Abstract

This study uses National Inpatient Sample data to characterize trends in transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) in age groups 55 years and older in the United States from 2012 to 2015.

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) involves percutaneous implantation of bioprosthetic valves in patients with severe aortic stenosis. This technology received initial US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2011 for use in patients considered inoperable and, subsequently, in high-risk and intermediate-risk patients. These approvals, and subsequent clinical practice guidelines,1 were based on randomized clinical trials2,3 that enrolled mostly patients older than 65 years; more than 80% were older than 75 years. Because its use has expanded to patients with intermediate surgical risk, TAVR may be performed more frequently in patients younger than 65 years. Given uncertainty about the long-term durability of TAVR valves, we investigated how frequently TAVR is used in different age groups in the United States.

Methods

We used the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) from 2012 through 2015 (the most recent year available) and included all hospitalizations during which adult patients underwent TAVR and surgical AVR (SAVR). The NIS is a 20% stratified sample of all inpatient discharges from US nonfederal hospitals.4 Procedures were identified using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) and ICD-10-CM codes. Patient age was categorized into 4 groups: 55 years and younger, 56 to 65 years, 66 to 75 years, and 76 years and older. For each age group, we evaluated the trends in the use of TAVR and the proportion of TAVR among all AVRs using Cochran-Armitage trend tests. We analyzed TAVR by sex for each age group and compared using a χ2 test. All P values were 2-sided, with less than .05 denoting statistical significance. Analyses were performed using SAS (SAS Institute), version 9.4. This study was approved by the Weill Cornell Medicine institutional review board. Informed consent was waived due to the use of a deidentified national database.

Results

Among 72 417 AVRs, 13 772 (19.0%) were TAVR and 58 645 (81.0%) were SAVR (of which 38 704 [66.0%] used bioprosthetic valves and 19 941 [34.0%] used mechanical valves). For patients 55 years and younger, 207 (2.2%) received TAVR and 9074 (97.8%) received SAVR (3707 [40.9%] bioprosthetic); for patients aged 56-65 years, 602 (4.7%) received TAVR and 12 146 (95.3%) received SAVR (7334 [60.4%] bioprosthetic); for patients aged 66 to 75 years, 2088 (10.0%) received TAVR and 18 775 (90.0%) received SAVR (13 611 [72.5%] bioprosthetic); and for patients 76 years and older, 10 875 (36.8%) received TAVR and 18 650 (63.2%) received SAVR (14 052 [75.3%] bioprosthetic).

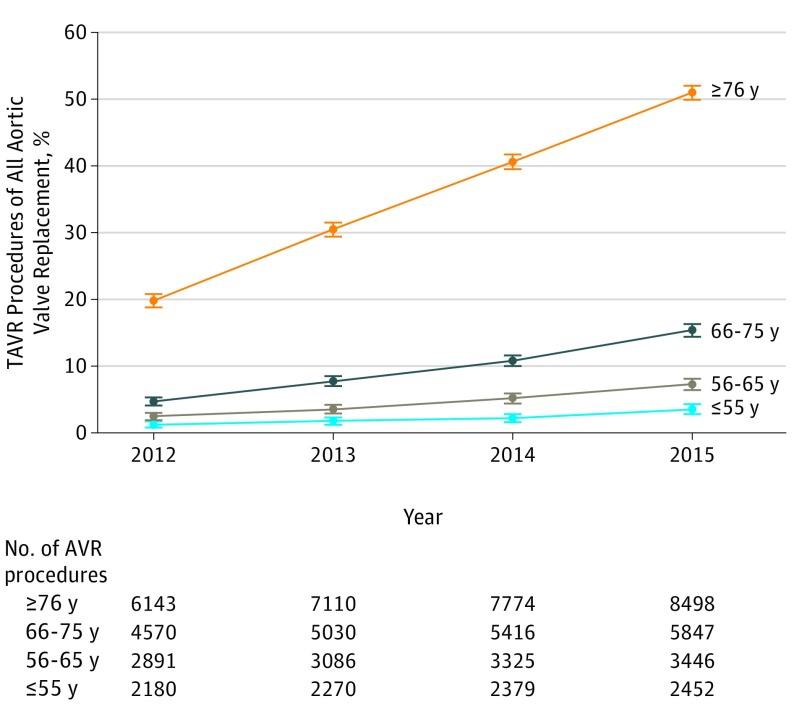

The number of TAVR procedures increased from 1531 in 2012 to 5567 in 2015 (Table). The use of TAVR as a proportion of all AVRs increased over time in all age groups (P < .001) (Figure). TAVR use increased among patients 55 years and younger and those aged 56 to 65 years (≤55 years: 1.2% [95% CI, 0.8%-1.7%] in 2012 to 3.5% [95% CI, 2.8%-4.3%] in 2015; 56 to 65 years: 2.5% [95% CI, 1.9%-3.0%] in 2012 to 7.3% [95% CI, 6.4%-8.1%] in 2015). Among TAVRs, the percentages of patients 55 years and younger and aged 56 to 65 years did not change significantly over time (≤55 years: 1.8% [95% CI, 1.1%-2.4%] in 2012 and 1.6% [95% CI, 1.2%-1.9%] in 2015; 56-65 years: 4.6% [95% CI, 3.6%-5.7%] in 2012 and 4.5% [95% CI, 3.9%-5.0%] in 2015) (Table). The proportion of women receiving TAVR was 30.9% (95% CI, 24.6%-37.2%) among patients 55 years and younger and 48.7% (95% CI, 47.8%-49.7%) among those 76 years and older (P < .001).

Table. Use of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR) by Age Group and Proportion of Women in Each Age Group, 2012-2015a.

| Age Groups, y | Year, No. of TAVRs (%) [95% CI] | P Valueb | Total TAVRs, No. (%) [95% CI] | Women Within Age Group, No. (%) [95% CI] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | ||||

| ≤55 | 27 (1.8) [1.1-2.4] |

40 (1.5) [1.0-1.9] |

53 (1.3) [1.0-1.7] |

87 (1.6) [1.2-1.9] |

.78 | 207 (1.5) [1.3-1.7] |

64 (30.9) [24.6-37.2] |

| 56-65 | 71 (4.6) [3.6-5.7] |

109 (4.0) [3.3-4.8] |

172 (4.3) [3.7-5.0] |

250 (4.5) [3.9-5.0] |

.75 | 602 (4.4) [4.0-4.7] |

260 (43.2) [39.2-47.1] |

| 66-75 | 215 (14.0) [12.3-15.8] |

389 (14.4) [13.1-15.7] |

586 (14.8) [13.7-15.9] |

898 (16.1) [15.2-17.1] |

.01 | 2088 (15.2) [14.6-15.8] |

929 (44.5) [42.4-46.6] |

| ≥76 | 1218 (79.6) [77.5-81.6] |

2167 (80.1) [78.6-81.6] |

3158 (79.6) [78.3-80.8] |

4332 (77.8) [76.7-78.9] |

.02 | 10 875 (79.0) [78.3-79.6] |

5299 (48.7) [47.8-49.7] |

| Total, No. | 1531 | 2705 | 3969 | 5567 | 13 772 | 6552 | |

Calculated from the survey sample of the National Inpatient Sample (unweighted). The 95% CIs need to be interpreted in the context of the NIS sample that is drawn from a finite population of US hospital discharges.

P value of the trend in proportions over all years.

Figure. Trends in the Proportion of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR) Among All AVRs by Year, 2012-2015 National Inpatient Sample.

Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Discussion

The number of patients overall and 65 years and younger in the NIS receiving TAVR increased annually from 2012 to 2015, as did the proportion of aortic valve replacements using TAVR. However, the distribution by age among TAVR procedures was unchanged. Data are lacking on the durability of the bioprosthetic valves implanted using TAVR, raising concern about use of TAVR and bioprosthetic valves in younger patients.5,6 Data from the NIS are only available through 2015 and current use of TAVR in 2018 has likely increased further. Younger patients may undergo TAVR due to higher risks for SAVR related to prior cardiac surgery; however, NIS does not have data on previous AVR or coronary artery bypass grafting. Patients 65 years and younger should be informed of the limited evidence for long-term outcomes with TAVR compared with SAVR in this age group. Registries and future trials should collect longer-term follow-up data for these patients.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(2):252-289. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack MJ, et al. ; PARTNER 2 Investigators . Transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(17):1609-1620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1514616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reardon MJ, Van Mieghem NM, Popma JJ, et al. ; SURTAVI Investigators . Surgical or transcatheter aortic-valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(14):1321-1331. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Overview of the National (nationwide) Inpatient Sample (NIS). https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. Accessed May 9, 2018.

- 5.Sedrakyan A, Dhruva SS, Shuhaiber J. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement in younger individuals. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):159-160. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glaser N, Jackson V, Holzmann MJ, Franco-Cereceda A, Sartipy U. Aortic valve replacement with mechanical vs biological prostheses in patients aged 50-69 years. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(34):2658-2667. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]