Abstract

This observational study of Medicare fee-for-service claims data evaluates demographic characteristics of psychiatrists who deliver telemental health visits in the Medicare population.

Individuals in many regions of the United States experience inadequate availability of specialty mental health care.1 Telemental health, the use of video visits between a patient and a remote mental health specialist, may address these access barriers. Telemental health has grown rapidly but unevenly across the nation.2 Little is known about the characteristics of psychiatrists associated with the use of this technology. Research has examined characteristics of physicians who adopt other technologies such as electronic health records and diagnostic or therapeutic procedures; in general, such physicians are younger, male, US medical school graduates, and work in larger practices.3,4 Among psychiatrists who care for Medicare beneficiaries, we compared the characteristics of psychiatrists who do and do not use telemental health.

Methods

Using a 20% random sample of 2014-2016 Medicare fee-for-service claims, we identified 28 567 psychiatrists who billed for 1 or more evaluation and management or outpatient consultation codes: 99201-99499, 96150-4, 90832-4, 90836-8, 96116, 90839-90840, 90845-7, 90791-2, 90785, G0425-G0427, G0459, G0406-8, and G0442. Given the 20% sample, the number of visit estimates was multiplied by 5. Using practice zip code, we categorized the practice location with US Department of Agriculture rural-urban commuting area codes and, using tax identifier, we categorized practices by their size and composition. The Harvard Medical School institutional review board approved the study and granted a waiver of informed consent.

Telemental health psychiatrists were those with at least 1 visit with a telehealth modifier code GT/GQ or telemedicine-specific visit (G0425-G0427). High-use psychiatrists were those with more than 100 telemental health visits. Using national practitioner identifiers, we linked these data to Doximity data to determine sex, years of practice, medical school type, and publication of a peer-reviewed publication (as a marker of an academic physician). Doximity is a comprehensive physician database that is built using self-report, public data, and data from collaborating medical schools.5 Controlling for state of practice, we used multivariable logistic regression to identify physician characteristics associated with use of telemental health. We used multiple imputation to address missing values.

Results

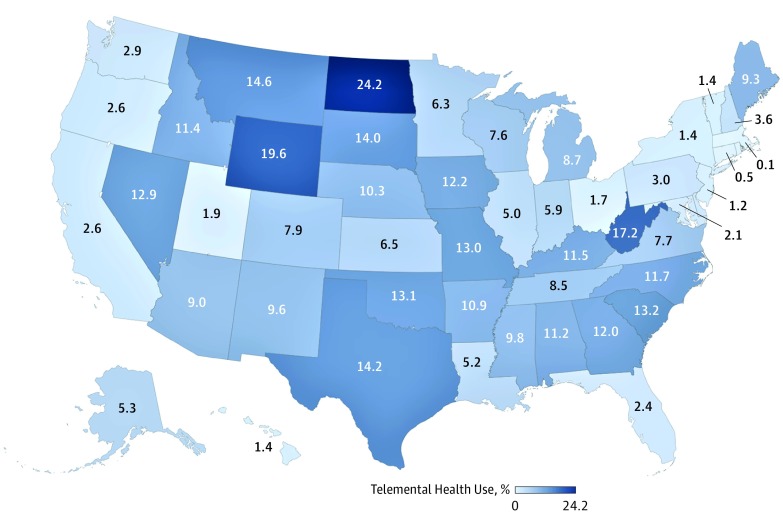

Among the 28 567 psychiatrists who provided care during this period, 1544 (5.4%) delivered 377 440 telemental health visits. Of the psychiatrists who provided telemental health visits, 622 (40.2%) provided 100 or more such visits. Among all psychiatrists in a state, the fraction providing telemental health was highest in North Dakota (24.2%) and Wyoming (19.6%) and lowest in Massachusetts (0.1%) (Figure).

Figure. Percentage of Psychiatrists in State Who Have Provided 1 or More Telemental Health Visits, 2014-2016.

Compared with psychiatrists who did not use telemental health (n = 27 023), psychiatrists who did (n = 1544) were in practice for less time since medical school (0-19 years of experience: 26.9% [415] vs 22.8% [6163]; 20-30 years of experience: 29.9% [461] vs 23.1% [6241]; 31-40 years of experience: 21.5% [332] vs 23.7% [641]; and >41 years of experience: 12.8% [197] vs 22.4%, 6048]; P < .001), were less likely to have peer-reviewed publications (21.2% [328] vs 25.0% [6790]; P < .001), were less likely to be in solo practice (9.1% [141] vs 23.6% [6377]; P < .001); and were more likely to practice in rural locations (24.0% [374] vs 6.0% 1608]; P < .001) (Table). Though psychiatrists in solo practice were less likely to use telemental health, there was no consistent association between size or composition of practice and telemental health use. These differences were consistent with the multivariate regression.

Table. Characteristics of Psychiatrists Who Have and Have Not Delivered Telemental Health Visits.

| Physician Characteristics | Psychiatrists, No. (%) | P Value | OR (95% CI)a | Psychiatrists, No. (%) | P Value | OR (95% CI)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provided ≥1 Telemental Health Visits (n = 1544) | Provided No Telemental Health Visits (n = 27 023) | Provided ≥100 Telemental Health Visits (n = 622) | Provided No Telemental Health Visits (n = 27 023) | |||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 943 (61.1) | 16 800 (62.2) | .39 | 1 [Reference] | 379 (60.9) | 16 800 (62.2) | .53 | 1 [Reference] |

| Female | 601 (38.9) | 10 220 (37.8) | 0.99 (0.87-1.12) | 243 (39.1) | 10 220 (37.8) | 1.06 (0.94-1.21) | ||

| Years of experienceb | ||||||||

| 0-19 | 415 (26.9) | 6163 (22.8) | <.001 | 1.67 (1.28-2.17) | 19 (3.1) | 6163 (22.8) | <.001 | 1.42 (1.05-1.92) |

| 20-30 | 461 (29.9) | 6241 (23.1) | 1.75 (1.39-2.20) | 71 (11.4) | 6241 (23.1) | 1.57 (1.16-2.12) | ||

| 31-40 | 332 (21.5) | 6401 (23.7) | 1.44 (1.19-1.73) | 162 (26.0) | 6401 (23.7) | 1.13 (0.90-1.43) | ||

| ≥41 | 197 (12.8) | 6048 (22.4) | 1 [Reference] | 315 (50.6) | 6048 (22.4) | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Missingc | 139 (9.0) | 2170 (8.0) | NA d | 55 (8.8) | 2170 (8.0) | NA d | ||

| Location of practice | ||||||||

| Urban | 1169 (76.0) | 25 171 (93.1) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | 431 (69.3) | 25 171 (93.1) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] |

| Rural | 374 (24.0) | 1608 (6.0) | 3.56 (2.61-4.26) | 191 (30.7) | 1608 (6.0) | 4.90 (3.31-7.53) | ||

| Missingc | 1 (0.) | 244 (0.9) | NAd | 0 (0.0) | 244 (0.9) | NAd | ||

| Any peer-reviewed publications | ||||||||

| No | 1216 (78.8) | 20 233 (74.9) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | 499 (80.2) | 20 233 (74.9) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 328 (21.2) | 6790 (25.0) | 0.92 (0.79-1.07) | 123 (19.8) | 6790 (25.0) | 0.90 (0.70-1.71) | ||

| US vs foreign medical school | ||||||||

| US | 862 (55.8) | 11 515 (57.4) | .61 | 1 [Reference] | 341 (54.8) | 11 515 (57.4) | .36 | 1 [Reference] |

| Foreign medical grad | 439 (28.4) | 7660 (28.3) | 1.20 (0.99-1.46) | 192 (30.9) | 7660 (28.3) | 1.25 (0.92-1.71) | ||

| Missingc | 243 (15.7) | 3855 (14.3) | NAd | 89 (14.3) | 3855 (14.3) | NAd | ||

| Practice sized | ||||||||

| Solo practitioner | 141 (9.1) | 6377 (23.6) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] | 66 (10.6) | 6377 (23.6) | <.001 | 1 [Reference] |

| Small practice (2-9) | ||||||||

| Less than half psychiatrists (≤50) | 114 (7.4) | 1489 (5.5) | 2.47 (1.89-3.22) | 56 (9.0) | 1489 (5.5) | 2.60 (1.63-4.14) | ||

| Primarily psychiatrists (>50) | 92 (6.0) | 1299 (4.8) | 2.42 (1.69-3.51) | 41 (6.6) | 1299 (4.8) | 2.42 (1.22-4.81) | ||

| Larger practice (10-49) | ||||||||

| Less than half psychiatrists (≤50) | 366 (23.7) | 3574 (13.2) | 3.57 (2.64-4.83) | 157 (25.2) | 3574 (13.2) | 3.19 (1.99-5.10) | ||

| Primarily psychiatrists (>50) | 211 (13.7) | 2400 (8.9) | 3.41 (1.71-6.82) | 104 (16.7) | 2400 (8.9) | 3.61 (1.46-8.91) | ||

| Very large practice (≥50) | 620 (40.2) | 11 884 (43.8) | 1.92 (1.46-2.52) | 198 (1.6) | 11 884 (98.4) | 1.31 (0.86-1.20) | ||

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable, OR, odds ratio; US, United States.

Results from multivariate regression model with characteristics shown in table also control for state of practice. Missing values not shown for regression given imputation was used in regression for missing values.

Years of experience estimated by subtracting years of graduation from medical school by 2018.

Missing values shown in unadjusted analyses only. In multivariate models we used multiple imputation with 10 iterations.

Practice size is the number of providers (as captured by unique national practitioner identifiers) in the same practice (practices captured by tax identifier).

Discussion

The variation across states in the fraction of psychiatrists providing telemental health is notable. In some states, less than 1% of psychiatrists provide telemental health visits, while in other states approximately 20% provide telemental health visits. This variation might be driven by needs of the local community and state laws and regulations governing reimbursement of telemedicine and licensure.

Our analysis is limited to psychiatrists who provide care in the Medicare fee-for-service program and may not be a representative sample of all psychiatrists.6

Consistent with characteristics of physicians who adopt other technological innovations, those who provide telemental health tend to be younger. However, we did not find an association between uptake and physician sex, location of medical school, or type of practice. One notable predictor associated with use of telemental health visits was practicing in a rural community. Possibly these psychiatrists are more aware of geographic access barriers and therefore apt to adopt this technology.

References:

- 1.Thomas KC, Ellis AR, Konrad TR, Holzer CE, Morrissey JP. County-level estimates of mental health professional shortage in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(10):1323-1328. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.10.1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, Souza J, et al. . Rapid growth in mental health telemedicine use among rural Medicare beneficiaries, wide variation across states. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(5):909-917. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burt CW, Sisk JE. Which physicians and practices are using electronic medical records? Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(5):1334-1343. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.5.1334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freiman MP. The rate of adoption of new procedures among physicians: the impact of specialty and practice characteristics. Med Care. 1985;23(8):939-945. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198508000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jena AB, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in physician salary in us public medical schools. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1294-1304. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, Pincus HA. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):176-181. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]