Abstract

Background/Objectives

The epidemiology of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) after acute pancreatitis (AP) is uncertain. We sought to determine the prevalence, progression, etiology and pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) requirements for EPI during follow-up of AP by systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

Scopus, Medline and Embase were searched for prospective observational studies or randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of PERT reporting EPI during the first admission (between the start of oral refeeding and before discharge) or follow-up (≥ 1 month of discharge) for AP in adults. EPI was diagnosed by direct and/or indirect laboratory exocrine pancreatic function tests.

Results

Quantitative data were analyzed from 370 patients studied during admission (10 studies) and 1795 patients during follow-up (39 studies). The pooled prevalence of EPI during admission was 62% (95% confidence interval: 39–82%), decreasing significantly during follow-up to 35% (27–43%; risk difference: − 0.34, − 0.53 to − 0.14). There was a two-fold increase in the prevalence of EPI with severe compared with mild AP, and it was higher in patients with pancreatic necrosis and those with an alcohol etiology. The prevalence decreased during recovery, but persisted in a third of patients. There was no statistically significant difference between EPI and new-onset pre-diabetes/diabetes (risk difference: 0.8, 0.7–1.1, P = 0.33) in studies reporting both. Sensitivity analysis showed fecal elastase-1 assay detected significantly fewer patients with EPI than other tests.

Conclusions

The prevalence of EPI during admission and follow-up is substantial in patients with a first attack of AP. Unanswered questions remain about the way this is managed, and further RCTs are indicated.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10620-019-05568-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Acute pancreatitis, Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy, Necrotizing pancreatitis, Severe pancreatitis

Introduction

Patients presenting with acute pancreatitis (AP) are at risk of local and systemic complications, some of which persist beyond the hospital admission [1]. This includes both endocrine and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI). Recent studies have shown that prediabetes and diabetes mellitus (DM) occur following the first attack of AP in up to 40% patients and increase over 5 years [2]; they are associated with a marked reduction in the quality of life [3, 4]. Another study found that 10% of first-attack AP patients will then develop chronic pancreatitis [5]. A recent meta-analysis [6] investigated EPI after AP, but not during hospital admission, and found that a quarter of all AP patients develop EPI during follow-up. The risk of EPI is higher when patients have alcoholic etiology, severe and necrotizing pancreatitis.

The prevalence of EPI following AP and the use of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) are variably reported in the literature. The aim of this study was to undertake a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the prevalence of EPI using formal exocrine function tests during AP hospitalization and follow-up to determine the contributing factors and time course and define strategies for PERT to treat EPI after AP.

Methods

Data Sources and Searches

This study adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) criteria [7]. Electronic databases (Scopus, Embase and Medline) were searched (IB-R, CC-S and JL-N) for relevant studies from 1 January 1946 to 31 July 2018. References from searched studies were also examined. The keywords are listed in Supplementary Methods. Two authors (WH and DdlI-G) scrutinized all identified studies independently and agreed on those for inclusion. Citations from included studies and relevant reviews were also evaluated. When there was a discrepancy, the senior authors (JED-M and RS) arbitrated.

Study Selection

Included studies fulfilled the following criteria: (1) prospective observational studies or randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of PERT that reported on EPI during the index admission (between the start of oral refeeding and before discharge) or follow-up (≥ 1 month after discharge) for AP in adults; (2) EPI diagnosed by direct and/or indirect laboratory exocrine function tests [8, 9]; (3) with multiple publications with overlapping patient groups the most recent study was included unless an earlier study had a larger sample size. Editorials, expert opinions, reviews, abstracts, case reports, letters, small sample size (< 10 patients), pre-existing EPI, population-based studies and retrospective studies were excluded.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two authors (WH and DdlI-G) independently collected data from included studies using a standardized pro forma designed by two senior authors (JED-M and RS). The data items are provided in Supplementary Methods. Three authors (XZ, NS and WC) independently scored the included studies, and two further authors (WH and DdlI-G) resolved any disagreement. The quality of observational studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale [10] with a total score ≥ 5 (up to 4 for selection, 2 for comparability and 3 for outcome) indicative of high quality; the quality of RCTs was assessed using the Jadad system [11] with a total score ≥ 3 (randomization 0 or 1; allocation concealment 0 or 1; double blinding 0, 1 or 2; recording of dropouts and/or withdrawals 0 or 1) indicative of high quality.

Outcomes of Interest

The primary outcome was the number (proportion) of patients diagnosed with EPI following development of AP during both hospitalization for the first attack of AP and follow-up. EPI was diagnosed by either direct pancreatic function tests, including the Lundh meal test, secretin-caerulein (or pancreozymin) test (SCT), amino acid consumption test (AACT), fecal chymotrypsin test or fecal elastase-1 (FE-1) test, or indirect tests including the triolein breath test, serum fluorescein-dilaurate test, serum pancreolauryl test, urinary pancreolauryl test, urinary N-benzoyl-l-tyrosyl-P-aminobenzoic acid (NBP-PABA) test, urinary d-xylose excretion test and fecal fat excretion (FFE) test. An FE-1 of 100–200 µg/g was defined as mild to moderate EPI and < 100 µg/g as severe EPI.

Secondary outcomes included symptoms of EPI [12], treatment with PERT [12], recurrence of AP [1, 13], new-onset prediabetes and/or DM [2, 14], changes in pancreatic morphology, quality of life and employment status.

Definition of AP Severity, Complications and Pancreatic Intervention

AP was classified as severe when fulfilling one or more of the following criteria: (1) the “severe” category of the original Atlanta classification (OAC) [15]; (2) the “moderately severe” and “severe” grades of the revised Atlanta classification (RAC) [16]; (3) the presence of necrosis (> 30%), pseudocyst or abscess; (4) a clinical severity score, imaging severity indices or biomarkers greater than their respective cutoff values. Other cases of AP were classified as mild. Studies were analyzed separately if they only included infected pancreatic necrosis (IPN), and IPN was defined as those with definitive diagnosis of pancreatic infection [17] and/or unresolving sterile necrosis that was treated by pancreatic necrosectomy that became infected [17, 18]. Necrosectomy included open and minimally invasive procedures, while conservative management included no procedure, percutaneous drainage or an endoscopic procedure only [19].

Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

Pooled data were expressed as prevalence with 95% confidence interval (CI). Data for two group comparisons were expressed as relative risk (RR) or risk difference (RD) with 95% CI. Stats Direct V3.1 (StatsDirect Ltd, Cheshire, UK) was used to generate forest plots of pooled data using a random effects model to deliver the most conservative estimates. Heterogeneity was evaluated using χ2. P < 0.1 was considered significant. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using I2 values with cutoffs of 25%, 50% and 75% to indicate low, moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively [20]. Meta-analyses generated the RR and RD for each comparison between two groups. For studies of EPI during the index admission and follow-up, the prevalence of EPI during the index admission was compared with EPI during follow-up between gallstone versus alcohol etiology and OAC mild versus severe AP. For all the follow-up studies, the prevalence of EPI was compared between females versus males; gallstones versus alcohol etiology; OAC mild versus severe AP; RAC mild versus moderate to severe AP; edematous versus necrotizing AP; necrosis < 50% versus necrosis ≥ 50%; necrosis in the head versus body and/or tail; conservative management versus necrosectomy. Pooled prevalence of recurrent AP, pre-diabetes and/or DM and pancreatic morphologic changes were also generated.

Subgroup analyses examined high-quality studies, studies with sample sizes ≥ 40, Western population, etiology (gallstone or alcohol) and follow-up periods (up to 12 months, > 12–36 months, > 36–60 months and > 60 months). Sensitivity analyses considered studies restricted to first AP episodes, pre-existing DM, studies with a proportion of patients undergoing pancreatic intervention for necrosis and/or infection during the index admission, direct EPI tests, indirect EPI tests, FFE test only and FE-1 test only.

Meta-regression analyses determined the impact of publication year, patient age, gender, AP etiology, disease severity, type of EPI test and study quality on the pooled prevalence estimate using Stata SE version 13 software (StataCorp LP, College Station TX, USA); P < 0.05 was considered significant. Publication bias was assessed visually by funnel plots [21] and using P values generated from the pooled prevalence of EPI during index admission and follow-up as well as by subgroups according to Begg-Mazumdar [22] and Egger et al. [23]; P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Characteristics of Included Studies

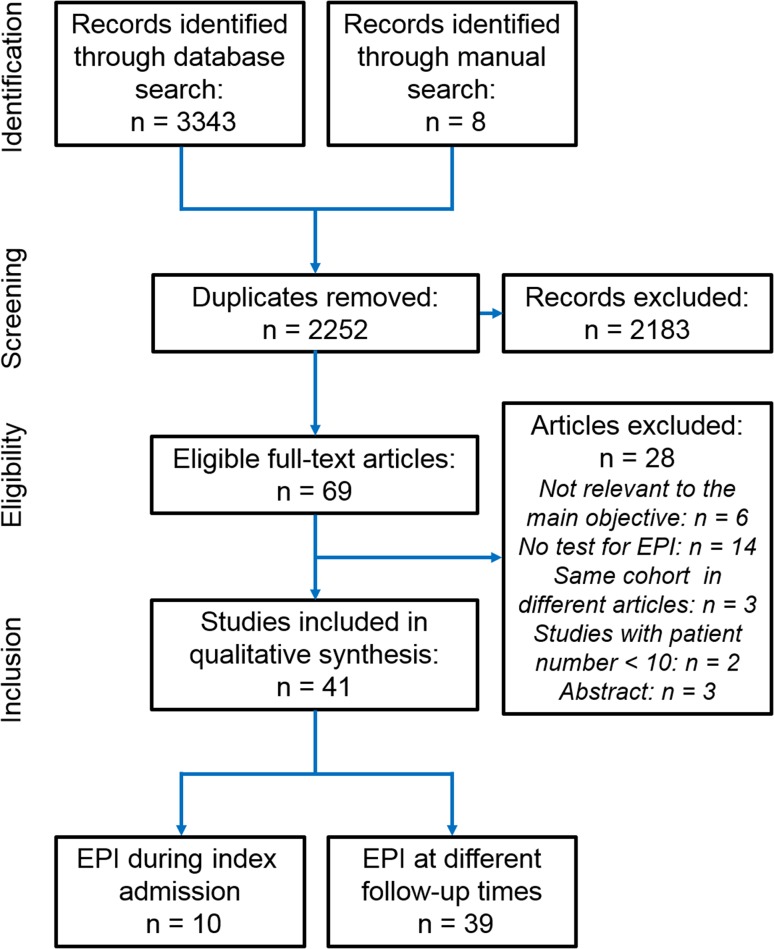

A PRISMA flow diagram for study selection is shown in Fig. 1. A final total of 41 studies [24–64] from 16 countries were included. The study designs are summarized in Table 1. Thirty-seven studies were published in English, two [27, 29] in Spanish, one [41] in Italian and one [59] in Russian. There were two RCTs [30, 55] for PERT versus placebo and one for the endoscopic versus surgical step-up approach [64]. Ten studies [36, 44, 46, 47, 49, 51, 53, 54, 57, 64] had a consecutive cohort design, and the remainders were non-consecutive cohort studies. Three studies [55, 56, 64] were multicenter. The shortest median follow-up was 1 month [27] and the longest 180 months [51]. Ten studies [25, 27, 29–31, 40, 44, 48, 49, 55] assessed EPI during hospitalization and 39 studies [24–48, 50–54, 56–64] during follow-up.

Fig. 1.

Preferred reporting items for the systematic reviews flow chart of study selection for this systematic review

Table 1.

Design and quality assessment of included studies

| Study | Year | Country | Follow-up design | Single or multicenter | Index hospitalization period of source cohort | Study AP populationa | Type of comparison | Follow-up time (months)b | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Braganza et al. | 1973 | UK | Prospective cohort | Single | NR | NR | None | > 3 | NOS, 6 |

| Seligson et al. | 1982 | Sweden | Prospective cohort | Single | 1969–1978 | Severec | None | 59 (18–108) | NOS, 5 |

| Mitchell et al. | 1983 | UK | Prospective cohort | Single | NR | All severity | Index admission versus follow-up; mild versus severe; biliary versus alcohol | Index admission, 2–12 | NOS, 6 |

| Angelini et al. | 1984 | Italy | Prospective cohort | Single | NR | Severec | Biliary versus alcohol | 13–36 | NOS, 5 |

| Arenas et al. | 1986 | Spain | Prospective cohort | Singe | NR | All severity | Index admission versus follow-up; biliary versus alcohol | Index admission, 1 | NOS, 4 |

| Büchler et al. | 1987 | Germany | Prospective cohort | Single | 1981 to 1985 | All severity | Edematous versus necrotizing; biliary versus alcohol | 2–12, 13–40 | NOS, 6 |

| Garnacho Montero et al. | 1989 | Spain | Prospective cohort | Single | NR | All severity; biliary and alcohol | Index admission versus follow-up; biliary versus alcohol | Index admission, 3–12 | NOS, 6 |

| Airely et al. | 1991 | UK | Prospective RCT | Single | NR | Mildc | Index admission versus follow-up; placebo versus PERT | Index admission, 1.5 | Jadad, 3 |

| Glasbrenner et al. | 1992 | Germany | Prospective cohort | Single | NR | Mildc | Index admission versus follow-up; biliary versus alcohol | Index admission, 1.5 | NOS, 5 |

| Bozkurt et al. | 1995 | Germany | Prospective cohort | Single | NR | IPN | None | 3–12, 18 | NOS, 5 |

| Seidensticker et al. | 1995 | Germany | Prospective cohort | Single | 1976 to 1992 | All severity | Biliary versus alcohol | < 12, 12–60, > 60 | NOS, 5 |

| Malecka-Panas et al. (a) | 1996 | Poland | Prospective cohort | Single | NR | Severec; alcohol | None | 48–84 | NOS, 4 |

| Malecka-Panas et al. (b) | 1996 | Poland | Prospective cohort | Single | NR | All severity; biliary | None | 6–12; 36–60 | NOS, 4 |

| John et al. | 1997 | South Africa | Prospective consecutive cohort | Single | NR | All severity | None | 9 (2–16) | NOS, 4 |

| Tsiotos et al. | 1998 | USA | Prospective cohort | Single | 1983 to 1995 | IPN | None | 48 (3–132) | NOS, 5 |

| Appelros et al. | 2001 | Sweden | Prospective cohort | Single | 1985 and 1994 | Severec | None | 84 (24–144) | NOS, 4 |

| Ibars et al. | 2002 | Spain | Prospective cohort | Single | July 1994 to December 1995 | All severity; biliary | Mild versus severe | 6–12 | NOS, 6 |

| Boreham et al. | 2003 | UK | Prospective cohort | Single | December 2000 to November 2001 | All severity | Index admission versus follow-up; mild versus severe | Index admission, 3 | NOS, 7 |

| Napolitano et al. | 2003 | Italy | Prospective cohort | Single | NR | Mildc; biliary | None | 48 | NOS, 7 |

| Sabater et al. | 2004 | Spain | Prospective cohort | Single | 1994 to 1998 | Severe (included a proportion of IPN)c; biliary | Conservative versus necrosectomy | 12 | NOS, 8 |

| Migliori et al. | 2004 | Italy | Prospective cohort | Single | NR | All severity; biliary and alcohol | Edematous versus necrotizing; biliary versus alcohol | 18 | NOS, 6 |

| Bavare et al. | 2004 | India | Prospective consecutive cohort | Single | January 2001 to June 2003 | IPN | Index admission versus follow-up | Index admission, 6–12, 13–18 | NOS, 5 |

| Symersky et al. | 2006 | Netherlands | Prospective cohort | Single | 1990 to 1996 | All severity; nonalcoholic | Mild versus severe | 55 (12–90) | NOS, 4 |

| Reszetow et al. | 2007 | Poland | Prospective consecutive cohort | Single | January 1993 to December 1999 | IPN; biliary and alcohol | Biliary versus alcohol; female versus male | 61 (24–96) | NOS, 5 |

| Reddy et al. | 2007 | India | Prospective consecutive cohort | Single | 1996 to 1998 | IPN | Biliary versus alcohol; female versus male | 22 (15–36) | NOS, 5 |

| Pelli et al. | 2009 | Finland | Prospective cohort | Single | January 2001 to February 2004 | All severity, alcoholic | Index admission versus follow-up; mild versus severe | Index admission, 24 | NOS, 5 |

| Pezzilli et al. | 2009 | Italy | Prospective consecutive cohort | Single | January 2006 to December 2006 | All severity | Mild versus severe; biliary versus alcohol; female versus male | Index admission | NOS, 3 |

| Gupta et al. | 2009 | India | Prospective cohort | Single | July 2005 to December 2006 (and prior to 2005) | Severe (included a proportion of IPN)c | Conservative versus necrosectomy | 31 (7–118) | NOS, 4 |

| Uomo et al. | 2010 | Italy | Prospective consecutive cohort | Single | January 1994 to December 2006 | Severec | None | 180 (156–203) | NOS, 6 |

| Andersson et al. | 2010 | Sweden | Prospective cohort | Single | 2001–2005 | All severity | Mild versus severe | 42 (36–53) | NOS, 8 |

| Xu et al. | 2012 | China | Prospective consecutive cohort | Single | 2003 to 2008 | All severity | Mild versus severe | 29 | NOS, 7 |

| Garip et al. | 2013 | Turkey | Prospective consecutive cohort | Single | March 2003 to October 2007 | All severity | Mild versus severe; edematous versus necrotizing | 32 (6–48) | NOS, 6 |

| Kahl et al. | 2014 | Germany | Prospective RCT | Multicenter | NR | All severity | Placebo versus PERT | Index admission | Jadad, 4 |

| Vujasinovic et al. | 2014 | Slovenia | Prospective cohort | Multicenter | NR | All severity | Mild versus severe (mild versus moderate versus severed); biliary versus alcohol; female versus male | 32 | NOS, 5 |

| Winter Gasparoto et al. | 2015 | Brazil | Prospective consecutive cohort | Single | January 2002 to April 2012 | Severec | None | 35 (12–90) | NOS, 4 |

| Chandrasekaran et al. | 2015 | India | Prospective cohort | Single | July 2009 to December 2010 | Severe (included a proportion of IPN)c | Conservative versus necrosectomy | 26 ± 18 | NOS, 8 |

| Ermolov et al. | 2016 | Russia | Prospective cohort | Single | 2003 to 2012 | Severe (included a proportion of IPN)c | Conservative versus necrosectomy | 102 ± 36 | NOS, 6 |

| Nikkola et al. | 2017 | Finland | Prospective cohort | Single | January 2001 to February 2005 | All severity; alcoholic | Mild versus severed | 126 (37–155) | NOS, 5 |

| Koziel et al. | 2017 | Poland | Prospective cohort | Single | 2011 and 2012 | Mild and severe | Mild versus severe (mild versus moderate to severed); biliary versus alcohol | 14 ± 4 | NOS, 8 |

| Tu et al. | 2017 | China | Prospective cohort | Single | January 2016 to April 2016 | All severity (included a proportion of IPN) | Mild versus moderate versus severed | 43 ± 4 | NOS, 5 |

| van Brunschot et al. | 2018 | Netherland | Prospective RCT | Multicenter | September 2011 to January 2015 | Infected pancreatic necrosis | Endoscopic versus surgical step up approach | 6 | Jadad, 5 |

AP acute pancreatitis, NOS Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, NR not reported, RCT randomized controlled trial, PERT pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy, IPN infected pancreatic necrosis and/or unresolving sterile necrosis that needed necrosectomy and became infected

aIncluded all etiologies if not otherwise stated

bIndex admission refers to between the start of oral refeeding and before discharge

cSevere was defined by original Atlanta classification or the authors own clinical criteria

dSevere was defined by the revised Atlanta classification

Of the 38 studies scored by the Newcastle-Ottawa scale with Selection, Comparability and Outcome compositions (Supplementary Table 1A), 32 (84%) were of high quality [24–29, 31–54, 56–62, 64]. The three RCTs [30, 55, 64] were all of high quality (Supplementary Table 1B). Regarding the Selection section, 22 (58%) studies had no “selection of the non-exposed cohort,” while 35 (92%) did not report “demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study.” In the Comparability section, 33 (87%) did not show “comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis.” In the Outcome section, ten had no “adequacy of follow-up of cohorts.”

Characteristics of Included Patients

The overall baseline characteristics of patients are shown in Table 2. For ten inpatient studies, the pooled median age was 51 years (males, 59%); etiology was 70% gallstones, 17% alcohol and 13% other causes; six studies were restricted to first AP episodes [30, 31, 40, 44, 48, 49], while four [25, 27, 29, 55] did not report. For the 39 follow-up studies, the pooled median age was 51 years (males, 63%); etiology was 55% gallstone, 28% alcohol and 17% other causes; 16 studies were restricted to first AP episodes [30–34, 39, 40, 43–46, 48, 50, 53, 57, 60], while 5 [28, 35, 38, 56, 62] were not so restricted, and the remaining 18 [24–27, 29, 36, 37, 41, 42, 47, 51, 52, 54, 58, 59, 61, 63, 64] did not report.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients in the included studies

| Study | Patients enrolled (analyzed for EPI) | Age, yeara | Male, n (%) | Biliary | Alcoholic | Others | First AP episode | Severity criteria | Severity status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Braganza et al. | 12 (12) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Seligson et al. | 10 (10) | 54 ± 12 | 8 (80) | 2 | 7 | 1 | NR | Necrotizing AP | 10 severe |

| Mitchell et al. | 30 (30) | 22–89 | 15 (50) | 13 | 6 | 11 | NR | Clinical complication | 25 mild, 5 severe |

| Angelini et al. | 27 (20)b | NR | 24 (89)b | 14b | 10b | 3b | NR | Necrotizing AP | 27 severe |

| Arenas et al. | 26 (26) | 24–82 | 9 (35) | 16 | 4 | 7 | NR | NR | NR |

| Büchler et al. | 79 (79) | 46 | 48 (61) | 28 | 37 | 14 | Partiallyc | Necrotizing AP | 27 edematous, 32 minor necrotizing, 20 major necrotizing |

| Garnacho Montero et al. | 19 (19) | 23–75 | 9 (47) | 11 | 8 | 0 | NR | NR | NR |

| Airey et al. | 59 (41) | 62 (30–82) | 19 (46) | 30 | 6 | 5 | All | Local or systemic complication | 41 mild, 0 severe |

| Glasbrenner et al. | 29 (29) | 37 (22–68) | 17 (59) | 15 | 14 | 0 | All | Pancreatic necrosis and CRP > 120 mg/l | Mean ranson score 1.6 |

| Bozkurt et al. | 89 (53)b | 21–83b | 59 (66)b | 21b | 56b | 12b | All | IPN | 53 IPN |

| Seidensticker et al. | 38 (38) | 41 ± 14 | 25 (66) | 8 | 16 | 14 | All | Ranson score > 3 | 21 ranson score ≤ 3, 4 ranson score > 3 |

| Malecka-Panas et al. (a) | 47 (47) | 44 ± 10 | 33 (70) | 47 | 0 | 0 | All | Imrie criteria 3–4 | 47 severe |

| Malecka-Panas et al. (b) | 30 (30) | 53 ± 17 | 8 (27) | 30 | 0 | 0 | Partially (70%) | Imrie criteria ≥ 3 | NR |

| John et al. | 50 (50) | 39 | 38 (76) | 5 | 42 | 3 | NR | OAC | NR |

| Tsiotos et al. | 72 (44) | 58 (20–93) | 33 (75) | 17 | 5 | 22 | NR | IPN | 44 IPN |

| Appelros et al. | 79 (26) | 60 (27–92)b | 52 (66)b | 19b | 30b | 30b | Partially (87%) | OAC | 79 severeb |

| Ibars et al. | 63 (61) | 62 ± 14b | 17 (27)b | 63b | 0b | 0b | All | OAC and area of necrosis | 45 mild, 18 severe; 6 necrosis 30–50%, 3 necrosis ≥ 50%b |

| Boreham et al. | 23 (23) | 55 (21–77) | 13 (57) | 15 | 5 | 3 | All | OAC | 16 mild, 7 severe |

| Napolitano et al. | 35 (35) | NR | NR | 35 | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | NR |

| Sabater et al. | 39 (27) | No surgery: 61 ± 14; necrosectomy: 64 ± 11 | 12 (44.4) | 27 | 0 | 0 | NR | OAC; IPN | 27 severe (11 necrosis ≥ 50%); 12 IPN, 15 sterile necrosis |

| Migliori et al. | 75 (75) | 46 (17–80) | 57 (76) | 39 | 36 | 0 | All | Necrotizing AP | 42 edematous, 33 necrotizing |

| Bavare et al. | 18 (18) | 36 (25–47) | 18 (100) | 4 | 10 | 4 | All | IPN | 18 IPN |

| Symersky et al. | 34 (34) | 53 ± 3 | 16 (47) | 26 | 0 | 8 | All | OAC | 22 mild, 12 severe |

| Reszetow et al. | 28 (28) | 48 ± 10 | 20 (71) | 10 | 18 | 0 | All | IPN | 28 IPN (26 APACHE II > 8) |

| Reddy et al. | 10 (10) | 35 (22–47) | 8 (80) | 4 | 6 | 0 | NR | IPN | IPN (5 necrosis < 50%, 4 necrosis ≥ 50%, 1 unspecified) |

| Pelli et al. | 54 (54) | 49 (25–71) | 47 (87) | 54 | 0 | 0 | All | OAC | 41 mild, 13 severe |

| Pezzilli et al. | 75 (75) | 62 (20–94) | 37 (49) | 61 | 1 | 13 | All | OAC | 60 mild, 15 severe |

| Gupta et al. | 30 (30) | 38 ± 2 | 24 (80) | 12 | 13 | 5 | All | OAC; IPN | 22 IPN, 8 sterile necrosis |

| Uomo et al. | 65 (40) | 48±18 | 17 (42.5) | 28 | 0 | 12 | NR | NR | 25 necrosis < 50%, 15 necrosis ≥ 50% |

| Andersson et al. | 40 (40) | 61 (48–68) | 16 (40) | 20 | 10 | 10 | NR | OAC | 26 mild (3 APACHE II ≥ 8), 14 severe (9 APACHE II ≥ 8) |

| Xu et al. | 65 (65) | 59 (27–82) | 33 (51) | 50 | 7 | 8 | All | OAC | Mild 27, severe 38 |

| Garip et al. | 109 (109) | 57 ± 16 | 58 (53) | 72 | 9 | 28 | NR | APACHE II ≥ 8 | 39 severe (APACHE II ≥ 8), 70 mild (APACHE II < 8); necrosis 30 |

| Kahl et al. | 56 (55) | 51 (23–81) | 34 (62) | NR | NR | NR | NR | APACHE II ≥ 4; CRP > 120 mg/L | Placebo: APACHE II 5.1 ± 3.2, CRP 172 ± 108 mg/l; PERT: APACHE II 5.3 ± 2.9, CRP 176 ± 79 mg/l |

| Vujasinovic et al. | 100 (100) | 58 ± 12 | 65 (65) | 36 | 42 | 22 | Partially (75%) | RAC | 67 mild, 15 moderate, 18 severe |

| Winter Gasparoto et al. | 16 (16) | 48 ± 13 | 9 (56) | 10 | 4 | 0 | Yes | APACHE II ≥ 8 or 12 CRP ≥ 150 mg/l | 4 APACHE II ≥ 8, 12 CRP ≥ 150 mg/l; 9 necrosis < 30%, 4 30–50%, 3 ≥ 50% |

| Chandrasekaran et al. | 35 (35) | 37 ± 10 | 30 (86) | 11 | 19 | 5 | NR | OAC; IPN | 35 severe (1 necrosis < 30%, 7 30–50%, 27 ≥ 50%; 15 APACHE II < 8, 20 APACHE II > 8); 21 IPN, 14 sterile necrosis |

| Ermolov et al. | 210 (80)b | 55 ± 13b | 144 (69)b | NR | NR | NR | NR | OAC; IPN | Severe 210b; 34 IPN |

| Nikkola et al. | 77 (45) | 48 (25–71) | 69 (90) | 45 | 0 | 0 | All | RAC | 53 mild, 20 moderate, 4 severe |

| Koziel et al. | 150 (150) | 53 ± 15 | 94 (63) | 64 | 46 | 40 | NR | RAC | 51 mild, 99 severe |

| Tu et al. | 113 (113) | 47 ± 1 | 75 (66) | 65 | 3 | 45 | Partially (83%) | RAC; IPN | 10 mild, 12 moderate, 91 severe (73 IPN) |

| van Brunschot et al. | 98 (83) | 62 ± 13 | 63 (64) | 56 (57) | 14 (14) | 28 (29) | NR | RAC | 55 moderate, 43 severe |

EPI exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, AP acute pancreatitis, NR not reported, CRP C-reactive protein, IPN infected pancreatic necrosis, OAC original Atlanta classification, APACHE Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation, PERT pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy, RAC revised Atlanta classification

aYear is expressed as mean (standardized deviation), mean (range), median (range) or range

bData are derived from original enrolled patients rather than actual analyzed patients

cIncluded two cases of chronic pancreatitis

Pancreatic Function During Admission and Follow-Up

Detailed pancreatic function data and clinical outcomes at follow-up are shown in Table 3. For the 10 inpatient studies, 1 [48] reported pre-existing DM in 8 of 54 patients (15%), 2 [40, 49] reported none, and the remaining studies [25, 27, 29–31, 44, 55] did not report; 2 [44, 49] had a proportion of patients who had undergone pancreatic interventions, 4 [25, 30, 31, 40] had none, and 4 [27, 29, 48, 55] did not report.

Table 3.

Pancreatic function at baseline and follow-up

| Study | Patients enrolled (analyzed for EPI) | Pre-existing DM (%) | Pancreatic intervention (%)a | EPI diagnostic criteria | EPI (%)b | Use of PERT | RAP (%) | New prediabetes and/or DM (%) | Pancreatic morphology changes (%) | Health status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Braganza et al. | 12 (12) | NR | 0 (0) | SCT < lower reference rangec | 1 (0.8) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Seligson et al. | 10 (10) | 1 (10) | NR | Lundh meal test < lower reference ranged | 7 (70) | 2 (20) | NR | 5 (50) | 6 (60) | NR |

| Mitchell et al. | 30 (30) | NR | 0 (0) | NBT-PABA test with urinary PABA recovery < 57% | 7/15 (47); Index admission: 30 (100) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Angelini et al. | 27 (20) | NR | 27 (100)e | SCT < lower reference rangec | 8/20 (40) | NR | NR | 12 (44)e | 13 (48)e | NR |

| Arenas et al. | 26 (26) | NR | NR | NBT-PABA test with urinary PABA recovery < 45% | 2/11 (18) Index admission: 12 (46) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Büchler et al. | 79 (79) | NR | 52 (65.8) | SCT < lower reference rangec; urine or serum fluorescein-dilaurate test < lower reference range (NR) | 42 (53) | NR | NR | 19 (24) | 34 (43) | NR |

| Garnacho Montero et al. | 19 (19) | NR | NR | NBT-PABA test with urinary PABA recovery < 45% | 8 (42); Index admission: 19 (100) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Airey et al. | 59 (41) | NR | 0 (0) | NBT-PABA test with urinary PABA recovery < 55% | 29 (71); Index admission: 26 (63) | 20 (49)f | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Glasbrenner et al. | 29 (29) | NR | 0 (0) | Fluorescein dilaurate test with peak serum fluorescein < 4.5 µg/ml; fecal chymotrypsin < 3 U/g | Index admission: 23 (79) | 0 (0) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Bozkurt et al. | 89 (53) | NR | 42 (47)d | Lundh meal test < lower reference ranged | 45 (85) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Seidensticker et al. | 38 (38) | NR | 1 (3) | SCT < lower reference rangec | 5 (13) | NR | 0 (0) | NR | 7 (18) | NR |

| Malecka-Panas et al. (a) | 47 (47) | NR | 0 (0) | SCT < lower reference rangec | 30 (64) | 6 (13) | NR | 14 (30) | 30 (64) | NR |

| Malecka-Panas et al. (b) | 30 (30) | NR | NR | SCT < lower reference rangec | 19 (63) | NR | NR | NR | 4 (13) | NR |

| John et al. | 50 (36) | NR | NR | Fecal chymotrypsin level < 3 U/g | 11 (31) | NR | NR | NR | 9 (18) | NR |

| Tsiotos et al. | 72 (44) | NR | 44 (100) | FFE > 7 g/d with or without fecal weight > 20% | 11 (25) | 11 (25) | 2 (5) | 16 (36) | NR | ECOG score |

| Appelros et al. | 79 (26) | 1 (1) | 31 (39) | Pathologic triolein breath test (1 point) with weight loss > 10% (1 point), low level of serum amylase (1 point), low fat diet to avoid diarrhea (1 point); ≥ 2 | 18 (69) | NR | 12 (34) | 19 (73) | NR | Working capacity |

| Ibars et al. | 63 (61) | NR | 0 (0) | FFE > 7 g/d; SCT < lower reference rangec; urinary pancreolauryl test < 25%; fecal chymotrypsin < 3 U/g | 2 (3) | NR | NR | 13 (21) | NR | NR |

| Boreham et al. | 23 (23) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | FE-1 < 200 µg/gg | 6 (26); Index admission: 8 (35) | NR | NR | 4 (17) | NR | NR |

| Napolitano et al. | 35 (35) | NR | 0 (0) | FE-1 < 200 µg/g | 4 (11) | NR | NR | 2 (6) | NR | NR |

| Sabater et al. | 39 (27) | NR | 12 (44) | FFE > 7 g/d for 3 days; fecal chymotrypsin < 6 U/g; SCT < lower reference rangec | 9 (33) | NR | NR | 13 (48) | NR | NR |

| Migliori et al. | 75 (75) | NR | 0 (0) | SCT with bicarbonate < 15 mmol, lipase < 150 U × 103; chymotrypsin < 160 U × 102; AACT < 14% | 41 (55) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Bavare et al. | 18 (18) | NR | 18 (100) | FFE > 7 g/d with or without steatorrhea and use of PERT | 9 (50); index admission: 13 (72) | 2 (11) | 3 (17) | 13 (72) | 16 (89) | Back to work |

| Symersky et al. | 34 (34) | NR | 6 (18) | FFE > 7 g/d for 2 days; NBT-PABA test with urinary PABA < 50% | 22 (65) | 10 (29) | 0 (0) | 12 (35) | NR | GIQLI |

| Reszetow et al. | 28 (28) | 0 (0) | 28 (100) | FE-1 < 200 µg/gg | 4 (14) | NR | NR | 22 (79) | 12 (42) | Core FACIT scale |

| Reddy et al. | 10 (10) | 0 (0) | 10 (100) | FFE > 7 g/d | 8 (80) | NR | NR | 5 (50) | 7 (70) | Back to work |

| Pelli et al. | 54 (54) | 8 (15) | NR | FE-1 < 200 µg/g with or without plasma fat-soluble vitamin A < 1 µmol/l or vitamin E < 12 µmol/l | 5 (9); index admission 21 (39) | NR | 10 (19) | 17 (37) | 18 (51) | NR |

| Pezzilli et al. | 75 (75) | 0 (0) | 5 (7) | FE-1 < 200 µg/gg | Index admission: 9 (12) | 0 (0) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Gupta et al. | 30 (30) | 0 (0) | 25 (83) | FFE > 7 g/d; urinary d-xylose excretion < 20% | 12 (40) | 4 (13) | 12 (40) | 12 (40) | 13 (43) | NR |

| Uomo et al. | 65 (40) | 2 (5) | 19 (48) | Serum pancreoauryl test < 4.5 µg/ml; FE-1 < 200 µg/g | 9 (23) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (16) | 2 (5) | NR |

| Andersson et al. | 40 (40) | 1 (2.5) | 4 (10) | FE-1 < 200 µg/g | 1 (3) | 3 (8) | NR | 22 (55) | NR | SF-36 |

| Xu et al. | 65 (65) | 0 (0) | 5 (8) | FE-1 < 200 µg/gg | 38 (59) | 33 (51) | NR | NR | 20 (31) | NR |

| Garip et al. | 109 (109) | 13 (12) | 5 (5) | FE-1 < 200 µg/gg | 15 (14) | NR | NR | 33 (30) | NR | NR |

| Kahl et al. | 56 (56) | NR | NR | FE-1 < 200 µg/g | Index admission: 20 (36) | 26 (46)f | NR | NR | NR | FACT-Pa |

| Vujasinovic et al. | 100 (100) | NR | NR | FE-1 < 200 µg/gg with measuring serum iron, magnesium, folic acid and vitamins A, D, E and B12 | 21 (21) | NR | 25 (25) | 14 (14) | NR | NR |

| Winter Gasparoto et al. | 16 (16) | 0 (0) | 5 (31) | FFE with positive Sudan stain | 1 (6) | 1 (6) | NR | 12 (75) | 2 (13) | SF-36 |

| Chandrasekaran et al. | 35 (35) | 0 (0) | 21 (60) | FFE > 7 g/d | 14 (40) | 21 (60) | 3 (8.6) | 17 (48.6) | NR | NR |

| Ermolov et al. | 210 (80) | NR | 136 (65)e | FE-1 < 200 µg/gg | 28 (35) | NR | 58 (28) | 62 (30) | 12 (15) | GIQLI |

| Nikkola et al. | 77 (45) | 5 (7)e | 0 (0) | FE-1 < 200 µg/g | 11 (24) | NR | 27 (35)e | 20 (26)e | 9 (12)e | NR |

| Koziel et al. | 150 (150) | 17 (11) | 18 (12) | FE-1 < 200 µg/gg | 21 (14) | NR | 44 (29) | 18 (14) | 58 (39) | SF-36 |

| Tu et al. | 113 (113) | 0 (0) | 73 (65) | FE-1 < 200 µg/gg | 40 (35) | NR | NR | 67 (59) | NR | NR |

| van Brunschot et al. | 98 (83) | 18 (18) | 98 (100) | FE-1 < 200 µg/gg | 41 (49) | 29 (35) | NR | 19 (23) | NR | NR |

EPI exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, DM diabetic mellitus, RAP recurrent acute pancreatitis, NR not reported, NBT-PABA N-benzoyl-l-tyrosyl-P-aminobenzoic acid, SCT secretin-cerulein (or pancreozymin) test, FFE fecal fat excretion, FE-1 fecal elastase-1, AACT amino acid consumption test, PERT pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy, GIQLI Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index, FACIT Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy, SF-36 Short Form 36 Health Survey Questionnaire, FACT Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy

aIncluded necrosectomy, drainage and local lavage procedures

bData refer to follow-up studies if not otherwise stated and with maximal numbers of EPI during observational period

cBicarbonate < 70 mEq/l, lipase < 97 kUI/h, chymotrypsin > 11 kUI/h

dLundh test meal amylase < 11,000 U/h, lipase < 110,000 U/h and trypsin < 7000 U/h

eData are derived from original enrolled patients rather than actual analyzed patients

fContained all the patients in the PERT arm in a randomized controlled trial comparing placebo versus PERT

gThese studies defined severity of EPI with FE-1 levels: 100–200 µg/g mild to moderate and < 100 µg/g severe

In the 39 follow-up studies, body mass index, alcohol history, cigarette smoking and symptoms of EPI were rarely recorded (data not shown). Nine studies [24, 38, 48, 51, 52, 54, 60, 61, 64] had a minor proportion of pre-existing DM (1.3–18%), 8 [40, 46, 47, 50, 53, 57, 58, 62] had none, and the remaining 22 [25–37, 39, 41–45, 56, 59, 63] did not report; 22 [26, 28, 32, 33, 37, 38, 42, 44–47, 50–54, 57–59, 61, 62] had a proportion of patients who had undergone pancreatic interventions; 10 [25, 30, 31, 34, 39–41, 43, 60, 63] reported no pancreatic interventions, and the remaining 7 [24, 27, 29, 35, 36, 48, 56] did not report.

Results of the Meta-Analysis

There were insufficient data for quantitative meta-analysis of the effects of PERT versus placebo in the two RCTs [30, 55]. The results of meta-analysis are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Results of meta-analyses

| Variable | No. of studies | No. of patients | No. of EPI | Effect estimate | Heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pool prevalence, % (95% CI) | I2 (%) | P value | ||||

| Overall during index admission | 10 | 370 | 183 | 62 (39–82) | 95 | < 0.0001 |

| Index admission versus follow-upa | ||||||

| Index admission | 8 | 240 | 154 | 71 (50–89) | 92 | < 0.0001 |

| Follow-up | 8 | 210 | 69 | 33 (17–53) | 88 | < 0.0001 |

| Mild versus severe (OAC) | ||||||

| Mild | 3 | 101 | 34 | 46 (0–99) | 98 | < 0.0001 |

| Severe | 3 | 27 | 13 | 66 (11–99) | 90 | < 0.0001 |

| Biliary versus alcohol | ||||||

| Biliary etiology | 5 | 116 | 51 | 72 (26–99) | 96 | < 0.0001 |

| Alcohol etiology | 6 | 87 | 50 | 87 (71–97) | 26 | 0.248 |

| Overall at follow-up | 39 | 1795 | 618 | 35 (27–43) | 91 | < 0.0001 |

| Mild versus severe (OAC) | ||||||

| Mild | 13 | 467 | 100 | 21 (11–33) | 89 | < 0.0001 |

| Severe | 23 | 847 | 345 | 42 (33–52) | 86 | < 0.0001 |

| Mild versus moderate to severe (RAC) | ||||||

| Mild | 4 | 160 | 24 | 16 (10–23) | 23 | 0.275 |

| Moderate | 2 | 27 | 7 | 27 (13–45) | 0 | 0.453 |

| Severe | 3 | 208 | 58 | 30 (15–47) | 82 | 0.004 |

| Biliary versus alcohol | ||||||

| Biliary etiology | 15 | 335 | 72 | 22 (12–33) | 81 | < 0.0001 |

| Alcohol etiology | 14 | 388 | 155 | 44 (27–60) | 91 | < 0.0001 |

| Other etiologies | 3 | 72 | 13 | 19 (11–29) | 0 | 0.726 |

| Female versus male | ||||||

| Female | 3 | 45 | 6 | 23 (1–64) | 79 | 0.01 |

| Male | 5 | 119 | 45 | 48 (26–71) | 82 | 0.0003 |

| Edematous versus necrotizing versus IPN | ||||||

| Edematous | 8 | 261 | 54 | 24 (14–36) | 77 | < 0.0001 |

| Necrotizing | 15 | 538 | 244 | 47 (36–58) | 84 | < 0.0001 |

| IPN | 11 | 398 | 188 | 48 (35–62) | 86 | < 0.0001 |

| Necrosis < 50% versus necrosis ≥ 50% | ||||||

| < 50% | 6 | 121 | 49 | 41 (17–68) | 86 | < 0.0001 |

| ≥ 50% | 6 | 81 | 45 | 58 (34–79) | 76 | 0.001 |

| Head versus body and/or tail | ||||||

| Head | 3 | 20 | 8 | 41 (22–62) | 0 | 0.661 |

| Body/tail | 3 | 79 | 27 | 34 (11–61) | 70 | 0.036 |

| Conservative versus necrosectomy | ||||||

| Conservative | 4 | 74 | 16 | 23 (12–35) | 24 | 0.267 |

| Necrosectomy | 9 | 183 | 73 | 48 (32–63) | 77 | < 0.0001 |

| Recurrent AP | 13 | 937 | 188 | 24 (17–31) | 82 | < 0.0001 |

| Prediabetic and/or DM versus EPIb | ||||||

| Prediabetes and/or DM | 27 | 1454 | 494 | 38 (31–45) | 87 | < 0.0001 |

| EPI | 27 | 1357 | 409 | 32 (24–40) | 90 | < 0.0001 |

| Pancreatic morphologic changes | 18 | 810 | 272 | 36 (27–45) | 87 | < 0.0001 |

EPI exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, CI confidence interval, OAC original Atlanta classification, RAC revised Atlanta classification, IPN infected pancreatic necrosis, AP acute pancreatitis, DM diabetic mellitus

aIncluded studies that simultaneously reported prevalence of EPI during index admission and at follow-up

bIncluded studies that simultaneously reported prevalence of EPI and prediabetic and/or DM

Prevalence of EPI During Admission and Follow-Up

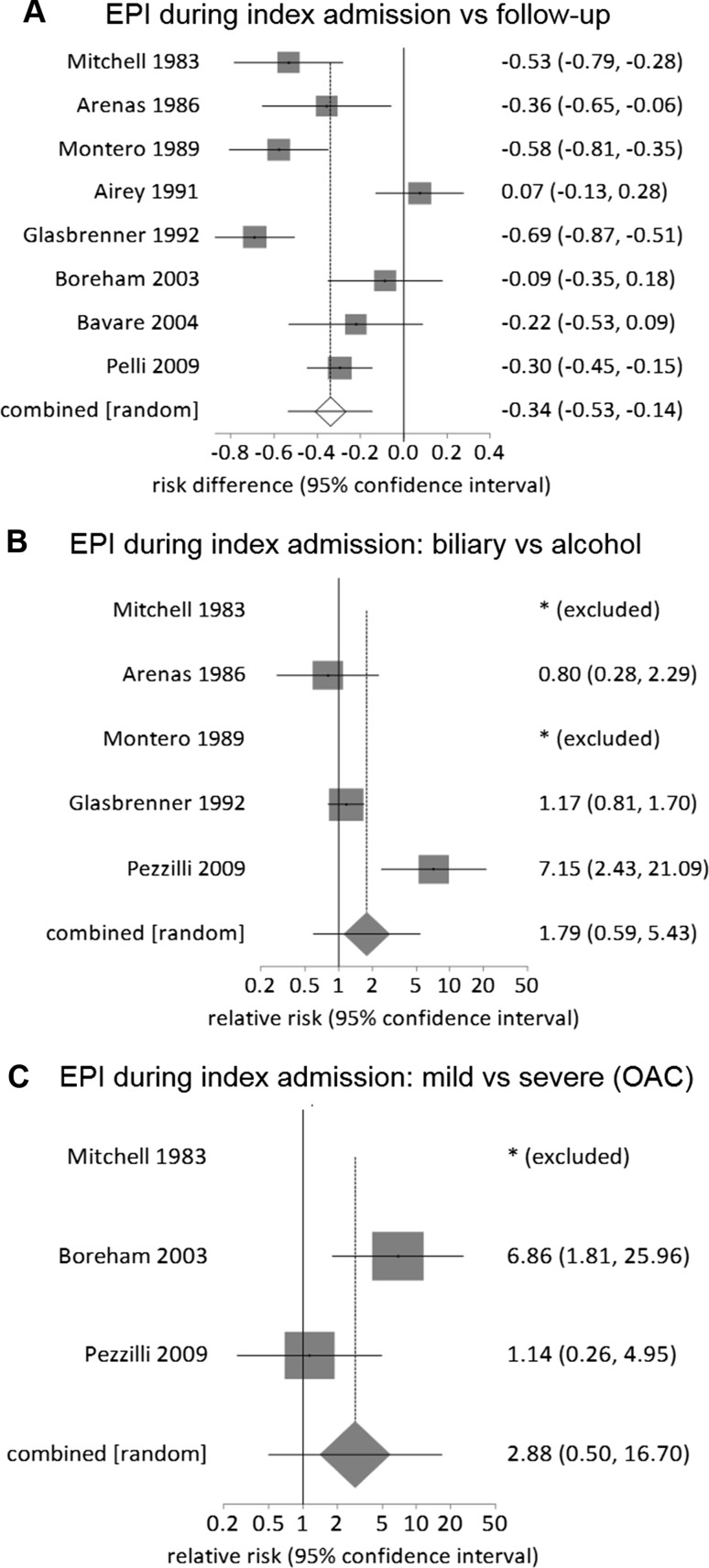

In the 10 index admission studies, 389 patients were enrolled and 370 analyzed (Supplementary Figure 1A). The pooled prevalence of EPI was 62% (95% CI 39–82%), with high statistical heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 95%). Of the eight studies [25, 27, 29–31, 40, 44, 48] that also provided data on EPI during follow-up, the pooled prevalence of EPI was 71% (50–89%) during the index admission and 33% (17–53%) during follow-up, respectively (Supplementary Figure 1B and 1C), showing that the prevalence of EPI halved (RD: − 0.34, − 0.53 to − 0.14) during follow-up (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Relative risk comparison for prevalence of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency during index admission of acute pancreatitis: a index admission versus follow-up, b biliary versus alcohol (original Atlanta classification, OAC) and c mild versus severe (OAC)

Five studies [25, 27, 29, 31, 49] of EPI during the index admission compared alcohol versus gallstone etiology (RR: 1.79, 0.59–5.43, P = 0.35; Fig. 2b), and three [25, 40, 49] compared OAC severe versus mild AP (RR: 2.9, 0.5–16.7, P = 0.24; Fig. 2c), both showing no significant difference. No data were quantitively synthesized for gender and necrosis.

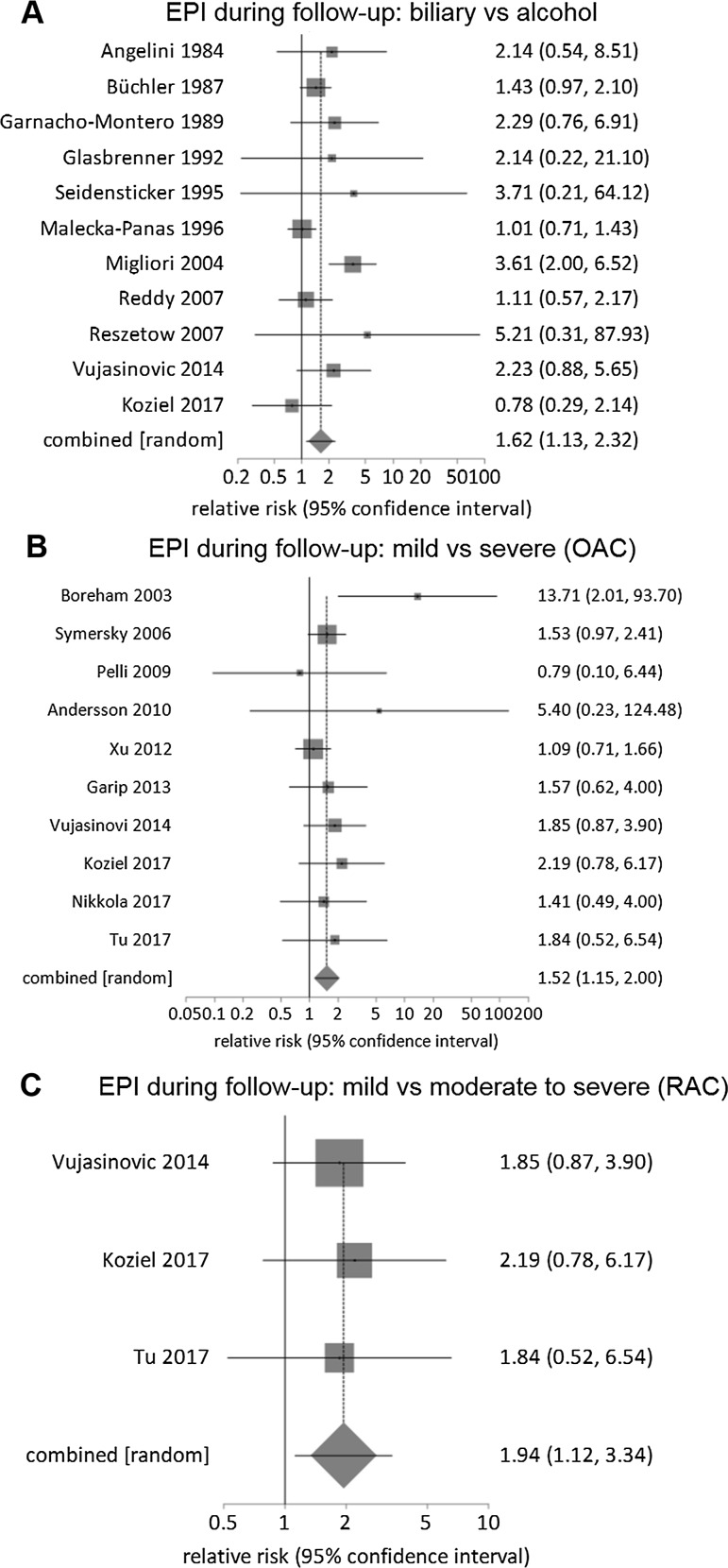

Prevalence of EPI During Follow-Up Alone

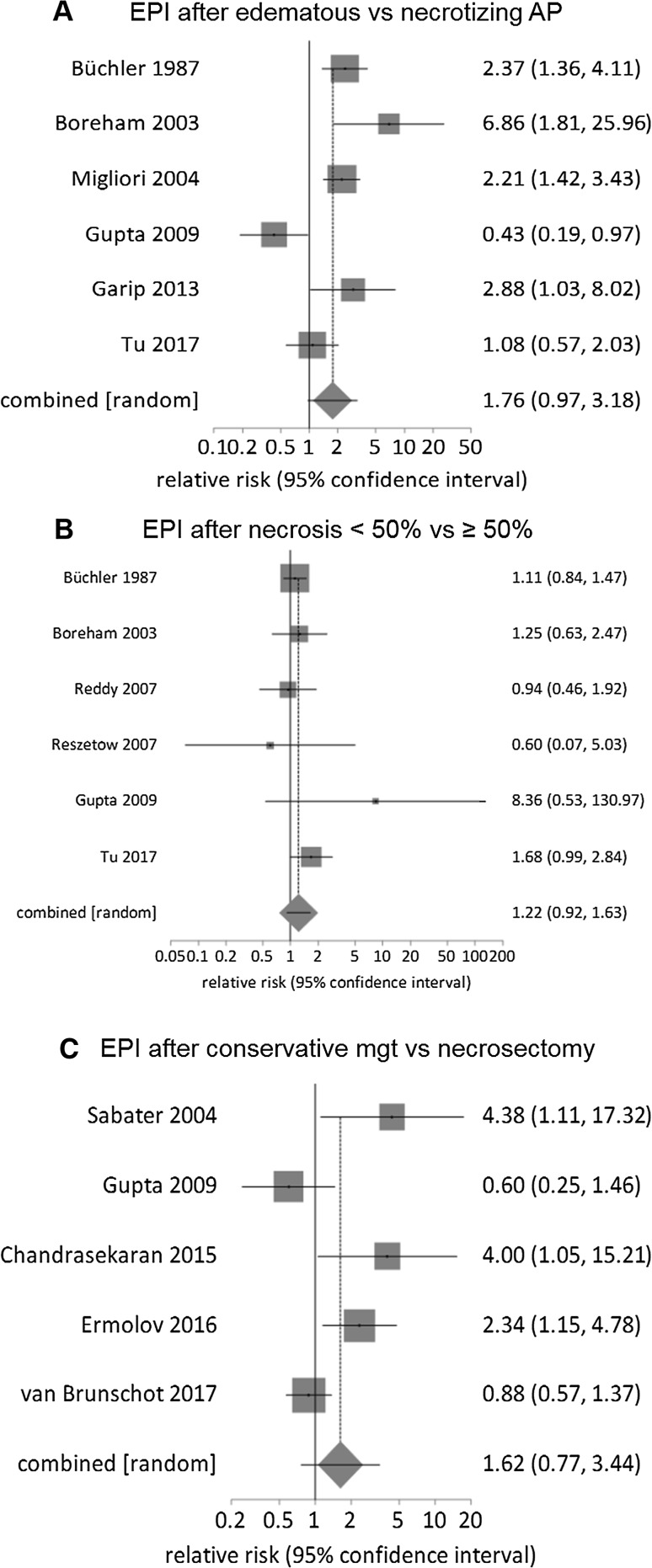

In the 39 follow-up studies, 2168 patients were enrolled and 1795 analyzed (Table 4 and Supplementary Figure 2). The pooled prevalence of EPI was 35% (27–43%), with high statistical heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 92%). The pooled prevalence of EPI was 21% for OAC mild AP (13 studies) (Supplementary Figure 3A), 42% for OAC severe AP (23 studies) (Supplementary Figure 3B), 16% for RAC mild AP (4 studies) (Supplementary Figure 4A), 27% for RAC moderately severe AP (2 studies) (Supplementary Figure 4B) and 30% for RAC severe AP (3 studies) (Supplementary Figure 4C). The pooled prevalence of EPI was 24% for edematous AP (8 studies) (Supplementary Figure 5A), 47% for necrotizing AP (15 studies) (Supplementary Figure 5B) and 48% for IPN (11 studies) (Supplementary Figure 5C).

There was no significant difference in the prevalence of EPI during follow-up for gender (RR: 1.5, 0.4–6.3, P > 0.5; 3 studies) [46, 47, 56] (Table 4). There was a significantly higher prevalence of EPI for patients with alcohol etiology compared with gallstones (RR: 1.6, 1.1–2.3, P = 0.01; 11 studies) [26, 28, 29, 31, 33–35, 43, 46, 47, 56, 61] (Fig. 3a). There was a higher prevalence of EPI in patients with OAC severe AP versus mild AP (RR: 1.5, 1.2–2, P = 0.003, 10 studies) [40, 45, 48, 52–54, 56, 60–62] (Fig. 3b); in RAC moderately severe/severe versus mild AP (RR: 2, 1.1–3.4, P = 0.018, 3 studies) [56, 61, 62] (Fig. 3c); in necrotizing versus edematous AP (RR: 1.8, 1–3.2, P = 0.06; 6 studies) [28, 40, 43, 50, 54, 62] (Fig. 4a). There was no significant difference in the prevalence of EPI for ≥ 50% necrosis versus < 50% necrosis (RR: 1.2, 1–1.6, P = 0.172, 6 studies) [28, 40, 46, 47, 50, 62] (Fig. 4b), for pancreatic head versus body and/or tail necrosis (RR: 1.1, 0.6–2, P > 0.5; 3 studies) [46, 47, 62] (Table 4) or for patients having necrosectomy versus conservative management (RR: 1.62, 0.8–3.44, P = 0.205; 5 studies) [42, 50, 58, 59, 64] (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 3.

Relative risk comparison for prevalence of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency for all follow-up studies of acute pancreatitis: a biliary versus alcohol (original Atlanta classification, OAC), b mild versus severe (OAC) and c mild versus moderate to severe (revised Atlanta classification, RAC)

Fig. 4.

Relative risk comparison for prevalence of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency at follow-up focused on acute necrotizing pancreatitis: a edematous versus necrotizing; b necrosis < 50% versus ≥ 50%; c conservative management (mgt) versus necrosectomy

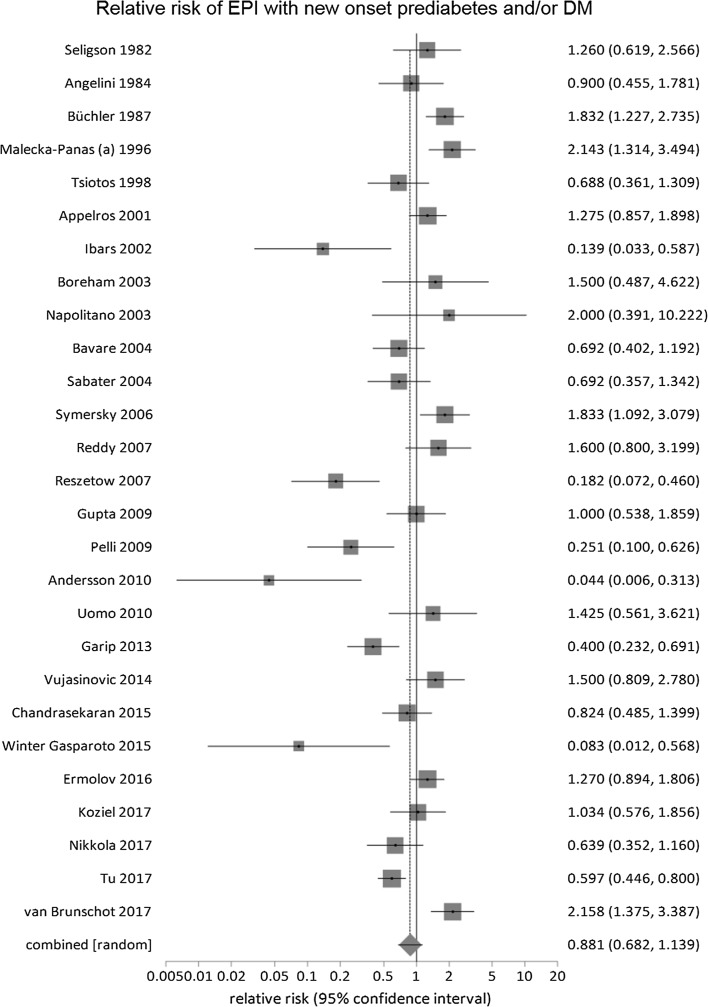

The pooled prevalence for recurrent AP, pre-diabetes and/or DM and pancreatic morphologic changes was 24% (17–31%), 38% (31–45%) and 36% (27–45%), respectively (Table 4). In the studies [24, 26, 28, 34, 37–42, 44–48, 50–52, 54, 56–62] that reported on the occurrence of EPI and new-onset pre-diabetes and/or DM, the pooled prevalence of EPI was 32% (24–40%), without any statistically significant difference between the two (RR of EPI in patients developing new-onset pre-diabetes and/or DM: 0.8, 0.7–1.1, P = 0.33) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Relative risk comparison for prevalence of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) versus pre-diabetes and/or diabetes mellitus (DM) for all follow-up studies of acute pancreatitis that reported these two parameters simultaneously

In eight studies [40, 46, 53, 54, 56, 59, 61, 62] that reported the severity of EPI and used the FE-1 test, the pooled prevalence of mild to moderately severe EPI was 16% (CI 10–24%) (Supplementary Figure 6A) and of severe EPI was 11% (CI 6–17% (Supplementary Figure 6B).

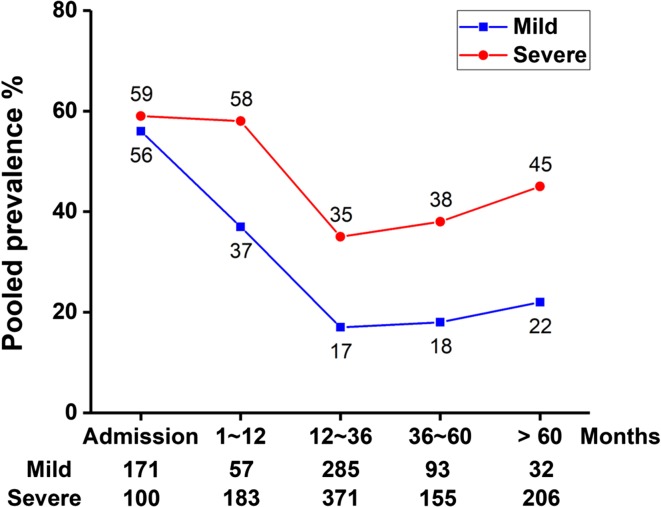

The prevalence of EPI for long-term follow-up is shown in Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 2. These data demonstrate that there was a steady decrease in the prevalence of EPI after AP from the index admission over the subsequent 5 years of follow-up (OAC severe AP 59–38%, OAC mild AP 56–18%), but beyond 5 years there was a modest rise in prevalence.

Fig. 6.

Time course of the pooled prevalence of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency during and for > 5 years after an attack of acute pancreatitis obtained from all included studies

Subgroup Analyses

Subgroup analyses found that study quality, sample size and Western population did not affect the primary meta-analysis results (Supplementary Table 2). Gallstone etiology had a decreased prevalence of EPI compared with the primary analysis, whereas alcohol etiology had an increased prevalence of EPI. None of these factors significantly affected the statistical heterogeneity.

Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses found that in the studies that used the FE-1 test there was a lower pooled prevalence of EPI (Supplementary Table 3). In contrast, the sensitivity analyses found that the primary meta-analysis results were not affected by restriction to first episodes of AP, the proportion of patients with pre-existing DM, the proportion of patients who had undergone pancreatic intervention or the use of direct, indirect or FFE tests to diagnose EPI. None of these factors significantly affected statistical heterogeneity.

Meta-regression Analysis

Meta-regression analyses did not identify any significant contributing factor to study heterogeneity by any pre-defined criterion except the year of publication for the follow-up study (Supplementary Table 4).

Publication Bias

Funnel plots for publication bias are shown in Supplementary Figure 6. There was no publication bias identified for admission studies (n = 10), follow-up studies (n = 39) or OAC severe AP patients (Begg-Mazumdar and Egger tests P > 0.1). There was significant publication bias for the follow-up studies of OAC mild AP patients (both Begg-Mazumdar and Egger tests P < 0.05).

Discussion

By combining data from a total of 41 studies, we found EPI in over half (62%) of all AP patients during their index admission, including patients of all grades of severity. One third (35%) of all AP patients were found to have EPI during follow-up, significantly more after severe AP compared with mild AP or necrotizing AP compared with edematous AP. Note that EPI was not restricted to patients who had extensive pancreatic necrosis, as almost half (46%) of patients who had mild AP were found to have EPI during their index admission and one fifth during follow-up. Patients who had pancreatic necrosis ≥ 50%, underwent necrosectomy and head necrosectomy had increased, but not statistically significantly, RR of EPI compared with those who had necrosis < 50%, conservative procedures and body/tail necrosectomy, respectively. The prevalence of EPI and new-onset pre-diabetes/diabetes was similar in studies reporting both complications.

There was a progressive decrease in the prevalence of EPI during the follow-up period, to about half at 5 years. Beyond 5 years, prevalence rose modestly, which may have resulted from a focus on more severe and/or progressive disease evidenced by biased reports for mild AP from our publication bias analysis. These data show that recovery from EPI after AP may take many months. AP can be associated with patchy necrosis of many different cell types in the pancreatic parenchyma, exacerbated in inflammation, with disruption of the normal microscopic architecture and complex, coordinated machinery of secretion [65]. The high prevalence of EPI in patients with AP during their index admission is consistent with such microscopic changes and their effects on exocrine function. There are many data indicating that the murine exocrine pancreas has the capacity to recover or regenerate after experimental AP, but no direct evidence of human exocrine pancreatic regeneration after AP has previously been provided [65]. There is thus a notable and consistent decrease in the prevalence of EPI over the first 12 months after index admission, which is likely to result from resolution of inflammation, repair, remodeling and regeneration. However, it is also noteworthy that at 5 years this recovery remains incomplete in over a third of affected patients, including 15–20% of all those who had mild AP. In these patients EPI persists and can increase in the long term.

Estimates of the prevalence of EPI after AP made without formal exocrine function tests may be misleading. For example, a large population-based study [66] from Taiwan included 12,284 patients after a first episode of AP, of whom 94% had OAC mild AP and 46% were prescribed PERT for EPI during follow-up. A US multicenter retrospective study of 167 patients found 30 (28%) of 106 who had a first episode of necrotizing AP were subsequently prescribed PERT for EPI [67]. In contrast, an Italian multicenter retrospective questionnaire study of 631 patients found 10 (2%) of 558 who had OAC mild AP and 6 (8%) of 73 who had severe AP developed overt steatorrhea [68]. In a meta-analysis investigating the relationship between exocrine and endocrine failure after AP [14], summary data from a total of 8 studies including 234 patients identified new-onset pre-diabetes and/or DM in 91 (41% of 221 identified by standard criteria or requirement for therapy) and EPI (by either formal exocrine function testing or reported requirement for PERT) in 59 (27% of 220). This study did not explore the impact of gender, etiology or AP severity, EPI during the index admission, the progression of EPI over time, the role of PERT or the potential effects of EPI on quality of life. The recent meta-analysis by Hollemans et al. [6] used diagnostic laboratory testing for EPI and found a pooled prevalence of EPI was 27.1% of 1495 AP patients analyzed at 36 months (median).

An alcohol etiology had a twofold RR for EPI after AP compared with other etiologies. This is consistent with the repeated injury that occurs with prolonged and excessive consumption of alcohol [69] with the risk of atrophy and fibrosis. In these patients there is an increased risk of recurrent AP and/or chronic pancreatitis [12]. Smoking, more common among those who consume excess alcohol, is known to increase the risk of chronic pancreatitis [70–72]. Given that repair and the reduction in EPI occurs over many months, it is important to cease alcohol consumption and to maintain prolonged abstinence. This is supported by the low incidence of EPI (6%) during long-term follow-up of abstinent patients who had alcohol-associated AP [73].

Regarding testing (direct and indirect) for EPI, all the tests found similar prevalence rates for EPI except FE-1. This was used in more recent studies and identified a significantly lower prevalence of EPI. While the FE-1 test is easy to perform and cost-effective for RAC severe patients (sensitivity and specificity > 90%) [74], the sensitivity for RAC mild/moderately severe AP is low (~60%) and fails to identify many patients with EPI.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses did not alter our findings, despite the significant heterogeneity between studies. Tests used to diagnose EPI contributed to this heterogeneity, but it was not possible to determine the contribution of the definitions and methods of identification of etiology, application of severity classification, follow-up periods and time points of investigation. Nor did we contact authors for further data, as we considered it highly unlikely that this would alter our principal findings.

The prevalence and persistence of EPI after AP indicate that up to a third of patients are at risk of malnutrition and malabsorption for prolonged periods after AP, and they may well increase after 5 years. AP induces many catabolic responses, resolution of which EPI may delay; the longer EPI persists, the greater the potential impact of malabsorption and malnutrition; thus, early PERT requirement may be indicated. Hollemans et al. [6] and our findings confirm that EPI may develop after AP of any severity, justifying routine symptom enquiry and a simple test of exocrine pancreatic function during follow-up, e.g., the FE-1 test.

Apart from the limitations reported by Hollemans et al. [6] for such a meta-analysis, different methods used to measure EPI may create the high heterogeneity between studies. Also, healthy inequalities that may cause unexplained heterogeneity were rarely reported by the included studies. This study also highlighted the high prevalence of EPI during AP admission regardless of disease severity, and there was a lack of studies to investigate the effect of PERT on EPI during admission and at follow-up.

In conclusion, there is a significant and largely unrecognized prevalence of EPI after AP. Taking into account the data from this study and other published studies, a number of practical recommendations can be made:

EPI should be tested for in all patients with AP before discharge from index admission, irrespective of the predicted severity.

PERT may be considered for patients with persistent EPI (e.g., FE-1 < 100–200 µg/g) after AP has resolved. Patients who were likely to develop persistent EPI included those with moderately severe and severe AP, those with pancreatic necrosis, those who have had a necrosectomy and those with an alcohol etiology.

Re-testing for EPI (off treatment) should be done at 3 months after discharge in all patients, e.g., a normal FE-1 test result would mean that PERT can be discontinued. For those who remain on PERT, testing should be repeated at 6 and 12 months.

These recommendations will require prospective validation studies, but withholding PERT until further evidence is available is not justified. Further research is needed to refine diagnostic methods for EPI, to determine optimal PERT strategies and to address the impact of health inequalities.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Michael Chvanov, PhD, of the Department of Cellular and Molecular Physiology at the University of Liverpool for the translation of Russian into English to enable completion of this study. This study was partially supported by the Key Technology R&D Program of Sichuan Provincial Department of Science and Technology (grant no. 2015SZ0229; QX) and NZ-China Strategic Research Alliance 2016 Award (China: 2016YFE0101800, QX, WH and LD.; New Zealand: JAW); the Liverpool China Scholarships Council (XZ); the University Hospital of Santiago de Compostela funds, Spain (DdlIG, IB-R, CC-S, JL-N, JI-G and JED-M); the Biomedical Research Unit Funding Scheme of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR; WH and RS); the NIHR Senior Investigator Scheme (RS).

Authors' contributions

WH and DdlIG are co-first authors. WH, DdlIG, JED-M and RS conceived and designed the study. WH, DdlIG, IB-R, CC-S, JL-N, JI-G, NS, XZ, WC, LD and DM acquired, analyzed and interpreted the data. WH, DdlIG, JED-M and RS drafted the manuscript. VKS, QX, JAW, JED-M and RS undertook critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. WH and DdlIG performed the statistical analyses. WH, QX, JED-M and RS obtained the funding. All authors approved the final version of the article.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

JED-M has provided consultancy to and received financial support from Abbott (Mylan) for lecture fees and travel expenses outside of the submitted work; RS has provided consultancy to Abbott (Mylan); no further support from any organization for the submitted work; no the financial relationships with any organizations that might have had an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Footnotes

Wei Huang and Daniel de la Iglesia-García are co-first authors.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

J. Enrique Domínguez-Muñoz, Phone: +34 981951364, Email: enriquedominguezmunoz@hotmail.com.

Robert Sutton, Phone: +44 (0) 151 706 2403, Email: r.sutton@liverpool.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Yadav D, O’Connell M, Papachristou GI. Natural history following the first attack of acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1096–1103. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Das SL, Singh PP, Phillips AR, et al. Newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus after acute pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2014;63:818–831. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pendharkar SA, Salt K, Plank LD, et al. Quality of life after acute pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pancreas. 2014;43:1194–1200. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Machicado JD, Gougol A, Stello K, et al. Acute pancreatitis has a long-term deleterious effect on physical health related quality of life. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1435–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sankaran SJ, Xiao AY, Wu LM, et al. Frequency of progression from acute to chronic pancreatitis and risk factors: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1490–1500. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hollemans RA, Hallensleben NDL, Mager DJ, et al. Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency following acute pancreatitis: systematic review and study level meta-analysis. Pancreatology. 2018;18:253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2018.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chowdhury RS, Forsmark CE. Review article: pancreatic function testing. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:733–750. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keller J, Layer P, et al. Diagnosis of pancreatic exocrine insufficiency in chronic pancreatitis. Pancreapedia. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non-randomized studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 1 June 2018.

- 11.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de la Iglesia-Garcia D, Huang W, Szatmary P, et al. Efficacy of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy in chronic pancreatitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2017;66:1354–1355. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vipperla K, Papachristou GI, Easler J, et al. Risk of and factors associated with readmission after a sentinel attack of acute pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1911–1919. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das SL, Kennedy JI, Murphy R, et al. Relationship between the exocrine and endocrine pancreas after acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:17196–17205. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i45.17196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradley EL., 3rd A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis. Summary of the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis, Atlanta, Ga, September 11 through 13, 1992. Arch Surg. 1993;128:586–590. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420170122019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis–2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102–111. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo Q, Li A, Xia Q, et al. The role of organ failure and infection in necrotizing pancreatitis: a prospective study. Ann Surg. 2014;259:1201–1207. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raraty MG, Halloran CM, Dodd S, et al. Minimal access retroperitoneal pancreatic necrosectomy: improvement in morbidity and mortality with a less invasive approach. Ann Surg. 2010;251:787–793. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d96c53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Grinsven J, van Santvoort HC, Boermeester MA, et al. Timing of catheter drainage in infected necrotizing pancreatitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:306–312. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sterne JA, Egger M, Smith GD. Systematic reviews in health care: investigating and dealing with publication and other biases in meta-analysis. BMJ. 2001;323:101–105. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7304.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seligson U, Ihre T, Lundh G. Prognosis in acute haemorrhagic, necrotizing pancreatitis. Acta Chir Scand. 1982;148:423–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell CJ, Playforth MJ, Kelleher J, et al. Functional recovery of the exocrine pancreas after acute pancreatitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1983;18:5–8. doi: 10.3109/00365528309181549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angelini G, Pederzoli P, Caliari S, et al. Long-term outcome of acute necrohemorrhagic pancreatitis. A 4-year follow-up. Digestion. 1984;30:131–137. doi: 10.1159/000199097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arenas M, Perez-Mateo M, Graells ML, et al. Evaluation of exocrine pancreatic function by the PABA test in patients with acute pancreatitis. Rev Esp Enferm Apar Dig. 1986;70:43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Büchler M, Hauke A, Malfertheiner P. Follow-Up After Acute Pancreatitis: Morphology and Function. Berlin: Springer; 1987. p. 367. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garnacho JM, Aznar AM, Corrochano MDD, et al. Evolucion de la funcion exocrina del pancreas tras la pancreatitis aguda. Factores pronosticos. Rev Esp Enferm Apar Dig. 1989;76:19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Airey MC, McMahon MJ. The influence of granular pancreatin upon endocrine and exocrine pancreatic function during convalescence from acute pancreatitis. In: Lankisch PG, editor. Pancreatic Enzymes in Health and Disease. Berlin: Springer; 1991. pp. 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glasbrenner B, Büchler M, Uhl W, et al. Exocrine pancreatic function in the early recovery phase of acute oedematous pancreatitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1992;4:563–567. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bozkurt T, Maroske D, Adler G. Exocrine pancreatic function after recovery from necrotizing pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1995;42:55–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seidensticker F, Otto J, Lankisch PG. Recovery of the pancreas after acute pancreatitis is not necessarily complete. Int J Pancreatol. 1995;17:225–229. doi: 10.1007/BF02785818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malecka-Panas E, Juszynski A, Wilamski E. Acute alcoholic pancreatitis does not lead to complete recovery. Mater Med Pol. 1996;28:64–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malecka-Panas E, Juszynski A, Wilamski E. The natural course of acute gallstone pancreatitis. Mater Med Pol. 1996;28:8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.John KD, Segal I, Hassan H, et al. Acute pancreatitis in Sowetan Africans. A disease with high mortality and morbidity. Int J Pancreatol. 1997;21:149–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsiotos GG, Luque-de Leon E, Sarr MG. Long-term outcome of necrotizing pancreatitis treated by necrosectomy. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1650–1653. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Appelros S, Lindgren S, Borgstrom A. Short and long term outcome of severe acute pancreatitis. Eur J Surg. 2001;167:281–286. doi: 10.1080/110241501300091462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ibars EP, Sanchez de Rojas EA, Quereda LA, et al. Pancreatic function after acute biliary pancreatitis: Does it change? World J Surg. 2002;26:479–486. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0253-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boreham B, Ammori BJ. A prospective evaluation of pancreatic exocrine function in patients with acute pancreatitis: correlation with extent of necrosis and pancreatic endocrine insufficiency. Pancreatology. 2003;3:303–308. doi: 10.1159/000071768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Napolitano L, Di Donato E, Faricelli R, et al. Experience on the pancreatic function after an episode of acute biliary oedematous pancreatitis. Ann Ital Chir. 2003;74:695–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sabater L, Pareja E, Aparisi L, et al. Pancreatic function after severe acute biliary pancreatitis: the role of necrosectomy. Pancreas. 2004;28:65–68. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200401000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Migliori M, Pezzilli R, Tomassetti P, et al. Exocrine pancreatic function after alcoholic or biliary acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2004;28:359–363. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200405000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bavare C, Prabhu R, Supe A. Early morphological and functional changes in pancreas following necrosectomy for acute severe necrotizing pancreatitis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2004;23:203–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Symersky T, van Hoorn B, Masclee AA. The outcome of a long-term follow-up of pancreatic function after recovery from acute pancreatitis. JOP. 2006;7:447–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reszetow J, Hac S, Dobrowolski S, et al. Biliary versus alcohol-related infected pancreatic necrosis: similarities and differences in the follow-up. Pancreas. 2007;35:267–272. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31805b8319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reddy MS, Singh S, Singh R, et al. Morphological and functional outcome after pancreatic necrosectomy and lesser sac lavage for necrotizing pancreatitis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2007;26:217–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pelli H, Lappalainen-Lehto R, Piironen A, et al. Pancreatic damage after the first episode of acute alcoholic pancreatitis and its association with the later recurrence rate. Pancreatology. 2009;9:245–251. doi: 10.1159/000212089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pezzilli R, Simoni P, Casadei R, et al. Exocrine pancreatic function during the early recovery phase of acute pancreatitis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2009;8:316–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gupta R, Wig JD, Bhasin DK, et al. Severe acute pancreatitis: the life after. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1328–1336. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0901-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uomo G, Gallucci F, Madrid E, et al. Pancreatic functional impairment following acute necrotizing pancreatitis: long-term outcome of a non-surgically treated series. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:149–152. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Andersson B, Pendse ML, Andersson R. Pancreatic function, quality of life and costs at long-term follow-up after acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4944–4951. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i39.4944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu Y, Wu D, Zeng Y, et al. Pancreatic exocrine function and morphology following an episode of acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2012;41:922–927. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31823d7f2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garip G, Sarandol E, Kaya E. Effects of disease severity and necrosis on pancreatic dysfunction after acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:8065–8070. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i44.8065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kahl S, Schutte K, Glasbrenner B, et al. The effect of oral pancreatic enzyme supplementation on the course and outcome of acute pancreatitis: a randomized, double-blind parallel-group study. JOP. 2014;15:165–174. doi: 10.6092/1590-8577/797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vujasinovic M, Tepes B, Makuc J, et al. Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency, diabetes mellitus and serum nutritional markers after acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:18432–18438. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i48.18432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Winter Gasparoto RC, Racy Mde C, De Campos T. Long-term outcomes after acute necrotizing pancreatitis: What happens to the pancreas and to the patient? JOP. 2015;16:159–166. doi: 10.6092/1590-8577/2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chandrasekaran P, Gupta R, Shenvi S, et al. Prospective comparison of long term outcomes in patients with severe acute pancreatitis managed by operative and non operative measures. Pancreatology. 2015;15:478–484. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ermolov AS, Blagovestnov DA, Rogal ML, et al. Long-term results of severe acute pancreatitis management. Khirurgiia (Mosk) 2016;10:11–15. doi: 10.17116/hirurgia20161011-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nikkola J, Laukkarinen J, Lahtela J, et al. The long-term prospective follow-up of pancreatic function after the first episode of acute alcoholic pancreatitis: recurrence predisposes one to pancreatic dysfunction and pancreatogenic diabetes. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:183–190. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Koziel D, Suliga E, Grabowska U, et al. Morphological and functional consequences and quality of life following severe acute pancreatitis. Ann Ital Chir. 2017;6:403–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tu J, Zhang J, Ke L, et al. Endocrine and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency after acute pancreatitis: long-term follow-up study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:114. doi: 10.1186/s12876-017-0663-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Braganza J, Critchley M, Howat HT, et al. An evaluation of 75 Se selenomethionine scanning as a test of pancreatic function compared with the secretin-pancreozymin test. Gut. 1973;14:383–389. doi: 10.1136/gut.14.5.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van Brunschot S, van Grinsven J, van Santvoort HC, et al. Endoscopic or surgical step-up approach for infected necrotising pancreatitis: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2018;391:51–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Murtaugh LC, Keefe MD. Regeneration and repair of the exocrine pancreas. Annu Rev Physiol. 2015;77:229–249. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021014-071727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ho TW, Wu JM, Kuo TC, et al. Change of both endocrine and exocrine insufficiencies after acute pancreatitis in non-diabetic patients: a nationwide population-based study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1123. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Umapathy C, Raina A, Saligram S, et al. Natural History after acute necrotizing pancreatitis: a large US tertiary care experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:1844–1853. doi: 10.1007/s11605-016-3264-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Castoldi L, De Rai P, Zerbi A, et al. Long term outcome of acute pancreatitis in Italy: results of a multicentre study. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:827–832. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li J, Zhou C, Wang R, et al. Irreversible exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in alcoholic rats without chronic pancreatitis after alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1843–1848. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB, Mullhaupt B, et al. Cigarette smoking accelerates progression of alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 2005;54:510–514. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.039263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yadav D, Whitcomb DC. The role of alcohol and smoking in pancreatitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:131–145. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cote GA, Yadav D, Slivka A, et al. Alcohol and smoking as risk factors in an epidemiology study of patients with chronic pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nikkola J, Raty S, Laukkarinen J, et al. Abstinence after first acute alcohol-associated pancreatitis protects against recurrent pancreatitis and minimizes the risk of pancreatic dysfunction. Alcohol Alcohol. 2013;48:483–486. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agt019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dominguez-Munoz JE, Hardt PD, Lerch MM, et al. Potential for screening for pancreatic exocrine insufficiency using the fecal elastase-1 test. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:1119–1130. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4524-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.