Abstract

Background

Concerns exist over the extrapolation of bioavailability studies of generic immunosuppressive drugs in healthy volunteers, regarding their efficacy and safety in kidney transplant recipients. We conducted a meta-analysis of trials examining the bioavailability of generic (test) immunosuppressive drugs relative to their brand (reference) counterparts in healthy volunteers, based on the US Food and Drug Administration requirements for approval of generics, and their efficacy and safety in kidney transplant recipients.

Methods

Eligible studies were identified in PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Scopus, ClinicalTrials.gov, and conference abstracts.

Results

Twenty crossover trials of healthy volunteers (n = 641) and 6 parallel-arm randomized controlled trials of kidney transplant recipients (n = 594) were identified. The 90% CI of the pooled test-to-reference drug ratio for maximum or peak plasma concentration (Cmax) and area under the plasma concentration time-curve from time 0 to time of last determinable concentration (AUC(0–t)) fell within the required range (0.80–1.25) for cyclosporine (Cmax 0.91; 90% CI 0.86–0.95; and AUC(0–t) 0.97; 90% CI 0.94–1.00), tacrolimus (Cmax 1.17; 90% CI 1.09–1.24; and AUC(0–t) 1.00; 90% CI 0.97–1.03) and mycophenolate mofetil (Cmax 0.98; 90% CI 0.96–1.01; and AUC(0–t) 1.00; 90% CI 0.99–1.01). In subgroup analyses, some generic cyclosporine formulations did not meet criteria for bioequivalence. No significant differences were observed in the time to maximum plasma concentration and terminal plasma half-life between generic and brand drugs. In parallel-arm trials, generic cyclosporine was non-inferior to brand counterpart in terms of acute allograft rejection, infections, and death.

Conclusions

Not all generic immunosuppressive drugs have similar relative bioavailability to their brand name counterparts. Evidence on their efficacy and safety is inconclusive. Tighter regulatory requirement for approval of generic drugs with narrow therapeutic index is needed.

Keywords: Drug, Immunosuppressant, Cyclosporine, Tacrolimus, Mycophenolate mofetil, Generic, Test, Brand, Reference, Bioequivalence, Efficacy, Safety, Kidney, Transplant

Introduction

Kidney transplantation for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) is associated with improved survival and quality of life, and health care cost reduction. In the United States, 30% of ESRD patients have a functioning kidney transplant [1], with annual per-patient cost for immunosuppressive medications estimated at $15,000–20,000 [2]. Under current Medicare policy, kidney transplant recipients lose coverage 36 months after transplantation, incurring the annual cost of immunosuppressive drugs thereafter. Considering that cost is an important determinant of medication nonadherence, it is not surprising that long-term kidney allograft survival rates in the United States are substantially lower compared to other developed countries, where lifetime access to immunosuppressive drugs is a right [2–4].

In an effort to reduce drug-related costs, generic substitutes have been introduced into the market [5]. Concerns, however, exist over the extrapolation of bioequivalence studies of generic immunosuppressive drugs in healthy volunteers, regarding their efficacy and safety in organ transplant recipients. For instance, there are reports of variability in the absorption of generic cyclosporine between healthy subjects and organ transplant recipients [6], and kidney transplant recipients receiving generic cyclosporine require higher doses or alternate immunosuppressive drugs [7]. Furthermore, the recall of an approved generic cyclosporine oral solution after a post-approval study had indicated non-bioequivalence to its brand counterpart, calls into question the generic drug approval process [8].

To summarize the available evidence, inform clinical practice, and provide future research directions, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of trials examining the bioavailability of generic immunosuppressive drugs, available worldwide, in healthy volunteers, based on the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requirements for approval of generics, focusing on cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF); we also reviewed the evidence on their efficacy and safety in kidney transplant recipients, relative to their brand counterparts.

Methods

The review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (online suppl. etable 1; for all online suppl. Material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000449020) [9].

Data Sources and Searches

The literature search and study selection were performed independently by 2 authors (N.R.G. and E.T.). The following electronic databases were searched for relevant citations (online suppl. etable 2): PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and ClinicalTrials.gov (inception to January 2015). Bibliographies of retrieved articles were inspected, and abstracts from scientific meetings of the American Transplant Society and American Society of Nephrology (up to 2014) were searched. The search strategy was limited to human studies with no restrictions on language, sample size, duration of study, or year of publication.

Study Selection

We followed the US FDA Guidance to Industry document on bioavailability and bioequivalence studies for orally administered drugs to identify relevant trials examining the relative bioavailability of generic to brand immunosuppressive drugs [10]. We searched for crossover trials independent of the number of study periods, and included trials of adults with a washout period of more than 5 half-lives, in accordance with the FDA guidance.

Regarding the efficacy and safety profile of generic relative-to-brand immunosuppressive drugs, we selected parallel-arm randomized controlled trials comparing the 2 formulations in kidney transplant recipients.

Data Extraction and Risk of Bias Assessment

Two authors (N.R.G. and E.T.) independently extracted data and assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane’s Collaboration tool [11]. The tool evaluates 6 domains of bias (selection, performance, detection, attrition, reporting, and other). Three additional domains deemed appropriate for crossover study design were added (suitability of crossover design, random order of treatment assignment, and presence of carry-over effect). Each domain’s risk of bias was assessed as low, high or unclear. Disagreements were resolved in consultation with a third author (B.L.J.). Authors of 4 trials were contacted for additional information.

The following data were extracted from crossover trials: country of origin, year of publication, health status, fasting state, study design, name of brand and generic immunosuppressant, drug formulation, washout and study period, drug dose, drug measurement assay, characteristics of study participants (gender, mean age, and weight), and outcomes of interest. From parallel-arm trials, the following additional data were extracted: kidney transplant type (deceased or living donor), time from transplantation, concomitant immunosuppressants, and study period.

The pharmacokinetic parameters of interest extracted from crossover trials included the mean area under the plasma concentration time-curve from time 0 to time of last determinable concentration (AUC(0–t)), maximum or peak plasma concentration (Cmax), time to maximum plasma concentration (Tmax), and terminal plasma half-life (T1/2) of the drug. For each parameter, the mean and SD of the test (generic) and reference (brand) drug was extracted. We also extracted or derived the arithmetic mean test-to-reference (T/R) drug ratio (i.e., generic-to-brand ratio) for the AUC(0–t) and Cmax, with the standard deviation and 90% CI [10]. For MMF, we extracted data on mycophenolic acid, the active metabolite that represents a better method of drug monitoring. Values reported as median with range were converted to mean with SD [12].

The safety and efficacy endpoints of interest extracted from parallel-arm trials included episodes of kidney allograft rejection, infections, adverse events (AEs), serious or severe AEs (SAEs), and death.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

The pharmacokinetic parameters were analyzed in accordance with the FDA guidance on bioavailability and bioequivalence studies of generic drugs [10]. For each immunosuppressant, randomeffects model meta-analyses were performed to compute the pooled weighted T/R drug ratio for the AUC(0–t) and Cmax with the 90% CI. Most trials reported arithmetic mean ratios with the corresponding 90% CI. When geometric mean values were reported, we calculated the arithmetic mean ratio (with the corresponding 90% CI) using a Taylor series approximation method [13]. When data for AUC(0–t) and Cmax were reported as geometric mean ratios, we used arithmetic mean data reported individually for the test and reference drug, and re-calculated the pooled arithmetic mean ratio with the 90% CI [13]. Pharmacokinetic parameters between the test and reference drug were deemed bioequivalent if the ratio of the mean values with the 90% CI fell within the 0.80–1.25 range, in accordance with FDA guidelines [10]. For Tmax and T1/2, random-effects model meta-analyses were performed to calculate the weighted mean difference (WMD) of the reference and test drug with the 95% CI.

Due to the low number of events, Peto fixed-effect model meta-analyses were used to calculate pooled ORs with 95% CI for the binary endpoints.

Existence of heterogeneity among study effect sizes was examined using the I2 index and the chi-square test p value. An I2 index ≥50% indicated moderate-to-high heterogeneity [14]. To investigate heterogeneity, we conducted subgroup analyses comparing the brand drug with each generic formulation. All analyses were performed using version 13 of the Stata® Data Analysis and Statistical Software (StataCorp LP, College Station, Tex., USA).

Results

Study Characteristics

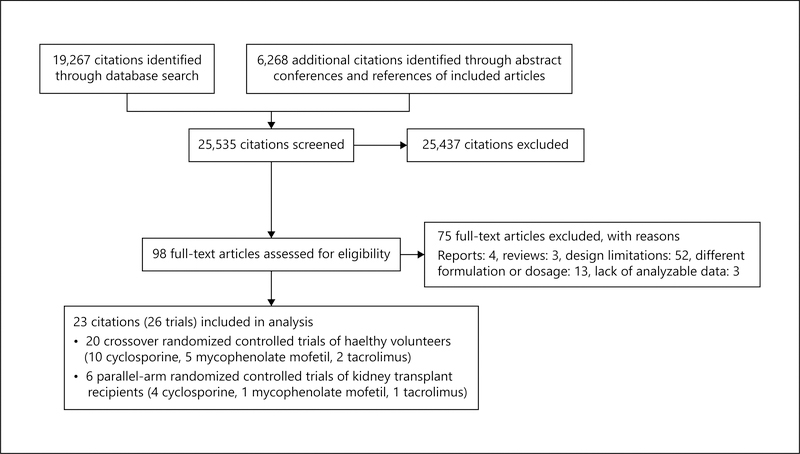

Potentially relevant citations, numbering 25,535 were identified and screened (fig. 1). Ninety-eight articles were retrieved for evaluation, of which 23 (26 trials) provided analyzable data [15–37]. Seventeen articles investigated relative bioavailability of generic to brand immunosuppressants, predominantly in healthy volunteers (table 1) [15–31]. No generic formulation identified in studies of healthy volunteers was approved for use in the United States. Six parallel-arm trials of kidney transplant recipients investigated the efficacy and safety of generic relative to brand immunosuppressants, of which only 2 (Equoral® and Gengraf®) were approved for use in the United States (table 2) [15, 32–36].

Fig. 1.

Study selection flow diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the bioequivalence crossover randomized controlled trials of healthy subjects included in the meta-analysis

| Author | Year | Country | Number of subjects | Age, years† | Men, % | Weight, kg | Generic immunosuppressant (manufacturer, country) | Oral formulation | Dose administered | Sampling interval, h | Washout period, days | Drug measurement assay | Lower limit of detection | Pharmacokinetic parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neoral® Sachdeva et al. [28] | 1997 | India | 12 | 17–35 | 100 | 50–79 | NR (Panacea Biotech Ltd., India) | Solution | 15 mg/kg | 24 | 7 | HPLC | NR | Cmax, AUC(0–24), AUC(0–∞), T1/2, Tmax |

| Tanasescu et al. [30] | 1999 | Romania | 24 | 21–40 | 50 | 52–90 | Sigmasporin Microoral (Sigma Pharma, Brazil) | NR | 2.5 mg/kg | 24 | 14 | HPLC | NR | Cmax, AUC(0–t), AUC(0–∞), T1/2, Tmax |

| Najib et al. [24] | 2003 | Jordan | 30 | 25 | NR | 71 | Sigmasporin Microoral (Gulf Pharmaceutical Industries, UAE) | Capsule | 100 mg | 24 | 7 | HPLC-MS | 5.0 ng/ml | Cmax, AUC(0–t), AUC(0–∞), T1/2, Tmax |

| Talaulikar et al. [29]* | 2003 | India | 30 | 34 | 83 | 50 | Arpimune ME (RPG Life Sciences Ltd., India) | Capsule | 4 mg/kg | – | 7 | RIA | NR | Cmax, AUC(0–t), Tmax |

| Mendes et al. [23] | 2004 | Brazil | 22 | 32 | 100 | 77 | Sigmasporin Microoral (Sigma Pharma, Brazil) | Capsule | 200 mg | 12 | 7 | FPAI | 21.8 mg/ml | Cmax, AUC(0–t), AUC(0–∞), T1/2, AUC(0–∞), T1/2, Tmax |

| Kees et al. [20] | 2004 | USA | 12 | 27 (22–32) | 100 | 74 | Cicloral (Hexal AG, Germany) | Capsule | 200 mg | 48 | 7 | HPLC | 15 ng/ml | Cmax, AUC(0–t), AUC(0–∞), T1/2 |

| Kees et al. [19]† | 2006 | Germany | 12 12 12 |

25 (22–29) 26 (23–30) 26 (24–30) |

100 | 72 78 74 |

Cicloral (Hexal AG, Germany) | Capsule Capsule Capsule |

100 mg 300 mg 600 mg |

48 48 48 |

7 7 7 |

HPLC | 15 ng/ml | Cmax, AUC(0–t), AUC(0–∞), T1/2 |

| Avramoff et al. [17] | 2007 | Israel | 24 | 19–40 | 100 | NR | Deximune (Dexel Pharma Ltd., Israel) | Capsule | 200 mg | 24 | 7 | FPAI | 50 mg/ml | Cmax, AUC(0–t), AUC(0–∞), T1/2, Tmax |

| Piñeyro-López et al. [37] | 2009 | Mexico | 34 | 22 (18–29) | NR | 78 | Zaven ME (RPG Life Sciences Ltd., India, imported by Gelpharma, S.A. de C.V., Mexico) | Capsule | 100 mg | 48 | 14 | HPLC-MS | 10 ng/ml | Cmax, AUC(0–t), AUC(0–∞), T1/2, Tmax |

| Wu et al. [31] | 2012 | China | 24 | NR | 100 | NR | NR (Sinopharm Chuankang Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., China) | Capsule | 400 mg | 48 | 7 | HPLC-UV | Cmax, AUC(0–t), AUC(0–∞), T1/2, Tmax | |

| Prograf® Park et al. [25]** | 2007 | South Korea | 29 | 29 | 76 | 66 | Tacrobell® (Chong Kun Dang, Seoul, Korea) | Capsule | 2 mg | 96 | 21 | LC/MS/MS | 0.5 ng/ml | Cmax, Cmin0–24, AUC(0–t), AUC(0–∞), AUC(0–24), C96 |

| Mathew et al. [22] | 2011 | India | 36 109 |

27 28 |

100 | 61 61 |

NR (Intas Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Gujarat, India) | Capsule Capsule |

0.5 mg 5 mg |

72 196 |

20 21 |

LC-MS/MS | 39.99 pg/ml 0.25 ng/ml |

Cmax, AUC(0–72),

AUC(0–∞),

T1/2 Cmax, AUC(0–t), AUC(0–∞), T1/2, Tmax |

| CellCept® Masri et al. [21] | 2007 | Czech Republic | 24 | 28 (6) | 83 | 77 | MMF 500 (Medis Laboratories, Tunisia) | Tablet | 500 mg | 24 | 8 | HPLC | NR | Cmax, AUC(0–t) |

| Almeida et al. [16]†† | 2010 | Spain, Québec | 100 | 38 | 62 | 68 | NR (Grupo Tecnimede, Tablet Portugal) | Tablet | 500 mg | 48 | 14 | LC-MS/MS | 19.95 ng/ml | Cmax, AUC(0–t), AUC(0–∞), T1/2 |

| Estevez-Carrizo et al. [18] | 2010 | Uruguay | 24 | 26 | 100 | 72 | Suprimum 500 (Laboratorios Clausen S.A., Uruguay) | Tablet | 500 mg | 36 | 7 weeks | HPLC | NR | Cmax, AUC(0–32), AUC(0–∞), Tmax |

| Patel et al. [26] | 2011 | India | 116 | 28 | 100 | 59 | NR (Intas Pharmaceuticals Ltd., India) | Tablet | 500 mg | 60 | 14 | LC-MS/MS | 75.43 ng/ml | Cmax, AUC(0–t), AUC(0–∞), T1/2 |

| Saavedra et al. [27] | 2011 | Chile | 22 | 28 | 100 | 75 | Linfonex (Laboratorios Recalcine S.A., Chile) | Tablet | 1,000 mg | 12 | 10 | HPLC | 0.3 μg/ml | Cmax, AUC(0–t), AUC(0–∞), T1/2 |

Multi-dose trial with participants on maintenance hemodialysis awaiting kidney transplantation

participants were administered 2 doses of each drug on the same day (morning and evening) and drug levels were measured 96 h after the first dose.

3-period crossover trial

4-period crossover trial; mean and/or range; all the trials were conducted in volunteers who were in a fasting state with the exception of one trial where the drug was administered with mango juice [28].

HPLC = High-performance liquid chromatography; MS = mass spectrometry; FPAI = fluorescence polarization immunoassay; RIA = radioimmunoassay; AUC0–∞ = area-under-the-curve to infinite time; NR = not reported; None of the generic immunosuppressants shown in the table are approved for use in the United States.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the parallel-arm randomized controlled trials included in the meta-analysis

| Author | Year | Country | Number of patients | Mean age, years | Men, % | Study period | Kidney transplant type (deceased/living donor) | Time since transplantation | Generic immunosuppressant (manufacturer, country) | Mean dose | Concomitant immunosuppressive regimen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neoral® Kim and Han [33] | 1998 | Korea | 40 | 39 | 75 | 4 weeks | 0/40 | 4 weeks | Neoplanta (Hanmi Pharma Co., Korea) | 10 mg/kg/day | NR |

| Khatami et al. [32] | 2013 | Iran | 221 | 39 | 61 | 1 year | 111/168 | NR | Iminoral (Arta Co., Iran) | 3–7mg/kg | Corticosteroids and mycophenolate mofetil |

| Vítko and Ferkl [35] | 2010 | Czech Republic, Poland, Romania | 99 | 42 | 70 | 6 months | NR | 3.9 years | Equoral® (IVAX Pharmaceuticals, Inc., USA)* | 2–6 mg/kg | Corticosteroids and mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine |

| Ong et al. [34] | 2007 | Malaysia | 106 | 41 | 54 | 6 months | 68/38 | 4.3 years | Gengraf® (Abbott Laboratories, USA)* | 150 mg | NR |

| CellCept® Abdallah et al. [15] | 2010 | Tunisia | 18 | 35 | 61 | 2 years | 4/14 | NR | MMF 500 (Medis Laboratories, Tunisia) | 2,000 mg | Prednisolone and tacrolimus |

| Prograf® Min et al. [36] | 2013 | Korea | 117 | 46 | 59 | 10 days | 63/54 | NR | Tacrobell® (Chong Kun Dang, Seoul, Korea) | NR | Prednisone, and mycophenolate mofetil |

NR = Not reported.

Approved by the FDA for use in the United States.

The relative bioavailability of generic cyclosporine was studied in 12 crossover trials and sub-studies [17, 19, 20, 23, 24, 28–31, 37]. Trials varied in sample size (12–34 subjects). With the exception of one trial of dialysis patients [29], the populations largely consisted of healthy adults. Neoral® was compared to generic Sigmasporin-Microoral®, Arpimune-ME, Zaven-ME, Deximune®, and Cicloral®. Two trials did not report the trade name of the generic drug [28, 31]. Most trials used a single-drug dose with 2 phases separated by 7 or 14 days, comprising >5 therapeutic half-lives.

In parallel-arm trials, Neoral® was compared to generic Neoplanta, Gengraf®, Equoral® or Iminoral [32–35]. Trials varied in sample size (13–221 patients) and duration of follow-up (1–24 months).

The relative bioavailability of generic MMF was studied in 5 single-dose cross-over trials [16, 18, 21, 26, 27]. CellCept® was compared to generic MMF500™, Linfonex™ or Suprimum 500®. Two trials did not report the trade name of the generic drug [16, 26]. The trials used a single-dose with 2 periods separated by a washout period ranging from 8 days to 7 weeks. One 2-year parallelarm trial of 18 kidney transplant recipients compared CellCept® to MMF500™ [15].

Two single-dose cross-over trials (one trial with 2 substudies) examined the relative bioavailability of generic tacrolimus in healthy volunteers [22, 25]. Prograf® was compared to Tacrobell® and an unspecified generic formulation. One parallel-arm trial of 117 kidney transplant recipients of 10-day duration compared Prograf® to Tacrobell® [36].

Risk of Bias Assessment

While all trials exhibited a lower risk of selection bias (random sequence generation and allocation concealment), there was a higher risk of performance bias (lack of blinding of participants and personnel), detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment), and reporting bias (selective reporting) (online suppl. efig. 1-3).

Pooled Analyses of Generic Cyclosporine Bioavailability Studies in Healthy Volunteers

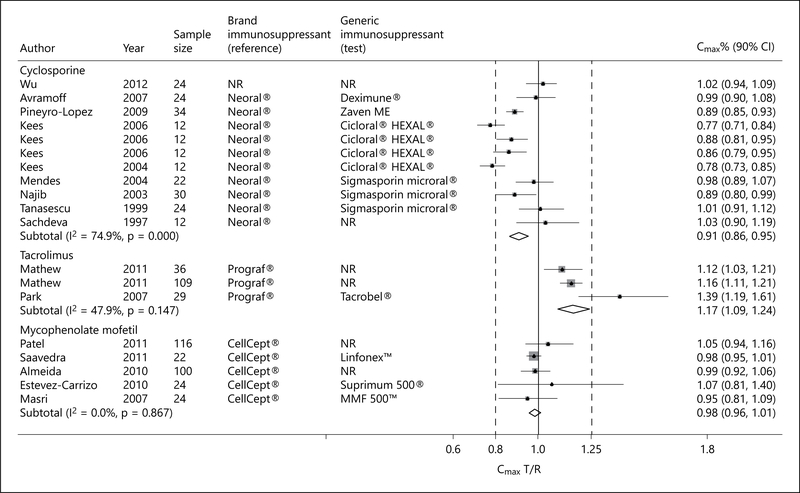

Eleven single-dose cross-over trials of healthy volunteers examined the relative bioavailability of generic cyclosporine formulations to Neoral® [17, 19, 20, 23, 24, 28, 30, 31, 37]. Although the pooled peak plasma concentration of generic cyclosporine formulations, as measured by the Cmax, was significantly lower than that achieved by Neoral®, the FDA requirement for bioequivalence was met (pooled Cmax T/R ratio 0.91; 90% CI 0.86–0.95; p = 0.001; fig. 2). However, there was significant heterogeneity (I2 = 74.9%; p < 0.001), 001; fig. 2). However, there was significant heterogeneity (I2 = 74.9%; p < 0.001), with inclusion of study participants of diverse geographic and ethnic background.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot displaying the pooled weighted ratio of the T/R immunosuppressive drug for the mean Cmax with the corresponding 90% CI. ‘Test’ refers to the generic immunosuppressive drug, and ‘reference’ to its brand counterpart.

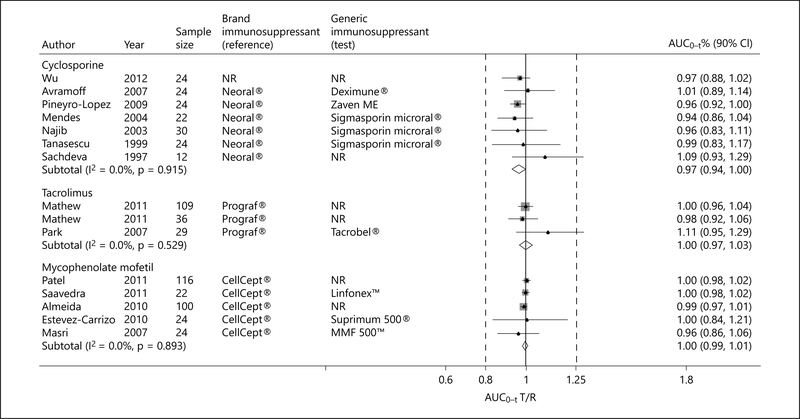

The pooled extent of absorption of generic cyclosporine, expressed as AUC(0–t), was also significantly lower than that achieved by Neoral®, but the FDA requirement for bioequivalence was also met (pooled AUC(0–t) T/R ratio 0.97; 90% CI 0.94–1.00; p = 0.001; fig. 3). There was no evidence of heterogeneity. Of note, however, in one study from India, the 90% CI of the AUC(0–t) T/R ratio exceeded the 0.8–1.25 range (AUC(0–t) T/R ratio 1.09; 90% CI 0.93–1.29), raising concerns about its potential safety in the studied population [28].

Fig. 3.

Forest plot displaying the pooled weighted ratio of the T/R immunosuppressive drug for the mean AUC(0–t)> with the corresponding 90% CI. ‘Test’ refers to the generic immunosuppressive drug, and ‘reference’ to its brand counterpart.

One trial adopted a different design testing multiple cyclosporine dosages and included dialysis patients awaiting kidney transplantation [29]. In a sensitivity analysis that included this study, the pooled Cmax and AUC(0–t) T/R ratio and respective 90% CI met the FDA requirement for bioequivalence (pooled Cmax T/R ratio 0.91; 90% CI 0.87–0.96; and pooled AUC(0–t) T/R ratio 0.97; 90% CI 0.94–0.99).

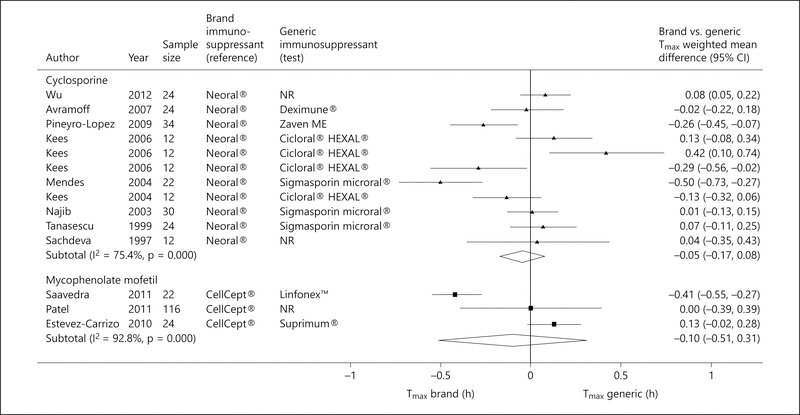

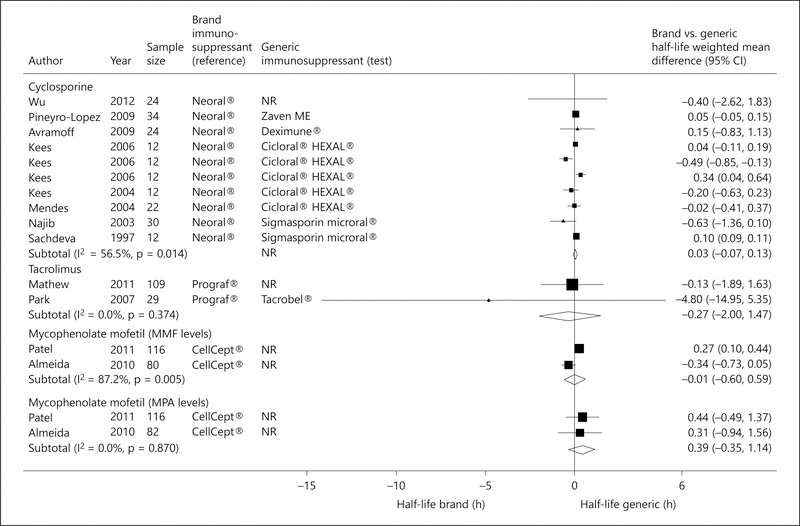

There was no significant difference between generic cyclosporine formulations and Neoral® with respect to Tmax (pooled WMD −0.05; 95% CI −0.17 to 0.08; fig. 4) [17, 19, 20, 23, 24, 28, 30, 31, 37] and T1/2 (pooled WMD 0.03; 95% CI −0.07 to 0.13; fig. 5) [17, 19, 20, 23, 24, 28, 31, 37].

Fig. 4.

Forest plot displaying the pooled weighted mean difference of the brand versus generic immunosuppressive drug for the mean Tmax, with the corresponding 95% CI. ‘Test’ refers to the generic immunosuppressive drug, and ‘reference’ to its brand counterpart.

Fig. 5.

Forest plot displaying the pooled weighted mean difference of the brand versus generic immunosuppressive drug for the mean T1/2, with the corresponding 95% CI. ‘Test’ refers to the generic immunosuppressive drug, and ‘reference’ to its brand counterpart.

Pooled Analyses of Generic Tacrolimus Bioavailability Studies in Healthy Volunteers

Three single-dose cross-over trials (2 citations) examined the relative bioavailability of generic tacrolimus formulations to Prograf® [22,25]. Although the pooled Cmax of generic tacrolimus formulations was significantly higher than that achieved by Prograf®, the FDA requirement for bioequivalence was met (pooled Cmax T/R ratio 1.17; 90% CI 1.09–1.24; p = 0.01; fig. 2). The pooled AUC(0–t) also met the FDA requirement for bioequivalence (pooled AUC(0–t) T/R ratio 1.00; 90% CI 0.97–1.03; p = 0.01; fig. 3). In one trial from Korea [25], the Cmax of Tacrobell® was greater than that achieved for Prograf®, raising concerns about the safety of this generic formulation. There was no significant difference between generic tacrolimus formulations and Prograf® with respect to T1/2 (pooled WMD −0.27; 95% CI −2.00 to 1.47; p = 0.76; fig. 5) [22, 25].

Pooled Analyses of MMF Bioequivalence Studies in Healthy Volunteers

Five trials examined the relative bioavailability of generic MMF formulations to CellCept® [16, 18, 21, 26, 27]. Although the pooled Cmax of MMF generic formulations was significantly lower than that achieved by CellCept®, the FDA requirement for bioequivalence was met (pooled Cmax T/R ratio 0.98; 90% CI 0.96–1.01; p = 0.001; fig. 2). The pooled AUC(0–t) also met the FDA requirement for bioequivalence (pooled AUC(0–t) T/R ratio 1.00; 90% CI 0.99–1.01; p = 0.001; fig. 3). No heterogeneity was detected. There was no significant difference between generic MMF formulations and CellCept® with respect to Tmax (pooled WMD −0.10; 95% CI −0.51 to 0.31; p = 0.98; fig. 4) [18, 26, 27] and T1/2 (pooled WMD 0.39; 95% CI −0.35 to 1.14; p = 0.30; fig. 5) [16, 26].

Pooled Analyses of Efficacy and Safety Studies in Kidney Transplant Recipients

Four parallel-arm trials, totaling 466 kidney transplant recipients, compared generic cyclosporine formulations to Neoral® [32–35]. All 4 trials reported on kidney allograft rejection [32–35], 2 trials on AEs and SAEs [34, 35], 3 trials on infections [32, 34, 35], and 3 trials on mortality [32, 34, 35]. Generic cyclosporine formulations appeared non-inferior to Neoral® with respect to acute allograft rejection (pooled OR 0.95; 95% CI 0.46–1.93), infections (pooled OR 0.91; 95% CI 0.52–1.60), AEs (pooled OR 1.01; 95% CI 0.55–1.85), SAEs (pooled OR 1.80; 95% CI 0.82–3.91), and death (pooled OR 2.77; 95% CI 0.39–19.75).

The evidence on efficacy and safety of MMF and tacrolimus was limited. One trial of 18 incident kidney transplant recipients observed a higher rate of acute kidney injury in patients receiving the reference drug CellCept® (66.6 vs. 14.3%); however, the 2 groups had comparable rates of acute allograft rejection (14.3 vs. 16.6%) [15]. In the single trial of 126 incident kidney transplant recipients examining the efficacy and safety of a generic tacrolimus formulation (Tacrobell®), there were no significant differences in the incidence or severity of patient-reported AEs between the 2 groups [36]. However, subclinical acute allograft rejection rates were more frequently observed in patients receiving generic tacrolimus compared to Prograf® (14.8 vs. 3.2%, p = 0.04).

Investigations of Heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses comparing the brand drug with each generic formulation could only be performed for cyclosporine, and with 2 generic formulations, Cicloral® and Sigmasporin Microral®. In the 4 crossover trials and sub-studies, comparing Cicloral® to Neoral® [19, 20], Cicloral® did not meet the FDA criteria for bioequivalence with respect to the Cmax (pooled Cmax T/R ratio 0.82; 90% CI 0.78–0.86; p = 0.001; online suppl. efig. 4). Data on AUC(0–t) were not available. There was no significant difference between Cicloral® and Neoral® with respect to Tmax (pooled WMD −0.05; 95% CI −0.17 to 0.08; online suppl. efig. 6) and T1/2 (pooled WMD −0.05; 95% CI −0.36 to 0.25; online suppl. efig. 7).

In the 3 crossover trials comparing Sigmasporin Microral® to Neoral® [23,24,30], Sigmasporin Microral® met the FDA criteria for bioequivalence in terms of Cmax (pooled Cmax T/R ratio 0.96; 90% CI 0.90–1.02; online suppl. efig. 4) and AUC(0–t) (pooled T/R ratio 0.95; 90% CI 0.89–1.02; p = 0.94; online suppl. efig. 5), but there was no significant difference with respect to Tmax (pooled WMD −0.13; 95% CI −0.44 to 0.18; online suppl. efig. 6) and T1/2 (pooled WMD −0.24; 95% CI −0.82 to 0.33; online suppl. efig. 7).

Discussion

In the present systematic review, we summarize the existing literature on the bioavailability of generic immunosuppressive drugs relative to their brand counterparts in healthy subjects, and their efficacy and safety in kidney transplant recipients. Most of the included reports focused on cyclosporine, followed by tacrolimus and MMF. None of the immunosuppressive drugs identified in this synthesis are currently approved for use in the United States except for 2 generic formulations of cyclosporine, Equoral® and Gengraf®. To examine relative bioavailability, however, we followed the FDA guidance by comparing the rate (Cmax) and extent (AUC(0–t)) of absorption of generic formulations available worldwide relative to their brand counterparts. We also examined the efficacy and safety of generic cyclosporine formulations relative to the brand cyclosporine Neoral®. Limited data precluded similar analyses for tacrolimus and MMF. Generic formulations of cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and MMF met the FDA requirement for bioequivalence against their respective brand counterparts on the basis of the 90% CI of 0.80–1.25 for the T/R drug’s Cmax and AUC(0–t). However, substantial heterogeneity was observed. In subgroup analyses, the Cmax achieved by Cicloral® relative to Neoral® did not meet the FDA criteria for bioequivalence, raising concerns about its pharmacokinetic profile. In terms of efficacy and safety, generic cyclosporine formulations appeared non-inferior to Neoral® in kidney transplant recipients; however, the results were deemed inconclusive due to the wide confidence limits around the effect estimates.

Although cheaper than their brand counterparts, there is controversy as to whether reduced cost of generic immunosuppressive drugs translates into lower healthcare costs [38]. A study of incident kidney transplant recipients found that first-year costs were significantly higher in patients receiving generic cyclosporine, compared to those treated with brand cyclosporine, due to dose escalation or addition of another immunosuppressant [7]. Based on the variable absorption profile of generic drugs in certain populations, we can only speculate as to whether certain characteristics such as ethnicity must be considered when choosing a generic drug, and policies might be required to better specify the target population where the generic drug could safely be used according to results of bioequivalence studies.

Controversy regarding the use of generic immunosuppressive drugs has impacted patients’ perceptions. Clinical equivalency of generic medications is accepted by 75% of patients maintained on generic substitutes and only 54% by those maintained on brand drugs [39]. However, a survey of kidney transplant recipients found that 75% did not know whether they were taking generic substitutes, yet 84% felt that generic substitutes were not consistently equivalent to their brand counterparts [40].

Among the multiple potential factors that can impact outcomes in patients receiving immunosuppressants, pharmaceutical inter- and intra-batch heterogeneity is a major safety and efficacy concern for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index. Although generic substitutes in the United States currently comply with the 90% CI range of 80–125% to satisfy bioequivalence for Cmax and AUC(0–t), intra-patient variability in serum trough levels of generic immunosuppressive drugs has been observed in kidney transplant recipients with impact on allograft related outcomes [41, 42]. Canada and Europe have implemented policies to reduce pharmaceutical heterogeneity of drugs with a narrow therapeutic index by narrowing the 90% CI range of the AUC(0–t) for generic drug approval to 90–111%.

Our results are in agreement with a recently published meta-analysis that included randomized controlled trials and observational studies [43]. The authors examined bioequivalence of generic to brand immunosuppressive drugs by comparing 2 pharmacokinetic parameters, the AUC(0–t) and Cmax. There were only 2 trials (a parallel arm and a cross-over trial) of MMF to allow for a pooled analysis. Cross-over and parallel-arm trials were also combined, and one trial had a questionable randomization procedure [44].

Strengths of our synthesis include a comprehensive literature search and rigorous analytical methods. For the study of bioequivalence, we included only crossover trials deemed compliant with the FDA guidelines. The trials enrolled healthy subjects from several countries and of variable ethnicity. For several pharmacokinetic parameters, there was no significant heterogeneity, justifying the aggregation of the data. An important limitation is the relatively small number of trials, and the inability to extrapolate data derived from healthy volunteers to kidney transplant recipients. Chronic kidney disease is associated with altered intestinal transport mechanisms, which can affect the oral bioavailability of immunosuppressive drugs [45]. and increase the risk for adverse reactions [46]. Furthermore, we included studies of populations from different regions of the world, including Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. This variability likely contributed to the heterogeneity in the bioavailability study results, as drug absorption and metabolism is affected by race, ethnicity and genetic factors. Finally, there were very few parallel-arm trials of efficacy and safety, and cyclosporine was the only drug where results could be pooled.

In conclusion, the use of generic immunosuppressive drugs for kidney transplantation remains a debatable issue with varying views regarding their bioequivalence, efficacy, and safety. The evidence surrounding the bioequivalence of generic cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and MMF indicate that their generic counterparts with the exception of Cicloral® appear to have similar bioavailability in healthy volunteers. However, none of the generic drugs tested in these bioavailability studies is currently approved for use in the United States. While the efficacy and safety of generic cyclosporine in kidney transplant recipients suggest non-inferiority to its brand counterpart, the evidence is inconclusive and this drug has become less relevant in the modern era of organ transplantation, with 92% of kidney transplant recipients now being prescribed tacrolimus as the first-line calcineurin inhibitor [47]. Practicing clinicians should be aware of the variable rate and extent of absorption that generic immunosuppressive drugs might display, and as a result, monitor serum drug levels frequently, and be alert of potential AEs that might occur due to differences in absorption rates. Moreover, adoption of stricter regulatory guidelines for approving generic drugs with a narrow therapeutic index might increase their efficacy and safety.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the technical assistance of Catherine Guarcello, MS (Stohlman Library, St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center, Boston, Mass., USA).

Support

This project was supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH, grant UL1 TR001064. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no other relevant financial interests.

References

- 1.US Renal Data System: USRDS 2013 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States: National Institutes of Health. Bethesda, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gill JS, Tonelli M: Penny wise, pound foolish? Coverage limits on immunosuppression after kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:586–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denhaerynck K, Dobbels F, Cleemput I, et al. : Prevalence, consequences, and determinants of nonadherence in adult renal transplant patients: a literature review. Transpl Int 2005; 18: 1121–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nevins TE, Kruse L, Skeans MA, Thomas W: The natural history of azathioprine compliance after renal transplantation. Kidney Int 2001;60:1565–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Generic Pharmaceutical Association: Annual Report. 2014. http://www.gphaonline.org/ (accessed March 25, 2015).

- 6.Burckart GJ, Venkataramanan R, Ptachcinski RJ, et al. : Cyclosporine absorption following orthotopic liver transplantation. J Clin Pharmacol 1986;26:647–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helderman JH, Kang N, Legorreta AP, Chen JY: Healthcare costs in renal transplant recipients using branded versus generic ciclosporin. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2010;8:61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tesi R: SangCya (Cyclosporine Oral Solution) Dear Healthcare Professional Letter, July 2000. http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHuman-MedicalProducts/ucm175740.htm (accessed March 25, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151:264–269, W64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guidance for Industry - Bioavailability and Bioequivalence Studies for Orally Administered Drug Products - General Considerations. US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration (FDA), 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. : The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I: Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005;5:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JP, White IR, Anzures-Cabrera J: Meta-analysis of skewed data: combining results reported on log-transformed or raw scales. Stat Med 2008;27:6072–6092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huedo-Medina TB, Sanchez-Meca J, Marin-Martinez F, Botella J: Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol Methods 2006; 11:193–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdallah TB, Ounissi M, Cherif M, et al. : The role of generics in kidney transplant: mycophenolate mofetil 500 versus mycophenolate: 2-year results. Exp Clin Transplant 2010;8: 292–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Almeida S, Filipe A, Neves R, et al. : Mycophenolate mofetil 500-mg tablet under fasting conditions: single-dose, randomized-sequence, open-label, four-way replicate cross-over, bioequivalence study in healthy subjects. Clin Ther 2010;32:556–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Avramoff A, Laor A, Kitzes-Cohen R, Farin D, Domb AJ: Comparative in vivo bioequivalence and in vitro dissolution of two cyclosporin A soft gelatin capsule formulations. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007;45:126–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Estevez-Carrizo FE, Parrillo S, Cedres M, Estevez-Parrillo FT, Rodriguez P: Comparative bioavailability of two oral formulations of mycophenolate mofetil in healthy adult Uruguayan subjects: a case of highly variable rate of drug absorption. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2010;48:621–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kees F, Bucher M, Schweda F, et al. : Comparative bioavailability of the microemulsion formulation of cyclosporine (Neoral) with a generic dispersion formulation (Cicloral) in young healthy male volunteers. Ther Drug Monit 2006;28:312–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kees F, Mair G, Dittmar M, Bucher M: Cicloral versus neoral: a bioequivalence study in healthy volunteers on the influence of a fat- rich meal on the bioavailability of cicloral. Transplant Proc 2004; 36: 3234–3238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Masri MA, Rizk S, Attia ML, Barbouch H, Rost M: Bioavailability of a new generic formulation of mycophenolate mofetil MMF 500 versus CellCept in healthy adult volunteers. Transplant Proc 2007;39:1233–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathew P, Mandal J, Patel K, et al. : Bioequivalence of two tacrolimus formulations under fasting conditions in healthy male subjects. Clin Ther 2011;33:1105–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mendes GD, de Oliveira CH, Sucupira M, Donato JL, Moreno RA, De Nucci G: Cyclosporine bioequivalence study: quantification using fluorescence polarization immunoassay (FPIA) and radioimmunoassay (RIA). Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2004;42:125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Najib NM, Idkaidek N, Adel A, et al. : Comparison of two cyclosporine formulations in healthy middle eastern volunteers: bioequivalence of the new Sigmasporin Microoral and Sandimmun Neoral. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2003;55: 67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park K, Kim YS, Kwon KI, Park MS, Lee YJ, Kim KH: A randomized, open-label, two-period, crossover bioavailability study of two oral formulations of tacrolimus in healthy Korean adults. Clin Ther 2007;29:154–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel S, Chauhan V, Mandal J, et al. : Single-dose, two-way crossover, bioequivalence study of Mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg tablet under fasting conditions in healthy male subjects. Clin Ther 2011;33:378–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saavedra SI, Sasso AJ, Quinones SL, et al. : [Relative bioavailability study of two oral formulations of mycophenolate mofetil in healthy volunteers]. Rev Med Chil 2011; 139: 902–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sachdeva A, Gulat R, Gupta U, Bapna JS: Comparative bioavailability of two brands of cyclosporin. Indian J Pharmacol 1997;29: 135–137. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Talaulikar GS, Srishyla MV, Job V, Selvakumar R, Thomas PP: Testing switchability of a new microemulsion formulation of cyclosporine. Transplant Proc 2003;35:2899–2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanasescu C, Serbanescu A, Spadaro A, Jen LH, Oliani C: Comparison of two microemulsion of cyclosporine A in healthy volunteers. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 1999;3:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu Y, Mao M, Wang L, Jiang X: [Bioequivalence research of cyclosporin soft capsules]. Sheng Wu Yi Xue Gong Cheng Xue Za Zhi 2012;29:311–314, 331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khatami SM, Taheri S, Azmandian J, et al. : One-year multicenter double-blind randomized clinical trial on the efficacy and safety of generic cyclosporine (iminoral) in de novo kidney transplant recipients. Exp Clin Transplant 2013, Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim SC, Han DJ: Neoplanta as a new microemulsion formula of cyclosporine in renal transplantation: comparative study with Neoral for efficacy and safety. Transplant Proc 1998;30:3547–3548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ong LM, Lim T, Rozina G, Wong HS, Shaariah W, Ghazali A, Hooi LS, Korina R, Tan HH, Indralingam V, Tan CC MS, Teo SM, Foo SM, Liew YF, Liu WJ, Zaki M: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Conversion to Generic Cyclosporine in Stable Renal Transplant Recipients. San Francisco, Kidney Week (American Society of Nephrology), 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vitko S, Ferkl M: Interchangeability of ciclosporin formulations in stable adult renal transplant recipients: comparison of Equoral and Neoral capsules in an international, multicenter, randomized, open-label trial. Kidney Int Suppl 2010;115:S12–S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Min SI, Ha J, Kim YS, et al. : Therapeutic equivalence and pharmacokinetics of generic tacrolimus formulation in de novo kidney transplant patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013;28:3110–3119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pineyro-Lopez A, Pineyro-Garza E, Gomez-Silva M, et al. : Bioequivalence of single 100-mg doses of two oral formulations of topiramate: an open-label, randomized-sequence, two-period crossover study in healthy adult male Mexican volunteers. Clin Ther 2009;31:411–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnston A: Equivalence and interchangeability of narrow therapeutic index drugs in organ transplantation. Eur J Hosp Pharm Sci Pract 2013;20:302–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hulbert AL, Pilch NA, Taber DJ, Chavin KD, Baliga PK: Generic immunosuppression: deciphering the message our patients are receiving. Ann Pharmacother 2012; 46: 671–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al Ameri MN, Whittaker C, Tucker A, Yaqoob M, Johnston A: A survey to determine the views of renal transplant patients on generic substitution in the UK. Transpl Int 2011;24:770–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rehman S, Wen X, Casey MJ, Santos AH, Andreoni K: Effect of different tacrolimus levels on early outcomes after kidney transplantation. Ann Transplant 2014;19:68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taber DJ, Baillie GM, Ashcraft EE, et al. : Does bioequivalence between modified cyclosporine formulations translate into equal outcomes? Transplantation 2005;80:1633–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Molnar AO, Fergusson D, Tsampalieros AK, et al. : Generic immunosuppression in solid organ transplantation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2015;350:h3163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stephan A, Masri MA, Barbari A, Aoun S, Rizk S, Kamel G: A one-year comparative study of Neoral vs Consupren in de novo renal transplant patients. Transplant Proc 1998; 30:3533–3534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lemahieu WP, Maes BD, Verbeke K, Vanrenterghem YF: Alterations of CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein activity in vivo with time in renal graft recipients. Kidney Int 2004; 66: 433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dreisbach AW, Lertora JJ: The effect of chronic renal failure on drug metabolism and transport. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2008;4:1065–1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saran R, Li Y, Robinson B, et al. : US renal data system 2014 annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 2015;66(1 suppl 1):Svii, S1–S305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.