Abstract

This randomized clinical trial evaluates the postoperative drug-disposal practices of adults provided with a drug-deactivation bag in comparison with those who received usual care or a disposal information sheet.

Opioids are commonly prescribed for acute pain, yet most pills remain unused and undisposed.1 Current disposal options are limited to US Drug Enforcement Administration–authorized opioid collectors, including law enforcement agencies, pharmacies, and organized pill-drop events; however, many patients remain unaware of them.2,3 We examined the effect of an activated charcoal bag that allows for in-home opioid disposal on the probability of disposal after a surgical procedure, compared with usual care or educational materials detailing disposal resources.

Methods

This randomized clinical trial was approved by the Michigan Medicine Institutional Review Board and registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03179566). No changes were made to the trial design after registration. The trial protocol is available in Supplement 1. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Opioid-naive patients 18 years or older undergoing an outpatient surgical procedure at Michigan Medicine were recruited. Non-English speakers and patients unable to complete the survey were excluded. Participants were randomized to 1 of 3 arms: (1) usual care, (2) educational pamphlet with detailed instructions for locating Drug Enforcement Administration–registered disposal locations (http://michigan-open.org/prescription-medication-disposal-brochure/), or (3) activated charcoal bag for opioid deactivation (Deterra Drug Deactivation System; Verde Technologies). Usual care was implemented in the first 2 weeks, and the intervention groups were randomized through a block randomization schedule for each day to follow. Participants and surgeons were blinded, and the intervention or usual care was presented perioperatively by the nurse. We contacted participants by phone or email 4 to 6 weeks after their surgical procedure to inquire about their postoperative opioid use and disposal of unused medications. In pilot work, we observed a 21% rate of self-reported disposal at our institution. Assuming a 50% increase in disposal rate owing to the charcoal bag intervention, we estimated 65 patients per group, assuming an α = .0125 to account for multiple comparisons and a beta of 80%.

Tests of association were performed between study arm and each covariate. χ2 Tests were used to examine all categorical covariates except for the disposal method, which was examined using Fisher exact test owing to the sample size. Analysis of variance test was used to examine age. All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

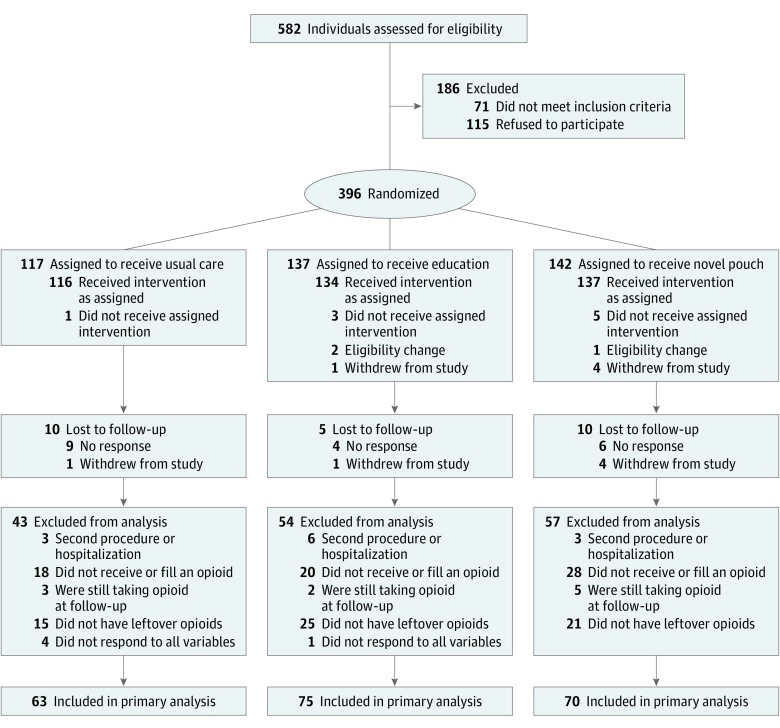

Between June 6, 2017, and July 21, 2017, we recruited 396 participants. We excluded participants who did not receive or fill an opioid prescription, who were readmitted or underwent a procedure during the follow-up period, who did not have leftover opioids, who were lost to follow-up, and who had incomplete data. In total, 208 participants remained for the primary analysis (Figure).

Figure. Participant Flow Diagram.

Of the 582 patients approached, 71 (8.2%) did not meet eligibility criteria and 115 (22.5%) refused to participate. Of those enrolled and randomized, 359 participants (90.7%) received the intervention. The a priori analysis plan was to include only those participants who filled an opioid prescription and also stopped taking opioids at the follow-up time point with pills remaining. After the noted exclusions, 208 participants were included in the primary analysis.

We observed that 18 patients (28.6%) who received usual care reported disposing opioids, compared with 25 patients (33.3%) who received education regarding disposal locations and 40 patients (57.1%) who received a charcoal activated bag. After adjusting for preoperative patient characteristics (which were well matched across the 3 arms; Table), we found the odds of opioid disposal were 3.8 (95% CI, 1.7-8.5) times higher among participants who received a charcoal bag compared with those who received usual care. Participants who received a charcoal bag reported less medication flushing (2 [5.0%]) or inappropriate garbage disposal (2 [5.0%]) and were statistically significantly less likely to leave the home for disposal (1 [2.5%]), when compared with participants in the other 2 groups (Table).

Table. Participant Characteristics and Outcomes by Group.

| Postoperative Opioid Disposal | No. (%) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual Care | Educational Pamphlet | Activated Charcoal Bag | ||

| No. | 63 | 75 | 70 | |

| Self-reported opioid disposal 4-6 wk after surgical procedure | 18 (28.6) | 25 (33.3) | 40 (57.1) | .001 |

| Preoperative characteristics | ||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 46.92 (14.91) | 46.00 (15.22) | 45.10 (15.13) | .79 |

| Female sex | 40 (63.5) | 54 (72.0) | 45 (64.3) | .49 |

| White race/ethnicity | 52 (82.5) | 70 (93.3) | 61 (87.1) | .15 |

| Surgical service | ||||

| Gynecology | 4 (6.4) | 8 (10.7) | 9 (12.9) | .44 |

| Plastic | 13 (20.6) | 14 (18.7) | 10 (14.3) | |

| Orthopedic | 22 (34.9) | 28 (37.3) | 24 (34.2) | |

| Oncology | 7 (11.1) | 12 (16.0) | 11 (15.7) | |

| Otolaryngology | 8 (12.7) | 8 (10.7) | 3 (4.3) | |

| Other | 9 (14.3) | 5 (6.7) | 13 (18.6) | |

| Insurance type | ||||

| Private only | 45 (71.4) | 56 (74.7) | 48 (68.6) | .86 |

| Medicaid or Medicare only | 9 (14.3) | 7 (9.3) | 10 (14.3) | |

| Other | 9 (14.3) | 12 (16.0) | 12 (17.1) | |

| Disposal method | ||||

| No. | 18 | 25 | 40 | <.001 |

| In home | ||||

| Garbage | 2 (11.1) | 1 (4.0) | 0 | |

| Garbage after mixing with unpalatable substance | 2 (11.1) | 5 (20.0) | 2 (5.0) | |

| Activated charcoal bag | 0 | 0 | 35 (87.5) | |

| Flushed down the toilet | 3 (16.7) | 5 (20.0) | 2 (5.0) | |

| Out of home | ||||

| Law enforcement | 5 (27.8) | 5 (20.0) | 0 | |

| Authorized pharmacy or hospital | 4 (22.2) | 6 (24.0) | 1 (2.5) | |

| Take-back drive | 0 | 1 (4.0) | 0 | |

| Othera | 2 (11.1) | 2 (8.0) | 0 | |

Including “I don't know” (n = 3) and “Pharmacy gave me bag to mix with and throw away” (n = 1).

Discussion

Receiving an activated charcoal bag for in-home disposal of unused opioids was associated with an adjusted 3.8-fold increase in self-reported disposal among adults who underwent elective surgical procedure, compared with receiving usual care. After the operation, roughly 70% of opioids remain unused, and these unused pills are the primary source of diversion for nonmedical use.4,5 Moreover, the proportion of prescribed opioids associated with surgical procedure is increasing, compared with other episodes of care.5 Although numerous policies have been enacted to slow opioid-associated morbidity and mortality, few have examined pragmatic strategies to promote safe disposal.

Our findings suggest that simple, low-cost interventions (US $2.59-$6.99/bag), such as in-home deactivation methods, could reduce the number of unused opioids available for diversion. Although flushing medications is a disposal option suggested by the US Food and Drug Administration, it is not preferred and is intended only for those without other options. The US Environmental Protection Agency and the Canadian government also discourage flushing, emphasizing the risk of medication contamination in drinking water. For example, in 2017, the Puget Sound Mussel Monitoring Program found detectable levels of oxycodone hydrochloride in bay mussels in Seattle, Washington, underscoring the negative effect of unsafe disposal practices. Although this study represents data from outpatient surgical procedures at a single academic center, it highlights the importance of providing accessible disposal methods to reduce the flow of excess opioids into communities.

Trial Protocol

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Bicket MC, Long JJ, Pronovost PJ, Alexander GC, Wu CL. Prescription Opioid Analgesics Commonly Unused After Surgery: A Systematic Review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(11):1066-1071. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reddy A, de la Cruz M, Rodriguez EM, et al. Patterns of storage, use, and disposal of opioids among cancer outpatients. Oncologist. 2014;19(7):780-785. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kennedy-Hendricks A, Gielen A, McDonald E, McGinty EE, Shields W, Barry CL. Medication Sharing, Storage, and Disposal Practices for Opioid Medications Among US Adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):1027-1029. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill MV, McMahon ML, Stucke RS, Barth RJ Jr. Wide Variation and Excessive Dosage of Opioid Prescriptions for Common General Surgical Procedures. Ann Surg. 2017;265(4):709-714.doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCabe SE, West BT, Boyd CJ. Leftover prescription opioids and nonmedical use among high school seniors: a multi-cohort national study. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(4):480-485. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Data Sharing Statement