Abstract

Parental stress has been shown associated with children’s eating behaviors. The stress-buffering hypothesis suggests that social resources, i.e., resources accessed via one’s social networks, may prevent or attenuate the impact of stress on health. Prior research on the stress-buffering hypothesis has found evidence for the protective effects of social support (emotional, instrumental, or informational resources available in a person’s life); less is known about social capital (resources available through one’s social networks) as a stress buffer. Further, these studies have often examined the association between a person’s direct access to social resources and their health; less research has examined whether the benefits of social resources may extend two degrees from parents to their children. Using data from a community-based birth cohort of mother-child dyads, this study examined whether mother’s social capital moderated the association between maternal stress and children’s emotional overeating (EO). Mothers completed health questionnaires on an annual basis and a one-time social network questionnaire in 2011-2012. EO was measured using the Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire. Maternal stress was measured using the 18-item Parental Stress Scale. Social capital was measured using a position generator and based on the number of occupations to which a mother had access. Poisson regression analysis was used. Results showed that mother’s social capital moderated the positive association between greater maternal stress and children’s EO, such that maternal stress was associated with children’s EO in only those mothers with low social capital. This study suggests that social capital may disrupt the transmission of maternal stress from parent to child, thereby playing a potential role in the production and reproduction of health inequalities.

Keywords: social capital, stress, children, emotional overeating

INTRODUCTION

The stress-buffering hypothesis suggests that social resources may prevent or attenuate the impact of stress on health (Cohen and Wills, 1985). Studies have shown that individuals with access to more social resources, particularly social support, have more favorable health outcomes compared to those with access to fewer resources (Baek et al., 2014; Bowen et al., 2014). Research on the stress-buffering hypothesis has focused on the role that social resources play in buffering the negative health consequences of stress for those with direct access to social resources (i.e., first-degree contacts). Little research has examined whether the protective benefits that social resources offer against stress extend to second-degree contacts, e.g., from parents to their children. While studies have shown that children exposed to parental stress are at greater risk of adverse health outcomes (Toepfer et al., 2017), less attention has been given to whether a parent’s social resources might attenuate the effects of stress on children’s health.

With certain exceptions (Song and Lin, 2009), research on the stress-buffering role of social resources has focused on social support. Social support refers to the emotional, instrumental, or informational assistance available in a person’s life, with support typically provided by a person’s stronger social ties, e.g., family or close friends (Thoits, 2011). Less is known about the role of social capital in attenuating the impact of stress on health. Social capital refers to the resources embedded in individuals’ and groups’ social networks (Bourdieu, 1986; Song and Lin, 2009). Unlike social support, social capital tends to emerge from a person’s weaker social ties and captures the structural positions accessed within personal networks (Song and Lin, 2009; Moore, Teixeira, and Stewart, 2016). Weaker ties might be between an individual and their coworkers or neighbors, whereas stronger ties may between family and close friends. Weak ties can act as important bridges between social networks or diverse members within a network (Granovetter, 1973). While social support may buffer stress via the interpersonal provisioning of specific types of resources, (e.g., emotional support), social capital may buffer stress by providing access to diverse resources and fostering greater social cohesion through weak ties (Granovetter, 1973). Because social support and social capital tend to represent dissimilar types of social resources and emerge from different social ties, they may also provide unique social and psychosocial protections against stress (Lin, 2001). Social capital and social support should thus be measured and studied as independent constructs, representing potentially different mechanisms influencing health (Song and Lin, 2009). The following study expands previous research on the stress-buffering hypothesis by examining whether mother’s social capital moderates the association between maternal stress and children’s eating behaviors. In so doing, we aim to understand the potential importance of mother’s social capital in the intergenerational transmission of stress and health.

Emotional overeating

Appetitive traits such as emotional overeating provide insight into how dimensions of eating behavior interact with other behavioral, social, and environmental factors to influence risk of diet-related diseases, including obesity. Emotional overeating refers to eating in the absence of internal hunger cues, and it occurs in response to emotions such as worry, annoyance, boredom, and anxiety (Santos et al., 2011). Research suggests that emotional overeating may be a coping strategy among children in high-stress households (Puder and Munsch, 2010); children may overeat to manage external stress and anxiety, and to cope with negative emotions (Goossens et al., 2009).

Emotional overeating has been associated with a heightened risk of obesity among children, suggesting that emotional overeating may lie on the causal pathway linking stress and obesity (Webber et al., 2009). For example, children’s emotional overeating has been associated with the consumption of more energy dense, high-fat foods (Nguyen-Michel et al. 2007), weight gain, and obesity risk (Croker et al., 2011; Webber et al., 2009). In one study, children who exhibited emotional overeating were at more than twice the risk of being overweight as their peers (Eloranta et al., 2012). Importantly, the risk of emotional overeating may increase over time, as appetitive traits related to satiety decrease and food responsiveness increase with age (Ashcroft et al., 2007). Previous studies have examined how individual behaviors, such as emotional overeating, influence children’s risk of obesity.

Maternal stress and children’s health

Parental stress refers to stress that occurs in the parent-child relationship, due in particular to the everyday strains and conflicts that come with occupying a parental role. These more chronic strains include such factors as balancing responsibilities, financial burden, and concern among parents that they are doing enough for their children (Berry and Jones, 1995). Our study focuses specifically on the stress to which women might be exposed in their role as a child’s mother, hereafter referred to as maternal stress. While the maternal role can be rewarding, maternal stress can affect the household environment and behaviors that occur within the family (Umberson et al., 2010). Children’s exposure to stress early in life, including stress from mothers, has been associated with their health behaviors and conditions, including eating behaviors and risk of obesity (Garasky et al., 2009). For example, Parks and colleagues (2012) have shown that the higher the number of household stressors to which a child is exposed, the more their consumption of fast food. Mothers under stress may seek to save time or reduce the demands of meal preparation as a response to everyday time demands and stressors (Parks et al., 2012). These decisions might spill over to children’s health and behaviors through the food that children ultimately consume and the eating habits and tastes that they develop.

The mother-child relationship has been recognized as central to the intergenerational transmission of stress (Toepfer et al., 2017). Children exposed to higher levels of maternal stress have been shown to have higher levels of stress in adulthood (Liu and Umberson, 2015). They may also be more sensitive to other types of social stressors over the life course, thereby leading to cumulative health disadvantages in later life (Liu and Umberson, 2015; Miller et al., 2011). Research has suggested that the intergenerational transmission of stress may occur along various pathways, including through the epigenetic alteration of oxytocin pathways (Toepfer et al., 2017; Meaney, 2001) or the development of pro-inflammatory tendencies in cells of the immune system. These alterations can become heightened over the life course through continued exposure to stress, unhealthy behaviors, and hormonal dysregulation, contributing to the premature appearance of chronic disease (Miller et al., 2011). Understanding whether a mother’s social resources buffer the short- and long-term effects of maternal stress on children’s health may provide insight into how programs and policies can disrupt those transmission routes.

The stress-buffering hypothesis

The stress-process model offers a general conceptual framework for guiding researchers in their thinking about the causes and consequences of stress for health (Pearlin, 1999). Three important assumptions underlie the stress-process model (Pearlin, 1999). First, the model suggests that the health consequences of stress should be considered as a process that takes place over time and within particular social environments, and not simply as the immediate outcome of a discrete stressful event. Second, the stress process concerns the normative features of everyday life and those difficult, chronic social stressors that individuals and households face. Finally, social research on stress examines the origins of stress and not its physiological consequences (Pearlin, 1999). Not only are stress effects contingent on the type or severity of the social stressors experienced but also on the types and amount of resources (e.g., social, coping, or self-concept) that individuals or groups possess.

The stress-buffering hypothesis posits that a person’s social resources may prevent or attenuate the effects of stress on health. In situations of high stress, social resources may act as a buffer against various diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and depression (Baek et al., 2014; Ikeda et al., 2008). Social resources may intervene in the pathway from stress to disease by either attenuating the stress appraisal response or reducing the stress reaction (Cohen and Wills, 1985). In this first possibility – attenuating or preventing the stress appraisal response – social resources encourage a less threatening interpretation of the stressful event. In the second, social resources might provide individuals with key resources and supports that help to reduce the body’s adverse reaction to stress. Despite the rich history of research in this field, gaps remain in our knowledge of the role and impact of social resources in the stress-buffering process. For example, most research on stress buffering has focused on social support as providing stress buffering resources, with little attention given to the potential importance of social capital. While both constructs are meant to provide insight into the content and structure of social relationships (Saegert and Carpiano, 2017), there are important distinctions to be drawn.

Social capital and social support

Social capital and social support are two key constructs in the study of social networks and health. Social capital is often defined as the resources to which individuals or groups have access through their social networks. Research on social capital and health has often emphasized the importance of weak ties (e.g., friends and acquaintances) and network diversity for a range of health behaviors and conditions (Berkman et al., 2000; Moore et al., 2016). Weak ties may act as bridges between network actors or network clusters themselves. Through their bridging function, weak ties connect more isolated groups or communities, create a greater sense of social integration, and can be important for diffusing diverse information within and between networks (Granovetter, 1973; Fujimoto et al., 2015). Researchers have relied on a number of different measurement instruments to capture a person’s social capital, including position, name, and resource generators (Marsden, 1987). Position generators, for example, capture social capital by assessing a person’s access to occupations lying along a broad socioeconomic spectrum (Lin and Dumin, 1986). Having access to different occupations is meant to be indicative of the diversity (the number of occupations), reach (the most prestigious occupation), and range (the difference between the lowest- and highest-prestige occupations) of socially-valued resources to which one has access (Lin, 2001). Despite the breadth of research on social capital, few studies have examined whether social capital might buffer the impact of stress on health. When undertaken, this research often focuses on the role of neighborhood social capital (measured as area-level trust) in moderating the association between neighborhood stressors and health outcomes (Carpiano and Kimbro, 2012).

Research on social support draws from the fields of medical sociology and social and community psychology, where social support is viewed as interpersonal resources (e.g., emotional, instrumental, and information) that individuals might access from a range of sources (e.g., family, friends, acquaintances) (Saegert and Carpiano, 2017; Thoits, 2011; Turner et al., 2014; Uchino, 2009). For example, measures of emotional support typically ask individuals whether they have people in their lives who care for or encourage them, whereas measures of instrumental support often capture whether tangible resources or functional aid, such as providing transportation, are available to individuals (Gottlieb and Bergen, 2010; Cyranowski et al., 2013). Despite the fact that studies of social support might examine different sources and types of support, most research has investigated emotional support and the importance of strong ties (i.e., family, close friends) in the provisioning of such resources. As a result, social support research has evolved with greater focus on the content rather than the structure of social relationships (Saegert and Carpiano, 2017). This focus is reflected in how social support is typically measured. Scales measuring social support aim to capture the emotional, instrumental, and informational assistance that individuals either perceive as available or receive in a particular context (Thoits, 2011). Perceived support refers to a person’s perceptions of support or support availability, with these perceptions likely rooted in early childhood experiences and formed over time from daily social exchanges (Berkman et al., 2000; Thoits, 2011). Received support, on the other hand, refers to support resources sought and provided in response to stressful circumstances (Uchino, 2009). As stress buffers, perceived and received support are seen to be most effective when the type of support matches the challenges experienced. Perceived support may provide greater protections against the adverse health effects of stress in the appraisal process, whereas received support is more likely to be sought and received in response to a particular situation or event (Uchino, 2009).

Most research on the stress-buffering hypothesis has examined whether social resources buffer the adverse impact of stress on the health of those with direct access to those resources, i.e., first-degree contacts, and not on whether social resources buffer the impact of stress on second-degree contacts. Through their social connections, parents have access to social resources that may benefit or buffer the adverse effects of stress on their children’s health and development. For example, Nagy et al. (2016) have shown higher parental social capital associated with fewer sleep disturbances in children. Coleman (1988) found positive associations between familial social capital and children’s education, with higher social capital associated with a lower high school dropout rate. Yet, little research has examined whether a mother’s social capital moderates the association between maternal stress and children’s health. If maternal social capital buffers against maternal stress, health programs and policies might leverage maternal social resources as a means of interrupting the intergenerational transmission of stress. Our study aims to examine whether mothers’ social resources buffer the association between maternal stress and children’s emotional overeating and compare the stress-buffering role of social capital with that of social support. By examining the importance of social capital in the pathway from maternal stress to children’s health, our study aims to contribute to a greater understanding of the role of social capital in the reproduction of health inequalities across generations.

METHODS

Sample

Data came from the Maternal Adversity Vulnerability and Neurodevelopment (MAVAN) cohort. MAVAN was established in 2003 to examine prospectively fetal and child development as a function of mother-child interactions and the environment in which the child is reared (O’Donnell et al., 2014). MAVAN was a community-based Canadian birth cohort, recruited between the years 2003-2009 and consisting primarily of Caucasian women from Montreal, Quebec and Hamilton, Ontario and their children. To be eligible, women had to be aged 18 years or older at time of delivery, be expected to have a singleton birth, and be fluent in English or French. Women were excluded from the study if they had a severe chronic maternal illness, faced serious complications during their pregnancy or delivery, or if their child was born prematurely or with very low birth weight. Using a combination of methods, including surveys and laboratory experiments, MAVAN mothers and their children have been assessed along a range of health, social, behavioral, and developmental conditions at 6, 12, 18, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 months after delivery. The original cohort had a sample size of 551 mother-child dyads residing in Montreal and Hamilton, Canada. Compared to the general adult population, MAVAN mothers tended to have relatively lower income but higher education levels. By 2012, attrition from MAVAN had led to a sample of 287 dyads, with 170 of those in Montreal. Previous analyses examining the impact of attrition on the composition of the MAVAN cohort showed no differences in maternal age, income, and maternal education between the original cohort and later cohort members (Silveira et al., 2014).

The social capital/social networks module was administered to MAVAN mothers based in Montreal between November 2011 and February 2012 (n=120). For this study, we restricted our study to those mother-child dyads in which the child was six years old (n=102) and who had completed their 72-months assessment. This reduced any potential confounding due to developmental differences between four- or five-year-old and six-year-old children, and any differences in maternal stress between mothers with six-year-olds and those with younger children. After excluding observations missing information on children’s emotional overeating (n=14) or other study variables (n=4), the final sample size was 84 unique Montreal-based mother-child dyads. ANOVA and chi-square tests comparing those observations dropped from this analysis to those included showed no differences between the two groups on this study’s independent variables. Ethical approval for MAVAN was obtained from the Douglas Mental Health Hospital at McGill University and St. Joseph’s Hospital.

Measures

Outcome:

For this study, children’s emotional overeating was based on a four-item subscale of the Children’s Eating Behavior Questionnaire (CEBQ) that parents completed on their children at the 72-months assessment. The CEBQ consists of 35-items that measure eight dimensions of children’s eating, including food responsiveness, enjoyment of food, and slowness in eating (Wardle et al., 2001). The CEBQ has been used to measure eating behaviors among children as young as two years of age (Wardle et al., 2001), and more recent studies have validated the survey among preschool and primary school-aged children (Carnell and Wardle, 2007; Domoff et al., 2015). Parents completed the CEBQ The emotional overeating subscale consisted of the following four items: (1) “My child eats more when worried”; (2) “My child eats more when annoyed”; (3) My child eats more when anxious”; and (4) “My child eats more when she/he has nothing else to do.” Parents rated their child on each of these items using a 5-point scale (“never”, “rarely”, “sometimes”, “often” and “always”) (scored 1-5). Children’s emotional overeating scores were the sum of these four items, with scores ranging between 4-20. Scores were calculated for participants who responded to each of the four items. The Cronbach’s alpha for the emotional overeating scale was 0.79.

Exposure:

Maternal stress was measured using the 18-item Parental Stress Scale (Berry and Jones, 1995). Mothers were asked to respond on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5)) to items such as “I sometimes worry whether I am doing enough for my child(ren)” and “Having children leaves little time and flexibility in my life.” (Berry and Jones, 1995). Eight items were reverse coded so that greater values represented higher levels of maternal stress. Participants’ responses were averaged across the 18 items, with overall scores possibly ranging from 1-5. Maternal stress represents positive and negative aspects of parenthood, and has been shown related to a variety of emotional and role satisfaction variables (e.g., guilt, marital and job satisfaction) (Berry and Jones, 1995). The MAVAN maternal stress scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85 for the 72-months administration.

Moderators:

Social capital was measured using a position generator instrument (Lin, 2001). The position generator was adapted from previous Montreal health studies and consisted of a list of ten different occupations (e.g., physician, teacher, receptionist) with a range of prestige scores (Moore et al., 2011). Mothers were asked to indicate whether they knew someone on a first name basis in each of the ten listed occupations. If a participant indicated that they knew one or more people with a particular occupation, they were asked to think of the person who was closest to them in the occupation and indicate if they were a relative, friend or acquaintance. Social capital was based on the number of different occupations (0-10) to which a participant had access on the position generator. Network diversity has been shown correlated with adult and children’s health behaviors and conditions (Moore et al., 2011; Carpiano and Hystad, 2011; Nagy et al., 2016).

Social support was based on the different types of support that mothers reported receiving over the past two weeks. Five items on received support were assessed: (1) support with something like furniture, money, clothes, or food (instrumental support); (2) with babysitting children, running errands or cleaning the house (instrumental support); (3) with information, input, or guidance in a particular situation, for them or another member of their family (information support); (4) with having someone to talk to about something personal or intimate in nature (emotional support); (5) with having someone give them positive feedback or approval or having been told that they made the right decision (appraisal support). Social support scores represented a count of the number of different items of support that a participant reported receiving, with scores thus ranging from 0-5.

Confounders:

Our analyses adjusted for maternal age, maternal educational attainment, household income, the child’s sex, partner/marital status, and concerns that the parent might have about the child’s weight. Since all the children in this study and analysis had recently completed their 72-months assessment, we did not control for children’s age. Maternal educational attainment included four categories: (1) high school degree or less, (2) some college, (3) college degree completed, (4) university or higher professional degree. For annual household income, respondents selected from one of 17 income categories. Income was kept as a continuous variable ranging from 1-17 in the analyses. However, for the descriptive statistics, we collapsed the 17 categories into five categories. Maternal age and educational attainment were also treated as continuous variables. Sensitivity tests were conducted to assess whether treating age, income, or educational attainment as categorical or indicator variables rather than continuous variables provided a better fitting model. In all cases, the continuous form of the variable provided the better fit. The child’s sex was based on the mother’s self-report, which was confirmed through genotyping of the sex chromosomes. To disentangle general maternal stress from specific worries that may be due to concerns about a child’s diet and weight, we included in our analyses a measure for a mother’s concerns about their child’s weight. Three items from the Child Feeding Questionnaire were used to construct this measure. These items were: 1) “How concerned are you about your child eating too much when you are not around him/her?”; (2) “How concerned are you about your child having to diet to maintain a desirable weight?”; (3) “How concerned are you about your child becoming overweight?” Parents responded using a 5- point Likert scale (“unconcerned,” “slightly concerned,” “neutral,” “slightly concerned,” “concerned”). The Cronbach’s alpha for the weight concerns subscale was 0.82.

Data Analysis

Emotional overeating was positively skewed. Poisson regression was determined as an appropriate approach, with tests for overdispersion negative. Three different modeling steps were undertaken. First, we ran a series of bivariate models (Model 1) to examine the association between emotional overeating and study variables. Second, we tested the stress-buffering hypothesis by assessing whether social capital (Model 2a) and social support (Model 2b) moderated the association between maternal stress and children’s emotional overeating. Finally, we assessed whether social capital or social support moderated the association between maternal stress and children’s emotional overeating while adjusting for study variables. Model 3 presents this full model, along with any interaction variables shown to be significant in Models 2a and 2b. To better assess effect modification, mothers were then assigned into one of nine groups based on the cross classification of the sample into tertiles of stress and social capital. Post-estimation tests were conducted to assess the nature of effect modification. Ancillary sensitivity tests examined whether the social capital relationship role (i.e., relative, friend, or acquaintance tie) or social support type (i.e., instrumental, emotional, informational, or appraisal) mattered for study results. Analyses report the robust standard errors for the parameter estimates to account for any mild violation of underlying assumptions (Cameron and Trivedi, 2009). Stata (version 14) was used for analyses.

RESULTS

Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics of our study sample. In general, the mothers in our analytical sample of 84 mother-child dyads tended to be well educated with 52% having a university degree and 30% living in a household earning over $100,000 Canadian dollars annually. On a scale from 4-20, the mean emotional overeating score was 6.95 (SD=2.93). About a third of respondents (31%) reported the lowest score possible on the emotional overeating scale. On a scale from 1-5, mothers averaged 1.68 on the Parental Stress Scale (median=1.61). Mothers reported receiving on average 2.61 different forms of social support within the previous two weeks. Mothers reported on average 5.5 ties, with roughly similar percentage of ties to relatives, friends and acquaintances. Almost 91% of mothers reported receiving some type of instrumental support and 53.6% emotional support. Social capital and received social support were not correlated (r=0.11), nor was social capital correlated with any specific type of social support.

Table 1:

Descriptive Statistics, Maternal Adversity, Vulnerability, and Neurodevelopment cohort at 72 months (MAVAN), n=84

| Variables | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Emotional Overeating | 6.95 (2.93) |

| Parental Stress | 1.68 (0.46) |

| Social capital | 5.50 (2.04) |

| Source of social capital | |

| Relative, % total | 34.1 |

| Friend, % total | 31.7 |

| Acquaintance, % total | 34.2 |

| Social Support | 2.58 (1.36) |

| Type of social support received | |

| Instrumental, % | 90.5 |

| Emotional. % | 53.6 |

| Informational, % | 52.4 |

| Appraisal, % | 61.9 |

| Mother’s Age | 35.64 (4.56) |

| Weight Concerns | 1.53 (0.99) |

| Educational attainment (1-4 levels) | 3.29 (0.93) |

| High school degree or less, % | 8.33 |

| Some college, % | 7.14 |

| Completed college or some university, % | 32.14 |

| University degree, % | 52.38 |

| Annual Household Income (1-17 levels) | 13.77 (3.78) |

| Less than $40,000, % | 21.42 |

| $40,000 - $59,999, % | 21.42 |

| $60,000 - $79,999, % | 15.48 |

| $80,000 - $99,999, % | 11.9 |

| More than $100,000, % | 29.76 |

| Child’s gender is Male, % | 44.0 |

| Mothers with spouse or partner, % | 86.9 |

Table 2 provides detailed information on the social capital of the Montreal-based MAVAN mothers. From the list of ten occupations, MAVAN mothers knew, on average, individuals in 5.5 occupations. Almost 80% of the respondents knew someone who was a nurse; whereas only 23% knew a cab driver. Information on the role relationships composing participants’ ties to specific occupations showed relative ties (54.1%) to be most common among teachers; friend ties most common among nurses (44.8%); and, acquaintance ties most common among taxi drivers (73.9%).

Table 2:

Descriptive Statistics on Occupations listed in the MAVAN Position Generator (by order of appearance on questionnaire), n=84.

| Occupation | % With Access |

% Relative |

% Friend |

% Acquaintance |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Physician | 57.1 | 33.4 | 33.3 | 33.3 |

| 2 | Nurse | 79.8 | 34.3 | 44.8 | 20.9 |

| 3 | Teacher | 72.6 | 54.1 | 27.9 | 18.0 |

| 4 | Accountant | 72.6 | 29.5 | 36.1 | 34.4 |

| 5 | Musician or Artist | 67.9 | 40.4 | 33.3 | 26.3 |

| 6 | Welder | 31.0 | 38.5 | 26.9 | 34.6 |

| 7 | Carpenter | 50.0 | 48.8 | 12.2 | 39.0 |

| 8 | Taxi cab driver | 22.6 | 10.3 | 15.8 | 73.9 |

| 9 | Receptionist | 51.2 | 9.3 | 37.2 | 53.5 |

| 10 | Janitor | 45.2 | 20.9 | 13.2 | 65.9 |

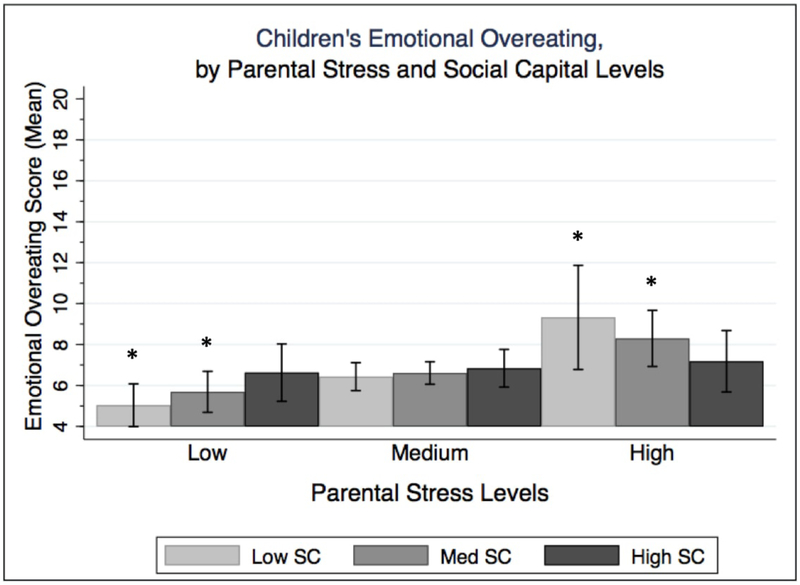

Table 3 shows the results from the Poisson regression models examining the association between emotional overeating and study variables. The bivariate analyses showed that maternal stress (IRR=1.33, 95% CI=1.12, 1.59) and weight concerns (IRR=1.15, 95% CI=1.06, 1.25) were associated with emotional overeating in children. With every unit increase in a average maternal stress score or their concerns about their child’s weight, children’s risk of emotional overeating were 33% and 15% higher respectively. Neither social capital nor social support were directly associated with emotional overeating. Models 2a and 2b both supported the stress-buffering hypothesis of social resources on emotional overeating. Social capital and support both moderated the association between maternal stress and emotional overeating. Yet, after adjusting for confounding variables, social support was no longer an effect modifier. Social capital did however moderate the association between maternal stress and emotional overeating in the adjusted model. Figure 1 shows the average emotional overeating score for children’s emotional overeating at low, medium, and high tertiles of maternal stress and social capital. Post-estimation contrast tests showed the risk of children’s emotional overeating to be 52% higher for children of mothers with high stress and low-medium social capital, compared to those mothers with low stress and low-medium social capital (IRR=1.52, 95% CI = 1.23, 1.88). Children of mothers with high stress and high social capital did not have a higher rate of emotional overeating than those of mothers with low stress. In ancillary tests, we examined whether the role relationship of participants’ network ties operated differently as effect modifiers. In fully-adjusted models, the product term of the moderation tests showed acquaintance ties (IRR=0.89; 95% CI=0.81, 0.98) to buffer the association between parental stress and children’s emotional overeating, but not friend (IRR=0.91; 95% CI=0.81, 1.04) or relative ties (IRR=1.03; 95% CI=0.93, 1.13).

Table 3:

Incidence rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals from bivariate and multivariable Poisson regression of emotional overeating on study variables, Montreal MAVAN cohort at 72 months, n=84.

| Variables | Model 1 (Bivariate) |

Model 2 (Stress-buffering) |

Model 3 (Final) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | 2b | |||

|

Maternal Parental Stress |

1.33** (1.12, 1.59) |

2.33**

(1.41, 3.86) |

1.72***

(1.31, 2.27) |

2.36**

(1.34, 4.16) |

| Social Capital | 1.00 (0.95, 1.05) |

1.19*

(1.01, 1.40) |

1.23*

(1.04, 1.46) |

|

|

Social Capital

*

Parental Stress |

0.90*

(0.82, 1.00) |

0.89*

(0.79, 0.99) |

||

| Social Support | 1.05 (0.98, 1.11) |

1.24*

(1.05, 1.46) |

1.04 (0.96, 1.10) |

|

|

Social Support

*

Parental Stress |

0.90*

(0.83, 0.99) |

|||

| Weight Concerns | 1.15**

(1.06, 1.25) |

1.19***

(1.12, 1.27) |

||

|

Mother’s Education |

0.91 (0.82, 1.00) |

0.95 (0.85, 1.05) |

||

| Mother’s Income | 0.98 0.95, 1.00) |

1.00 (0.97, 1.03) |

||

| Mother’s Age | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) |

1.00 (0.98, 1.02) |

||

|

With Spouse or Partner |

0.87 (0.70, 1.24) |

1.07 (0.82, 1.39) |

||

| Child’s Gender | 0.97 (0.81, 1.17) |

0.94 (0.80, 1.09) |

||

|

Constant (Intercept) |

1.67 (0.70, 3.99) |

2.46 (1.47, 4.12) |

1.32 (0.33, 5.33) |

|

|

Wald’s Chi- Square |

22.68*** | 18 47*** | 67.96*** | |

|

Pearson Goodness of Fit Chi-Square |

90.88 | 90.34 | 66.95 | |

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001. (Models 2 and 3 adjust for all variables shown, with the exception of the interaction between social support and maternal parental strss in Model 3.)

Figure 1.

Children’s emotional overeating, by parental stress and social capital levels.

DISCUSSION

The present study extends prior research on the stress-buffering hypothesis in numerous ways. First, the study highlighted the strength of the positive association between maternal stress and children’s emotional overeating, showing stress associated with children’s emotional overeating even at the low levels of stress and emotional overeating in our sample. As such, modifiable factors that attenuate the association between maternal stress and emotional overeating might provide significant benefits to children’s eating behaviors. Second, we showed that mothers’ social capital moderated the association between maternal stress and emotional overeating. Children’s risk of emotional overeating was greatest among mothers with high maternal stress and low and medium levels of social capital. Second, we compared the stress-buffering role of social capital and social support in a sample of mother-child dyads, showing that social capital buffered stress after adjusting for confounders, while social support did not. Our findings support the idea that social capital and social support represent distinct constructs, which perform different stress-buffering functions in the relationship between maternal stress and health (Song and Lin, 2009). Finally, we situated our analysis in an intergenerational context to highlight the role of maternal social capital in possibly disrupting the transmission of the negative effects of stress from parent to child.

Stress-buffering role of social capital

Previous research on maternal social capital and children’s health has shown higher parental social capital directly associated with better children’s health outcomes (Harpham et al., 2006; Nagy, et al., 2016; Story and Carpiano, 2017). In this study, mothers’ social capital, measured by network diversity, was shown to moderate the positive association between children’s emotional overeating and maternal stress. Most research on the stress-buffering hypothesis has focused on social support and not given attention to health outcomes among secondary, or second-degree, contacts (Bowen et al., 2014; Roth et al., 2018), unless those studies focus on caregiving to older adults (Reczek and Zhang, 2016). This study extended previous research on the stress-buffering hypothesis by examining whether the benefits that come with parents having higher social capital extended to their children.

Our study suggests that social resources might operate to reduce the adverse impact of stress on first-degree and second-degree contacts. Among first-degree contacts, the stressbuffering model posits that social resources play a protective role at different points in the causal pathway from stress to health. Social resources might attenuate or prevent a person’s appraisal of or their affective or physiological reaction to stress (Thoits, 2011). Among those mothers already reporting high maternal stress, having high social capital might mainly operated on the stress reaction process. Mothers with greater network diversity may perceive and have access to a diverse range of information, opportunities, and other resources. They also may be more likely to encounter others who can empathize with their circumstances and provide support (Thoits, 2011). This may heighten a mother’s perceived capacity to manage or cope with various stressors, reduce a parent’s affective or emotional response to stressful events, or prevent maladaptive behaviors from developing among parents.

The rates of emotional overeating were shown to be the highest in those children whose mothers reported high stress levels and low to medium social capital. Our findings suggest that high social capital acted to buffer or lessen the association between maternal stress and children’s emotional overeating only at the highest levels of stress. This finding may point to threshold effects in which social capital may exhibit nonlinear relationships with health (Gannon et al., 2014; Jay and Andersen, 2018). Further research on the particular contexts in which social capital may act to buffer the impact of stress on health conditions and behaviors is warranted, but our research highlights the importance of second-degree (mother-to-child) relationships by which the benefits of social capital may flow among individiduals. For children, or second-degree contacts, we would suggest that mothers’ social capital might buffer the effects of stress on children’s health through various mechanisms, including stress exposure, resource access, or network development mechanisms. First, research has shown the harmful effects of parental stress on children’s health and coping behaviors (Mackler et al., 2015). Stress-inducing conditions within the household have been shown to lead to maladaptive behaviors in children, (Bowers and Yehuda, 2016), and maternal stress in particular may be a salient mediator of these adverse child health outcomes (Yehuda et al., 2008). Maternal stress may have direct impacts on children’s stress reactions (e.g., emotional overeating). By reducing stress reactivity among parents, social capital would prevent or lessen a child’s exposure to stress. Second, mothers’ social capital might improve children’s health by providing children access to important instrumental resources, such as health, childcare, or better educational opportunities (Harpham et al., 2011; Nagy et al., 2016). Children whose parents have access to such resources may be better positioned to benefit from such resources themselves. Third, mothers with higher social capital may have more social connections with other parents, thereby providing greater opportunities for their children to interact with or have play dates with other kids. Such a pathway would serve to foster the child’s own social networks and resources.

Comparing social capital and social support

Our study compared the role of maternal social capital and social support in buffering the impact of maternal stress on children’s emotional overeating. While both social capital and social support moderated the association between maternal stress on children’s emotional overeating in the bivariate analyses, only maternal social capital remained significant after adjusting for confounding characteristics. This finding supports previous studies that have shown social capital and social support to be distinct constructs (Song and Lin, 2009), capturing different dimensions of personal social resources. Although Song and Lin (2009) showed a greater role for social support than social capital, their study did not examine dyadic relations between maternal stress and a child’s outcomes. Differences in the network resources (e.g., type of or quality/quantity of resources) captured by social capital and social support might partially explain why social capital was found to be more of buffer against children’s emotional overeating than social support. For example, researchers have shown social capital to emerge primarily from a person’s weaker social ties (Lin, 1999). In our sample, mothers tended to access the lower prestige occupations through acquaintances, suggesting the importance of weak ties in having more extensive networks. These weak ties play an important role in a person’s connectivity through their ability to act as bridges between networks or individual actors within a network (Granovetter, 1973). Distressed individuals with more extensive secondary group networks, composed of weak ties, would have an increased probability of encountering other individuals who can empathize with their circumstances and provide support (Thoits, 2011).

Research on social support typically examines the functions that social support may serve for individuals, focusing mainly on emotional, instrumental, and informational support (Saegert and Carpiano, 2017). MAVAN mothers reported receiving on average 2.61 out of five types of social support. While received support may come from different sources, research suggests that social support tends to emerge from a person’s strong ties and offers important protections against disease and illness (Uchino, 2006). As a stress buffer, received social support might provide a range of important support resources, including active coping assistance, expressive support, or key informational resources (Thoits, 2011). The stress-buffering benefits that received social support offers are often contingent on the particular stressors experienced (Pearlin, 1999). Problem-focused support, for example, may be beneficial for relatively manageable stressors (Uchino, 2009). While received social support acted as a moderator in the bivariate analyses, it did not remain a moderator after adjusting for confounders. Further research on the different role that social capital and social support resources may play in buffering the effects of stress on health is needed, but our findings suggest that social capital may offer protective resources in reducing the association between maternal stress and children’s eating behaviors.

Maternal social capital and the intergenerational transmission of stress

Prior research has shown that a child’s repeated exposure to stress can have cumulative and compounding effects on their health over the life course (Gustafsson et al., 2014). Exposure to early life stress, particularly maternal stress, may lead to maladaptive behaviors and poor health in children (Bowers and Yehuda, 2016; Yehuda et al., 2008). Maternal stress can also lead to stress reactivity in children via epigenetic, biological and behavioral pathways (Meaney 2001), thereby transmitting stress from generation to generation. Research has shown chronic stress related to food intake. Our study is innovative in showing that a mother’s social resources may affect the way maternal stress affects children’s eating behavior, potentially interrupting the transmission of stress reactivity from mother to child. Yet having or not having social capital is not a function of the individual decisions of mothers or parents to ‘network’ or be more socially active. Research has shown social capital to be unequally distributed in society, with social resources often distributed along socioeconomic lines (Lin 1999). Occupying an advantaged or disadvantaged social position, such as having higher income or educational attainment, can lead to differential access to social capital (Beaudoin, 2009; Lin, 2001; Mithen et al., 2015). The health benefits that may come with social capital can also fall unevenly among groups. Social capital inequalities in health refer to systematic differences in health that arise from the differential availability or accessibility of network resources (Moore et al., 2013). In our study, inequalities in maternal social capital also represent systematic differences in children’s access to stress-buffering resources. Children whose parents had greater social capital accessible to them were better protected from the detrimental health effects of maternal stress than those children who had parents with lesser social capital. As such, social capital might be seen as one mechanism by which health inequalities are reproduced. Nevertheless, further research is needed to identify the cumulative advantages or disadvantages that social capital may bring to individuals, families, and groups over time.

Limitations

There were a number of limitations to the study. First, the MAVAN cohort of women and children in Montreal is a community-based sample of limited size. Despite the drawbacks that a small, non-random sample may represent, the sample of mother-child dyads includes rich behavioral and developmental information and reliable scales on mother-child interactions that would not have been less available in a random or population-based sample of parents (O’Donnell et al., 2014). Second, the current study was cross-sectional, which limits causal inferences about the buffering effects of social capital over time and between generations. Still, very few studies have had dyadic data on mother-child health and distinguished between social capital and social support measures of social resources. Future research might build from these cross-sectional findings and employ longitudinal designs to establish the buffering role of social capital over time. While this work elucidates how maternal stress influences children’s emotional overeating, the influence of paternal stress on children’s emotional overeating is a question for future research. Third, our measure of social capital was based exclusively on the construct of network diversity, which has been shown in previous studies to be correlated with health (Ali et al., 2018). In ancillary sensitivity analyses of our position generator measures, we found that (i) other position-generator based measures of social capital (e.g., upper reachability) were not associated with children’s emotional overeating and (ii) our results remained robust when physicians and nurses were excluded from participant’s diversity count. Finally, our study focused on the mothers’ overall social support and not specific types of support that they may have received. In ancillary sensitivity analyses, we examined the importance of each type separately, with only emotional support significantly associated with children’s emotional overeating. However, inclusion of emotional support in the model alone did not alter the study’s findings. Furthermore, our study focused on received, and not perceived, support. Research has shown perceived support to be more consistently associated with health outcomes than received support (Uchino, 2004; Uchino, 2009; Saegert and Carpiano, 2017). Different results may have been seen had measures of perceived support been available and used.

Conclusions

This study brings new insight to the study of social capital by demonstrating the importance of network diversity in buffering the adverse impact of maternal stress on children’s emotional overeating. Findings suggest that social capital and social support may be different constructs, and that the benefits of social capital for health may be extended from parents to their children. Interventions aimed at child health outcomes such as emotional overeating should consider how modifiable social resources like social capital are and whether programs and policies might be used to interrupt the intergenerational transmission of stress. By situating the health benefits of social capital within an intergenerational context, our study aims to contribute to a broader understanding of the potential role of social capital in the production and reproduction of health inequalities.

Highlights.

Parental stress linked to children’s overeating in mothers with low social capital.

Health benefits of social capital extend from mother’s social networks to children.

Social capital and social support may provide different stress-buffering resources.

Interventions for child health should consider improving parental social capital.

Acknowledgements:

The MAVAN study was funded by several grants from Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), including a CIHR trajectory grant (191827) to principal investigators Dr. Meaney and Dr. Matthews, a grant from the National Institute of Health (NIH) (Grant no. 10213), as well as private support from the Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, the Norlien Foundation (Calgary, Alberta), and the Woco Foundation (London, Ontario). Dr. Levitan acknowledges support from the Cameron Holcombe Wilson Chair in Depression studies, CAMH and University of Toronto.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ali T, Nilsson CJ, Weuve J, Rajan KB, & Mendes De Leon CF (2018). Effects of social network diversity on mortality, cognition and physical function in the elderly: A longitudinal analysis of the Chicago Health and Aging Project (CHAP). Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health,72(11), 990–996. doi: 10.1136/jech-2017-210236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft J, Semmler C, Carnell S, Jaarsveld CH, & Wardle J (2007). Continuity and stability of eating behaviour traits in children. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition,62(8), 985–990. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek RN, Tanenbaum ML, & Gonzalez JS (2014). Diabetes Burden and Diabetes Distress: the Buffering Effect of Social Support. Annals of Behavioral Medicine,48(2), 145–155. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9585-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin CE (2009). Social capital and health status: Assessing whether the relationship varies between blacks and whites. Psychology & Health, 24(1), 109–118. doi: 10.1080/08870440701700997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, & Seeman TE (2000). From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science & Medicine,51(6), 843–857. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JO, & Jones WH (1995). The Parental Stress Scale: Initial Psychometric Evidence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships,12(3), 463–472. doi: 10.1177/0265407595123009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P (1986). Forms of Capital In Richardson JG (Ed.), Handbook of theory for the sociology of education(pp. 241–258). Westport, CT: Greenwood Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen KS, Uchino BN, Birmingham W, Carlisle M, Smith TW, & Light KC (2014). The stress-buffering effects of functional social support on ambulatory blood pressure. Health Psychology,33(11), 1440–1443. doi: 10.1037/hea0000005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers ME, & Yehuda R (2016). Intergenerational Transmission of Stress in Humans. Neuropsychopharmacology,41(1), 232–244. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron AC and Trivedi PK (2009). Microeconometrics Using Stata. College Station, TX: Stata Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carnell S, & Wardle J (2007). Measuring behavioural susceptibility to obesity: Validation of the child eating behaviour questionnaire. Appetite,48(1), 104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.07.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpiano RM, & Hystad PW (2011). ‘Sense of community belonging’ in health surveys: what social capital is it measuring? Health & Place, 17(2), 606–617. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpiano RM, & Kimbro RT (2012). Neighborhood Social Capital, Parenting Strain, and Personal Mastery among Female Primary Caregivers of Children. Journal of Health and Social Behavior,53(2), 232–247. doi: 10.1177/0022146512445899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, & Wills TA (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.98.2.310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS (1998). Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. Knowledge and Social Capital, 94, S95–S120. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-7506-7222-1.50005-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Croker H, Cooke L, & Wardle J (2011). Appetitive behaviours of children attending obesity treatment. Appetite,57(2), 525–529. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.05.320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyranowski JM, Zill N, Bode R, Butt Z, Kelly MA, Pilkonis PA, Salsman JM, & Cella D (2013). Assessing social support, companionship, and distress: National Institute of Health (NIH) Toolbox Adult Social Relationship Scales. Health Psychology, 32(3), 293–301. doi: 10.1037/a0028586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domoff SE, Miller AL, Kaciroti N, & Lumeng JC (2015). Validation of the Childrens Eating Behaviour Questionnaire in a low-income preschool-aged sample in the United States. Appetite,95, 415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eloranta A, Lindi V, Schwab U, Tompuri T, Kiiskinen S, Lakka H, Laitinen T, & Lakka TA (2012). Dietary factors associated with overweight and body adiposity in Finnish children aged 6–8 years: the PANIC Study. International Journal of Obesity,36(7), 950–955. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto K, Wang P, Ross MW, & Williams ML (2015). Venue-Mediated Weak Ties in Multiplex HIV Transmission Risk Networks Among Drug-Using Male Sex Workers and Associates. American Journal of Public Health, 105(6), 1128–1135. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2014.302474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon B, Harris D, & Harris M (2014). Threshold Effects In Nonlinear Models With An Application To The Social Capital-Retirement-Health Relationship. Health Economics,23(9), 1072–1083. doi: 10.1002/hec.3088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garasky S, Stewart SD, Gundersen C, Lohman BJ, & Eisenmann JC (2009). Family stressors and child obesity. Social Science Research,38(4), 755–766. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens L, Braet C, Vlierberghe LV, & Mels S (2009). Loss of control over eating in overweight youngsters: The role of anxiety, depression and emotional eating. European Eating Disorders Review,17(1), 68–78. doi: 10.1002/erv.892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb BH, & Bergen AE (2010). Social support concepts and measures. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 69(5), 511–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter M (1973). The Strength of Weak Ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(May), 1360–1380. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson PE, Sebastian MS, Janlert U, Theorell T, Westerlund H, & Hammarström A (2014). Life-Course Accumulation of Neighborhood Disadvantage and Allostatic Load: Empirical Integration of Three Social Determinants of Health Frameworks. American Journal of Public Health,104(5), 904–910. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2013.301707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpham T, De Silva MJ, & Tuan T (2006). Maternal social capital and child health in Vietnam. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60, 865–871. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.044883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda A, Iso H, Kawachi I, Yamagishi K, Inoue M, & Tsugane S (2008). Social Support and Stroke and Coronary Heart Disease: The JPHC Study Cohorts II. Stroke,39(3), 768–775. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.107.496695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay K, & Andersen LL (2018). Can high social capital at the workplace buffer against stress and musculoskeletal pain? Medicine,97(12). doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000010124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, & Umberson D (2015). Gender, stress in childhood and adulthood, and trajectories of change in body mass. Social Science & Medicine,139, 61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin N (1999). Social Networks and Status Attainment. Annual Review of Sociology, 25:467–87. [Google Scholar]

- Lin N (2001). Social capital: a theory of social structure and action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lin N, & Dumin M (1986). Access to occupations through social ties. Social Networks,8(4), 365–385. doi: 10.1016/0378-8733(86)90003-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mackler JS, Kelleher RT, Shanahan L, Calkins SD, Keane SP, & Obrien M (2015). Parenting Stress, Parental Reactions, and Externalizing Behavior From Ages 4 to 10. Journal of Marriage and Family,77(2), 388–406. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden PV (1987). Core Discussion Networks of Americans. American Sociological Review,52(1), 122. doi: 10.2307/2095397 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney MJ (2001). Maternal Care, Gene Expression, and the Transmission of Individual Differences in Stress Reactivity Across Generations. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 24(1), 1161–1192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E, & Parker KJ (2011). Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: Moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin,137(6), 959–997. doi: 10.1037/a0024768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mithen J, Aitken Z, Ziersch A, & Kavanagh AM (2015). Inequalities in social capital and health between people with and without disabilities. Social Science & Medicine, 126, 26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore S, Bockenholt U, Daniel M, Frohlich K, Kestens Y, & Richard L (2011). Social capital and core network ties: A validation study of individual-level social capital measures and their association with extra- and intra-neighborhood ties, and self-rated health. Health & Place, 17(2), 536–544. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore S, Stewart S, & Teixeira A (2013). Decomposing social capital inequalities in health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 68(3), 233–238. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-202996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore S, Teixeira A, & Stewart S (2016). Do age, psychosocial, and health characteristics alter the weak and strong tie composition of network diversity and core network size in urban adults? SSM - Population Health, 2, 623–631. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy E, Moore S, Gruber R, Paquet C, Arora N, & Dubé L (2016). Parental social capital and children’s sleep disturbances. Sleep Health,2(4), 330–334. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2016.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Michel ST, Unger JB, & Spruijt-Metz D (2007). Dietary correlates of emotional eating in adolescence. Appetite,49(2), 494–499. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell KA, Gaudreau H, Colalillo S, Steiner M, Atkinson L, Moss E, Goldberg S., Karama S., Matthews SG, Lydon JE, Silveira PP, Wazana AD, Levitan RD, Sokolowski MB, Kennedy JL, Fleming A, Meaney MJ; MAVAN Research Team (2014). The Maternal Adversity, Vulnerability and Neurodevelopment Project: Theory and Methodology. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry,59(9), 497–508. doi: 10.1177/070674371405900906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks EP, Kumanyika S, Moore RH, Stettler N, Wrotniak BH, & Kazak A (2012). Influence of Stress in Parents on Child Obesity and Related Behaviors. Pediatrics,130(5). doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI (1999). The Stress Process Revisited: Reflections on Concepts and Their Interrelationships In Aneshensel CS & Phelan JC (Eds.), Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health (pp. 395–415). New York: Springer. doi: 10.1007/0-387-36223-1_19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puder JJ, & Munsch S (2010). Psychological correlates of childhood obesity. International Journal of Obesity,34. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reczek C, & Zhang Z (2016). Parent-child relationships and parent psychological distress: How do social support, strain, dissatisfaction, and equity matter? Research on Aging, 38(7), 742–766. doi: 10.1177/0164027515602315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth DL, Brown SL, Rhodes JD, & Haley WE (2018). Reduced mortality rates among caregivers: Does family caregiving provide a stress-buffering effect? Psychology and Aging. doi: 10.1037/pag0000224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saegert S, & Carpiano RM (2017). Social support and social capital: A theoretical synthesis using community psychology and community sociology approaches. APA handbook of community psychology: Theoretical foundations, core concepts, and emerging challenges. ,295–314. doi: 10.1037/14953-014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santos JL, Ho-Urriola JA, González A, Smalley SV, Domínguez-Vásquez P, Cataldo R, Obregón AM, Amador P, Weisstaub G, & Hodgson MI (2011). Association between eating behavior scores and obesity in Chilean children. Nutrition Journal,10(1). doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-10-108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira P, Portella A, Kennedy J, et al. (2014). Association between the seven-repeat allele of the dopamine-4 receptor gene (DRD4) and spontaneous food intake in pre-school children. Appetite, 73, 15–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, & Lin N (2009). Social Capital and Health Inequality: Evidence from Taiwan. Journal of Health and Social Behavior,50(2), 149–163. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Story WT, & Carpiano RM (2017). Household social capital and socioeconomic inequalities in child undernutrition in rural India. Social Science & Medicine,181, 112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA (2011). Mechanisms Linking Social Ties and Support to Physical and Mental Health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior,52(2), 145–161. doi: 10.1177/0022146510395592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toepfer P, Heim C, Entringer S, Binder E, Wadhwa P, & Buss C (2017). Oxytocin pathways in the intergenerational transmission of maternal early life stress. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews,73, 293–308. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.12.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JR, Turner B, & Hale WB (2014). Social Relationships and Social Support In Johnson RJ, Turner RJ, & Link BG (Eds.), Sociology of Mental Health: Selected Topics from Forty Years 1970s-2010s(pp. 1–20). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN (2004). Social support and physical health understanding the health consequences of relationships. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN. (2006). Social Support and Health: A Review of Physiological Processes Potentially Underlying Links to Disease Outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29:377–87. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN (2009). Understanding the Links Between Social Support and Physical Health: A Life-Span Perspective With Emphasis on the Separability of Perceived and Received Support. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(236), 236–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01122.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Pudrovska T, & Reczek C (2010). Parenthood, Childlessness, and Well-Being: A Life Course Perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 612–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00721.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J, Guthrie CA, Sanderson S, & Rapoport L (2001). Development of the Childrens Eating Behaviour Questionnaire. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 42(1), 963–970. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber L, Hill C, Saxton J, Jaarsveld CH, & Wardle J (2009). Eating behaviour and weight in children. International Journal of Obesity,33(1), 21–28. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weil F, Lee MR, & Shihadeh ES (2012). The burdens of social capital: How sociallyinvolved people dealt with stress after Hurricane Katrina. Social Science Research,41(1), 110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda R, Bell A, Bierer LM, & Schmeidler J (2008). Maternal, not paternal, PTSD is related to increased risk for PTSD in offspring of Holocaust survivors. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 42(12), 1104–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]