Abstract

Objective

Acute hematogenous infection is a devastating complication that can occur after total knee arthroplasty (TKA). The best strategies for management of this infection remain controversial. Two‐stage revision has been well described as the gold standard for the management of chronic late infections. However, there is a paucity of information presently available on the management and outcomes of patients treated for acute hematogenous infections. The purpose of the present study was to report the outcome of acute hematogenous infections following TKA with the treatment of irrigation, debridement, and retention of the prosthetic components.

Methods

Eleven patients who had been diagnosed with acute hematogenous infection of the knee following TKA underwent irrigation and debridement between 2002 and 2012. To improve the efficiency of irrigation, a vacuum constriction device was used and the most sensitive antibiotics were injected into the irrigation saline. The mean age of the 11 patients was 56.3 ± 11.8 years (range, 35–73 years), with 2 male patients (18.2%) and 9 female patients (81.8%). The diagnosis at primary operation was osteoarthritis in three cases, rheumatoid arthritis in seven and osteoarthritis (OA) secondary to fracture in 1. They had pain and swell with the acute onset of pain after a previously well‐functioning TKA, and met the Musculoskeletal Infection Society (MSIS) criteria for prosthetic joint infection. Before the onset of symptoms in the operated knees, patients had a history of bacteriaemia, and blood culture was consistent with the culture result of local infection. Failure was defined as: (i) death before the end of antibiotic treatment; (ii) a further surgical intervention for treatment of infection was needed; and (iii) life‐long antibiotic treatment, or chronic infection. The prosthesis survivorship, Knee Society Score (KSS) and the factors that may lead to the infection recurrence, such as type of bacteria, age, sex, rheumatoid arthritis, history of diabetes, and interval surgery time, were analyzed.

Results

Among the 11 patients, the most common infecting organisms were staphylococcal and streptococcus species. The 2 staphylococcal species cases included: Staphylococcus epidermidis (1) and Staphylococcus aureus (1); The 7 S treptococcus species cases included: Streptococcus agalactiae (1), β‐ H emolytic S treptococcus (1), S treptococcus pneumonia (3), S treptococcus dysgalactiae (1), V iridans streptococci (1) and Enterobacter cloacae (1). The survivorship at the endpoint was 9 in 2 years. The survival rate for patients with a staphylococcal infection was 0%, and 100% for patients infected with non‐staphylococcus species, with a mean KSS of 72.6 points. The duration of symptoms prior to operation and the type of pathogen affected the outcome (P = 0.00).

Conclusions

Patients who developed an acute hematogenous infection with non‐staphylococcus species following operative debridement and continuous irrigation with prosthetic retention had satisfactory outcomes, but patients infected with staphylococcal had poor results. To improve the success rate of treatment, patients should be treated as soon as possible and individually according to the bacterial culture results.

Keywords: Continuous irrigation, Debridement, Hematogenous infection, Total knee arthroplasty

Introduction

Infection is rare but is also one of the most devastating complications following total knee arthroplasty (TKA), occurring in 1%–2% of primary cases1. As the number of TKAs performed has increased rapidly over the past 10 years, the number of infections and the economic burden to the health‐care system have also been grown.

In the published literature, prosthetic joint infections (PJI) are classified into three categories (early, delayed, or late), according to the infection occurrence after insertion of the prosthesis, and this classification can help determine pathogenesis and appropriate management2. Acute hematogenous infection is rare in the early PJIs that occur in patients after TKA.

Despite a great amount of basic and clinical research in this field, the strategies to manage these infections remain controversial. Two‐stage revision has been well described as the gold standard for the management of chronic late infections3, 4. However, there is a paucity of information presently available on the management and outcomes of patients treated for early PJI.

Joint irrigation and debridement surgery is a procedure commonly performed in cases of early postoperative prosthetic joint infections5, 6, 7, 8, 9. Some prior studies on this procedure with only a small number of patients report that irrigation and debridement with retention of components is a low‐morbidity, low‐cost treatment5, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14. This surgery is a less traumatic procedure compared to two‐stage revision and, hence, is attractive for both surgeons and the patients. It is reported to achieve much more favorable outcomes in treating acute prosthetic joint infections only if pursued early after the onset of infection. It is not supported for chronic infection. Although the exact timing for this interval is not sure, most studies report a higher failure rate if this procedure is undertaken after 2–6 weeks after onset of infection. Therefore, most surgeons will no attempt irrigation and debridement of an infected prosthesis if the infection has been ongoing for more than 6 weeks5, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14.

The failure rate of this procedure is high, with an average of 68% provided in the published literature (61%–82%15). However, a few studies describe eradication of prosthetic joint infection by debridement in 70%–90% of their study population9, 16. In contrast, the treatment result of this procedure in several other reports was generally poor, with an overall infection recurrence rate of approximately 50%–80% for hips8, 17 and 70% for knees18, 19.

The difference in results could be attributed partly to the multiplicity of variables that potentially influence the success of the surgery. Although some of the poor prognostic factors have previously been identified, there is substantial controversy in the literature regarding the relative significance of those factors. The exact duration of symptoms after which prosthesis retention is less likely to result in infection curation varies from 2 days to 4 weeks18.

Host factors such as diabetes mellitus and rheumatoid arthritis and bacterial species such as Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic joint infections managed with debridement and prosthesis retention are associated with a high rate of infection recurrence in some reports14. Little data is available to support this recommendation.

In the management of periprosthetic joint infections, sensitivity of antibiotics and bactericidal levels of intraarticular (i.a.) antibiotics are key points. However, it is difficult to achieve high enough levels of antibiotics in infected total joint arthroplasty intravenously. Intra‐articular local delivery of antibiotics has been demonstrated to be effective in several studies20. Whiteside reports that i.a. delivery of antibiotics produced peak concentrations many orders of magnitude higher than achieved with i.v. administration, and levels of antibiotics that remained therapeutic for 24 h, with therapeutic levels also achieved in the serum. This was in contrast to the synovial fluid levels achieved from i.v. dosing, which were proved to become subtherapeutic in the knee after 6 h. Intra‐articular administration was shown to maintain the concentration of antibiotics in the knee joint cavity above minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) for at least 24 h following administration21. High antibiotic concentrations in the synovial fluid have a distinct advantage in treating infections involving a metal implant. This factor is especially important before bacteria have formed a glycocalyx on implant surfaces22. Because the formation of small colony variants with long reproductive intervals contributes to antibiotic resistance in treatment23, 24, it seems likely that the sustained high concentration of antibiotics that is achieved with continuous i.a. injection will be important in the effective management of metallic implant infections.

The purpose of this study was to demonstrate the outcome of acute hematogenous infections following TKA with the treatment of irrigation, debridement, and exchange of the liner and retention of the prosthetic components. To improve the outcome of components retention therapy, we used new techniques in the continuous irrigation, including: (i) irrigation combined with a vacuum constriction device to reduce the incidence of pipe blocks and to improve the efficiency of irrigation; (ii) injection with the most sensitive antibiotics guided by the result of organism culture to the irrigation saline; and (iii) maintenance of the antibiotics concentration in irrigation saline five times that of the MIC necessary to kill the bacteria around the prosthesis after the debridement. We also intended to determine the effects of the timing of debridement, bacterial species, and intravenous combined with local usage of antibiotics.

Materials and Methods

Patient Selection

We undertook a retrospective study of 11 patients who received treatment for an acute hematogenous infection after primary TKA during the years of 2002–2012. All the data were collected from our institutional data repository. Inclusion criteria required that: (i) patients had pain and swell with acute onset of pain after a previously well‐functioning TKA, and met the Musculoskeletal Infection Society (MSIS) criteria for prosthetic joint infection25; (ii) patients had a minimum of 6 months from their index TKA without a history of peri‐operative infection or wound healing problems (the inclusion of acute post‐operative or chronic infections was avoided)26; (iii) patients’ prosthetic components were well‐fixed and confirmed intra‐operatively and by consecutive radiographies; and (iv) before the onset of symptoms in the operated knees, patients had a history of bacteremia, and blood culture was consistent with the culture result of local infection. This study was approved by our institutional review board and ethics committee.

Demographics

The mean age of the 11 patients was 56.3 ± 11.8 years (range, 35–73 years), including 2 men (18.2%) and 9 women (81.8%). The diagnosis at primary operation was osteoarthritis (OA) in 3 cases, rheumatoid arthritis in 7, and OA secondary to fracture in 1.

Two of the 11 patients had a history of diabetes mellitus (18.2%). Among the patients, 7 had a history of rheumatoid arthritis (63.6%), and 4 of these 7 patients had hypoadrenocorticism (36.3%). The mean duration of symptoms prior to operative intervention was 4.7 ± 1.7 days (range, 2–7 days). Among the 11 patients, 5 underwent surgery within 4 days of the onset of symptoms (45.5%). The mean interval between the performance of the index arthroplasty and the treatment of the acute hematogenous infection was 17.1 ± 15.7 months (range, 7–61 months).

Symptoms and Laboratory Data

Five patients had a history of upper respiratory tract infection, 1 cellulitis, 1 hepatapostema in acute pancreatitis, 1 gingivitis, 1 diabetic foot ulcers, and 1 urinary system infection before the onset of symptoms in the operated knees. Blood culture was positive in 6 of the 11 patients, which was consistent with the culture result of local infection both in the sites infected previously and in the knees. The knee prostheses were Nexgen (Zimmer, USA). The fixation of the primary prosthesis was with cement. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was elevated in all patients, with a mean value of 89.5 ± 38.8 mm/1 h (range, 27–149 mm/1 h). The same rising tendency occurred for the C‐reactive protein (CRP) level, with a mean value of 22.1 ± 7.4 mg/L (range, 14–40 mg/L) and procalcitonin with a mean value of 1.72 ± 1.25 ng/mL (range, 0.27–4.20 mg/L).

Surgery Technique

All 11 patients were treated with emergency surgery as soon as possible after the onset of symptoms. The mean duration of symptoms prior to operative intervention was 4.7 ± 1.7 days (range, 2–7 days). Among the 11 patients, 5 underwent surgery within 4 days of the onset of symptoms (45.5%).

Debridement

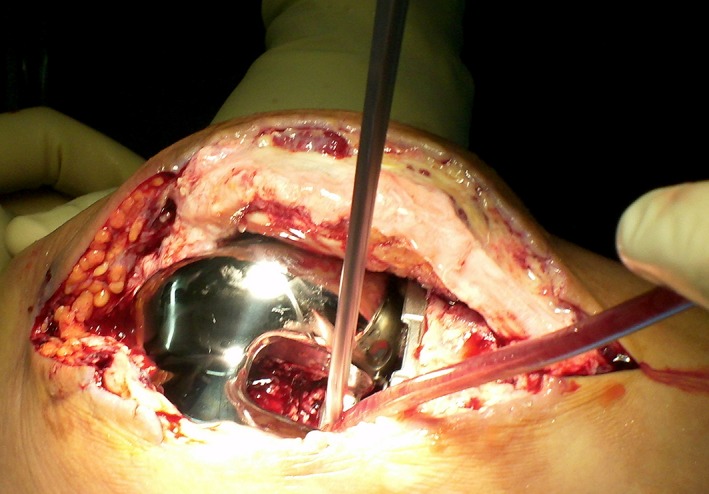

All 11 patients who presented with an acute hematogenous infection at our institution were treated with urgent debridement. The skin incision was the same as for the previous operation. Joint fluid was collected with a syringe as the capsule was incised. A synovectomy and thorough debridement were carried out (Fig. 1). Debridement of the posterior region was performed after removal of the polyethylene liner (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

In the operation, all the infected synovium and tissues in the knee were debrided thoroughly.

Figure 2.

Debridement of the posterior region was performed after the removal of polyethylene liner.

Typically, the samples of synovium from two or three sites that appeared to be inflamed and edematous macroscopically in the joint cavity were sent to culture bacteria27, 28. These samples were collected before application of antibiotics or lavage with aqueous chlorhexidine.

A pulsatile washer was used in the operation. We used 10‐L saline to wash the articular cavity (Fig. 3). We then soaked the surface of the knee with 0.5 L 0.025% chlorhexidine for approximately 5 min. Before inserting a new polyethylene liner, we scrubbed the surface of the tibia and femoral components carefully using gauze to remove the biofilm tissue.

Figure 3.

Pulsatile washer and 10‐L saline were used to wash the articular cavity after debridement.

New Irrigation Device

We placed a tube in the intercondylar fossa and sutured it on the fat pad to prevent shifting. In the continuous irrigation, patients were in the supine position with the tube positioned in the lower part of the joint cavity so that it could produce water flow to wash both the blood clot and necrotic tissue out of the joint cavity. Two‐way draining devices for outlets were placed at the suprapatellaris bursa and medial tibial tubercle, which led the drainage in two directions (up and down, Fig. 4). Using the two‐way outlet can improve the efficiency of irrigation; meanwhile it can promote the circulation formed in the whole joint cavity and make fluids flow through each part of the joint cavity in irrigation. An optimized vacuum sealing drainage device (VSD, Braun, Germany) was applied with a porous sponge placed at the outlet to replace the traditional drainage tube. To ensure the same pressure in two directions, the two VSD devices were linked by the same vacuum connection. The suction pressure was set at 15 cm H2O. The incision was sealed by Safetac (Molnlycke, Sweden) to keep the skin dry and ensure that the incision could heal quickly.

Figure 4.

Two‐way draining devices for outlet were placed at the suprapatellaris bursa and medial tibial tubercle, and the drainage led in two directions (up and down).

Continuous Closed Irrigation

Continuous closed irrigation was performed at the moment when the tourniquet was released. Before we gained the synovium culture results, we used plenty of saline (approximately 30–50,000 mL/day), lavaging continuously to wash out all the sludged blood and necrosis tissue, which comprised the culture medium for the bacteria (Fig. 5). The local antibiotics therapy was commenced as soon as the culture results and the sensitivity tests were available. We chose antibiotics with minimal bactericidal concentration (Table 1), and injected them into the saline to ensure the concentration was five times the minimal bactericidal concentration, and slowed down the liquid flow rate to increase the infiltrate degree and duration of antibiotics in the joint cavity. The duration of the irrigation lasted 8.1 ± 3.9 days (range, 3–15 days) until the values of the ESR and CRP started falling with negative bacteria culture from the blood sample.

Figure 5.

Black arrow point the 2 tubes input the fluid; Red arrow point the 2 tube for drainage. Continuous closed irrigation was performed, approximately 30–50 000 mL/day lavaging continuously to wash out all the sludged blood and necrosis tissue.

Table 1.

Types of bacteria and the management of antibiotics concentration

| Number | Bacteria | Antibiotics | MIC (μg/mL) | Concentration in irrigation (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | Levofloxacin | 1 | 5 |

| 2 | Staphylococcus aureus | Gentamicin | 4 | 20 |

| 3 | Streptococcus agalactiae | Chloramphenicol | 8 | 40 |

| 4 | β‐Hemolytic Streptococcus | Ampicilin | 0.25 | 1.25 |

| 5 | Streptococcus pneumoniae | Clindamycin | 0.25 | 1.25 |

| 6 | Streptococcus dysgalactiae | Levofloxacin | 2 | 10 |

| 7 | Viridans streptococci | Erythromycin | 0.25 | 1.25 |

| 8 | Enterobacter cloacae | Levofloxacin | 2 | 10 |

| 9 | Streptococcus pneumoniae | Levofloxacin | 2 | 10 |

| 10 | Streptococcus pneumoniae | Erythromycin | 0.25 | 1.25 |

| 11 | Escherichia coli | Levofloxacin | 4 | 20 |

MIC, minimal inhibitory concentration.

Systemic Antibiotics Application

Systemic antibiotics were not used prior to surgery to increase the positive rate of bacteria culture. After the surgery, patients were given i.v. vancomycin and meropenem before the culture results were available. Meropenem was discontinued 48 h post‐surgery if gram‐negative organisms had not been isolated. The appropriate i.v. antibiotic therapy was guided by the culture results and sensitivity tests. Patients subsequently received 6 weeks of organism‐specific i.v. antibiotics, followed by a course of oral antibiotics for 3 months postoperatively29, 30, 31, 32, 33.

Statistical Analysis

Patients’ follow‐up time lasted for a minimum of 2 years, or until the recurrence of infection. Failure was defined if a further surgical intervention for treatment of infection was needed. Patients were followed clinically using the Knee Society Score (KSS)34. Radiographs were evaluated to identify whether there was evidence of prosthetic loosening. Data were analyzed using SPSS software (SPSS 17.0, IBM, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study population. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed to estimate the failure‐free survival based on the need for further surgical intervention for treatment of infection as the endpoint. The log‐rank test was utilized to determine the effects of patient age, sex, the number of days between surgery and the onset of symptoms, type of infecting organism (staphylococcus compared with non‐staphylococcus), and the presence of diabetes, inflammatory arthritis or any immunocompromising disorder on failure free survival. A 0.05 significance level was used for all statistical tests.

Results

Intraoperative Findings

In all cases, the joint fluid looked like pus with necrolysis synovium. The synovium appeared to be inflamed and edematous. After synovectomy, continuous irrigation was performed. At the beginning of continuous closed irrigation, the appearance of the fluid was pale and bloody; 6–8 h later, the fluid became clear. The pieces of soft tissue were washed out intermittently. The irrigation lasted until negative bacteria culture from the blood sample.

Bacterial Culture

The most common infecting organisms were staphylococcal and streptococcus species. The 2 staphylococcal species cases included: Staphylococcus epidermidis (1) and Staphylococcus aureus (1). The 7 streptococcus species cases included: Streptococcus agalactiae (1), β‐Hemolytic streptococcus (1), Streptococcus pneumonia (3), Streptococcus dysgalactiae (1), Viridans streptococci (1), and Enterobacter cloacae (1).

Survivorship

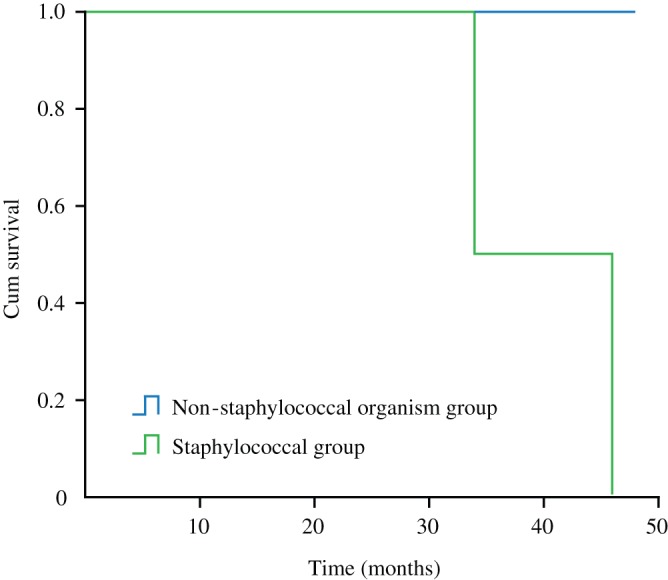

Recurrent infection developed in 2 of the 11 joints. Recurrence of infection developed in 4 months on average postoperatively (range, 2–6 months). In both patients, implants were removed in an attempt to eradicate the infection; both patients underwent a two‐stage exchange and 1 of the patients required a second implant removal prior to a second revision in the same knee. Thus, of the 2 recurrent infections, only 1 patient underwent a successful two‐stage exchange. The 2 patients were recurrently infected with Staphylococcus species.

Survivorship of the prosthesis was 9 of 11 Patients (81.8%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 81.1%–82.5%) in 2‐year follow‐up time for all patients (Fig. 6): 0% for patients with a staphylococcal infection and 100% for patients infected with an organism other than staphylococcus species (Figs 7, 8).

Figure 6.

Survivorship curve of recurrent infection at the endpoint.

Figure 7.

Survivorship curves, showing survivorship of patients infected with a staphylococcal (group 2) as opposed to a non‐staphylococcal organism (group 1).

Figure 8.

A female patient, 56 years old, with rheumatoid arthritis, was infected with S treptococcus agalactiae 6 months after primary TKA. Debridement and continuous irrigation were performed on 20 September 2012. (A) Preoperative X‐ray showed there was no radiolucency exist; (B) 3 months postoperation, no radiolucency was found in anteroposterior and lateral knee radiographs; (C) 6 months postoperation, the component was still stable; (D) 6 months postoperation, there was no clearance between cement and bone; (E) until 1‐year postoperation, there was no radiolucency; and (F) at 2‐year follow‐up, the retained prosthesis showed no radiographic evidence of implant loosening.

In the patients available for study, the log‐rank test showed that there was no difference in failure based on patient age (P = 0.192), sex (P = 0.35), history of rheumatoid arthritis (P = 0.35), or history of diabetes mellitus (P = 0.545). There was obvious difference in failure based on duration of symptoms prior to surgery (P = 0.00).

The 9 patients that retained their implants and were alive were followed for a mean of 60.2 ± 22.6 months (range, 26–98 months). The mean KSS at the most recent evaluation was 72.6 points (range, 51–86 points) for the patients. None of the patients with a retained prosthesis showed radiographic evidence of implant loosening. The ESR was elevated in all patients at the final follow‐up, with a mean value of 10.1 ± 5.9 mm/1 h (range, 2–22 mm/1 h). The CRP mean value was 5.5 ± 2.7 mg/L (range, 2.5–9.5 mg/L).

Discussion

Prosthetic joint infection is a clinically important problem even though its incidence is low35, 36. The gold standard for chronic infection treatment is the two‐stage revision that includes interval use of antibiotic‐loaded cement spacers32, 33, i.v. antibiotics, and the use of antibiotic‐loaded cement for prosthesis fixation at reimplantation, which results in infection‐free survival rates of 80%–100%37, 38. However, we believed that acute hematogenous infection is different from chronic infection. For a functional prosthetic joint without evidence of loosening, the treatment strategy is different from that for chronic prosthetic infections. Retention of the prosthetic components should be the target of treatment33, 39.

A high rate of failure is associated with the retention of components for the treatment of an infected TKA, as reported in most studies12, 19, 40, 41. Those studies that have been published provide limited details on the antibiotic sensitivities of the isolated organisms as well as the presence of, for example, sinus tracts, so we were unable to refer to the literature alone. To improve the success rate with debridement, washout and prosthesis retention, factors to consider include bacterial virulence, host quality, thoroughness of debridement and effectiveness of continuous irrigation.

With the patients available in this study, our analysis suggested that the only factor that was predictive of failure was infection with a staphylococcal organism. Similarly, Deirmengian et al. 14 report a high failure rate with component retention in the setting of an acute infection following TKA with a gram‐positive organism, with a failure rate of 65%, although the results were not reported separately for acute postoperative as opposed to acute hematogenous infections. The relatively poor results for staphylococcal infections were possible due to biofilm production and associated with antibiotic resistance10, 13, 42, 43. Unfortunately, antibiotic therapy is normally chosen according to conventional susceptibility testing, which may be inadequate in the setting of biofilm44. Our understanding of this particular challenge can be enhanced if there will not be further biofilm, which can make the treatment more effective. It is not sufficient to scratch the component’s surface in debridement and local antibiotics when washing out.

However, in the patients other than those infected with staphylococcus species, survivorship of the prosthesis was 100%. In these cases, the large amount of irrigation saline can decrease the blood block and necrosis tissue. We insisted that irrigation must be performed as soon as the release of the tourniquet to avoid the formation of blood sludge. In addition, we optimized the drainage device as the drainage tube block was the key reason for failure: as the water pressure increased, the saline would flow out from the cavity through the incision. The bacteria adhered to the skin could flow into the joint cavity through the incision. An acute hematogenous infection would become a multiple organism infection, especially for the methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus, which is a common pathogeny of hospital‐acquired infections. Therefore, the tube was substituted by the vacuum sealing drainage device to avoid being blocked. We believed that quick healing of the incision was key. Therefore, smooth flowing of the irrigation saline and a dry incision were necessary.

It is common to apply local antibiotics to treat infection after total knee arthroplasty, with the antibiotics mixed into a polymethymethacrylate (PMMA) spacer or PMMA bead chains. Nelson compared the local antibiotic therapy by PMMA gentamicin and systemic antibiotics. The results demonstrated an absolute 18% risk reduction42. Successful retention of the prosthetic components requires that the concentration of antibiotics should be higher than the MIC in the infected joints. Thus, it is questionable whether bactericidal concentration was achieved for these antimicrobial drugs in systemic antibiotics. The penetration of an antibiotic into an infected joint mainly depends on its pharmacological characteristics. Ketterl and Wittwer reported that bone tissue concentration of systemically applied vancomycin did not exceed 14.5% of the serum load45. It is reported that concentrations below the minimal inhibitory concentrations would induce the production of multiple‐resistant bacteria46, 47, which results in failure of therapy. Considering the serum‐bone ratios of the different kinds of antimicrobial drugs, we thought that combining local with systemics antibiotics could contribute to reduce the recurrence of infection. Local antibiotics can improve the effective drug concentration in the joint cavity. With continuous irrigation and recycling, the antibiotics can be well distributed into each part of the joint cavity with the fluids. In that case, it would be effective in antisepticising for infected remnants after the debridement.

The present study has two limitations. First, it includes a relatively small number of patients and it is a retrospective review. As we used strict criteria for inclusion of patients in the study, we excluded some chronic infections. Hence, only 11 patients were included in the study. However, the treatment with local antibiotics postoperatively varied; therefore, it was unclear from our work what the appropriate length of local antibiotic treatment should be.

Conclusions

There were not enough patients for us to reveal more differences in failure rates depending on the infecting bacteria. We were unable to demonstrate that component retention reached a reasonable result for the acute hematogenous infection, although 2 cases developed recurrent infection and eventually required further surgery. Patients should be treated individually according to their different clinical circumstances. For patients who are infected with non‐staphylococcus species, prosthetic retention can be successful with the debridement–irrigation procedure. It does not work well in those infected with staphylococcus species. If the organisms are identified as staphylococcus prior to surgery, the treatment can be a two‐stage resection and reimplantation rather than irrigation and debridement.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Liu Yang and Dian‐ming Jiang who have performed all the surgery; Lin Guo: Acquisition of data; Hao Chen: analysis and interpretation of data; Ying Zhang revising the article.

Disclosure: All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest with any organization that sponsored the research.

Contributor Information

Liu Yang, Email: abba315@163.com, Email: jointsurgery@163.com.

Dian‐ming Jiang, Email: jdm1026@126.com.

References

- 1. Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozic KJ, Berry D, Parvizi J. Prosthetic joint infection risk after TKA in the Medicare population. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2010, 468: 52–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aboltins C, Daffy J, Choong P, Stanley P. Current concepts in the management of prosthetic joint infection. Intern Med J, 2014, 44: 834–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cuckler JM. The infected total knee. J Arthroplasty, 2005, 20 (Suppl. 2): 33–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fehring TK, Odum S, Calton TF, Mason JB. Articulating versus static spacers in revision total knee arthroplasty for sepsis. The Ranawat Award. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2000, 380: 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hartman MB, Fehring TK, Jordan L, Norton HJ. Periprosthetic knee sepsis. The role of irrigation and debridement. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1991, 273: 113–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mont MA, Waldman B, Banerjee C, Pacheco IH, Hungerford DS. Multiple irrigation, debridement, and retention of components in infected total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty, 1997, 12: 426–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burger RR, Basch T, Hopson CN. Implant salvage in infected total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1991, 273: 105–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Crockarell JR, Hanssen AD, Osmon DR, Morrey BF. Treatment of infection with debridement and retention of the components following hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1998, 80: 1306–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Meehan AM, Osmon DR, Duffy MC, Hanssen AD, Keating MR. Outcome of penicillin‐susceptible streptococcal prosthetic joint infection treated with debridement and retention of the prosthesis. Clin Infect Dis, 2003, 36: 845–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bradbury T, Fehring TK, Taunton M, et al. The fate of acute methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus periprosthetic knee infections treated by open debridement and retention of components. J Arthroplasty, 2009, 24 (Suppl. 6): 101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Trampuz A, Zimmerli W. Prosthetic joint infections: update in diagnosis and treatment. Swiss Med Wkly, 2005, 135: 243–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Deirmengian C, Greenbaum J, Stern J. Open debridement of acute gram‐positive infections after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2003, 416: 129–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marculescu CE, Berbari EF, Hanssen AD, et al. Outcome of prosthetic joint infections treated with debridement and retention of components. Clin Infect Dis, 2006, 42: 471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Deirmengian C, Greenbaum J, Lotke PA, Booth RE Jr, Lonner JH. Limited success with open debridement and retention of components in the treatment of acute Staphylococcus aureus infections after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty, 2003, 18 (Suppl. 1): 22–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sherrell JC, Fehring TK, Odum S. The Chitranjan Ranawat Award: fate of two‐stage reimplantation after failed irrigation and débridement for periprosthetic knee infection. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2011, 469: 18–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aboltins CA, Page MA, Buising KL, et al. Treatment of staphylococcal prosthetic joint infections with debridement, prosthesis retention and oral rifampicin and fusidic acid. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2007, 13: 586–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brandt CM, Sistrunk WW, Duffy MC, et al. Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic joint infection treated with debridement and prosthesis retention. Clin Infect Dis, 1997, 24: 914–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Silva M, Tharani R, Schmalzried TP. Results of direct exchange or debridement of the infected total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2002, 404: 125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rand JA. Alternatives to reimplantation for salvage of the total knee arthroplasty complicated by infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1993, 75: 282–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Perry CR, Hulsey RE, Mann FA, Miller GA, Pearson RL. Treatment of acutely infected arthroplasties with incision, drainage, and local antibiotics delivered via an implantable pump. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1992, 281: 216–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Whiteside LA, Roy ME, Nayfeh TA. Intra‐articular infusion a direct approach to treatment of infected total knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J, 2016, 98 (Suppl. A): 31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wymenga AB, Van Dijke BJ, Van Horn JR, Slooff TJ. Prosthesis‐related infection. Etiology, prophylaxis and diagnosis (a review). Acta Orthop Belg, 1990, 56: 463–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rusthoven JJ, Davies TA, Lerner SA. Clinical isolation and characterization of aminoglycoside‐resistant small colony variants of Enterobacter aerogenes. Am J Med, 1979, 67: 702–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Neut D, Hendriks JG, van Horn JR, van der Mei HC, Busscher HJ. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation and slime excretion on antibiotic‐loaded bone cement. Acta Orthop, 2005, 76: 109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Workgroup Convened by the Musculoskeletal Infection Society . New definition for periprosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplasty, 2011, 26: 1136–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Konigsberg BS, Della Valle CJ. Acute hematogenous infection following total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty, 2014, 29: 469–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Atkins BL, Athanasou N, Deeks JJ, et al. Prospective evaluation of criteria for microbiological diagnosis of prosthetic‐joint infection at revision arthroplasty. The OSIRIS Collaborative Study Group. J Clin Microbiol, 1998, 36: 2932–2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Trampuz A, Piper KE, Jacobson MJ, et al. Sonication of removed hip and knee prostheses for diagnosis of infection. N Engl J Med, 2007, 357: 654–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Westrich GH, Walcott‐Sapp S, Bornstein LJ, Bostrom MP, Windsor RE, Brause BD. Modern treatment of infected total knee arthroplasty with a 2‐stage reimplantation protocol. J Arthroplasty, 2010, 25: 1015–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Segawa H, Tsukayama DT, Kyle RF, Becker DA, Gustilo RB. Infection after total knee arthroplasty. A retrospective study of the treatment of eighty‐one infections. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1999, 81: 1434–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Darouiche RO. Treatment of infections associated with surgical implants. N Engl J Med, 2004, 350: 1422–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sia IG, Berbari EF, Karchmer AW. Prosthetic joint infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am, 2005, 19: 885–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Osmon DR, Berbari EF. Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis, 2013, 56: e1–e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, Scott WN. Rationale of the Knee Society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1989, 248: 13–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. Prosthetic‐joint infections. N Engl J Med, 2004, 351: 1645–1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lentino JR. Prosthetic joint infections: bane of orthopedists, challenge for infectious disease specialists. Clin Infect Dis, 2003, 36: 1157–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hart WJ, Jones RS. Two‐stage revision of infected total knee replacements using articulating cement spacers and short‐term antibiotic therapy. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 2006, 88: 1011–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hofmann AA, Goldberg T, Tanner AM, Kurtin SM. Treatment of infected total knee arthroplasty using an articulating spacer: 2–12‐year experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2005, 430: 125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Holmberg A, Thórhallsdóttir VG, Robertsson O. 75% success rate after open debridement, exchange of tibial insert, and antibiotics in knee prosthetic joint infections. Acta Orthop, 2015, 86: 457–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Waldman BJ, Hostin E, Mont MA, Hungerford DS. Infected total knee arthroplasty treated by arthroscopic irrigation and debridement. J Arthroplasty, 2000, 15: 430–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chiu FY, Chen CM. Surgical débridement and parenteral antibiotics in infected revision total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2007, 461: 130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nelson CL, Evans RP, Blaha JD, Calhoun J, Henry SL, Patzakis MJ. A comparison of gentamicin‐impregnated polymethylmethacrylate bead implantation to conventional parenteral antibiotic therapy in infected total hip and knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1993, 295: 96–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Betsch BY, Eggli S, Siebenrock KA, Tauber MG, Muhlemann K. Treatment of joint prosthesis infection in accordance with current recommendations improves outcome. Clin Infect Dis, 2008, 46: 1221–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Patel A, Calfee RP, Plante M, Fischer SA, Arcand N, Born C. Methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 2008, 90: 1401–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ketterl R, Wittwer W. Possibilities for the use of the basic cephalosporin cefuroxime in bone surgery. Tissue levels, effectiveness and tolerance. Infection, 1993, 21 (Suppl. 1): 21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Desplaces N, Acar JF. New quinolones in the treatment of joint and bone infections. Rev Infect Dis, 1988, 10 (Suppl. 1): 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fong IW, Ledbetter WH, Vandenbroucke AC, Simbul M, Rahm V. Ciprofloxacin concentrations in bone and muscle after oral dosing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 1986, 29: 405–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]