Abstract

Background

Timely revascularization with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) reduces death following myocardial infarction. We evaluated if a sex gap in symptom‐to‐door (STD), door‐to‐balloon (DTB), and door‐to‐PCI time persists in contemporary patients, and its impact on mortality.

Methods and Results

From 2013 to 2016 the Victorian Cardiac Outcomes Registry prospectively recruited 13 451 patients (22.5% female) from 30 centers with ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI, 47.8%) or non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) (52.2%) who underwent PCI. Adjusted log‐transformed STD and DTB time in the STEMI cohort and STD and door‐to‐PCI time in the NSTEMI cohort were analyzed using linear regression. Logistic regression was used to determine independent predictors of 30‐day mortality. In STEMI patients, women had longer log‐STD time (adjusted geometric mean ratio 1.20, 95% CI 1.12‐1.28, P<0.001), log‐DTB time (adjusted geometric mean ratio 1.12, 95% CI 1.05‐1.20, P=0.001), and 30‐day mortality (9.3% versus 6.5%, P=0.005) than men. Womens’ adjusted geometric mean STD and DTB times were 28.8 and 7.7 minutes longer, respectively, than were mens’ times. Women with NSTEMI had no difference in adjusted STD, door‐to‐PCI time, or early (<24 hours) versus late revascularization, compared with men. Female sex independently predicted a higher 30‐day mortality (odds ratio 1.67, 95% CI 1.11‐2.49, P=0.01) in STEMI but not in NSTEMI.

Conclusions

Women with STEMI have significant delays in presentation and revascularization with a higher 30‐day mortality compared with men. The delay in STD time was 4‐fold the delay in DTB time. Women with NSTEMI had no delay in presentation or revascularization, with mortality comparable to men. Public awareness campaigns are needed to address women's recognition and early action for STEMI.

Keywords: non–ST‐segment elevation acute coronary syndrome, revascularization, ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction

Subject Categories: Mortality/Survival, Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Revascularization, Women, Coronary Artery Disease

Short abstract

See Editorial Gulati

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Consistent with previous research, a significant delay in presentation and revascularization was seen in women with ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). However, no sex‐related differences were seen in non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction patients who received percutaneous intervention.

The delay in symptom‐to‐door time was 4 times the delay in door‐to‐balloon time in women with STEMI.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Ongoing public awareness campaigns are needed to address women's recognition of symptoms and early action for STEMI.

Medical professionals need to be aware of sex‐related differences in door‐to‐balloon time, and institutions should champion protocols that reduce sex discrepancies in STEMI patients.

Introduction

Worldwide, coronary artery disease is the leading cause of death for women as it is for men. Timely revascularization with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is a critical component of improving outcomes in myocardial infarction (MI). In the setting of ST‐segment–elevation MI (STEMI), emergent revascularization is key: improving door‐to‐balloon (DTB) times prevents deaths.1, 2 In non–ST‐segment–elevation MI (NSTEMI) revascularization within 24 and 72 hours for high‐ and intermediate‐risk patients, respectively, is strongly recommended.3 Markers of high‐risk NSTEMI patients include elevated cardiac biomarkers at baseline, presence of diabetes mellitus, age ≥75 years, and GRACE (Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events) score >140.4 Previous studies have identified a critical issue: that women with STEMI have delays in symptom‐to‐door (STD) and DTB times compared with their male counterparts.5, 6, 7 In addition, women around the world experience higher bleeding and heart failure following MI with increased mortality compared with men.8 There is ongoing debate as to whether this represents a true sex difference or is due to the presence of older age and comorbidities. In NSTEMI patients, sex‐related delays in STD and revascularization times have not been well described.

Over the past decade Australian public awareness campaigns targeting women have championed early recognition and treatment of MI.9 At the same time, sex discrepancies in revascularization and guideline‐based treatment have been increasingly reported in the literature. The aim of the current study was to determine if a sex gap in time to presentation and revascularization of contemporary MI patients persists. This was with the goal of identifying specific targets for future education and research. In addition, we aimed to study the impact of delays in presentation and revascularization on mortality and clinical outcomes in women versus men.

Methods

Patient Population

From 2013 to 2016, consecutive patients treated with PCI for MI (STEMI and NSTEMI) were prospectively entered into VCOR (the Victorian Cardiac Outcomes Registry). VCOR is an Australian, state‐based clinical quality registry designed to monitor the performance and outcome of PCI in Victoria. VCOR was established in 2012 and is engaged at all hospitals in Victoria (13 public and 17 private) with all patients undergoing PCI or attempted PCI entered into the registry.10 VCOR collects baseline demographic and procedural characteristics as well as in‐hospital and 30‐day outcome data on all patients who undergo PCI at a given facility through a secure web‐based data collection system. All data entry personnel are registered with VCOR, and data are entered in real time as the patient progresses through the hospital admission.11 Data integrity is ensured with regular audit activities conducted by the central registry. VCOR is funded by the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services. The study was approved by the Institutional Human Research Ethics Committee with an opt‐out consent. The deidentified data analyzed for the purpose of this study are available on request to the VCOR Data Access, Research and Publications Committee by emailing vcor@monash.edu.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Consecutive patients who received successful or attempted PCI for an MI (STEMI or NSTEMI) were included. STEMI was defined as elevated biomarkers and new or presumed new ST‐segment elevation in 2 or more contiguous leads. Patients were excluded if they experienced an MI while already an inpatient (ie, did not present to hospital with an MI) due to absence of STD time in these patients. NSTEMI was defined as the presence of elevated biomarkers and at least 1 of either ECG changes (ST‐segment depression or T‐wave abnormalities), or ischemic symptoms. Patients with an NSTEMI were additionally classified into higher‐risk subgroups due to the presence of diabetes mellitus, age ≥75 years, cardiogenic shock, or cardiac arrest on the basis of previously identified risk markers showing a benefit of an early invasive strategy in these patients.4 Preprocedural creatinine was collected up to 60 days before the PCI, and the Cockcroft‐Gault formula was used to determine estimated glomerular filtration rate. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was collected during the index admission for STEMI patients and within 6 months before the index admission and 4 weeks postdischarge for NSTEMI patients. Normal LVEF was defined as LVEF >50%, mild dysfunction as LVEF 45% to 50%, moderate dysfunction as LVEF 35% to 44%, and severe dysfunction as LVEF <35%.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

The primary outcome was unadjusted and adjusted time to presentation (STD time) and time to revascularization (DTB and door‐to‐PCI time). The STD time was calculated in both STEMI and NSTEMI patients. The DTB time was calculated for STEMI patients, and the door‐to‐PCI time calculated for NSTEMI patients. The proportion of NSTEMI patients with door‐to‐PCI time <24 hours (“early revascularization”) was determined for the total cohort and also within higher‐risk subgroups. The relevant times were defined as follows: STD as time from MI symptom onset to arrival at a PCI‐capable center, DTB as time from arrival at a PCI‐capable hospital to time of establishing flow in the culprit vessel (independent of which device was used for revascularization), and door‐to‐PCI as time from first hospital arrival to start of PCI procedure. Only STEMI patients who presented to the hospital within 12 hours of symptom onset and without interhospital transfer had DTB time collected and were included in the DTB time analysis. Secondary end points included in‐hospital and 30‐day major adverse cardiac events, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events, and major bleeding. Major adverse cardiac events were defined as death, new or recurrent MI, stent thrombosis, and target vessel revascularization. Major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events were defined as above, inclusive of stroke. The international Bleeding Academic Research Consortium standardized bleeding definitions were used to report on major bleeding events (identified by Bleeding Academic Research Consortium categories 3 and 5), including bleeding that required blood transfusion, cardiac tamponade, intracranial hemorrhage, and/or any fatal bleeding.

Statistical Analyses

Associations in categorical variables were analyzed with chi‐squared or Fisher exact tests as appropriate and expressed as number and percentage. Continuous variables were analyzed with a t‐test and were expressed as mean and standard deviation. Univariate and multivariate associations with sex were determined by logistic regression. Because the distributions of presentation and revascularization times were highly skewed, their data were log‐transformed for analysis and back‐transformed to determine an estimated geometric mean. Along with sex, variables determined a priori to be included in the multivariate models were age, diabetes mellitus, estimated glomerular filtration rate, previous PCI and/or coronary artery bypass grafting, history of peripheral vascular disease and cerebrovascular disease (CVD), LVEF, out‐of‐hospital and in‐hospital cardiac arrest, cardiogenic shock, and occurrence time of symptom onset. A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 14 (Statacorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Baseline and Pre‐, Peri‐, and Postprocedural Data

A total of 13 451 patients underwent PCI for the treatment of NSTEMI/STEMI (47.8% STEMI) of whom 3021 (22.5%) were women. Table 1 shows the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics: female patients were significantly older, with more diabetes mellitus and cerebrovascular disease, than men. Male patients had significantly higher rates of previous PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting. Pre‐ and periprocedural characteristics including medications are presented in Table 2. Radial access was used significantly less frequently in women than men in both STEMI and NSTEMI cohorts.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics According to MI Type and Sex

| STEMI | NSTEMI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n=5114) | Female (n=1317) | P Value | Male (n=5316) | Female (n=1704) | P Value | |

| Age, y | 60.8±12.2 | 66.5±13.2 | <0.001 | 63.2±12.3 | 68.1±12.7 | <0.001 |

| BMI, m2/kg | 28.3±5.0 | 28.3±6.6 | 0.90 | 28.9±5.2 | 29.1±6.5 | 0.24 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 15.1 (770) | 18.6 (245) | 0.002 | 20.6 (1097) | 24.2 (412) | 0.002 |

| eGFR, mL/min | 98.0±37.8 | 79.3±38.8 | <0.001 | 100.1±40.5 | 82.2±41.8 | <0.001 |

| Previous CABG and/or PCI | 11.3 (577) | 7.9 (104) | <0.001 | 23.3 (1240) | 17.4 (296) | <0.001 |

| CVD | 2.5 (127) | 4.3 (57) | <0.001 | 3.3 (176) | 4.3 (73) | 0.06 |

| PVD | 2.2 (110) | 1.8 (24) | 0.45 | 3.4 (181) | 3.9 (66) | 0.36 |

| OAC therapy | 2.2 (112) | 2.3 (30) | 0.85 | 4.0 (212) | 4.3 (74) | 0.52 |

| Time of symptom onset | ||||||

| 7 am to 8 pm | 63.2 (2908) | 62.7 (731) | 0.75 | 60 (2124) | 56.8 (630) | 0.06 |

| 8 pm to 7 am | 36.8 (1694) | 37.3 (435) | 40.0 (1418) | 43.2 (479) | ||

| STD time, min | 148.5 [85.2‐360.4] | 190.1 [100.5‐421.6] | <0.001 | 478.4 [146.4‐1321.6] | 485.0 [155.1‐1312.9] | 0.67 |

| Prehospital cardiac arrest | 9.6 (491) | 5.7 (75) | <0.001 | 1.0 (54) | 0.5 (8) | 0.04 |

| Prehospital ECG notification | 48.3 (2472) | 46.5 (612) | 0.24 | ··· | ··· | ··· |

Values are mean±standard deviation or % (number) or median [IQR]. BMI indicates body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IQR, interquartile range; MI, myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction; OAC, oral anticoagulation; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; STD time, symptom‐to‐door time; STEMI, ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction.

Table 2.

Pre‐ and Periprocedural Characteristics and Medications According to MI Type and Sex

| STEMI | NSTEMI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n=5114) | Female (n=1317) | P Value | Male (n=5316) | Female (n=1704) | P Value | |

| DTB time, minutes | 68 [46‐99] | 73 [50‐110] | 0.002 | ··· | ··· | ··· |

| Symptom onset to balloon time, minute | 184 [138.0‐282.4] | 212.3 [155.5‐341.0] | <0.001 | ··· | ··· | ··· |

| Radial access | 50.2 (2566) | 41.0 (540) | <0.001 | 53.5 (2843) | 44.4 (757) | <0.001 |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor | 37.8 (1933) | 31.7 (417) | <0.001 | 9.1 (485) | 7.6 (129) | 0.05 |

| Mechanical ventricular support | 4.0 (203) | 2.4 (31) | 0.005 | 0.6 (32) | 0.8 (14) | 0.33 |

| Culprit vessel | ||||||

| RCA | 38.9 (1989) | 45.0 (592) | <0.001 | 28.6 (1523) | 30.6 (522) | |

| Left main | 1.2 (60) | 1.4 (19) | 1.1 (58) | 1.2 (21) | ||

| LAD | 42.9 (2195) | 40.0 (527) | 36.8 (1954) | 41.3 (704) | <0.001 | |

| LCx | 15.5 (792) | 12.3 (162) | 29.0 (1544) | 24.4 (416) | ||

| Graft | 0.6 (30) | 0.4 (5) | 3.0 (157) | 1.6 (27) | ||

| Drug‐eluting stent | 71.3 (3428) | 70.5 (851) | 0.57 | 81.6 (4124) | 81.2 (1316) | 0.68 |

| Procedural success | 95.6 (4889) | 94.4 (1243) | 0.06 | 96.0 (5104) | 95.7 (1630) | 0.52 |

| Discharge medication | ||||||

| Aspirin | 98.2 (4720) | 97.5 (1171) | 0.14 | 98.3 (5179) | 97.6 (1644) | 0.06 |

| Thienopyridine | 34.6 (1661) | 37.3 (448) | 0.07 | 40.1 (2111) | 43.2 (727) | 0.02 |

| Ticagrelor | 63.5 (3051) | 60.2 (722) | 0.04 | 58.9 (3105) | 54.9 (924) | 0.03 |

Values are % (number) or median [IQR]. DTB time was available in 3146 male and 752 female STEMI patients. Symptom onset–to‐balloon time (ie, ischemic time) was calculated in 3136 male and 747 female patients with both symptom‐to‐door and DTB time available. DTB indicates door‐to‐balloon time; IQR, interquartile range; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCx, circumflex artery; MI, myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction; RCA, right coronary artery; STEMI, ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction.

Symptom‐to‐Door Time

The geometric mean STD time according to sex and MI type are shown in Table 3. In patients with STEMI the adjusted geometric mean STD time was significantly longer in women than men (198.0 versus 169.2 minutes, P<0.001), representing a difference of 28.8 minutes. In patients with NSTEMI there was no significant difference in both unadjusted and adjusted geometric mean STD time.

Table 3.

Adjusted Geometric Mean STD, DTB, and Door‐to‐PCI Times According to Sex

| Number | Geometric Mean, Unadjusted | 95% CI | P Value | Geometric Mean, Adjusted | 95% CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STD time | |||||||

| STEMI, min | |||||||

| Male | 4588 | 179.4 | 174.1 to 184.9 | <0.001 | 169.2 | 160.8 to 178.2 | <0.001 |

| Female | 1161 | 217.8 | 205.2 to 230.6 | 198.0 | 184.2 to 213.0 | ||

| NSTEMI, h | |||||||

| Male | 3524 | 7.71 | 7.37 to 8.07 | 0.63 | 7.76 | 7.29 to 8.25 | 0.94 |

| Female | 1104 | 7.89 | 7.28 to 8.55 | 7.79 | 7.11 to 8.54 | ||

| DTB time, min | |||||||

| STEMI | |||||||

| Male | 3146 | 72.8 | 70.87 to 74.72 | <0.001 | 81.1 | 64.89 to 70.57 | <0.001 |

| Female | 752 | 81.2 | 76.31 to 86.39 | 88.4 | 70.54 to 80.50 | ||

| Door‐to‐PCI time, h | |||||||

| NSTEMI | |||||||

| Male | 5316 | 20.40 | 19.66 to 21.17 | 0.06 | 19.75 | 18.60 to 20.97 | 0.34 |

| Female | 1704 | 21.97 | 20.55 to 23.48 | 20.65 | 18.90 to 22.58 | ||

| Symptom to balloon time, min | |||||||

| STEMI | |||||||

| Male | 3136 | 210.3 | 205.7 to 215.0 | <0.001 | 239.7 | 230.3 to 248.2 | <0.001 |

| Female | 747 | 242.7 | 231.3 to 254.7 | 269.7 | 253.4 to 283.8 | ||

Adjusted for age, diabetes mellitus, previous coronary artery bypass grafting and/or percutaneous coronary intervention, peripheral vascular and/or cerebrovascular disease, time of symptom onset (categorized as above), cardiogenic shock on arrival and out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest. Values are exponentiated regression coefficients. Adjusted values are for population mean age (63 years). Symptom‐to‐balloon time analysis was undertaken in those patients who had both STD and DTB time available. DTB time indicates door‐to‐balloon time; NSTEMI, non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous intervention; STD time, symptom‐to‐door time; STEMI, ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction.

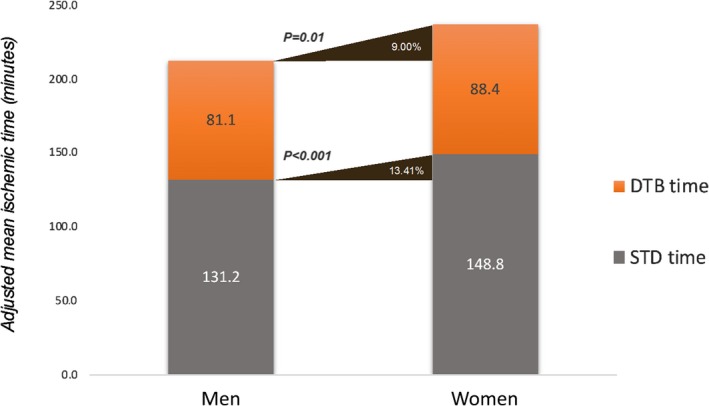

Revascularization Times

There were 753 (58%) female and 3154 (62%) male STEMI patients who presented within 12 hours of symptom onset, with no interhospital transfer. Of these, DTB time was available in 752 female and 3146 male patients, and data for both DTB and STD times were available in 747 female and 3136 male patients. The geometric mean door‐to‐PCI and DTB times according to sex and MI type are shown in Table 3. In STEMI patients the adjusted geometric mean DTB time was significantly longer in women than men (88.4 versus 81.1 minutes, P=0.01). For STEMI patients who presented within 12 hours of symptom onset, who had no interhospital transfer, and who had both STD and DTB times available, the total mean ischemic time was calculated. The time difference in mean adjusted ischemic time in STEMI patients between female and male patients was 30 minutes (P<0.0001, illustrated in Figure). A DTB time of ≤90 minutes was achieved in a significantly lower proportion of women than men (64.5% versus 69.8%, respectively, P=0.005). In NSTEMI patients there was no significant sex difference in both unadjusted and adjusted door‐to‐PCI times. Early revascularization (<24 hours) was undertaken in 43.7% and 48% (P=0.002) of women versus men with NSTEMI with no difference after adjusted logistic regression (odds ratio [OR] 1.10, 95% CI 0.95‐1.26, P=0.19). There was no significant difference in adjusted early versus late revascularization between women and men in each prespecified higher‐risk NSTEMI group: age ≥75 (OR 1.04, 95% CI 0.80‐1.35, P=0.78), diabetes mellitus (OR 1.10, 95% CI 0.87‐1.39, P=0.41), or cardiogenic shock/cardiac arrest (OR 1.07, 95% CI 0.79‐1.44, P=0.66).

Figure 1.

Adjusted mean ischemic time in female vs male STEMI patients. The total adjusted geometric mean ischemic time was calculated for STEMI patients who presented within 12 hours of symptom onset, with no interhospital transfer, and who had both symptom‐to‐door (STD) and door‐to‐balloon (DTB) time available. The adjusted mean STD and DTB times were 7.3 and 17.6 minutes longer, respectively, in women compared with men, giving a total 30‐minute delay in the geometric mean ischemic time. STEMI indicates ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction.

Clinical Outcomes

In‐hospital and 30‐day outcomes are shown in Table 4. The independent multivariate associations with 30‐day mortality according to type of MI are shown in Table 5. Female sex was an independent predictor of total mortality in the overall MI cohort (OR 1.51, CI 1.12‐2.05, P=0.007, not shown in Table 5) and in the STEMI cohort but not in NSTEMI patients. DTB and STD time were not independently associated with total mortality.

Table 4.

In‐Hospital and 30‐Day Outcomes According to MI Type and Sex

| STEMI | NSTEMI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n=5114) | Female (n=1317) | P Value | Male (n=5316) | Female (n=1704) | P Value | |

| In‐hospital outcomes | ||||||

| Total mortality | 5.7 (292) | 8.4 (110) | <0.001 | 0.7 (39) | 1.1 (18) | 0.20 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 5.5 (280) | 8.4 (110) | <0.001 | 0.6 (32) | 1.2 (21) | 0.009 |

| Stroke | 0.9 (44) | 0.6 (8) | 0.36 | 0.2 (12) | 0.2 (3) | 0.70 |

| New or recurrent MI | 1.1 (54) | 1.3 (17) | 0.47 | 0.6 (34) | 1.0 (17) | 0.13 |

| Major bleeding | 1.8 (93) | 3.4 (45) | <0.001 | 0.7 (35) | 1.3 (23) | 0.006 |

| 30‐d outcomes | ||||||

| Total mortality | 6.3 (324) | 9.3 (122) | <0.001 | 1.2 (65) | 1.5 (26) | 0.34 |

| MACE | 8.8 (452) | 11.8 (155) | 0.001 | 3.2 (170) | 3.9 (67) | 0.14 |

| MACCE | 9.5 (485) | 12.5 (164) | 0.001 | 3.4 (179) | 4.2 (71) | 0.12 |

| Major bleeding | 2.3 (117) | 4.0 (53) | <0.001 | 0.2 (12) | 0.5 (8) | 0.10 |

Values are % (number) or median [IQR]. IQR indicates interquartile range; MACCE, major cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events; MACE, major cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction; ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction.

Table 5.

Multivariate Associations With 30‐Day Mortality According to MI Type

| STEMI | NSTEMI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | OR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Age | 1.06 | 1.04 to 1.07 | <0.001 | 1.02 | 0.98 to 1.06 | 0.27 |

| Female sex | 1.67 | 1.11 to 2.49 | 0.01 | 1.37 | 0.65 to 2.52 | 0.37 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.23 | 0.80 to 1.90 | 0.35 | 1.12 | 0.59 to 2.43 | 0.76 |

| Previous CABG or PCI | 1.36 | 0.85 to 2.20 | 0.20 | 1.23 | 0.60 to 2.30 | 0.56 |

| PVD or CVD | 2.11 | 1.13 to 3.96 | 0.02 | 2.91 | 1.52 to 6.87 | 0.01 |

| Preprocedural eGFR | ··· | ··· | ··· | 0.98 | 0.97 to 0.99 | 0.04 |

| Out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest | 5.50 | 3.69 to 8.21 | <0.001 | 8.77 | 2.66 to 28.89 | <0.001 |

| Cardiogenic shock on arrival | 10.05 | 6.95 to 14.52 | <0.001 | 11.77 | 3.65 to 37.96 | <0.001 |

| Moderate LVEF impairment | 3.10 | 1.90 to 5.08 | <0.001 | 2.81 | 1.22 to 6.46 | 0.02 |

| Severe LVEF impairment | 7.56 | 4.51 to 12.69 | <0.001 | 2.29 | 0.74 to 7.04 | 0.15 |

| STD time, per h increase | 0.99 | 0.96 to 1.02 | 0.58 | 0.99 | 0.97 to 1.00 | 0.38 |

| DTB time, per min increase | 1.00 | 0.999 to 1.000 | 0.65 | ··· | ··· | ··· |

| Door‐to‐PCI time per h increase | ··· | ··· | ··· | 0.99 | 0.99 to 1.00 | 0.99 |

STEMI cohort included here was only those in whom DTB time was calculated (patients who presented within 12 hours without interhospital transfer). CABG indicates coronary artery bypass grafting; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; DTB time, door‐to‐balloon time; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction; OR, odds ratio; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; STD time, symptom‐to‐door time; STEMI, ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction.

Discussion

The current study demonstrates that contemporary female patients with STEMI treated with PCI have delayed presentation and revascularization, with higher 30‐day mortality, compared with men. After adjustment for multiple confounders women with STEMI had a 30‐minute longer ischemic time than did men. In comparison to the significant disparity in female patients with STEMI, no sex difference in adjusted time to presentation, revascularization, or mortality was seen in NSTEMI patients.

Sources of Delay

The sex‐related delay seen in STEMI patients was predominantly driven by prolonged STD time, with a delay 4 times that seen in the DTB time. Longer STD times have been linked to adverse outcomes in STEMI patients, and although DTB times have steadily decreased over the past decade, little change has been seen in the STD time.7, 12, 13, 14, 15 Campaigns around the world, including the Australian Heart Foundation's “Invisible Me,” have been conducted to increase women's awareness of the warning signs of heart attacks.9, 16, 17 Previous research has identified that women with MI experience more atypical symptoms then men, with a higher rate of associated symptoms.7, 18 However, in young patients with MI the majority of men and women experience chest pain (>85% for both).19 Yet women still take longer to seek medical contact, present less to an emergency department, and their healthcare providers are less likely to attribute their prodromal symptoms to heart disease compared with men.7, 18, 19 Our findings highlight that we must promote further public campaigns to address women's recognition and early action for STEMI symptoms.

Door‐to‐Balloon Time

The significant delay in DTB time in women presenting with STEMI seen in the current study adds to that revealed in past research.6, 20 However, this delay has previously been linked to older age and a higher burden of comorbidities in women. Our study identifies a persistent sex gap after adjustment for these known confounders. Women have been described as having higher rates of incorrect triage and delay to first ECG.20, 21 We found that the culprit lesion was more often the right coronary artery in women and the left anterior descending artery in men—perhaps resulting in more subtle ECG changes in women. However, DTB time delays in women have been previously documented even after correction for ECG characteristics.22, 23 The current study showed a similar rate of paramedic prehospital ECG notification between men and women—a process that is driven by protocol. It is therefore no surprise that implementation of a protocol focused on cardiac catheterization lab activation, a checklist‐guided early triage, guideline‐directed medical therapy, and a radial first approach in the treatment of STEMI benefited women more than men.24

In‐Hospital Complications

In line with the vast body of literature worldwide, we found that women had significantly higher in‐hospital complications, major bleeding, and total mortality following MI compared with men.25, 26 Female sex was an independent predictor of higher mortality in STEMI patients independent of age and risk factors.27 Although MI occurs 3 to 4 times more frequently in men in younger patients, women represent the majority of patients >75 years.28 With an aging population, a persistent sex gap in the STEMI cohort must be of global concern. In our study incremental increases in STD and DTB times were univariate predictors of 30‐day mortality but were not found to be independent predictors. Nevertheless, the time‐dependent ischemic cell death that occurs in STEMI, and hence the importance of early revascularization with a DTB time ≤90 minutes, has been well established.13, 29 Women with STEMI in our study had significantly lower rates of radial access, higher bleeding events, and less appropriate secondary prevention medications. The lower radial access use likely contributed to the higher bleeding events and potentially the higher observed mortality in women, and increasing radial access in women warrants further study.30, 31

NSTEMI Patients

In patients with NSTEMI an early invasive approach has been associated with a reduction in ischemia and even mortality in high‐risk subsets.4, 32 However, conflicting results in sex differences have been seen in regard to presentation delays and the benefit of timely PCI.33, 34 In the current study female sex in NSTEMI was not associated with a delay in STD or door‐to‐PCI time and led to no increased mortality after adjustment for confounders. Analysis of early (<24 hours) versus late revascularization in higher‐risk NSTEMI cohorts still demonstrated no sex difference. The current study only included patients who underwent PCI for NSTEMI. Previous studies showing a sex‐related gap in NSTEMI patients may reflect the lower rates of invasive angiography or PCI in women overall.35

Limitations

The current study is limited by its observational nature. Analysis to correct for confounders was performed, but we can only correct for known or measured confounders. Within the registry, DTB time was calculated only in STEMI patients who presented directly to a PCI‐capable hospital. Hence, we cannot comment on DTB times in patients who underwent interhospital transfer from a peripheral hospital. We can only speculate on the reasons for the longer ischemic time seen in women, as registry data did not include presenting symptoms, type of first medical contact, or transportation to the hospital. Preprocedural creatinine was not collected in ≈20% of STEMI patients, and hence, renal failure could not be factored into the multivariate analysis in this group. A high‐risk NSTEMI cohort was defined as patients with the presence of previously identified high‐risk features from meta‐analyses. A GRACE score was not able to be calculated due to the lack of all baseline data required (blood pressure, heart rate, Killip class). The registry included only patients who underwent PCI or attempted PCI for MI; hence, we cannot draw any conclusions about sex bias that results from not investigating or treating female MI patients with invasive angiography.

Conclusions

Significant sex‐related disparity persists in women with STEMI, with adjusted delays in presentation, revascularization, and a higher mortality compared with men. In comparison, no sex‐related difference was seen in NSTEMI patients treated with PCI. Continued public awareness campaigns targeting recognition of STEMI symptoms in women and ongoing studies analyzing delays at the medical profession level are urgently needed to close the gap.

Sources of Funding

No funding was received for the current study. Dr Zaman has been supported by a fellowship (101993) from the National Heart Foundation of Australia, a Monash University Early Career Practitioner Fellowship, and a Robertson Research Cardiologist Fellowship.

Disclosures

None.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e012161 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012161.)

References

- 1. Cannon CP, Gibson CM, Lambrew CT, Shoultz DA, Levy D, French WJ, Gore JM, Weaver WD, Rogers WJ, Tiefenbrunn AJ. Relationship of symptom‐onset‐to‐balloon time and door‐to‐balloon time with mortality in patients undergoing angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2000;283:2941–2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli‐Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimsky P; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation: the Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, Mueller C, Valgimigli M, Andreotti F, Bax JJ, Borger MA, Brotons C, Chew DP, Gencer B, Hasenfuss G, Kjeldsen K, Lancellotti P, Landmesser U, Mehilli J, Mukherjee D, Storey RF, Windecker S; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST‐segment elevation: Task force for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST‐segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:267–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jobs A, Mehta SR, Montalescot G, Vicaut E, Van't Hof AWJ, Badings EA, Neumann FJ, Kastrati A, Sciahbasi A, Reuter PG, Lapostolle F, Milosevic A, Stankovic G, Milasinovic D, Vonthein R, Desch S, Thiele H. Optimal timing of an invasive strategy in patients with non‐ST‐elevation acute coronary syndrome: a meta‐analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2017;390:737–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Berger JS, Elliott L, Gallup D, Roe M, Granger CB, Armstrong PW, Simes RJ, White HD, Van de Werf F, Topol EJ, Hochman JS, Newby LK, Harrington RA, Califf RM, Becker RC, Douglas PS. Sex differences in mortality following acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2009;302:874–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roswell RO, Kunkes J, Chen AY, Chiswell K, Iqbal S, Roe MT, Bangalore S. Impact of sex and contact‐to‐device time on clinical outcomes in acute ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction‐findings from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e004521 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sederholm Lawesson S, Isaksson RM, Ericsson M, Angerud K, Thylen I; SymTime Study Group . Gender disparities in first medical contact and delay in ST‐elevation myocardial infarction: a prospective multicentre Swedish survey study. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e020211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Udell JA, Koh M, Qiu F, Austin PC, Wijeysundera HC, Bagai A, Yan AT, Goodman SG, Tu JV, Ko DT. Outcomes of women and men with acute coronary syndrome treated with and without percutaneous coronary revascularization. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e004319 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heart Foundation . Women and Heart Disease. 2018. Available at: https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/your-heart/women-and-heart-disease. Accessed August 2018.

- 10. Stub D, Lefkovits J, Brennan AL, Dinh D, Brien R, Duffy SJ, Cox N, Nadurata V, Clark DJ, Andrianopoulos N, Harper R, McNeil J, Reid CM; VCOR Steering Committee . The establishment of the Victorian Cardiac Outcomes Registry (VCOR): monitoring and optimising outcomes for cardiac patients in Victoria. Heart Lung Circ. 2018;27:451–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cox N, Brennan A, Dinh D, Brien R, Cowie K, Stub D, Reid CM, Lefkovits J. Implementing sustainable data collection for a cardiac outcomes registry in an Australian public hospital. Heart Lung Circ. 2018;27:464–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Zijlstra F, van‘t Hof AW, Hoorntje JC, Gosselink AT, Dambrink JH, de Boer MJ; ZWOLLE Myocardial Infarction Study Group . Symptom‐onset‐to‐balloon time and mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated by primary angioplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:991–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Menees DS, Peterson ED, Wang Y, Curtis JP, Messenger JC, Rumsfeld JS, Gurm HS. Door‐to‐balloon time and mortality among patients undergoing primary PCI. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:901–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bugiardini R, Ricci B, Cenko E, Vasiljevic Z, Kedev S, Davidovic G, Zdravkovic M, Milicic D, Dilic M, Manfrini O, Koller A, Badimon L. Delayed care and mortality among women and men with myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e005968 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.005968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Meyer MR, Bernheim AM, Kurz DJ, O'Sullivan CJ, Tuller D, Zbinden R, Rosemann T, Eberli FR. Gender differences in patient and system delay for primary percutaneous coronary intervention: current trends in a Swiss ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction population. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2019;8(3):283–290. 2048872618810410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Diercks DB, Owen KP, Kontos MC, Blomkalns A, Chen AY, Miller C, Wiviott S, Peterson ED. Gender differences in time to presentation for myocardial infarction before and after a national women's cardiovascular awareness campaign: a temporal analysis from the Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress ADverse Outcomes with Early Implementation (CRUSADE) and the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network‐Get with the Guidelines (NCDR ACTION Registry‐GWTG). Am Heart J. 2010;160:80–87.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hansen KW, Soerensen R, Madsen M, Madsen JK, Jensen JS, von Kappelgaard LM, Mortensen PE, Galatius S. Developments in the invasive diagnostic‐therapeutic cascade of women and men with acute coronary syndromes from 2005 to 2011: a nationwide cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kirchberger I, Heier M, Kuch B, Wende R, Meisinger C. Sex differences in patient‐reported symptoms associated with myocardial infarction (from the population‐based MONICA/KORA Myocardial Infarction Registry). Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:1585–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lichtman JH, Leifheit EC, Safdar B, Bao H, Krumholz HM, Lorenze NP, Daneshvar M, Spertus JA, D'Onofrio G. Sex differences in the presentation and perception of symptoms among young patients with myocardial infarction: evidence from the VIRGO Study (Variation in Recovery: role of Gender on Outcomes of Young AMI Patients). Circulation. 2018;137:781–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Benamer H, Bataille S, Tafflet M, Jabre P, Dupas F, Laborne FX, Lapostolle F, Lefort H, Juliard JM, Letarnec JY, Lamhaut L, Lebail G, Boche T, Loyeau A, Caussin C, Mapouata M, Karam N, Jouven X, Spaulding C, Lambert Y. Longer pre‐hospital delays and higher mortality in women with STEMI: the e‐MUST Registry. EuroIntervention. 2016;12:e542–e549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kuhn L, Page K, Rolley JX, Worrall‐Carter L. Effect of patient sex on triage for ischaemic heart disease and treatment onset times: a retrospective analysis of Australian emergency department data. Int Emerg Nurs. 2014;22:88–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Choi K, Shofer FS, Mills AM. Sex differences in STEMI activation for patients presenting to the ED 1939. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:1939–1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gupta A, Barrabes JA, Strait K, Bueno H, Porta‐Sanchez A, Acosta‐Velez JG, Lidon RM, Spatz E, Geda M, Dreyer RP, Lorenze N, Lichtman J, D'Onofrio G, Krumholz HM. Sex differences in timeliness of reperfusion in young patients with ST‐segment‐elevation myocardial infarction by initial electrocardiographic characteristics. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e007021 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huded CP, Johnson M, Kravitz K, Menon V, Abdallah M, Gullett TC, Hantz S, Ellis SG, Podolsky SR, Meldon SW, Kralovic DM, Brosovich D, Smith E, Kapadia SR, Khot UN. 4‐step protocol for disparities in STEMI care and outcomes in women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:2122–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lansky AJ, Pietras C, Costa RA, Tsuchiya Y, Brodie BR, Cox DA, Aymong ED, Stuckey TD, Garcia E, Tcheng JE, Mehran R, Negoita M, Fahy M, Cristea E, Turco M, Leon MB, Grines CL, Stone GW. Gender differences in outcomes after primary angioplasty versus primary stenting with and without abciximab for acute myocardial infarction: results of the Controlled Abciximab and Device Investigation to Lower Late Angioplasty Complications (CADILLAC) trial. Circulation. 2005;111:1611–1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kolte D, Khera S, Aronow WS, Mujib M, Palaniswamy C, Sule S, Jain D, Gotsis W, Ahmed A, Frishman WH, Fonarow GC. Trends in incidence, management, and outcomes of cardiogenic shock complicating ST‐elevation myocardial infarction in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000590 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pancholy SB, Shantha GP, Patel T, Cheskin LJ. Sex differences in short‐term and long‐term all‐cause mortality among patients with ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary percutaneous intervention: a meta‐analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1822–1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. EUGenMed Cardiovascular Clinical Study Group , Regitz‐Zagrosek V, Oertelt‐Prigione S, Prescott E, Franconi F, Gerdts E, Foryst‐Ludwig A, Maas AH, Kautzky‐Willer A, Knappe‐Wegner D, Kintscher U, Ladwig KH, Schenck‐Gustafsson K, Stangl V. Gender in cardiovascular diseases: impact on clinical manifestations, management, and outcomes. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Prasad A, Gersh BJ, Mehran R, Brodie BR, Brener SJ, Dizon JM, Lansky AJ, Witzenbichler B, Kornowski R, Guagliumi G, Dudek D, Stone GW. Effect of ischemia duration and door‐to‐balloon time on myocardial perfusion in ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction: an analysis from HORIZONS‐AMI Trial (Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:1966–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Valgimigli M, Gagnor A, Calabro P, Frigoli E, Leonardi S, Zaro T, Rubartelli P, Briguori C, Ando G, Repetto A, Limbruno U, Cortese B, Sganzerla P, Lupi A, Galli M, Colangelo S, Ierna S, Ausiello A, Presbitero P, Sardella G, Varbella F, Esposito G, Santarelli A, Tresoldi S, Nazzaro M, Zingarelli A, de Cesare N, Rigattieri S, Tosi P, Palmieri C, Brugaletta S, Rao SV, Heg D, Rothenbuhler M, Vranckx P, Juni P; MATRIX Investigators . Radial versus femoral access in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing invasive management: a randomised multicentre trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2465–2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gargiulo G, Ariotti S, Vranckx P, Leonardi S, Frigoli E, Ciociano N, Tumscitz C, Tomassini F, Calabro P, Garducci S, Crimi G, Ando G, Ferrario M, Limbruno U, Cortese B, Sganzerla P, Lupi A, Russo F, Garbo R, Ausiello A, Zavalloni D, Sardella G, Esposito G, Santarelli A, Tresoldi S, Nazzaro MS, Zingarelli A, Petronio AS, Windecker S, da Costa BR, Valgimigli M. Impact of sex on comparative outcomes of radial versus femoral access in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing invasive management: data from the Randomized MATRIX‐Access trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:36–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Navarese EP, Gurbel PA, Andreotti F, Tantry U, Jeong YH, Kozinski M, Engstrom T, Di Pasquale G, Kochman W, Ardissino D, Kedhi E, Stone GW, Kubica J. Optimal timing of coronary invasive strategy in non‐ST‐segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:261–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Swahn E, Alfredsson J, Afzal R, Budaj A, Chrolavicius S, Fox K, Jolly S, Mehta SR, de Winter R, Yusuf S. Early invasive compared with a selective invasive strategy in women with non‐ST‐elevation acute coronary syndromes: a substudy of the OASIS 5 trial and a meta‐analysis of previous randomized trials. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. De Carlo M, Morici N, Savonitto S, Grassia V, Sbarzaglia P, Tamburrini P, Cavallini C, Galvani M, Ortolani P, De Servi S, Petronio AS. Sex‐related outcomes in elderly patients presenting with non‐ST‐segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: insights from the Italian Elderly ACS study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:791–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Radovanovic D, Erne P, Urban P, Bertel O, Rickli H, Gaspoz JM; AMIS Plus Investigators . Gender differences in management and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes: results on 20,290 patients from the AMIS Plus Registry. Heart. 2007;93:1369–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]