Abstract

Health Disparities (HD) are community-based, biomedical challenges in need of innovative contributions from Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) fields. Surprisingly, STEM professionals demonstrate a persistent lack of HD awareness and/or engagement in both research and educational activities. This project introduced Health Disparities (HD) as technical challenges to incoming undergraduates in order to elevate engineering awareness of HD. The objective was to advance STEM-based, HD literacy and outreach to young cohorts of engineers. Engineering students were introduced to HD challenges in technical and societal contexts as part of Engineering 101 courses. Findings demonstrate that student comprehension of HD challenges increased via joint study of rising health care costs, engineering ethics and growth of biomedical-related engineering areas.

Keywords: Health disparities, Ethics, Undergraduate education, Societal impact

Introduction

Health Disparities (HD) are preventable differences in the incidence, prevalence, mortality and burden of disease on communities targeted by factors such as gender, residence, ethnicity and/or socioeconomic status [1]. HD have become contemporary biomedical challenges with adverse and escalating effects in the United States (US) and worldwide. The cost of US health care has risen dramatically in the current decade, which has, both, aggravated federal spending forecasts and highlighted a charged political climate surrounding health inequality [2]. The portion of increased costs attributed to HD has yet to be quantitatively and objectively evaluated, but is certain to rise commensurate with currently-reported levels of HD across different communities [3,4].

The interdisciplinary nature of engineering can help decipher many current and developing HD challenges by leveraging engineering underpinnings to integrate technology with fundamental science, clinical therapies and health outcomes. Further, joint biomedical- related engineering ventures have impacted US public policy [5], health initiatives [6] and community-based challenges [7], all of which can uniquely address HD challenges. In order to fully evaluate HD as technical engineering challenges, however, the community must address the persistent lack of HD engagement among professionals in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) disciplines. Researchers and educators must also ameliorate the lack of HD awareness among the youngest engineers-in-training, e.g. PK-12 and undergraduates [8,9].

This brief describes a 4-year project undertaken to advance STEM- based HD literacy [10] and outreach to current and future STEM professionals. The objective was to elevate engineering awareness of HD challenges by incorporating health care data alongside ongoing HD research into introductory courses that describe potential career paths and research directions for engineers.

Materials and Methods

This project was conducted with incoming undergraduate cohorts (first year students and transfers) at the Grove School of Engineering at the City College of New York (CCNY) over 4 years. Students in the introductory engineering course (ENGR 101) were given surveys and assignments to complete, whose results were statistically analyzed using the student’s t-test and post-hoc Tukey test. The overall course goal was to expose new students to potential engineering careers using small projects and assignments that cultivate their requisite technical skills. Each cohort in this study was comprised of 135–155 students, per year, all of whom were declared engineering majors and were predominantly under the age of 25.

CCNY heralds the only accredited, public engineering school in New York City, and is the flagship campus of the 24 schools that comprise the City University of New York (CUNY). CCNY is also a Minority Serving Institution [11] in which more than 51% of enrolled students identify as African-American, Hispanic-American, Native- American or Pacific Islander (as per guidelines of the US National Science Foundation, NSF).

Results

This project introduced the concepts of health disparities (HD) to incoming students via the required, introductory course in Engineering. This was executed in two parts: (a) Placing HD and STEM fields in the context of US health care costs and (b) Using HD data as part of technical engineering training. Assessment of increased student HD awareness upon course completion was also measured.

Rising health care costs and opportunities for engineers

Incoming engineering students were introduced to the rising costs of US health care alongside the increasing numbers of STEM majors. As shown in Figure 1A, the federal expense of health care per capita currently approaches $10,500 or 18% of the country’s Gross Domestic Product [12] (GDP, per the US Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services www.cms.gov). More poignantly, this costly trend has increased dramatically in the current decade and is expected to continue. In complement, data in Figure 1B illustrates the growing numbers of STEM baccalaureate degrees awarded from US accredited programs [13], as per NSF analyses (www.nsf.gov). This academic trend has steadily increased through 2017, where nearly one third of all US baccalaureate degrees were awarded in STEM [14].

Figure 1:

Current trends in US health care costs and STEM education. (A) The rising cost of US health care per capita over time (Source CMS.gov); (B) Increasing numbers of US accredited baccalaureate degrees in STEM fields awarded per year (source NSF.gov).

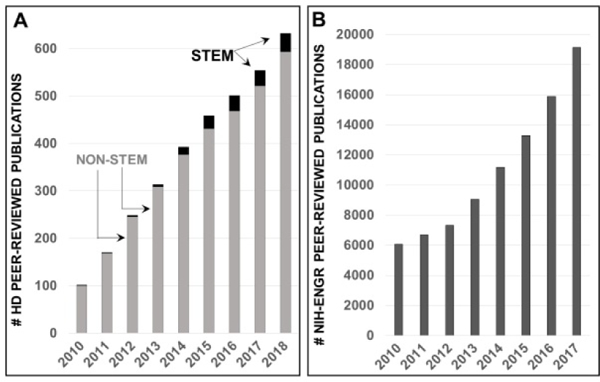

Using this national data, courses discussed unique interdisciplinary opportunities for engineers in health care and policy, as well as introduced the concepts of HD and community-based challenges in global and US health. Figure 2A illustrates the rising numbers of peer-reviewed HD research articles with funding from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) alongside the small but growing fraction of STEM-based HD contributions since 2010. By contrast, Figure 2B depicts the exponential rise in engineering, peer-reviewed publications with NIH funding in the present decade. These data side-by-side illustrate the need and opportunities for engineers to address HD challenges within their developing careers.

Figure 2:

Growth of US federally-funded Health Disparities research alongside engineering research. (A) Growth of peer-reviewed research publications in Health Disparities funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the current decade; both STEM and non-STEM-based studies depicted; (B) Rising numbers of NIH-funded peer-reviewed publications from engineering groups (ENGR).

Integration of health disparities into engineering preparation

The second part of the project utilized HD data for technical assignments that developed statistical problem-solving skills needed in engineering professions. Students manipulated and analyzed epidemiological data from select US case studies of well-known HD challenges, e.g. cardiovascular disease [15], obesity [16] and vision loss [17]. In complement, engineers examined peer-reviewed literature of well-studied origins and agents of HD (per case study) as part of engineering ethics. Here, students were introduced to the research code of conduct [18] and its overlap with themes in social science [19], community health and public policy [20]. As per Table 1, the material highlighted how each HD agent related to STEM research and clinical trials [21–26], genetic screening [27–29], engineering technology [30,31], health care policy/access [32,33], quality of care [34–38] and historical societal factors [39–44].

Table 1:

Summary of peer-reviewed literature describing well-known agents of Health Disparities discussed in engineering alongside US case studies.

| HD Agents | Description of Concerns | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Trials | Homogeneous patient groups | [21,22,25,41] |

| Gender imbalance | [23,24,26] | |

| Genetic Screening | Lacking determinants of disease progression | [28,29] |

| Non-inclusive of resistance to treatments/therapies | [37] | |

| Technologies and Tools | Tested using homogenous patient groups | [27,30,31] |

| Access and Quality | Insurance cost and billing | [32,33,36] |

| Physician and clinical networks | [34,35] | |

| Historical and Societal Factors | Distrust of medical community | [38,39,42] |

| Non-diverse workforce | [40,43,44] |

Assessment of increased health disparities awareness

The project, lastly, measured student awareness of HD challenges and how BME could be expanded with an HD context. Students were asked to provide an answer to the question, ‘Why are challenges in US Health Disparities important?’ at both the beginning and end of the course. As shown in Figure 3A, on the first day, 45% of students answered ‘I don’t know’, while 33% listed different types of health insurance plans. Another 12% claimed HD challenges were not important and the remaining students stated that HD was only relevant with certain diseases (notably diabetes was specifically mentioned in nearly all cases [45]).

Figure 3:

Student responses to ‘Why are challenges in US Health Disparities important? (A) Mean answers at the beginning of the course and (B) at course completion. Data reported is the mean value +/− one deviation of 4 years of incoming engineering cohorts.

By contrast, Figure 3B illustrates the definitions provided to the fill- in question at course completion. As seen, the majority of students stated HD challenges were important because they were caused by, or were symptoms of, inequity and unfairness in health services, health research, and/or health care (31%). Other large student cohorts replied that HD challenges were important because ‘They disproportionately affect my community’ (28%) and were ‘A great national expense’ (29%).Another 12% of undergraduates stated that HD challenges were important because they were in need of engineering tools.

Discussion

The growth of Health Disparities (HD) across different communities of Americans represents a biomedical challenge that has engaged few engineering professionals. Technical curricula lag in introducing HD challenges as opportunities for engineering innovation and impact, despite record numbers of STEM degrees awarded this decade. This brief describes a strategy with which to introduce engineering majors to HD challenges in a technical context. Introductory 101 courses became ideal nucleation sites because HD comprehension requires a technical grasp of statistical analyses fundamental to all engineering experiments. In addition, HD challenges simultaneously introduce contemporary themes within engineering ethics that interface with public policy, generational societal activism [46] and ABET accreditation requirements [47]. As such, data sets that highlighted the incidence or progression of disease within communities targeted by residence, age and/or education level (for example) elucidated HD in joint technical and societal contexts. Such a juxtaposition is often cited for selection of the engineering major (particular biomedical engineering [47]), underscoring HD challenges as natural, but underdeveloped, areas for engineering innovation.

The responses from engineering cohorts recorded in this project illustrate two main themes. First, incoming engineers were often unaware of the high cost of health care or the prevalence of HD in the US. This is expected, as students can rely upon their parents for US medical insurance until the age of 25, as a whole are among the healthiest cohorts of Americans, and are minimally exposed to disparities in disease progression and/or burden within their age group [48]. Second, collective awareness of HD resonated most strongly through personal connections with communities adversely affected by HD challenges, as well as through the demonstrated imbalance in inflated cost and high inequality in American health. These themes are meaningful for engineering engagement in HD, as students who question HD underpinnings are motivated to use their engineering skills to help achieve medical parity. Further, associating HD with one’s own communities will produce a larger diversity of professionals who undertake HD challenges, uplifting US workforce diversity in STEM and overall [40,43,49]. In these ways, early exposure to HD challenges may help engineers continue in HD-related careers via advanced study in graduate, medical or law schools, as well as increasingly quantitative programs in community health, physician assistant [50] or advanced nursing specialties [51].

Future projects will develop comprehensive strategies to increase engineering engagement in HD by: (a) Integrating HD data into research and engineering design projects; (b) Incorporating underlying HD medical principles into required STEM courses; and (c) Using HD challenges to improve experimental design procedures. Ambitious programmatic actions include developing an HD-based engineering ethics curriculum and creating an HD certificate program or approved engineering minor in Health Disparities jointly with community and public health programs.

Conclusions

Introducing engineering undergraduates to HD literature in joint technical and societal contexts increases student awareness and comprehension of these complex community-based challenges. Early exposure to HD as engineering challenges will help increase the number of HD-related researchers in STEM and incorporate HD into engineering ethics and technical curricula.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the Electrical Engineering Department at the Grove School of Engineering for supporting this study in its yearly administration of Engineering 101.

Financial Support

Funding for this project was provided by the National Institutes of Health (NCI U54CA132378, NEI R21EY026752) and the National Science Foundation (CBET 0939511).

References

- 1.Bleich SN, Jarlenski MP, Bell CN, LaVeist TA (2012) Health inequalities: Trends, progress, and policy. Annu Rev Public Health 33: 7–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krieger N (2012) Who and what is a “population”? Historical debates, current controversies, and implications for understanding “population health” and rectifying health inequities. Milbank 90: 634–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matthews KA, Croft JB, Liu Y, Lu H, Kanny D, et al. (2017) Health-related behaviors by urban-rural county classification-United States, 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ 66: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallack L, Thornburg K (2016) Developmental origins, epigenetics, and equity: Moving upstream. Matern Child Health J 20: 935–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider B, Schneider FK, de Andrade Lima da Rocha CE, Dallabona CA(2010) The role of biomedical engineering in health system improvement and nation’s development. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2010: 6248–6251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berge JM, Adamek M, Caspi C, Loth KA, Shanafelt A, et al. (2017) Healthy eating and activity across the lifespan (HEAL): A call to action to integrate research, clinical practice, policy, and community resources to address weight-related health disparities. Prev Med 101: 199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minkler M (2005) Community-based research partnerships: Challenges and opportunities. J Urban Health 82: ii3-ii12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benabentos R, Ray P, Kumar D (2014) Addressing health disparities in the undergraduate curriculum: An approach to develop a knowledgeable biomedical workforce. CBE Life Sci Educ 13: 636–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vazquez M, Marte O, Barba J, Hubbard K (2017) An approach to integrating health disparities within undergraduate biomedical engineering education. Ann Biomed Eng 45: 2703–2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernandez L, French M, Parker R (2017) Roundtable on health literacy: Issues and impact. Stud Health Technol Inform 240: 169–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper KJ (2012) CCNY minority scholars program nurtures Ph.D. aspirations. Diverse: Issues in Higher Education. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carrasquillo O, Mueller M (2018) Refinement of the affordable care act: A progressive perspective. Annu Rev Med 69: 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Science Foundation (2014) Science and engineering indicators 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCarthy N (2017) The countries with the most stem graduates. Forbes (Statistica). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mouton CP, Hayden M, Southerland JH (2017) Cardiovascular health disparities in underserved populations. Prim Care 44: e37–e71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mendy VL, Vargas R, Cannon-Smith G, Payton M (2017) Overweight, obesity, and extreme obesity among Mississippi adults, 2001–2010 and 2011–2015. Prev Chronic Dis 14: E49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eisner A (2015) Sex, eyes, and vision: Male/female distinctions in ophthalmic disorders. Curr Eye Res 40: 96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santos J, Palumbo F, Molsen-David E, Willke RJ, Binder L, et al. (2017) 37. ISPOR code of ethics 2017 (4th edn). Value Health 20: 1227–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez JM (2018) Health disparities, politics, and the maintenance of the status quo: A new theory of inequality. Soc Sci Med 200: 36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh GK, Daus GP, Allender M, Ramey CT, Martin EK, et al. (2017) Social determinants of health in the United States: Addressing major health inequality trends for the nation, 1935–2016. Int J MCH AIDS 6: 39 139–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen MS, Lara PN, Dang JH, Paterniti DA, Kelly K (2014) Twenty years post-NIH revitalization Act: Enhancing minority participation in clinical 40. trials (EMPaCT): Laying the groundwork for improving minority clinicaltrial accrual: Renewing the case for enhancing minority participation in cancer clinical trials. Cancer 120: 1091–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corbie-Smith G, St George DM, Moody-Ayers S, Ransohoff DF (2003) Adequacy of reporting race/ethnicity in clinical trials in areas of health disparities. J Clin Epidemiol 56: 416–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raparelli V, Pannitteri G, Todisco T, Toriello F, Napoleone L, et al. (2017) Treatment and response to statins: Gender-related differences. Curr Med Chem 24: 2628–2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graham G, Xiao YK, Taylor T, Boehm A (2017) Analyzing cardiovascular treatment guidelines application to women and minority populations. 44. SAGE Open Med 5: 2050312117721520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grover S, Xu M, Jhingran A, Mahantshetty U, Chuang L, et al. (2017) Clinical trials in low and middle-income countries-Successes and challenges. Gynecol Oncol Rep 19: 5–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKenney KM, Martinez NG, Yee LM (2017) Patient navigation across the spectrum of women’s health care in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol pii: 30944–30944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rana HQ, Cochrane SR, Hiller E, Akindele RN, Nibecker CM, et al. (2017) A comparison of cancer risk assessment and testing outcomes in patients from underserved vs. tertiary care settings. J Community Genet. 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmad A, Azim S, Zubair H, Khan MA, Singh S, et al. (2017) Epigenetic basis of cancer health disparities: Looking beyond genetic differences. 48. Biochim Biophys Acta 1868: 16–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schroff P, Gamboa CM, Durant RW, Oikeh A, Richman JS, et al. (2017) Vulnerabilities to health disparities and statin use in the regards (reasons 49. for geographic and racial differences in stroke) study. J Am Heart Assoc pii: e005449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glover MT, Daye D, Khalilzadeh O, Pianykh O, Rosenthal DI, et al. (2017) Socioeconomic and demographic predictors of missed opportunities to provide advanced imaging services. J Am Coll Radiol 14: 1403–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ostbring MJ, Eriksson T, Petersson G, Hellstrom L (2018) Motivational interviewing and medication review in coronary heart disease (mimeric): Intervention development and protocol for the process evaluation. JMIR Res Protoc 7: e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zewde N, Berdahl T (2001) Children’s usual source of care: Insurance, income, and racial/ethnic disparities, 2004–2014. Statistical Brief. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samson LW, Finegold K, Ahmed A, Jensen M, Filice CE, et al. (2017) Examining measures of income and poverty in medicare administrative data. Med Care 55: e158–e163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ricketts TC (2000) The changing nature of rural health care. Annu Rev Public Health 21: 639–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ofili E, Igho-Pemu P, Lapu-Bula R, Quarshie A, Obialo C, et al. (2005) The community physicians’ network (CPN): An academic-community partnership to eliminate healthcare disparities. Ethn Dis 15: S5–124-127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu T, Park A, Bai G, Joo S, Hutfless SM, et al. (2017) Variation in emergency department vs internal medicine excess charges in the United States. JAMA Intern Med 177: 1139–1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brunson JC, Laubenbacher RC (2018) Applications of network analysis to routinely collected health care data: A systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 25: 210–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Betancourt JR, Maina AW (2004) The institute of medicine report “Unequal Treatment”: Implications for academic health centers. Mt Sinai J Med 71: 314–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thurman WA, Harrison T (2017) Social context and value-based care: A capabilities approach for addressing health disparities. Policy Polit Nurs Pract 18: 26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Horvat L, Horey D, Romios P, Kis-Rigo J (2014) Cultural competence education for health professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 5: CD009405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kurt A, Kincaid H, Semler L, Jacoby JI, Johnson MB, et al. (2017) Impact of race versus education and race versus income on patients’ motivation to participate in clinical trials. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCartney G, Hearty W, Taulbut M, Mitchell R, Dryden R, et al. (2017) Regeneration and health: A structured, rapid literature review. Public Health 148: 69–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White AA 3rd (1999) Ustifications and needs for diversity in orthopaedics. Clin Orthop Relat Res 22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Creamer J, Attridge M, Ramsden M, Cannings-John R, Hawthorne K (2016) Culturally appropriate health education for type 2 diabetes in ethnic minority groups: An updated Cochrane review of randomized controlled trials. Diabet Med 33l: 169–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schabert J, Browne JL, Mosely K, Speight J (2013) Social stigma in diabetes: A framework to understand a growing problem for an increasing epidemic. Patient 6: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karwat DM, Eagle WE, Wooldridge MS, Princen TE (2015) Activist engineering: Changing engineering practice by deploying praxis. Sci Eng Ethics 21: 227–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barabino G (2013) A bright future for biomedical engineering. Ann Biomed Eng 41: 221–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soni A, Mitchell E (2001) Expenditures for commonly treated conditions among adults age 18 and older in the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population, 2013. Statistical Brief. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mensah MO, Sommers BD (2016) The policy argument for healthcare workforce diversity. J Gen Intern Med 31: 1369–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.White DM, Stephens P (2018) State of evidence-based practice in physician assistant education. J Physician Assist Educ 29: 12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hickman LD, DiGiacomo M, Phillips J, Rao A, Newton PJ, et al. (2018) Improving evidence based practice in postgraduate nursing programs: A systematic review: Bridging the evidence practice gap (BRIDGE project). Nurse Educ Today 63: 69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]