teacher ratings of delinquency and conduct problems for direct aggression (i.e., physical and verbal) than for relational aggression. This highlights the importance of determining where specific forms of aggression fit within the context of externalizing or problem behavior.

Researchers have similarly failed to reach a consensus regarding the structure of victimization. Some studies have found support for differentiating among multiple forms of victimization experienced by adolescents (e.g., Bradshaw, Waasdorp, & Johnson, 2015). Others have found that form may be less important than frequency (Nylund, Bellmore, Nishina, & Graham, 2007). Perhaps the least consistency has been in the treatment of verbal forms of victimization such as teasing and name-calling. Some studies have found support for combining verbal and physical victimization into an Overt Victimization factor (e.g., Farrell, Sullivan, Goncy & Le, 2016; Rosen, Beron, & Underwood, 2013). Others have found support for combining verbal and relational victimization into a Nonphysical Victimization factor (e.g., Hunt, Peters, & Rapee, 2012). Still others have regarded verbal victimization as a distinct construct (Marsh et al., 2011). Determining the structure of aggression and victimization, establishing their relations to substance use and other forms of delinquent behavior, and developing measures that best reflect this structure is critical to advancing theory and guiding future research.

The need for better measures of aggression and victimization that are consistent with current theories is particularly evident in the burgeoning research on cyber aggression and victimization (Mehari, Farrell, & Le, 2014). There are major limitations with current measures of cyber aggression (also called cyberbullying) and cyber victimization. Most research has measured cyber aggression and victimization as constructs distinct from in-person aggression and victimization (for a review and meta-analysis see Kowalski, Giumetti, Schroeder, & Lattanner, 2014). Much of this work is based on the underlying assumption that aggression and victimization experiences via electronic communication technologies are qualitatively different from those that occur in-person (Mehari et al., 2014; Tokunaga, 2010). However, few studies have empirically evaluated this assumption by testing competing models of in-person and cyber aggression and victimization (see Landoll, La Greca, Lai, Chan, & Herge, 2015; and Mehari & Farrell, 2018 for exceptions). Moreover, much of the prior research has relied on single-item measures or on multi-item measures that ask about the type of media (e.g., text messages or emails, cell phones or computers), but do not address the specific behaviors (e.g., posting embarrassing pictures, excluding another adolescent; Salmivalli, Sainio, & Hodges, 2013; Wang, Iannotti, & Nansel, 2009). These measures do not address the need for measures of cyber aggression and victimization that are as comprehensive as those assessing in-person victimization (Menesini, 2012).

The Problem Behavior Frequency Scale – Adolescent Report (PBFS-AR)

The Problem Behavior Frequency Scale-Adolescent Report form (PBFS-AR; Farrell et al., 2016) is a self-report measure designed to assess adolescents’ frequency of victimization, aggression and other problem behaviors. The PBFS-AR has several advantages over other self-report measures of adolescents’ aggression and victimization. It addresses multiple forms of both in-person and cyber aggression and victimization (i.e., physical, verbal, and relational), substance use, and delinquent behavior. This provides a basis for examining the relations among these constructs and assessing multiple outcomes. It specifies the time frame (i.e., past 30 days) using an operationally-defined 6-point frequency scale (e.g., Never, 1–2 times, 3–5 times), which provides a clear basis for assessing change over time. It also focuses on specific behaviors, which may be more clearly interpreted than items that assess intent (e.g., “When someone hurts me, I end up getting into a fight,” “I am deliberately cruel to others, even if they haven’t done anything to me”; Marsee et al., 2011) or general dispositions (e.g., “I am the kind of person who often fights with others”; Little et al., 2003).

Farrell et al. (2016) evaluated an earlier version of the PBFS-AR that did not include items assessing cyber aggression or victimization using data from 5,532 adolescents from 37 schools in four states. Their confirmatory factor analyses of competing models found support for seven factors. These represented three forms of aggression (physical, verbal, and relational), two forms of victimization (overt and relational), substance use, and other delinquent behavior. They also found evidence of strong measurement invariance (i.e., scalar invariance) such that the structure, factor loadings, and thresholds of items did not differ across sex, geographic locations, or grades. Their analyses of correlations among the seven factors provided clearer evidence for representing physical and relational aggression as distinct factors (r = .74) than for verbal aggression, which was highly correlated with the Physical Aggression and Relational Aggression factors (rs = .89 and .82, respectively).

Farrell et al. (2016) evaluated the concurrent validity of the PBFS-AR based on its correlations with teacher ratings on the Behavioral Assessment System for Children (BASC-2; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004) and with adolescent reports on measures of other relevant constructs. The PBFS-AR Physical Aggression, Delinquent Behavior, and Substance Use factors were positively correlated with teachers’ ratings on the BASC Aggression (rs = .20 to .24) and Conduct Problems (rs = .23 to .26) scales and were negatively correlated with the BASC Adaptive Behavior scale (rs = −.26 to −.22). Whereas the PBFS-AR Verbal Aggression factor was also significantly correlated with the BASC Aggression scale (r = .24), it was not as strongly related to the BASC Conduct Problems or Adaptive Behavior scales. These correlations were all smaller for the PBFS-AR Relational Aggression factor (rs = .14 to .16 in absolute value). As predicted, the PBFS-AR Overt Victimization and Relational Victimization factors had small, but significant correlations with the BASC Depression scale (rs = .12 and .17, respectively). Scales on the PBFS-AR also showed the expected pattern of correlations with adolescent reports on measures of related constructs. The PBFS-AR Physical Aggression, Delinquent Behavior, and Substance Use factors were positively correlated with delinquent peer associations (rs = .48 to .50), and with measures of norms and beliefs supporting aggression (rs = .32 to .47). These correlations were generally smaller for the PBFS-AR Relational Aggression (rs = .30 to .41) and Verbal Aggression factors (rs = .32 to .42). Correlations for the two PBFS-AR victimization factors were considerably lower (rs = −.05 to .28).

The Present Study

The present study evaluated a revised version of the PBFS-AR (Version 2) administered to a large, predominantly African American sample of middle school students. Revisions included adding some additional items to assess in-person verbal aggression, in-person physical victimization, and in-person verbal victimization, and substance use. A major revision was expanding the measure to include items representing cyber forms of both aggression and victimization. This study had several objectives. The first was to compare competing models of the structure of victimization, aggression, and other problem behaviors based on this expanded pool of items. We hypothesized that support would be found for factors representing specific forms of aggression and victimization, and factors representing substance use and delinquent behavior. Based on the Farrell et al. (2016) study we expected to find support for factors representing physical, verbal, and relational forms of in-person aggression. Although Farrell et al. found support for two victimization factors (overt and relational), their study included only one item representing verbal victimization. We anticipated that our inclusion of additional verbal victimization items would result in three distinct in-person victimization factors (physical, verbal, and relational). We further hypothesized that cyber and in-person forms of both aggression and victimization would represent distinct factors based on previous studies and on the qualitative differences between interactions via electronic communication technologies and in person interactions (Landoll et al., 2015; Mehari et al., 2014; Mehari & Farrell, 2018). However, we were less certain whether cyber aggression and victimization items would be best represented by single aggression and victimization factors, or by factors that paralleled their in-person counterparts (i.e., physical, verbal and relational forms of cyber aggression and victimization).

A second objective was to test for measurement invariance. There has been increasing recognition of the need to establish measurement invariance, or the degree to which measurement properties are consistent across individuals, contexts, and over time (Rosen et al., 2013). Despite its importance, few attempts have been made to evaluate the measurement invariance of measures assessing constructs such as aggression, victimization and problem behaviors (e.g., Farrell et al., 2016; Marsee et al., 2011; Queirós & Vagos, 2016; Rosen et al., 2013). Based on analyses of the earlier version of the PBFS-AR by Farrell et al. (2016), we hypothesized that there would be strong measurement invariance across sex and grade.

Finally, we evaluated the concurrent validity of the PBFS-AR by examining its relation to school office discipline referrals. Prior work has supported the use of school office discipline referrals to validate teacher and parent report measures of student behavior (for a review, see McIntosh, Fisher, Kennedy, Craft, & Morrison, 2012). We hypothesized that students who had office discipline referrals for physical aggression would have higher scores on the PBFS-AR Physical Aggression factor than those without such referrals, and that students with office discipline referrals for disruptive behavior and those with out-of-school suspensions would have higher scores on each of the problem behavior factors compared with those that did not. We did not expect to find relations between office discipline referrals and suspensions and victimization factors.

Method

Participants and Setting

We conducted secondary analysis of data from students at three middle schools in the southeastern United States who participated in a project (Farrell, Sullivan, Sutherland, Corona, & Masho, 2018) that evaluated the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (e.g., Olweus & Limber, 2010). The majority of students in these schools (i.e., 74% to 85%) were eligible for the federal free lunch program. Participants were recruited from a random sample of students from each school’s roster. Parental consent and student assent were obtained from 80% of those eligible. Participants continued in the study until they left the school or chose to discontinue participation. Each year a new sample of entering sixth graders was recruited, and seventh and eighth graders were recruited to replace students who left the study. The project collected data every 3 months using a planned missing-data design (Graham, Taylor, & Cumsille, 2001) such that each student was randomly assigned to complete measures at two waves each year to reduce participant fatigue and testing effects. The study was approved by the IRB of the authors’ university.

We conducted our analyses on 3,261 observations collected from the 1,263 students who completed measures at one or more waves during three years of the project (i.e., 2014 to 2017), during which this revised version of the PBFS-AR was administered. The Olweus intervention was implemented in two of the schools during the 2014–2015 school year and in all three schools during the following two school years. The sample was 50% female. Eighteen percent of participants identified themselves as Hispanic or Latino. The majority (78%) reported their race as African American or Black, including 9% who endorsed more than one race. Five percent described themselves as White. Thirteen percent described their race as Other, the majority of whom (90%) identified themselves as Hispanic or Latino. Regarding family structure, 38% lived with a single mother, 28% with both biological parents, and 20% with a parent and stepparent. Participants’ ages ranged from 10 to 16, with 96% of observations collected from students between 11 and 14 years old.

We obtained school records on office discipline referrals for the 2014–2015 and 2015–2016 school years for each participant. Because office referrals reflected behavior during the school year, we generated a separate dataset for analyses of office discipline referrals that included one wave of data for each participant randomly selected from the three waves collected during the school year. This provided a subsample of 957 students for analyses of relations with disciplinary data.

Measures

Problem Behavior Frequency Scale – Adolescent Report (PBFS-AR), Version 2.

We used a revised version of the PBFS-AR that expanded the content of the previous version of the scale (Farrell et al., 2016). Items on the previous version were based on prior research (e.g., Crick & Grotpeter, 1995), the Center for Disease Control’s Youth Risk Survey (Kolbe, Kann, & Collins, 1993), school observations, and focus groups on interpersonal problem situations. It included 14 items to assess in-person aggression (physical, verbal, and relational), 10 items to assess in-person victimization (overt and relational), 5 items to assess nonviolent delinquent behavior (i.e., illegal behaviors such as theft, shoplifting, vandalism), and 6 items to assess substance use (e.g., beer, wine, cigarettes, liquor, marijuana). Version 2 of the PBFS-AR includes 11 new items to assess cyber aggression and 11 new items to assess cyber victimization. These were based on a systematic review of existing measures of cyberbullying (Mehari et al., 2014) and qualitative studies investigating cyber aggression (e.g., Mishna, Saini, & Solomon, 2009). Our goal was to include items representing physical (e.g., “Used text messaging to threaten someone physically”), verbal (e.g., “Called someone you know mean names online like on Facebook or SnapChat, or through testing”), and relational (e.g., “posted rude comments about someone you know online”) acts of aggression that could be perpetrated or experienced using electronic communication technologies. In addition, we added items to expand the pool assessing in-person aggression, in-person victimization, nonviolent delinquent behavior, and substance use. We also revised the wording to make items represent behavior across multiple contexts (i.e., “stolen something from another student” was changed to “stolen something”). For a listing of all 73 items on the PBFS-AR and their prevalence rates (i.e., percentage endorsing more than Never) see Table S1.

Items assessing behavior were preceded by the stem: “In the last 30 days, how many times have you?” Victimization items were preceded by the stem: “In the last 30 days, how many times has this happened to you?” All items were rated on a 6-point frequency scale, 1 = Never, 2 = 1–2 times, 3 = 3–5 times, 4 = 6–9 times, 5 = 10–19 times, and 6 = 20 or more times. Participants completed the measure either in small groups at school during the school year or individually at home during the summer, using a computer-assisted interview.

School office discipline referrals.

We created two composites based on office discipline referrals obtained from school records (see Table 1). The physical aggression composite included physical fights, and assaults on students or staff. The disruptive behavior composite included disruptive behavior, defiance or insubordination, disrespect, and obscene or inappropriate language or literature. We created composites for each student based on office referrals during the school year they completed the PBFS-AR. Because the distribution of these variables was restricted (i.e., only a small percentage of participants had more than 1 or 2 incidents), we conducted analyses on binary variables reflecting the presence or absence of one or more office referrals within each of the categories. We also constructed a binary variable indicating the presence or absence of one or more out-of-school suspension during the school year.

Table 1.

Number and Percentage of Students With One or More Office Discipline Referral or Out-Of-School Suspension

| Referral Code | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Office referrals for physical aggression | ||

| Minor fighting altercation | 78 | 8.1% |

| Fighting with no injury or a minor injury | 41 | 4.2% |

| Assault and battery without a weapon on students | 18 | 1.9% |

| Assault and battery without a weapon on staff | 7 | 0.7% |

| Sexual offense involving touching against another student | 3 | 0.3% |

| Physical aggression composite | 133 | 13.8% |

| Office referrals for disruptive behavior | ||

| Disruptive demonstrations | 217 | 22.5% |

| Defiance/insubordination | 133 | 13.8% |

| Classroom or campus disruption | 87 | 9.0% |

| Disrespect | 46 | 4.8% |

| Obscene/inappropriate language | 45 | 4.7% |

| Minor insubordination | 10 | 1.0% |

| Obscene/disruptive literature | 3 | 0.3% |

| Disruptive behavior composite | 307 | 31.8% |

| Suspensions | ||

| Out-of-school suspension | 280 | 29.0% |

Note. N = 965. Includes only those codes for which at least one incident was reported during the school year.

Analysis

We used Mplus 8 to conduct confirmatory factor analysis of the structure of the PBFS-AR. Items were treated as ordered categorical variables using weighted least squares mean- and variance-adjusted estimators (WLSMV). This analysis is comparable to a graded response item-response theory model. Analyses were conducted on all 3,261 observations using sandwich estimators (i.e., Mplus type=complex option) to address non-independence resulting from multiple observations of each student (Muthén & Satorra, 1995). Although items were rated on a 6-point scale, very few participants (i.e., 1.2% or less) endorsed higher frequency categories. Such low frequencies create problems for the WLSMV estimator. Inspection of item characteristic curves based on an initial model suggested very little differentiation among the highest frequency categories. We therefore re-coded all items into four categories by combining the three highest categories.

We first conducted separate analyses of aggression and victimization items within each media (in-person and cyber). In separate analyses of in-person and cyber aggression, we compared: (a) three-factor models that differentiated among the three forms of aggression (physical, verbal, and relational); (b) two-factor models that differentiated between overt (i.e., physical and verbal) and relational aggression; (c) two-factor models that differentiated between physical and non-physical (i.e., verbal and relational) aggression; and (d) models specifying a single in-person or cyber aggression factor. These models formed the basis for further analyses to compare models that evaluated the extent to which in-person and cyber aggression items could be best represented by: (a) factors that emerged from the separate analyses of each type of media, (b) two-factor models defined by media (i.e., in-person versus cyber aggression), and a single overall aggression factor. We tested a similar series of models to evaluate the structure of the in-person and cyber victimization items. Finally, we incorporated the resulting in-person and cyber aggression and victimization factors into a full model that also included the substance use and delinquent behavior items.

We compared the fit of competing models based on the difference test provided by Mplus (see Asparouhov & Muthén, 2006), and evaluated overall model fit using Hu and Bentler’s (1999) recommendations as general guidelines. We considered models to have a good fit based on cutoffs of close to .95 or higher on the comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis fit index (TLI), and close to .06 or lower for the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). We conducted tests of measurement invariance on the final model across sex and grade. Because the large sample size provided power to detect minor differences in fit, we followed Cheung and Rensvold’s (2002) recommendations and did not favor more complex models unless they improved the CFI by more than .01.

Finally, we conducted analyses of covariance to examine the relation between scores on the PBFS-AR and office discipline referrals. Within these models, latent variables representing the PBFS-AR factors were regressed on dummy-coded variables representing the presence or absence of office discipline referrals for physical aggression, referrals for disruptive behavior, and in-school and out-of-school suspensions. Analyses controlled for sex, grade (dummy coded), and intervention condition, which we included as covariates.

Results

Structure of Aggression

In-person aggression.

A three-factor model with separate factors for physical, verbal and relational forms of in-person aggression fit the data very well. It also fit significantly better than the other three models (all ps < .001), and improved the fit based on the CFI by more than .01 for each of the models (see models 1–4 in Table 2), except for the two-factor model that combined physical and verbal aggression items into an Overt Aggression factor (ΔCFI = .004). Within the three-factor model, the Verbal Aggression factor was highly correlated with the Physical and Relational Aggression factors (rs = .97 and .88, respectively). Based on this finding we conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to provide additional information regarding the structure of in-person aggression, in particular where items representing verbal aggression best fit. The EFA suggested no more than two factors based on the eigenvalues (9.49, 1.37, 0.739, . . .), and the marginal improvement in fit for the three-factor EFA model over the two-factor EFA model (ΔCFI = .007). Review of a two-factor solution specifying an oblique rotation (i.e., geomin) indicated that all four physical aggression items had their highest loadings on Factor 1 (λs = .37 to 1.04), with only one cross-loading (i.e., λ > .30) on Factor 2 (see Table S2). All five relational aggression items had their highest loadings on Factor 2 (λs = .63 to .90), with no cross-loadings on Factor 1. In contrast, the six verbal aggression items did not consistently fit within this structure. Two items (i.e., “Yelled at someone or called them mean names” and “Put someone down to their face”) had high loadings on Factor 1 (i.e., λs = .70 to .80) with no cross-loadings on Factor 2. We considered incorporating these items into the Physical Aggression factor, but concluded that they did not represent the construct of physical aggression as captured by the other items in this factor, all of which represented clearly defined acts or threats of physical aggression. The other four verbal aggression items had cross-loadings on both factors (i.e., λs = .32 to .55). Although both the confirmatory and exploratory factor analyses supported separate factors for physical and relational aggression, items representing verbal forms of aggression did not clearly fit into this structure. Based on these findings, we removed the verbal in-person aggression items from all subsequent analyses. Analyses of the remaining items provided strong support for a two-factor model with separate factors representing physical and relational aggression (see Model 5 in Table 2). This two-factor model fit the data significantly better than a model specifying a single overall In-Person Aggression factor (see Model 6 in Table 2).

Table 2.

Fit Indices for Competing Models of the Factor Structure of the Problem Behavior Frequency Scale-Adolescent Report Aggression Items

| Model | χ2a | df | χΔ2b | dfΔb | RMSEA | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-person aggression models | |||||||

| 1. 3-factor (physical, verbal, and relational) | 617.47*** | 101 | .047 | .975 | .970 | ||

| 2. 2-factor combining verbal and physical | 701.07*** | 103 | 71.68*** | 2 | .042 | .971 | .966 |

| 3. 2-factor combining verbal and relational | 914.78*** | 103 | 159.62*** | 2 | .049 | .961 | .954 |

| 4. 1-factor | 997.88*** | 104 | 218.86*** | 3 | .051 | .957 | .950 |

| 5. 2-factor (physical and relational) excluding verbal items | 184.83*** | 34 | .037 | .984 | .978 | ||

| 6. 1-factor excluding verbal items | 546.03*** | 35 | 140.78*** | 1 | .067 | .944 | .928 |

| Cyber aggression models | |||||||

| 7. 3-factor (physical, verbal, and relational) | 110.39*** | 41 | .023 | .995 | .993 | ||

| 6. 2-factor combining verbal and physical | 125.78*** | 43 | 14.51*** | 2 | .024 | .994 | .992 |

| 9. 2-factor combining verbal and relational | 114.89*** | 43 | 6.04* | 2 | .023 | .994 | .993 |

| 10. 1-factor | 126.49*** | 44 | 16.97** | 3 | .024 | .994 | .992 |

| In-person and cyber aggression models (without verbal aggression items) | |||||||

| 11. 3-factor (in-person physical and relational, cyber aggression) | 606.55*** | 186 | .026 | .980 | .977 | ||

| 12. 2-factor defined by media (in-person, cyber) | 1032.92*** | 188 | 170.36*** | 2 | .037 | .959 | .954 |

| 13. 1-factor | 1332.30*** | 189 | 274.00*** | 3 | .043 | .945 | .938 |

Note. N = 3,216 observations from 1,263 participants. RMSEA= root mean-square error of approximation. CFI = comparative fit index. TLI = Tucker-Lewis fit index.

Chi-square test of model fit.

Chi-square difference test comparing fit of each model to the first model listed within each set (i.e., Models 1, 5, 7, and 11). Significant chi-square values indicate that the first model resulted in a significant improvement in fit.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Cyber aggression.

All four competing models of cyber aggression fit the data well (see Models 7–10 in Table 2). Although the three-factor model fit significantly better than the other three models (all ps < .001), it did not improve the fit based on the CFI by more than .01 compared with any of the other models, including the one-factor model. Loadings for the one-factor model were consistently high ranging from .88 to .92 for physical aggression items, .81 to .90 for verbal aggression items, and .70 to .90 for relational aggression items. This suggested that a single overall factor could adequately represent the 11 items encompassing different forms of cyber aggression.

Combined in-person and cyber aggression models.

Comparison of competing models of the structure of items representing both in-person and cyber forms of aggression favored a three-factor model that included the two in-person aggression factors (Physical Aggression and Relational Aggression) and the Cyber Aggression factor (see models 11–13 in Table 2). This model fit the data significantly better than a two-factor model defined by media (In-Person and Cyber Aggression) and a model specifying a single overall Aggression factor, and resulted in an improvement in model fit (ΔCFI = .011 and .017, respectively).

Structure of Victimization

All four models of victimization items fit the data well in separate analyses of in-person (see models 1 to 4 in Table 3) and cyber victimization (see models 5 to 8 in Table 3). For both in-person and cyber victimization, the three-factor model with separate factors for physical, verbal, and relational victimization fit significantly better than the other three models, but the improvement was modest even compared with the single-factor model (ΔCFI = .008 and .000 for in-person and cyber victimization models, respectively). Moreover, correlations among the three form factors were highly correlated within the in-person (rs = .91 to .95) and cyber victimization (rs = .97 to .99) models. This suggested that little was gained by differentiating among the three forms of victimization within each media.

Table 3.

Fit Indices for Competing Models of the Factor Structure of the Problem Behavior Frequency Scale-Adolescent Report Victimization Items

| Model | χ2a | df | χΔ 2b | dfΔb | RMSEA | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-person victimization models | |||||||

| 1. 3-factor (physical, verbal, and relational) | 583.17*** | 87 | .042 | .980 | .976 | ||

| 2. 2-factor combining verbal and physical | 612.47*** | 89 | 29.13*** | 2 | .043 | .979 | .975 |

| 3. 2-factor combining verbal and relational | 732.23*** | 89 | 92.71*** | 2 | .047 | .974 | .970 |

| 4. 1-factor | 768.14*** | 90 | 128.06*** | 3 | .048 | .972 | .968 |

| Cyber victimization models | |||||||

| 5. 3-factor (physical, verbal, and relational) | 313.62*** | 41 | .045 | .978 | .970 | ||

| 6. 2-factor combining verbal and physical | 307.49*** | 43 | 0.64 | 2 | .044 | .978 | .972 |

| 7. 2-factor combining verbal and relational | 314.68*** | 43 | 4.34 | 2 | .044 | .978 | .972 |

| 8. 1-factor | 310.89*** | 44 | 4.83 | 3 | .043 | .978 | .973 |

| In-person and cyber victimization models | |||||||

| 9. 3-factor by form (physical, verbal, and relational) | 2068.74*** | 296 | .043 | .945 | .939 | ||

| 10. 2-factor defined by media (in-person, cyber) | 1506.30*** | 298 | .035 | .962 | .959 | ||

| 11. 1-factor | 2170.85*** | 299 | 124.80*** | 3 | .044 | .942 | .937 |

Note. N = 3,216 observations from 1,263 participants. RMSEA= root mean-square error of approximation. CFI = comparative fit index. TLI = Tucker-Lewis fit index.

Chi-square test of model fit.

Chi-square difference test comparing fit of each model to the first model listed within each set (i.e., Models 1, 5, and 9). Significant chi-square values indicate that the first model resulted in a significant improvement in fit.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

We next conducted analyses of the full set of victimization items (i.e., both in-person and cyber) to compare a three-factor model defined by form of victimization (physical, verbal, and relational victimization), a two-factor model defined by media (in-person and cyber victimization), and a single-factor model (see models 9–11 in Table 3). Of these, the two-factor model defined by media had the best fit, increasing the CFI by .017 over the three-factor model, and .020 over the one-factor model. In other words, there was support for differentiation among victimization items based on the media (i.e., in-person and cyber), but not based on their form (i.e., physical, verbal, and relational).

Overall Structure of the PBFS-AR

We next examined the structure of the full set of PBFS-AR items. Based on the separate analyses of the aggression and victimization items, we excluded the verbal aggression items and tested a seven-factor model with factors representing in-person physical aggression, in-person relational aggression, cyber aggression, in-person victimization, cyber victimization, substance use, and nonviolent delinquent behavior. This seven-factor model fit the data very well in the overall sample (see Model 1 in Table 4). It also fit the data well in separate analyses by sex (RMSEAs = .017 and .018, CFIs = .95 and .98, TLIs = .95 and .97 for boys and girls, respectively), and by grade (RMSEAs = .014 to .020, CFIs = .96 to .98, TLIs = .96 to .98). All correlations among the seven factors in the analysis of the full sample were positive and significant (see Table 5). The three forms of aggression (in-person physical, in-person relational, and cyber) were highly correlated with each other (rs = .78 to .89) and with the Delinquent Behavior factor (rs = .77 to .83), and had lower correlations with the Substance Use factor (rs = .55 to .66). The In-Person and Cyber Victimization factors were also highly correlated with each other (r = .85), and with the In-Person Physical, In-Person Relational, and Cyber Aggression factors (rs = .58 to .80), Delinquent Behavior factor (rs = .58 and .66, respectively) and Substance Use factor (rs = .42 and .52, respectively). Standardized factor loadings for the seven-factor model based on the full sample ranged from .74 to .93 (see Table 6).

Table 4.

Fit Indices for Seven Factor Models of the Factor Structure of the Problem Behavior Frequency Scale-Adolescent Report

| Model | χ2a | df | χΔ2b | dfΔb | RMSEA | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full sample | |||||||

| 1. Overall model | 3888.99 | 1808 | .019 | .954 | .952 | ||

| Multiple group by sex | |||||||

| 2. Configural invariance | 5389.47*** | 3616 | .017 | .964 | .963 | ||

| 3. Scalar invariance | 5441.09*** | 3788 | 206.89* | 172 | .016 | .967 | .967 |

| Multiple group by grade | |||||||

| 4. Configural invariance | 7142.71*** | 5424 | .017 | .969 | .968 | ||

| 5. Scalar invariance | 7381.67*** | 5768 | 431.79*** | 344 | .016 | .971 | .972 |

Note. N = 3,216 observations from 1,263 participants. RMSEA= root mean-square error of approximation. CFI = comparative fit index. TLI = Tucker-Lewis fit index.

Chi-square test of model fit.

Chi-square difference test comparing fit of configural invariance and scalar invariance models.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 5.

Correlations and mean differences among factors in final seven-factor model for the Problem Behavior Frequency Scale – Adolescent Report

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. In-Person Physical Aggression | - | ||||||

| 2. In-Person Relational Aggression | .78*** | - | |||||

| 3. Cyber Aggression | .80*** | .89*** | - | ||||

| 4. Delinquent Behavior | .77*** | .80*** | .83*** | - | |||

| 5. Substance Use | .66*** | .55*** | .65*** | .80*** | - | ||

| 6. In-Person Victimization | .62*** | .72*** | .60*** | .58*** | .42*** | - | |

| 7. Cyber Victimization | .58*** | .71*** | .80*** | .66*** | .52*** | .85*** | - |

| d-coefficients | |||||||

| Boys v Girls | −0.16 | −0.21 | −0.22* | −0.19 | −0.07 | −0.21* | −0.44* |

| 7th grade v 6th grade | −0.17 | −0.31* | 0.00 | −0.35 | 0.17 | −0.35*** | 0.26 |

| 8th grade v 6th grade | −0.22* | −0.53*** | 0.00 | −0.42* | 0.27 | −0.45*** | 0.10 |

Note. N = 3,216 observations from 1,263 participants.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 6.

Standardized Loadings in Final Seven-Factor Confirmatory Factor Model

| Item | Factor Loading |

|---|---|

| In-Person Physical Aggression factor | |

| 10. Hit or slapped someone | .79 |

| 11. Thrown something at someone to hurt them | .78 |

| 15. Threatened to hit or physically harm someone | .88 |

| 18. Shoved or pushed someone | .81 |

| 30. Threatened someone with a weapon (gun, knife, club, etc.) | .85 |

| In-Person Relational Aggression | |

| 1. Told someone you wouldn’t like them unless they did what you wanted | .75 |

| 2. Spread a false rumor about someone | .75 |

| 5. Tried to keep others from liking another kid by saying mean things about him or her | .80 |

| 14. Left someone out on purpose when it was time to do an activity | .74 |

| 24. Not let someone be in your group anymore because you were mad at them | .81 |

| Cyber Aggression factor | |

| 9. Used text-messaging to threaten to hurt someone physically | .90 |

| 19. Used cell phone pictures to threaten to hurt someone physically | .92 |

| 4. Used cell phone pictures to make fun of someone | .79 |

| 13. Used a chat room or Internet website to make fun of someonea | .88 |

| 21. Used text-messaging to make fun of someone | .86 |

| 62. Called someone you know mean names online like on Facebook or SnapChat or through texting. | .81 |

| 63. Pretended to be someone else online or through texting. | .77 |

| 64. Left someone out of an online group or unfriended them on Facebook. | .78 |

| 65. Sent or posted embarrassing pictures of someone without their permission. | .82 |

| 66. Posted rude comments about someone you know online. | .85 |

| 67. Spread rumors about someone you know online or through textinga. | .92 |

| In-Person Victimization factor | |

| 42. Someone threatened to hit or physically harm youa | .74 |

| 46. Someone pushed or shoved you | .74 |

| 49. Someone threatened or injured you with a weapon (gun, knife, club, etc.)a | .82 |

| 59. Someone hit you hard enough to hurt | .79 |

| 51. Someone threw something at you to hurt you | .81 |

| 55. Someone yelled at you or called you mean names | .81 |

| 44. Someone put you down to your facea | .77 |

| 47. Someone said something disrespectful to you about your family | .79 |

| 52. Someone teased you to make you mad | .81 |

| 53. Someone made fun of you to make others laugh | .83 |

| 43. Someone who was mad at you tried to get back at you by not letting you be in their groupa | .82 |

| 50. Someone said they wouldn’t like you unless you did what he or she wanted | .83 |

| 56. Someone left you out on purpose when it was time to do an activitya | .81 |

| 57. Someone spread a false rumor about you | .81 |

| 58. Someone tried to keep others from liking you by saying mean things about you | .87 |

| Cyber Victimization factor | |

| 48. Someone used text-messaging to threaten to hurt you physically | .90 |

| 54. Someone used cell phone pictures to threaten to hurt you physically | .93 |

| 45. Someone used cell phone pictures to make fun of you | .85 |

| 60. Someone used text-messaging to make fun of you | .89 |

| 61. Someone used a chat room or Internet website to make fun of youa | .88 |

| 69. Someone called you mean names online or using a cell phone. | .84 |

| 68. Someone sent or posted embarrassing pictures of you without your permission. | .84 |

| 70. Someone pretended to be someone else online or using a cell phone to trick you. | .79 |

| 71. Someone left you out of an online group or unfriended you on Facebooka. | .86 |

| 72. Someone posted rude comments about you online. | .87 |

| 73. Someone spread rumors about you online or by texting.a | .82 |

| Delinquent Behavior factor | |

| 8. Stolen something | .78 |

| 25. Written things or sprayed paint on (tagged) walls or sidewalks or cars where you were not supposed to | .85 |

| 27. Taken something from a store without paying for it (shoplifted) | .83 |

| 32. Purposely damaged property that did not belong to you | .87 |

| 23. Snuck into someplace without paying, such as a movie, or onto a bus or subway | .80 |

| 26. Taken someone’s car or motorcycle for a ride without their permission (gone “joyriding”) | .86 |

| Substance Use factor | |

| 33. Drunk liquor (like whiskey or vodka) | .90 |

| 34. Drunk beer (more than a sip or taste) | .81 |

| 35. Been drunk | .91 |

| 36. Drunk wine or wine coolers (more than a sip or taste) | .89 |

| 37. Used marijuana (pot, hash, reefer, K2) | .88 |

| 41. Smoked cigarettes | .87 |

| 38. Sniffed glue, breathed the contents of aerosol spray cans, or inhaled any paints or prays to get high | .87 |

| 39. Used drugs (besides marijuana or inhalants), such as heroin, cocaine, LSD, or ecstasy | .90 |

| 40. Smoked cigars (like Black &Milds) | .82 |

Note. N = 3,216 observations from 1,263 participants. All loadings are significant at p < .001.

Item that could be deleted to create a shorter form based on reliability analyses.

Multiple group analyses indicated that the model specifying configural invariance (i.e., same structure) across sex fit the data very well (see Model 2 in Table 4). We found support for strong measurement invariance based on a slight improvement in fit indices when loadings and thresholds were constrained across sex (see Model 3). Imposing strong measurement invariance made it possible to examine mean differences for boys and girls. These analyses did not reveal significant sex differences in reported frequencies of in-person physical or relational aggression, delinquent behavior, or substance use. However, compared with girls, boys reported lower frequencies of cyber aggression, and in-person and cyber victimization (see Table 5). These reflected small differences for cyber aggression and in-person victimization (ds = −.22 and −.21, ps = .05, respectively), and a medium-sized difference for cyber victimization (d = −0.44, p < .05).

The model specifying configural invariance across the sixth, seventh and eighth grades (see Model 4 in Table 4) also fit very well, and there were again slight improvements in fit when strong measurement invariance was specified (see Model 5). Comparison of means across grades revealed significantly lower frequencies of both in-person relational aggression and in-person victimization in the seventh grade compared with the sixth grade (ds = −0.35 to −0.31). There were also significantly lower frequencies of both forms of in-person aggression, delinquent behavior, and in-person victimization in the eighth grade compared with the sixth grade (ds = −.53 to −.42). In contrast, there were no differences across grades in the reported frequency of engaging in or experiencing cyber aggression.

We also examined the reliability of the seven factors. In contrast to classical test theory, which provides a single index of reliability (typically alpha), item-response theory does not assume that measurement precision is consistent across the full range of scores on a measure. In contrast, it provides estimates of reliability at different levels of the underlying construct. As would be expected for our general school-based sample, scores on our measures of victimization, aggression, delinquent behavior, and substance use were positively skewed such that most were close to the mean. Our analysis of the In-Person Physical Aggression and In-Person Victimization factors revealed reliabilities of .70 or higher and in most cases .80 or higher for scores at or slightly above the mean up to values over 3.2 standard deviations above the mean. For the other five factors, reliabilities were .70 or higher and generally .80 or higher for scores between 0.8 to 4.0 standard deviations above the mean. This indicates that the PBFS-AR had high reliability for differentiating among individuals with scores above the mean, but poorer reliability for differentiating among individuals with scores at the lower end of the scale. The failure to find support for distinct forms of Cyber Aggression, Cyber Victimization, and In-Person Victimization factors resulted in overall factors with 11 to 15 items. Examination of the item-information curves for these factors indicated that these scales could be shortened by two, three, and five items, respectively, with only a negligible decrease in reliability These items are identified in Table 6 and may be used to create a shorter version of the PBFS-AR.

Relations with Disciplinary Data

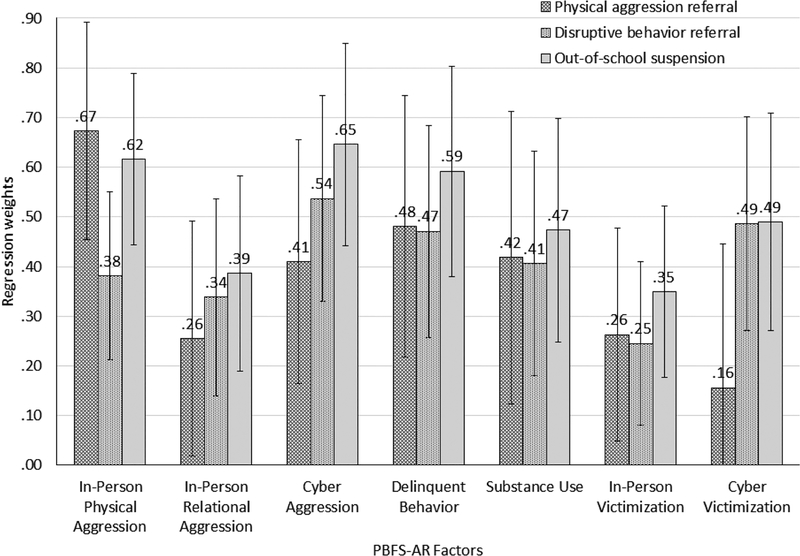

Standardized regression weights representing the relations between the PBFS-AR factors and the office discipline referrals are reported in Figure 1. Because factor variances were constrained to 1.00, these coefficients are comparable to Cohen’s d. Students with office referrals for physical aggression reported significantly higher frequencies on the PBFS-AR for all three forms of aggression, as well as for delinquent behavior and substance use. These were small-to-medium differences based on Cohen’s (1992) criteria for small, medium, and large effect sizes (ds = .26 to .48, p < .05), except for In-Person Physical Aggression, for which a larger difference was found (d = .67, p < .001). Students with office referrals for physical aggression also reported higher rates of in-person (d = .26, p = .018), but not cyber victimization (d = .16, p = .279). Students with office referrals for disruptive behavior reported significantly higher frequencies of aggression, delinquent behavior, and substance use, with small-to-medium differences (ds = .34 to .54, p < .001), as well as higher frequencies of both in-person (d = .25, p < .01) and cyber (d = .49, p < .001) victimization.

Figure 1:

Regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals representing differences on PBFS-AR factors for students with one or more office discipline referrals for physical aggression, one or more referrals for disruptive behavior, and one or more out-of-school suspension versus those with none. Models controlled for sex, grade, and intervention status. Dependent variables have a variance of 1.00, such that coefficients are equivalent to d-coefficients.

Students with out-of-school suspensions also reported significantly higher frequencies of engaging in problem behaviors, and experiencing victimization (all ps < .001). Larger differences were found for both physical and cyber aggression (d = .62 and .65, respectively) than for relational aggression (d = .39). Those with one or more out-of-school suspensions also reported higher frequencies representing medium-sized effects for delinquent behavior, substance use, and cyber victimization (ds = .47 to .59), and a higher frequency of in-person victimization representing a small-to-medium size difference (d = .35).

Discussion

The primary objectives of this study were to compare competing models of the structure of victimization and adolescent problem behaviors, including aggression, substance use, and other delinquent behavior, and to evaluate the validity of the PBFS-AR based on its relations to school office discipline referrals. A key question was the extent to which there are separate factors representing physical, verbal, and relational forms of aggression and victimization, and whether these distinctions are evident in both in-person and cyber forms of aggression and victimization. The results of this study were generally consistent with both theory and the findings of other studies that have made a case for differentiating between physical and relational aggression (for a review see Voulgaridou & Kokkinos, 2015). Specifically, we found support for in-person physical and relational acts as distinct forms of aggression. However, the evidence was less clear for verbal aggression. This lack of clarity is consistent with the results of Farrell et al.’s (2016) analyses of the structure of in-person aggression. They found that correlations between verbal aggression and some constructs (e.g., teacher ratings of aggression, norms for aggression) were similar to those found for physical aggression. However, correlations between verbal aggression and other constructs (e.g., teacher ratings of adaptive behavior, delinquent peer associations) were more similar to those found for relational aggression.

Whereas the literature has been clear in differentiating between physical and relational aggression, it is less clear where verbal aggression fits within this framework. This lack of differentiation may reflect a lack of conceptual clarity regarding the definition of verbal aggression. Physical and relational aggression are defined based on intent. Physical aggression involves the intent to cause physical harm, whereas relational aggression involves the intent to damage social relationships (Voulgaridou & Kokkinos, 2015). Items are defined as verbal aggression based solely on the mode of delivery, which may not reflect the intent or context. For example, insulting someone or calling them names may represent a direct attack on the individual’s sense of self or worth, a precursor to a physical confrontation, or an attempt to damage the individual’s social standing in a public setting. Verbal aggression may encompass a range of behaviors, some of which are more closely related to physical aggression, some of which are more closely related to relational aggression, and some of which sit squarely in the middle. For example, in this study, the items “Yelled at someone or called them mean names” and “Put someone down to their face,” both of which could be construed as an attack designed to provoke, loaded solely on the In-Person Physical Aggression factor. In contrast, the items related to making fun of someone to make others laugh and saying something disrespectful about someone’s family, behaviors which are likely intended to damage an individual’s image or reputation, loaded more strongly onto the Relational Aggression factor. It is possible that previous studies that found an overt (or direct) aggression factor included items assessing verbal attacks that may have been precursors to physical aggression. Future studies may need to parse out verbal aggression items based on whether the intent is to provoke, harass, or taunt an individual, or to damage the individual’s image, reputation, or relationships.

In contrast to in-person aggression, we did not find support for distinct physical or relational forms of cyber aggression, which is consistent with previous work (Mehari & Farrell, 2018). This may be because items representing cyber forms of physical aggression involve threats of physical aggression rather than actual physical aggression. Although we were not able to differentiate among different forms within cyber aggression, we did find support for cyber aggression as distinct from in-person aggression. This supports the notion that perpetrating aggression via electronic communication technologies has unique aspects that may influence which adolescents are more likely to engage in this form of aggression. Interestingly, its patterns of relations with office disciplinary referrals was more similar to the pattern for physical aggression than to the pattern found for relational aggression. That is, perpetrating cyber aggression was associated with a higher likelihood of office referrals for disruptive behavior and suspensions than was perpetrating relational aggression. It is possible that perpetrating cyber aggression is indicative of more nonconforming or deviant behaviors, which is supported in part by the lower prevalence of cyber aggression compared to in-person aggression (e.g., Wang et al., 2009).

Our evaluation of the PBFS-AR found support for strong measurement invariance across sex and grade. Although measurement invariance is a prerequisite to making meaningful comparisons across groups (Widaman & Reise, 1997), few prior studies have evaluated the measurement invariance of aggression and victimization (e.g., Marsee et al., 2011; Marsh et al., 2011; Rosen et al., 2013). The finding of measurement invariance across sex and grade supports the use of the PBFS-AR for examining differences across these groups. We also found mean differences across both grade and sex. Cyber aggression had similar rates of prevalence across sixth, seventh, and eighth grade, whereas in-person aggression was highest in sixth grade, consistent with other trends suggesting that in-person aggression declines throughout middle school (Farrell, Goncy, Sullivan, & Thompson, 2017). The stability of cyber aggression throughout the course of middle school suggests that it continues to be reinforced, or at least not effectively addressed through informal social control, as adolescents grow. Interestingly, trends over the past ten years suggest that in-person aggression is decreasing (Waasdorp, Pas, Zablotsky, & Bradshaw, 2017), whereas cyber aggression appears to remain stable (Smith, 2012). Taken together, these findings suggest a need to incorporate and evaluate elements of cyber aggression prevention into violence prevention programming, and to target online norms to increase effective bystander intervention in cyber aggression situations.

Although we did not find sex differences in the mean frequency of physical or relational aggression, we found that boys reported lower frequencies of cyber aggression and victimization, and in-person victimization. Differences were small for cyber aggression and in-person victimization, with medium sized effects for cyber victimization. Most prior studies have found a higher frequency of direct aggression (i.e., physical and verbal) among boys compared with girls, and negligible sex differences in relational aggression (Card et al. 2008). Our study’s lack of significant sex differences in physical aggression may reflect our focus on a predominantly African American sample. This is consistent with Card et al.’s (2008) meta-analysis, which revealed smaller sex differences in the frequency of direct aggression in samples with higher percentages of minority youth, and smaller sex differences for self-report measures. Our finding of higher frequencies of cyber aggression and victimization among girls than among boys underscores the need for further research to replicate these findings and identify factors that are responsible for these differences, particularly the larger differences for cyber victimization.

Within both in-person and cyber media, we found little support for differentiating among the forms of victimization experienced by adolescents. Our findings differed from the findings of Farrell et al.’s (2016) study of the previous version of the PBFS-AR, which found support for distinct in-person relational and physical victimization factors. However, their study included a limited pool of victimization items (e.g., only one verbal victimization item). Our conclusions also differ from those of several studies of the Revised Peer Experiences Questionnaire (RPEQ), which was designed to assess multiple forms of both aggression and victimization. Prinstein, Boergers, and Vernbert (2001) found support for distinct factors representing overt and relational victimization. In a subsequent study of an expanded pool of items, De Los Reyes and Prinstein (2004) found support for separate factors representing overt, relational, and reputational victimization. In both studies, the factor structure was determined by exploratory rather than confirmatory analyses. Queirós and Vagos (2016) found support for the same three victimization factors as De Los Reyes and Prinstein in their analysis of a Portuguese translation of the RPEQ using a confirmatory factor analysis. Although the factors identified in these three studies of the RPEQ fit the data well, none of these studies evaluated competing models of its structure. It is therefore not clear how well the models they identified would improve upon the fit of models specifying a smaller number of factors. McLaughlin, Hatzenbuehler, and Hilt (2009), for example, found support for a measurement model of the RPEQ that included a single victimization factor that was based on parcels, where each parcel included items representing overt, relational, and reputational victimization items.

The current study suggests that whereas individual adolescents may differ in their propensity to engage in physical versus relational aggression, those who are victimized are likely to report multiple forms of victimization, though they may experience different forms from different people. There may be underlying commonalities of victimization experiences (e.g., threats to security, belongingness, and acceptance at the peer and/or school level) that supersede form and intended method of hurt or harm (i.e., physical versus relational). This is consistent with research that suggests victimization during adolescence can serve as a mechanism to marginalize or exclude youth from peer groups (Brown, 2004). This does not imply that different forms of victimization all have the same impact on adjustment. By definition, physical victimization causes physical harm, and all forms of victimization carry a risk for psychosocial adjustment difficulties. Prinstein et al (2001), for example, found that relational victimization was related to high school students’ concurrent levels of loneliness and low self-esteem even after controlling for overt forms of victimization and both overt and relational forms of aggression. Further work is needed to evaluate the value added by differentiating among specific forms of victimization, in particular the extent to which they differ in their impact on adjustment.

Although we did not find support for differentiating among forms of victimization within media, we did find that in-person and cyber forms of victimization appear somewhat distinct (but highly correlated, at r = .85). With few exceptions (e.g., Landoll et al., 2015), most prior research has not tested whether in-person and cyber victimization are separate constructs. Instead, researchers have generally based research questions, study design, and empirical analyses on the untested assumption that they are distinct phenomena. This study supports that commonly held assumption. Many researchers posit that cyber victimization may cause greater harm due to circumstances surrounding the perpetration of cyber aggression that may magnify its effect, including the possibility of an unlimited audience and revictimization through views and shares (or the victim choosing to review the aggressive behavior; e.g., Tokunaga, 2010). This underscores the need for longitudinal research to explore whether there are differences in severity or types of outcomes, or interaction effects (Salmivalli et al., 2013).

Our analysis of the relations between scores on the PBFS-AR and office discipline referrals and outcomes provided support for its criterion validity. Of particular note was the finding that students with office referrals for physical aggression differed more on the PBFS-AR Physical Aggression factor than on the other measures of aggression and problem behavior. This is despite the fact that these factors, particularly those representing different forms of aggression, were highly correlated. This provides some evidence of discriminant validity for this measure. Students with office referrals for disruptive behavior and those receiving out-of-school suspensions showed more consistent differences in their frequency of the three forms of aggression, delinquent behavior, and substance use. This is consistent with the notion that students who engage in each of these types of problem behaviors are also likely to engage in other behaviors viewed as disruptive and be subject to suspensions. Office referrals were also related to victimization. Adolescents who are victimized may behave in disruptive or deviant ways, which elicits discipline from their teachers and aggression from their peers. This is consistent with research that has identified a subset of adolescents described as aggressive-victims (Bettencourt & Farrell. 2013). Such youth are more likely to have poor emotion regulation, which may increase their likelihood of engaging in disruptive classroom behavior. It is also possible that adolescents who are victimized become more disruptive, perhaps due to feeling rejected, isolated, or unsafe.

Limitations

This study had several limitations that merit discussion. A key concern is the extent to which the findings might generalize to other sets of items, methods of assessment, and populations of students. Items on the PBFS-AR were derived from multiple sources including other similar measures and qualitative research with adolescents. Nonetheless, they represented a limited sample of the domain of interest. The lack of support for a separate factor representing verbal aggression may have been specific to the particular items used to represent this construct. As previously noted, this may reflect a lack of conceptual clarity regarding the construct and its operationalization (Voulgaridou & Kokkinos, 2015). A further limitation concerns the wording of the items used to assess in-person aggression and victimization. They do not explicitly state that it must occur in person. In some cases, particularly for physical aggression, this can reasonably be assumed. Other items (e.g., rumor-spreading, calling someone mean names, threatening to hurt someone) could occur through in-person interactions or through electronic communication technologies (Mehari et al., 2014). This may have artificially inflated the correlation between factors meant to represent in-person and cyber aggression and victimization. Despite this limitation, we found support for distinct factors representing each media. Another limitation is that the PBFS-AR did not assess sexual aggression either in-person or cyber (e.g., unwanted solicitation or sharing of sexual photos and sexually explicit comments or requests). This, in part, reflects the difficulty of getting schools to approve of including questions they consider particularly sensitive. Future research is needed to assess whether sexual aggression and victimization emerge as distinct constructs. Finally, the rapid development of new forms of technology and rapid changes in the popularity of social media sites such as Facebook and SnapChat favored by adolescents poses a particular challenge for measures designed to assess adolescents’ cyber behavior. Measures of cyber aggression and victimization may thus require frequent updating.

The fact that the PBFS-AR is based on adolescents’ self-report is also a limitation. Self-report is the most commonly used method to assess adolescents’ aggression and victimization (Furlong et al., 2010). Given its unique perspective, it provides an important source of data for understanding students’ engagement in problem behavior and victimization experiences. Nonetheless, further work is needed to explore the extent to which other approaches to measuring aggression, problem behaviors, and victimization would lead to similar findings regarding their structure. Our sample consisted of a predominantly African American sample of students from three middle schools, many of whom came from single-parent families in urban communities with high rates of poverty and crime. In addition, the majority of the data were collected while a school-level violence prevention program was being implemented. Further work is needed to determine the extent to which these results would generalize to other populations of students and other circumstances.

A further concern was the use of school disciplinary data as a criterion for evaluating the validity of students’ report. School office discipline referrals are based on teachers’ observations of students’ behaviors at school, their interpretation of these observations, and their decisions regarding whether or not to make an office referral (McIntosh et al., 2012). They are also limited to student behavior in the presence of teachers. Because the PBFS-AR items do not specify the context, student reports on these measures presumably reflect their behavior both at school and outside of school. School discipline referrals thus represent, at best, a subset of the behaviors assessed by the student-report measure. Teachers may also not be consistent in their decisions about when to make an office discipline referral and there is evidence to suggest bias in making these decisions (e.g., Skiba et al., 2011). Our finding of small-to-medium effects in our analysis of the relations between PBFS-AR factors and school discipline data is therefore in line with what might be expected. Unfortunately, each method of assessing student behavior has its own inherent limitations and there is no perfect criterion against which to validate student report.

Conclusion

Overall, this study supported the PBFS-AR as a promising self-report measure of adolescents’ frequency of victimization, aggression and other problem behaviors (see PBFS-AR Version 2 in Supplemental materials for the final version of the measure). Analyses of its structure demonstrated its ability to differentiate between in-person physical, in-person relational and cyber aggression and other problem behaviors (substance use and other delinquent behavior), and between in-person and cyber victimization. We also found support for strong measurement invariance across sex and grade. Finally, support for the criterion validity of the PBFS-AR was found based on its pattern of relations with school disciplinary data. Our analysis of the structure of the PBFS-AR also contributed to the literature on the nature of adolescents’ victimization and aggression. It supported the notion that in-person physical, in-person relational and cyber aggression represent highly correlated but distinct constructs. This was supported both by comparison of competing models of the factor structure of the PBFS-AR and the differential pattern of findings between In-Person Physical and In-Person Relational Aggression factors and office referrals for physical aggression. Our findings also highlighted the need for further research to clarify the construct of verbal aggression. Finally, it suggested that the distinction between forms of aggression found for measures of perpetration are less evident in measures of both in-person and cyber victimization.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01HD08994, by the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC Cooperative Agreement 5U01CE001956, and by the National Institute of Justice, grant number 2014-CK-BX-0009. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the National Institute of Justice.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

Contributor Information

Albert D. Farrell, Virginia Commonwealth University

Erin L. Thompson, Virginia Commonwealth University

Krista Mehari, University of South Alabama.

Terri N. Sullivan, Virginia Commonwealth University

Elizabeth A. Goncy, Cleveland State University

References

- Asparouhov T & Muthén B (2006). Robust chi square difference testing with mean and variance adjusted test statistics. Mplus Web Notes: No. 10. May 26, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt AF, & Farrell AD (2013). Individual and contextual factors associated with patterns of aggression and peer victimization during middle school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 285–302. 10.1007/s10964-012-9854-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw CP, Waasdorp TE, & Johnson SL (2015). Overlapping verbal, relational, physical, and electronic forms of bullying in adolescence: Influence of school context. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 44, 494–508. 10.1080/15374416.2014.893516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB (2004). Adolescents’ relationships with peers In Lerner R and Steinberg L (Eds.), Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, (pp. 363–394). Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons; 10.1002/9780471726746.ch12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Card NA, Stucky BD, Sawalani GM, & Little TD (2008). Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic review of gender differences, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment. Child Development, 79, 1185–1229. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01184.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, & Rensvold RB (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255. 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112 (1), 155–159. 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, & Grotpeter JK (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development, 66(3), 710–22. 10.2307/1131945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg L, Toal S,. Swahn M, & Behrens C (2005) Measuring violence-related attitudes, behaviors, and influences among youths: A compendium of assessment tools, 2nd ed Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, & Kazdin AE (2005). Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychological Bulletin, 131(4), 483–509. 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, & Prinstein MJ (2004). Applying depression-distortion hypotheses to the assessment of peer victimization in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 325–335. 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Ampy LA, & Meyer AL (1998). Identification and assessment of problematic interpersonal situations for urban adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 27(3), 293–305. 10.1207/s15374424jccp2703_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Goncy EA, Sullivan TN, & Thompson E (2017). Victimization, aggression, and other problem behaviors: Trajectories of change within and across middle school grades. Journal Research on Adolescence. Advance online publication. 10.1111/jora.12346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Kung EM, White KS, & Valois R (2000). The structure of self-reported aggression, drug use, and delinquent behaviors during early adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29, 282–292. 10.1207/S15374424jccp2902_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Sullivan TN, Goncy EA, & Le AH (2016). Assessment of adolescents’ victimization, aggression, and problem behaviors: Evaluation of the Problem Behavior Frequency Scale. Psychological Assessment, 28(6), 702–714. 10.1037/pas0000225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Sullivan TN, Sutherland KS, Corona R, & Masho S (2018). Evaluation of the Olweus Bully Prevention Program in an urban school system in the USA. Prevention Science. Advance online publication. 10.1007/s11121-018-0923-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlong MJ, Sharkey JD, Felix ED, Tanigawa D, & Green JG (2010). Bullying assessment: A call for increased precision of self-reporting procedures In Simerson JR, Swearer SM, & Espelage DL (Eds.), Handbook of bullying in schools: An international perspective (pp. 329–346). New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Galen BR, & Underwood MK (1997). A developmental investigation of social aggression among children. Developmental Psychology, 33, 589–600. 10.1037/0012-1649.33.4.589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Taylor BJ, & Cumsille PE (2001) Planned missing data designs in the analysis of change In Collins LM & Sayer AG (Eds.). New methods for the analysis of change (pp. 335–353). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 10.1037/10409-011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt C, Peters L, & Rapee RM (2012). Development of a measure of the experience of being bullied in youth. Psychological Assessment, 24, 156–165 10.1037/a0025178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R (2014). Problem behavior theory: A half-century of research on adolescent behavior and development In Lerner RM, Petersen AC, Silbereisen RK, & Brooks-Gunn J (Eds.), The developmental science of adolescence: History through autobiography. (pp. 239–256). New York, NY: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe LJ, Kann L, & Collins JL (1993). Overview of the youth risk behavior surveillance system. Public Health Reports (Washington, D.C.: 1974),108, 2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski RM, Giumetti GW, Schroeder AN, & Lattanner MR (2014). Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin, 140, 1073–1137. 10.1037/a0035618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landoll RR, La Greca AM, Lai BS, Chan SF, & Herge WM (2015). Cyber victimization by peers: Prospective associations with adolescent social anxiety and depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence, 42, 77–86. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsee MA, Barry CT, Childs KK, Frick PJ, Kimonis ER, Muñoz LC, . . . Lau KSL (2011). Assessing the forms and functions of aggression using self-report: Factor structure and invariance of the Peer Conflict Scale in youths. Psychological Assessment, 23, 792–804. 10.1037/a0023369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Nagengast B, Morin AJS, Parada RH, Craven RG, & Hamilton LR (2011). Construct validity of the multidimensional structure of bullying and victimization: An application of exploratory structural equation modeling. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103, 701–732. 10.1037/a0024122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh K, Fisher ES, Kennedy KS, Craft CB, & Morrison GM (2012). Using office discipline referrals and school exclusion data to assess school discipline In Jimerson SR, Nickerson AB, Mayer MJ, & Furlong MJ (eds.), Handbook of school violence and school safety (pp. 305–315). New York, NY, US: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]