Adolescents and young adults (AYAs) between the ages of 15 and 39 years with cancer have been identified by the National Cancer Institute as a vulnerable population. While overall cancer survival rates have improved, there has been less improvement for AYAs with cancer. Factors contributing to widening outcome disparities in the AYA population include a higher uninsured rate than the general population, delayed diagnosis, loss of follow-up, lower participation in clinical trials, challenging psychosocial situations, and inconsistent treatment guidelines between adult and pediatric oncology.1

These contributing barriers interlink with one another similar to the ways in which the organs in our body interlink with one another. A higher uninsured rate results in more limited access to our health care system, which is the initiator of a domino effect leading to diagnostic delays, increased follow-up loss rate, and lower participation in clinical trials. Furthermore, limited access to our health care system creates physical, mental, and financial burdens for affected individuals.

Since its enactment in 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) has made substantial progress toward improving both access to insurance coverage and affordability of care for many low-income patients with cancer, including those inthe AYA demographics. Provisions in the ACA with particular importance to AYAs with cancer include guaranteed issue of insurance policies that no longer discriminate based on health status or pre-existing conditions, the elimination of lifetime caps on insurers’ coverage of in-network services, and the introduction of annual caps on patients’ out-of-pocket spending on in-network care. In addition, the ACA defined 10 essential health benefits that all insurance plans must cover. These protections, along with the ACA’s requirement that plans allow young adults to remain insured under a parent’s policy until their 26th birthday, have contributed to historical reductions in the uninsured rate among the AYA population. Our analysis of the 2010 to 2016 Current Population Survey showed that the uninsured rate among individuals aged 15 to 39 years declined from 26% to14%.2

While the ACA has made progress in improving access to coverage, distinct challenges for AYAs with cancer remain. One consequence of the ACA’s regulatory mandates is that they restrain insurers’ ability to lower premiums by adjusting patient cost-sharing (ie, deductibles, copayment, and coinsurance rates) and the scope of covered services. Therefore, while the ACA’s subsidies for low- and moderate-income families are designed to shield lower-income patients from high premiums, research has shown that insurers have increasingly turned to nonprice dimensions of plan contracts (eg, health care networks and drug formularies) as alternative cost-containment strategies.3,4

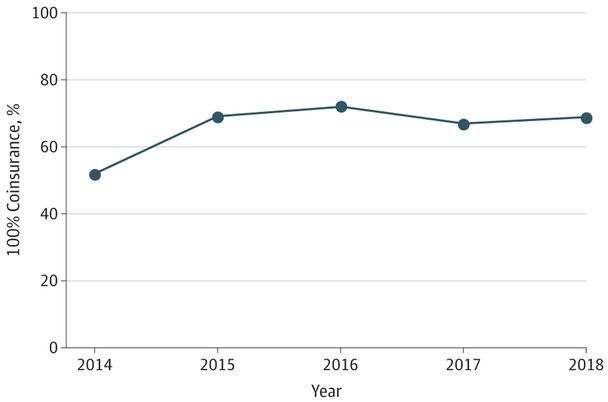

Plans with narrow health care networks have blossomed in the private health insurance marketplaces created by the ACA. These plans contract with a restricted set of often low-cost preferred health care professionals and many times offer little, if any, coverage of nonemergent out-of-network care. Research has found that narrow-network plans are more likely to exclude high-cost facilities, such as academic medical centers and comprehensive cancer centers,5 where clinical trials and oncology subspecialists familiar with both standard adult and pediatric treatment protocols are generally more readily accessible. In addition, access to in-network oncologists is often more restrictive in narrow-network plans,3 and since the ACA’s consumer and financial protections apply only to in-network care, such restriction has increased the risk of exposing AYAs with cancer to high-cost out-ofnetwork care with few, if any, financial guardrails. In fact, a majority of marketplace plans contain no out-of-network oncology coverage (Figure). Altogether, AYAs with cancer may be indirectly “discouraged” from receiving therapeutic managements that are more appropriate for them offered at academic medical centers or comprehensive cancer centers.6

Figure. Percentage of Markets With 100% Coinsurance for a Specialist Visit in the Least-Expensive Silver Plan.

Markets are defined at the rating area level, and the underlying sample is based on 393 rating areas in 34 states with federally facilitated marketplaces. Estimates are derived from 2014-2018 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services marketplace plan public use data file.

In addition to health care networks, insurers have turned to cost-savings strategies based on altering their prescription drug formularies. For antineoplastics, although coverage transparency has generally improved since2015, mostoral antineoplastics remain on the highest cost-sharing tiers, with some not even matching the cost-sharing information provided on the marketplace website.4 In essence, patients who need costly drugs (antineoplastics) face the greatest financial hazards, especially those with higher-deductible plans. Although this financial burden is somewhat ameliorated by various patient assistance programs, the long-term effects of such programs on patients’ access as well as health and financial outcomes remain to be examined, since such patient assistance subsidies may contribute to higher drug prices.7

Policy responses to narrow networks have thus far been spotty. Notably, oversight of an insurance plan’s network adequacy has largely fallen to private accreditation agencies and the states, where regulatory efforts to ensure network adequacy are more often reactive to specific patient criticism. Moreover, quantitative network adequacy standards, such as requirements that insurers contract with a sufficient number of primary care clinicians who are geographically proximate to the plan’s members, do not incorporate additional guidelines on access to oncologic care. For illustration, most plan accreditation agencies require plans to evaluate the availability of high-volume and high-effect specialists broadly, but failing to include oncology, in and of itself, will not necessarily prevent a plan from achieving accreditation.

As for oversight of prescription drug formularies, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has numeric standards for plans to meet. In practice, the pharmacy and therapeutics committees develop, manage, and update medications on a formulary, while cost decisions are left up to the insurers or pharmacy benefits managers.8 Nevertheless, 1 issue remains: many antineoplastics are administered nonorally, making them a medical rather than prescription drug benefit and, therefore, are provided with limited, if any, cost-sharing information on the marketplace website.

Although the ACA has made advancements, it has also created some consequences that are likely to have key implications for vulnerable populations, such as AYAs with cancer. Accordingly, health insurers, state regulators, and federal lawmakers should look toward offering ways to better facilitate consumers in making informed decisions for picking the right insurance plans, such as via value-based insurance designs with transparent health care network, tiered formularies, and benefits vs costs. For our AYAs with cancer, this may well be a key milestone step in helping to close the outcome disparity gap.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Graves’ contribution to this viewpoint is supported by grant R01 CA189152-01A1 from the National Cancer Institute. No other disclosures were reported.

Contributor Information

Peter Hsu, Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, Monroe Carell Jr Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee..

John A. Graves, Department of Health Policy, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee..

REFERENCES

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. Closing the Gap: Research and Care Imperatives for Adolescents and Young Adults With Cancer–Report of the Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group. https://www.cancer.gov/types/aya/research/ayao-august-2006.pdf. Published August 2006. Accessed September 1, 2017.

- 2.United States Census Bureau. Current population survey tables for health insurance coverage. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/cps-hi.html. Accessed March 30, 2018.

- 3.Sloan C, Carpenter E. Exchange plans include 34 percent fewer providers than the average for commercial plans. http://avalere.com/expertise/managed-care/insights/exchange-plans-include-34-percent-fewer-providers-than-the-average-for-comm. Published July15, 2015. Accessed October 4, 2017.

- 4.Cancer Action Network. ACS CAN Examination of Drug Coverage Network and Transparency in the Health Insurance Marketplace. https://www.acscan.org/sites/default/files/National%20Documents/QHP%20Formularies%20Analysis%20-%202017%20FINAL.pdf. Published February 22, 2017. Accessed September 15, 2017.

- 5.Yasaitis L, Bekelman JE, Polsky D. Relation between narrow networks and providers of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(27):3131–3135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolfson J, Sun C-L, Kang T, Wyatt L, D’Appuzzo M, Bhatia S. Impact of treatment site in adolescents and young adults with central nervous system tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(8):dju166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howard DH. Drug companies’ patient-assistance programs–helping patients or profits? N Engl J Med. 2014;371(2):97–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glover L. Your drug formulary: how it works and what to know. NerdWallet. https://www.nerdwallet.com/blog/health/drug-formularies-and-prescriptions/. Published June 13, 2016. Accessed September 15, 2017.