Abstract

Aim:

This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of different bacterial species affecting ducks as well as demonstrating the antimicrobial susceptibility and molecular typing of the isolated strains.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 500 samples were randomly collected from different duck farms at Ismailia Governorate, Egypt. The collected samples were subjected to the bacteriological examination. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was applied for amplification of Kmt1 gene of Pasteurella multocida and X region of protein-A (spA) gene of the isolated Staphylococcus aureus strains to ensure their virulence. The antibiotic sensitivity test was carried out.

Results:

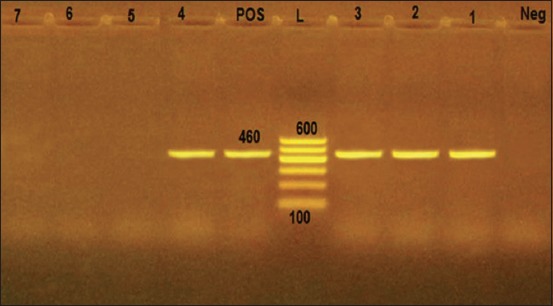

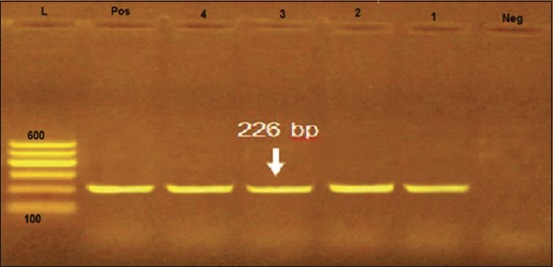

The most common pathogens isolated from apparently healthy and diseased ducks were P. multocida (10.4% and 25.2%), Escherichia coli (3.6% and 22.8%), Staphylococcus epidermidis (10% and 8.8%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (2% and 10%), and Proteus vulgaris (0.8% and 10%), respectively. In addition, S. aureus and Salmonella spp. were isolated only from the diseased ducks with prevalence (12.2%) and (2.8%), respectively. Serotyping of the isolated E. coli strains revealed that 25 E. coli strains were belonged to five different serovars O1, O18, O111, O78, and O26, whereas three strains were untypable. Salmonella serotyping showed that all the isolated strains were Salmonella Typhimurium. PCR revealed that four tested P. multocida strains were positive for Kmt1 gene with specific amplicon size 460 bp, while three strains were negative. In addition, all the tested S. aureus strains were positive for spA gene with specific amplicon size 226 bp. The antibiotic sensitivity test revealed that most of the isolated strains were sensitive to enrofloxacin, norfloxacin, and ciprofloxacin.

Conclusion:

P. multocida is the most predominant microorganism isolated from apparently healthy and diseased ducks followed by E. coli and Staphylococci. The combination of both phenotypic and genotypic characterization is more reliable an epidemiological tool for identification of bacterial pathogens affecting ducks.

Keywords: Antibiotic sensitivity, duck, Escherichia coli, Pasteurella multocida, polymerase chain reaction, Staphylococci

Introduction

Virulent bacteria are incriminated in huge economic casualties in the duck industry globally. Bacterial diseases cause higher mortality rates in ducks more than viral diseases. The mortality rates and bacterial diseases have been expanded worldwide [1-2]. Multiple of bacterial pathogens including P. multocida, Escherichia coli, Staphylococci, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Salmonella had become the major threats of duck health globally. Fowl cholera, occurred by P. multocida, remains one of the main problems of poultry worldwide [3]. It is a contagious disease of ducks, causing huge losses in the duck industry. The incidence of fowl cholera carriers in apparently healthy ducks could be 63%, while the mortality rate could reach 50% [4]. Moreover, Staphylococcus aureus is responsible for a broad spectrum of clinical signs in poultry including suppurative dermatitis, suppurative arthritis, and septicemic lesions [5-6]. P. aeruginosa is an opportunistic microorganism which causes several problems in ducks such as septicemia, diarrhea, respiratory manifestation, lameness, and conjunctivitis, and also, E. coli causes a wide variety of problems in ducks at different ages, but the most dangerous illness occurs at 2-6 weeks of age and mortality rates reach up to 43% [7,8]. One of the most important duck diseases is Salmonellosis. The disease is mainly showed an acute form at 3 weeks of age; the rate of chronic form in infected ducks is ranged from 0 to 66.7% in various flocks according to the age at Salmonella infection [4]. Various diseases affecting ducks may have common clinical manifestation and pathological lesions and its severity associated with the structure of duck immune system which differs from chickens and other vertebrates [8-10]. Moreover, ducks can be infected with two or more of these bacterial pathogens [9,11]. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a highly sensitive technique used to detect different specific pathogens in the clinical samples. Many PCR assays have been developed for the detection and identification of duck bacterial pathogens [12].

This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of bacterial pathogens affecting ducks as well as molecular typing of the most pathogenic strains and determination of antibiotic sensitivity of the identified strains.

Materials and Methods

Ethical approval

Handling of ducks and laboratory animals was performed according to the Animal Ethics Review Committee of Suez Canal University, Egypt.

Sampling

As illustrated in Table-1, 500 samples were randomly collected from 100 apparently healthy ducks (50 alive and 50 freshly slaughtered ducks) and 100 diseased ducks (50 alive and 50 freshly died and emergency slaughtered ducks) from commercial farms and traditional slaughterhouses at Ismailia Governorate, Egypt. Tracheal swabs and internal organs from freshly died and slaughtered ducks were collected. Samples were collected in peptone water (Oxoid, USA) under the complete aseptic conditions and rapidly transported to the lab for bacteriological examination.

Table-1.

Type and number of collected samples from examined ducks.

| Type of samples | Duck condition | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apparently healthy*(n=100) | Diseased ducks (n=100) | |||

| Live (n=50) | Freshly slaughtered (n=50) | **Live (n=50) | ***Freshly dead and emergency slaughter (n=50) | |

| Tracheal swab | 50 | - | 50 | - |

| Heart blood | - | 50 | - | 50 |

| Lung | - | 50 | - | 50 |

| Liver | - | 50 | - | 50 |

| Spleen | - | 50 | - | 50 |

| Total | 50 | 200 | 50 | 200 |

Apparently healthy birds were shown normal feed intake, smooth non-broken feathers, shiny eyes, and lack of any abnormal discharges from body orifice and no gross abnormalities.

Diseased ducks were suffered from respiratory distress and diarrhea.

Postmortem examination revealed pneumonia, airsacculitis, and liver congestion with necrotic foci

Bacteriological examination

Direct microscopical examination

Blood smears were prepared from heart blood then subjected to microscopical examination. Furthermore, the crushing of necrotic liver tissue between two slides was carried out, fixed by heating, stained by Giemsa stain, and examined microscopically for the detection of P. multocida [13].

Bacterial isolation and identification

The collected samples were inoculated in brain heart infusion broth and incubated aerobically at 37°C for 24 h. A loopful from incubated brain heart infusion broth was streaked onto nutrient agar, blood agar, mannitol salt agar, MacConkey’s agar, and eosin methylene blue agar plates then incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Separate pure colonies were picked up and inoculated on slope agar, then incubated at 37°C for 24 h, and then left for biochemical identification. Bacterial colonies were identified morphologically by using Gram’s stain as well as biochemically using methods described by Quinn et al. [13].

Serotyping of E. coli strains

The isolated E. coli strains were subjected to serological identification (slide agglutination test) according to Edwards and Ewing [14]; using E. coli polyvalent and monovalent antisera.

Serotyping of Salmonella isolates

Serodiagnosis of the isolated Salmonella strains was carried out using polyvalent (O) and monovalent antisera kit (Dade Behring Marburg GmbH–USA) D-35001, according to Grimont and Weill [15].

Pathogenicity test for P. multocida strains

The pathogenicity test was carried out according to the methods described by Levy et al. [16]. Five rabbits (4 weeks age) were involved, 0.5 ml of whole culture (P. multocida) was injected (I/P) in rabbits. Rabbits were observed for 2 days post-inoculation. P. multocida was reisolated from internal organs of the examined rabbits.

Molecular typing of Kmt1 gene of P. multocida and X region of protein-A (spA) gene of S. aureus strains

Extraction of DNA from isolates using the boiling method [17]

About 1 ml of bacterial broth culture was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min, and then the supernatant was removed. Pellets were resuspended in 1 ml distilled water, followed by centrifugation at 5000 rpm/5 min, and then resuspended in 200 µl distilled water. The suspension was boiled for 10 min, then placed in ice for 5 min, and then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant (contain the bacterial DNA) was transferred to a fresh tube. The concentration and purity of the extracted DNA were determined by estimating the optical density at wavelengths of 260 and 280 nm using the spectrophotometer. The concentration was calculated as follows: OD260 = 50 ug/ml, purity of DNA = OD260 nm/OD280 nm.

Polymerase chain reaction

Primers used in PCR (Metabion, Germany) (Table-2)

Table-2.

Oligonucleotide primers sequences used in PCR.

| Target gene | Primers sequences | Amplicon (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kmt1 | |||

| For | ATCCGCTATTTACCCAGTGG | 460 | [19] |

| Rev | GCTGTAAACGAACTCGCCAC | ||

| spA | |||

| For | TCAACAAAGAACAACAAAATGC | 226 | [20] |

| Rev | GCTTTCGGTGCTTGAGATTC |

PCR=Polymerase chain reaction, spA=X region of protein-A

DNA samples were tested in 50 μl reaction volume in a 0.2 ml PCR tube, containing PCR buffer, dNTPs(dATP, dGTP, dCTP and dTTP) 200 μM for each; two primer pairs each at 50 picomol/reaction and 1.25 unite of Taq DNA polymerase. A control negative reaction with no template DNA was also used. Thermal cycling was carried out in a programmable thermal cycler (Coy Corporation, Grass Lake, USA) [18].

PCR cycling condition

PCR protocol of Kmt1 gene was done according to the OIE 2012 [19] manual and spA gene according to Wada et al. [20]; Denaturation at 94°C for 1 min (Annealing at 55°C fo r Kmt1 gene and at 60°C for spA gene for 1 min); Extension at 72°C for 1 min run for 30 cycles with 10 min final extension at 72°C.

Screening of PCR products

About 10 µl of the amplified PCR product was analyzed by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel stained with 0.5 µg of ethidium bromide/ml. Electrophoresis was carried out in 1× TAE buffer at 80 volts for 1 h. Gels were visualized under ultraviolet transilluminator (UVP, UK) and photographed [21].

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

The susceptibility to 12 different antimicrobial agents was tested according to the instructions of NCCLS [22] manuals; using disk diffusion technique depending on the diameter of the inhibition zone [23]. The following antibiotics were tested; enrofloxacin (5 μg), norfloxacin (10 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), gentamycin (10 μg), amoxicillin (25 μg), neomycin (30 μg), erythromycin (15 μg), streptomycin (10 μg), oxytetracycline (30 μg), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (25 μg), ampicillin (10 μg), and penicillin (10 I.U); (Oxoid, USA).

Results

Postmortem examination

Postmortem examination of diseased birds revealed a picture of septicemia, blood vascular congestion, hemorrhagic enteritis, swollen, and sometimes congested liver with multiple necrotic foci on the parietal surface. Trachea and lungs were severely congested and hemorrhagic, and serofibrinous exudates were observed in the lung, liver, and heart.

Bacteriological examination

As shown in Tables-3 and 4, the bacteriological examination revealed that the most predominant strains isolated from apparently healthy and diseased ducks were P. multocida (10.4% and 25.2%), E. coli (3.6% and 22.8%), Staphylococcus epidermidis (10% and 8.8%), P. aeruginosa (2% and 10%), and Proteus vulgaris (0.8% and 10%), respectively. In addition, S. aureus and Salmonella spp. were isolated only from the diseased ducks with prevalence (12.2%) and (2.8%), respectively.

Table-3.

Prevalence of the isolated bacterial strains from apparently healthy ducks in relation to the total number of samples.

| Bacterial species | Total number of ducks | Tracheal swabs (n=50) | Total number of slaughter ducks (n=50) | Total number of isolates/total number of samples (n=250) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart (50) | Lung (50) | Liver (50) | Spleen (50) | ||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| P. multocida | 15 | 10 (20) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 3 (6) | 3 (6) | 26 (10.4) |

| E. coli | 3 | 0 (0) | 3 (6) | 3 (6) | 3 (6) | 0 (0) | 9 (3.6) |

| S. epidermidis | 10 | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 25 (10) |

| P. aeruginosa | 2 | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 5 (2) |

| P. vulgaris | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.8) |

| Total | 32 | 16 (32) | 14 (28) | 14 (28) | 14 (28) | 9 (18) | 67 (26.8) |

P. multocida=Pasteurella multocida, E. coli=Escherichia coli, S. epidermidis=Staphylococcus epidermidis, P. aeruginosa=Pseudomonas aeruginosa, P. vulgaris=Proteus vulgaris

Table-4.

Prevalence of the isolated bacterial strains from diseased ducks in relation to total number of samples.

| Bacterial species | Total number of ducks | Tracheal swabs (n=50) | Total number of slaughter ducks (n=50) | Total number of isolates/total number of samples (n=250) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart (50) | Lung (50) | Liver (50) | Spleen (50) | ||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| P. multocida | 30 | 19 (38) | 11 (22) | 11 (22) | 11 (22) | 11 (22) | 63 (25.2) |

| E. coli | 25 | 14 (28) | 11 (22) | 11 (22) | 11 (22) | 10 (20) | 57 (22.8) |

| S. aureus | 11 | 5 (10) | 6 (12) | 6 (12) | 6 (12) | 5 (10) | 28 (12.2) |

| S. epidermidis | 10 | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 4 (8) | 3 (6) | 22 (8.8) |

| P. aeruginosa | 10 | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 25 (10) |

| S. Typhimurium | 5 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (10) | 2 (4) | 7 (2.8) |

| P. vulgaris | 9 | 2 (4) | 5 (10) | 5 (10) | 7 (14) | 6 (12) | 25 (10) |

| Total | 100 | 50 (100) | 43 (86) | 43 (86) | 49 (98) | 42 (84) | 227 (90.8) |

P. multocida=Pasteurella multocida, E. coli=Escherichia coli, S. epidermidis=Staphylococcus epidermidis, P. aeruginosa=Pseudomonas aeruginosa, P. vulgaris=Proteus vulgaris, S. aureus=Staphylococcus aureus, S. Typhimurium=Salmonella Typhimurium

Serotyping of E. coli and Salmonella strains

As shown in Table-5, serological typing of 28 E. coli strains revealed that 25 strains were belonged to five different serovars O1, O18, O111, O78, and O26; moreover, three strains were untypable (isolated from diseased ducks). In addition, Salmonella serotyping proved that all the isolated Salmonella strains from the examined ducks were Salmonella Typhimurium.

Table-5.

Serotyping of the isolated E. coli strains from apparently healthy and diseased ducks.

| Serotype of E. coli | Apparently healthy ducks freshly slaughtered (n=50) | Diseased ducks | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live (n=50) | Slaughtered (n=50) | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| O1 | 1 (2) | 3 (6) | 2 (4) | 6 (21.42) |

| O18 | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | 5 (17.85) |

| O111 | - | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | 3 (10.71) |

| O78 | - | 5 (10) | 2 (4) | 7 (25) |

| O26 | - | 1 (2) | 3 (6) | 4 (14.28) |

| Untypable | - | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 3 (10.71) |

| Total | 3 (6) | 14 (28) | 11 (22) | 28 (100) |

E. coli=Escherichia coli

The pathogenicity of P. multocida

The pathogenicity of the isolated P. multocida strains was tested experimentally in five rabbits at 4 weeks age by inoculation of 0.5ml (I/P) of P. multocida broth culture, the death of inoculated rabbits usually occurs within 18-24 h. The examined died rabbits showed septicemic carcass, congested internal organs, and hemorrhage from the nose.

Molecular typing of P. multocida and S. aureus

In the present study, PCR protocol was used for amplification and detection of Kmt1gene in the isolated P. multocida strains. As shown in Figure-1, four examined isolated strains were positive for Kmt1 gene with specific amplicon size 460 bp, while three other isolated strains were negative. In addition, PCR protocol was used for amplification and detection of spA gene in the isolated S. aureus strains. Figure-2 illustrated the positive amplification of 226 bp fragment of spA gene from the extracted DNA of the isolated S. aureus strains, where all the tested strains were positive for spA gene.

Figure-1.

Electrophoretic pattern of Kmt1 gene polymerase chain reaction assay. Lane L: 100 bp DNA Ladder, Lane Pos: Control positive strain (reference strain kindly given by the Animal Health Research Institute, Dokki, Egypt). Lane Neg: Control negative. Lanes 1-4: Positive isolated Pasteurella multocida strains for Kmt1 gene at 460 bp. Lanes 5-7: Negative isolated P. multocida strains for Kmt1 gene.

Figure-2.

Electrophoretic pattern of protein A gene polymerase chain reaction assay. Lane L: 100 bp DNA ladder; Lane Pos: Control positive strain (reference strain kindly given by the Animal Health Research Institute, Dokki, Egypt). Lane Neg: Control negative. Lanes 1-4: Positive Staphylococcus aureus strains for X region of protein-A gene at 226 bp.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

As shown in Table-6, the antimicrobial susceptibility testing revealed that the isolated P. multocida, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa strains were found to be highly sensitive to enrofloxacin, norfloxacin, and ciprofloxacin. The isolated S. aureus strains were highly resistant to ampicillin, amoxicillin, and penicillin, while the isolated P. aeruginosa strains were highly resistant to penicillin, streptomycin, erythromycin, and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. In addition, E. coli serotypes and S. Typhimurium strains were highly sensitive to norfloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and enrofloxacin. S. Typhimurium strains were resistant to amoxicillin and erythromycin, while E. coli serotypes were resistant to penicillin, streptomycin, and ampicillin.

Table-6.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of the bacterial isolates from ducks (shown in percentage).

| Antimicrobial agent | P. multocida | S. aureus | P. aeruginosa | S. Typhimurium | E. coli serotypes | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | I | R | S | I | R | S | I | R | S | I | R | O1 | O18 | O78 | O26 | O111 | |

| Enrofloxacin | 100 | - | - | 100 | - | - | 100 | - | - | 100 | - | - | S | S | S | S | S |

| Norfloxacin | 100 | - | - | 100 | - | - | 100 | - | - | 100 | - | - | S | S | S | S | S |

| Ciprofloxacin | 100 | - | - | 100 | - | - | 100 | - | - | 100 | - | - | S | S | S | S | S |

| Erythromycin | 60 | 40 | - | - | 20 | 80 | - | 20 | 80 | - | 28.5 | 71.5 | S | S | S | I | I |

| Streptomycin | 20 | 80 | - | - | 10 | 90 | - | 10 | 90 | 28.5 | 71.5 | - | R | R | R | R | R |

| Ampicillin | 20 | 80 | - | - | - | 100 | - | 30 | 70 | - | 71.5 | 28.5 | R | R | R | R | R |

| Amoxicillin | 70 | 30 | - | - | - | 100 | 80 | 20 | - | - | 28.5 | 71.5 | I | R | R | R | R |

| Penicillin | 90 | 10 | - | - | - | 100 | - | - | 100 | 57 | 43 | - | R | R | R | R | R |

| Gentamycin | 90 | 10 | - | 60 | 20 | 20 | 60 | 20 | 20 | 86 | 14 | - | S | S | S | I | I |

| Neomycin | 40 | 60 | - | 80 | 20 | - | 80 | 20 | - | 86 | 14 | - | R | S | I | I | R |

| Oxytetracycline | 70 | 30 | - | - | 40 | 60 | - | 40 | 60 | 71.5 | 28.5 | - | S | R | R | R | R |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 70 | 30 | - | - | 20 | 80 | - | 20 | 80 | 86 | 14 | - | S | S | I | I | R |

S=Sensitive, I=Intermediate, R=Resistant, P. multocida=Pasteurella multocida, E. coli=Escherichia coli, P. aeruginosa=Pseudomonas aeruginosa, S. aureus=Staphylococcus aureus, S. Typhimurium=Salmonella Typhimurium

Discussion

Regarding the results shown in Tables-3 and 4, the bacteriological examination of 500 collected samples revealed the isolation of 67 bacterial strains (26.8%) from apparently healthy ducks as well as, 227 strains (90.80%) from the diseased ducks. These results are in agreement with those obtained by Rehab [24]. However, ducks are relatively resistant to certain diseases; there are many risk factors increase their susceptibility to infection such as bad management, poor sanitary conditions, malnutrition, overcrowding, and environmental stresses [25].

In the present study, the prevalence of P. multocida and E. coli was (10.4%) and (3.6%) in apparently healthy ducks, while in diseased ducks were (25.2%) and (22.8%), respectively.

Serological typing of the isolated E. coli strains revealed that 25 strains were belonged to five different serogroups including O1, O18, O111, O78, and O26; while three strains were serologically untypable (were isolated from diseased ducks) as shown in Table-5. These results are agreed with those obtained by Radad [26] and Abdel-Rahman et al., [27]. P. multocida mainly inhabits the upper respiratory tract as a commensal or an opportunistic microorganism, but its virulence increases due to stress conditions, so the microorganism invades the lung tissues [28,29]. E. coli commonly inhabits the intestinal tract, but it often infects the respiratory tracts of birds in combination with infection by other microorganisms. These infections mainly affect the air sacs and the infections are referred to as chronic respiratory disease [1]. P. multocida infection was almost constantly followed by E. coli infection in poultry [30]. In the present study, the prevalence of S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and Salmonella in diseased ducks was (12.2%), (10%), and (2.8%), respectively. Serotyping of Salmonella strains revealed that all the isolated strains were S. Typhimurium. These findings are agreed with those obtained by Mona et al. [25], Abdel-Rahman et al. [27], and Tawwab et al. [31]. S. aureus is mainly incriminated in the infection of the upper respiratory tract, especially when stress conditions increased [32]. Powerful toxins produced by P. aeruginosa are mainly incriminated in respiratory manifestation in poultry [33]. Salmonellosis is a common contagious disease of man and animal [34]. Mortality rates vary according to the degree of virulence and host immunity [5]. Results of the pathogenicity test in susceptible rabbits revealed that the isolated P. multocida strains were highly virulent and cause rabbit death within 24 h after I/P inoculation, which is accompanied by generalized septicemia. These results are agreed with those obtained by Fatma [35]. Pasteurellosis is a bacterial septicemic disease of rabbit, which affects different tissues and organs inducing pathological changes accompanied by septicemia [36]. In the present study, PCR protocol was used for amplification and detection of Kmt1gene in the isolated P. multocida strains. As illustrated in Figure-1, four examined strains were positive for Kmt1 gene with specific amplicon size 460 bp, while three strains were negative. These results agreed with those obtained by Deressa et al. [37]. Furthermore, PCR protocol used for amplification and detection of spA gene in the isolated S. aureus strains. Figure-2 illustrated the positive amplification of 226 bp fragment of spA gene from the extracted DNA of the isolated S. aureus strains, where all the tested strains were positive for spA gene; these results agreed with those obtained by Akineden et al. [38]. PCR used for amplifying specific target DNA sequences is an even more sensitive procedure either for confirming the diagnosis of the isolated microorganism or detection of specific genes that are responsible for the production of the virulence factors [39]. Regarding the results shown in Table-6, the antimicrobial susceptibility testing revealed that the isolated P. multocida strains were found to be highly sensitive to enrofloxacin, norfloxacin, and ciprofloxacin followed by penicillin and gentamycin. These results are agreed with those obtained by Balakrishnan and Roy [40] and disagree with those obtained by Akineden et al. [38]. S. aureus strains were found to be highly sensitive to enrofloxacin, norfloxacin, and ciprofloxacin and highly resistant to ampicillin, amoxicillin, and penicillin. Inactivation of penicillin resulted from the production of penicillinase enzyme by S. aureus, which causes the destruction of the beta-lactam ring of penicillin. The blaZ gene which is carried on S. aureus plasmid is mainly responsible for penicillin resistance[41]. In this study, P. aeruginosa strains were found to be highly sensitive to enrofloxacin, norfloxacin, and ciprofloxacin and were highly resistant to penicillin, streptomycin, erythromycin, and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. In addition, S. Typhimurium strains were found to be highly sensitive to enrofloxacin, norfloxacin, and ciprofloxacin. These results are agreed with those obtained by Mona et al. [25], Abdel-Rahman et al. [27], and Tawwab et al. [31]; in this concern, Hanafy et al. [42] found that enrofloxacin was the most effective antibiotic against all strains (100%) of P. aeruginosa. The multiresistant property of P. aeruginosa may be attributed to the physicochemical properties of the cell rather than antibiotic inhibitory enzymes [43]. As regard to antimicrobial susceptibility of E. coli serotypes as shown in Table-6, all the isolated E. coli serotypes were highly sensitive to enrofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and norfloxacin and were highly resistant to ampicillin. Fatma [35] recorded that the isolated E. coli serotypes were highly sensitive to enrofloxacin and highly resistant to ampicillin and streptomycin [41]. Enrofloxacin is frequently, used in the treatment of E. coli infection in poultry [44, 45].

Conclusion

P. multocida is the most predominant microorganism isolated from apparently healthy and diseased ducks followed by E. coli and Staphylococci. Enrofloxacin, norfloxacin, and ciprofloxacin are the most effective antibiotics against different bacterial pathogens affecting ducks. Combination of genotypic and phenotypic characterization is more valuable as an epidemiological tool for identification of bacterial pathogens affecting ducks; moreover, PCR is a rapid and reliable tool used for confirming the virulence of the isolated strains.

Authors’ Contributions

HME, AMA, FMY, WKE, SMH, and EMA involved in the conceptualization and design of the study. AMA, WKE, SMH, and EMA conducted the experiment and analyzed and interpreted the data. AMA, HME, FMY and WKE wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors did not receive any fund for this study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Veterinary World remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliation.

References

- 1.Friend M. Field Manual of Wildlife Diseases:General Field Procedures and Diseases of Birds. Biological Resources Division Information and Technology Report. 1999:207–214. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enany M.E, Algammal A.M, Shagar G.I, Hanora A.M, Elfeil W.K, Elshaffy N.M. Molecular typing and evaluation of sidr honey inhibitory effect on virulence genes of MRSA strains isolated from catfish in Egypt. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018;31(5):1865–1870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh R, Remington B, Blackall P, Turni C. Epidemiology of fowl cholera in free range broilers. Avian Dis. 2013;58(1):124–128. doi: 10.1637/10656-090313-Reg.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsai H.J, Hsiang P.H. The prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibilities of Salmonella and Campylobacter in ducks in Taiwan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2005;67(1):7–12. doi: 10.1292/jvms.67.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pattison M, McMullin P, Bradbury J.M. Poultry Diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elfeil W.M.K. Duck and Goose PRRs Clone, Analysis, Distributions, Polymorphism and Response to Special Ligands. China: College of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine, Jilin University; 2012. p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Demerdash M, Abdien H, Mansour D, Elfeil W. Protective efficacy of synbiotics in the prevention of Salmonella Typhimurium in chickens. Glob. Anim. Sci. J. 2015;2(2):78–85. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saif Y.M, Barnes H.J, Glisson J.R, Fadly A.M, McDougald L.R. Poultry Disease. Ames, USA: Iowa State University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abouelmaatti R.R, Algammal A.M, Li X, Ma J, Abdelnaby E.A, Elfeil W.M.K. Cloning and analysis of Nile tilapia toll-like receptors Type-3 mRNA. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 2013;38(3):277–282. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sedeik M.E, Awad A.M, Rashed H, Elfeil W.K. Variations in pathogenicity and molecular characterization of infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) in Egypt. Am. J. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2018;13(2):76–86. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tiong S. Mycoplasmas and Acholeplasmas isolated from ducks and their possible association with Pasteurella. Vet. Rec. 1990;127(3):64–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomis S, Babiuk L, Godson D.L, Allan B, Thrush T, Townsend H, Willson P, Waters E, Hecker R, Potter A. Protection of chickens against Escherichia coli infections by DNA containing CpG motifs. Infect. Immun. 2003;71(2):857–863. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.2.857-863.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quinn P.J, Markey B.K, Carter M.E, Donnelly W.J, Leonard F.C. Veterinary Microbiology and Microbial Diseases. Oxford: Block Well Science Ltd; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards P.R.A, Ewing W.H. Identification of Enterobacteriaceae. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Burges Publication Company; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grimont P.A.D, Weill F.X. Antigenic Formulae of the Salmonella serovars. France: WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Salmonella Institut Pasteur, Institut Pasteur; 2007. pp. 1–166. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ievy S, Khan M.F.R, Islam M.A, Rahman M.B. Isolation and identification of Pasteurella multocida from chicken for the preparation of oil-adjuvanted vaccine. Microbes Health. 2013;2(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heuvelink A, Van Den Biggelaar F, Zwartkruis-Nahuis J, Herbes R, Huyben R, Nagelkerke N, Melchers W, Monnens L, De Boer E. Occurrence of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 on Dutch dairy farms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1998;36(12):3480–3487. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.12.3480-3487.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elfeil W.M.K, Algammal A.M, Abouelmaatti R.R, Gerdouh A, Abdeldaim M. Molecular characterization and analysis of TLR-1 in rabbit tissues. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 2016;41(3):236–242. doi: 10.5114/ceji.2016.63121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.OIE. Haemorrhagic septicaemia. Geneva: OIE Terrestrial Manual. OIE; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wada M, Lkhagvadorj E, Bian L, Wang C, Chiba Y, Nagata S, Shimizu T, Yamashiro Y, Asahara T, Nomoto K. Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR assay for the rapid detection of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010;108(3):779–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eid H.I, Algammal A.M, Nasef S.A, Elfeil W.K, Mansour G.H. Genetic variation among avian pathogenic E. coli strains isolated from broiler chickens. Asian J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2016;11(6):350–356. [Google Scholar]

- 22.NCCLS. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing;Fifteenth Informational Supplement According to CLSI. Wayne: CLSI Document M100-s15. Standard, N.C.f.C.L. Clinical Laboratory Standard Institue; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papich M.G. VET01S-Ed3|Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria Isolated from Animals. 3rd ed. USA: College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rehab I.H.I. Some Studies on Bacterial Causes of Respiratory Troubles in Ducklings. Egypt: Department of Avian and Rabbit Medicine, Suez Canal University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mona A.A.F, Yousseff M, Dessouki A.A. Clinicopathological study on some bacterial agents causing respiratory diseases in ducks. Zag. Vet. J. 2012;40(4):46–57. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radad K.A.F. Studies on Pasteurella multocida and other bacterial pathogens associated with some problems in duck farms in Assiut governorate. Assiut Vet. Med. J. 2006;52(108):336–353. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdel-Rahman A.A, Majdi I.M, Mahmud A.A. Prevalence of Pasteurella multocida in waterfowl which suffering from respiratory disorder and its sensitivity to some different antibiotics. Assiut Vet. Med. J. 2009;55(120):267–284. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindsay R.W, Darrah P.A, Quinn K.M, Wille-Reece U, Mattei L.M, Iwasaki A, Kasturi S.P, Pulendran B, Gall J.G, Spies A.G, Seder R.A. CD8+T cell responses following replication-defective adenovirus serotype 5 immunization are dependent on CD11c+dendritic cells but show redundancy in their requirement of TLR and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor signaling. J. Immunol. 2010;185(3):1513–1521. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ranjan R, Panda S.K, Acharya A.B, Sing A.P, Gupta M.K. Molecular diagnosis of hemorrhagic septicemia. A review. Vet. World. 2011;4(4):189–192. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woo Y.K, Kim J.H. Fowl cholera outbreak in domestic poultry and epidemiological properties of Pasteurella multocida isolate. J. Microbiol. 2006;44(3):344–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tawwab A.A, Ammar A.M, Ali A.R, El Hofy F.I, Ahmed M.E.E. Detection of common (INV a) gene in salmonellae isolated from poultry using polymerase chain reaction technique. Benha Vet. Med. J. 2013;25(2):70–77. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merck Veterinary Manual 2011. 10th edition. online version. White House Station, NJ, USA: Merck sharp and Dohme carp; [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hebat-Allah A.M. Some studies on Pseudomonas species in chicken embryos and broilers in Assiut governorate. Assuit Univ. Bull. Environ. Res. 2004;7(1):23–31. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Selvaraj R, Das R, Ganguly S, Ganguli M, Dhanalakshmi S, Mukhopadhayay S. Characterization and antibiogram of Salmonella spp. From poultry specimens. J. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2010;2(9):123–126. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fatma M.Y. Clinicopathological Studies on Pasteurellosis in Laboratory Animals. Egypt: Pathology and Clinical Pathology Suez Canal University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fraser M, Bergeron A, Mays A, Susan A.E. The Merck Veterinary Manual. Merck and Co, Inc. New Jersey, U.S.A: Rahway; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deressa A, Asfaw Y, Lubke B, Kyule M.W, Tefera G, Zessin K.H. Molecular detection of Pasteurella multocida and Mannheimia haemolytica in sheep respiratory infections in Ethiopia. Int. J. Appl. Res. Vet. Med. 2010;8(2):101–110. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akineden O, Annemuller C, Hassan A.A, Lammler C, Wolter W, Zschock M. Toxin genes and other characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from milk of cows with mastitis. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2001;8(5):959–964. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.8.5.959-964.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Algammal A.M. Department of Bacteriology, Immunology and Mycology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine. Egypt: Suez Canal University; 2008. Characterization of Microorganisms Causing Subclinical Bovine Mastitis. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balakrishnan G, Roy P. Isolation, identification and antibiogram of Pasteurella multocida isolates of avian origin. Tamilnadu. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2012;8(4):199–202. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dyke K.A, Rowland S. The B lactamase transposon Tnss2. In: Novick R, editor. Molecular Biology of Staphylococci. New York: VCH Publisher; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hanafy M.S. Bacteriological studies on groundwater used in animal farms. Zag. Vet. J. 1996;24(4):94–98. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Radostits O.M.G, Gay C.C, Hinchcliff K.W, Constable P.D, Done S.H. Veterinary Medicine:A Text Book of the Diseases of Cattle, Horses, Sheep, Pigs and Goat. Oxford, UK: Saunders; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Youssef F.M, Mona A. A, Mansour D.H. Some studies on bacteriological aspects of air sacculitis and epidemiological in poultry. Assiut Vet. Med. J. 2008;54(118):284–300. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gross W.B. Diseases due to Escherichia coli in poultry. In: Gyles C.L, editor. Escherichia coli in Domestic Animals and Humans. United Kingdom, Wallingford: CAB International; 1994. pp. 237–259. [Google Scholar]