Abstract

Context:

Parotid gland tumors account for 80% of all salivary gland neoplasms. Most parotid masses are operated on before obtaining the final histological diagnosis, which complicates the management of the facial nerve damage during parotid surgery.

Aims:

The aim of this study is to analyze the age- and gender-wise incidence of parotid gland tumors, the incidence of various types of tumors, to assess their clinical modes of presentation, the efficacy of treatment, and to evaluate the complications ensuing therein, because of intervention.

Settings and Design:

The present study was conducted in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, A. B. Shetty Memorial Institute of Dental Sciences and Justice K. S. Hegde Charitable Hospital, Nitte University, Mangalore.

Subjects and Methods:

A clinicopathological study of parotid gland tumors was undertaken in a tertiary care hospital. Patients with parotid swelling were clinically evaluated, followed by fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC). Surgery was planned and performed based on the tumor location and FNAC report. Patients were followed up for postoperative complications.

Results:

The study comprised 59 patients with parotid gland tumors. The age range of the patient affected was between 18 and 75 years. Benign tumors are more common than malignant tumor in the ratio of 3.5:1. Slow progressively parotid swelling was the common presenting complaint. Superficial parotidectomy was the most common surgery (69.49%) performed. The most common postoperative complication encountered was transient facial palsy (22.03%). Benign tumors were more common (77.97%). The most common benign tumor was pleomorphic adenoma, and malignant tumor was mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

Conclusions:

The incidence of parotid salivary gland tumors is increasing in recent years. Parotidectomy is safe procedure for treating parotid tumors. Transient facial palsy is the most common postoperative complication, which is reduced in superficial parotidectomy.

Keywords: Facial nerve palsy, histopathology, parotid gland tumors, parotidectomy

INTRODUCTION

Salivary gland tumors are the most complex and diverse of any organ in the body that constitutes 0.3% of all malignancies and 2%–6.5% of the head-and-neck tumor.[1] Approximately 64%–80% of all primary epithelial salivary gland tumors occur in the parotid gland and rest in other salivary glands.[2] The incidence of parotid tumor is between 1 and 3 cases/100,000/year.[3] Parotid gland tumors show a high morphological heterogeneity and presents with considerable diagnostic and management challenges. Their diagnosis and management are complicated by their relative infrequency and wide range of biologic behavior. Surgery is the main stay of treatment in parotid tumors. Fear of facial nerve injury may lead to inadequate surgery and a high recurrence rate. This prospective clinicopathological study was undertaken to analyze the age- and gender-wise incidence of parotid gland tumors, clinical modes of presentation, surgical management, histological pattern of parotid gland tumors, to assess the efficacy of treatment, and to evaluate the complications.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

A 2-year prospective clinicopathological study of parotid gland tumors was undertaken in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial surgery, A. B. Shetty Memorial Institute of Dental Sciences, and Justice K. S. Hegde Charitable Hospital, Nitte University, Mangalore, Karnataka, during the period from June 2012 to August 2014. All patients admitted for surgical treatment of parotid gland swelling were evaluated after taking an informed consent, by documenting the history, thorough local parotid examination was done regarding tumor site, location, size, deep lobe enlargement, extent, fixity to the surrounding structures, nerve involvement, and regional lymph node enlargement along with general physical examination. Routine fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC), hematological and biochemical investigations, and ultrasonography were done for all the patients before surgery. Specific radiological investigations such as X-ray of mandible and chest, computerized tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging were done in selective cases only. Surgical plan was formulated based on the clinical findings and specific investigations report. Different modalities of treatment were adopted in this study depending on the type of tumor, grade, and stage of malignant tumor. Treatment modalities included parotidectomy alone or parotidectomy with postoperative chemoradiotherapy. The resected tumor specimens were sent for histopathological confirmation and pathological staging. Following surgery, all the patients were evaluated for early and late complications. Malignant cases are referred to Oncology department, for postoperative radiotherapy/chemotherapy. All patients were asked for follow-up every month for the 1st year, every 3 months in the 2nd year to detect morbidity and recurrence. The data obtained were descriptively analyzed using SPSS software version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee.

RESULTS

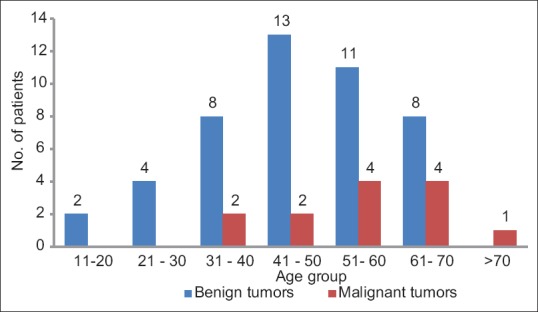

In the present study, 59 patients who presented with parotid gland neoplasms were evaluated. The age of the patient with parotid tumors in the study group ranged from 18 to 75 years, with the mean age of 48.58 years. Most patients were in the third to sixth decades of life (88.14%) [Figure 1]. Benign tumors are more common than malignant tumor in the ratio of 3.5:1. The mean age of benign tumors was 46.43 years and malignant tumors was 56.15 years. Males were more commonly affected than females in ratio of 1.4:1. The male-to-female ratio for benign tumors is 1.42:1 and the male-to-female ratio for malignant tumors is 1.16:1 [Table 1].

Figure 1.

Frequency of age distribution of benign and malignant parotid gland tumors

Table 1.

Tumor and sex distribution of parotid gland tumors

| Sex | Benign (%) | Malignant (%) | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 27 (58.70) | 7 (53.85) | 34 (57.63) |

| Female | 19 (41.30) | 6 (46.15) | 25 (42.37) |

| Total | 46 | 13 | 59 (100) |

Parotid gland tumors clinically presented with the complaints of slow progressively swelling of parotid gland (below or in front of ear lobule) [Figure 2] followed by pain (13.56%), facial palsy and trismus (1.70% each), ulceration with discharge from the swelling (3.39%), and recurrence of tumor (5.09%). The duration of swelling ranged from 1 month to 15 years. Left parotid gland (52.54%) was more commonly affected than the right parotid gland (45.76%). Bilateral parotid was affected in one case, which had Warthin's tumors. Pain in parotid swelling was encountered in 8.48% of malignant tumors and 5.09% had benign tumor. Recurrence of tumor were seen after 8–10 years of previous surgery for pleomorphic adenoma (PA), who later developed recurrent PA in one case and malignancy in two cases.

Figure 2.

A female patient with left benign parotid tumor (inset: Cut section of Pleomorphic adenoma showing tumor with glistening white mucoid areas)

Clinical examination revealed firm, hard, to rarely cystic parotid swelling. The consistency was firm to hard in most of the malignant tumor. Features of fixity, facial paralysis, and nodal involvement were considered as signs of malignancy [Figure 3]. Facial nerve palsy was seen in 1 patient, who also had associated VI, VII cranial nerve palsy. Cervical lymph node metastasis was seen in 10.17% of patients, and distant metastasis to the lung and brain was seen in one case each [Table 2]. Majority of the parotid gland tumor size encountered were between 2 and 4 cm (52.54%), followed by 4–6 cm (42.37%) and rest were >6 cm. There was no relationship between size of the parotid tumor and malignancy. A sudden increase in size of the parotid swelling was noted in one patient, which on histopathology showed malignant transformation in benign tumor. The parotid gland tumors commonly affected superficial lobe (76.27%) than deep lobe (13.56%). The ratio of superficial to deep lobe involvement is 5.6:1. Benign tumors predominantly affected superficial lobe (71.19%) and malignant tumors affected deep lobe (6.78%) and both lobes (10.17%). Clinical staging of malignant parotid tumor was done based on the history, clinical and radiological findings of the parotid tumor, lymph node involvement, and metastasis. Majority of the malignant tumors were in Stage III (30.76%) followed by Stage IVA (23.07%) and rest 15.39% each were in Stage I, II, and IVC. FNAC was done in 58 cases only. The overall diagnostic accuracy of FNAC was 93.48% of benign tumors and 91.67% for malignant tumor. Cytohistological correlation of benign and malignant tumors was 93.48% and 91.67%, respectively.

Figure 3.

A female patient with malignant right parotid tumor showing skin fixity and ulceration (inset: Cut section of malignant tumor showing irregular grey white tumor with areas of necrosis and hemorrhage)

Table 2.

Clinical signs of parotid gland tumors

| Clinical signs | Benign | Malignant | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixity to muscle/skin | 0 | 6 | 6 (10.17) |

| Deep lobe involvement | 4 | 10 | 14 (23.72) |

| Facial nerve involvement | 0 | 1 | 1 (1.70) |

| Lymph node involvement | 0 | 6 | 6 (10.17) |

| Distant metastasis | 0 | 2 | 2 (3.39) |

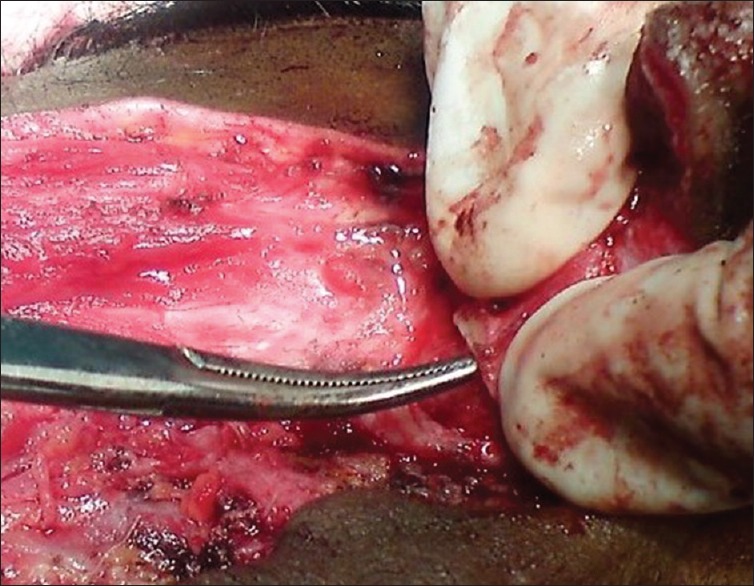

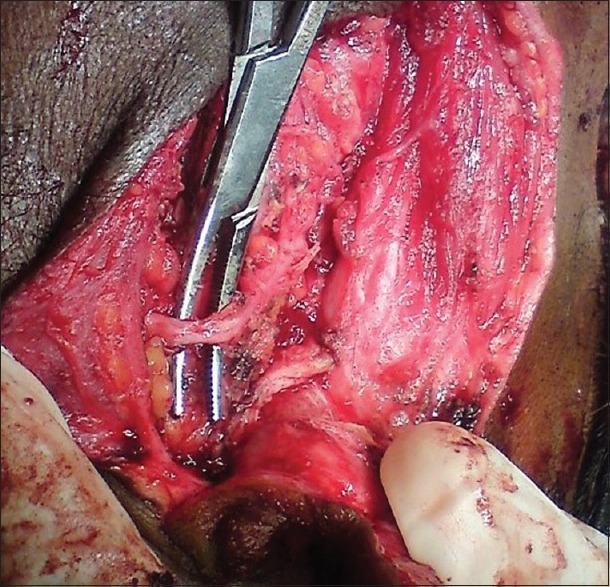

Parotidectomy is the treatment of choice for all benign and malignant parotid tumors with preservation of facial nerve [Figures 4-7]. Superficial parotidectomy was the most common surgery (69.49%) performed, followed by total conservative parotidectomy (23.73%), local excision (5.08%), and parotidectomy with modified radical neck dissection (MRND) (1.70%). Total conservative parotidectomy was done in 10 cases had malignant tumors and four cases had benign tumors, as the size of tumor was >4 cm and was involving the deep lobe of the parotid gland. Temporary facial nerve palsy was the most common postoperative complication (22.03%) encountered which later improved in for 3–6 months, followed by permanent facial palsy (6.78%) [Figure 8]. All patients who developed permanent facial palsy had malignant tumors. Other complications included wound infection and parotid fistula (3.39%) following superficial parotidectomy, which healed spontaneously within 6 weeks, Frey's syndrome and seroma (1.70% each). There was no evidence of locoregional recurrence of any of the operated cases.

Figure 4.

Modified blair incision for parotidectomy

Figure 7.

Tragal cartilage during parotidectomy

Figure 8.

Patient demonstrating postoperative complication of facial nerve palsy

Figure 5.

Upper trunk of facial nerve during parotidectomy

Figure 6.

Lower trunk of facial nerve during parotidectomy

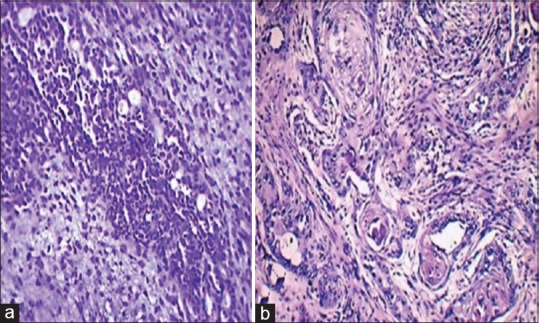

The histopathological spectrum of parotid gland tumors encountered in the study was predominantly benign tumors (77.97%) than malignant tumor (22.03%). Among benign tumors, PA was the most common tumor encountered seen in 60.87% of patients, followed by Warthin's tumor (30.44%), basal cell adenoma (6.52%), and hemangioma (2.17%) [Figure 9a]. The most common malignant tumors encountered in the study was mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC) which constituted 69.24% of cases, among which 88.9% of cases were high grade and rest were low grade. Other tumors encountered were carcinoma ex-PA, adenoid cystic carcinoma, papillary adenocarcinoma [Figure 9b], and metastatic squamous cell carcinoma (7.69% each). MEC had lymph node metastasis in six cases and distant metastasis in two cases.

Figure 9.

Microphotograph of (a) pleomorphic adenoma showing streaming’ pattern of myoepithelial cells in chondromyxoid stroma and (b) high-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma predominantly solid tumor cell clusters displaying squamoid features with keratinization and focal mucin-producing cells (H and E, ×40)

The follow-up period ranged from 3 months to 2 years. There was no evidence of locoregional recurrence in any of the operated cases, one case expired as the patient had intracranial extension and distant metastasis. To know about the late recurrence of a tumor, long-term follow-up is necessary which was not possible in this study.

DISCUSSION

Salivary gland tumors are quiet uncommon complex neoplasms accounting for 2%–6.5% of the head-and-neck tumor.[1] The incidence of the parotid tumor has increased in recent years. In the study conducted, 59 cases of parotid gland tumors were evaluated. The age range of parotid gland tumors was between 18 and 71 years, with the mean age of 48.58 years. The average age of benign parotid tumors onset showed an interesting bimodal peak of incidence as noted by Smith et al.[4] The first peak was noted between the third and fourth decades of life, which is consistent with the median age of onset for PA. The second peak, between the fifth and sixth decades, which is incongruent with the median age of onset for Warthin's tumor. Malignant parotid gland tumors are most frequently encountered between the fourth and seventh decades of life, with a mean age of 56.15 years. Most published studies show that the benign tumor occurs at younger age group than malignant tumor.[5,6,7,8,9,10] Males were commonly affected than females, with male-to-female ratio of 1.3:1 which was at par with other studies,[9,11,12] while there was female preponderance in a study by Mag et al.[13] and Takahama Junior et al.[7] Left side parotid gland (54.24%) was more commonly affected than the right parotid (44.06%). Bilateral and multicentric parotid tumor is common in the smoker, which was observed in one patient, on histopathology revealed Warthin's tumor.

The most common clinical presentation was slow progressive swelling of the parotid gland. Pain in parotid gland was the second-most common (13.56%) symptom and is more common in malignant tumors than benign tumors. Spiro found that pain is a common symptom in patients with malignant parotid gland carcinoma.[14,15] Cervical lymph node metastasis was seen in 11.86% of patients. Pain, facial palsy, lymph node involvement, fixity, and deep lobe involvement suggests malignancy. Potdar reported that the incidence of pain in malignant parotid neoplasm is 25%–33% and facial nerve paralysis is 20%–33%.[16] Facial nerve palsy is the poor prognostic sign. The clinical features are comparable to study by Lin et al.,[9] Mag et al.,[13] Takahama Junior et al.,[7] and Drivas et al.[10] [Table 2]. Recurrent parotid tumor was seen in 5.09% of cases who had previously undergone surgery 8–10 years back for PA.

Majority of the tumors are located in the superficial lobe of the parotid gland, wherein benign tumors are more common, while deep lobe can be equally affected by both benign and malignant tumors. In this study, superficial lobe was involved in 76.27% of cases, the ratio of superficial to deep lobe was 5.6:1, which is inconsistent with studies by Lin et al.[9] and Ellis et al.[17] Approximately 12%–25% of tumors are said to arise from deep lobe as per Foote et al.[18] The average size of the parotid tumor was between 2 and 4 cm (52.54%), with the median size was 4 cm. There is no relationship between tumor size and malignancy. In the study by Edward et al., 75% of patients had an average tumor size of 2–4 cm.[11] The sudden increase in the size of the parotid swelling is an indication of malignant transformation in a long-standing parotid tumor, which was noted in one case in our study. FNAC provides preoperative diagnosis, which will be helpful in planning the surgical management. Diagnostic accuracy of FNAC is 93.48% for benign tumors and 91.67% for malignant tumors, which is in comparable to studies by Ali et al.[19] and Aversa et al.[20] for benign and malignant tumors. Recent studies have confirmed a high overall accuracy rate for FNA evaluation of parotid masses, ranging from 90% to 95%.[21]

The management of the parotid gland tumors depends on the type of tumor, location, and size of the tumor. The treatment of choice for benign tumors is parotidectomy with preservation of the facial nerve. In general, the most common surgery performed is superficial partial parotidectomy with preservation of facial nerve. In this study, superficial parotidectomy was performed in 69.49% of patients, among which 39 cases were benign tumors. Total parotidectomy in benign tumors is done when the deep lobe of the parotid is involved.[22] Removal of the whole parotid lobe aims to attain adequate surgical margins and avoid rupture of the capsule, which reduces the recurrence rate.[23] The treatment of malignant parotid gland tumors depends on location, tumor-node-metastasis staging, and tumor grade. Treatment of choice for tumors in Stage I, II and low grade is partial or total parotidectomy based on the intraglandular location of tumor; the facial nerve is preserved if possible.[24,25] Radiation therapy should be used in conjunction with surgery in high-grade malignancies, tumors of the deep lobe, positive surgical margins, perineural invasion and in patients with clinically positive neck nodes, which may improve local control and increase survival rates for patients with high-grade tumors.[24,25,26] Inoperable cases were subjected to palliative chemoradiotherapy. Spiro et al. suggested that a therapeutic approach with combined surgical and radiation therapy is more appropriate than surgical treatment alone to the control of local disease.[14,15] Stage III and IV tumors are treated with total parotidectomy with or without MRND. Neck dissection is performed in the advanced stage of the tumor along with adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy. In our study, total parotidectomy was done in all malignant parotid tumors (23.73%) and along MRND in one case, as the tumor was of higher grade and stage. Ferlito et al. recently summarized the indications for neck dissection such as: in the clinically positive neck, high-grade tumors, advanced T-stage, the presence of facial nerve paralysis preoperatively, and histological demonstration of extraglandular spread or perilymphatic invasion warrant elective neck dissection.[27] Fast neutron-beam radiation therapy is superior to conventional radiation therapy using X-rays and may be curative in selected patients with recurrent disease.[28] Excision was done in 3 cases (5.08%), as the tumor was benign and superficially located all of them turned out to be Warthin's tumor on histopathology. Most of the studies avoid local excision with the fear of recurrence. However, Mag et al. performed tumor excision in 14.56% of cases.[13] Enucleation or lumpectomy must be avoided whenever possible, as it has increased risk of facial nerve lesion and recurrences. Some authors believe that the only exception to this rule could be Warthin's tumor.

Recurrences of parotid gland tumor are commonly seen in benign mixed tumor and should be minimal if the proper diagnostic approach and surgical techniques are employed. Recurrent malignant tumors have poor prognosis, regardless of tumor type or stage. Their management depends on the specific type of tumor, prior treatment, site of recurrence, and individual patient considerations. There was no evidence of locoregional recurrence in any of the operated cases in the study.

Benign tumors are more common than malignant tumors in the parotid gland. In the present study, benign tumors accounted for 77.97% and malignant tumors accounted for 22.03%, these are in comparison with studies conducted by Drivas et al.,[10] Gierek et al.,[8] Mag et al.[13] wherein benign tumors are more than malignant tumors. The reported incidence of benign tumors in parotid gland is 80%. The average prevalence of benign tumors is 75%–85% of all parotid lesions.[17] PA was the most common benign tumor encountered in the present study, accounting for 60.9%, followed by Warthin's tumor (30.4%), Basal cell adenoma (6.5%) and hemangioma (2.2%). This is in concordance with the studies conducted by Drivas et al.,[10] Gierek et al.,[8] Mag et al.,[13] and Takahama Junior et al.[7] wherein PA was the most common benign tumor followed by Warthin's tumor and BCA. Other tumors encountered in various studies include oncocytoma, myoepithelioma, lymphoepithelial neoplasms, and benign mesenchymal tumor.[7,10] MEC was the most common (69.2%) malignant tumor encountered followed by one case each (7.7%) of carcinoma ex-PA, adenocarcinoma not otherwise specified, adenoid cystic carcinoma, and metastatic poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. These are in comparison with various studies by Gierek et al.,[8] Mag et al.,[13] Takahama Junior et al.,[7] Drivas et al.,[10] and Al-Naami et al.[29] wherein MEC was the most common malignant tumor. Studies by various authors have also encountered cases such as undifferentiated carcinoma, basal cell adenocarcinoma, salivary duct carcinoma, epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma, oncocytic carcinoma, lymphoma, and mesenchymal tumor.[7,8,10,13,29]

Facial nerve palsy is the most common postoperative complication encountered following parotid surgery. In our study, temporary facial nerve palsy was seen for 18.64% of cases, the incidence is less than that noted in various studies conducted by Takahama Junior et al.[7] and Drivas et al.[10] When the size of the tumor is larger than 4 cm or is located in the deep lobe, the possibility of transient facial palsy is high. Dulguerov et al. in their study concluded that nerve stretching was the most probable etiological factor. Stretching the nerve during operation caused impairment of microcirculation to the nerve and consequent metabolic block, resulting in transient facial palsy.[30] The permanent facial was encountered in 6.78% of cases. The reported incidence of permanent facial weakness is 0%–17%, as per western literature.[31] Drivas et al. encountered permanent facial palsy in 24.2% of cases in their study which is quite high.[10] [Table 3]. Other postoperative complications include Frey syndrome, salivary fistulas, wound infection, seroma, and recurrence of tumor. There was no locoregional recurrence of tumors in our study.

Table 3.

Comparison of frequency of postoperative complications in various studies

Follow-up should be done every 4 months once during 1st year with CT scan of the parotid and neck; in 2nd year every 6 months and chest CT should be done every year for lung metastasis. To know about late recurrence of a tumor, long-term follow-up is necessary which was not possible in this study. The outlook for low-grade malignant parotid tumors is good if they are treated early, with the 5-year survival of 70%–100%. However, high-grade malignancies continue to have a poor prognosis with a 0%–50% 5-year survival, despite an aggressive surgical approach and adjuvant radiotherapy.[13] The 15-year survival for low-, intermediate-, and high-grade tumor as reported by Spiro is 54%, 31%, and 3%, respectively.[15]

CONCLUSIONS

The incidence of parotid salivary gland tumors is increasing in recent years occurring in relatively younger age group due to changing lifestyle and dietary habits. Benign parotid tumors are largely more frequent than malignant tumors. Malignant parotid tumors occur at the relatively earlier age group onset and invariably declare at the late clinical stage. Successful management depends on accurate clinical assessment and diagnosis with appropriate use of FNAC and imaging. Parotidectomy is the main modality of treatment and is safe procedures. The type of parotidectomy is planned based on the intraglandular location of the tumour. PA is the most common benign tumor and MEC is the most common malignant parotid tumor. Benign parotid tumors are treated with superficial parotidectomy. Management of malignant parotid tumor depends on the tumor stage and histological grade; those in the advanced stage are treated with total parotidectomy with MRND along with adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Transient facial palsy is the most common postoperative complication. A comprehensive understanding of the anatomy of the facial nerve with meticulous dissection is paramount to reducing the incidence of facial nerve injury during parotidectomy. The overall prognosis is good for all type of parotid gland tumors, with early proper diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Long-term follow-up is necessary as these tumors tend to recur. Since the most malignant tumor is asymptomatic and long standing benign tumor can undergo malignant change, community awareness, and early referral are necessary, as the prognosis is good if treated early.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like acknowledge the contributions of the surgeons Prof. (Dr). Rajeshwary. A, HOD, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, and Prof. (Dr). K. R. Bhagavan, HOD Department of Surgery, K. S. Hegde Medical Academy, Nitte University for kind co-operation during the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Parkin DM, Whelan SL, Ferlay J. IARC Scientific Publication No. 143. Vol. 7. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1997. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis Gray L, Auclair Paul L, Gnepp Douglas R. 2nd ed. Vol. 25. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders; 1991. Surgical Pathology of the Salivary Glands; pp. 61–91. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Witt RL. The significance of the margin in parotid surgery for pleomorphic adenoma. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:2141–54. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200212000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith WP, Langdon JD. Disorders of the salivary glands. In: Russell RG, Williams NS, Bulstrode CJ, editors. Bailey and Love's Short Practice of Surgery. 24th ed. Ch. 51. London: Arnold; 2004. pp. 718–38. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eveson JW, Cawson RA. Salivary gland tumours. A review of 2410 cases with particular reference to histological types, site, age and sex distribution. J Pathol. 1985;146:51–8. doi: 10.1002/path.1711460106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cawson RA, Eveson JW. Tumors of the salivary gland. In: Fletcher CD, editor. Diagnostic Histopathology of Tumors. 2nd ed. Ch. 7. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. pp. 167–92. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahama Junior A, Almeida OP, Kowalski LP. Parotid neoplasms: Analysis of 600 patients attended at a single institution. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;75:497–501. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)30486-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gierek T, Majzel K, Jura-Szołtys E, Slaska-Kaspera A, Witkowska M, Klimczak-Gołab L. A 20-year retrospective histoclinical analysis of parotid gland tumors in the ENT department AM in Katowice. Otolaryngol Pol. 2007;61:399–403. doi: 10.1016/S0030-6657(07)70451-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin CC, Tsai MH, Huang CC, Hua CH, Tseng HC, Huang ST. Parotid tumors: A 10-year experience. Am J Otolaryngol Head Neck Med Surg. 2008;29:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drivas EI, Skoulakis CE, Symvoulakis EK, Bizaki AG, Lachanas VA, Bizakis JG, et al. Pattern of parotid gland tumors on Crete, Greece: A retrospective study of 131 cases. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13:CR136–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edward J. Dunn, Tyler Kent, James Hines, Isidore Cohn. Parotid Neoplasms: A Report of 250 Cases and Review of the Literature. Ann. Surg. 1976;184:500–5. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197610000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Potdar GG. Mucoepidermoid tumors of salivary glands in Western India. Arch Surg. 1968;97:657–61. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1968.01340040153032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mag A, Cotulbea S, Lupescu S, Stefanescu H, Doros C, Draganescu V, et al. Parotid gland tumors. J Exp Med Surg Res. 2010;17:259–63. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spiro R, Huvos AG, Strong EW. Cancer of the parotid. A clinical pathologic study of 283 primary cases. Am J Surg. 1975;130:452–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(75)90483-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spiro RH. Salivary neoplasms: Overview of a 35-year experience with 2,807 patients. Head Neck Surg. 1986;8:177–84. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890080309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunn EJ, Kent T, Hines J, Cohn I., Jr Parotid neoplasms: A report of 250 cases and review of the literature. Ann Surg. 1976;184:500–6. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197610000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellis GL, Auclair PL. Washington DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1996. Atlas of Tumor Pathology. Tumors of the Salivary Glands. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foote FW, Jr, Frazell EL. Tumors of the major salivary glands. Cancer. 1953;6:1065–133. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195311)6:6<1065::aid-cncr2820060602>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ali NS, Nawaz A, Rajput S, Ikram M. Parotidectomy: A review of 112 patients treated at a teaching hospital in Pakistan. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11:1111–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aversa S, Ondolo C, Bollito E, Fadda G, Conticello S. Preoperative cytology in the management of parotid neoplasms. Am J Otolaryngol. 2006;27:96–100. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alphs HH, Eisele DW, Westra WH. The role of fine needle aspiration in the evaluation of parotid masses. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;14:62–6. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000193184.38310.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guntinas-Lichius O, Kick C, Klussmann JP, Jungehuelsing M, Stennert E. Pleomorphic adenoma of the parotid gland: A 13-year experience of consequent management by lateral or total parotidectomy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;261:143–6. doi: 10.1007/s00405-003-0632-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGurk M, Thomas BL, Renehan AG. Extracapsular dissection for clinically benign parotid lumps: Reduced morbidity without oncological compromise. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1610–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harish K. Management of primary malignant epithelial parotid tumors. Surg Oncol. 2004;13:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim YC, Lee SY, Kim K, Lee JS, Koo BS, Shin HA, et al. Conservative parotidectomy for the treatment of parotid cancers. Oral Oncol. 2005;41:1021–7. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen AD, Nikoghosyan A, Windemuth-Kieselbach C, Debus J, Münter MW. Combined treatment of malignant salivary gland tumours with intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and carbon ions: COSMIC. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:546. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferlito A, Rinaldo A, Silver CE, Gourin CG, Shah JP, Clayman GL, et al. Elective and therapeutic selective neck dissection. Oral Oncol. 2006;42:14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Urquhart A, Hutchins LG, Berg RL. Preoperative computed tomography scans for parotid tumor evaluation. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1984–8. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200111000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Naami MY, Guraya SY, Arafah MM, Al-Zobydi AH, Al-Tuwaijri TA. Clinicopathological pattern of malignant parotid gland tumors in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2008;29:413–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dulguerov P, Marchal F, Lehmann W. Postparotidectomy facial nerve paralysis: Possible etiologic factors and results with routine facial nerve monitoring. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:754–62. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199905000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Owen ER, Banerjee AK, Kissin M, Kark AE. Complications of parotid surgery: The need for selectivity. Br J Surg. 1989;76:1034–5. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800761016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]