Abstract

Background

Telomere length has been inversely associated with cardiovascular disease in adulthood, but its relationship to preclinical cardiovascular phenotypes across the life course remains unclear. We investigated associations of telomere length with vascular structure and function in children and midlife adults.

Methods and Results

Population‐based cross‐sectional CheckPoint (Child Health CheckPoint) study of 11‐ to 12‐year‐old children and their parents, nested within the LSAC (Longitudinal Study of Australian Children). Telomere length (telomeric genomic DNA [T]/β‐globin single‐copy gene [S] [T/S ratio]) was measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction from blood‐derived genomic DNA. Vascular structure was assessed by carotid intima‐media thickness, and vascular function was assessed by carotid‐femoral pulse‐wave velocity and carotid elasticity. Mean (SD) T/S ratio was 1.09 (0.55) in children (n=1206; 51% girls) and 0.81 (0.38) in adults (n=1343; 87% women). Linear regression models, adjusted for potential confounders, revealed no evidence of an association between T/S ratio and carotid intima‐media thickness, carotid‐femoral pulse‐wave velocity, or carotid elasticity in children. In adults, longer telomeres were associated with greater carotid elasticity (0.14% per 10–mm Hg higher per unit of T/S ratio; 95% CI, 0.04%–0.2%; P=0.007), but not carotid intima‐media thickness (−0.9 μm; 95% CI, −14 to 13 μm; P=0.9) or carotid‐femoral pulse‐wave velocity (−0.10 m/s; 95% CI, −0.3 to 0.07 m/s; P=0.2). In logistic regression analysis, telomere length did not predict poorer vascular measures at either age.

Conclusions

In midlife adults, but not children, there was some evidence that telomere length was associated with vascular elasticity but not thickness. Associations between telomere length and cardiovascular phenotypes may become more evident in later life, with advancing pathological changes.

Keywords: aging, arterial stiffness, atherosclerosis, carotid intima‐media thickness, CheckPoint (Child Health CheckPoint) study, LSAC (Longitudinal Study of Australian Children), pulse‐wave velocity

Subject Categories: Biomarkers, Vascular Biology, Aging, Epidemiology, Cardiovascular Disease

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

This is the first study to examine the relationship between telomere length and vascular structure and function in a population‐based cohort of children and adults.

In midlife adults, but not children, there was some evidence that telomere length was associated with vascular elasticity.

The novel small association between longer telomere length and higher carotid elasticity in adults is interesting; however, the strength of the association could equally be caused by chance and, hence, requires replication.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

The clinical utility of cross‐sectional telomere length assessment for cardiovascular disease risk in healthy populations of children or midlife adults is limited.

Future studies should consider longitudinal associations of telomere length with vascular phenotypes and cardiovascular events.

Introduction

Given the global burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD), considerable efforts are under way to understand the underlying cause and to identify potential biomarkers predictive of risk.1 Cell senescence may play an important role in the progression of CVD, although the upstream drivers of CVD‐associated cell death remain to be fully elucidated. One well‐studied pathway to cellular senescence is mediated via telomere shortening. Telomeres are nucleoprotein structures that cap the ends of linear chromosomes. Their shortening represents a molecular mechanism of biological aging2 and occurs because of the general inability of cells to replicate the ends of linear DNA in the absence of telomerase. At a critical length, the DNA damage response drives cell senescence, resulting in inhibited tissue repair capacity and function.

Considerable evidence has linked shorter telomeres with greater risk of all‐cause mortality,3 cancer,4 infectious disease,5 and CVD.6, 7 Notably, a meta‐analysis of 43 725 adults (mean age, 60 years) showed that those with the shortest telomeres in blood had a 30% to 83% higher risk of coronary artery disease relative to those with the longest telomeres.6 Recent studies in adults have shown accelerated telomere shortening in blood cells from patients with atherosclerosis.8, 9 Few studies have explored this relationship in relatively healthy populations of younger individuals, despite the fact that the pathways to cardiometabolic ill health in adulthood begin much earlier in life.1 Telomere‐linked cell senescence may be on the mechanistic pathway to poor cardiovascular health, or it may represent a critical “tipping point” in the life course when overt CVD emerges.

Noninvasive measures of vascular phenotypes enable assessment of cardiovascular structure and function in the large arteries. Ultrasound and tonometry of the carotid artery can capture carotid intima‐media thickness (IMT),10, 11 carotid‐femoral pulse‐wave velocity (PWV), and carotid elasticity.12, 13, 14 Carotid IMT is a validated structural marker of subclinical atherosclerosis and correlates with total atherosclerotic burden in adults.15 Faster carotid‐femoral PWV and reduced carotid elasticity are functional measures of arterial stiffness14 linked to higher risk of cardiovascular events.16 Thicker carotid IMT has previously been associated with shorter telomeres in clinical samples of older adults.17, 18 However, recent studies of healthy adults in late life showed that telomere length was not associated with carotid IMT19 or with carotid atherosclerosis.20 Functional measures have also been linked with shortened telomeres in later‐life adults.21, 22

Although telomere length may be a potential mechanism underlying CVD across the life course, studies are conflicting6 and little is known of the relationship in younger adults or children. It may be that telomere length is associated with vascular function earlier than structural phenotypes.23 Thus, exploring the relationship of telomere length with functional and structural phenotypes across the life course could enhance our understanding of the role of telomere length‐driven cell senescence in the pathogenesis of CVD. We aimed to assess the associations of telomere length with measures of vascular structure and function in a population‐based cross‐sectional study of children and their parents.

Materials and Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Study Design and Participants

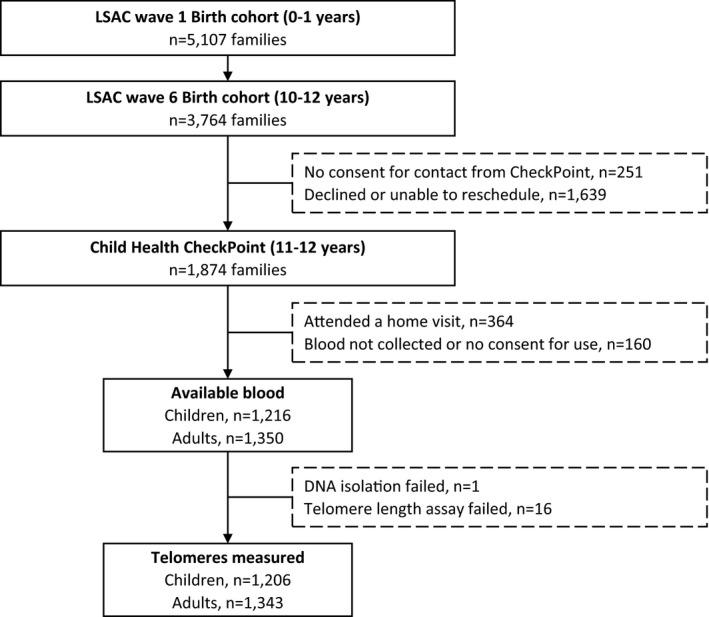

The LSAC (Longitudinal Study of Australian Children) recruited a nationally representative birth cohort in 2004 (n=5107). Participants have been followed up at 7 biennial waves spanning birth to 13 years. The CheckPoint (Child Health CheckPoint) study was an additional physical health and biomarker wave for the birth cohort, nested between LSAC's sixth and seventh waves. During the LSAC wave 6 assessment in 2014, interviewers obtained written consent from 3513 families (93% of the 3764 seen) to be contacted to participate in the upcoming CheckPoint study. Ultimately, 1874 adult‐child pairs (50%) took part. Most nonparticipation (60%) was caused by inability to attend or to reschedule a visit during the short period CheckPoint study was in each location. Details of the LSAC and CheckPoint study design and recruitment have been previously described,24, 25, 26, 27 and the Figure shows the flow through the study.

Figure 1.

LSAC (Longitudinal Study of Australian Children) and CheckPoint (Child Health CheckPoint) study participant flow.

Data collection ran from February 2015 to March 2016. The CheckPoint study Assessment Center operated sequentially across Australia in major cities (3.5 hours, main center) and regional centers (2.5 hours, minicenter), with home visits offered to those unable to attend a center. Children and their attending parent rotated through a series of 15‐minute stations, in which different aspects of health were assessed and biological samples were collected, including venous blood. A trained researcher undertook cardiovascular measures while medically trained researchers or phlebotomists collected venous blood. Samples were processed and cryopreserved within 2 hours on site. For the first 2 months, this included blood clots from plasma tubes; for logistic reasons, clots were then discontinued and replaced with a whole blood sample for the remaining centers. As each assessment center closed, samples were transported to the Murdoch Children's Research Institute in Melbourne, Australia, where they remain cryopreserved until depletion. The logistics and specified requirements of this large, national, government‐owned population‐based cohort precluded any participants attending repeated sessions. However, all values for all participants in both age groups are based on repeated measurements within the same session, as are the interobserver and intraobserver ratings for the observer‐dependent measurements (carotid IMT and waveform quality ratings). Previous studies have confirmed similar repeatability between children and adults,28, 29 and between sessions separated by hours to weeks.30

The study was approved by the Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (33225D) and the Australian Institute of Family Studies Ethics Committee (14‐26). The attending parents provided written informed consent for themselves and their child before participation, and the child provided assent.

DNA Isolation and Telomere Length Measurement

Genomic DNA was isolated from available blood using the QIAamp 96 DNA Blood Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, the Netherlands). Purity and integrity was confirmed using the NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Middleton, WI), the Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and gel electrophoresis. Telomere length was measured with the quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction method, originally described by Cawthon.31 This method measures the amount of telomeric genomic DNA (T)/β‐globin single‐copy gene (S) (T/S ratio) for each participant. The mean intra‐assay variability between “T” and “S” quadruplicates used in the calculation of the T/S ratio was 1.7% (SD, 0.3%; range, 0.9%–2.6%). The interassay variability between plates was 1.7% (SD, 1.4%; range, 0.3%–6.2%). Further details on the telomere length calculation (Table S1), plate conditions, and constituents are described in Data S1 and in the Standard Operating Procedure on the CheckPoint study's website.32, 33

Carotid IMT and Carotid Elasticity

Carotid IMT and elasticity were measured using standardized protocols via ultrasound (Vivid i BT06 with 10‐MHz linear array probe; GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK).10, 11 Ultrasounds were performed in supine position with head turned 45° to the left. The ultrasound probe was applied to the right side of the neck at ≈45° to the midline with concurrent 3‐lead ECG trace. The duration of the captured real‐time B‐mode ultrasound cine loops was 10 cardiac cycles.

All images were reviewed for quality to select optimal loops comprising a clear near and far wall intima‐media, clear lumen, straight vessel, presence of the carotid bulb, and an ECG trace. The best‐quality 5 to 7 cardiac cycle section of the loops was trimmed and extracted. These loops were further processed using Carotid Analyzer (Medical Imaging Applications, Coralville, IA). Raters calibrated the images using ultrasound image markers. Maximum carotid IMT values were used in analyses, which refer to the 3 to 5 frame average of the thickest point of carotid IMT measurement over the highest quality 5‐ to 10‐mm section from the carotid bulb. After algorithmic detection of the intima‐media interface over the entire cine‐loop, frames were manually adjusted as needed or rejected if the intima‐media interface was unclear or blurred. The intraobserver variability for the maximum carotid IMT values was 4.9% (95% CI, 4.6%–5.2%), and the interobserver variability was 6.2% (95% CI, 5.2%–7.2%). Further details are described elsewhere.25, 34

Carotid elasticity was calculated from carotid artery images and expressed as a percentage change in intima‐intima lumen diameter (measured from ultrasound) per change in pulse pressure (measured from SphygmoCor), as previously described (Table S1).13 Intima‐intima lumen diameter measurement was automated using Carotid Analyzer and, thus, was rater independent; it was calculated by measuring the average intima‐intima distance (subtracting near and far wall IMT measurements) on each of the 3 to 5 still frames used to calculate maximum carotid IMT. Intraobserver and interobserver variability values for maximum lumen diameter were 1.3% (95% CI, 1.2%–1.4%) and 1.6% (95% CI, 1.4%–1.9%), respectively; and values for minimum lumen diameter were 1.2% (95% CI, 1.1%–1.3%) and 1.5% (95% CI, 1.2%–1.7%), respectively. Further details are in Data S1 and prior publications.25, 34

Carotid‐Femoral PWV and Blood Pressure

Carotid‐femoral PWV and blood pressure were measured using tonometry via SphygmoCor XCEL (AtCor Medical, West Ryde, Australia), as previously described.14 Carotid‐femoral PWV was determined by detecting waveforms simultaneously by a hand‐held tonometer at the carotid pulse and a cuff placed on the proximal thigh, over a 10‐second period. This was completed 3 times in the supine position. The distance traveled by waveforms was measured with a tape measure from the carotid pulse to the suprasternal notch, from the suprasternal notch to the right femoral pulse, and from the femoral pulse to the top of the thigh cuff. The mean of at least 2 valid carotid‐femoral PWV measurements (in m/s) was used in analyses. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure values were recorded at the brachial artery, 3 times, 1 minute apart, with either a 23‐ to 33‐cm or a 31‐ to 40‐cm cuff, depending on arm size. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure values were included if participants had at least 2 valid measurements. Further details of these measures are described elsewhere.25, 35

At the time of assessment, waveforms were assessed using the in‐built quality control software in the SphygmoCor XCEL. After study completion, waveforms were further reviewed by 2 trained analysts and were excluded if they did not meet quality control standards. To assess interrater reliability, 112 individually recorded waves from a random sample of 40 participants (20 children and 20 adults) from the CheckPoint study database were presented blindly to 2 analysts for review. Pulse wave quality ratings given by each analyst (poor, adequate, or good) were compared by calculating the proportion of positive agreement between analysts. Most sample waveforms were of good quality, and none were of poor quality. The overall correlation between analysts was high (r=0.99). Automated measurement of carotid‐femoral PWV by SphygmoCor is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, is extensively standardized across large general populations,22, 36, 37 and is validated against other well‐validated tonometry‐based methods,38, 39 as per the ARTERY (Association for Research into Arterial Structure and Physiology) PWV validation guidelines.40 Published values for interobserver and intraobserver carotid‐femoral PWV variability are 0.30 m/s (SD, 1.25 m/s) and 0.07 m/s (SD, 1.17 m/s), respectively.41 Further details are in Data S1 and are described elsewhere.25, 35

Potential Confounders

Several variables were considered a priori as potential confounders, including body mass index (BMI; kg/m2),42 socioeconomic status,43 and smoking.44 Each of these variables has consistently been associated with telomere length, as well as being commonly known risk factors for cardiovascular health. BMI was calculated from height (standard portable stadiometer; IP0955; Invicta, Leicester, UK) and weight (InBody230 bioelectrical impedance analysis scale; Biospace Co Ltd Seoul, South Korea). For children, an age‐ and sex‐adjusted BMI z score was calculated using the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth reference charts.45 As a measure of neighborhood socioeconomic status, we used the Socio‐Economic Indexes for Areas Index of Relative Disadvantage score, which is based on the postcode of domicile of the participating family. This is a standardized score by geographic area, compiled from 2011 Australian Census data to numerically summarize the social and economic conditions of Australian neighborhoods (national mean of 1000 and SD of 100, where higher values represent less disadvantage). Parental current smoking behavior and cigarettes smoked per day were self‐reported at LSAC wave 6. Preexisting conditions were self‐reported (yes/no) by questionnaire at the CheckPoint study assessment, including diabetes mellitus status, heart conditions, hypertension medication, and pacemakers. Further details of these sample measures are described elsewhere.25

Other Covariates

Other covariates traditionally associated with cardiovascular outcomes were measured using the Nightingale nuclear magnetic resonance metabolomics platform (Helsinki, Finland) from blood serum. These included lipids (total cholesterol, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides), glucose, and the inflammation marker of glycoprotein acetyls. Further details of this platform and method are extensively described elsewhere.46

Statistical Analysis

Stata 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) was used for all analyses. Continuous variables are presented as means and SD, whereas dichotomous variables are presented as percentages.

Associations of telomere length with vascular measures were examined by linear and logistic regression models, in children and adults separately. Assumptions for linear regression were examined using histograms and scatterplots, and they showed no discernible outliers and minimal right skewing for child's and adult's telomere length. For aim 1, linear regression models fitted continuous telomere length as the independent variable and continuous data on vascular measures as dependent variables in separate models. For aim 2, logistic regression models fitted continuous telomere length as the independent variable and elevated carotid IMT, carotid‐femoral PWV, and reduced carotid elasticity as the dependent variables in separate models. Elevated carotid IMT and elevated carotid‐femoral PWV were defined internally as >75th percentile for the sample. Reduced carotid elasticity was defined internally as <25th percentile.

For both aims, model 1 included adjustments for the potential lifelong confounders of sex and age, as well as for sample type (ie, whole blood or blood clot) to account for any effects of the early change in the sample collection protocol from blood clots to whole blood. Adjusted analyses included the covariates as independent variables. Model 2 additionally included adjustments for the additional potential confounders of BMI and Socio‐Economic Indexes for Areas Index of Relative Disadvantage score, plus smoking status, for adults. In model 3, we further adjusted for systolic blood pressure, lipids, glucose, and glycoprotein acetyls. Finally, we conducted sensitivity analysis that did the following: (1) further adjusted for preexisting conditions, (2) adjusted for mean arterial pressure or diastolic blood pressure in place of systolic blood pressure, and (3) stratified by, rather than adjusted for, sample type. Sensitivity analyses showed similar results to those presented below (data not shown; available on request).

Results

A total of 1874 parent‐child dyads participated in the CheckPoint study (Figure). As venous blood was not collected at home visits (n=364 dyads), these participants were not included in the current analysis. Venous blood (whole blood or blood clot) was available for 1216 children and 1350 adults. Telomere length data were generated for 1206 children (99.2%) and 1343 adults (99.5%).

Sample Characteristics

Participant characteristics are displayed in Table 1. Children and adults were, on average, aged 11 years (SD, 0.5 years) and 44 years (SD, 5.1 years), respectively. Adults were predominantly mothers (n=1168; 87%), whereas there were approximately equal numbers of boys and girls. Participants came from slightly less disadvantaged and more homogeneous areas compared with the national average (mean Socio‐Economic Indexes for Areas Index of Relative Disadvantage score, 1026 [SD, 61] versus 1000 [SD, 100]). Child and adult BMI scores were similar to those of the current Australian population, as recorded by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, with ≈1 in 4 children and 2 in 3 adults overweight or obese.47 Compared with the general Australian population rates for similar age ranges, adults’ self‐report of diabetes mellitus (2.4% versus 4%) and being a current smoker (8% versus 16%) were lower47 but CVD (2.2% versus 2.5%) was comparable.47

Table 1.

Summary Characteristics of Children and Adults

| Participant Characteristic | Children | Adults |

|---|---|---|

| Total No. | 1206 | 1343 |

| Age, y | 11 (0.5) | 44 (5.1) |

| Female sex, % | 51 | 87 |

| Height, cm | 154 (8) | 167 (8) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 19 (3) | 28 (6) |

| Body mass index z score | 0.3 (1) | ··· |

| Disadvantage score | 1026 (62) | 1026 (61) |

| Current smoking, % | ··· | 8.2 |

| Cigarettes smoked per day | ··· | 2.6 (0.14) |

| Preexisting conditions, % | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.1 | 2.4 |

| Heart condition | ··· | 2.2 |

| Hypertension medication | ··· | 5.1 |

| Pacemakers | ··· | 0.1 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 108 (8) | 120 (13) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 63 (6) | 74 (9) |

| Lumen diameter, mm | 5.9 (0.5) | 5.8 (0.6) |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 54 (10) | 56 (14) |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 25 (6) | 30 (8) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 73 (12) | 86 (16) |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 105 (49) | 132 (75) |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 89 (14) | 88 (19) |

| Glycoprotein acetylation, mmol/L | 0.99 (0.13) | 1.04 (0.17) |

| Telomere length (T/S ratio) | 1.09 (0.55) | 0.81 (0.38) |

| Vascular outcomes | ||

| Carotid intima‐media thickness, μm | 580 (46) | 663 (97) |

| Carotid‐femoral pulse wave velocity, m/s | 4.4 (0.5) | 7.0 (1.1) |

| Carotid elasticity, % per 10‐mm Hg | 4.8 (0.9) | 2.4 (0.6) |

Data are presented as mean (SD) or percentage. HDL indicates high‐density lipoprotein; LDL, low‐density lipoprotein; T/S ratio, telomeric genomic DNA (T)/β‐globin single‐copy gene (S).

Children had longer telomeres (higher T/S ratio, 1.09; SD, 0.55) than adults (0.81; SD, 0.38).33 Adults, on average, had thicker carotid IMT than children (663 [SD, 97] μm versus 580 [SD, 46] μm) and stiffer vessels, as shown in faster carotid‐femoral PWV (7.0 [SD, 1.1] m/s versus 4.4 [SD, 0.5] m/s) and lower carotid elasticity (2.4% [SD, 0.6%] versus 4.8% [SD, 0.9%] per 10‐mm Hg). Further details of the distributions of vascular phenotypes are in Figure S1 and were previously described.34, 35 Adults with self‐reported diabetes mellitus and hypertension medication use had thicker carotid IMT, faster carotid‐femoral PWV, and lower carotid elasticity (Table S2). Vascular phenotypes were similar in current smokers and nonsmokers, noting that this may be limited by lack of smoking history. Telomere length was not related with diabetes mellitus, current smoking, and hypertension medication in adults (Table S3). Higher blood pressure was associated with longer telomeres in adults, but not in children (Table S4).

Association of Telomere Length With Carotid IMT, Carotid‐Femoral PWV, and Carotid Elasticity

In linear regression models adjusted for age, sex, and sample type, children's T/S ratio showed little association with vascular measures (Table 2; model 1). Similarly, adult T/S ratio showed little association with carotid IMT or carotid‐femoral PWV (Table 2; model 1). However, in adults, longer telomeres were associated with greater carotid elasticity (0.14% per 10‐mm Hg higher for each additional unit of T/S ratio; 95% CI, 0.04%–0.2%). This is equivalent to an effect size of 0.09 SDs higher carotid elasticity for each SD increase in T/S ratio. This association persisted after adjustments for sex, age, sample type, BMI, Socio‐Economic Indexes for Areas Index of Relative Disadvantage score, and smoking status (0.13% per 10‐mm Hg; 95% CI, 0.05%–0.20%; Table 2; model 2), as well as for systolic blood pressure, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, and glycoprotein acetyls (0.09% per 10‐mm Hg; 95% CI, 0.003%–0.18%; Table 2; model 3).

Table 2.

Association of Telomere Length With Carotid IMT, Carotid‐Femoral PWV, and Carotid Elasticity, in Children and Adults

| Outcome | Children | Adults | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Coefficient (95% CI) | R 2 | P Value | No. | Coefficient (95% CI) | R 2 | P Value | |

| Model 1a | ||||||||

| Carotid IMT, μm | 1193 | 4.11 (−1.21 to 9.4) | 0.04 | 0.13 | 1203 | −0.85 (−14.31 to 12.61) | 0.16 | 0.90 |

| Carotid‐femoral PWV, m/s | 1167 | −0.01 (−0.07 to 0.06) | 0.06 | 0.86 | 1110 | −0.10 (−0.27 to 0.07) | 0.10 | 0.23 |

| Carotid elasticity, % per 10‐mm Hg | 1083 | −0.04 (−0.15 to 0.06) | 0.01 | 0.42 | 1040 | 0.14 (0.04 to 0.24) | 0.12 | 0.007 |

| Model 2b | ||||||||

| Carotid IMT, μm | 1192 | 4.67 (−0.64 to 9.99) | 0.05 | 0.09 | 1198 | 0.46 (−12.71 to 13.64) | 0.20 | 0.95 |

| Carotid‐femoral PWV, m/s | 1166 | 0.01 (−0.05 to 0.07) | 0.13 | 0.68 | 1106 | −0.12 (−0.28 to 0.04) | 0.24 | 0.13 |

| Carotid elasticity, % per 10‐mm Hg | 1082 | −0.06 (−0.17 to 0.05) | 0.04 | 0.26 | 1035 | 0.13 (0.04 to 0.22) | 0.26 | 0.006 |

| Model 3c | ||||||||

| Carotid IMT, μm | 1082 | 4.89 (−0.60 to 10.37) | 0.07 | 0.08 | 1082 | 1.17 (−12.60 to 14.94) | 0.25 | 0.87 |

| Carotid‐femoral PWV, m/s | 1070 | 0.02 (−0.04 to 0.08) | 0.16 | 0.57 | 1031 | −0.09 (−0.23 to 0.06) | 0.40 | 0.24 |

| Carotid elasticity, % per 10‐mm Hg | 1037 | −0.09 (−0.19 to 0.02) | 0.15 | 0.11 | 1003 | 0.09 (0.003 to 0.18) | 0.36 | 0.04 |

IMT indicates intima‐media thickness; PWV, pulse‐wave velocity; R 2, value for the linear regression model.

Model 1 was adjusted for sex, age, and sample type.

Model 2 was additionally adjusted for body mass index, Socio‐Economic Indexes for Areas Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage score, plus smoking status for adults.

Model 3 was additionally adjusted for brachial systolic blood pressure, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, and glycoprotein acetylation.

In both adults and children, adjusted logistic regression models showed little evidence of a difference in the odds of elevated carotid IMT, elevated carotid‐femoral PWV, or reduced carotid elasticity for each unit higher T/S ratio (Table 3).

Table 3.

Odds Ratio for Elevated Carotid IMT, Elevated Carotid‐Femoral PWV, and Reduced Carotid Elasticity for 1 Unit Higher T/S Ratio, in Children and Adults

| Outcome | Children | Adults | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | No. | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Model 1a | ||||||

| Elevated carotid IMT | 1193 | 1.23 (0.94–1.61) | 0.13 | 1203 | 0.94 (0.65–1.37) | 0.77 |

| Elevated carotid‐femoral PWV | 1167 | 0.82 (0.60–1.13) | 0.23 | 1110 | 0.88 (0.59–1.30) | 0.56 |

| Reduced carotid elasticitya | 1083 | 0.99 (0.73–1.32) | 0.92 | 1040 | 0.84 (0.55–1.30) | 0.44 |

| Model 2b | ||||||

| Elevated carotid IMT | 1192 | 1.27 (0.97–1.66) | 0.08 | 1198 | 0.98 (0.67–1.44) | 0.92 |

| Elevated carotid‐femoral PWV | 1166 | 0.88 (0.63–1.23) | 0.47 | 1106 | 0.83 (0.54–1.28) | 0.40 |

| Reduced carotid elasticity | 1082 | 1.02 (0.76–1.38) | 0.91 | 1035 | 0.83 (0.52–1.32) | 0.42 |

| Model 3c | ||||||

| Elevated carotid IMT | 1082 | 1.26 (0.95–1.68) | 0.11 | 1082 | 1.03 (0.66–1.61) | 0.89 |

| Elevated carotid‐femoral PWV | 1070 | 0.97 (0.68–1.38) | 0.86 | 1031 | 0.73 (0.43–1.24) | 0.25 |

| Reduced carotid elasticity | 1037 | 1.16 (0.84–1.58) | 0.37 | 1033 | 1.03 (0.61–1.74) | 0.92 |

Elevated carotid IMT defined as >75th percentile, elevated carotid‐femoral PWV defined as >75th percentile, and reduced carotid elasticity defined as <25th percentile. IMT indicates intima‐media thickness; PWV, pulse‐wave velocity; T/S ratio, telomeric genomic DNA (T)/β‐globin single‐copy gene (S).

Model 1 was adjusted for sex, age, and sample type.

Model 2 was additionally adjusted for body mass index, Socio‐Economic Indexes for Areas Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage score, plus smoking status for adults.

Model 3 was additionally adjusted for brachial systolic blood pressure, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, and glycoprotein acetylation.

Discussion

Main Findings

In the present study, we hypothesized that telomere attrition is an upstream event of cardiometabolic disease and, as such, evidence for shortened telomeres will be present in mid‐aged adults and children in association with preclinical phenotypes of poorer cardiovascular health. Furthermore, given the progressive nature of the proposed association, we predicted that the strength of association between telomere length and phenotypes will be stronger in adults relative to their children. We tested this in a population‐based cohort of children and mid‐life adults and found no convincing evidence of associations between shorter telomeres and adverse vascular phenotypes at either age, other than a small association between longer telomere length and increased carotid elasticity in adults.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of our study include the objective examination of carotid IMT, carotid‐femoral PWV, and carotid elasticity with high reliability and the T/S measurements showing low replicate variation. We are confident in interpreting the child and adult findings within the same study because they were assessed at the same time point with the same protocols, equipment, and staff. For telomere length, we used a quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction method that correlates strongly with the gold standard terminal restriction fragment analysis.31 However, although well suited for large epidemiological studies, this method does not quantify absolute, chromosome‐specific, or vascular tissue‐specific telomere length. Also, the capacity of telomere length derived from blood as a surrogate for telomere length within the vasculature itself is uncertain; however, there is evidence that telomere length is highly conserved between tissues.48, 49 Differential uptake in LSAC and attrition in CheckPoint study led to our sample including few fathers and few less disadvantaged families than in the general Australian population. Thus, if such children and adults had both shorter telomeres and poorer vascular outcomes, this could have altered estimates and/or their precision. Finally, the cross‐sectional design precluded conclusions about temporal associations.

Interpretation in Light of Other Studies

Telomere length, vascular structure, and atherosclerosis

We found little evidence of an association between telomere length and carotid IMT. This is consistent with several prior reports showing no or only marginal associations.17, 19, 20, 50, 51, 52 For example, in healthy adults, telomere length was not independently associated with carotid IMT19 (n=2509; age range, 35–55 years) and atherosclerosis in the carotid arteries (n=1459; age range, 40–54 years).20 Together, these studies suggest that associations between telomere length and vascular structure appear primarily later in adulthood. Moreover, there is evidence that shortened telomere length is more reliably associated with patients with CVD. For example, shorter telomere length has been observed in aortic tissues with atherosclerotic lesions, compared with tissues without atherosclerotic lesions;8 and in another study, telomere length was associated with advanced‐state, but not with early‐stage, atherosclerosis.51 Telomere shortening might play a role late in the pathogenesis of CVD, in late adulthood when the effects of cumulative burden over the life course begin to manifest. This hypothesis would be consistent with current knowledge, in which the cellular senescence induced by the aging process is known to trigger the progressive deterioration of vascular functionality with age.53

Our findings also align with evidence that shortened telomere length is associated with vascular phenotypes in those with greater CVD risk6 (eg, in elderly populations; mean age, 74.2 years; SD, 5.2 years),17 diabetic subjects,9, 54 and obese men.50 Interestingly, a recent meta‐analysis of 5566 patients with coronary artery disease found an overall higher risk for coronary artery disease in older subjects (≥70 years), compared with younger subjects (<70 years; relative risk, 1.9 versus 1.5), with respect to individuals in the shortest telomere tertile compared with those in the longest telomere tertile.

Telomere length, vascular function, and arterial stiffness

There was little evidence of an association between telomere length and carotid‐femoral PWV in children or adults. Several recent studies have reported an association between shorter telomeres and faster carotid‐femoral PWV, but most have been in older adults (>50 years), were limited by modest sample sizes (range, 49–303 individuals),21, 37, 54 and were predominately in men.21, 55 For example, Benetos et al showed that shorter telomere length was significantly associated with faster carotid‐femoral PWV in men (n=120; mean age, 55 years; r=−0.14), but not in women (n=73; mean age, 56 years; r=−0.05).55 Similar results were also found in a study of healthy Chinese men (n=112; mean age, 56 years).21 We cannot tell whether our lack of association between telomere length and carotid‐femoral PWV reflects our preponderance of women or the younger age in our sample. Interestingly, previous findings suggest that age significantly modifies the relationship between telomere length and carotid‐femoral PWV in healthy individuals,22 an effect not observed in our study.

In summary, we report a novel, albeit small, association between telomere length and carotid elasticity in adults, which remained after adjustment for a priori specified confounders. Although speculative at this point, this suggests a possibility that cellular senescence might contribute to vascular function, through the elasticity of the vasculature. One hypothesis might be that the secretory phenotype of senescent vascular cells might promote vascular degeneration through the destabilization of extracellular matrix, elastin, collagen, and smooth muscle,12 thus modifying the elasticity of the carotid artery. However, we suspect that it would also have effects on overall arterial stiffness and, thus, affect carotid‐femoral PWV, which we did not find. This discordance warrants further investigation. We note that although vascular structure and function are considered to be related, they ultimately measure different properties of the arterial tree, both likely affected by risk factors in a nonuniform manner. It has been documented that functional changes precede the development of structural alterations in the vasculature.23

Clinical Implications, Unanswered Questions, and Future Direction

Our findings, if replicated in other settings, question the clinical utility of measuring telomere length in healthy relatively young populations. The magnitude of the cross‐sectional association between telomere length and carotid elasticity observed among adults was small. In addition, the European Society of Hypertension and the European Society of Cardiology noted that a carotid IMT of >900 μm and a carotid‐femoral PWV of >12 m/s are associated with increased CVD risk,56 thresholds not reached by our relatively healthy cohort of children and adults. This suggests that the magnitude of the associated changes is unlikely to represent clinically significant differences on CVD risk, especially in largely healthy populations of children or mid‐life adults. However, telomere length might be of greater clinical relevance at an advanced age or in association with more pronounced vascular pathological features. Moreover, it is possible that such associations could be important longitudinally, such that the rate of telomere attrition, rather than cross‐sectional telomere length per se, may be a more clinically important cardiovascular risk marker. Indeed, in a recent British longitudinal study (baseline n=2611; mean age, 53 years; follow‐up age range, 60–64 years), an association was observed between the rate of telomere attrition and thicker carotid IMT at 60 to 64 years, despite limited cross‐sectional associations.18 Future studies should consider longitudinal evaluation with repeated telomere sampling to assess whether telomere attrition over time is associated with vascular phenotypes and cardiovascular events.

We cannot exclude the possibility that our findings may have arisen by chance, and might be explained by factors beyond the scope of this study, including genetic variation and other unmeasured environmental exposures. The ability of carotid ultrasounds and tonometry to effectively measure meaningful changes in vascular structure and function in healthy individuals is also uncertain. In particular, the predictive value of carotid IMT measurement in children aged 11 to 12 years without CVD risk remains unclear.57

Conclusion

In a healthy cohort of children and mid‐life adults, we report limited evidence that cellular senescence, as measured by telomere length, is associated with vascular structure or function in children or adults. The novel small association between longer telomere length and higher carotid elasticity in adults is interesting, supporting our hypothesis that telomere length may be on the mechanistic pathway toward impaired vascular function; however, the strength of the association could equally be caused by chance and, hence, requires replication. Although telomere length may be important for individuals at intermediate to high CVD risk or those at advanced disease stages, as previously reported, cross‐sectional telomere length assessment appears to have limited clinical value for CVD risk in healthy populations, particularly at younger ages. The interaction between telomere dynamics and vascular phenotypes across the life course is multifaceted, with contributions from genetic variation and environmental exposures. Further longitudinal investigations, with repeated telomere and vascular phenotypic sampling, are warranted.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia (Project Grants 1041352 and 1109355), The Royal Children's Hospital Foundation (2014‐241), the Murdoch Children's Research Institute (MCRI), The University of Melbourne, the National Heart Foundation of Australia (100660), and Financial Markets Foundation for Children (2014‐055 and 2016‐310). The MCRI administered the grants for the study and provided infrastructural support (information technology and biospecimen management), but played no role in the conduct or analysis of the trial. Research at the MCRI is supported by the Victorian Government's Operational Infrastructure Support Program. Nguyen was supported by an NHMRC Postgraduate Scholarship (1115167). Saffery was supported by an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (1045161). Ranganathan was supported by an MCRI Clinician Scientist Award. Lycett was supported by an NHMRC Early Career Fellowship (1091124) and a National Heart Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship (101239). Grobler and Dwyer reported no sources of funding. Juonala was supported by the Federal Research Grant of Finland to Turku University Hospital and the Juho Vainio Foundation. Burgner was supported by an NHMRC Fellowship (1064629) and an Honorary Future Leader Fellowship of the National Heart Foundation of Australia (100369). Wake was supported by an NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship (1046518) and Cure Kids New Zealand. The funding bodies had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Data S1. Supplemental methods.

Table S1. Equations for the Calculation of (I, II and III) Telomere Length and (IV) Carotid Elasticity

Table S2. Summary of Adults’ Vascular Outcomes for Diabetics, Current Smokers and Hypertension

Table S3. Summary of Adult T/S Ratios for Diabetics, Hypertension Medication Users

Table S4. Association of Brachial Systolic Blood Pressure (Exposure) With Telomere Length (Separately Outcome), in Children and Adults

Figure S1. Children's (green, solid) and adults’ (blue, dash) distribution of (I) carotid intima‐media thickness, (II) carotid‐femoral pulse wave velocity, (III) carotid elasticity and (IV) telomere length.

Acknowledgments

This article uses data from the LSAC (Longitudinal Study of Australian Children). The study is conducted in partnership between the Department of Social Services, the Australian Institute of Family Studies, and the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The findings and views reported are those of the authors. We thank the LSAC and CheckPoint (Child Health CheckPoint) study participants, staff, and students for their contributions.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e012707 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012707.)

References

- 1. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Despres JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jimenez MC, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, McGuire DK, Mohler ER III, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Rosamond W, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB; on behalf of the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics—2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–e360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Songyang Z. Introduction to Telomeres and Telomerase. Vol 1587. New York, NY: Humana Press; 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mons U, Muezzinler A, Schottker B, Dieffenbach AK, Butterbach K, Schick M, Peasey A, De Vivo I, Trichopoulou A, Boffetta P, Brenner H. Leukocyte telomere length and all‐cause, cardiovascular disease, and cancer mortality: results from individual‐participant‐data meta‐analysis of 2 large prospective cohort studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maciejowski J, de Lange T. Telomeres in cancer: tumour suppression and genome instability. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18:175–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Helby J, Nordestgaard BG, Benfield T, Bojesen SE. Shorter leukocyte telomere length is associated with higher risk of infections: a prospective study of 75,309 individuals from the general population. Haematologica. 2017;102:1457–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Haycock PC, Heydon EE, Kaptoge S, Butterworth AS. Leucocyte telomere length and risk of cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMJ. 2014;349:g4227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhan Y, Karlsson IK, Karlsson R, Tillander A, Reynolds CA, Pedersen NL, Hagg S. Exploring the causal pathway from telomere length to coronary heart disease: a network Mendelian randomization study. Circ Res. 2017;121:214–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nzietchueng R, Elfarra M, Nloga J, Labat C, Carteaux JP, Maureira P, Lacolley P, Villemot JP, Benetos A. Telomere length in vascular tissues from patients with atherosclerotic disease. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15:153–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Spigoni V, Aldigeri R, Picconi A, Derlindati E, Franzini L, Haddoub S, Prampolini G, Vigna GB, Zavaroni I, Bonadonna RC, Cas A. Telomere length is independently associated with subclinical atherosclerosis in subjects with type 2 diabetes: a cross‐sectional study. Acta Diabetol. 2016;53:661–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nezu T, Hosimi N, Aoki S, Matsumoto M. Imaging of atherosclerosis: carotid intima‐media thickness. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2016;23:18–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Touboul PJ, Hennerici MG, Meairs S, Adams H, Amarenco P, Bornstein N, Csiba L, Desvarieux M, Ebrahim S, Hernandez Hernandez R, Jaff M, Kownator S, Naqvi T, Prati P, Rundek T, Sitzer M, Schminke U, Tardif JC, Taylor A, Vicaut E, Woo KS. Mannheim carotid intima‐media thickness and plaque consensus (2004–2006–2011): an update on behalf of the advisory board of the 3rd, 4th and 5th watching the risk symposia, at the 13th, 15th and 20th European Stroke Conferences, Mannheim, Germany, 2004, Brussels, Belgium, 2006, and Hamburg, Germany, 2011. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;34:290–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Veerasamy M, Ford GA, Neely D, Bagnall A, MacGowan G, Das R, Kunadian V. Association of aging, arterial stiffness, and cardiovascular disease: a review. Cardiol Rev. 2014;22:223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Juonala M, Jarvisalo MJ, Maki‐Torkko N, Kahonen M, Viikari JS, Raitakari OT. Risk factors identified in childhood and decreased carotid artery elasticity in adulthood: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Circulation. 2005;112:1486–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Laurent S, Cockcroft J, Van Bortel L, Boutouyrie P, Giannattasio C, Hayoz D, Pannier B, Vlachopoulos C, Wilkinson I, Struijker‐Boudier H. Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2588–2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. van den Oord SC, Sijbrands EJ, ten Kate GL, van Klaveren D, van Domburg RT, van der Steen AF, Schinkel AF. Carotid intima‐media thickness for cardiovascular risk assessment: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2013;228:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ben‐Shlomo Y, Spears M, Boustred C, May M, Anderson SG, Benjamin EJ, Boutouyrie P, Cameron J, Chen CH, Cruickshank JK, Hwang SJ, Lakatta EG, Laurent S, Maldonado J, Mitchell GF, Najjar SS, Newman AB, Ohishi M, Pannier B, Pereira T, Vasan RS, Shokawa T, Sutton‐Tyrell K, Verbeke F, Wang KL, Webb DJ, Willum Hansen T, Zoungas S, McEniery CM, Cockcroft JR, Wilkinson IB. Aortic pulse wave velocity improves cardiovascular event prediction: an individual participant meta‐analysis of prospective observational data from 17,635 subjects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:636–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fitzpatrick AL, Kronmal RA, Gardner JP. Leukocyte telomere length and cardiovascular disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Masi S, D'Aiuto F, Martin‐Ruiz C, Kahn T, Wong A, Ghosh AK, Whincup P, Kuh D, Hughes A, Zglinicki TC, Hardy R, Deanfield JE. Rate of telomere shortening and cardiovascular damage: a longitudinal study in the 1946 British Birth Cohort. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:3296–3303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. De Meyer T, Rietzschel ER, De Buyzere ML, Langlois MR, De Bacquer D, Segers P, Van Damme P, De Backer GG, Van Oostveldt P, Van Criekinge W, Gillebert TC, Bekaert S; Asklepios Study Investigators . Systemic telomere length and preclinical atherosclerosis: the Asklepios study. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:3074–3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fernández‐Alvira JM, Fuster V, Dorado B, Soberón N, Flores I, Gallardo M, Pocock S, Blasco MA, Andrés V. Short telomere load, telomere length, and subclinical atherosclerosis: the PESA study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:2467–2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang YY, Chen AF, Wang HZ, Xie LY, Sui KX, Zhang QY. Association of shorter mean telomere length with large artery stiffness in patients with coronary heart disease. Aging Male. 2011;14:27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McDonnell BJ, Yasmin Butcher L, Cockcroft JR, Wilkinson IB, Erusalimsky JD, McEniery CM. The age‐dependent association between aortic pulse wave velocity and telomere length. J Physiol. 2017;595:1627–1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thijssen DH, Carter SE, Green DJ. Arterial structure and function in vascular ageing: are you as old as your arteries? J Physiol. 2016;594:2275–2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wake M, Clifford S, York E, Davies S; Child Health CheckPoint Team . Introducing growing up in Australia's Child Health CheckPoint. Fam Matters. 2014;94:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Clifford S, Davies S, Wake M. Child Health CheckPoint: cohort summary and methodology of a physical health and biospecimen module for the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. BMJ Open. 2019;0:e020261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Edwards B. Growing up in Australia: the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children entering adolescence and becoming a young adult. Fam Matters. 2014;95:5–14. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sanson A, Johnstone R; The LSAC Research Consortium & FaCS LSAC Project Team . Growing up in Australia takes its first steps. Fam Matters. 2004;67:46–53. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kis E, Cseprekal O, Kerti A, Salvi P, Benetos A, Tisler A, Szabo A, Tulassay T, Reusz GS. Measurement of pulse wave velocity in children and young adults: a comparative study using three different devices. Hypertens Res. 2011;34:1197–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Selamet Tierney ES, Gauvreau K, Jaff MR, Gal D, Nourse SE, Trevey S, O'Neill S, Baker A, Newburger JW, Colan SD. Carotid artery intima‐media thickness measurements in the youth: reproducibility and technical considerations. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Papaioannou TG, Karatzis EN, Karatzi KN, Gialafos EJ, Protogerou AD, Stamatelopoulos KS, Papamichael CM, Lekakis JP, Stefanadis CI. Hour‐to‐hour and week‐to‐week variability and reproducibility of wave reflection indices derived by aortic pulse wave analysis: implications for studies with repeated measurements. J Hypertens. 2007;25:1678–1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Growing Up in Australia's Child Health CheckPoint: Standard Operating Procedure: Telomere Length Quantification. Melbourne, Australia: Murdoch Children's Research Institute; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nguyen MT, Lycett K, Vryer R, Burgner D, Ranganathan S, Grobler A, Wake M, Saffery R. Telomere length: population epidemiology and concordance in 11‐12 year old Australians and their parents. BMJ Open. 2019;0:e020263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu RS, Dunn S, Grobler A, Lange K, Becker D, Goldsmith G, Carlin J, Juonala M, Wake M, Burgner DP. Carotid artery intima‐media thickness, distensibility, and elasticity: population epidemiology and concordance in Australian 11‐12 year old Australians and their parents. BMJ Open. 2019;0:e020264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kahn F, Wake M, Lycett K, Clifford S, Burgner D, Goldsmith G, Grobler A, Lange K, Cheung M. Vascular function and stiffness: population epidemiology and concordance in Australian 11‐12 year‐olds and their parents. BMJ Open. 2019;0:e020896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Janner JH, Godtfredsen NS, Ladelund S, Vestbo J, Prescott E. Aortic augmentation index: reference values in a large unselected population by means of the SphygmoCor device. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:180–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Strazhesko I, Tkacheva O, Boytsov S, Akasheva D, Dudinskaya E, Vygodin V, Skvortsov D, Nilsson P. Association of insulin resistance, arterial stiffness and telomere length in adults free of cardiovascular diseases. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Butlin M, Qasem A, Battista F, Bozec E, McEniery CM, Millet‐Amaury E, Pucci G, Wilkinson IB, Schillaci G, Boutouyrie P, Avolio AP. Carotid‐femoral pulse wave velocity assessment using novel cuff‐based techniques: comparison with tonometric measurement. J Hypertens. 2013;31:2237–2243; discussion 2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hwang MH, Yoo JK, Kim HK, Hwang CL, Mackay K, Hemstreet O, Nichols WW, Christou DD. Validity and reliability of aortic pulse wave velocity and augmentation index determined by the new cuff‐based SphygmoCor Xcel. J Hum Hypertens. 2014;28:475–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wilkinson IB, McEniery CM, Schillaci G, Boutouyrie P, Segers P, Donald A, Chowienczyk PJ. ARTERY Society guidelines for validation of non‐invasive haemodynamic measurement devices: part 1, arterial pulse wave velocity. Artery Res. 2010;4:34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Butlin M, Qasem A. Large artery stiffness assessment using SphygmoCor technology. Pulse (Basel). 2017;4:180–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mundstock E, Sarria EE, Zatti H, Louzada F, Grun L, Jones M, Guma F, Memoriam J, Epifanio M, Stein RT, Barbé‐Tuana FM, Mattiello R. Effect of obesity on telomere length: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity. 2015;23:2165–2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mitchell C, Hobcraft J, McLanahan SS, Siegel SR, Berg A, Brooks‐Gunn J, Garfinkel I, Notterman D. Social disadvantage, genetic sensitivity, and children's telomere length. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:5944–5949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Astuti Y, Wardhana A, Watkins J, Wulaningsih W, Network PR. Cigarette smoking and telomere length: a systematic review of 84 studies and meta‐analysis. Environ Res. 2017;158:480–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer‐Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Guo SS, Wei R, Mei Z, Curtin LR, Roche AF, Johnson C. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data. 2000;314:1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ellul E, Wake M, Clifford S, Lange K, Würtz P, Juonala M, Dwyer T, Carlin J, Burgner D, Saffery R. Metabolomics: population epidemiology and concordance in 11‐12 year old Australians and their parents. BMJ Open. 2019;0:e020900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kalisch DW. National Health Survey: First Results. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Okuda K, Khan MY, Skurnick J, Kimura M, Aviv H, Aviv A. Telomere attrition of the human abdominal aorta: relationships with age and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2000;152:391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wilson WR, Herbert KE, Mistry Y, Stevens SE, Patel HR, Hastings RA, Thompson MM, Williams B. Blood leucocyte telomere DNA content predicts vascular telomere DNA content in humans with and without vascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2689–2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. O'Donnell CJ, Demissie S, Kimura M, Levy D, Gardner JP, White C, D'Agostino RB, Wolf PA, Polak J, Cupples LA, Aviv A. Leukocyte telomere length and carotid artery intimal medial thickness: the Framingham Heart Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1165–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Willeit P, Willeit J, Brandstätter A. Cellular aging reflected by leukocyte telomere length predicts advanced atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease risk. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1649–1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhang W, Zhu S, Zhao D, Jiang S, Li J, Li Z, Fu B, Zhang M, Li D, Bai X, Cai G, Sun X, Chen X. The correlation between peripheral leukocyte telomere length and indicators of cardiovascular aging. Heart Lung Circ. 2014;23:883–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Regina C, Panatta E, Candi E, Melino G, Amelio I, Balistreri CR, Annicchiarico‐Petruzzelli M, Di Daniele N, Ruvolo G. Vascular ageing and endothelial cell senescence: molecular mechanisms of physiology and diseases. Mech Ageing Dev. 2016;159:14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dudinskaya EN, Tkacheva ON, Shestakova MV, Brailova NV, Strazhesko ID, Akasheva DU, Isaykina OY, Sharashkina NV, Kashtanova DA, Boytsov SA. Short telomere length is associated with arterial aging in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocr Connect. 2015;4:136–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Benetos A, Okuda K, Lajemi M, Kimura M, Thomas F, Skurnick J, Labat C, Bean K, Aviv A. Telomere length as an indicator of biological aging. Hypertension. 2001;37:381–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Bohm M, Christiaens T, Cifkova R, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Galderisi M, Grobbee DE, Jaarsma T, Kirchhof P, Kjeldsen SE, Laurent S, Manolis AJ, Nilsson PM, Ruilope LM, Schmieder RE, Sirnes PA, Sleight P, Viigimaa M, Waeber B, Zannad F, Redon J, Dominiczak A, Narkiewicz K, Nilsson PM, Burnier M, Viigimaa M, Ambrosioni E, Caufield M, Coca A, Olsen MH, Schmieder RE, Tsioufis C, van de Borne P, Zamorano JL, Achenbach S, Baumgartner H, Bax JJ, Bueno H, Dean V, Deaton C, Erol C, Fagard R, Ferrari R, Hasdai D, Hoes AW, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, Lancellotti P, Linhart A, Nihoyannopoulos P, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Sirnes PA, Tamargo JL, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Wijns W, Windecker S, Clement DL, Coca A, Gillebert TC, Tendera M, Rosei EA, Ambrosioni E, Anker SD, Bauersachs J, Hitij JB, Caulfield M, De Buyzere M, De Geest S, Derumeaux GA, Erdine S, Farsang C, Funck‐Brentano C, Gerc V, Germano G, Gielen S, Haller H, Hoes AW, Jordan J, Kahan T, Komajda M, Lovic D, Mahrholdt H, Olsen MH, Ostergren J, Parati G, Perk J, Polonia J, Popescu BA, Reiner Z, Ryden L, Sirenko Y, Stanton A, Struijker‐Boudier H, Tsioufis C, van de Borne P, Vlachopoulos C, Volpe M, Wood DA. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2159–2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dalla Pozza R, Ehringer‐Schetitska D, Fritsch P, Jokinen E, Petropoulos A, Oberhoffer R; Association for European Paediatric Cardiology Working Group Cardiovascular Prevention . Intima media thickness measurement in children: a statement from the Association for European Paediatric Cardiology (AEPC) Working Group on Cardiovascular Prevention endorsed by the Association for European Paediatric Cardiology. Atherosclerosis. 2015;238:380–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. Supplemental methods.

Table S1. Equations for the Calculation of (I, II and III) Telomere Length and (IV) Carotid Elasticity

Table S2. Summary of Adults’ Vascular Outcomes for Diabetics, Current Smokers and Hypertension

Table S3. Summary of Adult T/S Ratios for Diabetics, Hypertension Medication Users

Table S4. Association of Brachial Systolic Blood Pressure (Exposure) With Telomere Length (Separately Outcome), in Children and Adults

Figure S1. Children's (green, solid) and adults’ (blue, dash) distribution of (I) carotid intima‐media thickness, (II) carotid‐femoral pulse wave velocity, (III) carotid elasticity and (IV) telomere length.