Abstract

The objective of this study was to characterize biopsychosocial characteristics in children with failure to thrive with a focus on 4 domains: medical, nutrition, feeding skills, and psychosocial characteristics. A retrospective cross-sectional chart review was conducted of children assessed at the Infant and Toddler Growth and Feeding Clinic from 2015 to 2016. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data. One hundred thirty-eight children, 53.6% male, mean age 16.9 months (SD = 10.8), were included. Approximately one quarter of the children had complex medical conditions, medical comorbidities, and developmental delays. The mean weight-for-age percentile was 15.5 (SD = 23.9), and mean weight-for-length z score was −1.51 (SD = 1.4). A total of 22.5% of children had delayed oral-motor skills and 28.3% had oral aversion symptoms. Caregiver feeding strategies included force feeding (14.5%) and the use of distractions (47.1%). The multifactorial assessment of failure to thrive according to the 4 domains allowed for a better understanding of contributing factors and could facilitate multidisciplinary collaboration.

Keywords: failure to thrive, growth and development, feeding behavior, child health, child development

Background

Failure to thrive (FTT) is a sign of inadequate nutrition for optimal growth and development. FTT has multiple definitions, which include the following: weight-for-age below the third percentile; a rate of weight gain that is disproportionate to the rate of length gain; weight-for-length less than 10th percentile (in children <24 months); and a decrease in 2 or more major growth percentile curves.1,2 FTT more commonly presents in children less than 18 months of age.2 In the United States, children with FTT account for 5% to 10% of primary care pediatric patients and 3% to 5% of pediatric hospital admissions.2

Previous studies have described patient characteristics of children with failure to thrive.3-8 These studies often made a distinction between “organic” (with an underlying medical pathology) and “nonorganic” (underlying behavioral and psychological) causes.4,8-10 However, some researchers have advocated to abandon the use of the dichotomous “organic” versus “nonorganic” description of FTT.1,11,12 The dichotomous division is thought to be too simplistic for clinical and research purposes and does not capture the complexity of patients presetting with FTT. Several researchers make the case that FTT is explained by multiple biopsychosocial factors and arises from the interaction between these factors.9,11

Feeding difficulties are common in children with FTT.13 The term “feeding difficulties” is commonly used as an umbrella term that refers to a “feeding problem of some sort.”14(p345) These problems can include picky eating,13 food refusal, and not self-feeding appropriate for age.8,14 Most children with feeding difficulties present with concurrent medical, behavioral, or developmental issues.15 Pediatric feeding disorder is defined as a “an inability or refusal to eat and drink sufficient quantities of food to maintain an adequate nutritional status . . . [that may] lead to substantial organic, nutritional, or emotional consequences.”10(p380) Huh et al16 proposed a new conceptual framework to approach pediatric feeding disorders. They describe 4 integral domains that should be assessed: (1) medical, (2) nutrition, (3) feeding skills, and (4) psychosocial. The goal of this framework is to provide consistent terminology to facilitate interdisciplinary collaboration, education, and research.

Since these 4 domains also play an important role in the evaluation of children with FTT, we hypothesized that the proposed framework for pediatric feeding disorders could also be used to describe children with FTT and would give a better insight than the previous “organic” versus “nonorganic” classification. The objective of this study was to comprehensively characterize biopsychosocial characteristics in children with FTT with a focus on 4 domains: medical, nutrition, feeding skills, and psychosocial characteristics.

Methods

Design

This project was part of the Social Pediatrics Research Summer Studentship (SPRESS) program at The Hospital for Sick Children, a summer program for pre-clerkship medical students at the University of Toronto. A retrospective cross-sectional chart review of children referred to the Infant and Toddler Growth and Feeding Clinic at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Ontario, was performed.

Setting

The Infant and Toddler Growth and Feeding Clinic is a multidisciplinary, ambulatory clinic at The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Canada. Children are referred to the clinic for growth and feeding concerns to be assessed by a nurse, pediatrician, an occupational therapist (OT), a dietitian, and a social worker, often concurrently. Children were referred to the clinic from their primary care provider (family physician or pediatrician), pediatric subspecialists, or from a recent hospital admission. Children between 2 months and 5 years with a first clinic visit from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2016, were included in the study.

Procedure and Analysis

In our clinic, children’s weight were measured with a standardized scale (Scale-Tronix Pediatric Scale 4802). In children under 2 years of age the length was taken with a length board, and for those above 2 years of age height was measured with a stadiometer. Children were assessed by a pediatrician (EC, JJ, and MH) specialized in growth and feeding. A birth history, general medical history, and developmental history was taken by the pediatrician. In addition, a standardized intake form was used for new patients; in this intake form dietary intake, feeding schedule, mealtime environment (eg, family eats together), mealtime behaviors (eg, crying, throwing of food), caregiver feeding strategies (eg, use of distractions), feeding skills (eg, being fed with a spoon), and psychosocial factors (ethnicity, parental relationship) were explored. Other psychosocial factors (not included on the intake form) included maternal depression and anxiety, child protection services involvement, and financial problems. These factors were physician observed, noted on the child’s referral, or self-reported by the child’s parents or guardians. Patient data at the time of their first clinic visit were retrospectively entered into a REDCAP database by the SPRESS student (NM). A thorough chart review, including multidisciplinary documentation from subsequent clinic visits, was conducted to ensure accuracy and completeness of data at the time of their first visit. Developmental milestones17 and the World Health Organization growth calculators were used to interpret patient data.18 SPSS software was used for descriptive statistics to analyze the data.

Ethical Approval

This project was approved by The Hospital for Sick Children’s Research Ethics Board (Reference Number: 1000056884).

Results

Population Characteristics

The study population included 138 children (53.6% male) with a mean age of 16.9 (SD 10.8) months. The majority of families (n = 75, 54.3%) were from the Greater Toronto Area; 57 (41.3%) from Central Ontario. Eighty-three (60%) of the children were born in Canada. The majority of parents were born outside of Canada. Only 18.8% of the mothers were born in Canada; 6.5% were from the Philippines, 4.3% Sri Lanka, 5.1% India, 2.9% Bangladesh, 5.8% China, and 1.4% from Pakistan. The majority of families (55.1%) spoke English as the main language at home. Ninety-nine (68.1%) of the parents were married (Table 1). Most children were referred for a combination of growth and feeding concerns (n = 92, 66.7%), 13 (9.4%) children presented with only growth concerns, and 33 (23.9%) children presented with only feeding concerns.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Medical Characteristics.

| Characteristics | N = 138 |

|---|---|

| Gender (male), n, %) | 74 (53.6) |

| Age (mean age in months, SD) | 16.9 (10.8) |

| Family home address, n (%) | |

| Greater Toronto Area | 75 (54.3) |

| Central Ontario | 57 (41.3) |

| Child’s country of birth, n (%) | |

| Canada | 83 (60.1) |

| Other | 6 (4.3) |

| Unknown | 51 (37.0) |

| Mother’s country of birth, n (%) | |

| Canada | 26 (18.8) |

| Other | 61 (44.2) |

| Unknown | 51 (37.0) |

| Languages spoken at home, n (%) | |

| English | 76 (55.1) |

| Other | 62 (44.9) |

| Family relationships, n (%) | |

| Parents married/common law | 94 (68.1) |

| Single parent | 5 (3.6) |

| Other (eg, foster parents) | 18 (13.0) |

| Unknown | 19 (13.7) |

| Birth history | |

| Term, n (%) | 100 (72.5) |

| Preterm (<37 weeks), n (%) | 26 (18.8) |

| Unknown gestational age, n (%) | 12 (8.7) |

| Birthweight (kg), mean (SD)a | 2.8 (0.74) |

| Small for gestational age, n (%) | 24 (17.4) |

| Concurrent medical conditions, n (%) | |

| Genetic diagnosis | 10 (7.2) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 57 (41.3) |

| Eczema | 19 (13.8) |

| Constipation | 18 (13.0) |

| Developmental delays, n (%) | |

| Gross motor | 28 (20.3) |

| Fine motor | 11 (8.0) |

| Speech and language | 28 (20.3) |

| Social skills | 9 (6.5) |

| No developmental concerns | 81 (58.7) |

| Unknown developmental history | 5 (3.5) |

Mean birthweight calculated for n = 120 (18 missing).

Medical Characteristics

Twenty-six (18.8%) children were born prematurely and 24 (17.4%) were small for gestational age. Fifty-seven (41.3%) children had a history of gastroesophageal reflux. Thirty-nine (28.3%) used anti-reflux medication at the time of their first clinic visit. Other medical conditions that were identified included constipation (13.0%), eczema (13.8%), cardiac anomalies (7.2%), chest infections (6.5%), allergies (5.1%), and neurological disorders (7.2%). Fifty-six (40.6%) children also visited other pediatric specialists. In 10 (7.2 %) children, a genetic diagnosis (eg, Down’s syndrome, Russel-Silver) was identified. No new diagnosis of celiac disease or cystic fibrosis was made. Concurrent developmental delays were described in the gross motor (20.3%), fine motor (8.0%), speech and language (20.3%), and social domains (6.5%). Forty-one (29.7%) of the children had seen an OT specialist, 13 (9.4%) a speech-and-language pathologist, and 12 (8.7%) a physiotherapist. Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic and medical characteristics.

Nutritional Characteristics

The mean weight-for-age percentile was 15.5 (SD 23.9) months, mean height-for age percentile was 23.4 (SD 31.1), mean weight-for-length z score (children ≤24 months) was −1.51 (SD 1.4), and mean body mass index Z score (children >24 months) was −1.3 (SD 1.3). Table 2 summarizes the nutritional characteristics of our study population.

Table 2.

Nutritional Characteristics.

| Nutritional Characteristics | Growth Parameter | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Underweight | Weight-for-age <3rd percentile | 73 (53.2) |

| Severe underweight | Weight-for-age <0.1st percentile | 31 (22.5) |

| Wasted | Weight-for-heighta <3rd percentile | 35 (31.0) |

| BMIb | 7 (28.0) | |

| Severe wasted | Weight-for-heighta <0.1st percentile | 11 (9.7) |

| BMIb | 2 (8.0) | |

| Short stature | Height-for-age <3rd percentile | 51 (37.2) |

| Severe short stature | Height-for-age <0.1st percentile | 20 (15.6) |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index; WHL, weight for length.

WHL ≤ 24 months, n = 113.

BMI > 24 months, n = 25.

Twelve children (n = 8.7%) had a feeding tube in place at their first clinic visit.

One hundred two (73.9%) children were reported to be breastfed; 8.7% for less than 3 months, 13.8% for 3 to 6 months, and 39.9% for more than 6 months. Overall, 20.3% of children had a diet inappropriate for age, including inappropriate textures, prolonged formula feeding, and a delay in introducing solid foods. Thirty-nine (28.3%) children had seen a dietitian before or during their clinic visit.

Feeding Skills Characteristics

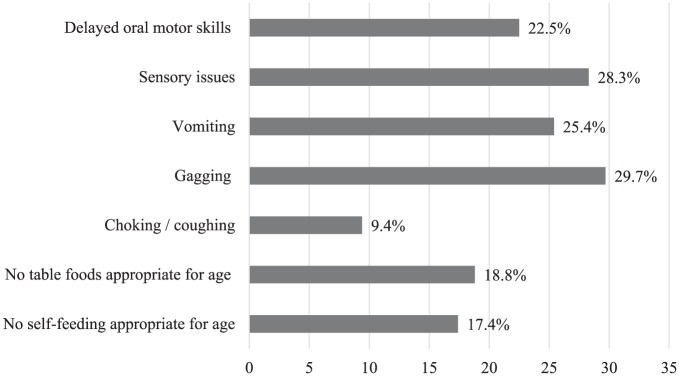

In 39 (28.3%) of the children sensory issues and oral aversion symptoms were described. Delayed oral-motor skills were identified in 31 (22.5%) children. In many children, feeding behaviors such as vomiting (25.4%), gagging (29.7%), and choking/coughing (9.4%) were reported. Feeding developmental milestones that were delayed included not-self feeding appropriate for age (17.4%). Twenty-nine (21%) new referrals to a community OT specialist were made. Figure 1 shows the percentage of feeding skills characteristics.

Figure 1.

Feeding skills characteristics.

Psychosocial Characteristics

Active or Passive Avoidance Feeding Behaviors by Child

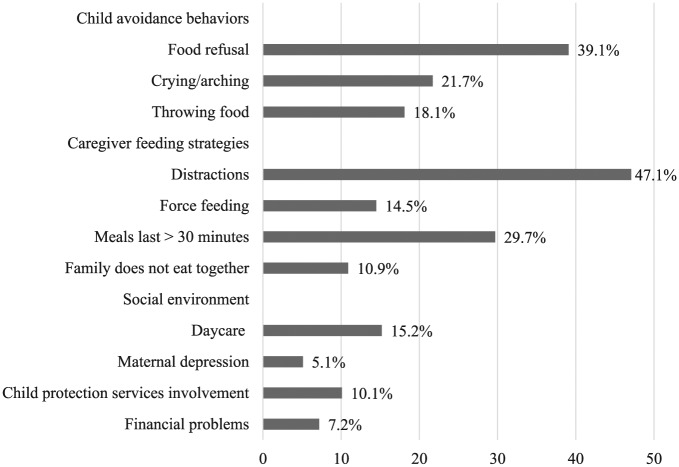

In 54 (39.1%) children, parents described active food refusal behaviors, including throwing of food (18.1%). Crying and arching were observed in 30 (21.7%) children.

Caregiver Feeding Strategies

Parents used force feeding (14.5%) and distractions (47.1%) to make their child eat. Most commonly used distractions were television (25.4%), mobile screens (15.9%), and toys (14.5%). Overall, 10.9% of the families would not eat meals together with their child. Parents reported the need to prolong mealtimes longer than 30 minutes in almost a third of the children (29.7%). Figure 2 demonstrates selected psychosocial characteristics observed in our clinic.

Figure 2.

Psychosocial characteristics.

Important factors that were identified in the child’s social environment were maternal depression (5.1%), child protection services involvement (10.1%), and financial problems (7.2%). The majority of children (63.8%) would stay at home with their caregivers (parent and/or grandparent); only 15.2% attended daycare. Maternal anxiety was reported but difficult to define.

Discussion

This study characterized biopsychosocial factors of children referred with FTT to an academic ambulatory clinic. We used a previously described model to assess medical, nutrition, feeding skills, and psychosocial factors.16 The study population consisted of a diverse patient population with the majority of parents born outside of Canada. This represents the general population in Toronto, Ontario, where nearly half of the population is foreign-born.19 Approximately one quarter of the children had complex medical conditions, medical comorbidities, and developmental delays. This is not surprising since many children with complex medical conditions have feeding and growth problems. Gastroesophageal reflux was the most common newly identified diagnosis (41.3%) in our clinic. No new diagnosis was made of cystic fibrosis or celiac disease. As previously described the yield for diagnostic testing for children with FTT is low.4

The nutritional characteristics showed that not all children met the standard anthropometric definition criteria for FTT. Only half (53.2%) of the children had a weight-for-age below the third percentile and only one third (31.0%) had a weight-for-height below the third percentile. This might reflect the main reason for referral; a minority (9.4%) of children were referred for only growth concerns and most children presented with both feeding and growth concerns (66.7%). Although some children do not meet the criteria for failure to thrive yet, their parents are often putting in tremendous efforts (eg, continuously offering food, force feeding) to maintain adequate weight gain. In our clinical experience, these children are at risk for developing a feeding aversion and further decreasing their nutritional status.

Previous studies have shown that children with FTT have a high incidence of oral-motor dysfunction,9 and poor feeding skills may also contribute to the onset and persistence of FTT. In 28.3% of the children sensory issues and oral aversion symptoms were described. Feeding behaviors such as choking/coughing may suggest oromotor dysfunction (ie, uncoordinated swallowing).14 In our population, there was a high incidence of developmental delays, which may affect age-appropriate feeding milestones. Gross motor delays affect appropriate posturing during feeds; fine motor delays interfere with the ability to self-feed; and social delays may impair the ability to participate in mealtimes with their families.20 A previous study by Black et al7 also reported that one quarter of their FTT population in a North American urban medical center to have experienced developmental risk and/or feeding problems. The high percentage of oral-motor dysfunction and poor feeding skills underscores the importance of multidisciplinary assessment. In our clinic children accessed OT therapy during the clinic meeting, but also could be referred to community OT services for support in the home environment.

The most important psychosocial factors identified in our clinic were child feeding avoidance behaviors and suboptimal caregiver feeding strategies. Parents used force feeding (14.5%) and distractions (47.1%) to make their child eat. Most commonly used distractions were television (25.4%) and mobile screens (15.9%). The percentage of force feeding is most likely underreported as many parents might not think of their feeding style as “forceful.” Mobile media devices are increasingly used to “calm” children when they are upset—parents of children with feeding challenges reported distracting their child “to get another bite in.”21 Feeding difficulties are a “relational disorder between the feeder and the child,”14 therefore feeding management strategies must be addressed in clinical assessment of children with FTT.14 In our retrospective chart review, 5.1% of the mothers self-identified as having a depressive disorder. As maternal mental health was not always discussed in clinical encounters and not part of our intake form, these results may be underrepresented. Some studies have described an association between maternal depression and poor infant growth,22,23 whereas others have shown conflicting results.24-27 Previous studies have also shown that maternal depression was significantly associated with forceful and uninvolved feeding styles.28 Maternal anxiety was often described in the clinic notes, but no care-giver self-identified with an anxiety disorder.

Although some authors still emphasize the use of the “organic” versus “nonorganic” model to describe FTT etiologies,4 others have stressed the importance to use a biopsychosocial model to describe the complex interaction between the different factors.1,9,11,12 Our study supports using the conceptual framework created by Huh et al16 to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the different contributing factors to FTT in the different domains (medical, nutritional, feeding skills, and psychosocial). This framework can also facilitate a multidisciplinary approach in children with FTT. By identifying concurrent contributing factors in children with FTT, multidisciplinary personnel and resources can be appropriately allocated and justified in institutional budgets. Last, by describing the 4 domains consistently in children with FTT the framework can facilitate education and research in FTT.

Limitations of our study include the retrospective design of our study, which may have led to selection bias. Although we used a standard clinic intake form, our questions relating to mealtime environment, mealtime behaviors, feeding skills, and psychosocial concerns were not validated and standardized and it was up to the pediatrician if all questions were asked. Our FTT population was a referred population that can make the described characteristics not generalizable to the general pediatric population with FTT. There may have been referral bias, particularly for children with child protective services involvement, as one of the clinic pediatricians also works as a child maltreatment pediatrician at the Hospital for Sick Children.

Conclusion

A more comprehensive approach to characterize children with FTT can be facilitated by assessing the medical, nutritional, feeding skills, and psychosocial domains. Children referred with FTT have dynamic biopsychosocial characteristics that extends beyond “organic” and “nonorganic” characterization. This modern characterization and multifactorial assessment allows for a better understanding of the interaction between the 4 domains and could better facilitate multidisciplinary care. Accordingly, pediatricians and primary care practitioners may like to include this comprehensive assessment of children with FTT in their practice, in order to facilitate multidisciplinary care.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Social Pediatrics Research Summer Studentship program at The Hospital for Sick Children and the University of Toronto.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: MH designed the project; all authors provided feedback on the design. NM and MH created the retrospective database and perfomred the analysis. NM collected data and wrote a first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Social Pediatrics Research Summer Studentship program at The Hospital for Sick Children and the University of Toronto and a grant from the Department of Paediatrics, Hospital of Sick Children.

ORCID iD: Nina Mazze  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0996-4992

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0996-4992

References

- 1. Perrin EC, Cole CH, Frank DA, et al. Criteria for determining disability in infants and children: failure to thrive. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 2003;(72):1-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cole SZ, Lanham JS. Failure to thrive: an update. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83:829-834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Atalay A, McCord M. Characteristics of failure to thrive in a referral population: implications for treatment. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2012;51:219-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Larson-Nath CM, Goday P. Failure to thrive: a prospective study in a pediatric gastroenterology clinic. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62:907-913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jung JS, Chang HJ, Kwon JY. Overall profile of a pediatric multidisciplinary feeding clinic. Ann Rehabil Med. 2016;40:692-701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Larson-Nath C, St Clair N, Goday P. Hospitalization for failure to thrive: a prospective descriptive report. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2018;57:212-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Black MM, Tilton N, Bento S, Cureton P, Feigelman S. Recovery in young children with weight faltering: child and household risk factors. J Pediatr. 2016;170:301-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Drewett RF, Kasese-Haraa M, Wright C. Feeding behaviour in young children who fail to thrive. Appetite. 2002;40:55-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reilly SM, Skuse DH, Stevenson J. Oral-motor dysfunction and failure to thrive. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1999;41:115-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yang HR. How to approach feeding difficulties in young children. Korean J Pediatr. 2017;60:379-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gahagan S. Failure to thrive: a consequence of undernutrition. Pediatr Rev. 2006;27:e1-e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jaffe AC. Failure to thrive: current clinical concepts. Pediatr Rev. 2011;32:100-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wright CM, Parkinson KN, Shipton D, Drewett RF. How do toddler eating problems relate to their eating behavior, food preferences, and growth? Pediatrics. 2007;120: e1069-e1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kerzner B, Milano K, MacLean WC, et al. A practical approach to classifying and managing feeding difficulties. Pediatrics. 2015;135:344-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Berlin KS, Lobato DJ, Pinkos B, Leleiko NS. Patterns of medical and developmental comorbidities among children presenting with feeding problems: a latent class analysis. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2011;32:41-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huh SY, Lukens C, Dodrill P, et al. Pediatric feeding disorder: consensus definition and conceptual framework. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2019;68:124-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dosman CF, Andrews D, Goulden KJ. Evidence-based milestone ages as a framework for developmental surveillance. Paediatr Child Health. 2012;17:561-568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. UpToDate. Pediatrics calculators. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/table-of-contents/calculators/pediatrics-calculators. Accessed June 10, 2019.

- 19. Statistics Canada. Figure 4: foreign-born as a percentage of metropolitan population, 2006. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/english/census06/analysis/immcit/charts/chart4.htm. Accessed June 10, 2019.

- 20. Bruns DA, Thompson SD. Feeding Challenges in Young Children: Strategies and Specialized Interventions for Success. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Radesky J, Peacock-Chambers E, Zuckerman B, et al. Use of mobile technology to calm upset children: associations with social-emotional development. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:397-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hassan BK, Werneck GL, Hasselmann MH. Maternal mental health and nutritional status of six-month-old infants [in Portuguese]. Rev Saude Publica. 2016;50:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Madeghe BA, Kimani VN, Vander Stoep A, Nicodimos S, Kumar M. Postpartum depression and infant feeding practices in a low income urban settlement in Nairobi-Kenya. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stewart RC. Maternal depression and infant growth—a review of recent evidence. Matern Child Nutr. 2007;3:94-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bretani A, Fink G. Maternal depression and child development: evidence from São Paulo’s Western Region Cohort Study. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2016;62:524-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. O’Brien LM, Heycock EG, Hanna M, Jones PW, Cox JL. Postnatal depression and faltering growth: a community study. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1242-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ramsay M, Gisel EG, McCusker J, Bellavance F, Platt R. Infant sucking ability, non-organic failure to thrive, maternal characteristics, and feeding practices: a prospective cohort study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2002;44:405-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hurley KM, Black MM, Papas NA, Caulfield LE. Maternal symptoms of stress, depression, and anxiety are related to nonresponsive feeding styles in a statewide sample of WIC participants. J Nutr. 2008;138:799-805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]