Key Points

Question

Is there an association between preoperative opioid and benzodiazepine use and postoperative mortality and persistent postoperative opioid consumption?

Findings

In this cohort study of 42 170 noncardiac surgical cases in 27 787 individuals in Iceland, increased short- and long-term mortality were significantly associated with prescription fills for opioids and benzodiazepines before surgery. The percentages of persistent postoperative opioid consumption were increased among patients receiving preoperative opioids, benzodiazepines, or both medications, a statistically significant finding.

Meaning

The findings appear to represent an opportunity for preoperative opioid and benzodiazepine medication optimization to improve postoperative outcomes.

This cohort study investigates the association between preoperative opioid and/or benzodiazepine use and postoperative mortality and persistent opioid consumption among patients undergoing noncardiac surgical procedures in Iceland.

Abstract

Importance

The number of patients prescribed long-term opioids and benzodiazepines and complications from their long-term use have increased. Information regarding the perioperative outcomes of patients prescribed these medications before surgery is limited.

Objective

To determine whether patients prescribed opioids and/or benzodiazepines within 6 months preoperatively would have greater short- and long-term mortality and increased opioid consumption postoperatively.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective, single-center, population-based cohort study included all patients 18 years or older, undergoing noncardiac surgical procedures at a national hospital in Iceland from December 12, 2005, to December 31, 2015, with follow-up through May 20, 2016. A propensity score–matched control cohort was generated using individuals from the group that received prescriptions for neither medication class within 6 months preoperatively. Data analysis was performed from April 10, 2018, to March 9, 2019.

Exposures

Patients who filled prescriptions for opioids only, benzodiazepines only, both opioids and benzodiazepines, or neither medication within 6 months preoperatively.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Long-term survival compared with propensity score–matched controls. Secondary outcomes were 30-day survival and persistent postoperative opioid consumption, defined as a prescription filled more than 3 months postoperatively.

Results

Among 41 170 noncardiac surgical cases in 27 787 individuals (16 004 women [57.6%]; mean [SD] age, 56.3 [18.8] years), a preoperative prescription for opioids only was filled for 7460 cases (17.7%), benzodiazepines only for 3121 (7.4%), and both for 2633 (6.2%). Patients who filled preoperative prescriptions for either medication class had a greater comorbidity burden compared with patients receiving neither medication class (Elixhauser comorbidity index >0 for 16% of patients filling prescriptions for opioids only, 22% for benzodiazepines only, and 21% for both medications compared with 14% for patients filling neither). There was no difference in 30-day (opioids only: 1.3% vs 1.0%; P = .23; benzodiazepines only: 1.9% vs 1.5%; P = .32) or long-term (opioids only: hazard ratio [HR], 1.12 [95% CI, 1.01-1.24]; P = .03; benzodiazepines only: HR, 1.11 [95% CI, 0.98-1.26]; P = .11) survival among the patients receiving opioids or benzodiazepines only compared with controls. However, patients prescribed both opioids and benzodiazepines had greater 30-day mortality (3.2% vs 1.8%; P = .004) and a greater hazard of long-term mortality (HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.22-1.64; P < .001). The rate of persistent postoperative opioid consumption was higher for patients filling prescriptions for opioids only (43%), benzodiazepines only (23%), or both (66%) compared with patients filling neither (12%) (P < .001 for all).

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings suggest that opioid and benzodiazepine prescription fills in the 6 months before surgery are associated with increased short-and long-term mortality and an increased rate of persistent postoperative opioid consumption. These patients should be considered for early referral to preoperative clinic and medication optimization to improve surgical outcomes.

Introduction

Because of the rapid increase in the prescription of opioids,1,2 the large number of people engaged in abuse or harmful use of opioids,3 and the associated surge in opioid-related deaths,4 there has been a call for action to fight the opioid crisis on an international level.5 In the United States, this has led to educational initiatives and statewide regulations attempting to change prescription patterns of clinicians.6 These strategies, in addition to increased awareness of the problem, have already resulted in reduction in the overall prescription of opioids, although opioid-related mortality still remains unchanged.7

One aspect of this initiative pertains to the perioperative period, during which there is an inherent risk of initiating persistent opioid use among opioid-naive patients undergoing surgery.8 This has empowered increased use of multimodal pain management strategies with a focus on nonopioid alternatives in addition to regional and neuraxial analgesia and nonpharmacologic therapies.9,10 However, 9% to 22% of patients are already long-term opioid users before surgery,2,11 and these patients are prone to higher risk of perioperative complications.12

Long-term benzodiazepine use is common,13 and the incidence of associated complications, such as hospitalizations and mortality due to overdose, has risen.14 Despite limits in the indications for long-term benzodiazepine use and its associated risks,15 there has been less awareness about the harm of long-term benzodiazepine use and fewer counteracting strategies.16 The increase in concurrent prescriptions for opioids and benzodiazepines has been associated with increased risk of hospital admission for opioid overdose.17 In addition, approximately 30% of opioid overdose deaths involve concurrent use of benzodiazepines,18 presumably because of the potentiation for opioid-induced respiratory depression.19

During 2005 through 2014, Iceland had the largest number of opioids and, in particular, benzodiazepines prescribed per inhabitant compared with the other Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden).20 In response, the Icelandic health care authorities launched a strategy to control the prescribing of opioids and benzodiazepines to reduce patient harm.20

Currently, limited data exist on the surgical outcomes of patients who are prescribed opioids, benzodiazepines, and both medications. Given concerns about the high use of opioids and benzodiazepines in surgical cohorts,2 we studied the association of prescriptions for opioids and/or benzodiazepines with short- and long-term mortality among patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. We hypothesized that there is an association between preoperative filling of prescriptions for opioids, benzodiazepines, or both medications and decreased short- and long-term survival in addition to an elevated risk of persistent opioid consumption.

Methods

This was a retrospective study of all patients aged 18 years or older undergoing noncardiac surgery at the Landspitali–The National University Hospital of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland, between December 12, 2005, and December 31, 2015, with follow-up through May 20, 2016. This is the general surgical hospital for approximately 75% of the population and is the tertiary referral hospital for the entire nation. Approval for the study was obtained from the National Bioethics Committee and the Data Protection Authority of Iceland in Reykjavik, Iceland. Individual consent was waived by both institutions as the data collection consisted exclusively of current available de-identified data from electronic health records.

Clinical Data

A comprehensive list of all procedures performed at the University Hospital during the study period was generated and classified using the Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee (NOMESCO) Classification of Surgical Procedures (NCSP-IS, version 1.14).21 Operations were classified based on surgical subspecialty, anatomic location, and extent of the surgical intervention (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Information about the American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification,22 type of anesthesia (general or regional and neuraxial), and whether the procedure was booked electively or emergently was also registered. Comorbidities were coded using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) (eTable 2 in the Supplement). The preoperative diagnosis was also used to calculate the van Walraven modification of the Elixhauser comorbidity index score23,24 and frailty risk score.25 The estimated glomerular filtration rate was calculated from serum creatinine values using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation and was used to stratify preoperative kidney function based on the worst chronic kidney disease category that patients maintained for at least 90 days preoperatively or the last preoperative serum creatinine value if 2 values more than 90 days apart were not available.26

Medication Data

Medication information for the time spanning from 1 year before surgery to 2 years after surgery was obtained from the National Prescription Drug Database of the Directorate of Health in Iceland. Medications were coded using the World Health Organization Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system and quantified using defined daily dose units and the number of filled prescriptions (eTable 3 in the Supplement).27 The defined daily dose is the average daily maintenance dose for a medication when it is used for its primary indication.27 For example, 1 defined daily dose is the oral intake of 100 mg of morphine, 20 mg of hydromorphone, or 75 mg of oxycodone per day. Similarly, 1 defined daily dose is the oral intake of 10 mg of diazepam or 2.5 mg of lorazepam per day. Patients were separated into 4 groups based on preoperative patterns of filled prescriptions within 6 months: (1) no prescription filled for opioids or benzodiazepines, (2) prescription filled for opioids but not benzodiazepines, (3) prescription filled for benzodiazepines but not opioids, and (4) prescriptions filled for both opioids and benzodiazepines. For the group that filled prescriptions for both opioids and benzodiazepines, concomitant use was noted if the patient filled a prescription for both medications in the same 30-day period up to 6 months preoperatively.

Outcome Data

The primary outcome was long-term mortality (censored at May 20, 2016), and secondary outcomes included 30-day mortality and persistent postoperative opioid consumption, defined as a patient filling a prescription for opioids more than 3 months postoperatively.28 In addition, hospital length of stay and ICD-10 diagnosis codes for myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, stroke, pneumonia, and sepsis associated with the index admission and readmissions within 90 days from discharge from primary surgery were examined. Postoperative acute kidney injury was identified using the serum creatinine component of the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria,29 as described previously.30

Data Management and Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed from April 10, 2018, through March 9, 2019. The data processing and merging of databases was carried out using custom-made Java scripts (version 1.8.0, Oracle) written by one of us (M.I.S.). All statistics were done in R, version 3.4.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) using RStudio, version 1.1.423 (RStudio, Inc). Comparisons between groups were performed using the Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables. A propensity score–matched control cohort was generated using individuals from the group who received prescriptions for neither medication class within 6 months preoperatively for the group prescribed opioids only, benzodiazepines only, or both medications. Details of the propensity score matching and subgroup analysis are in the eMethods in the Supplement. Long-term survival was compared between case patients and control individuals using a Cox proportional hazard test stratified for case-control pairs. The proportionality assumption of the Cox model was assessed by testing the correlation of the Schoenfeld residuals and logarithm of time using the cox.zph test in R. To account for multiple testing resulting from 31 independent comparisons, 2-tailed P = .002 was considered to be statistically significant when comparing patient and surgery characteristics and outcomes between the medication groups. Given that a total of 6 independent mortality analyses were performed using the propensity score–matched cohorts (excluding dose-response and subgroup analyses), P = .008 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Clinical Characteristics

A total of 42 170 surgical cases involving 27 787 individuals (16 004 women [57.6%]; mean [SD] age, 56.3 [18.8] years) were included. Orthopedic procedures (13 029; 30.9%) were most common, followed by abdominal (9628; 22.8%), neurosurgical (5019; 11.9%), and gynecological (5158; 12.2%) procedures (eTable 1 in the Supplement). A total of 28 956 (68.7%) surgical cases had no reported preoperative prescription for opioids or benzodiazepines, 7460 (17.7%) for opioids only, 3121 (7.4%) for benzodiazepines only, and 2633 (6.2%) for both opioids and benzodiazepines. For surgical cases with opioid prescriptions only, there were 6818 propensity score–matched controls; 2975 for benzodiazepines only; and 2320 for opioids and benzodiazepines. Patients who received preoperative prescription for either opioids, benzodiazepines, or both medications had a higher incidence of comorbidities, were more likely to have intermediate or high frailty score, had a higher American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification, and were more likely to be prescribed anticoagulants, hormones, antidepressants, and cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, or respiratory medications (Table 1). Among the group of patients prescribed both opioids and benzodiazepines in the 6 months preceding surgery, 80% of patients filled prescriptions for both categories of drugs concomitantly (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

Table 1. Patient Characteristics and Medication Use During the 6 Months Preceding Surgery.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P Valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neither Opioids nor Benzodiazepines (n = 28 956) | Opioids Only (n = 7460) | Benzodiazepines Only (n = 3121) | Both Opioids and Benzodiazepines (n = 2633) | ||

| Female sex | 16 098 (55.6) | 3935 (52.7) | 2163 (69.3) | 1810 (68.7) | <.001 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 55 (19) | 57 (17) | 63 (16) | 61 (15) | <.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Ischemic heart disease | 3171 (11.0) | 1038 (13.9) | 534 (17.1) | 506 (19.2) | <.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 895 (3.1) | 348 (4.7) | 170 (5.4) | 192 (7.3) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 2561 (8.8) | 870 (11.7) | 428 (13.7) | 428 (16.3) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 895 (3.1) | 343 (4.6) | 117 (3.7) | 137 (5.2) | <.001 |

| COPD | 622 (2.1) | 290 (3.9) | 189 (6.1) | 255 (9.7) | <.001 |

| eGFR<60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 4736 (16.4) | 1278 (17.1) | 671 (21.5) | 491 (18.6) | |

| Malignant neoplasm | 3100 (10.7) | 1001 (13.4) | 569 (18.2) | 514 (19.5) | <.001 |

| Benign neoplasm | 3571 (12.3) | 1159 (15.5) | 551 (17.7) | 593 (22.5) | <.001 |

| Organic psychiatric disorder | 508 (1.8) | 135 (1.8) | 63 (2.0) | 74 (2.8) | .002 |

| Substance abuse disorder | 831 (2.9) | 396 (5.3) | 213 (6.8) | 391 (14.8) | <.001 |

| Alcohol abuse | 614 (2.1) | 299 (4.0) | 154 (4.9) | 273 (10.4) | <.001 |

| Opioid abuse | 57 (0.2) | 56 (0.8) | 15 (0.5) | 67 (2.5) | <.001 |

| Hypnotic and sedative abuse | 117 (0.4) | 81 (1.1) | 57 (1.8) | 122 (4.6) | <.001 |

| Schizophrenia | 144 (0.5) | 26 (0.3) | 39 (1.2) | 23 (0.9) | <.001 |

| Mood disorder | 888 (3.1) | 368 (4.9) | 298 (9.5) | 393 (14.9) | <.001 |

| Anxiety disorder | 591 (2.0) | 232 (3.1) | 207 (6.6) | 279 (10.6) | <.001 |

| Personality disorder | 203 (0.7) | 84 (1.1) | 62 (2.0) | 81 (3.1) | <.001 |

| Frailty score classb | |||||

| Low | 25 753 (88.9) | 6284 (84.2) | 2565 (82.2) | 1894 (71.9) | <.001 |

| Intermediate | 2879 (9.9) | 1044 (14.0) | 498 (16.0) | 662 (25.1) | <.001 |

| High | 324 (1.1) | 132 (1.8) | 58 (1.9) | 77 (2.9) | <.001 |

| Elixhauser comorbidity index >0c | 4019 (13.9) | 1183 (15.9) | 679 (21.8) | 542 (20.6) | <.001 |

| Prescribed medications | |||||

| Anticoagulant | 3357 (11.6) | 1189 (15.9) | 570 (18.3) | 548 (20.8) | <.001 |

| Antiplatelet | 2214 (7.6) | 730 (9.8) | 399 (12.8) | 338 (12.8) | <.001 |

| Cardiovascular | 12 513 (43.2) | 4057 (54.4) | 2046 (65.6) | 1773 (67.3) | <.001 |

| Hormone | 5246 (18.1) | 2377 (31.9) | 1008 (32.3) | 1235 (46.9) | <.001 |

| Musculoskeletal | 9157 (31.6) | 4652 (62.4) | 1226 (39.3) | 1631 (61.9) | <.001 |

| Antidepressant | 4730 (16.3) | 2119 (28.4) | 1605 (51.4) | 1562 (59.3) | <.001 |

| Respiratory | 6861 (23.7) | 2514 (33.7) | 1260 (40.4) | 1331 (50.6) | <.001 |

| ASA physical status classificationd | |||||

| I | 8743 (31.4) | 1601 (22.3) | 355 (11.8) | 244 (9.6) | <.001 |

| II | 13 611 (48.9) | 3912 (54.6) | 1724 (57.4) | 1403 (55.3) | |

| III | 4725 (17.0) | 1453 (20.3) | 812 (27.0) | 773 (30.5) | |

| IV | 626 (2.3) | 185 (2.6) | 106 (3.5) | 104 (4.1) | |

| V | 108 (0.4) | 14 (.2) | 9 (0.3) | 11 (0.4) | |

| Primary mode of anesthesia | |||||

| General | 21 878 (78.7) | 5598 (78.3) | 2258 (75.6) | 1943 (76.7) | .005 |

| Other | 67 (0.2) | 18 (0.3) | 8 (0.3) | 5 (0.2) | |

| Regional and neuroaxial | 5871 (21.1) | 1532 (21.4) | 720 (24.1) | 584 (23.1) | |

Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiology; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

P values reflect the statistical comparison between all 4 groups.

The 3 frailty score categories consist of patients with a total frailty score of less than 5 (low), 5 to 15 (intermediate), and higher than 15 (high).

The Elixhauser comorbidity index is a severity index to quantify various patient comorbidities from multiple chronic diseases into a single number that can be used to assess and correct for patient comorbidity burden.

The ASA physical status classification is a classification system commonly used by anesthesiologists to assess the fitness of patients presenting for surgery. It has 5 categories ranging from healthy person (I) to a patient predicted to lose life or limb in the next 24 hours without the operation (V), and an additional category (VI) for a person presenting for organ donation.

Unadjusted Short-term Outcomes

Both 30-day (opioids and benzodiazepines [3.3%]; opioids only [1.2%]; benzodiazepines only [1.8%]; and neither medication [1.4%]) and 1-year mortality (opioids and benzodiazepines [11.1%]; opioids only [5.6%]; benzodiazepines [8.5%]; and neither medication [4.8%]) were greater in the group of patients who received preoperative prescriptions for both opioids and benzodiazepines compared with other groups (Table 2). Median (first-third quartile) length of stay was 2 (1-6) days for patients prescribed both opioids and benzodiazepines or benzodiazepines only vs 2 (1-4) days for patients prescribed opioids only or neither medication. Patients also had a higher rate of pneumonia (1.2% for patients prescribed both medications or benzodiazepines only vs 0.5% for patients prescribed opioids only and 0.7% for neither medication) (Table 2). Compared with patients prescribed neither medication, there was a higher ratio of patients with persistent postoperative opioid consumption (filling a prescription for opioids >3 months postoperatively) for patients in the group with preoperative prescription for opioids only (43% vs 12%; P < .001), benzodiazepines only (23% vs 12%; P < .001), or both (66% vs 12%; P < .001).

Table 2. Perioperative Outcomes in Patients and Medication Use.

| Outcome | No. (%) | P Valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neither Opioids nor Benzodiazepines (n = 28 956) | Opioids Only (n = 7460) | Benzodiazepines Only (n = 3121) | Both Opioids and Benzodiazepines (n = 2633) | ||

| Length of stay, median (IQR) | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-4) | 2 (1-6) | 2 (1-6) | <.001 |

| Complications during hospital stay | |||||

| Myocardial infarction | 42 (0.1) | 8 (0.1) | 4 (0.1) | 6 (0.2) | .56 |

| Stroke | 257 (0.9) | 35 (0.5) | 36 (1.2) | 13 (0.5) | <.001 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 29 (0.1) | 6 (0.1) | 10 (0.3) | 7 (0.3) | .001 |

| Pneumonia | 192 (0.7) | 41 (0.5) | 38 (1.2) | 31 (1.2) | <.001 |

| Sepsis | 64 (0.2) | 24 (0.3) | 5 (0.2) | 9 (0.3) | .22 |

| Acute kidney injury | 726 (7.4) | 189 (6.9) | 96 (7.0) | 77 (6.4) | .52 |

| Mortality | |||||

| 30 d | 409 (1.4) | 93 (1.2) | 55 (1.8) | 87 (3.3) | <.001 |

| 1 y | 1404 (4.8) | 419 (5.6) | 264 (8.5) | 292 (11.1) | <.001 |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

P values reflect the statistical comparison between all 4 groups.

Propensity Score–Matched Survival Analysis

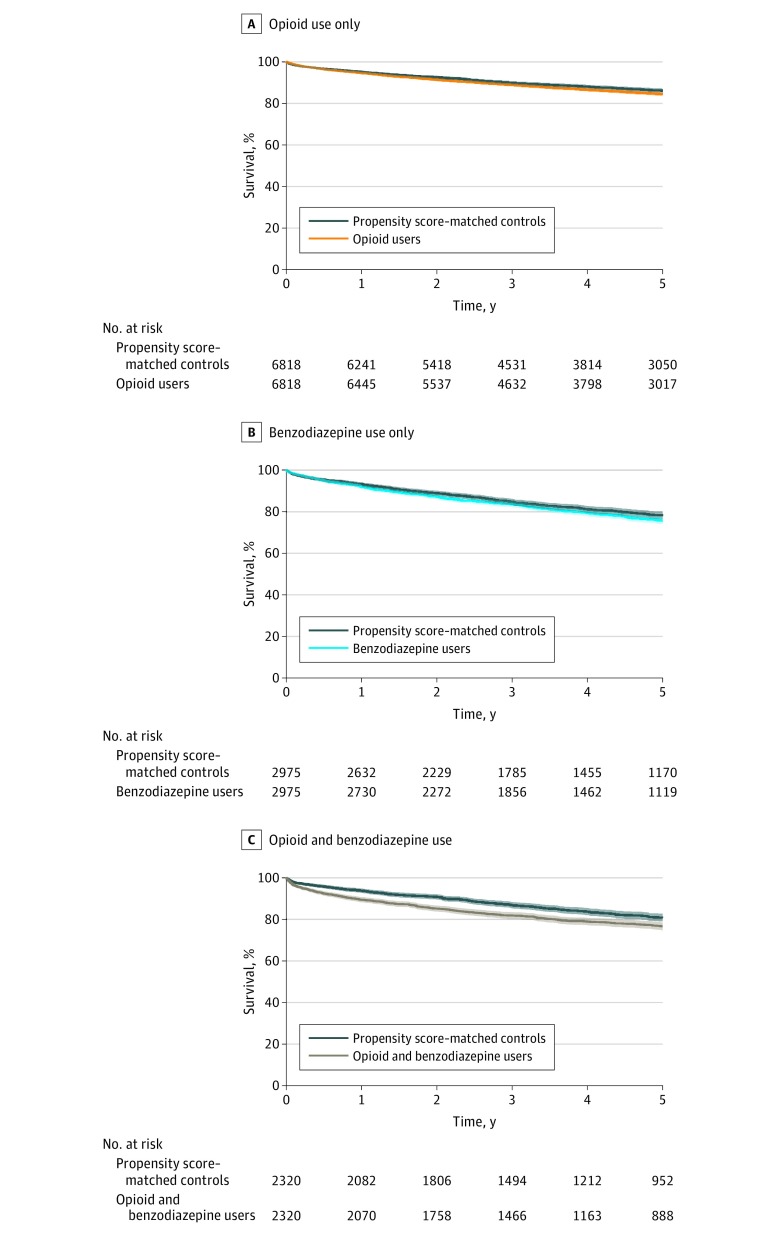

For the group receiving a preoperative prescription for opioids only, there was no difference in 30-day mortality (1.3% vs 1.0%; P = .23) or in hazard of long-term mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 1.12; 95% CI, 1.01-1.24; P = .03) (Figure 1A) compared with the control group. When patients receiving a preoperative prescription for opioids were separated into quartiles based on the cumulative amount of prescribed medication, there was no difference in 30-day mortality. There was evidence of a dose-response relationship, with reduced hazard of long-term mortality for cases in the first (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.46-0.79; P < .001) and second (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.50-0.84; P < .001) quartiles, but increased hazard for the third (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.97-1.49; P = .08) and fourth (HR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.28-1.87; P < .001) quartiles compared with controls (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Figure 1. Long-term Survival of Patients With Preoperative Prescriptions.

The shaded area represents 95% CIs.

The group that received a preoperative prescription for benzodiazepines only had no difference in 30-day mortality (1.9% vs 1.5%; P = .32) or hazard of long-term mortality (HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.98-1.26; P = .11) compared with controls (Figure 1B). In addition, there was no difference in observed 30-day or long-term mortality between case patients and controls in each quartile of amount of benzodiazepine prescribed (eFigure 3 in the Supplement).

In the group that received a preoperative prescription for both opioids and benzodiazepines, there was an increase in 30-day mortality (3.2% vs 1.8%; P = .004) and increased hazard of long-term mortality (HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.22-1.64; P < .001) compared with the control cohort (Figure 1C). After removing individuals who died within 30 days, a significantly increased hazard of long-term mortality persisted (HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.05-1.30; P = .005).

When patients who received preoperative prescriptions for both medications were separated into quartiles based on total defined daily dose of both medications, there was no difference in 30-day mortality. There was an increased hazard for long-term mortality for the third (HR, 1.67; 95% CI, 1.23-2.28; P < .001) and fourth (HR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.21-2.26; P = .001) quartiles but not the first and second quartiles (eFigure 4 in the Supplement).

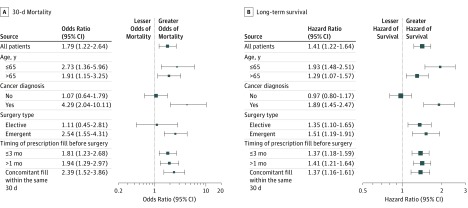

Subgroup analysis of the group of patients prescribed both opioids and benzodiazepines revealed increased odds of 30-day mortality compared with the propensity score–matched controls in all subgroups except patients without a cancer diagnosis and patients undergoing elective surgery (Figure 2A). Furthermore, there was an increased hazard of long-term mortality for patients receiving preoperative prescriptions for both opioids and benzodiazepines, compared with the propensity score–matched controls in all subgroups except patients without a cancer diagnosis (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Subgroup Analysis.

Outcomes between patients prescribed both opioids and benzodiazepines preoperatively and propensity score–matched controls. Whiskers indicate 95% CIs.

Discussion

We observed an association between the prescription patterns of opioids and benzodiazepines in the 6 months before noncardiac surgery and increased short- and long-term mortality as well as risk of persistent postoperative opioid consumption. Patients with concurrent prescriptions for opioids and benzodiazepines had greater 30-day mortality and increased hazard of long-term mortality compared with matched control patients, particularly among those prescribed the greatest quantity of medications.

Most of the existing literature12,31 regarding perioperative outcomes for patients with preoperative prescriptions for opioids and benzodiazepines involves opioids only. In the study of patients undergoing abdominal procedures by Waljee et al,12 8.8% of the cohort used opioids preoperatively; these patients had longer hospital stays, an increased discharge rate to a rehabilitation facility, and greater health care–associated costs. Similarly, Rozell et al31 reported that patients with orthopedic surgical procedures receiving preoperative opioids had higher rates of postoperative complications and greater length of stay compared with patients receiving nonopioid analgesics in the preoperative period. The incidence of preoperative opioid use in our study was 23.9% (17.7% for opioids only and 6.2% for both medications) in the 6 months preceding surgery, which is similar to what has been reported in other cohorts.2 Because many previous studies32 defined long-term preoperative use of opioids as use for more than 90 days, the present study likely included some patients receiving opioids for a shorter period. No differences in short- or long-term survival were detected in the patient cohort that received preoperative prescription for benzodiazepines only. These results reflect a recent study by Patorno et al33 that found the initiation of benzodiazepines to be associated with a small increase in mortality at 12 or 48 months.

We found that prescription for opioids, benzodiazepines, or both preoperatively was significantly associated with persistent opioid use. It has been shown that 5.9% to 6.5% of patients not receiving opioids preoperatively become persistent opioid users after major or minor surgery, defined as patients filling a prescription for opioids from 90 to 180 days postoperatively.28 We found that 43% of patients who received a preoperative prescription for opioids only and 66% of patients who received a prescription for both opioids and benzodiazepines remained persistent opioid users. However, 23% of patients prescribed benzodiazepines only became persistent opioid users compared with 12% of patients prescribed neither opioids nor benzodiazepines. This finding suggests that benzodiazepine prescription given preoperatively is a substantial risk factor for persistent postoperative opioid use. Our follow-up with respect to persistent opioid use was up to 2 years postoperatively, which is substantially longer compared with the study by Brummett et al.28

The subgroup of patients who received prescriptions for both opioids and benzodiazepines was found to have increased 30-day mortality and higher hazard of long-term mortality compared with the control group. The advanced age and increased comorbidity burden in this subgroup may be associated with more medication-related complications.34 The American Society of Geriatrics Beers criteria35 classifies benzodiazepines as potentially inappropriate medications for use in elderly patients and cautions against concurrent administration of other central nervous system–acting medications, including opioids, among patients who are receiving benzodiazepines. The potent synergistic effect of opioids and benzodiazepines that results in respiratory depression is caused by an independent pharmacologic mechanism of each drug.19 Given the limited indications for long-term use of opioids and benzodiazepines, discontinuation of these medications would particularly benefit patients with significant comorbid conditions.

With increased emphasis on the concept of the perioperative home and strategies aimed at optimizing surgical outcomes that focus on the preoperative period, our findings may be of interest and may spark initiatives to use the surgical period to reduce the potential short- and long-term harm associated with these medications. Direct educational interventions have been found to be successful in assisting patients to discontinue long-term benzodiazepine use.36 Similarly, targeted intervention to wean patients from long-term opioid use before total hip replacement has been shown to be associated with improved disease-specific and general health outcomes.37 Recently, efforts to optimize surgical outcomes by referral of high-risk patients to early (weeks to months, rather than days) preoperative assessment have been described.38 This initiative focused on timely preoperative optimization of medical comorbidities, such as diabetes, anemia, and malnutrition. Of interest, this initiative included the referral of patients receiving long-term opioids to a pain management clinic, thereby offering a strategy to reduce opioid consumption preoperatively with the hope that postoperative pain control will improve and reduce complications.38 Patients using opioids and benzodiazepines concurrently might also be a target population for preoperative clinic referral. In Iceland, a medication optimization initiative emphasizing reduction of opioid and benzodiazepine use will be added to an ongoing quality-improvement project focusing on prehabilitation and medical optimization among individuals waiting for elective orthopedic surgery.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several key strengths, including a large surgical database and complete follow-up data available for survival analysis. The centralized nationwide medication database included all medications prescribed and dispensed to every patient during the study period. This differs from previous studies that relied on a history of preoperative medication use provided by patients, often without information about medication quantity. Among notable limitations is the retrospective design, which reduced the availability and quality of other perioperative outcomes, including complications that were probably underreported and could explain the observed associations, such as respiratory depression. We did not have information about the direct cause of death for our cohort, but during the study period, only 8 to 27 individuals per year had a diagnosis associated with the use or abuse of opioids, hypnotics, or sedatives listed as the primary cause of death in Iceland.39 It is likely that harm from these medications would be considered to be a contributor to mortality given the overall comorbidity burden in the study cohort. A potential imbalance in numbers of patients with different stages of cancer might also explain the observed difference in survival. However, although a higher proportion of patients with advanced cancer might require treatment with opioids because of metastatic disease, it was not obvious that they were more likely to require both opioids and benzodiazepines. We do not know the indication for the opioid and benzodiazepine prescriptions; certain indications may have been associated with worse outcomes. This shortcoming was at least partially mitigated by propensity score matching and dose-response analysis. Our findings were hypothesis generating only, and the proper next step is testing whether an intervention to reduce opioid and benzodiazepine medication use could affect this association.

Conclusions

Patients prescribed both opioids and benzodiazepines during the 6 months preceding noncardiac surgery had greater short- and long-term mortality. The findings suggest that this group of patients should be the primary focus of further studies aimed at preoperative intervention to limit the potential harm of these medications in the perioperative setting.

eMethods

eTable 1. Classification of Surgical Procedures

eTable 2. Definition of Comorbidity and Surgical Complications by ICD-10 Codes

eTable 3. Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification Codes Used to Define Medication Groups Included in the Study

eFigure 1. Plots Illustrating Percentage of Patients Prescribed Both Opioids and Benzodiazepines in the 6 Months Preoperatively Who Filled Scripts Concomitantly (Within the Same 1-mo [30-d] Window)

eFigure 2. Dose-response Analysis of the Relationship Between Preoperative Prescription of Opioids Only and Long-term Mortality

eFigure 3. Dose-response Analysis of the Relationship Between Preoperative Prescription of Benzodiazepines Only and Long-term Mortality

eFigure 4. Dose-response Analysis of the Relationship Between Preoperative Prescription of Both Opioids and Benzodiazepines and Long-term Mortality

References

- 1.Frenk SM, Porter KS, Paulozzi LJ. Prescription opioid analgesic use among adults: United States, 1999-2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;(189):-. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jain N, Phillips FM, Weaver T, Khan SN. Preoperative chronic opioid therapy: a risk factor for complications, readmission, continued opioid use and increased costs after one- and two-level posterior lumbar fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2018;43(19):1331-1338. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dufour R, Joshi AV, Pasquale MK, et al. The prevalence of diagnosed opioid abuse in commercial and Medicare managed care populations. Pain Pract. 2014;14(3):E106-E115. doi: 10.1111/papr.12148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seth P, Scholl L, Rudd RA, Bacon S. Overdose deaths involving opioids, cocaine, and psychostimulants—United States, 2015-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(12):349-358. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6712a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murthy VH. Ending the opioid epidemic—a call to action. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(25):2413-2415. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1612578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Von Korff M, Dublin S, Walker RL, et al. The impact of opioid risk reduction initiatives on high-dose opioid prescribing for patients on chronic opioid therapy. J Pain. 2016;17(1):101-110. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Annual surveillance report of drug-related risks and outcomes—United States, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pubs/2017-cdc-drug-surveillance-report.pdf. Accessed April 26, 2018.

- 8.Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naive patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1286-1293. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131-157. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Memtsoudis SG, Poeran J, Zubizarreta N, et al. Association of multimodal pain management strategies with perioperative outcomes and resource utilization: a population-based study. Anesthesiology. 2018;128(5):891-902. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang X, Orton M, Feng R, et al. Chronic opioid usage in surgical patients in a large academic center. Ann Surg. 2017;265(4):722-727. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waljee JF, Cron DC, Steiger RM, Zhong L, Englesbe MJ, Brummett CM. Effect of preoperative opioid exposure on healthcare utilization and expenditures following elective abdominal surgery. Ann Surg. 2017;265(4):715-721. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(2):136-142. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bachhuber MA, Hennessy S, Cunningham CO, Starrels JL. Increasing benzodiazepine prescriptions and overdose mortality in the United States, 1996-2013. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):686-688. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guina J, Merrill B. Benzodiazepines I: upping the care on downers: the evidence of risks, benefits and alternatives. J Clin Med. 2018;7(2):E17. doi: 10.3390/jcm7020017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lembke A, Papac J, Humphreys K. Our other prescription drug problem. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(8):693-695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1715050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun EC, Dixit A, Humphreys K, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Association between concurrent use of prescription opioids and benzodiazepines and overdose: retrospective analysis. BMJ. 2017;356:j760. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA. 2013;309(7):657-659. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jann M, Kennedy WK, Lopez G. Benzodiazepines: a major component in unintentional prescription drug overdoses with opioid analgesics. J Pharm Pract. 2014;27(1):5-16. doi: 10.1177/0897190013515001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ministry of Health Means to reduce the abuse of medications that can cause dependence and addiction [in Icelandic]. 2018. https://www.stjornarradid.is/lisalib/getfile.aspx?itemid=3d1a8517-5f66-11e8-942c-005056bc530c. Accessed March 8, 2019.

- 21.Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee (NOMESCO) NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures (NCSP), version 1.16. 2011. http://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:968721/FULLTEXT01.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2018.

- 22.Dripps RD, Lamont A, Eckenhoff JE. The role of anesthesia in surgical mortality. JAMA. 1961;178:261-266. doi: 10.1001/jama.1961.03040420001001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Walraven C, Austin PC, Jennings A, Quan H, Forster AJ. A modification of the Elixhauser comorbidity measures into a point system for hospital death using administrative data. Med Care. 2009;47(6):626-633. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819432e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilbert T, Neuburger J, Kraindler J, et al. Development and validation of a hospital frailty risk score focusing on older people in acute care settings using electronic hospital records: an observational study. Lancet. 2018;391(10132):1775-1782. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30668-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. ; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) . A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604-612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology ATC/DDD Index 2019. Updated December 13, 2018. https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/. Accessed February 28, 2019.

- 28.Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in US adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(6):e170504. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2012;2(Suppl 1):1-138. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Long TE, Helgason D, Helgadottir S, et al. Acute kidney injury after abdominal surgery: incidence, risk factors, and outcome. Anesth Analg. 2016;122(6):1912-1920. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rozell JC, Courtney PM, Dattilo JR, Wu CH, Lee GC. Preoperative opiate use independently predicts narcotic consumption and complications after total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(9):2658-2662. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al. ; American Pain Society-American Academy of Pain Medicine Opioids Guidelines Panel . Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10(2):113-130. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patorno E, Glynn RJ, Levin R, Lee MP, Huybrechts KF. Benzodiazepines and risk of all cause mortality in adults: cohort study. BMJ. 2017;358:j2941. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watt J, Tricco AC, Talbot-Hamon C, et al. Identifying older adults at risk of harm following elective surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0986-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tannenbaum C, Martin P, Tamblyn R, Benedetti A, Ahmed S. Reduction of inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions among older adults through direct patient education: the EMPOWER cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(6):890-898. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nguyen LC, Sing DC, Bozic KJ. Preoperative reduction of opioid use before total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(9)(suppl):282-287. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.01.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aronson S, Westover J, Guinn N, et al. A perioperative medicine model for population health: an integrated approach for an evolving clinical science. Anesth Analg. 2018;126(2):682-690. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Statistics Iceland. Cause of death in Iceland 1981-2017. 2018. https://px.hagstofa.is/pxen/pxweb/en/Ibuar/Ibuar__Faeddirdanir__danir__danarmein/MAN05302.px. Accessed March 1, 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

eTable 1. Classification of Surgical Procedures

eTable 2. Definition of Comorbidity and Surgical Complications by ICD-10 Codes

eTable 3. Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification Codes Used to Define Medication Groups Included in the Study

eFigure 1. Plots Illustrating Percentage of Patients Prescribed Both Opioids and Benzodiazepines in the 6 Months Preoperatively Who Filled Scripts Concomitantly (Within the Same 1-mo [30-d] Window)

eFigure 2. Dose-response Analysis of the Relationship Between Preoperative Prescription of Opioids Only and Long-term Mortality

eFigure 3. Dose-response Analysis of the Relationship Between Preoperative Prescription of Benzodiazepines Only and Long-term Mortality

eFigure 4. Dose-response Analysis of the Relationship Between Preoperative Prescription of Both Opioids and Benzodiazepines and Long-term Mortality