Abstract

Growing evidence suggests that peripheral factors to the brain driving neuro-inflammation could affect Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and Parkinson’s Disease (PD) severity. Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV1) infection has been associated with AD while other related viruses, including cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Bar virus and human herpesvirus 6 (HHV6), are known to infect neurons. Here we compare gene expression profiles between AD or PD patients to those afflicted with herpes viral infections as to discover novel potential neuro-inflammation pathways. We found multiple significant differentially expressed genes (DEGs) shared between AD/PD and viral infections including SESN3 which has a genetic association for increased AD risk. Pathway enrichment analysis revealed viruses shared Oxidative Stress Defense System and LRRK2 pathways with AD and PD, respectively. We further processed our data to identify novel target and drug-repurposing opportunities including anti-inflammatory therapy, immune-modulators and cholinesterase inhibitors which could lead to new therapeutics paradigms for these neurodegenerative diseases.

Subject terms: Neuroimmunology, Computational biology and bioinformatics

Introduction

Globally, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) are among the most common causes of severe and fatal dementia1. While these diseases’ pathological hallmarks are neuronal loss, extracellular senile plaques containing the peptide β amyloid, and neurofibrillary tangles for AD1,2, and the loss of neurons in the substantia nigra and elsewhere in association with the presence of Lewy bodies for PD1,3, recent data indicate that neuroinflammation is involved in the progression of both neurodegenerative disorders2,3. Neuroinflammation driven by activated microglial cells causes a vicious cycle of inflammatory reaction between microglia, astrocytes, and β-amyloid plaques leading to neuronal death1. Investigators have long suspected that pathogenic agents contribute to the onset and progression of AD and PD4,5. However, only recently it was demonstrated that increased concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines occur in the initial stages of neurodegenerative diseases6. Moreover, certain genetic variants in the chromosome 6 region that specifies immune response human leukocyte antigens (HLAs)7 are associated with PD.

Peripheral viral infections could elicit brain dysfunction through direct cytolytic effects on site or through whole body circulating inflammatory reactions8. Neurotropic viruses, such as arboviruses, influenza viruses and herpes viruses developed escape mechanisms from host immune surveillance enabling access to the central nervous system (CNS) which can result in long-lasting subclinical infections (reviewed in9). The systemic and local responses of the immune system to viral infection potentially contribute to neuronal damage, even in the absence of cell death9. Viruses can elicit CNS inflammation either by traversing a comprised Blood Brain Barrier (BBB), infecting peripheral nerves or broadly over-activating the peripheral innate and adaptive host immune system10.

Multiple studies report the association between Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV1) and Alzheimer’s disease5,11,12. Other members of the Herpesviridae family have been implicated, particularly EBV, CMV and HHV613–16. Several viruses are capable of latent residency in the peripheral nervous system and target, in acute cases of encephalitis (for HSV1/2 and EBV), the same regions of the central nervous system (temporal and frontal cortex, and hippocampus) affected in AD17.

In this study, we hypothesize that comparisons of gene expression profiles from patients afflicted with either AD or PD with those profiles resulting from Herpesviridae infection, specifically CMV, EBV or HHV6, might reveal new associated neuro-inflammation pathways. We performed direct transcriptome profile comparisons between gene expression changes and enriched pathways in patients with Herpesviridae viral infection and AD/PD patients. To prioritize individual targets and pharmacological opportunities of intervention, we leveraged additional biological information such as human genetic disease associations and drug-repurposing analyses. We report here multiple human host genes and pathways that were significantly shared by human immune system responses to viral infections and neurodegenerative pathology.

Results

Data set selection

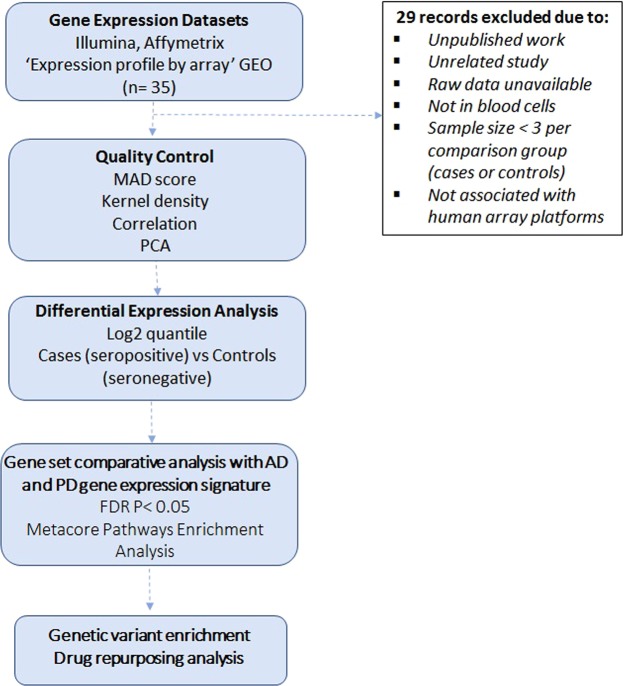

As described in detail in Methods, our computational analyses involved six steps (Fig. 1): (1) NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database querying and selection of AD and PD and CMV, EBV and HHV6 infection datasets; (2) stringent quality control and normalization for each dataset (Table S1); (3) differential expression analysis of individual datasets for healthy controls versus diseased individuals; (4) comparisons of differential expressed genes (DEGs) and pathways enriched across AD, PD and viral infection profiles; (5) integration of genetic associations and tissue-specific gene expression data integration and (6) target repositioning hypotheses generation using EMBL-EBI ChEMBL and Connectivity Map (CMAP) databases.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the cross-neurodegeneration (Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease) and cross-viral infection (CMV, EBV and HHV6) transcriptome analysis pipeline. The computational analyses consist of six major steps which were presented in the blue boxes. Detailed criteria for each major step were described in the Methods.

We found 35 GEO datasets with gene expression profiles by microarrays for AD, PD and human host response to CMV, EBV and HHV6 (Table S1). We recalculated fold changes for AD and PD, and results are comparable with previous studies18,19. Based on the filtering criteria described in the Methods section, six datasets were selected (Table 1): GSE636063 (132 whole blood samples from healthy vs 135 AD patients18), GSE99039 (whole blood samples from 232 healthy vs 204 PD patients19), GSE81246 (peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from 24 patients with latent CMV infection vs 10 patients with active disease20), GSE2020021 and GSE4582922 (7 B cell independent samples vs 7 EBV infected samples), and GSE40396 (22 whole blood samples from seronegative patients vs 10 patients seropositive for HHV6 with fever23). Table S1 summarizes all retrieved datasets along with the reasons for their inclusion or exclusion from our analyses.

Table 1.

List of patient blood and in vitro B cells infected with EBV gene expression datasets selected in this study, and the number of samples and DEGs in each dataset.

| Dataset | Phenotype | Cell type | PMID | Platform | Samples | DEGs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | Outliers | ||||||

| GSE63063 | Alzheimer’s Disease | Whole Blood | 26343147 | Illumina | 134 | 132 | 6 | 906 |

| GSE99039 | Parkinson’s Disease | Whole Blood | 28916538 | Affymetrix | 204 | 232 | 2 | 939 |

| GSE81246 | CMV host response | PBMCs | 28031361 | Affymetrix | 10 | 24 | 0 | 1910 |

| GSE20200 | EBV host response | B cells | 21147465 | Exon Array | 4 | 4 | 0 | 1491 |

| GSE45829 | EBV host response | B cells | 23724103 | Exon Array | 3 | 3 | 0 | 8589 |

| GSE40396 | HHV6 host response | Whole Blood | 23858444 | Illumina | 10 | 22 | 0 | 545 |

For each transcriptome dataset, we first determined the statistical significance of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) within each study by comparing disease to control samples. Subsequently, we compared individual study lists of significant DEGs to determine shared patterns in gene expression profiles for individual viruses compared to AD (Fig. 2A) and PD (Fig. 2B). This approach minimized any potential biases due to study differences in platforms or blood cell types.

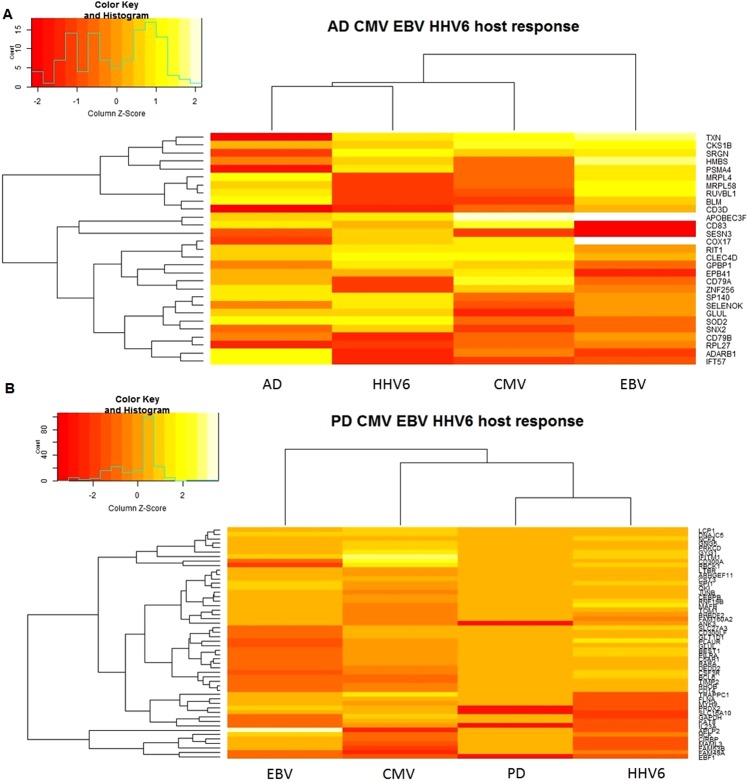

Figure 2.

Heatmaps of subset of CMV, EBV and HHV6 DEGs shared with AD (A) and PD (B). For each DEG, log2 fold changes were indicated in the heatmap. The genes were clustered using the UPGMA method.

CMV infection and Alzheimer’s disease shared molecular markers

We identified 906 and 1,910 significant (False Discovery Rate adjusted [FDR-adj.] p-value < 0.05) DEGs in relation to AD and CMV human host response, respectively. Overall, 68 DEGs were shared in AD and CMV response signatures (Hypergeometric p-value (PHyper) = 1.5 × 10−7; Table S2). SESN3 was the most down-regulated gene in patients infected with CMV and in active disease status (CMV: Fold Change [FC] = −2.7, FDR-adj. p-value = 6.3 × 10−11; AD: FC = −1.3, FDR-adj. p-value = 5.0 × 10−4, Fig. 2A). Sestrin 3 controls intracellular response to reactive oxygen species24 and acts as a trans-acting genetic regulator of a pro-convulsant gene network in the human epileptic hippocampus25.

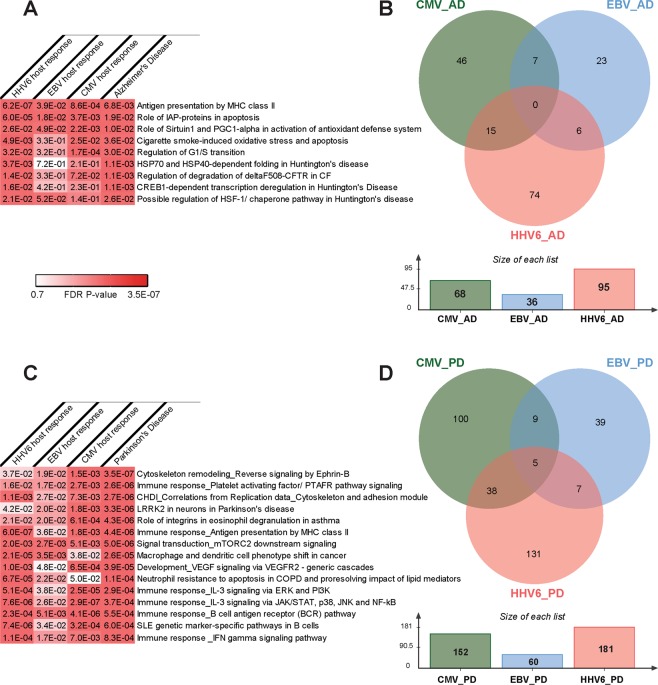

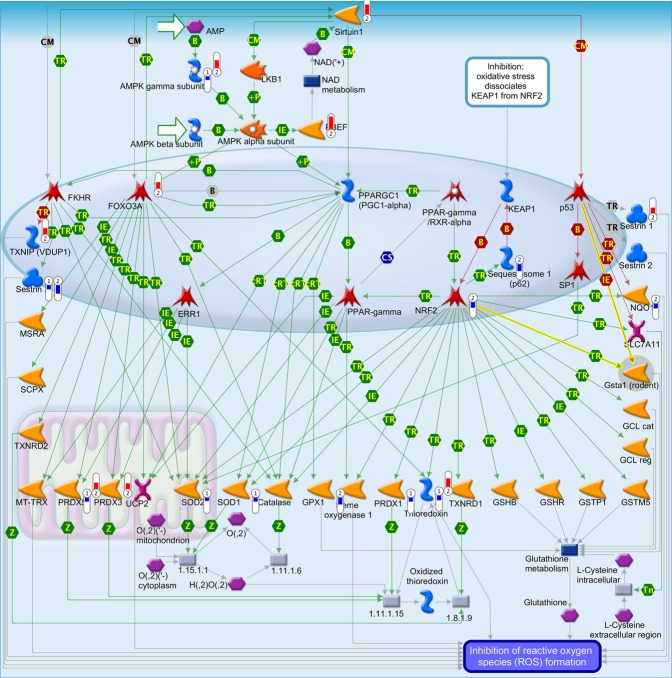

The full list of significant DEGs associated with AD and CMV (906 and 1,910 DEGs respectively) were analyzed for enriched functional pathways using MetaCore/MetaBase (GeneGo) v6.0 (Thomson Reuters, https://portal.genego.com/). In total, 5 human canonical pathways were significantly enriched in both AD and CMV DEG lists (Fig. 3A). The most significant pathway was “Role of Sirtuin1 and PGC1-alpha in activation of antioxidant defense system” (Fig. 4) (AD: FDR-adj. p-value = 0.01; CMV: FDR-adj. p-value = 2.1 × 10−3).

Figure 3.

Statistically significant (adjusted FDR p-value ≤ 0.05) shared CMV, EBV and HHV6 human host response pathways and differentially expressed genes in AD (A,B) and PD (C,D), respectively.

Figure 4.

Pathway map for “Role of Sirtuin1 and PGC1-alpha in activation of antioxidant defense system”. Significant up-regulation of genes is denoted as up-pointing bars colored in red, and significant down-regulation of genes is denoted as down-pointing bars colored in blue. The height of the colored bar represents to the magnitude of the gene expression changes (fold change) between cases and controls.

EBV infection and Alzheimer’s Disease shared molecular markers

We found 802 DEGs which were associated with EBV human host response. Of those, 36 genes were shared in AD and EBV host response signatures (PHyper = 2.0 × 10−3; Table S3). As in CMV host response comparison with AD transcriptional profiles, SESN3 ranked as one of the top 20 genes associated with EBV human host response with same direction of association as seen in CMV human host response (EBV: FC = −6.9, FDR-adj. p-value = 1.1 × 10−4) (Fig. 2A).

Five canonical signaling pathways were enriched in both AD and EBV (Fig. 3A). Similar to that observed for CMV infection, the pathways “Role of Sirtuin1 and PGC1-alpha in activation of antioxidant defense system” (AD: FDR-adj. p-value = 0.01; EBV: FDR-adj. p-value = 0.049) and “Antigen presentation by MHC class II” were most significantly enriched in AD and EBV infection (AD: FDR-adj. p-value = 6.8 × 10−3; CMV: FDR-adj. p-value = 0.04).

HHV6 infection and Alzheimer’s Disease shared molecular markers

We identified 1,698 genes associated with HHV6 human host response. Comparisons of transcriptional profiles yielded 95 genes shared in AD and HHV6 host response (PHyper = 0.038; Table S4). IDO1 ranked as the top gene associated with HHV6 response (HHV6: FC = 4.5, FDR adj. p-value = 5.3 × 10−5; AD: FC = −1.08, FDR adj. p-value = 0.001, Fig. 2A). Indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase (IDO1) catalyzes the first and rate limiting step in the kynurenin pathway26, which has been implicated in neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration27,28.

For AD and HHV6 (906 and 1,698 DEGs respectively), there were 9 common significantly enriched canonical pathways of which “Antigen presentation by MHC class II” had the highest significance (AD: FDR-adj. p-value = 6.8 × 10−3; CMV: FDR-adj. p-value = 6.2 × 10−6) (Fig. 3A).

Common genes and pathways across multiple viruses and Alzheimer’s Disease

We identified 28 genes that were associated with AD and host response to at least two of the three viruses investigated in this study (CMV, EBV or HHV6) (Fig. 3B). Thioredoxin (TXN) was the most down-regulated gene in patients with AD (FC = −1.44, FDR adj. p-value = 1.20 × 10−3), while up-regulated in patients with CMV (FC = 2.7, FDR adj. p-value = 3.0 × 10−4) and HHV6 active infection (FC = 1.51, FDR adj. p-value = 2.4 × 10−3) (Fig. 2A). Thioredoxin is crucial in maintaining a reduced oxygen intra-cellular environment and thus renders protection against oxidative stress29. For this reason, thioredoxin has been considered a promising early biomarker in the diagnosis of AD, suggesting the potential involvement of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of the disease30.

Three pathways were significantly enriched in all host response viruses and AD datasets: “Antigen presentation by MHC class II”, “Role of IAP-proteins in apoptosis” and “Role of Sirtuin1 and PGC1-alpha in activation of antioxidant defense system” (Fig. 3A, Table S5). Two other pathways enriched in CMV and HHV6 host response as well as AD were “Induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in airway epithelial cells” and “Regulation of G1/S transition”.

CMV infection and Parkinson’s Disease shared molecular markers

There were 939 genes associated with PD and 1910 genes associated with CMV host response. Of those, 152 DEGs were shared between PD and CMV host response (PHyper = 0.04; Table S6). Amyloid beta precursor like protein 2 (APLP2) was the most up-regulated gene in CMV host response (FC = 8.8, FDR adj. p-value = 4.1 × 10−7) and was also associated with PD (FC = 1.13, FDR adj. p-value = 3.6 × 10−3) (Fig. 2B). APLP2 belongs to the Alzheimer’s-associated amyloid beta-protein precursor gene family, which interacts with the synaptic release machinery, suggesting a role in neurotransmission31.

We found 28 canonical signaling pathways enriched in both PD and CMV using the full list of significant DEGs. The most significant pathways were “Integrin inside-out signaling in neutrophils” (PD: FDR-adj. p-value = 4.1 × 10−11; CMV: FDR-adj. p-value = 3.0 × 10−3) and “Inhibition of neutrophil migration by pro-resolving lipid mediators” (PD: FDR-adj. p-value = 4.1 × 10−11; CMV: FDR-adj. p-value = 3.4 × 10−3; Fig. 3C).

EBV infection and Parkinson’s Disease shared molecular markers

Comparisons of transcriptional profiles yielded 60 genes shared in PD and EBV host response (PHyper = 0.02; Table S7). As seen in the CMV host response comparison with PD transcriptional profiles, APLP2 ranked as one of the top 5 genes associated with EBV human host response (EBV: FC = −6.5, FDR-adj. p-value = 1.2 × 10−4; Fig. 2B).

From the list of genes associated with PD and EBV (939 and 802 DEGs respectively), there were 53 pathways significantly enriched in both diseases with “Reverse signaling by Ephrin-B” as the most significant one (PD: FDR-adj. p-value = 3.8 × 10−7; EBV: FDR-adj. p-value = 5.4 × 10−3; Fig. 3C).

HHV6 infection and Parkinson’s Disease shared molecular markers

Overall, 181 DEGs were shared in PD and HHV-6 response signatures (PHyper = 6.4 × 10−9; Fig. 2B; Table S8). IL1RN was the most highly over-expressed gene in patients infected with HHV6 and significantly expressed in PD (HHV6: FC = 8.47, FDR-adj. p-value = 1.7 × 10−6; PD: FC = 0.27, p-value = 1.7 × 10−3). Interleukin 1 (IL-1) receptor antagonist (IL-1RN) is a naturally occurring anti-inflammatory agent that binds to the IL-1 receptor but lacks agonist activity and therefore functions like a competitive inhibitor of IL-132.

Considering the total genes associated with PD and HHV6 (939 and 1697 DEGs respectively), 253 human canonical pathways significantly enriched in both DEG lists. As seen for CMV, the pathway entitled “Inhibition of neutrophil migration by pro-resolving lipid mediator” ranked as the most significant result (PD: FDR-adj. p-value = 4.3 × 10−11; EBV: FDR-adj. p-value = 3.0 × 10−3).

Common genes and pathways across multiple viruses and Parkinson’s Disease

We identified 54 genes associated with PD and host response to at least two of the three viruses investigated in this study (CMV, EBV or HHV6) (Fig. 3D). BCL6, GYG1, RBCK1, TIMP2 and CIRBP were common DEGs across all viruses tested and associated with PD. Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) are endogenous inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and the aberrant expressions of MMPs are strongly associated with neuroinflammation and neuronal cell death33.

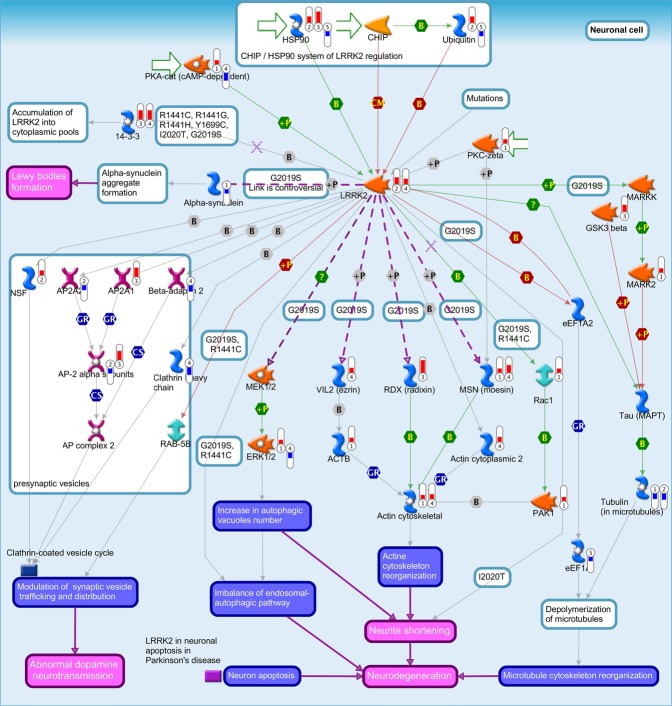

In total, 15 human canonical pathways were significantly enriched from DEGs associated with PD and human host response to CMV, EBV and HHV6; many of which are involved in host immune response (Table S9). The most significant pathway was “Reverse signaling by Ephrin-B” (PD FDR-adj. p-value = 3.3 × 10−6; HHV6 FDR-adj. p-value = 3.7 × 10−2; EBV FDR-adj. p-value = 1.9 × 10−2; CMV FDR-adj. p-value = 1.5 × 10−3). Previous studies have indicated that ephrin signaling pathway is involved in the inflammatory process following CNS injury by serving roles in the maintenance of endothelial junction integrity and cytoskeletal structure. Remarkably, there was significant enrichment for several pathways commonly associated with PD and neurodegenerative diseases in general. These include the leucine rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) pathway (PD FDR-adj. p-value = 3.7 × 10−6; HHV6 FDR-adj. p-value = 4.2 × 10−2; p-value = EBV FDR-adj. p-value = 2.0 × 10−2; CMV FDR-adj. p-value = 1.8 × 10−3; Fig. 5). The G2019S mutation within the LRRK2 kinase domain is the most common causal mutation in PD patients34, and it results in substantial increase in LRRK2 kinase activity35. The mechanism by which LRRK2-G2019S induces PD pathology remains unclear, although several studies have implicated this mutation in the dysregulation of autophagic function36.

Figure 5.

Pathway map for “LRRK2 in neurons in Parkinson’s disease”. Significant up-regulation of genes is denoted as up-pointing bars colored in red, and significant down-regulation of genes is denoted as down-pointing bars colored in blue. The height of the colored bar represents to the magnitude of the gene expression changes (fold change) between cases and controls.

Control analyses for disease relevance of detected molecular signatures

To evaluate potential biases in our approach, we performed further analyses. First, we also compared CMV, EBV and HHV6 host response DEGs to genes associated with Huntington’s Disease (HD) and Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM; FDR adj. p-value ≤ 0.05), as control analyses with another neurodegenerative condition (HD) and a disease unrelated to neurodegenerative and infectious disease (T2DM), to examine for potential spurious comparisons. We selected three publicly available datasets with peripheral blood gene expression samples: GSE900637 (11 children diseased for T2DM and 23 healthy children), GSE6952838 (23 adults diseased for T2DM and 27 healthy controls) and GSE3472139 (150 samples from patients with HD and 70 samples from healthy controls). By contrast with the comparisons with AD and PD, these control analyses showed no statistically significant enrichment with T2DM or HD in the 3 datasets tested (PHyper > 0.1, Fig. S1) which suggests that our common molecular signatures between AD or PD and Herpesviridae infections are robust and non-spurious.

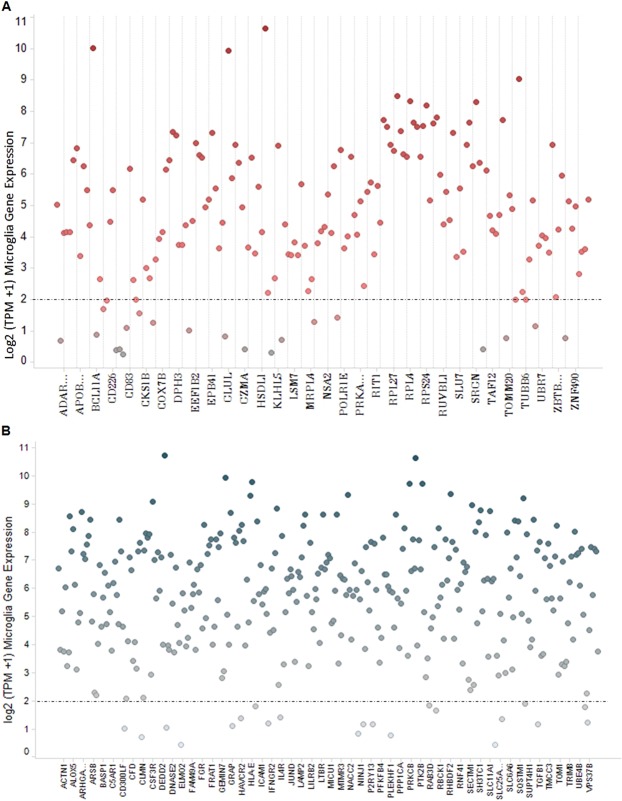

Second, since the gene expression datasets used in our analyses were obtained from blood samples of AD and PD patients we needed to evaluate the co-expression of shared viral host response genes with the most important immune function cell type found in the brain, the microglia. We re-analyzed and evaluated the gene expression profiles of 161 CMV, EBV or HHV6 host response genes shared with AD, and 329 genes shared with PD in 37 human microglia post-mortem samples, whose donors had history of normal cognitive function and no apparent neuropathological abnormalities40 (Fig. 6). We found the majority of genes (139 of 161 genes) 86.3% in AD and (308 of 329 genes) 93.6% in PD were actively expressed in human microglia (log2 TPM > 2) (Fig. 6). Of the DEGs shared by at least two of the three viruses, we found 82.1% (23 out of 28 genes) in AD and 90.7% (49 out of 54 genes) in PD were expressed in microglia. These findings lend further support for sampling of the blood as a surrogate for direct microglia gene expression profiling.

Figure 6.

Microglia gene expression levels (log2 transcripts per million reads (TPM)) of CMV, EBV and HHV6 DEGs common with AD (A) or PD (B).

Potential drug targets with human genetic evidence

It was previously reported that drug targets with robust human genetics support regarding disease pathology could boost success rates in clinical development41. Therefore, we surveyed the public genome-wide association studies present in the GWAS catalog for genetic evidence for the 172 and 329 DEGs that associated with host response to viruses (CMV, EBV or HHV6) and AD or PD, respectively. Each SNP was interposed to the linkage disequilibrium (LD) region upstream/downstream within 1 kb of the DEG coding region. A total of 19 genes were proximal to at least one SNP associated with neurodegenerative diseases (AD: 11 genes PD: 8 genes) (Table 2). Rs6430538, the most significant variant (p-value = 8 × 10−24) associated with PD, is located near the gene HNMT on chromosome 2. HNMT encodes histamine N-methyltransferase which has a key leading role in histamine metabolism in the central nervous system42, and was pointed as a genomic biomarker for PD increased susceptibility43. Rs2373115, an intronic variant near GRB2 associated binding protein 2 (GAB2), was the most significant variant (p-value = 1 × 10−10) associated with AD. Multiple genetic variants in the GAB2 region are associated with late-AD onset, which could be involved in multiple pathways leading to the formation of neurofibrillary tangles44.

Table 2.

List of 19 DEGs associated with viral host response and Alzheimer’s Disease or Parkinson’s Disease proximal to SNPs associated with neurodegenerative diseases in the GWAS catalog.

| DEG | Gene Description | EBV DEG | CMV DEG | HHV6 DEG | Disease associated | Most significant variant | P-value | PUBMED IDs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HNMT | histamine N-methyltransferase | x | Parkinson’s disease | rs6430538 | 8.00E-24 | 28892059; 25064009; 22451204 | ||

| SIPA1L2 | signal induced proliferation associated 1 like 2 | x | Parkinson’s disease | rs10797576 | 8.00E-13 | 28892059 | ||

| RAB29 | RAB29, member RAS oncogene family | x | Parkinson’s disease | rs947211 | 2.00E-12 | 19915576 | ||

| ZNF626 | zinc finger protein 626 | x | Alzheimer’s disease | rs561655 | 7.00E-11 | 21460841 | ||

| GAB2 | GRB2 associated binding protein 2 | x | Alzheimer’s disease | rs2373115 | 1.00E-10 | 17553421 | ||

| VRK1 | vaccinia related kinase 1 | x | Alzheimer’s disease | rs150511909 | 4.00E-09 | 26830138 | ||

| MRPL58 | mitochondrial ribosomal protein | x | x | Alzheimer’s disease | rs9899728 | 2.00E-08 | 26913989 | |

| CLMN | calmin | x | Alzheimer’s disease | rs115102486 | 2.00E-08 | 26830138 | ||

| PLEKHM1 | pleckstrin homology and RUN domain containing M1 | x | Parkinson’s disease | rs11012 | 6.00E-08 | 20070850 | ||

| SESN3 | sestrin 3 | x | x | Alzheimer’s disease | rs3911569 | 3.00E-07 | 26830138 | |

| ADRM1 | adhesion regulating molecule 1 | x | Alzheimer’s disease | rs73310256 | 3.00E-07 | 26830138 | ||

| MX2 | MX dynamin like GTPase 2 | x | Parkinson’s disease | rs78736162 | 3.00E-07 | 25663231 | ||

| ACTN4 | actinin alpha 4 | x | Parkinson’s disease | rs62120679 | 6.00E-07 | 28892059 | ||

| SQSTM1 | sequestosome 1 | x | Alzheimer’s disease | rs72807343 | 7.00E-07 | 24162737 | ||

| RAB3D | RAB3D, member RAS oncogene family | x | Alzheimer’s disease | rs148273964 | 8.00E-07 | 26830138 | ||

| RAB11FIP4 | RAB11 family interacting protein 4 | x | Alzheimer’s disease | rs142835438 | 8.00E-07 | 27770636 | ||

| STAP1 | Signal transducing adaptor family member 1 | x | Parkinson’s disease | rs2242330 | 2.00E-06 | 17052657 | ||

| IER2 | immediate early response 2 | x | Alzheimer’s disease | rs72998574 | 2.00E-06 | 27770636 | ||

| GRN | granulin precursor | x | Parkinson’s disease | rs63750043; g.103432 C > T | NA | 17923627 |

In addition, we identified several SNPs in close proximity (<1 KB to the coding region) of the 172 and 329 DEGs showed genetic association with other non-relevant conditions to neurodegenerative diseases. For example, 20 genes were proximal to SNPs associate with T2DM (Table S10).

Drug repurposing analysis

The 401 targets identified in this study (172 and 329 DEGs associated with host response to viruses and AD and PD, respectively) were mapped to public compounds by searching the EMBL-EBI ChEMBL database for approved and marketed drugs targeting these genes. Overall, we identified 55 drug-target pairs in 20 DEGs (Table 3). Most genes were associated with multiple drugs, for example, TUBB6 was targeted by 12 unique compounds with diverse therapeutic indications such as oncology and acute coronary syndrome. Alfacalcidol, a vitamin D receptor (VDR) agonist with therapeutic indication for PD is also included in our list as a potential repurposing opportunity to treat peripheral drivers of neurodegeneration.

Table 3.

List of launched drugs targeting DEGs associated with viral host response and Alzheimer’s Disease or Parkinson’s Disease.

| Target | EBV_DEG | CMV_DEG | HHV6_DEG | Drug | Disease | Molecule type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VDR | x | ALFACALCIDOL | diabetic nephropathy | Small molecule | ||

| VDR | x | CHOLECALCIFEROL | type I diabetes mellitus; Parkinson’s Disease | Small molecule | ||

| VDR | x | CALCIPOTRIENE | psoriasis | Small molecule | ||

| VDR | x | ERGOCALCIFEROL | acute coronary syndrome | Small molecule | ||

| VDR | x | PARICALCITOL | chronic kidney disease | Small molecule | ||

| VDR | x | CALCITRIOL | Hypocalcemia | Small molecule | ||

| VDR | x | DOXERCALCIFEROL | secondary hyperparathyroidism | Small molecule | ||

| VDR | x | CALCIFEDIOL | secondary hyperparathyroidism | Small molecule | ||

| TYMP | x | TIPIRACIL | metastatic colorectal cancer | Small molecule | ||

| TUBB6 | x | VINCRISTINE | acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Small molecule | ||

| TUBB6 | x | DOCETAXEL | squamous cell carcinoma | Small molecule | ||

| TUBB6 | x | PACLITAXEL | breast carcinoma | Small molecule | ||

| TUBB6 | x | COLCHICINE | acute coronary syndrome | Small molecule | ||

| TUBB6 | x | VINORELBINE | breast carcinoma | Small molecule | ||

| TUBB6 | x | TRASTUZUMAB EMTANSINE | breast carcinoma | Antibody | ||

| TUBB6 | x | BRENTUXIMAB VEDOTIN | lymphoma | Antibody | ||

| TUBB6 | x | CABAZITAXEL | prostate carcinoma | Small molecule | ||

| TUBB6 | x | VINBLASTINE | neoplasm | Small molecule | ||

| TUBB6 | x | ERIBULIN | breast carcinoma | Small molecule | ||

| TUBB6 | x | VINFLUNINE | neoplasm | Small molecule | ||

| TUBB6 | x | IXABEPILONE | neoplasm | Small molecule | ||

| TOP1MT | x | TOPOTECAN | acute myeloid leukemia | Small molecule | ||

| RARA | x | x | TRETINOIN | acne | Small molecule | |

| RARA | x | x | ADAPALENE | acne | Small molecule | |

| RARA | x | x | ACITRETIN | psoriasis | Small molecule | |

| RARA | x | x | ISOTRETINOIN | acne | Small molecule | |

| RARA | x | x | ALITRETINOIN | Eczema | Small molecule | |

| RARA | x | x | TAZAROTENE | psoriasis | Small molecule | |

| RARA | x | x | ETRETINATE | psoriasis | Small molecule | |

| PSMB10 | x | BORTEZOMIB | multiple myeloma; Glycogen storage disease due to acid maltase deficiency | Small molecule | ||

| PSMB10 | x | IXAZOMIB CITRATE | multiple myeloma | Small molecule | ||

| PSMB10 | x | CARFILZOMIB | neoplasm | Protein | ||

| PDK3 | x | SODIUM DICHLOROACETATE | lactic acidosis | Small molecule | ||

| IL4R | x | DUPILUMAB | Eczema | Antibody | ||

| IL23A | x | x | USTEKINUMAB | psoriasis | Antibody | |

| IL17RA | x | BRODALUMAB | psoriasis | Antibody | ||

| IFNGR2 | x | INTERFERON GAMA-1B | relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis | Protein | ||

| IFNGR2 | x | INTERFERON GAMMA-1B | idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | Protein | ||

| HCK | x | BOSUTINIB | neoplasm | Small molecule | ||

| FGR | x | x | DASATINIB | chronic myelogenous leukemia | Small molecule | |

| EPHB6 | x | x | VANDETANIB | thyroid carcinoma | Small molecule | |

| EPHB6 | x | x | PREDNIMUSTINE | lymphoma | Small molecule | |

| CSF3R | x | x | PEGFILGRASTIM | breast carcinoma | Protein | |

| CSF3R | x | x | FILGRASTIM | myocardial infarction | Protein | |

| CSF3R | x | x | LIPEGFILGRASTIM | lymphoma | Small molecule | |

| CD52 | ALEMTUZUMAB | diabetes mellitus | Antibody | |||

| CD3D | x | x | BLINATUMOMAB | acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Antibody | |

| CD3D | x | x | MUROMONAB-CD3 | immune system disease | Antibody | |

| CD3D | x | x | CATUMAXOMAB | neoplasm | Antibody | |

| BCR | x | PONATINIB | neoplasm | Small molecule | ||

| ALOX5 | x | SULFASALAZINE | rheumatoid arthritis | Small molecule | ||

| ALOX5 | x | ZILEUTON | asthma | Small molecule | ||

| ALOX5 | x | MESALAMINE | ulcerative colitis | Small molecule | ||

| ALOX5 | x | BALSALAZIDE | ulcerative colitis | Small molecule | ||

| ALOX5 | x | OLSALAZINE | ankylosing spondylitis | Small molecule |

CMAP is another drug repurposing approach which deploys the anti-correlation relationship across disease gene expression signatures and pharmacological in vitro perturbations45. We performed separate analyses using CMV, EBV and HHV6 human host response gene expression signatures to assess anti-correlation of approximately 5000 small-molecule compounds and 300 reagents from the Broad Institute public library (www.broadinstitute.org/connectivity-map-cmap). Overall, 16, 24 and 16 compounds were significantly anti-correlated to the CMV, EBV and HHV6 host response signature respectively (p-value < 0.05, Specificity < 0.1; Table 4). Of those, 14 compounds (highlighted in Table 4) showed evidence in the literature of neuro-protection to Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s Disease through multiple mechanisms, such as dopamine receptor agonism, monoamine oxidase and cholinesterase inhibition. In addition, multiple compounds identified showed anti-inflammatory properties, which were previously considered potential pharmacological options for AD prevention46.

Table 4.

List of the Broad Institute public library of compounds associated with gene targets in CMV, EBV or HHV6 human host response based on CMAP45 analysis of contrary gene expression profiles.

| Compound | Mechanism of Action | Indication | CMV Host response signature | EBV Host response signature | HHV6 Host response signature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Score | Enrichment Score | P-Value | Compound Score | Enrichment Score | P-Value | Compound Score | Enrichment Score | P-Value | |||

| Quinostatin | PI3-Kinase/mTOR inhibitors | Oncology | 1.00 | −0.87 | 0.0337 | 1 | −0.94 | 0.0085 | NA | NA | NA |

| Cortisone | Corticosteroid Hormone Receptor Agonists | Anti-inflammatory | 0.50 | −0.88 | 0.0285 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Quinethazone | Sodium/chloride tranporter inhibitor | Antihypertension | 0.50 | −0.84 | 0.0492 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Metrifonate | Cholinesterase inhibitor | Neuro protection 86, 87 | 0.37 | −0.95 | 0.0054 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Cicloheximide | Protein synthesis inhibitor | Antibiotics | 0.33 | −0.99 | 0.0002 | 0.33 | −0.93 | 0.0107 | NA | NA | NA |

| Anisomycin | MAP kinase activator | Neuro protection 71 | 0.33 | −0.97 | 0.0023 | 0.33 | −0.96 | 0.0038 | NA | NA | NA |

| Molindone | Dopamine receptor antagonist | Neuro protection 69 | 0.33 | −0.94 | 0.0059 | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.90 | 0.0216 |

| Hydroflumethiazide | Na-Cl cotransporter inhibitor | Antihypertensive | 0.33 | −0.94 | 0.0077 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Pronetalol | Adrenoreceptor blocker (beta) | Neuro protection69 | 0.33 | −0.93 | 0.0089 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Picotamide | Eicosenoid receptor antagonist | Anti-inflammatory | 0.33 | −0.93 | 0.0103 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Mephenytoin | Sodium channel blocker | Antihypertensive | 0.33 | −0.89 | 0.0231 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Dipivefrine | Adrenergic agonist | Neuro protection 69 | 0.33 | −0.87 | 0.0343 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Etamsylate | Prostaglandin synthesis inhibitor | Anti-inflammatory | 0.33 | −0.85 | 0.0422 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Mebeverine | Phosphodiesterase inhibitor | Neuro protection 88 | 0.33 | −0.85 | 0.045 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Prasterone | Estrogen receptor (ER) agonists Androgen receptor (AR) agonists | Neuro protection 89 | 0.33 | −0.85 | 0.0467 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Pirenzepine | Muscarinic M1 receptor antagonist | Neuro protection 69 | 0.30 | −0.95 | 0.0045 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Calmidazolium | Calmodulin binding inhibitor | Immunosuppressant | NA | NA | NA | 1.00 | −0.9023 | 0.0193 | NA | NA | NA |

| Antazoline | Histamine H1 receptor antagonist | Allergy | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.8696 | 0.0342 | NA | NA | NA |

| Beta-escin | Vasoconstriction | Cardiovascular Agent [Pubchem] | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.7912 | 0.0181 | NA | NA | NA |

| Betahistine | Histamine H1 receptor agonist | Anti-vertigo | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.8763 | 0.0312 | NA | NA | NA |

| Cephaeline | Anti-neoplastic | Oncology | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.9537 | 0.0002 | NA | NA | NA |

| Cetirizine | Histamine H1 receptor antagonist | Allergy | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.8937 | 0.023 | NA | NA | NA |

| Dequalinium chloride | Anti-bacterial | Antibiotics | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.9666 | 0.0021 | NA | NA | NA |

| Domperidone | Dopamine receptor D2 antagonist | Antiemetic | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.8436 | 0.0495 | NA | NA | NA |

| Emetine | anti-parasitic | Anti-parasitic | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.9978 | 0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Felodipine | Calcium channel (L-type) blocker | Antihypertensive | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.6897 | 0.0066 | NA | NA | NA |

| Flunarizine | Sodium channel antagonist; Calmodulin binding and H1 antagonist | Severe Migraine | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.9181 | 0.0137 | NA | NA | NA |

| Metergoline | Serotonin and Dopamine receptors ligand | Pychoactive (Drug Bank) | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.9576 | 0.0036 | NA | NA | NA |

| Natamycin | Anti-infective agent | Anti-parasitic | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.9229 | 0.0121 | NA | NA | NA |

| Pargyline | Monoamine oxidase inhibitor | Neuro protection 87 | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.937 | 0.0081 | NA | NA | NA |

| Perhexiline | CPT inhibitor | Cardiovascular Agent [Pubchem] | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.8921 | 0.0238 | NA | NA | NA |

| Phenyl propanolamine | Adrenoreceptor agonist (alpha) | Allergy | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.9258 | 0.0113 | NA | NA | NA |

| Piribedil | Dopamine receptor agonist | Parkinson’s Treatment | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.9197 | 0.0132 | NA | NA | NA |

| Pyrvinium | Anthelmintic | Anti-parasitic | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.7906 | 0.0039 | NA | NA | NA |

| Saquinavir | HIV Protease inhibitor | Anti-retroviral | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.8712 | 0.0335 | NA | NA | NA |

| Talampicillin | Peptidoglycan synthesis inhibitor | Antibiotics | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.8465 | 0.0476 | NA | NA | NA |

| Tretinoin | Retinoid | Skin related conditions | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.4968 | 0.0017 | NA | NA | NA |

| Cyclopenthiazide | Sodium Chloride Symporter Inhibitor | Antihypertensive | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.9846 | 0.0004 |

| Alcuronium chloride | Cholinergic receptor antagonist | Muscle relaxant | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.00 | −0.956 | 0.0036 |

| Pergolide | Dopamine receptor agonist | Pychoactive (Drug Bank) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.957 | 0.0036 |

| Staurosporine | Protein kinase inhibitor | Oncology | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.00 | −0.8538 | 0.006 |

| Hemicholinium | Acetylcholine stores depletor | Neuro protection 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.9296 | 0.0094 |

| Suramin sodium | Topoisomerase inhibitor | Oncology | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.45 | −0.9171 | 0.013 |

| Pyrantel | antihelmintic | Anti-parasitic | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.9011 | 0.0191 |

| Arachidonyl trifluoromethane | Phospholipase A2 inhibitor | Anti-inflammatory | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.00 | −0.9004 | 0.0193 |

| Triprolidine | Histamine H1 receptor antagonist | Allergy | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.8889 | 0.0242 |

| Ethambutol | Chelating agent | Antibiotics | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.30 | −0.886 | 0.0255 |

| Minaprine | 5-HT2 receptor inhibitor; Dopamine receptor agonist | Parkinson’s Treatment | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.37 | −0.8763 | 0.0303 |

| Nimesulide | Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor | Anti-inflammatory | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.8728 | 0.0322 |

| Ganciclovir | DNA synthesis inhibitor | Antibiotics | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.8612 | 0.0382 |

| Sparteine | Anti-inflammatory diuretic Anti-infective agent | Anti-inflammatory | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.85 | 0.0446 |

| Pentoxifylline | Phosphodiesterase inhibitor | Intermittent Claudication | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.33 | −0.849 | 0.0454 |

Compounds with neuro protection evidence were highlighted (in bold).

Discussion

Understanding the causal basis for neurodegenerative diseases is challenged by its extended preclinical stage, and the unfeasible task to sample brain tissues routinely. Currently, it is known that neurodegenerative diseases, such as AD and PD, could result from multiple risk factors including genetic susceptibility47,48, age49, and toxins and inflammatory responses as environmental triggers for microglia and astrocyte activation50. In this context, pervasive viral infections could precipitate peripheral inflammatory reactions or immune dysregulation that are often associated with AD and PD9,36,51. We report here a systematic study of common molecular markers between viral perturbations to human immune response and clinical AD and PD. Our strategy was to examine multiple public transcriptome datasets from patients seropositive/seronegative for CMV, EBV or HHV6, and AD/PD patients with the goal of identifying novel biology mechanisms suited for therapeutic modulation.

The concept of utilizing datasets with blood samples for the detection of disease associated molecular changes in gene expression relies on the natural role of peripheral blood cells in immune response to circulating pathogens. This enabled our blood-to-blood sample gene expression comparisons between human host response to CMV, EBV or HHV-6 infection to that of AD and PD patients. In addition, recent studies demonstrated significant correlation in gene expression between multiple brain tissues and peripheral blood cells52–56. We confirmed that the majority of DEGs from the blood are also actively expressed in human microglia. Therefore, we feel there is validity in our approach of inferring genes and pathways involved in AD/PD pathology through comparative blood differential gene expression analyses with host response to viral pathogens.

Our results provide evidence of the involvement of oxidative stress mechanisms in the pathologies of our representative viruses and AD through the activation of the Sirtuin and PGC1-alpha pathway. In addition, SESN3 and TXN, which play important roles in this pathway, ranked among the top genes associated with CMV and EBV, and CMV and HHV6 host responses, respectively. Further support is provided by genetic evidence from GWAS which show an association of the SNP rs3911569 located near the gene SESN3 with a 5-fold increased risk for AD. These findings support the emerging “mitochondrial cascade hypothesis” based on growing evidence for AD-related mitochondrial dysfunction57, and the potential impact of CMV, EBV and HHV6 host response in oxidative stress.

Our analyses also highlighted BCL6, GYG1, RBCK1, TIMP2 and CIRBP, which were DEGs shared between all viruses and PD. TIMP2 was associated with neuroprotection through inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases33, which were involved in neuropathological processes such as inflammation, BBB damage and neuronal cell death, leading to multiple CNS disorders such as PD58. To our knowledge, none of the other genes have been previously linked to PD, neurodegeneration or neuroinflammation. BCL6, a sequence specific transcriptional repressor which is a key player in B cell differentiation, has recently gained attention due to the association of EBV latent proteins with BCL6 down-regulation59. These findings have implications for emerging strategies targeting B cell differentiation but how they could influence neurodegeneration still needs further investigation.

Recent studies show that LRRK2, a kinase mutated in PD clinical cases60–62, modulates inflammation in response to different pathological stimuli. LRRK2 plays a potential role in cytoskeleton remodeling and vesicle trafficking in microglia cells toward a pro-inflammatory state and, consequently, neurodegeneration63. The LRRK2 pathway was significantly enriched from DEGs associated with PD and human host response to CMV, EBV and HHV6. LRRK2 gene expression is regulated by IFN-γ and potentially mediates immune responses to pathogens64,65. Recently, we reported that this pathway was also linked to human host response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis66. LRRK2 knock-outs in mouse models, displays phenotypes of hyperactive immune responses and increased risk to inflammatory bowel disease by regulating the transcriptional regulatory protein nuclear factor of activated T cells67. Our findings further support the potential roles of LRRK2 in host response to infection and neurodegeneration.

By mapping the 401 DEGs identified in this study to compounds listed in the ChEMBL database, we identified 55 drug-target pairs for 20 genes. Of those, 12 drug-target pairs showed primary therapeutic indication for auto-immune disease or chronic inflammatory conditions, such as psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis. These results highlight the role of immune dysregulation in neurodegeneration, particularly, in AD and PD68. Thus, our findings suggest the use of immunomodulators as potential therapeutic strategies for AD and PD. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines as well as reactive oxygen and nitrogen species secreted by activated microglia can trigger a neurotoxic cascade leading to neuronal lesions and significant damage to the CNS. Therefore, therapies targeting neuroinflammation either directly or indirectly warrant further investigation68.

From our CMAP analysis, we identified several clinically used drugs that could be potentially repurposed for targeting human host factors in CMV, EBV and HHV6 infections. Overall, 14 of those compounds showed evidence in the literature of neuro-protection to AD or PD through multiple mechanisms, such as dopamine receptor agonism, and monoamine oxidase and cholinesterase inhibition69–71. Moreover, other CMAP compounds identified showed anti-inflammatory properties, many of which have shown promising results in experimental models of the disease70,72. These findings suggest several relevant mechanisms pertinent to both viral infection and neurodegeneration that need to be further explored.

Multiple epidemiological reports have associated AD or PD with diverse bacterial and viral pathogens4,5,73. Most of them connect Herpesviridae to AD, particularly HSV-174–76, EBV, CMV, and HHV613–16. In aggregate, these studies are suggestive of a viral contribution to neurodegenerative diseases although their findings offer little insight into potential mechanisms. Recently, Readhead et al.77 compared computational networks between AD and the RNA-Seq abundance of multiple viruses. Their findings implicate HHV6 and HHV7 contribution to the development of neuropathology and AD. Differently, our study provides a direct gene expression comparison of changes in expression in patients with documented evidence for viral infection (and active disease) and AD/PD. Arguably, using host gene expression signatures might be a more “agonistic” approach which overcomes the limitations of “virus hunting” for specific pathogens and could reveal the participation of both known and unknown viruses (or other pathogens) in neurodegenerative disease pathology based on overall host response.

Our study has some limitations to be considered. Most importantly, we were limited by the sample size and quality of publicly available datasets. For instance, we wished to investigate HSV-1 human host response comparing blood gene expression with the AD/PD DEGs/pathways but none of the available datasets were generated from patients. Moreover, the results presented here are not enough to conclusively prove causality relationship between viral host response and neurodegeneration. For that to occur, further clinical trials and interventional studies are necessary. Lastly, drug repurposing compounds obtained from CMAP analyses are derived from Broad Institute gene expression data on fibroblasts and tumor cell lines, which may not be the most relevant tissue for this study. Validating these results on microglia or brain tissues or even specific blood cells would be ideal.

Our study adds to the growing evidence of the role of immune dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Moreover, gene expression systematic comparisons between host response to EBV, CMV and HHV6 and AD/PD provide new insights into host genes and pathways important for neurodegeneration and convey potential drug repurposing opportunities promoting neuroprotection. Experimental validation of the pharmacologic interventions proposed here would constitute the next stage in the drug development for the proposed targets and compounds. Further evolution of this paradigm shift viewing peripheral immunity dysregulation as a potential driver of neurodegeneration could lead to novel therapeutic approaches for the treatment of PD and AD.

Methods

Selection of gene expression datasets

Data analysis workflows broadly followed our previously published studies on human host response to various intra-cellular residing pathogens including bacteria78, viruses79 and tuberculosis66. Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (as of June 2018) was queried for human blood microarray gene expression datasets in response to Herpesviridae infection, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease. The specific search terms used were: “HSV”, “EBV”, “HHV6”, “CMV”, “Alzheimer’s Disease”, “Parkinson’s Disease”, “Homo sapiens”, and “Whole blood”. The retrieved datasets were filtered based on the following criteria: gene expression profiles from published studies which were: 1) raw data available and derived from human cells of AD/PD or single virus infected patients; 2) there was at least one control group (healthy subjects) and one diseased group and; 3) data originated from human array platforms. Additionally, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and Huntington’s Disease (HD) datasets were included to allow gene expression comparisons with unrelated neurodegenerative and non-infectious diseases and serve as controls for spurious comparisons. Table S1 summarizes all retrieved datasets along with the reasons for their inclusion or exclusion from our analyses.

Raw (intra-slide normalized) gene expression data, study design table and annotation table of each dataset were obtained from the GEO/ArrayExpress databases and processed using ArrayStudio v10.0 (OmicSoft, USA). The datasets retrieved are microarray datasets obtained from the following platforms: Illumina Human HT, Affymetrics Human Genome U133 and Affymetrics Exon Array (Table S1). Several datasets (GSE42834, GSE56153, GSE31348 and GSE36238) were further excluded due to both a noisy kernel density plot and low within group pairwise correlation (correlation cutoff 0.9, Table S1), but were included as independent datasets for validation purposes. After quality filtering, six microarray datasets (GSE636063, GSE99039, GSE81246, GSE202007, GSE458298, and GSE40396) from either whole blood or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were retained for further analysis.

Data processing and statistical analysis

Quality Control analyses were performed in all datasets selected66. Data imported was previously normalized. Intra-slide normalization was assessed by: 1) kernel density; 2) Principal Component Analysis or PCA (showing divergent samples within groups); 3) Median Absolute Deviation (MAD) score and; 4) within group pairwise correlation. Samples were considered outliers if failed at least two of these assessments. Samples irrelevant to our study design (such as samples from host response to bacteria and viruses other than HHV6 in GSE40396) were also excluded. In total, 6 samples from AD, 2 samples from PD datasets were excluded. All samples in CMV, EBV, HHV6 and T2DM datasets passed QC.

For each dataset, scale quantile inter-slide normalization (fixed target median value to 500), log2 transformation and probe differential expression analysis was performed in ArrayStudio v10.0 (OmicSoft, USA). When more than one probe mapped to a gene, the expression value of the lowest p-value was used for that gene (the “aggregate” R function was applied). Differentially expressed genes (DEG) passed the false discovery rate adjusted [FDR-adj.] p-value threshold of 0.05. The AD or PD DEG list was compared with the list of DEGs associated with CMV, EBV or HHV6 host response to identify shared gene expression signatures. The statistical significance of the overlap between AD/PD DEGs with CMV, EBV or HHV6 DEGs was assessed with a hypergeometric test (using the “phyper” R function).

Pathway enrichment analysis

Pathway enrichment analysis was performed for all DEGs from each dataset using MetaCore/MetaBase (GeneGo) v6.34 (Thomson Reuters, https://portal.genego.com/)66. The p-value for each of the 1480 human canonical pathways in MetaCore was generated using a hypergeometric test with an FDR-adj. p-value cutoff of 0.01. The Compare Experiments Workflow tool was used for comparing gene expression data across different datasets (AD/PD DEG with CMV, EBV or HHV6 DEGs) by analyzing their intersections in terms of their mappings onto MetaCore’s ontologies, including canonical pathway maps.

Genetic variants enriched in candidate gene region

Based on the shared genes across AD or PD and CMV, EBV and HHV6 DEGs, we searched the Open Targets80 validation platform to identify genetic variants proximal to these candidate gene targets associated with AD or PD. Sources of genetic associations in Open Targets include the following: the GWAS catalog, Genomics England PanelApp, the PheWAS catalog, the European Variation Archive (EVA) and Gene2Phenotype80. Variant-gene assignment considered deleterious consequences within the gene coding region, and the variant location within introns or regulatory regions. Intergenic variants assigned to the promoter region of the nearest gene were also retrieved in this search.

Gene expression validation in human microglia available datasets

To validate the expression profile of blood sample DEGs, publicly available datasets with human microglia gene expression datasets were identified in GEO database. Raw gene expression files were downloaded from GSE9907440.An initial quality check of host RNA-Seq data was performed using FastQC81. Quality filtered reads were mapped to the human reference genome GRCh38 ensembl 86 using STAR82, and quantified with featureCounts83. The data was annotated with Biomart84, and gene expression measurements were reported in log2 transcripts per million (TPM).

Drug-target prioritization

To link putative targets (DEGs) to public compounds, we obtained evidence from approved and marketed drugs that are associated to 11,538 targets from the EMBL-EBI ChEMBL database v2385. This analysis included data on drugs that have been approved for marketing by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and direct clinical evidence of interaction with the encoded DEG.

In addition, we performed drug repurposing analysis with the Connectivity Map45 (CMAP, https://www.broadinstitute.org/cmap/). For each gene expression profile to host response to CMV, EBV and HHV6, the 500 genes that ranked (based on FDR-adj. p-values) at the very top and bottom of each list were selected and compared against the gene expression profiles from the Broad CMAP compound library. Significant compounds were prioritized based on anti-correlated compound enrichment score, which represents compounds inversely matched to the disease signatures surveyed (score < 0; FDR-adj. p-value ≤ 0.05; compound specificity < 0.1). To enable result interpretation, ChEMBL data85 on target, mechanism of action, and drug indication was integrated. Compounds with unknown mechanism of action, no clinical use or antibacterial effect were excluded from our results.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

ACS is supported by the GSK Early Talent Post-doctoral Fellowship Program. We thank Lynn Marks, Lon Cardon, Allen Oliff, Min Li, Zhenhua Wu, Chun-Fang Xu and Alex Gutteridge for discussions and support. We also thank Nikolina Nakic, Vinaya Vijayan, Deepak Rajpal and Zhang Wang for computational advice.

Author Contributions

A.C.C.S. conceived the study design, performed all data analysis, and wrote the paper. H.M. conceived the study design, instructed on data analysis and contributed to manuscript writing. J.R.B. conceived the study design, instructed on data analysis and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

A.C.C.S., H.M. and J.R.B. were employees of GlaxoSmithKline at the time of this study, and H.M. and J.R.B. are company shareholders. There are no other financial or non-financial competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-45129-8.

References

- 1.Nussbaum RL, Ellis CE. Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1356–1364. doi: 10.1056/NEJM2003ra020003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masters CL, et al. Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15056. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poewe W, et al. Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17013. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmer R, Lauter H. Diagnosis, differential diagnosis and nosologic classification of the dementia syndrome. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1988;21(Suppl 1):1–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1017057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Itzhaki RF. Herpes simplex virus type 1 and Alzheimer’s disease: possible mechanisms and signposts. FASEB J. 2017;31:3216–3226. doi: 10.1096/fj.201700360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song F, Poljak A, Smythe GA, Sachdev P. Plasma biomarkers for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res Rev. 2009;61:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamza TH, et al. Common genetic variation in the HLA region is associated with late-onset sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet. 2010;42:781–785. doi: 10.1038/ng.642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van den Pol AN. Viral infections in the developing and mature brain. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:398–406. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deleidi M, Isacson O. Viral and inflammatory triggers of neurodegenerative diseases. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:121ps123. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colangelo AM, Alberghina L, Papa M. Astrogliosis as a therapeutic target for neurodegenerative diseases. Neurosci Lett. 2014;565:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henderson G, Jaber T, Carpenter D, Wechsler SL, Jones C. Identification of herpes simplex virus type 1 proteins encoded within the first 1.5 kb of the latency-associated transcript. J Neurovirol. 2009;15:439–448. doi: 10.3109/13550280903296353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porcellini E, Carbone I, Ianni M, Licastro F. Alzheimer’s disease gene signature says: beware of brain viral infections. Immun Ageing. 2010;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westman G, et al. Decreased HHV-6 IgG in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Neurol. 2017;8:40. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carbone I, et al. Herpes virus in Alzheimer’s disease: relation to progression of the disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hogestyn JM, Mock DJ, Mayer-Proschel M. Contributions of neurotropic human herpesviruses herpes simplex virus 1 and human herpesvirus 6 to neurodegenerative disease pathology. Neural Regen Res. 2018;13:211–221. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.226380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wozniak M, Bell T, Denes A, Falshaw R, Itzhaki R. Anti-HSV1 activity of brown algal polysaccharides and possible relevance to the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;74:530–540. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Chiara G, et al. Infectious agents and neurodegeneration. Mol Neurobiol. 2012;46:614–638. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8320-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sood S, et al. A novel multi-tissue RNA diagnostic of healthy ageing relates to cognitive health status. Genome Biol. 2015;16:185. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0750-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shamir R, et al. Analysis of blood-based gene expression in idiopathic Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2017;89:1676–1683. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riou, R. et al. Severe Symptomatic Primary Human Cytomegalovirus Infection despite Effective Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses. J Virol91, 10.1128/JVI.02245-16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Nikitin PA, et al. An ATM/Chk2-mediated DNA damage-responsive signaling pathway suppresses Epstein-Barr virus transformation of primary human B cells. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:510–522. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith N, et al. Induction of interferon-stimulated genes on the IL-4 response axis by Epstein-Barr virus infected human b cells; relevance to cellular transformation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu X, Yu J, Crosby SD, Storch GA. Gene expression profiles in febrile children with defined viral and bacterial infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:12792–12797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302968110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hagenbuchner J, et al. FOXO3-induced reactive oxygen species are regulated by BCL2L11 (Bim) and SESN3. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:1191–1203. doi: 10.1242/jcs.092098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson MR, et al. Systems genetics identifies Sestrin 3 as a regulator of a proconvulsant gene network in human epileptic hippocampus. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6031. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell BM, Charych E, Lee AW, Moller T. Kynurenines in CNS disease: regulation by inflammatory cytokines. Front Neurosci. 2014;8:12. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guillemin GJ, Brew BJ, Noonan CE, Takikawa O, Cullen KM. Indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase and quinolinic acid immunoreactivity in Alzheimer’s disease hippocampus. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2005;31:395–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2005.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Widner B, et al. Tryptophan degradation and immune activation in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2000;107:343–353. doi: 10.1007/s007020050029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arner ES, Holmgren A. Physiological functions of thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:6102–6109. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arodin L, et al. Alteration of thioredoxin and glutaredoxin in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;39:787–797. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Venkitaramani DV, et al. Beta-amyloid modulation of synaptic transmission and plasticity. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11832–11837. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3478-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arend WP, Malyak M, Guthridge CJ, Gabay C. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist: role in biology. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:27–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dzwonek J, Rylski M, Kaczmarek L. Matrix metalloproteinases and their endogenous inhibitors in neuronal physiology of the adult brain. FEBS Lett. 2004;567:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.03.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Healy DG, et al. Phenotype, genotype, and worldwide genetic penetrance of LRRK2-associated Parkinson’s disease: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:583–590. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70117-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.West AB, et al. Parkinson’s disease-associated mutations in leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 augment kinase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16842–16847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507360102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schapansky J, Nardozzi JD, LaVoie MJ. The complex relationships between microglia, alpha-synuclein, and LRRK2 in Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience. 2015;302:74–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaizer EC, et al. Gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from children with diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3705–3711. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pankla R, et al. Genomic transcriptional profiling identifies a candidate blood biomarker signature for the diagnosis of septicemic melioidosis. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R127. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-11-r127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee JM, et al. Dominant effects of the Huntington’s disease HTT CAG repeat length are captured in gene-expression data sets by a continuous analysis mathematical modeling strategy. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:3227–3238. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Galatro TF, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of purified human cortical microglia reveals age-associated changes. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:1162–1171. doi: 10.1038/nn.4597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nelson MR, et al. The support of human genetic evidence for approved drug indications. Nat Genet. 2015;47:856–860. doi: 10.1038/ng.3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rinne JO, et al. Increased brain histamine levels in Parkinson’s disease but not in multiple system atrophy. J Neurochem. 2002;81:954–960. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jimenez-Jimenez FJ, Alonso-Navarro H, Garcia-Martin E, Agundez JA. Thr105Ile (rs11558538) polymorphism in the histamine N-methyltransferase (HNMT) gene and risk for Parkinson disease: A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4147. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen XX, et al. The impact of GAB2 genetic variations on cerebrospinal fluid markers in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:171. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.04.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lamb J, et al. The Connectivity Map: using gene-expression signatures to connect small molecules, genes, and disease. Science. 2006;313:1929–1935. doi: 10.1126/science.1132939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zandi PP, Breitner JC, Anthony JC. Is pharmacological prevention of Alzheimer’s a realistic goal? Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2002;3:365–380. doi: 10.1517/14656566.3.4.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bettens K, Sleegers K, Van Broeckhoven C. Genetic insights in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:92–104. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kalia LV, Lang AE. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2015;386:896–912. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lodato MA, et al. Aging and neurodegeneration are associated with increased mutations in single human neurons. Science. 2018;359:555–559. doi: 10.1126/science.aao4426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perry VH, Holmes C. Microglial priming in neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:217–224. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Latta CH, Brothers HM, Wilcock DM. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease; A source of heterogeneity and target for personalized therapy. Neuroscience. 2015;302:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.09.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chahine LM, Stern MB, Chen-Plotkin A. Blood-based biomarkers for Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20(Suppl 1):S99–103. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(13)70025-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grunblatt E, et al. Gene expression as peripheral biomarkers for sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16:627–634. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liew CC, Ma J, Tang HC, Zheng R, Dempsey AA. The peripheral blood transcriptome dynamically reflects system wide biology: a potential diagnostic tool. J Lab Clin Med. 2006;147:126–132. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maes OC, et al. Transcriptional profiling of Alzheimer blood mononuclear cells by microarray. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:1795–1809. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sullivan PF, Fan C, Perou CM. Evaluating the comparability of gene expression in blood and brain. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006;141B:261–268. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang R, et al. Metabolic stress modulates Alzheimer’s beta-secretase gene transcription via SIRT1-PPARgamma-PGC-1 in neurons. Cell Metab. 2013;17:685–694. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rosenberg GA. Matrix metalloproteinases and their multiple roles in neurodegenerative diseases. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:205–216. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70016-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pei Y, Banerjee S, Jha HC, Sun Z, Robertson ES. An essential EBV latent antigen 3C binds Bcl6 for targeted degradation and cell proliferation. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006500. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Simon-Sanchez J, et al. Genome-wide association study reveals genetic risk underlying Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1308–1312. doi: 10.1038/ng.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zimprich A, et al. Mutations in LRRK2 cause autosomal-dominant parkinsonism with pleomorphic pathology. Neuron. 2004;44:601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haugarvoll K, et al. Lrrk2 R1441C parkinsonism is clinically similar to sporadic Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2008;70:1456–1460. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000304044.22253.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bae JR, Lee BD. Function and dysfunction of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2): Parkinson’s disease and beyond. BMB Rep. 2015;48:243–248. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2015.48.5.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hakimi M, et al. Parkinson’s disease-linked LRRK2 is expressed in circulating and tissue immune cells and upregulated following recognition of microbial structures. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2011;118:795–808. doi: 10.1007/s00702-011-0653-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gardet A, et al. LRRK2 is involved in the IFN-gamma response and host response to pathogens. J Immunol. 2010;185:5577–5585. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang Z, Arat S, Magid-Slav M, Brown JR. Meta-analysis of human gene expression in response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection reveals potential therapeutic targets. BMC Syst Biol. 2018;12:3. doi: 10.1186/s12918-017-0524-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu Z, et al. The kinase LRRK2 is a regulator of the transcription factor NFAT that modulates the severity of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1063–1070. doi: 10.1038/ni.2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Olson KE, Gendelman HE. Immunomodulation as a neuroprotective and therapeutic strategy for Parkinson’s disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2016;26:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xu Y, et al. Neurotransmitter receptors and cognitive dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2012;97:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ayutyanont N, et al. The Alzheimer’s prevention initiative composite cognitive test score: sample size estimates for the evaluation of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease treatments in presenilin 1 E280A mutation carriers. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75:652–660. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Longo FM, Massa SM. Neuroprotective strategies in Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroRx. 2004;1:117–127. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.1.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Group A-FR. Follow-up evaluation of cognitive function in the randomized Alzheimer’s Disease Anti-inflammatory Prevention Trial and its Follow-up Study. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:216–225 e211. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mastroeni D, et al. Laser-captured microglia in the Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s brain reveal unique regional expression profiles and suggest a potential role for hepatitis B in the Alzheimer’s brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2018;63:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lovheim H, Gilthorpe J, Adolfsson R, Nilsson LG, Elgh F. Reactivated herpes simplex infection increases the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:593–599. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.04.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lovheim H, et al. Herpes simplex infection and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: A nested case-control study. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:587–592. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.07.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lovheim H, et al. Interaction between Cytomegalovirus and Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Associated with the Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease Development. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;61:939–945. doi: 10.3233/JAD-161305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Readhead B, et al. Multiscale Analysis of Independent Alzheimer’s Cohorts Finds Disruption of Molecular, Genetic, and Clinical Networks by Human Herpesvirus. Neuron. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Smith SB, Magid-Slav M, Brown JR. Host response to respiratory bacterial pathogens as identified by integrated analysis of human gene expression data. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Smith SB, Dampier W, Tozeren A, Brown JR, Magid-Slav M. Identification of common biological pathways and drug targets across multiple respiratory viruses based on human host gene expression analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33174. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Koscielny G, et al. Open Targets: a platform for therapeutic target identification and validation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D985–D994. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. Available online athttps://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (2010).

- 82.Dobin A, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:923–930. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Durinck S, Spellman PT, Birney E, Huber W. Mapping identifiers for the integration of genomic datasets with the R/Bioconductor package biomaRt. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1184–1191. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Davies M, et al. ChEMBL web services: streamlining access to drug discovery data and utilities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W612–620. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kumar A, Singh A. & Ekavali. A review on Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology and its management: an update. Pharmacol Rep. 2015;67:195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Blass JP, Cyrus PA, Bieber F, Gulanski B. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study to evaluate the safety and tolerability of metrifonate in patients with probable Alzheimer disease. The Metrifonate Study Group. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2000;14:39–45. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200001000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Heckman PR, Wouters C, Prickaerts J. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors as a target for cognition enhancement in aging and Alzheimer’s disease: a translational overview. Curr Pharm Des. 2015;21:317–331. doi: 10.2174/1381612820666140826114601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lan YL, Zhao J, Li S. Update on the neuroprotective effect of estrogen receptor alpha against Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;43:1137–1148. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.