Abstract

The treatment of adult osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH), with 8.12 million patients in China, remains a challenge to surgeons. To standardize and improve the efficacy of the treatment of ONFH, Chinese specialists updated the experts' suggestions in March 2015, and an experts' consensus was given to provide a current basis for the diagnosis, treatment and evaluation of ONFH. The current guideline provides recommendations for ONFH with respect to epidemiology, etiology, diagnostic criteria, differential diagnosis, staging, treatment, as well as rehabilitation. Risk factors of non‐traumatic ONFH include corticosteroid use, alcohol abuse, dysbarism, sickle cell disease and autoimmune disease and others, but the etiology remains unclear. The Association Research Circulation Osseous (ARCO) staging system, including plain radiograph, magnetic resonance imaging, radionuclide examination, and histological findings, is frequently used in staging ONFH. A staging and classification system was proposed by Chinese scholars in recent years. The major differential diagnoses include mid−late term osteoarthritis, transient osteoporosis, and subchondral insufficiency fracture. Management alternatives for ONFH consist of non‐operative treatment and operative treatment. Core decompression is currently the most common procedure used in the early stages of ONFH. Vascularized bone grafting is the recommended treatment for ARCO early stage III ONFH. This guideline gives a brief account of principles for selection of treatment for ONFH, and stage, classification, volume of necrosis, joint function, age of the patient, patient occupation, and other factors should be taken into consideration.

Keywords: Diagnosis, Guideline, Osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH), Treatment

Introduction

Osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH), also known as avascular necrosis of the femoral head (AVNFH) or aseptic necrosis of the femoral head (ANFH), continues to be a challenging disease to treat. The normative and effective choice of treatment is determined according to age and pathological staging. The etiology remains unclear, and it often affects young patients who want to maintain an active lifestyle. In 2007, Chinese experts reached a consensus on the main aspects of diagnosis and treatment and issued recommendations (2007). Guidelines were published in the following document: Chinese Experts' Consensus on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Osteonecrosis of the Femoral Head in Adults (2012), which now plays an important role in the standardization of the diagnosis and treatment of ONFH. Some shortcomings are still present in the clinical application of these guidelines. To standardize and improve the efficacy of the treatment of ONFH, the group from the Microsurgery Department of the Orthopedics branch of the Chinese Medical Doctor Association and the group from the Bone Defect and Osteonecrosis branch of the Chinese Association of Reparative and Reconstructive Surgery sponsored a senior experts' seminar on ONFH and updated the experts' suggestions in March 2015. All members of the microsurgery groups and the senior experts were invited to discuss the latest concepts and debate on the diagnosis and treatment of ONFH. Finally, an experts' consensus was given to provide a current basis for the diagnosis, treatment and evaluation of ONFH.

Definition

Osteonecrosis of the femoral head is not a specific diagnostic entity, but is considered to be a very complicated pathophysiological process that involves venous congestion and the impairment or interruption of the blood supply to the femoral head, causing cell death within the femoral head. Histologically, ONFH is characterized by dead osteocytes, necrotic marrow elements, and a lack of vasculature in a defined region in the femoral head. In most cases, these changes ultimately lead to collapse of the subchondral bone and the destruction of the hip joint in patients1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10.

Epidemiology

There are an estimated 8.12 million ONFH cases among Chinese people aged 15 years and older. The prevalence of ONFH per 10,000 people for each demographic subgroup was as follows: 11.76 per 100,000 in plain farmers, 9.57 per 100,000 in city residents, 7.92 per 100,000 in workers, 6.29 per 100,000 in hill farmers, and 5.53 per 100,000 in coastal fishermen. The prevalence of ONFH was significantly higher in males than females. Among ONFH patients, residents of northern China had a higher prevalence of ONFH than residents of southern China11, 12.

Etiology

The etiology of ONFH includes traumatic and non‐traumatic causes. ONFH commonly occurs after direct trauma, such as femoral neck or head fracture, acetabular fracture, hip dislocation, or severe sprain or contusion of the hip13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18. The pathogenesis of non‐traumatic ONFH is not well understood, and the main risk factors in China include corticosteroid use, alcohol abuse, dysbarism, sickle cell disease, and autoimmune disease (systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome), as well as chemotherapy, radiation, Caisson disease, pancreatitis, Gaucher disease, and smoking6, 12, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Etiologic factors associated with osteonecrosis

| Causes | Diseases |

|---|---|

| Trauma | Hip dislocation |

| Femoral neck fracture | |

| Femoral head fracture | |

| Corticosteroid use | Solid organ transplantation |

| Bone marrow transplantation | |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| Alcohol consumption | |

| Coagulation disorders | Antithrombin III deficiency |

| Protein C deficiency | |

| Protein S deficiency | |

| Thrombocytosis | |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | |

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection | |

| Hemoglobinopathy | Sickle cell disease |

| Thalassemia | |

| Polycythemia | |

| Metabolic disease | Gaucher's disease |

| Gout | |

| Other rare disorders | Hyperlipidemia |

| Liver disease | |

| Dysbaric phenomenon | |

| Miscellaneous factors | Smoking |

| Pregnancy | |

| Chemotherapy | |

| Radiation |

Diagnostic Criteria

The diagnostic criteria were determined using the Chinese Experts' Consensus on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Osteonecrosis of the Femoral Head in Adults and the international diagnostic criteria for osteonecrosis of the femoral head1, 6, 7, 8.

Clinical Symptoms, Signs and Medical Histories

Although early in the disease process the condition is painless, the chief complaint of a patient with osteonecrosis is pain with limitation of movement. The pain is usually localized to the groin area, but occasionally it can involve the ipsilateral buttock and knee or the greater trochanteric area. The pain has been described as a deep, intermittent, throbbing pain, with an insidious onset that can be sudden. The pain is exacerbated with weight‐bearing and is relieved by rest.

Physical examination reveals pain with both active and passive range of motion, especially with forced internal rotation. A limitation of passive abduction is usually elicited, and passive internal and external rotation of the extended leg can cause pain.

The medical history usually includes excessive corticosteroid use, alcohol abuse, smoking, coagulopathies, hemoglobinopathy, gout, systemic lupus erythematosus, and chemotherapy or exposure to radiotherapy. Patients with traumatic ONFH should provide a history of hip injury that includes dislocations and fractures6, 11, 12, 20.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) achieves excellent sensitivity for early ONFH detection25, 26, 27, 28. Diagnoses can be made on the T1‐weighted axial localizer and T1‐weighted or T2‐weighted spin‐echo coronal images. The necrotic margin is evident as a single line on T1‐weighted images and a double line on T2‐weighted images. The double‐line sign is also a specific and pathognomonic sign in non‐traumatic osteonecrosis and is observed in concentric low and high signal‐intensity bands on the T2‐weighted image26, 29, 30.

Radiography

Standard anteroposterior and frog‐leg (Lowenstein) lateral radiographs should be obtained in both legs as part of a patient's work‐up because bilateral disease is common. The delineation of small areas of ONFH on plain radiographs may be difficult, but the most common early findings are mottled radiodense and radiolucent areas on the subchondral portion of the anterosuperior part of the femoral head. The presence of the crescent sign corresponds with the progression of ONFH, reflecting the discrepancy in densities of the femoral head because of subchondral bone collapse. In addition, the final stages of joint space narrowing, acetabular changes, or both, and advanced degenerative changes can be observed31.

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography scans (CT) show diagnostic findings in advanced stages and are less sensitive in the early stages of osteonecrosis. CT scans of the femoral head show that the necrotic and repairing bone is in the surrounding sclerotic bone; a subchondral bone fracture may also be observed, but CT scans are less sensitive than MRI32, 33, 34.

Radionuclide Examinations

Radionuclide bone scintigraphy using technetium‐labeled phosphate analogs such as methylene diphosphonate (99mTc‐MDP) and dicarboxypropane diphosphonate (99mTc‐DPD) may be used for the early diagnosis of ONFH. In the acute phase of osteonecrosis, a decreased or absent uptake of bone tracer (“cold” lesion) can be observed. After weeks or months, an increased accumulation of bone tracer occurs (“hot” lesion) with chronic vascular stasis in repair and in revascularization35. Single‐photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) may improve radionclide sensitivity for the diagnosis of osteonecrosis36, 37. Positron emission tomography (PET) scans provide a real‐time image of physiology based on the type of radiolabeled marker used. It may be possible that PET scans detect osteonecrosis earlier than MRI and SPECT scans and predict the progression as well as the outcome of osteonecrosis38.

Pathologic Diagnosis of Core Biopsy

A core biopsy of the diseased femoral head shows that empty lacunae were observed in more than 50% of the bone trabeculae, and damage of many adjacent bone trabeculae and bone marrow necrosis was also present.

Digital Subtraction Angiography

This procedure can be used to assess venous congestion and impaired or interrupted blood supply to the femoral head, which can cause cell death within the femoral head. This invasive procedure is not recommended as a routine investigation.

Ascertaining the history and clinical symptoms combined with any of the other signs is primary to making a diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Mid–late Term Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis is the most common cause of chronic joint pain among middle‐aged and older people. Osteoarthritis involves the entire joint, including the nearby muscles, underlying bone, ligaments, joint lining (synovium), the joint cover (capsule), and the joint space narrowing of the hip. CT scans show sclerotic bone and cystic changes; the crescent sign can be observed on MRI.

Acetabular Dysplasia Secondary Osteoarthritis

This condition most commonly affects female children and young adults bilaterally. X‐rays show dislocation of the hip joint, joint space narrowing of the hip, and features of secondary osteoarthritis.

Ankylosing Spondylitis Involving the Hip

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a common inflammatory rheumatic disease that affects the axial skeleton, causing characteristic inflammatory back pain, which can lead to structural and functional impairments and a decrease in the quality of life. The pathogenesis of AS is poorly understood. Immune‐mediated mechanisms involving human leucocyte antigen (HLA)‐B27 are associated with the pathogenesis of AS. Involvement of the hip is common among patients with AS and is understood to be a result of inflammation of the subchondral bone marrow. Hip involvement often affects bilateral femoral heads, and radiography shows sacroiliac joint erosions and iliac‐side subchondral sclerosis.

Idiopathic Transient Osteoporosis of the Hip

Idiopathic transient osteoporosis of the hip (ITOH) occurs mostly in middle‐aged men but can sometimes occur in women, usually in late pregnancy. An increase in pain and a limp is observed, accompanied by some local muscle wasting. An abnormal bone scan may precede radiographic osteoporosis of the femoral head and neck. Symptoms reach a plateau and then resolve, and bone density returns to normal. MRI shows low signal intensity on T1WI and high signal intensity on T2WI, extending from the femoral head to the intertrochanteric region39, 40, 41.

Chondroblastoma in the Femoral Head

Chondroblastoma is a benign bone tumor arising most often in the epiphyses of long bones, but can also affect the proximal femur. Nearly 90% of these tumors occur in patients between the ages of 5 and 25 years. MRI shows high signal intensity on T2WI. CT scans show irregular dissolved bone.

Subchondral Insufficiency Fracture

Subchondral insufficiency fractures (SIF) occur mostly in women over 60 years of age with osteoporosis. The initial symptom is acute onset of hip pain. Radiologically, a subchondral collapse mainly in the superolateral segment of the femoral head is noted. One of the characteristic MRI findings is the shape of a low‐intensity band on T1WI and high‐intensity T2WI (bone marrow edema pattern) that is generally irregular, serpiginous, convex to the articular surface, and often discontinuous42, 43.

Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis

Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) is a rare disorder affecting joints and a benign proliferative disorder of the synovium with uncertain cause. PVNS occurs mostly in the second and the fourth decade of life. No significant sex preponderance has been reported. This condition may involve tendon sheaths, bursae, or joints, the latter occurring as diffuse involvement or a localized nodule. X‐rays and CT scans show narrowing of the hip joint space. MRI shows extensive thickening of the joint lining or an extensive mass, possibly with destructive bone changes.

Bone Infarction

A bone infarct occurs with ischemic death of the cellular elements of the bone and marrow. This condition affects bilateral hip joints. MRI shows high signal intensity on T2‐W images and the appearance of the characteristic double‐line sign, which consists of a hyperintense inner ring and a hypointense outer ring (Table 2).

Table 2.

Differential diagnosis of diseases analogous to osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH)

| Diseases | Age predilection | Sex predilection | Etiology | Unilateral or Bilateral | Acetabulum involved or not | Diagnosis elements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteoarthritis | Middle‐age and older | No gender differences | Degeneration | Bilateral | Yes | CT: sclerotic bone and cystic change |

| MRI: crescent sign | ||||||

| Acetabular dysplasia secondary osteoarthritis | Children and youth | Female | Genetic factors | Bilateral | Yes | X‐rays: hip joint dislocation, hip joint space narrowing and features of secondary osteoarthritis |

| Ankylosing spondylitis involving the hip | Teenagers | Male | Genetic factors and environment | Bilateral | Yes | HLA‐B27(+), sacroiliac joint erosions and iliac side subchondral sclerosis |

| Idiopathic transient osteoporosis of the hip (ITOH) | Middle‐aged and youth | No gender differences | None | Unilateral | No | MRI: low signal intensity on T1WI, high signal intensity on T2WI, extending from the femoral head to the intertrochanteric region |

| Chondroblastoma in femoral head | Children and teenager | Male | Unclear | Unilateral | No | MRI: high signal intensity on T2WI; CT: irregular dissolved bone |

| Subchondral insufficiency fracture | Elderly | Female | Osteoporosis | Unilateral | No | X‐rays: femoral head becomes flat; MRI: subchondral low signal intensity on T1WI and T2WI, with bone marrow edema pattern |

| Pigmented villonodular synovitis | Young adults | No gender differences | None | Unilateral | Yes | X‐rays and CT: hip joint space narrowing; MRI: extensive thickening of the joint lining or an extensive mass, possibly with destructive bone changes |

| Bone Infarction | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Bilateral | No | MRI: high signal intensity on T2WI, characteristic double‐line sign, which consists of a hyperintense inner ring and a hypointensity outer ring |

CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Staging

Various classification systems have been proposed and used to distinguish the different stages and necrotic extent of femoral head osteonecrosis, including the systems described by Marcus and co‐authors Ficat and Arlet, Steinberg and associates, and the classification system of Ohzono and associates. The extent of necrosis has been evaluated using the Steinberg system or the Japanese Investigation Committee (JIC) classification. The Association Research Circulation Osseous (ARCO) staging system was considered more systematic and more comprehensive than any other type of staging system developed by scholars. The first ARCO staging system was designed in Nijmegen, Netherlands at a meeting by the members of the ARCO in May 1991. This modification was discussed and approved at the General Assembly of ARCO in 1994 (Table 3)44. The Chinese staging system was designed by Chinese scholars in recent years (Table 4)45.

Table 3.

Association Research Circulation Osseous (ARCO) international classification of osteonecrosis44

| Stage | 0 | 1 | 2 | Early 3 | Late 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Findings | All present normal or non‐diagnostic | Normal on X‐ray and CT; abnormal on scintigraph, and/or MRI | No crescent sign; X‐ray: sclerosis, osteolysis, and focal porosis | Crescent sign; X‐ray: flattening of articular surface of femoral head; no collapse | X‐ray: collapse; flattening of articular surface of femoral head. | Osteoarthritis sign: joint space narrowing, acetabular changes, and joint destruction |

| Techniques | X‐ray, CT, scintigraph, MRI | Scintigraph, MRI, quantitate on MRI | X‐ray, CT, scintigraph, MRI, quantitate on MRI and X‐ray | X‐ray, CT, quantitate on X‐ray | X‐ray, CT, quantitate on X‐ray | X‐ray |

| Location | NO |

Medial

|

Central

|

Lateral

|

NO | |

| Quantitation | NO | Involvement of femoral head: minimal A <15%; moderate B 15%–30%; extensive C >30% |

Length of crescent: A <15% B 15%–30% C >30% |

Surface collapse and dome depression

A: <15%/<2 mm B: 15%–30%/2–4 mm C: >30%/>4 mm |

NO | |

CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Table 4.

Chinese staging of osteonecrosis of the femoral head45

| Stage | Clinical findings | Radiographic signs | Pathological changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| I (pre‐clinical, no‐collapse) | No | MRI | Necrosis of bone marrow |

| According to size of necrotic are | Bone scan | Necrosis of osteocytes | |

| I a, small <15% | |||

| I b, medium 15%–30% | |||

| I c, large >30% | |||

| II (early stage, no‐collapse) | No or slight pain | MRI | Necrotic area absorbed |

| X‐rays | Bone repair | ||

| According to size of necrotic area | CT | ||

| II a, small <15% | |||

| II b, medium 15%–30% | |||

| II c, large >30% | |||

| III (medium stage, pre‐collapse)† | On set of pain | MRI T2‐WI: bone marrow edema, CT: subchondral fracture, X‐rays: Femoral head contour interrupted Crescent sign | Subchondral fracture or fracture through necrotic bone |

| Slight claudication | |||

| According to length of crescent | Moderate pain | ||

| Limited internal rotation | |||

| III a, small <15% | Pain in internal rotation | ||

| III b, medium 15%–30% | |||

| III c, large >30% | |||

| IV (middle–late stage, collapse)‡ | Moderate to severe pain | X‐rays: femoral head collapse with normal joint space | Femoral head collapse |

| Claudication | |||

| According to depth of collapse | Limited internal rotation | ||

| Aggravated pain when strenuous internal rotation | |||

| IV a, slight <2 mm | |||

| IV b, medium 2–4 mm | Limited abduction and adduction | ||

| IV c, severe >4 mm | |||

| V (late‐stage, osteoarthritis) | Severe pain | X‐ray: flattening of femoral head, narrow joint space, acetabular cystic changes or sclerosis | Cartilage involved, osteoarthritis |

| Severe claudication | |||

| Limited range of motion |

Estimation of necrotic area: necrotic area should be estimated in stages I and II on a mid‐coronal section of the femoral head on MRI or CT (small <15%, medium 15%–30%, large >30%), the volume of the necrotic area being estimated through the involved layers.

When X‐ray films show no‐collapse, patients with painful hips need to undergo MRI and CT examination. Necrosis has progressed to collapse (stage III) if bone marrow edema or subchondral fracture have occurred.

When collapse has occurred and patients have experienced pain for more than 6 months, articular cartilage will have clearly degenerated (stage V).

CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Treatment of Osteonecrosis of the Femoral Head

Management alternatives for ONFH include non‐operative treatment and operative treatment. Factors affecting the outcome of these procedures include patients' age, etiology and stage of osteonecrosis, and the size and location of the osteonecrotic lesion.

Non‐operative Treatment

Non‐surgical management can only be selected for early stages and very small lesions or among patients in whom surgical management is contraindicated.

Weight Bearing

Recommendations include avoiding collision and combat sports. The use of two crutches can reduce pain, but wheelchair use must not be encouraged.

Treatment with Drugs

Recommendations include anticoagulants, fibrinolytic agents, vasodilators, and lipid‐lowering drugs46, 47. These agents include low‐molecular‐weight heparin, alprostadil, and warfarin compounded with lipid‐lowering drugs. Application of drugs that inhibit osteoclasts and increase osteogenesis are recommended, such as phosphate preparations and Madopar etc48, 49, 50. These drugs can be used alone and can be applied in patients with a history of hip surgery.

Traditional Chinese Medicine Treatment

In accordance with the holistic concept of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), the principles of dynamic and static combinations, an equal emphasis on bones and muscles, combined internal and external therapies, and doctor–patient cooperation methods are followed. Activating blood circulation, clearing dampness, resolving phlegm, and reinforcing the kidney to strengthen the bone are other TCM techniques used to treat the early stages of ONFH51, 52, 53.

Physiotherapies

These therapies include extracorporeal shockwave therapy, electromagnetic stimulation, and hyperbaric oxygen54, 55, 56.

Immobilization and Traction

These methods may be adopted in the early stages (ARCO stage 0 to stage I) and the middle stages (ARCO stage II to stage IIIb) of ONFH.

Operative Treatment

Non‐operative treatment is usually not very effective in ONFH; hence, most ONFH patients choose operative treatment to alleviate pain and retain mobility. Management alternatives for ONFH include joint salvaging procedures such as core decompression, non‐vascularized bone grafting, osteotomy, vascularized bone grafting, and joint arthroplasty1, 6, 7, 8. The most commonly used procedures are core decompression and vascularized bone grafting in the early stages (ARCO stage 0 to stage I) and middle stages (ARCO stage II to stage IIIb).

Core Decompression

Core decompression is currently the most common procedure used in the early stages of ONFH. Core decompression aims to decrease the intraosseous pressure and possibly enhance vascular ingrowth, thereby alleviating pain and delaying or negating the need for total hip arthroplasty. This technique uses a tunnel or percutaneous drilling through the proximal femur into the necrotic lesion57, 58. Core decompression has been shown to have a significantly higher success rate than nonsurgical management of early‐stage disease. The experts recommend that multiple small holes should be drilled to maximize efficacy of the procedure.

Core decompression is usually combined with implants of bone marrow stromal cells (implantation of autologous bone marrow cells). Many studies have reported the efficacy of this surgical technique59, 60, 61. Experts suggest that the core decompression with bone marrow stromal cells could be used for a large number of patients diagnosed with ONFH in established centers that use a long‐term follow‐up reporting system.

Non‐vascularized Bone Grafting

This procedure provides decompression of the femoral head, removal of necrotic bone, and structural support and scaffolding to allow repair and remodeling of subchondral bone62. The methods include impaction bone grafting and a strut bone graft with autogenous bone, allogeneic bone, and bone substitution material63, 64, 65, 66.

Osteotomy

Osteotomies are used to move the segment of necrotic bone away from the weight‐bearing region, thereby relieving stress. Two general types of osteotomies are used: angular intertrochanteric (varus and valgus) and rotational transtrochanteric. Total hip replacements performed after an osteotomy are often technically more difficult than replacements performed in patients with ONFH who have never had an osteotomy, and may not be successful in the long term67, 68.

Vascularized Bone Grafting

The rationale for vascularized bone grafting is that it allows decompression, provides structural support, and restores a vascular supply that had been deficient or nonexistent for a long period of time. Multiple published reports have discussed the use of vascularization around hip and fibular grafts6, 7, 8, 69, 70. Presently, seven distinct approaches for vascularization around a hip bone graft are used: iliac graft vascularization71, 72; vascularized greater trochanter graft73, 74, 75, 76; greater trochanter flap with a branch of the transverse lateral circumflex femoral artery73, 74, 75, 76; vascularized pedicled bone flap with the deep iliac circumflex vessels; greater trochanter flap with a branch of the transverse lateral circumflex femoral artery and iliac graft vascularization77; iliac graft with the deep branch of the medial circumflex femoral artery or a pedicled ilium periosteal flap; and a quadratus femoris muscle pedicle. The surgical technique of the vascularized iliac bone flap combined with a tantalum screw has a good short‐term effect78, 79. The result of vascularized fibular grafts was confirmed according to the technical characteristics of the grafts and the surgeons' proficiency in using the grafts80, 81, 82.

Joint Arthroplasty

Total hip replacement is indicated once the femoral head has collapsed and the hip joint has degenerated such that the articulation is compromised83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88. Recently, however, enthusiasm has been generated among some investigators who anticipate better results from resurfacing that incorporates improvements in techniques and biomaterials. Some elements should be taken into consideration as follows: corticosteroid use increases the rates of infection; osteoporosis leads to placement of the prosthetic into the acetabulum; high difficulty of operation is associated with hip replacements after operative treatment; and the curative effect in traumatic ONFH is better than in non‐traumatic ONFH.

Stages and Treatment

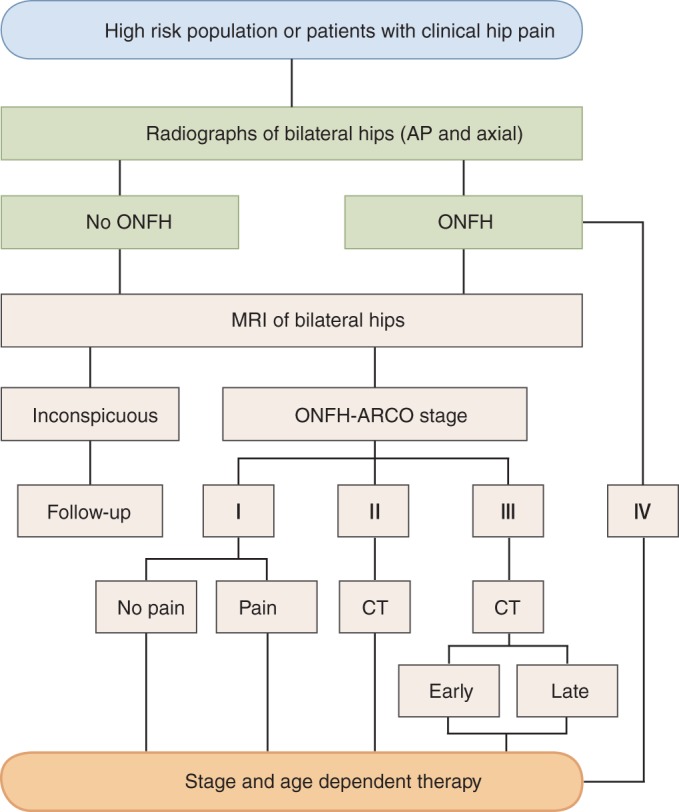

The choice of treatment for ONFH should take into consideration stage, classification, volume of necrosis, joint function, age of the patient, patient occupation, and other factors (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Clinical diagnosis flow chart of osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH). ARCO, Association Research Circulation Osseous; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Patients who have no clinical symptoms and a lesion area <15% in a non‐weight‐bearing area can receive regular follow‐up care. Asymptomatic ONFH patients who have a necrotic lesion that is more than 30% of the femoral head in a weight‐bearing area should receive active treatment before the occurrence of symptoms. Core decompression or non‐surgical treatment options can be taken89.

ARCO stage 0: If one extremity is diagnosed with ONFH, the contralateral side should be highly suspected. A follow‐up MRI is recommended every 3–6 months.

ARCO stage I and II: In patients who are symptomatic or have a necrotic lesion that is 15%–30% of the ONFH, non‐surgical treatment such as drug therapy may not be the best option; however, joint surgery using core decompression may be a more feasible treatment option57, 58, 90, 91, 92. Becoming qualified for stem cell transplantation or autologous bone marrow mononuclear cell transplantation is recommended at this stage. For patients who are classified as ARCO stage IIc, vascularized or non‐vascularized bone grafting (combined effectively with support materials), osteotomy, and other options should be considered66, 67, 68, 80, 93, 94, 95.

ARCO early stage III: Vascularized bone grafting (combined effectively with support materials) is the recommended treatment66, 67, 68, 80, 81.

ARCO later stage III: Joint arthroplasty or vascularized bone grafting (for a young patient) are the recommended treatment options81.

ARCO stage IV: A total hip replacement (THR) should be discussed with the patient. If the patient is young and wants joint‐preserving operative intervention, vascularized bone grafting is the recommended treatment.

Young adults: Core decompression (with implants including bone marrow stromal cells), vascularized bone grafting, and non‐vascularized bone grafting (15%–30% of necrosis volume) are the recommended treatment options.

Middle‐aged adults: Core decompression, vascularized bone grafting, nonvascularized bone grafting, and joint arthroplasty are the treatment recommendations.

Older individuals (>55 years of age): Joint arthroplasty, bipolar/tripolar hemiarthroplasty, or total hip replacement is the recommended treatment options.

Therapy Assessment and Rehabilitation

Therapy Assessment

Assessment of ONFH therapy can be determined by clinical and imaging evaluations96. Several hip rating scale systems (e.g. Harris, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index [WOMAC]) can be used to evaluate clinical outcomes. Meanwhile, gait analysis is recommended to add to the clinical data.

Imaging evaluation can be conducted using X‐ray and MRI scans. A concentric circle template can be used to observe the shape of the femoral head, the joint space, and the change in the acetabulum. Additional DSA should be performed in the vascular bone transplant cases to assess the supplemental blood and recovery77.

Rehabilitation Training

Experts suggest that it is necessary to establish detailed record keeping for continual assessment of therapy outcomes in ONFH patients. Rehabilitation training is an effective way to restore function and to prevent the ONFH patient from suffering from muscle disuse atrophy. Rehabilitation training should be focused on active rather than adjuvant treatment, gradually increasing the time and intensity and choosing an adequate way to exercise according to the stage of ONFH, the treatment, the hip rating scale and the result of the gait analysis97, 98. The following exercises were the consensus among the experts:

Lie supine with leg lifts: The patient lies supine and raises the affected leg, with the hip and knee flexed at 90°. This exercise should be performed 200 times per day but divided into three to four sessions. These exercises are especially useful in the conservative treatment of ONFH and during the postoperative period while the patient is recuperating in hospital.

Division and reunion: The patient sits on a chair with their feet at shoulder width and their hands on their knees. The patient then shifts the left leg to the left and the right leg to the right, stretching them fully in front and then adducting the limbs. This should be performed 300 times per day but divided into three to four sessions. These exercises are also used in the conservative treatment of ONFH and during the postoperative partial weight‐bearing stage.

Raise the leg in an erect position: The patient is asked to grasp onto a fixture, maintaining the erect position, and to raise the affected leg, keeping the body and legs at 90°, and the hip and knee flexed at 90°. This exercise should be repeated up to 300 times per day but divided into three to four sessions. This exercise may also be useful in the conservative treatment of ONFH and postoperatively during the partial weight‐bearing stage.

Squat with the help of a fixture: The patient is asked to grasp onto a fixture, maintaining the erect position, with feet at shoulder width. The patient then performs a squat and stands up. This exercise is repeated up to 300 times per day but divided into three to four sessions. This exercise could be useful in the conservative treatment of ONFH and postoperatively during the total weight‐bearing stage.

Adduction and abduction: The patient is asked to grasp onto a fixture, adduct, abduct, and perform a circle movement of the affected limb. This exercise is performed at least 300 times per day but divided into three to four sessions. These exercises are useful in the conservative treatment of ONFH and postoperatively during the total weight‐bearing stage.

Walking with a pair of crutches or cycling training: This method of ambulation or exercise may be used in the conservative treatment of ONFH and postoperatively during the total weight‐bearing stage.

List of Consultant Specialists

Ji‐ying Chen, Wei‐heng Chen, Wan‐shou Guo, Wei He, Yong‐cheng Hu, Peng‐de Kang, Zi‐rong Li, Bao‐yi Liu, Qiang Liu, You‐wen Liu, Hui Qu, Tie‐bing Qu, Ji‐rong Shen, Zhan‐jun Shi, Pei‐jiang Tong, Ai‐min Wang, Kun‐zheng Wang, Yan Wang, Yi‐sheng Wang, Xi‐sheng Weng, Hai‐shan Wu, Da‐chuan Xu, Zuo‐qin Yan, Shu‐hua Yang, Zong‐sheng Yin, Xiao‐bing Yu, Aihemaitijiang Yusufu, Ai‐xi Yu, Yu Zhang, Chang‐qing Zhang, and De‐wei Zhao.

Disclosure: This work was supported by grants from the NHFPC special fund for health scientific research in the public welfare (No. 201402016).

References

- 1. Mont MA, Zywiel MG, Marker DR, McGrath MS, Delanois RE. The natural history of untreated asymptomatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head: a systematic literature review. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2010, 92: 2165–2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhao DW. To strengthen the understanding of the pathophysiology in osteonecrosis of femoral head. Zhonghua Guan Jie Wai Ke Za Zhi Dian Zi Ban, 2014, 5: 1–3 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mont MA, Jones LC, Hungerford DS. Nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head: ten years later. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2006, 88: 1117–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cooper C, Steinbuch M, Stevenson R, Miday R, Watts NB. The epidemiology of osteonecrosis: findings from the GPRD and THIN databases in the UK. Osteoporos Int, 2010, 21: 569–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kang JS, Park S, Song JH, Jung YY, Cho MR, Rhyu KH. Prevalence of osteonecrosis of the femoral head: a nationwide epidemiologic analysis in Korea. J Arthroplasty, 2009, 24: 1178–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mont MA, Cherian JJ, Sierra RJ, Jones LC, Lieberman JR. Nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head: where do we stand today? A ten‐year update. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2015, 97: 1604–1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhao DW, Hu YC. Chinese experts' consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head in adults. Orthop Surg, 2012, 4: 125–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. The Microsurgery Department of the Orthopedics Branch of the Chinese Medical Doctor Association, The Osteonecrosis and Bone Defect Group of the Chinese Association of Reparative and Reconstructive Surgery . Chinese experts' consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head in adults (2012). Zhong Hua Gu Ke Za Zhi, 2012, 32: 606–610. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Powell C, Chang C, Gershwin ME. Current concepts on the pathogenesis and natural history of steroid‐induced osteonecrosis. Clin Rev. Allergy Immunol, 2011, 41: 102–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kang JS, Moon KH, Kwon DG, Shin BK, Woo MS. The natural history of asymptomatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Int Orthop, 2013, 37: 379–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhao DW, Yang L, Tian FD, et al. Incidence of osteonecrosis of the femoral head in divers: an epidemiologic analysis in Dalian. Zhonghua Gu Ke Za Zhi, 2012, 32: 521–525 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhao DW, Yu M, Hu K, et al. Prevalence of nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head and its associated risk factors in the Chinese population: results from a nationally representative survey. Chin Med J (Engl), 2015, 128: 2843–2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Panteli M, Rodham P, Giannoudis PV. Biomechanical rationale for implant choices in femoral neck fracture fixation in the non‐elderly. Injury, 2015, 46: 445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thompson GH, Lea ES, Chin K, Son‐Hing JP, Gilmore A. Closed bone graft epiphysiodesis for avascular necrosis of the capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2013, 471: 2199–2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ehlinger M, Moser T, Adam P, et al. Early prediction of femoral head avascular necrosis following neck fracture. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res, 2011, 97: 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bartonícek J, Vávra J, Bartoška R, Havránek P. Operative treatment of avascular necrosis of the femoral head after proximal femur fractures in adolescents. Int Orthop, 2012, 36: 149–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Palma LD, Santucci A, Verdenelli A, Bugatti MG, Meco L, Marinelli M. Outcome of unstable isolated fractures of the posterior acetabular wall associated with hip dislocation. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol, 2014, 24: 341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tannast M, Pleus F, Bonel H, Galloway H, Siebenrock KA, Anderson SE. Magnetic resonance imaging in traumatic posterior hip dislocation. J Orthop Trauma, 2010, 24: 723–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gangji V, Rooze M, De Maertelaer V, Hauzeur JP. Inefficacy of the cementation of femoral head collapse in glucocorticoid‐induced osteonecrosis. Int Orthop, 2009, 33: 639–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang Y, Yin L, Li Y, Cui Q. Preventive effects of puerarin on alcohol‐induced osteonecrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2008, 466: 1059–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mukisi‐Mukaza M, Gomez‐Brouchet A, Donkerwolcke M, Hinsenkamp M, Burny F. Histopathology of aseptic necrosis of the femoral head in sickle cell disease. Int Orthop, 2011, 35: 1145–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hua L, Zhang J, He JW, et al. Symptomatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head after adult orthotopic liver transplantation. Chin Med J (Engl), 2012, 125: 2422–2426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wessel JH, Dodson TB, Zavras AI. Zoledronate, smoking, and obesity are strong risk factors for osteonecrosis of the jaw: a case–control study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 2008, 66: 625–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Takahashi S, Fukushima W, Kubo T, Iwamoto Y, Hirota Y, Nakamura H. Pronounced risk of non‐traumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head among cigarette smokers who have never used oral corticosteroids: a multicenter case–control study in Japan. J Orthop Sci, 2012, 17: 730–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Steinberg DR, Steinberg ME. The University of Pennsylvania classification of osteonecrosis In: Koo KH, Mont MA, Jones LC, eds. Osteonecrosis. Heidelberg: Springer, 2014; 201–206. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mitchell DG, Rao VM, Dalinka MK, et al. Femoral head avascular necrosis: correlation of MR imaging, radiographic staging, radionuclide imaging, and clinical findings. Radiology, 1987, 162: 709–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ha YC, Jung WH, Kim JR, Seong NH, Kim SY, Koo KH. Prediction of collapse in femoral head osteonecrosis: a modified Kerboul method with use of magnetic resonance images. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2006, 88 (Suppl. 3): 35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li JD, Zhao DW, Cui DP, Yang L, Liu BY. Quantitative analysis and comparison of osteonecrosis extent of alcoholic ONFH using magnetic resonance imaging and pathology. Zhongguo Gu Yu Guan Jie Sun Shang Za Zhi, 2011, 26: 689–691 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 29. Malizos KN, Karantanas AH, Varitimidis SE, Dailiana ZH, Bargiotas K, Maris T. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head: etiology, imaging and treatment. Eur J Radiol, 2007, 63: 16–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Huang ZG, Zhang XZ, Wei HY, et al. Application of CT and MRI in volumetric measurement of necrotic lesion in patient with avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Zhong Hua Fang She Xue Za Zhi, 2012, 46: 820–824. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sun W, Li ZR, Yang YR, et al. Experimental study on phasecontrast imaging with synchrotron hard X‐ray for repairing osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Orthopedics, 2011, 34: e530–e534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dihlmann W. CT analysis of the upper end of the femur: the asterisk sign and ischaemic bone necrosis of the femoral head. Skeletal Radiol, 1982, 8: 251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mitchell DG, Kressel HY, Arger PH, Dalinka M, Spritzer CE, Steinberg ME. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head: morphologic assessment by MR imaging, with CT correlation. Radiology, 1986, 161: 739–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Conway WF, Totty WG, McEnery KW. CT and MR imaging of the hip. Radiology, 1996, 198: 297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ryu KN, Jin W, Park JS. Radiography, MRI, CT, bone scan and PET‐CT In: Koo KH, Mont MA, Jones LC, eds. Osteonecrosis. Heidelberg: Springer, 2014; 179–195. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Resnick D, Sweet DE, Madewell JE. Osteonecrosis: pathogenesis, diagnostic techniques, specific situations, and complications In: Resnick D, ed. Bone and Joint Imaging, 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2005; 1067–1088. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Motomura G, Yamamoto T, Karasuyama K, Iwamoto Y. Bone SPECT/CT of femoral head subchondral insufficiency fracture. Clin Nucl Med, 2015, 40: 752–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dasa V, Adbel‐Nabi H, Anders MJ, Mihalko WM. F‐18 fluoride positron emission tomography of the hip for osteonecrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2008, 466: 1081–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Korompilias AV, Karantanas AH, Lykissas MG, Beris AE. Transient osteoporosis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 2008, 16: 480–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Patel S. Primary bone marrow oedema syndromes. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2014, 53: 785–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Guler O, Ozyurek S, Cakmak S, Isyar M, Mutlu S, Mahirogullari M. Evaluation of results of conservative therapy in patients with transient osteoporosis of hip. Acta Orthop Belg, 2015, 81: 420–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ikemura S, Yamamoto T, Motomura G, Nakashima Y, Mawatari T, Iwamoto Y. The utility of clinical features for distinguishing subchondral insufficiency fracture from osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg, 2013, 133: 1623–1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yamamoto T. Subchondral insufficiency fractures of the femoral head. Clin Orthop Surg, 2012, 4: 173–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. JWM G, Gosling‐Gardeniers AC, WHC. R . The ARCO staging system: generation and evolution since 1991 In: Koo KH, Mont MA, Jones LC, eds. Osteonecrosis. Heidelberg: Springer, 2014; 215–218. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Joint Surgery Group of the Orthopaedic Branch of the Chinese Medical Association . Guideline for diagnostic and treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Orthop Surg, 2015, 7: 200–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yamaguchi R, Yamamoto T, Motomura G, et al. Effects of an antiplatelet drug on the prevention of steroid‐induced osteonecrosis in rabbits. Rheumatology, 2012, 51: 789–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Peled E, Davis M, Axelman E, Norman D, Nadir Y. Heparanase role in the treatment of avascular necrosis of femur head. Thromb Res, 2013, 131: 94–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fanord F, Fairbairn K, Kim H, Garces A, Bhethanabotla V, Gupta VK. Bisphosphonate‐modified gold nanoparticles: a useful vehicle to study the treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Nanotechnology, 2011, 22: 035102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chen CH, Chang JK, Lai KA, Hou SM, Chang CH, Wang GJ. Alendronate in the prevention of collapse of the femoral head in nontraumatic osteonecrosis: a two‐year multicenter, prospective, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Arthritis Rheum, 2012, 64: 1572–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Huang LX, Dong TH, Xie DH, Xu M. Reliminary observation of clinical results of treatment for early non‐traumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head with Madopar. Zhonghua Gu Ke Za Zhi, 2010, 30: 641–645 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 51. He W. Scientific view of the treatment of Chinese traditional medicine for non‐traumatic osteonecrosis of femoral head. Zhonghua Guan Jie Wai Ke Za Zhi Dian Zi Ban, 2013, 7: 284–286 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chen WH, Zhou Y, He HJ, et al. Treating early‐to‐middle stage nontraumatic osteonecrosis of femoral head patients by Jianpi Huogu recipe: a retrospective study. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi, 2013, 33: 1054–1058 (in Chinese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zhao DW, Huang SB, Wang BJ, et al. Therapeutic evaluation of WeishiHuogu I in treating avascular necrosis of femoral head in early‐middle stage. Zhonghua Guan Jie Wai Ke Za Zhi Dian Zi Ban, 2014, 5: 4–7 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wang CJ, Wang FS, Ko JY, et al. Extracorporeal shockwave therapy shows regeneration in hip necrosis. Rheumatology (Oxford), 2008, 47: 542–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Massari L, Fini M, Cadossi R, Setti S, Traina GC. Biophysical stimulation with pulsed electromagnetic fields in osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2006, 88 (Suppl. 3): S56–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cui C, Chang W, Yu AX, Cheng SH, Li HC. Hemorrheologic changes in steroid‐induced avascular necrosis of femoral head after hyperbaric oxygen treatment. Wu Han Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban, 2007, 28: 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bae JY, Kwak DS, Park KS, Jeon I. Finite element analysis of the multiple drilling technique for early osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Ann Biomed Eng, 2013, 41: 2528–2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kang P, Pei F, Shen B, Zhou Z, Yang J. Are the results of multiple drilling and alendronate for osteonecrosis of the femoral head better than those of multiple drilling? A pilot study. Joint Bone Spine, 2012, 79: 67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Persiani P, De CC, Graci J, Noia G, Gurzì M, Villani C. Stage‐related results in treatment of hip osteonecrosis with core‐decompression and autologous mesenchymal stem cells. Acta Orthop Belg, 2015, 81: 406–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhao D, Cui D, Wang B, et al. Treatment of early stage osteonecrosis of the femoral head with autologous implantation of bone marrow‐derived and cultured mesenchymal stem cells. Bone, 2012, 50: 325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mao Q, Jin H, Liao F, Xiao L, Chen D, Tong P. The efficacy of targeted intraarterial delivery of concentrated autologous bone marrow containing mononuclear cells in the treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head: a five year follow‐up study. Bone, 2013, 57: 509–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhang HJ, Liu YW, Du ZQ, et al. Therapeutic effect of minimally invasive decompression combined with impaction bone grafting on osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol, 2013, 23: 913–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yang S, Wu X, Xu W, Ye S, Liu X, Liu X. Structural augmentation with biomaterial‐loaded allograft threaded cage for the treatment of femoral head osteonecrosis. J Arthroplasty, 2010, 25: 1223–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Xiao X, Wang W, Liu D, et al. The promotion of angiogenesis induced by three‐dimensional porous beta‐tricalcium phosphate scaffold with different interconnection sizes via activation of PI3K/ Akt pathways. Sci Rep, 2015, 5: 9409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Gao P, Zhang H, Liu Y, et al. Beta‐tricalcium phosphate granules improve osteogenesis in vitro and establish innovative osteoregenerators for bone tissue engineering in vivo. Sci Rep, 2016, 6: 23367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Feng B, Zhang J, Wang Z, et al. The effect of pore size on tissue ingrowth and neovascularization in porous bioceramics of controlled architecture in vivo. Biomed Mater, 2011, 6: 015007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hamanishi M, Yasunaga Y, Yamasaki T, Mori R, Shoji T, Ochi M. The clinical and radiographic results of intertrochanteric curved varus osteotomy for idiopathic osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg, 2014, 134: 305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ito H, Tanino H, Yamanaka Y, et al. Long‐term results of conventional varus half‐wedge proximal femoral osteotomy for the treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 2012, 94: 308–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zhao DW. Minimally invasive surgery and microscopic repair in osteonecrosis of femoral head. Zhonghua Xian Wei Wai Ke Za Zhi, 2015, 38: 209–210 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhao DW. New methods and selection for head preserving therapy in osteonecrosis of femoral head. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi, 2011, 91: 3313–3315 (in Chinese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yang L, Zhao DW, Guo L, et al. Comparison analysis of the outcomes between ascending branch iliac graft and the transverse branch of greater trochanter bone graft with the lateral femoral circumflex artery in osteonecrosis of femoral head. Dang Dai Yi Xue, 2012, 8: 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zhao D, Xu D, Wang W, Cui X. Iliac graft vascularization for femoral head osteonecrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2006, 442: 171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Zhao D, Wang B, Guo L, Yang L, Tian F. Will a vascularized greater trochanter graft preserve the necrotic femoral head?. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2010, 468: 1316–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wang BJ, Zhao DW, Guo L, et al. Clinical outcome of vascularized iliac bone flap transplantation for bilateral osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Zhongguo Gu Yu Guan Jie Wai Ke, 2014, 7: 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Zhao D, Xiaobing Y, Wang T, et al. Digital subtraction angiography in selection of the vascularized greater trochanter bone grafting for treatment of osteonecrosis of femoral head. Microsurgery, 2013, 33: 656–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wang B, Zhao D, Liu B, Wang W. Treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head by using the greater trochanteric bone flap with double vascular pedicles. Microsurgery, 2013, 33: 593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Zhao D, Cui D, Lu F, et al. Combined vascularized iliac and greater trochanter graftings for reconstruction of the osteonecrosis femoral head with collapse: reports of three cases with 20 years follow‐up. Microsurgery, 2012, 32: 546–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zhao D, Zhang Y, Wang W, et al. Tantalum rod implantation and vascularized iliac grafting for osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Orthopedics, 2013, 36: 789–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Zhao D, Liu B, Wang B, et al. Autologous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells associated with tantalum rod implantation and vascularized iliac grafting for the treatment of end‐stage osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Biomed Res Int, 2015, 2015: 240506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Xue F, Zhang CQ, Chai LZ, Chen SB, Ding L. Free vascularized fibular grafting for osteonecrosis of femoral head: a systemic review. Zhongguo Gu Yu Guan Jie Sun Shang Za Zhi, 2014, 29: 322–324 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 81. Wang GM, Zhang CQ, Ding H, Chen SB. Patients with necrosis of the femoral head and taking hormone for a long time after fibular graft: eight hips receiving total hip replacement. Zhongguo Zu Zhi Gong Cheng Yan Jiu, 2014, 18: 8547–8552 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 82. Tian L, Wang KZ, Dang XQ, Wang CS. Long‐term effects of vascularized fibular graft transplantation for avascular necrosis of femoral head. Zhonghua Guan Jie Wai Ke Za Zhi Dian Zi Ban, 2012, 6: 34–38 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 83. Nakasone S, Takao M, Sakai T, Nishii T, Sugano N. Does the extent of osteonecrosis affect the survival of hip resurfacing?. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2013, 471: 1926–1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Issa K, Johnson AJ, Naziri Q, Khanuja HS, Delanois RE, Mont MA. Hip osteonecrosis: does prior hip surgery alter outcomes co to an initial primary total hip arthroplasty?. J Arthroplasty, 2014, 29: 162–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Li J, He C, Li D, Zheng W, Liu D, Xu W. Early failure of the Durom prosthesis in metal‐on‐metal hip resurfacing in Chinese patients. J Arthroplasty, 2013, 28: 1816–1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Mont MA. CORR insights®: does the extent of osteonecrosis affect the survival of hip resurfacing?. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2013, 471: 1935–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Bedard NA, Callaghan JJ, Liu SS, Greiner JJ, Klaassen AL, Johnston RC. Cementless THA for the treatment of osteonecrosis at 10‐year follow‐up: have we improved compared to cemented THA?. J Arthroplasty, 2013, 28: 1192–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Bergh C, Fenstad AM, Furnes O, et al. Increased risk of revision in patients with non‐traumatic femoral head necrosis. Acta Orthop, 2014, 85: 11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Nam KW, Kim YL, Yoo JJ, et al. Fate of untreated asymptomatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2008, 90: 477–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Helbig L, Simank HG, Kroeber M, Schmidmaier G, Grützner PA, Guehring T. Core decompression combined with implantation of a demineralised bone matrix for non‐traumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg, 2012, 132: 1095–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Rajagopal M, Balch Samora J, Ellis TJ. Efficacy of core decompression as treatment for osteonecrosis of the hip: a systematic review. Hip Int, 2012, 22: 489–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Zhang TY, Zhao DW, Wang ZL, et al. Core decompression treatment of ischaemia and venous congestion caused femoral head necrosis of curative effect observation in canine. Shan Dong Yi Yao, 2014, 54: 32–34 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 93. Sun W, Li ZR, Gao FQ, et al. Porous bioceramic beta‐tricalcium phosphate for treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Zhongguo Zu Zhi Gong Cheng Yan Jiu, 2014, 18: 2474–2479 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 94. Liu B, Wei S, Yue D, Guo W. Combined tantalum implant with bone grafting for the treatment of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J Invest Surg, 2013, 26: 158–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Liu ZH, Guo WS, Li ZR, et al. Porous tantalum rods for treating osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Genet Mol Res, 2014, 13: 8342–8352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Chen ZW, Chen WH, Wang RT, et al. Proposal on bringing WOMAC and holistic health evaluation scale into outcome evaluation of hip protection therapy for ANFH. Shi Jie Zhong Yi Yao, 2014, 9: 517–519. [Google Scholar]

- 97. Kisner C, Colby LA. The hip In: Kisner C, Colby LA, eds. Therapeutic Exercise: Foundations and Techniques, 5th edn. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company, 2007; 643–687. [Google Scholar]

- 98. Zeng ZH, Yu AX, Yu GR, et al. Postoperative rehabilitation treatment in ONFH. Zhonghua Wu Li Yi Xue Yu Kang Fu Za Zhi, 2005, 27: 557–558 (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]