Abstract

The gut microbiota has been evolving with its host along the time creating a symbiotic relationship. In this study, we assess the role of the host genome in the modulation of the microbiota composition in pigs. Gut microbiota compositions were estimated through sequencing the V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene from rectal contents of 285 pigs. A total of 1,261 operational taxonomic units were obtained and grouped in 18 phyla and 101 genera. Firmicutes (45.36%) and Bacteroidetes (37.47%) were the two major phyla obtained, whereas at genus level Prevotella (7.03%) and Treponema (6.29%) were the most abundant. Pigs were also genotyped with a high-throughput method for 45,508 single nucleotide polymorphisms that covered the entire pig genome. Subsequently, genome-wide association studies were made among the genotypes of these pigs and their gut microbiota composition. A total of 52 single-nucleotide polymorphisms distributed in 17 regions along the pig genome were associated with the relative abundance of six genera; Akkermansia, CF231, Phascolarctobacterium, Prevotella, SMB53, and Streptococcus. Our results suggest 39 candidate genes that may be modulating the microbiota composition and manifest the association between host genome and gut microbiota in pigs.

Subject terms: Microbial ecology, Metagenomics, Genetic markers, Genome-wide association studies

Introduction

The digestive tract of animals has been evolving along the time with symbiotic microorganisms. These microbes, mostly bacteria, have adapted to thrive in such conditions forming complex and vital interactions among them and their host1,2. The ecological community of these microorganisms is called microbiome, and the interactions with the host can be commensal, pathogenic or mutualistic3. In this scenario, mutualistic gut microbiota provides the host with beneficial functions that the host cannot perform, such as digesting complex polysaccharides, producing vitamins, and preventing colonization by pathogens2,4. Likewise, commensal gut populations modulate hosts’ immune responses which can modify the microbiota composition in order to maintain gut homeostasis4. Therefore, apart from the host genetics, the complexity of the interactions increases taking into account factors such as age, diet, environment, disease, or maternal seeding which are known to influence gut microbial communities5.

The intestinal epithelium acts as a barrier, protecting deeper tissues from bacterial entry2. Supporting this defence system, the gut epithelial surface is coated with a mucous layer formed by mucin glycoproteins6,7. While the small intestine has only one layer which is permeable to bacteria6, the mucous layer of the colon is structured in two parts: a dense inner layer firmly attached to the gut epithelium that minimizes bacterial-epithelial cell contact, and a loose outer layer that can be broken down by commensal bacteria7. In this outer mucous layer, the metabolites produced by these bacteria interact with the host stimulating the innate and adaptive immune responses2. For instance, host innate immunity can select for a species-specific microbiota using microbicidal proteins8. However, the host also has mechanisms to tolerate the metabolites from non-pathogenic bacteria2, just as certain bacteria trigger the host immune system for self-benefit9.

In these recent years, high-throughput sequencing technologies have greatly improved the study of bacterial populations without performing microbial cultures. The microbial 16S rRNA gene sequencing is commonly used to estimate the microbiota composition, while the shotgun sequencing of DNA fragments isolated after shearing faecal or other samples is used for the metagenome (all the microbial collective genomes) characterization10. Recently, whole-metagenome sequencing has been used to obtain the reference gene catalogue of the pig gut microbiome11. This study revealed that the reference catalogue of the porcine gut microbiome shared more non-redundant genes between human and pig than human and mouse11, suggesting pig as a better animal model than mouse because of their similarity with humans. Both species are omnivores and have monogastric digestive tracts which are analogous in anatomy, immunology and physiology12.

The heritability of the microbial genera composition of the pig gut has been reported to range from low to high values13,14. Accordingly, host genetics has been suggested as an important factor in the determination of gut microbial composition15. However, there are limited studies measuring the contribution of inter-individual variability modulating the bacterial communities and the effect of host polymorphisms on the establishment of the microbiota16. In this context, genome-wide association studies (GWAS), which have been widely used to analyse a plethora of complex traits, are now being used to study the link between the host and its microbiota composition15,16. With this approach, Blekhman et al.17 were the first to describe in humans the relationship between the abundance of Bifidobacterium and the single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) close to the lactase gene. In this case, lactase non-persistent recessive individuals who drink milk cannot break down lactose and thus, Bifidobacterium thrives using this available sugar18.

Conversely, host genetics appeared to have a minor impact in the microbiota compared with age, diet or the environment19. It is not surprising, since conditions are difficult to standardize between individuals. In this regard, production pigs represent a perfect model to measure the effect of host genetics in shaping the microbiota due to their similar diet and environmental factors during their whole rearing cycle, but the relationship between the pig genome and its gut microbiota composition has not yet been fully described20.

The objective of this study was to identify genomic regions that influence the gut microbiota composition through host-microbiota associations in pigs. For this purpose, the 16S rRNA gene was sequenced from rectal contents of 288 pigs genotyped with a high-throughput method.

Materials and Methods

Ethics approval

All animal manipulations were performed according to the regulations of the Spanish Policy for Animal Protection RD53/2013, which meets the European Union Directive 2010/63/EU about the protection of animals used in experimentation. Pigs were slaughter in a commercial abattoir following national and institutional guidelines for Good Experimental Practices.

Animal material

A total of 288 healthy commercial F1 crossbred pigs (Duroc × Iberian) were used in this study. All animals were maintained in the same farm under intensive conditions and feeding was ad libitum with a barley- and wheat-based commercial diet. Pigs with an average weight of 138.8 kg (SD = 11.46 kg) were slaughtered in a commercial abattoir in four distinct days. Samples of rectal content and Longissimus dorsi muscle were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and later stored at −80 °C.

Microbial DNA extraction and 16S rRNA gene sequencing

For each one of the 288 samples, the DNA of 0.2 g of rectal content was extracted with PowerFecal kit (MoBio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. DNA purity and concentration were measured through a ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). The amplification of the V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was performed following the recommendations of the 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation guide (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Full description of primer sequences and methods used can be accessed at Supplementary Information S1. All the 288 amplicon pooled libraries were sequenced in three runs of a MiSeq (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) instrument in the Sequencing Service of the FISABIO (Fundació per al Foment de la Investigació Sanitària i Biomèdica de la Comunitat Valenciana, Valencia, Spain) using the MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (600-cycle format, 2 × 300 bp paired-end reads). A mean of 104,115 reads for each sample was obtained (17.991 Gb in total), ranging from 34,186 to 218,360 reads, except for one outlier that was discarded because it had 1,758,983 reads.

Taxonomy classification and diversity studies of the gut samples

Bioinformatics analysis were performed in QIIME v.1.9.121 by using the QIIME’s subsampled open-reference operational taxonomic unit (OTU) calling approach and following the recommendations of Rideout et al.22. In brief, the join_paired_ends.py function in QIIME was used to merge the forward and reverse reads contained in the fastq files of the remaining 287 samples. The quality control and the filtering process was made pursuant to the considerations provided by Bokulich et al.23. Therefore, the split_libraries_fastq.py command was used to demultiplex and filter (at Phred ≥ Q20) the fastq sequence data. After this step, OTUs were identified by using the pick_open_reference_otus.py function with a subsampled percentage of 10% (s = 0.1). Subsequently, chimera detection was carried on in QIIME with BLAST24 and OTUs were taxonomically annotated employing the Greengenes 13.8 database25. At this point, two samples did not satisfy the quality filters and were discarded. Thus, for the remaining 285 samples, a dataset containing 1,294 OTUs was obtained after filtering out singletons and OTUs representing less than 0.005% of the total number of annotated reads23. From this dataset, 33 OTUs had missing taxonomic ranks and were discarded. Finally, 1,261 OTUs in the 285 samples were considered for further analysis (Supplementary Table S1).

The 1,261 OTUs were grouped in 18 phyla and 101 genera through the tax_glom method within the phyloseq package26 in R (www.r-project.org). Besides, genera that belonged to a higher taxonomy rank but lacked the genus information were merged and marked as unspecified (g__unsp).

The analyses of α and β-diversities in the 285 samples were carried on with the vegan R package27, and the non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plot was performed using phyloseq26 and ggplot228. For the α-diversity study, the Shannon index was employed, whereas the β-diversity study was represented using the Whittaker index. Additionally, the dissimilarity between pairs of samples was estimated with the NMDS method using the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity29.

Host DNA extraction and SNP genotyping

Pig genomic DNA was extracted from the Longissimus dorsi muscle of all the 288 samples using the standard phenol-chloroform method30. The DNA concentration and purity was measured with a ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop) afterwards.

A total of 288 pigs were genotyped with the GeneSeek Genomic Profiler (GGP) Porcine HD v1 (70 K) array (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) using the Infinium HD Assay Ultra protocol (Illumina). Genotypes were obtained with the GenomeStudio software (2011.1 version, Illumina) and filtered with the PLINK software31 (1.90b5 version). Further analyses were conducted using only SNPs that mapped in the Sscrofa11.1 assembly, with a minor allele frequency (MAF) >5% and missing genotypes <5%, retaining a total of 45,508 SNPs.

GWAS analysis

For the 285 samples, GWAS between the microbiota composition at genus level and the 45,508 genotyped SNPs were made. Samples were normalized in percentages based on the number of annotated reads per sample (relative abundance). To avoid errors caused by low abundant genera, GWAS were performed only in genera that comprised more than the 0.5% of the total annotated reads and were present in more than the 90% of the samples. In addition, genera marked as unspecified were excluded from the GWAS analysis. Therefore, GWAS were performed in 18 of the 101 genera found.

For the GWAS analysis, the following univariate linear mixed model was applied using the GEMMA software32 (0.96 version):

where yijkl indicates the vector of phenotypic observations in the kth individual; sex (two categories) and batch (4 categories) are fixed effects; uk is the infinitesimal genetic effect considered as random and distributed as N(0, Kσu), where K is the numerator of the kinship matrix; δk is a −1, 0, +1 indicator variable depending on the kth individual genotype for the lth SNP; al represents the additive effect associated with the lth SNP; and eijkl is the residual.

The false discovery rate (FDR) method developed by Benjamini and Hochberg33 was applied for multiple test correction using the p.adjust function incorporated in R. The cut-off for considering a SNP as significant was set at FDR ≤ 0.1. Two significant SNPs were grouped inside the same interval if the distance between them was less than 2 Mb.

Gene annotation and functional prediction

The associated regions in the pig genome were annotated at 1 Mb on each side of the previously defined intervals. The genes contained in these regions were extracted using the BioMart tool34 from the Ensembl project (www.ensembl.org; release 92) using the Sscrofa11.1 reference assembly. In addition, the functional consequences of the significant SNPs were predicted through the Variant Effect Predictor tool35 from the Ensembl project (release 92).

Results and Discussion

Microbiota composition and diversity

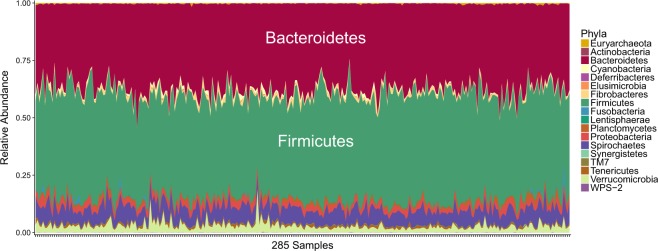

A mean of 104,115 reads per sample were obtained with a MiSeq (Illumina) after sequencing the V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene from rectal contents of 288 pigs. A total of 1,261 OTUs which were grouped in 18 phyla and 101 genera were found in the 285 samples that fulfilled the quality criteria. At phylum level, Firmicutes (45.36%) and Bacteroidetes (37.47%) were the more abundant (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S2). In accordance with the literature36,37, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes are usually the most dominant phyla found in colon and faeces of pigs. The most abundant genera, not marked as unspecified, were Prevotella (7.03%) and Treponema (6.29%) (Supplementary Table S3). Accordingly, Prevotella spp. are frequently found as one of the most abundant genus in the lower intestine and faeces36,37. However, comparisons between different studies should be made with caution, since differences in microbiota composition are conditional on the different sets of primers used in the analysis, breeds (host genetic background), age of the animals at sampling time, and environmental factors such as dietary composition14,38.

Figure 1.

Stacked area plot of OTUs grouped by phyla for the 285 pig rectal samples.

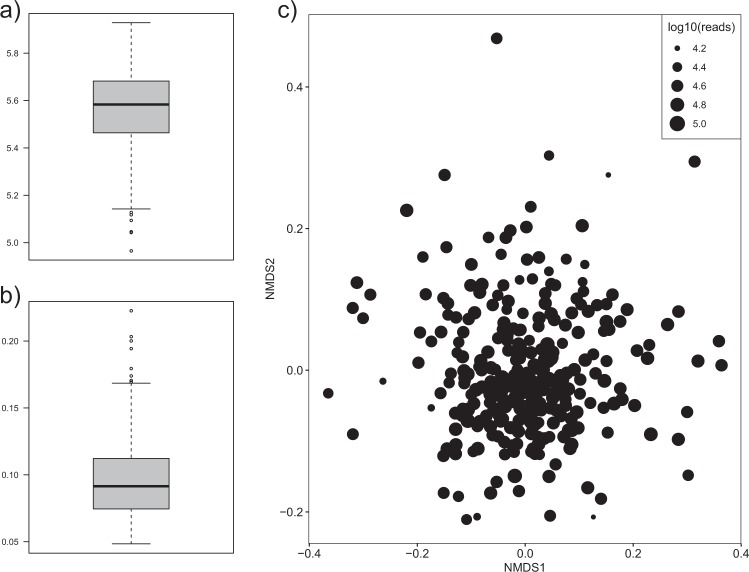

To obtain a measure for the number of different OTUs and their relative abundance within each of the 285 samples, the community α-diversity was calculated through the Shannon index (Fig. 2a). The mean of the α-diversity was 5.55, ranging from 4.97 to 5.93. It is not surprising, since the distal part of the pig gut usually has a higher α-diversity than the rest of the intestine37. In addition, the β-diversity was used to measure the differences between samples through the Whittaker index (Fig. 2b) obtaining a mean distance to the centroid of 0.10. Lastly, a NMDS plot was performed to observe the dissimilarities between samples employing Bray-Curtis dissimilarity (Fig. 2c). The β-diversity was closer to 0, indicating that the global microbiota composition was quite similar along the 285 samples. Furthermore, this low β-diversity was expected, since the pigs from our study have been subjected to the same diet and environmental factors during their whole rearing cycle and this uniformity is reinforced by the absence of clustering in the NMDS plot. This way, overall diversity results reinforce the appropriateness of the model to measure the effect of host genetics in shaping the microbiota.

Figure 2.

Plots showing the diversities and dissimilarities measured using the 1,261 OTUs found in rectal contents of 285 pigs. (a) Boxplot of the Shannon α-diversity. (b) Boxplot of the Whittaker β-diversity calculated through the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity. (c) Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plot based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarities. The size of the dot is proportional to the total number of annotated reads in each sample.

GWAS results

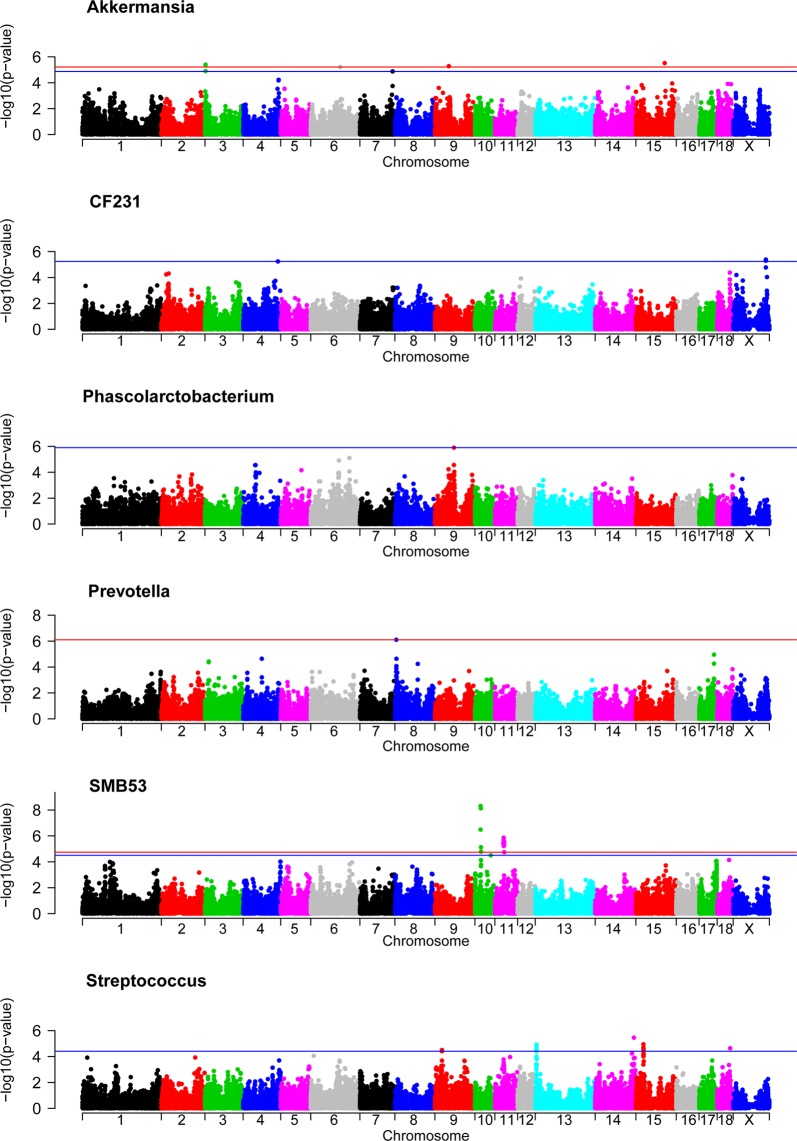

GWAS were performed using 45,508 SNPs genotyped in 285 animals and the relative abundance of 18 genera; Akkermansia, Bacteroides, CF231, Coprococcus, Fibrobacter, Lactobacillus, Oscillospira, Parabacteroides, Paraprevotellaceae Prevotella, Phascolarctobacterium, Prevotella, RFN20, Ruminococcus, SMB53, Sphaerochaeta, Streptococcus, Treponema and YRC22. A total of 52 significant SNPs were distributed in 17 regions along the following Sus scrofa chromosomes (SSC): SSC3, SSC4, SSC6, SSC7, SSC8, SSC9, SSC10, SSC11, SSC13, SSC14, SSC15, SSC18 and SSCX (Supplementary Table S4). Significant association signals (FDR ≤ 0.1) were found in six out of the 18 GWAS for the following genera: Akkermansia, CF231, Phascolarctobacterium, Prevotella, SMB53 and Streptococcus (Fig. 3 and Table 1). No shared associated regions were found for the abundances of these six genera, albeit some of them belong to the same phyla. CF231 and Prevotella are genera of the Bacteroidetes phylum. Within the Firmicutes phylum, Phascolarctobacterium and SMB53 are members of the Clostridiales order, and Streptococcus is a member of the Lactobacillales order. Hence, our results suggest an association between chromosomal regions along the pig genome and abundance of certain bacteria genera. In the following sections, the candidate genes mapped in the genomic regions associated with the genus relative abundance of Akkermansia, CF231, Phascolarctobacterium, Prevotella, SMB53 and Streptococcus are discussed in detail. The list of candidate genes is summarized in Table 1.

Figure 3.

GWAS plot for the relative abundance of the following genera: Akkermansia, CF231, Phascolarctobacterium, Prevotella, SMB53, and Streptococcus. The red lines indicate those SNPs that are below the genome-wide significance threshold (FDR ≤ 0.05), while the blue lines indicate those SNPs that are below genome-wide significance threshold (FDR ≤ 0.1).

Table 1.

Significant genomic regions in the pig genome associated with the relative composition of genera and the candidate genes found within.

| Region | Genus | Chr.a | Position in Mb Start - End | No. SNPsb | Most significant SNP | Effect (%) | p-value | FDR | Candidate genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Akkermansia | 3 | 0.89–3.04 | 3 | rs81335357; rs81246645 | 7.72 | 4.04 × 10−6 | 4.58 × 10−2 | CARD11; CHST12 |

| A2 | Akkermansia | 6 | 101.46–103.46 | 1 | rs81390429 | 25.85 | 6.06 × 10−6 | 4.58 × 10−2 | TGIF1 |

| A3 | Akkermansia | 7 | 112.61–114.61 | 1 | rs325604118 | 6.56 | 1.33 × 10−5 | 7.55 × 10−2 | LGMN; CHGA |

| A4 | Akkermansia | 9 | 47.53–49.57 | 2 | rs81410866; rs81410881 | 8.78 | 5.25 × 10−6 | 4.58 × 10−2 | ssc-mir-125b-1; ssc-mir-100; SORL1 |

| A5 | Akkermansia | 15 | 99.10–101.10 | 1 | rs80982646 | 7.94 | 3.04 × 10−6 | 4.58 × 10−2 | SLC39A10 |

| B1 | CF231 | 4 | 119.91–121.91 | 1 | rs319005051 | 7.07 | 5.72 × 10−6 | 6.48 × 10−2 | |

| B2 | CF231 | X | 112.48–114.50 | 3 | rs329229283 | 6.34 | 4.10 × 10−6 | 6.48 × 10−2 | FGF13; ATP11C |

| C1 | Phascolarctobacterium | 9 | 65.33–67.33 | 1 | rs81223434 | 7.73 | 1.25 × 10−6 | 5.68 × 10−2 | SLC45A3; RAB7B; RAB29; NUCKS1; IKBKE; MAPKAPK2 |

| D1 | Prevotella | 8 | 3.81–5.81 | 1 | rs326174858 | 10.88 | 7.79 × 10−7 | 3.53 × 10−2 | CYTL1; WFS1; MAN2B2 |

| E1 | SMB53 | 10 | 18.51–22.05 | 5 | rs344136854 | 14.25 | 4.92 × 10−9 | 1.68 × 10−4 | CAPN8; CAPN2; SUSD4; DENND1B; PTPRC; ssc-mir-181b-1; ssc-mir-181a-1 |

| E2 | SMB53 | 10 | 53.89–55.89 | 1 | rs341165563 | 8.87 | 3.15 × 10−5 | 7.14 × 10−2 | MALRD1 |

| E3 | SMB53 | 11 | 28.22–33.50 | 14 | rs80835110 | 10.42 | 1.37 × 10−6 | 1.47 × 10−2 | PCDH17 |

| F1 | Streptococcus | 9 | 23.45–25.66 | 3 | rs319168851 | 6.15 | 3.11 × 10−5 | 9.41 × 10−2 | FAT3 |

| F2 | Streptococcus | 13 | 2.97–5.15 | 4 | rs81310237 | 11.88 | 1.20 × 10−5 | 9.41 × 10−2 | PLCL2; GALNT15; RFTN1 |

| F3 | Streptococcus | 14 | 133.80–135.80 | 1 | rs337448241 | 10.51 | 3.46 × 10−6 | 9.41 × 10−2 | CTBP2; UROS |

| F4 | Streptococcus | 15 | 25.15–27.87 | 9 | rs331341379 | 8.72 | 1.12 × 10−5 | 9.41 × 10−2 | ERCC3; BIN1; MAP3K2 |

| F5 | Streptococcus | 18 | 44.25–46.25 | 1 | rs334064749 | 7.7 | 2.26 × 10−5 | 9.41 × 10−2 | ssc-mir-196b-1 |

aChromosome.

bNumber of significant SNPs found in the region (FDR ≤ 0.1).

Akkermansia

The relative abundance of Akkermansia, a genus of the Verrucomicrobia phylum, was significantly associated with polymorphisms in five chromosomic regions: SSC3, SSC6, SSC7, SSC9, and SSC15 (Table 1). Within the SSC3 region (1.03–3.04 Mb), two candidate genes have been proposed, caspase recruitment domain family member 11 (CARD11) and carbohydrate sulfotransferase 12 (CHST12). CARD11 is necessary for T helper 17 cells differentiation which are involved in the adaptive immune system and protect the body against extracellular bacteria39. The CHST12 gene is required for glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis40. Glycosaminoglycans are also called mucopolysaccharides and are often found in the mucin layer together with glycans and sialic acid41. The most common species of the Verrucomicrobia phylum found in the gut, Akkermansia muciniphila, colonizes the mucus layer and it is a known mucin degrader42. The regulation of host genes related to glycosaminoglycans biosynthesis probably has a direct effect in the occurrence of mucin degrading bacteria. Studying further this candidate gene may help to select a genetic variant that enriches the presence of A. muciniphila, since this species is beneficial to the host by restoring gut barrier function and helps reducing obesity43. In SSC6 (102.46 Mb), the only significant SNP (rs81390429, p-value = 6.06 × 10−6) explained a 25% of the variance in the abundance of the Akkermansia genus. The candidate gene found in this SSC6 region, TGIF1 (TGFB induced factor homeobox 1), encodes for a protein that contributes to the adaptive immunity favouring the response of T follicular helper cells44. Additionally, two candidate genes were proposed for the Akkermansia spp. abundance in the SSC7 region (112.61–114.61 Mb): CHGA (chromogranin A) and LGMN (legumain). In humans, faecal levels of CHGA were associated with 61 different bacterial species including A. muciniphila, which was negatively associated with CHGA45. CHGA plays a role in the innate immunity with its antimicrobial activity against bacteria46, whereas LGMN is a cysteine protease that also has antimicrobial activity, as well as it is involved in the antigen-presenting process and Toll-like receptors (TLRs) activation47. Thus, variations in the CHGA or LGMN genes should be affecting the microbiota composition based on the bacterial resistance to their antimicrobial activity. Inside the SSC9 region (47.53–49.57 Mb), there were three candidate genes, two microRNAs genes, ssc-mir-125b-1 and ssc-mir-100, and the sortilin related receptor 1 (SORL1) gene. Both microRNAs are involved with the adaptive immune system: miR-125b-1 inhibits B cell differentiation48, while miR-100 inhibits T cell proliferation and differentiation49. Therefore, polymorphisms in these miRNAs genes may affect the targeting of these miRNAs or their expression, which might be associated with the abundance of Akkermansia spp. However, the two significant SNPs (rs81410866 and rs81410881, p-value = 5.25 × 10−6) of the SSC9 region were located in intronic regions of the SORL1 gene. SORL1 is an endocytic receptor that might be affecting gut microbiota composition as it has been associated with obesity50, and pancreatic and biliary tract cancer in humans51. Finally, a significant SNP (rs80982646, p-value = 3.04 × 10−6) located at 100.1 Mb in SSC15 was also associated with the relative abundance of Akkermansia spp. In this region, we identified the SLC39A10 (solute carrier family 39 member 10) gene which appears to be a good candidate to modulate the presence of Akkermansia spp., since positively regulates B cell receptor signalling pathway52. Hence, in accordance with our results, germ-free mice colonized with A. muciniphila showed an overexpression in genes related with the antigen presentation pathway and B and T cell maturation, implying its possible role as host immune system modulator53.

CF231

The relative abundance of the CF231 genus (a member of the Paraprevotellaceae family) was associated to genetic variations in two regions along the pig genome in SSC4 and SSCX (Table 1). While no candidate genes were found in SSC4 at 120.91 Mb, the SSCX region (112.48–114.50 Mb) contained the ATPase phospholipid transporting 11 C (ATP11C) and the fibroblast growth factor 13 (FGF13) genes. The ATP11C protein is involved in B cell differentiation past the pro-B cell stage, thus, defects in ATP11C led to a lower number of B cells and an impairment in their differentiation54. Changes in the ATP11C gene may cause species-specific tolerance through the adaptive immune system and transport. Additionally, ATP11C is also involved in the metabolism of cholestatic bile acids55. Intestinal content of cholesterol has the potential to shape the gut microbiome56 and the CF231 genus might be affected by the expression of these genes, since bile acids are catabolites of cholesterol. Interestingly, an enrichment of the CF231 genus has been detected in experiments with high fat diet-induced hypercholesterolemic rats treated with cholesterol-lowering drugs57. On the other hand, the three significant SNPs of the SSCX region were located in an intron of the other candidate gene, FGF13 (Supplementary Table S4). Although the biological role of the FGF13 gene is not clear, it may be involved in the repair of the intestinal epithelial damage affecting microbiota composition. This function has been reported in another member of its gene family, FGF2 (fibroblast growth factor 2)58.

Phascolarctobacterium

Six candidate genes found inside the SSC9 region (65.33–67.33 Mb) may be associated with the relative abundance of Phascolarctobacterium spp. (Table 1). Phascolarctobacterium is a Gram-negative genus commonly found in human faeces able to produce short chain fatty acids (SCFAs)59. SCFAs are absorbed and serve as a source of energy by colonocytes and peripheral tissue or can be use as substrates for lipogenesis, gluconeogenesis or regulation of cholesterol synthesis in the liver60. Interestingly, one of the candidate genes that could be modulating the abundance of Phascolarctobacterium spp. was the SLC45A3 (solute carrier family 45 member 3). SLC45A3 is involved in the positive regulation of fatty acid biosynthetic process61. There were also two other candidate genes within SSC9 which encode GTPases that are members of the RAS oncogene family (RAB7B and RAB29). Under the induction of the lipopolysaccharides present in the Gram-negative cell wall, RAB7B promotes the degradation of toll like receptor 4 (TLR4) impairing the innate immune response by reducing the sensitivity of macrophages to lipopolysaccharides signalling62. Therefore, RAB7B may play an important role in the development of tolerance to Gram-negative commensal bacteria such as Phascolarctobacterium spp. The other GTPase, RAB29, is involved in bacterial toxin transport and is able to discriminate between Salmonella enterica serovars63. The positive regulation of insulin receptor signalling pathway by the NUCKS1 (nuclear casein kinase and cyclin dependent kinase substrate 1) gene64 located in this SSC9 region may also be modulating the abundance of the Phascolarctobacterium genus, since it has been described an enrichment of this genus in diabetic animal models treated with prebiotics to alleviate glucose intolerance60. Additionally, the two remaining candidate genes, IKBKE (inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa B kinase subunit epsilon) and MAPKAPK2 (mitogen-activated protein kinase-activated protein kinase 2) might be associated with the microbiota composition because of their relationship with the immune system. IKBKE inhibits T cell responses65 and MAPKAPK2 regulates interleukin 1066 which is crucial to maintain the gut homeostasis4.

Prevotella

Studies performed in humans have associated the presence of the Prevotella genus with a high intake of complex fibres in the diet67. In our animal material, Prevotella spp. represented 7.03% of the total composition at genus level (Supplementary Table S3). In this case, only the rs326174858 SNP located at 4.81 Mb in SSC8 was significantly associated (p-value = 7.79 × 10−7) with the abundance of Prevotella spp. (Table 1). Three candidate genes were found in this SSC8 region, cytokine like 1 (CYTL1), wolframin ER transmembrane glycoprotein (WFS1), and mannosidase alpha class 2B member 2 (MAN2B2). CYTL1 codes for a protein capable of chemoattracting macrophages and its activity is sensitive to Bordetella pertussis toxin68. A defect in the second gene, WFS1, produces insulin insufficiency, causing diabetes via pancreatic β cells failures69. Therefore, diabetic individuals would reduce glucose uptake in the gut epithelium70. In this sense, glucose might be more available for some bacteria species, producing changes in the overall microbiota composition. In accordance with this hypothesis, the abundance of Prevotella spp. was reduced in diabetic children when compared to healthy ones71. The encoded protein of the last candidate gene, MAN2B2, is implicated in the degradation of glycans72. Glycans are excreted into the intestine, including those in dietary plants, animal-derived, cartilage and tissue (glycosaminoglycans and N-linked glycans), and endogenous glycans from host mucus (O-linked glycans)73. The Prevotella genus contributes to the degradation of mucin and plant-based carbohydrates74 and, therefore, it seems plausible that variations in a gene involved in the degradation of glycans could modulate the presence of Prevotella spp.

SMB53

The SMB53 genus sequences found in swine compost were closely related with Clostridium glycolicum75. The abundance of the SMB53 genus in our pig rectal samples accounted for 1.19% of the total number of annotated reads (Supplementary Table S3), and presented three significant associated regions, two in SSC10 and one in SSC11 (Table 1). The first region of SSC10 (18.51–22.05 Mb) showed the most significant SNP (rs344136854, p-value = 4.92 × 10−9). Seven candidate genes have been identified inside this SSC10 region: calpain 2 (CAPN2) and 8 (CAPN8); sushi domain containing 4 (SUSD4); DENN domain containing 1B (DENND1B); protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type C (PTPRC); ssc-mir-181a-1 and ssc-mir-181b-1. Calpains are a family of proteases that are able to perform various cellular functions depending on changes in intracellular Ca2+ levels76. For instance, an increase in Ca2+ in the intestinal porcine endothelial cells due to the Clostridium perfringens β-toxin triggers the calpain activation leading to intestinal cell death77. Therefore, polymorphisms in the CAPN2 or CAPN8 genes may confer resistance to Clostridium spp. avoiding endothelial cell death and so, increasing Clostridia abundance in the gut. Two of the significant SNPs of this SSC10 region were located in an intron of the SUSD4 gene, whereas other significant SNP was also located in an intron of the DENND1B gene (Supplementary Table S4). SUSD4, DENND1B and PTPRC are genes related with the immune system: SUSD4 inhibits the complement system78, DENND1B is a regulator of the T cell receptor signalling79, and PTPRC is necessary for antigen receptor mediated signalling in lymphocytes80. The last two candidate genes in this first SSC10 region were both microRNAs from the miR-181 family. The depletion of miR-181 causes a lack of Natural Killer T cells in the thymus as well as defects in T and B cells development81. In the second SSC10 region (54.89 Mb), the only significant SNP (rs341165563, p-value = 3.15 × 10−5) was located in an intron of the MALRD1 (MAM and LDL receptor class A domain containing 1) gene (Supplementary Table S4). This candidate gene is involved in bile acid synthesis regulation and is able to modify the gut microbiota82. Khan et al.57 demonstrated an increase in the relative abundance of the SMB53 genus in hypercholesterolemic rats treated with cholesterol-lowering drugs. Thus, further studies are needed to evaluate the modulation of the SMB53 genus by the MALRD1 negative regulation of bile acid biosynthetic process. Additionally, the SMB53 genus belongs to the Clostridiaceae family. Most members of this family have the capacity to consume gut mucus- and plant-derived saccharides like glucose83. Interestingly, recent studies performed by Horie et al.84 have detected an enrichment of SMB53 in caecum of mice suffering type 2 diabetes, suggesting a possible role of this genus in the disease. The last region, in SSC11 (28.22–33.5 Mb), was comprised of 14 SNPs but, despite being the longest region observed (5.3 Mb), only one candidate gene (protocadherin 17, PCDH17) was proposed. Remarkably, the most significant SNP (rs80835110, p-value = 1.37 × 10−6) was located in an intron of PCDH17 (Supplementary Table S4). PCDH17 may play a role in the colon similar to protocadherin 1 (PCDH1), acting as a physical barrier in the airway epithelial cells85.

Streptococcus

There are five regions within the pig genome associated to the presence of Streptococcus spp., SSC9, SSC13, SSC14, SSC15, and SSC18 (Table 1). In the SSC9 region (23.45–25.66 Mb), the protein encoded by the FAT atypical cadherin 3 (FAT3) gene may be forming epithelial junctions that can be broken down by Streptococcus spp.86. In the SSC13 region (2.97–5.15 Mb), three candidate genes were found: phospholipase C like 2 (PLCL2), polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 5 (GALNT15), and raftlin, lipid raft linker 1 (RFTN1). Four significant SNPs were located in intronic regions of the PLCL2 gene (Supplementary Table S4). PLCL2 increases the thresholds of B cell activation87 and so, it may modulate the tolerance of the adaptive immune system. On the other hand, GALNT15 belongs to a family of proteins that are able to produce O-linked glycosylation in the mucin88 and hence, the variations on the GALNT15 gene might affect some mucin dwellers like Streptococcus spp.89. Additionally, it is also interesting to highlight a possible link between the RFTN1 gene, involved in the formation and/or maintenance of lipid rafts90, and the abundance of the Streptococcus genus. The lipid rafts are microdomains located in the membrane surface of the cell that play an important role in cellular signaling and membrane trafficking of T and B lymphocytes90,91. Furthermore, lipid rafts are also mediators of innate immune recognition of bacteria92. The possible association of RFTN1 with the abundance of Streptococci needs further attention, since some species of Streptococcus are known to hijack these lipid rafts to enter the host cell causing disease93. Two candidate genes were found in the SSC14 region (133.8–135.8 Mb): CTBP2 (C-terminal binding protein 2) and UROS (uroporphyrinogen III synthase). The CTBP2 gene was associated in pigs with a susceptibility to develop a bacterial respiratory disease94. The UROS gene is involved in the metabolism of porphyrins including heme and uroporphyrinogen III biosynthetic processes95. Iron in mammals is incorporated into heme; an essential component of the hemoglobin, which can be acquired by bacterial pathogens as a nutritional iron source. Several Streptococci species that are pathogenic to humans and animals, namely S. pyogenes, S. pneumoniae and S. suis, contain cell wall heme-binding proteins that allow them to scavenge heme from host’s hemoglobin as a source of iron acquisition96,97. Additionally, the group B Streptococci are able to respire in the presence of heme, enhancing resistance to oxidative stress and improving their survival98. Our results suggest that the UROS gene may modulate the presence of Streptococcus spp. making these animals more susceptible to Streptococci colonization. A total of three candidate genes were identified in the SSC15 region (25.15–27.87 Mb): ERCC3 (ERCC excision repair 3, TFIIH core complex helicase subunit), BIN1 (bridging integrator 1), and MAP3K2 (mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 2). The ERCC3 gene expression was downregulated in human gastric cells after the infection with Helicobacter pylori99. In the same direction as the aforementioned GALNT15 gene, the BIN1 gene might modulate the abundance of mucin dweller bacteria like Streptococcus spp. because of the attenuation of BIN1 favours the intestinal barrier function100. The protein encoded by the last candidate gene of this SSC15 region, MAP3K2, activates the toll like receptor 9 (TLR9) that recognizes CpG oligodeoxynucleotide motif in bacteria101. Finally, the last significant region (45.25 Mb) in SSC18 contained one microRNA, ssc-mir-196b-1, that was found upregulated in the duodenum of piglets that were resistant to Escherichia coli infection102.

Conclusion

This report identifies associations between the pig genome and the relative abundance of six genera (Akkermansia, CF231, Phascolarctobacterium, Prevotella, SMB53 and Streptococcus). Most of the candidate genes found in the 17 associated regions of the pig genome encode for proteins that are involved in the host defence system, including the immune system, physical barriers such as the mucin layer or cell junctions, whereas other proteins participate in the metabolism of mucopolysaccharides or bile acids. Our results confirm the importance of host genomics in the modulation of the microbiota composition. However, the associations found in this study could be specific of our population, as the associated polymorphisms found may not be segregating in other populations and the gut microbiota is affected by different factors such as breed, age and diet. Therefore, further studies are warranted in different populations to determine which genetic combinations favour the enrichment of beneficial bacteria, providing the individual with the best intestinal health to avoid the entrance of potential pathogens.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) and the Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (MINECO AGL2014-56369-C2 and AGL2017-82641-R). D. Crespo-Piazuelo was funded by a “Formació i Contractació de Personal Investigador Novell” (FI-DGR) Ph.D grant from the Generalitat de Catalunya (ECO/1788/2014) and by the PiGutNet COST Action (www.pigutnet.eu) for a Short Term Scientific Mission at the GABI laboratory (INRA, France) under the supervision of J. Estellé. Contract of L. Migura-Garcia was supported by INIA and the European Social Fund. L. Criado-Mesas was funded with a FPI grant from the AGL2014-56369-C2 project. M. Revilla was also funded by a FI-DGR (ECO/1639/2013). M. Ballester was financially supported by a “Ramón y Cajal” contract (RYC-2013-12573) from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness. We acknowledge the support of the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness for the “Severo Ochoa Programme for Centres of Excellence in R&D” 2016-2019 (SEV-2015-0533) grant awarded to the Centre for Research in Agricultural Genomics and the CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya. The authors would like to thank the Mazafra S. L. slaughterhouse for providing access to the data and material used in this study and, specially, to Francisco Minero for the skilful veterinary assistance. We also acknowledge the contribution of Rita Benítez in the collection of samples and microbial DNA extractions.

Author Contributions

J.M.F. and A.I.F. conceived and designed the experiments; J.M.F. was the principal investigator of the project; this work is part of the PhD thesis of D.C.P. co-supervised by M.B. and J.M.F.; J.M.G.C. provided animal samples; D.C.P., M.R., M.M., J.M.G.C. and A.I.F. collected samples; D.C.P. and M.B. tested the DNA extraction protocol; D.C.P. and M.M. performed the microbial DNA extraction; L.C.M. performed the pig genomic DNA extraction; AC genotyped the samples; D.C.P. and J.E. analysed the data; D.C.P., L.M.G., M.B. and J.M.F. wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The raw sequencing data generated by this study were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under BioProject accession number PRJNA540380.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-45066-6.

References

- 1.Nicholson JK, et al. Host-gut microbiota metabolic interactions. Science. 2012;336:1262–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1223813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caballero S, Pamer EG. Microbiota-mediated inflammation and antimicrobial defense in the intestine. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2015;33:227–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lederberg J, McCray A. ‘Ome Sweet’ Omics—a genealogical treasury of words. Scientist. 2001;15:8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamada N, Seo S-U, Chen GY, Núñez G. Role of the gut microbiota in immunity and inflammatory disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013;13:321–335. doi: 10.1038/nri3430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costello EK, Stagaman K, Dethlefsen L, Bohannan BJM, Relman DA. The application of ecological theory toward an understanding of the human microbiome. Science. 2012;336:1255–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1224203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johansson MEV, et al. Composition and functional role of the mucus layers in the intestine. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2011;68:3635–41. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0822-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johansson MEV, Larsson JMH, Hansson GC. The two mucus layers of colon are organized by the MUC2 mucin, whereas the outer layer is a legislator of host-microbial interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108(Suppl):4659–65. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006451107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hooper LV, Stappenbeck TS, Hong CV, Gordon JI. Angiogenins: a new class of microbicidal proteins involved in innate immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:269–73. doi: 10.1038/ni888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu H, Mazmanian SK. Innate immune recognition of the microbiota promotes host-microbial symbiosis. Nat. Immunol. 2013;14:668–675. doi: 10.1038/ni.2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Human Microbiome Project Consortium. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature486, 207–14 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Xiao L, et al. A reference gene catalogue of the pig gut microbiome. Nat. Microbiol. 2016;1:16161. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang M, Donovan SM. Human microbiota-associated swine: current progress and future opportunities. ILAR J. 2015;56:63–73. doi: 10.1093/ilar/ilv006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Estellé, J. et al. The influence of host’s genetics on the gut microbiota composition in pigs and its links with immunity traits. in 10th World Congress of Genetics Applied to Livestock Production, Vancouver,BC, Canada Available at: https://www.asas.org/docs/default-source/wcgalp-proceedings-oral/358_paper_9784_manuscript_952_0.pdf (2014).

- 14.Camarinha-Silva A, et al. Host Genome Influence on Gut Microbial Composition and Microbial Prediction of Complex Traits in Pigs. Genetics. 2017;206:1637–1644. doi: 10.1534/genetics.117.200782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turpin W, et al. Association of host genome with intestinal microbial composition in a large healthy cohort. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:1413–1417. doi: 10.1038/ng.3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodrich JK, Davenport ER, Clark AG, Ley RE. The Relationship Between the Human Genome and Microbiome Comes into View. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2017;51:413–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blekhman R, et al. Host genetic variation impacts microbiome composition across human body sites. Genome Biol. 2015;16:191. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0759-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodrich JK, Davenport ER, Waters JL, Clark AG, Ley RE. Cross-species comparisons of host genetic associations with the microbiome. Science. 2016;352:532–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spor A, Koren O, Ley R. Unravelling the effects of the environment and host genotype on the gut microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011;9:279–90. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Estellé, J. et al. Host genetics influences gut microbiota composition in pigs. in 36th International Society for Animal Genetics Conference, Dublin, Ireland, Available at: https://www.isag.us/2017/docs/ISAG2017_Proceedings.pdf (2017).

- 21.Caporaso JG, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:335–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rideout JR, et al. Subsampled open-reference clustering creates consistent, comprehensive OTU definitions and scales to billions of sequences. PeerJ. 2014;2:e545. doi: 10.7717/peerj.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bokulich NA, et al. Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:57–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–10. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeSantis TZ, et al. Greengenes, a Chimera-Checked 16S rRNA Gene Database and Workbench Compatible with ARB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:5069–5072. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03006-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. Phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oksanen, J. et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. (2016).

- 28.Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. (Springer-Verlag New York, 2009).

- 29.Bray JR, Curtis JT. An Ordination of the Upland Forest Communities of Southern Wisconsin. Ecol. Monogr. 1957;27:325–349. doi: 10.2307/1942268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E. F. & Maniatis, T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. In E3–E4 (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1989).

- 31.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:559–75. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou X, Stephens M. Genome-wide efficient mixed-model analysis for association studies. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:821–4. doi: 10.1038/ng.2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple. Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kinsella RJ, et al. Ensembl BioMarts: a hub for data retrieval across taxonomic space. Database (Oxford). 2011;2011:bar030. doi: 10.1093/database/bar030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLaren W, et al. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP Effect Predictor. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2069–2070. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramayo-Caldas Y, et al. Phylogenetic network analysis applied to pig gut microbiota identifies an ecosystem structure linked with growth traits. ISME J. 2016;10:2973–2977. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holman DB, Brunelle BW, Trachsel J, Allen HK. Meta-analysis To Define a Core Microbiota in the Swine Gut. mSystems. 2017;2:e00004–17. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00004-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao W, et al. The dynamic distribution of porcine microbiota across different ages and gastrointestinal tract segments. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molinero LL, Cubre A, Mora-Solano C, Wang Y, Alegre M-L. T cell receptor/CARMA1/NF-κB signaling controls T-helper (Th) 17 differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:18529–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204557109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hiraoka N, et al. Molecular cloning and expression of two distinct human chondroitin 4-O-sulfotransferases that belong to the HNK-1 sulfotransferase gene family. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:20188–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002443200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ouwerkerk JP, de Vos WM, Belzer C. Glycobiome: bacteria and mucus at the epithelial interface. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2013;27:25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ottman N, Geerlings SY, Aalvink S, de Vos WM, Belzer C. Action and function of Akkermansia muciniphila in microbiome ecology, health and disease. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2017;31:637–642. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Everard A, et al. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:9066–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219451110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leber A, et al. Bistability analyses of CD4+ T follicular helper and regulatory cells during Helicobacter pylori infection. J. Theor. Biol. 2016;398:74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2016.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhernakova A, et al. Population-based metagenomics analysis reveals markers for gut microbiome composition and diversity. Science. 2016;352:565–9. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Briolat J, et al. New antimicrobial activity for the catecholamine release-inhibitory peptide from chromogranin A. C. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005;62:377–385. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4461-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dall E, Brandstetter H. Structure and function of legumain in health and disease. Biochimie. 2016;122:126–50. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gururajan M, et al. MicroRNA 125b inhibition of B cell differentiation in germinal centers. Int. Immunol. 2010;22:583–92. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxq042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Negi V, et al. Altered expression and editing of miRNA-100 regulates iTreg differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:8057–65. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmidt V, Subkhangulova A, Willnow TE. Sorting receptor SORLA: cellular mechanisms and implications for disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017;74:1475–1483. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2410-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Terai K, et al. Levels of soluble LR11/SorLA are highly increased in the bile of patients with biliary tract and pancreatic cancers. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2016;457:130–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hojyo S, et al. Zinc transporter SLC39A10/ZIP10 controls humoral immunity by modulating B-cell receptor signal strength. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:11786–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323557111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Derrien M, et al. Modulation of Mucosal Immune Response, Tolerance, and Proliferation in Mice Colonized by the Mucin-Degrader Akkermansia muciniphila. Front. Microbiol. 2011;2:166. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yabas M, et al. ATP11C is critical for the internalization of phosphatidylserine and differentiation of B lymphocytes. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:441–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Siggs OM, Schnabl B, Webb B, Beutler B. X-linked cholestasis in mouse due to mutations of the P4-ATPase ATP11C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:7890–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104631108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Islam KBMS, et al. Bile acid is a host factor that regulates the composition of the cecal microbiota in rats. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1773–81. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Khan TJ, et al. Effect of atorvastatin on the gut microbiota of high fat diet-induced hypercholesterolemic rats. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:662. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-19013-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Song X, et al. Growth Factor FGF2 Cooperates with Interleukin-17 to Repair Intestinal Epithelial Damage. Immunity. 2015;43:488–501. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu F, et al. Phascolarctobacterium faecium abundant colonization in human gastrointestinal tract. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017;14:3122–3126. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.4878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang Q, et al. Inulin-type fructan improves diabetic phenotype and gut microbiota profiles in rats. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4446. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shin D, Howng SYB, Ptáček LJ, Fu Y-H. miR-32 and its target SLC45A3 regulate the lipid metabolism of oligodendrocytes and myelin. Neuroscience. 2012;213:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.03.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang Y, et al. Lysosome-associated small Rab GTPase Rab7b negatively regulates TLR4 signaling in macrophages by promoting lysosomal degradation of TLR4. Blood. 2007;110:962–71. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-066027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Spanò S, Liu X, Galán JE. Proteolytic targeting of Rab29 by an effector protein distinguishes the intracellular compartments of human-adapted and broad-host Salmonella. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:18418–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111959108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Qiu B, et al. NUCKS is a positive transcriptional regulator of insulin signaling. Cell Rep. 2014;7:1876–86. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang J, et al. IκB Kinase ε Is an NFATc1 Kinase that Inhibits T Cell Immune Response. Cell Rep. 2016;16:405–418. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ehlting C, et al. MAPKAP kinase 2 regulates IL-10 expression and prevents formation of intrahepatic myeloid cell aggregates during cytomegalovirus infections. J. Hepatol. 2016;64:380–389. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.De Filippo C, et al. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:14691–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005963107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang X, et al. Cytokine-like 1 Chemoattracts Monocytes/Macrophages via CCR2. J. Immunol. 2016;196:4090–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bonnycastle LL, et al. Autosomal dominant diabetes arising from a Wolfram syndrome 1 mutation. Diabetes. 2013;62:3943–50. doi: 10.2337/db13-0571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ussar S, et al. Regulation of Glucose Uptake and Enteroendocrine Function by the Intestinal Epithelial Insulin Receptor. Diabetes. 2017;66:886–896. doi: 10.2337/db15-1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Murri M, et al. Gut microbiota in children with type 1 diabetes differs from that in healthy children: a case-control study. BMC Med. 2013;11:46. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Venkatesan M, Kuntz DA, Rose DR. Human lysosomal alpha-mannosidases exhibit different inhibition and metal binding properties. Protein Sci. 2009;18:2242–51. doi: 10.1002/pro.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Koropatkin NM, Cameron EA, Martens EC. How glycan metabolism shapes the human gut microbiota. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;10:323–35. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pajarillo EAB, Chae JP, Kim HB, Kim IH, Kang D-K. Barcoded pyrosequencing-based metagenomic analysis of the faecal microbiome of three purebred pig lines after cohabitation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015;99:5647–56. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Guo Y, Zhu N, Zhu S, Deng C. Molecular phylogenetic diversity of bacteria and its spatial distribution in composts. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007;103:1344–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kumar V, Ali A. Targeting calpains: A novel immunomodulatory approach for microbial infections. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2017;814:28–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Autheman D, et al. Clostridium perfringens beta-toxin induces necrostatin-inhibitable, calpain-dependent necrosis in primary porcine endothelial cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64644. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Holmquist E, Okroj M, Nodin B, Jirström K, Blom AM. Sushi domain-containing protein 4 (SUSD4) inhibits complement by disrupting the formation of the classical C3 convertase. FASEB J. 2013;27:2355–66. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-222042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yang C-W, et al. Regulation of T Cell Receptor Signaling by DENND1B in TH2 Cells and Allergic Disease. Cell. 2016;164:141–155. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hermiston ML, Xu Z, Weiss A. CD45: a critical regulator of signaling thresholds in immune cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2003;21:107–37. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.140946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Henao-Mejia J, et al. The microRNA miR-181 is a critical cellular metabolic rheostat essential for NKT cell ontogenesis and lymphocyte development and homeostasis. Immunity. 2013;38:984–97. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li T, Chiang JYL. Bile acids as metabolic regulators. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2015;31:159–65. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wüst PK, Horn MA, Drake HL. Clostridiaceae and Enterobacteriaceae as active fermenters in earthworm gut content. ISME J. 2011;5:92–106. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Horie M, et al. Comparative analysis of the intestinal flora in type 2 diabetes and nondiabetic mice. Exp. Anim. 2017;66:405–416. doi: 10.1538/expanim.17-0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kozu Y, et al. Protocadherin-1 is a glucocorticoid-responsive critical regulator of airway epithelial barrier function. BMC Pulm. Med. 2015;15:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12890-015-0078-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xu H, Sobue T, Bertolini M, Thompson A, Dongari-Bagtzoglou A. Streptococcus oralis and Candida albicans Synergistically Activate μ-Calpain to Degrade E-cadherin From Oral Epithelial Junctions. J. Infect. Dis. 2016;214:925–34. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Takenaka K, et al. Role of phospholipase C-L2, a novel phospholipase C-like protein that lacks lipase activity, in B-cell receptor signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:7329–38. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.20.7329-7338.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Clausen H, Bennett EP. A family of UDP-GalNAc: polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyl-transferases control the initiation of mucin-type O-linked glycosylation. Glycobiology. 1996;6:635–46. doi: 10.1093/glycob/6.6.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Homer KA, Patel R, Beighton D. Effects of N-acetylglucosamine on carbohydrate fermentation by Streptococcus mutans NCTC 10449 and Streptococcus sobrinus SL-1. Infect. Immun. 1993;61:295–302. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.1.295-302.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Saeki K, Miura Y, Aki D, Kurosaki T, Yoshimura A. The B cell-specific major raft protein, Raftlin, is necessary for the integrity of lipid raft and BCR signal transduction. EMBO J. 2003;22:3015–26. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Alonso MA, Millán J. The role of lipid rafts in signalling and membrane trafficking in T lymphocytes. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:3957–65. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.22.3957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Triantafilou M, Miyake K, Golenbock DT, Triantafilou K. Mediators of innate immune recognition of bacteria concentrate in lipid rafts and facilitate lipopolysaccharide-induced cell activation. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:2603–11. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.12.2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Toledo A, Benach JL. Hijacking and Use of Host Lipids by Intracellular Pathogens. Microbiol. Spectr. 2015;3:637–666. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.VMBF-0001-2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Huang X, et al. Genome-wide association studies identify susceptibility loci affecting respiratory disease in Chinese Erhualian pigs under natural conditions. Anim. Genet. 2017;48:30–37. doi: 10.1111/age.12504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tsai SF, Bishop DF, Desnick RJ. Human uroporphyrinogen III synthase: molecular cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of a full-length cDNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:7049–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.19.7049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Eichenbaum Z, Muller E, Morse SA, Scott JR. Acquisition of iron from host proteins by the group A streptococcus. Infect. Immun. 1996;64:5428–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5428-5429.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wan Y, Zhang S, Li L, Chen H, Zhou R. Characterization of a novel streptococcal heme-binding protein SntA and its interaction with host antioxidant protein AOP2. Microb. Pathog. 2017;111:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Franza T, et al. A partial metabolic pathway enables group b streptococcus to overcome quinone deficiency in a host bacterial community. Mol. Microbiol. 2016;102:81–91. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chiou CC, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection induced alteration of gene expression in human gastric cells. Gut. 2001;48:598–604. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.5.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chang MY, et al. Bin1 attenuation suppresses experimental colitis by enforcing intestinal barrier function. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2012;57:1813–21. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2147-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wen M, et al. Stk38 protein kinase preferentially inhibits TLR9-activated inflammatory responses by promoting MEKK2 ubiquitination in macrophages. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7167. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wu Z, et al. Identification of microRNAs regulating Escherichia coli F18 infection in Meishan weaned piglets. Biol. Direct. 2016;11:59. doi: 10.1186/s13062-016-0160-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw sequencing data generated by this study were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under BioProject accession number PRJNA540380.