C. scindens is one of a few identified gut bacterial species capable of converting host cholic acid into disease-associated secondary bile acids such as deoxycholic acid. The current work represents an important advance in understanding the nutritional requirements and response to bile acids of the medically important human gut bacterium, C. scindens ATCC 35704. A defined medium has been developed which will further the understanding of bile acid metabolism in the context of growth substrates, cofactors, and other metabolites in the vertebrate gut. Analysis of the complete genome supports the nutritional requirements reported here. Genome-wide transcriptomic analysis of gene expression in the presence of cholic acid and deoxycholic acid provides a unique insight into the complex response of C. scindens ATCC 35704 to primary and secondary bile acids. Also revealed are genes with the potential to function in bile acid transport and metabolism.

KEYWORDS: Clostridium scindens, RNA-Seq, bile acid, defined medium, deoxycholic acid, growth factor requirements

ABSTRACT

In the human gut, Clostridium scindens ATCC 35704 is a predominant bacterium and one of the major bile acid 7α-dehydroxylating anaerobes. While this organism is well-studied relative to bile acid metabolism, little is known about the basic nutrition and physiology of C. scindens ATCC 35704. To determine the amino acid and vitamin requirements of C. scindens, the leave-one-out (one amino acid group or vitamin) technique was used to eliminate the nonessential amino acids and vitamins. With this approach, the amino acid tryptophan and three vitamins (riboflavin, pantothenate, and pyridoxal) were found to be required for the growth of C. scindens. In the newly developed defined medium, C. scindens fermented glucose mainly to ethanol, acetate, formate, and H2. The genome of C. scindens ATCC 35704 was completed through PacBio sequencing. Pathway analysis of the genome sequence coupled with transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq) under defined culture conditions revealed consistency with the growth requirements and end products of glucose metabolism. Induction with bile acids revealed complex and differential responses to cholic acid and deoxycholic acid, including the expression of potentially novel bile acid-inducible genes involved in cholic acid metabolism. Responses to toxic deoxycholic acid included expression of genes predicted to be involved in DNA repair, oxidative stress, cell wall maintenance/metabolism, chaperone synthesis, and downregulation of one-third of the genome. These analyses provide valuable insight into the overall biology of C. scindens which may be important in treatment of disease associated with increased colonic secondary bile acids.

IMPORTANCE C. scindens is one of a few identified gut bacterial species capable of converting host cholic acid into disease-associated secondary bile acids such as deoxycholic acid. The current work represents an important advance in understanding the nutritional requirements and response to bile acids of the medically important human gut bacterium, C. scindens ATCC 35704. A defined medium has been developed which will further the understanding of bile acid metabolism in the context of growth substrates, cofactors, and other metabolites in the vertebrate gut. Analysis of the complete genome supports the nutritional requirements reported here. Genome-wide transcriptomic analysis of gene expression in the presence of cholic acid and deoxycholic acid provides a unique insight into the complex response of C. scindens ATCC 35704 to primary and secondary bile acids. Also revealed are genes with the potential to function in bile acid transport and metabolism.

INTRODUCTION

Humans synthesize primary bile acids, cholic acid (CA; 3α,7α,12α-trihydroxy-5β-cholan-24-oic acid) and chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA; 3α,7α-dihydroxy-5β-cholan-24-oic acid), from cholesterol in the liver (1, 2). These two primary bile acids, conjugated to taurine or glycine, are secreted into the small intestine and play vital roles in digestion of dietary lipids (1, 2). However, several hundred milligrams of unconjugated CA and CDCA are converted to the toxic secondary bile acids deoxycholic acid (DCA; 3α,12α-dihydroxy-5β-cholan-24-oic acid) and lithocholic acid (LCA; 3α-monohydroxy-5β-cholan-24-oic acid), respectively, in the human colon each day (3). Removal of the 7α-hydroxyl group requires a multienzyme pathway known as the bile acid 7α-dehydroxylation pathway (4).

The bile acid 7α-dehydroxylation pathway is the result of a bile acid-inducible (bai) regulon in a small number of identified Firmicutes in the genus Clostridium, including Clostridium scindens and Clostridium hylemonae in cluster XIVa, Clostridium hiranonis, Clostridium sordellii, and Clostridium bifermentans in cluster XI, and Clostridium leptum in cluster IV (5). C. scindens is considered a high-activity bile acid 7α-dehydroxylating bacterium, with reported activity ∼100-fold higher than that of cluster XI and IV members (6). The first C. scindens isolate was reported by White et al. (1980) and named Eubacterium sp. strain VPI 12708 (7). It was in this study that the first indication that the genes encoding enzymes that convert CA to DCA and CDCA to LCA, respectively, were induced by CA but not DCA (7). Decades later, Eubacterium VPI 12708 was reclassified to C. scindens VPI 12708 (8). Shortly after the initial first report of Eubacterium VPI 12708, Clostridium strain 19, a human fecal strain capable of the side chain cleavage of cortisol to 11β-hydroxyandrostendione, was isolated (9). Clostridium strain 19 was renamed Clostridium scindens; the specific epithet “scindens” means “to cut,” owing to the steroid-17,20-desmolase activity observed following incubation with cortisol (10). This C. scindens isolate became the type strain (ATCC 35704) and was also shown to convert CA to DCA (10). C. scindens ATCC 35704 is a chemoheterotrophic, endospore-forming obligate anaerobe (11). Cells are nonmotile, occurring singly or in chains, and spores are terminal (11). Previous studies have identified carbohydrates such as d-glucose, d-lactose, d-fructose, d-mannose, d-ribose, and d-xylose as carbon and energy sources for C. scindens (11). C. scindens does not produce enzymes such as lecithinase, lipase, or catalase and is unable to digest gelatin, milk, and meat (11). This bacterium is also incapable of reducing nitrate or hydrolyzing starch and esculin; however, hydrogen sulfide is produced in sulfide-indole motility medium (11).

Molecular cloning and enzymology of bile acid-inducible (bai) genes (3) revealed a complex, multistep biochemical pathway distinct from the two-step mechanism originally proposed by Bergstrom et al. (12). Recently, crystal structures and catalytic mechanisms for the NAD(H)-dependent 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (BaiA) and the rate-limiting bile acid 7α-dehydratase (BaiE) have been reported (13, 14). Surprisingly, very little is known about nutritional requirements and end products of glucose metabolism by C. scindens ATCC 35704. Bile acid 7α-dehydroxylation is a redox process, resulting in a net 2-electron reduction involving flavin and pyridine nucleotides (3, 4). Global transcriptional responses to CA and DCA are predicted to enhance our understanding of the bai regulon, overall physiological changes to bile acid substrates and products, and microbial adaptation to the toxic and detergent nature of bile acids.

Global transcriptional analyses of bile acid 7α-dehydroxylating bacteria after bile acid induction have yet to be reported. C. scindens ATCC 35704 has traditionally been cultivated in complex, undefined medium (UM) for bile acid studies (6–11, 15, 16). Problematically for bile acid transformation and transcriptional studies, complex media do not allow exchange or limitation of nutrients, and, being composed partially of animal by-products (e.g., peptone and brain heart infusion [BHI]), contain bile acids and other lipids (17). The purpose of this study was to define the nutritional requirements of C. scindens ATCC 35704, to identify major end products of glucose fermentation during growth in a defined medium, and to determine transcriptional responses to bile acids under defined culture conditions. Here, we report development of a defined medium (DM) that supports the growth of C. scindens ATCC 35704. The genome of C. scindens ATCC 35704 has been closed through PacBio sequencing. The genomic data provide insight into the nutritional requirements of C. scindens and allowed comprehensive scaffolding of transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq) data during growth in DM. Our results describe the transcriptional response of C. scindens ATCC 35704 to the newly formulated DM, as well as to primary and secondary bile acids.

RESULTS

Development of defined and minimal media for C. scindens ATCC 35704.

To determine amino acid and vitamin requirements of C. scindens, a leave-one-out technique was utilized to eliminate nonessential amino acids and vitamins (data not shown). Tryptophan was the only amino acid that when omitted precluded growth of C. scindens ATCC 35704. When tryptophan was the sole amino acid provided in DM, growth was supported, signifying that tryptophan was the only amino acid required for growth by C. scindens ATCC 35704 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). C. scindens ATCC 35704 thus displays auxotrophy for tryptophan. When vitamins were omitted one at a time, C. scindens ATCC 35704 was found to clearly require riboflavin and pantothenic acid, and the reduced growth observed after three sequential transfers in the absence of pyridoxal HCl suggested that this vitamin might also be a growth factor for C. scindens ATCC 35704 (Fig. S2A). Indeed, only when the combination of riboflavin, pantothenic acid, and pyridoxal HCl were present together was growth maintainable (Fig. S2B). Based on these findings, a minimal medium (MM) was developed; MM was DM modified to contain riboflavin, pantothenic acid, and pyridoxal HCl as sole vitamins and tryptophan as the sole amino acid.

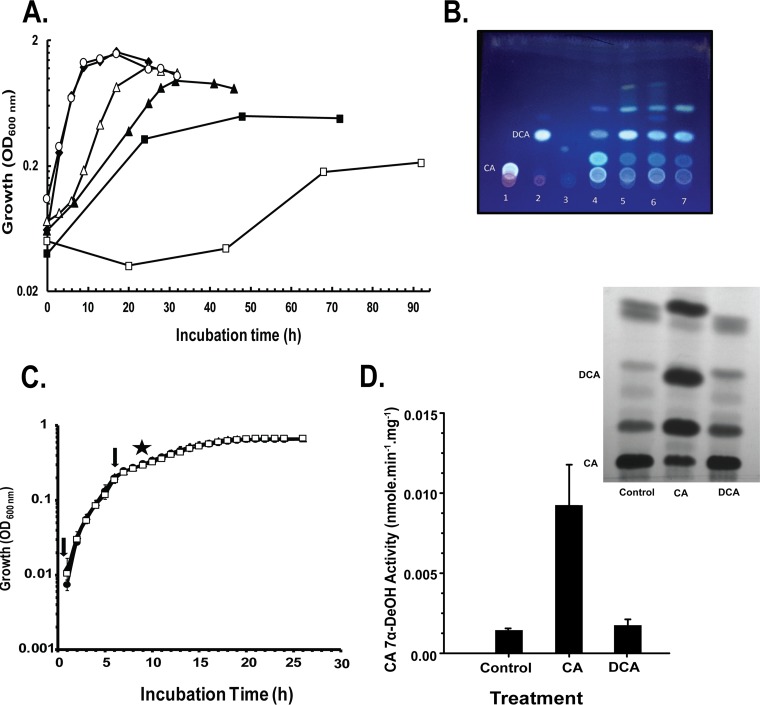

In MM and PO4-buffered MM cultures, glucose-dependent growth by C. scindens ATCC 35704 was slow, and cell yields were reduced compared to levels with DM and PO4-buffered DM cultures (Fig. 1A). These findings suggest that the sparse nutrients found in minimal medium were a metabolic (e.g., anabolic) challenge to C. scindens ATCC 35704. Doubling times for cells grown in BHI, UM, DM, and PO4-buffered DM approximated 2.0, 2.3, 3.3, and 7.0 h, respectively. While previous work has shown that CA is 7α-dehydroxylated to DCA by cells grown in BHI medium (15), we report here CA conversion to DCA by C. scindens ATCC 35704 grown in a defined or minimal medium (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, growth in PO4-buffered DM was not altered by addition of a final concentration of 100 μM CA or DCA (Fig. 1C). The bile acid concentration chosen reflects both in vivo physiologically relevant concentrations of bile acids in fecal water (18, 19) and concentrations used previously in numerous in vitro studies of C. scindens strains (6, 10, 15). Separate additions of CA in early and mid-log phase have been previously shown to result in robust induction of the bai regulon (7).

FIG 1.

Growth and bile acid metabolism by Clostridium scindens ATCC 35704. (A) Growth profiles after a minimum of three sequential transfers under each culture condition: ♦, brain heart infusion (BHI) broth; ○, undefined medium (UM; DM with 0.1% yeast extract); Δ, defined medium (DM); ▲, PO4-buffered DM; ■, minimal medium (MM); and □, PO4-buffered MM. (B) Bile acid metabolism in DM and MM (left to right): lane 1, cholate (CA) standard; lane 2, deoxycholate (DCA) standard; lane 3, DM and C. scindens 35704; lane 4, DM with CA, and C. scindens 35704; lane 5, DM modified to contain tryptophan as the sole amino acid plus CA and C. scindens 35704; lane 6, DM modified to contain riboflavin, pantothenic acid, and pyridoxal HCl as sole vitamins plus CA and C. scindens 35704; and lane 7, MM with CA and C. scindens 35704. The initial concentration of CA and DCA in standards and CA in cultures was 100 µM. (C) Growth profiles in PO4-buffered DM in the absence (control, ▲) and presence of cholic acid (CA, □) or deoxycholic acid (DCA, ●). Arrows indicate addition of 50 μM bile acid, and the star indicates addition of RNAprotect for RNA-Seq analysis as well as removal of a 1-ml aliquot for the [24-14C]CA conversion assay. (D) Determination of the rate of conversion of [24-14C]CA to [24-14C]DCA. The inset is the autoradiograph of TLC-separated [24-14C]CA metabolites. CA and 7-oxo-DCA were scraped and counted, and DCA and 3-oxo-DCA were scraped and counted.

To obtain cells for RNA isolation, C. scindens ATCC 35704 was acclimated to PO4-buffered DM (control) or to PO4-buffered DM with 100 μM CA or DCA by two consecutive 24-h transfers. On the third transfer, 50 μM CA, 50 μM DCA, or methanol vehicle control (<5%, vol/vol) was introduced at the time of inoculation and again at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.25 for a final concentration of 100 μM. At an OD600 of 0.45, the rate of conversion of [24-14C]CA to [24-14C]DCA over a 20-min interval was determined from 1 ml of culture to be 0.013 ± 6.5E−4 nmol min−1 mg−1 for control whole cells, 0.09 ± 0.025 nmol min−1 mg−1 for CA-induced whole cells, and 0.017 ± 4.1E−3 nmol min−1 mg−1 for DCA-induced whole cells (Fig. 1D). After it was confirmed that CA and DCA at 100 μM did not significantly alter growth patterns for C. scindens ATCC 35704 and that CA was converted to DCA in CA-induced, but not DCA or vehicle control whole cells, RNA was isolated from RNAprotect-treated cells for genome-wide transcriptomics.

Complete genome of Clostridium scindens ATCC 35704 and RNA-Seq analyses.

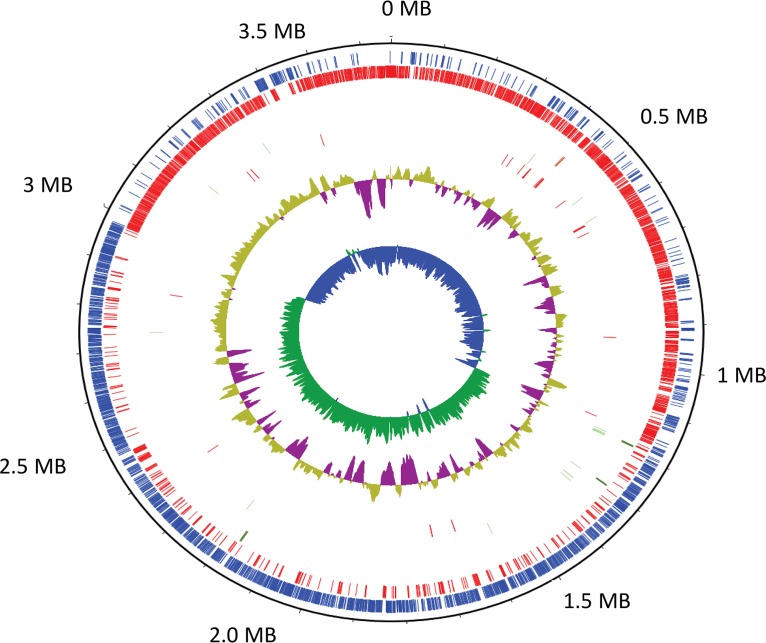

We next wanted to complete the genome of C. scindens ATCC 35704 in order to assess the genomic basis for the determined nutritional requirements, as well as to obtain a complete scaffold for mapping mRNA sequencing reads. The closed genome of C. scindens ATCC 35704 was obtained by PacBio sequencing using SMRT (single-molecule real-time) technology. The genome consists of a single circular chromosome of 3,658,040 bp, containing 3,657 coding sequences (CDS), 12 rRNA genes, 4 rRNA cistrons, each containing the three expected genes (5S, 16S, and 23S), and 58 tRNA genes (Fig. 2). Annotation of the genome reveals that most of the biosynthetic pathways considered essential for growth and viability appear to be present (e.g., biosynthesis of vitamins, amino acids, purines, and pyrimidines). Importantly, and consistent with results from our nutritional requirement studies, genes involved in the biosynthesis of tryptophan, riboflavin, pyridoxal phosphate, and pantothenic acid appear to be absent. Tryptophan was the only amino acid determined necessary for growth of C. scindens ATCC 35704 (Fig. S1). C. scindens ATCC 35704 has the genes for the complete shikimate pathway leading to chorismate and then to prephenate, whose bifurcation results in the formation of phenylalanine and tyrosine. Routes into the shikimate pathway include the pentose-phosphate pathway (erythrose-4-phosphate) and quinic acid. However, C. scindens ATCC 35704 lacks genes involved in anthranilate synthesis and metabolism (trpEGDFC). Tryptophan synthetase (trpAB) genes appear to be present, suggesting both the production of indole from tryptophan and potentially the synthesis of l-tryptophan through the acquisition of indole (0.25 to 1.1 mM in feces) produced by other gut bacteria (20, 21). Tryptophan auxotrophy may suggest a strategy to limit growth of C. scindens in vivo by inhibiting tryptophanase (22).

FIG 2.

The complete genome of Clostridium scindens ATCC 35704. The genome map describing in order, outside to inside, coding sequences (CDS) in the plus strand, CDS in the minus strand, rRNA genes in the plus strand, rRNA genes in the minus strand, tRNA genes in the plus strand, tRNA genes in the minus strand, CG content plot (windows of 10 kbp, steps of 200 bp), and CG skew plot [(G − C)/(G + C)].

To determine pathways that were expressed during growth in PO4-buffered DM, which may indicate the synthesis or transport of vitamins and other nutrients, we performed RNA-Seq analysis. After removal of rRNA and TruSeq mRNAseq library construction, Illumina HiSeq 4000 sequencing resulted in ∼15 to 18 million reads per sample. The average number of transcripts per million (TPM) among annotated genes (minus tRNA and rRNA) was 273.5 for control samples. Of the 3,656 annotated genes, 1,867 genes were at or below 50 TPM, and 3,486 genes were below 1,000 TPM. Only a dozen open reading frames (ORFs) were above 10,000 TPM (Data Set S1).

Riboflavin was determined to be a necessary vitamin (Fig. S2), and the organism lacks the genes involved in biosynthesis of riboflavin (ribABCGOT) except for two putative riboflavin transporters, ribU1 (4,020 ± 1,257 TPM) and ribU2 (HDCHBGLK_02697; 1,151 ± 411 TPM), whose predicted genes were highly expressed. C. scindens ATCC 35704 does have the gene for riboflavin kinase (ribF; HDCHBLK_03126) required for the conversion of riboflavin to the enzyme cofactors flavin mononucleotide (FMN) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD+), respectively (Data Set S1). Relative to its pantothenic acid requirement, C. scindens ATCC 35704 harbors genes involved in the conversion of pyruvate to α-ketoisovalerate, as well as a gene predicted to encode branched-chain amino acid transferase (llvE), generating l-valine. However, the genes involved in conversion of α-ketoisovalerate to pantoate (panB and panE) and then to pantothenate (panC) are absent in the genome. A gene predicted to encode extracytoplasmic function (ECF)-dependent pantothenate transporter (panT) (HDCHBGLK_02231) is expressed (2,039 ± 166.7 TPM). The complete biosynthetic pathway leading to the conversion of pantothenate to coenzyme A is, however, present in C. scindens ATCC 35704.

C. scindens synthesizes pyridoxal 5′-phosphate synthase and pyridoxal kinase; however, genes involved in de novo synthesis of B6 derivatives are not present in the genome, supporting a nutritional requirement for B6. The lipoic acid salvage pathway genes (lae, lipT1, and lplA) are present but not the biosynthesis genes (lipA and lipB). While biotin was not determined to be necessary, the majority of genes were identified (fabF, fabG, fabZ, fabI, bioH, and bioB), but we were not able to locate dethiobiotin synthase (bioD) or DAPA (7,8-diaminopelargonic acid) aminotransferase (bioA). Thus, the combination of leave-one-nutrient-out analysis with genomics and transcriptomics explains and supports the nutrient requirements of C. scindens ATCC 35704.

Transcriptional response of bile acid-metabolizing genes to CA and DCA.

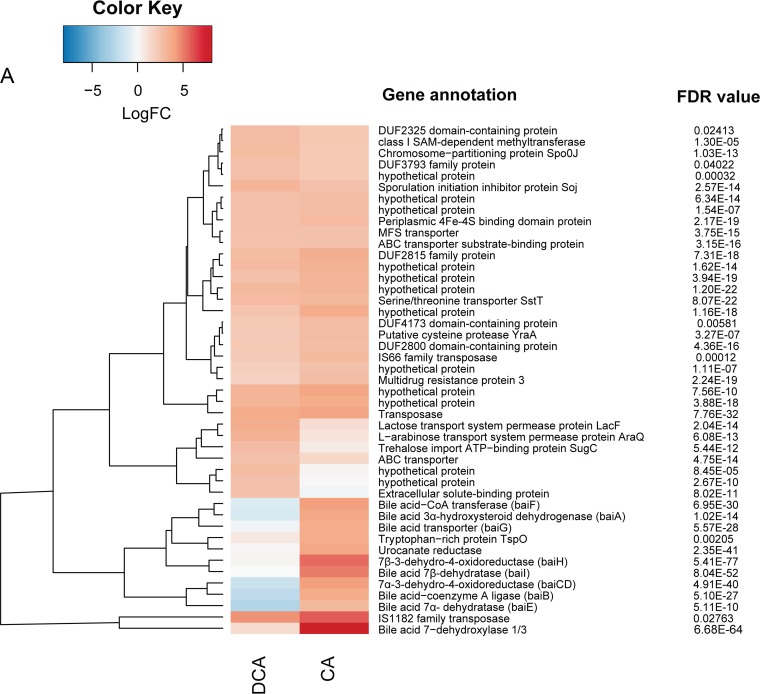

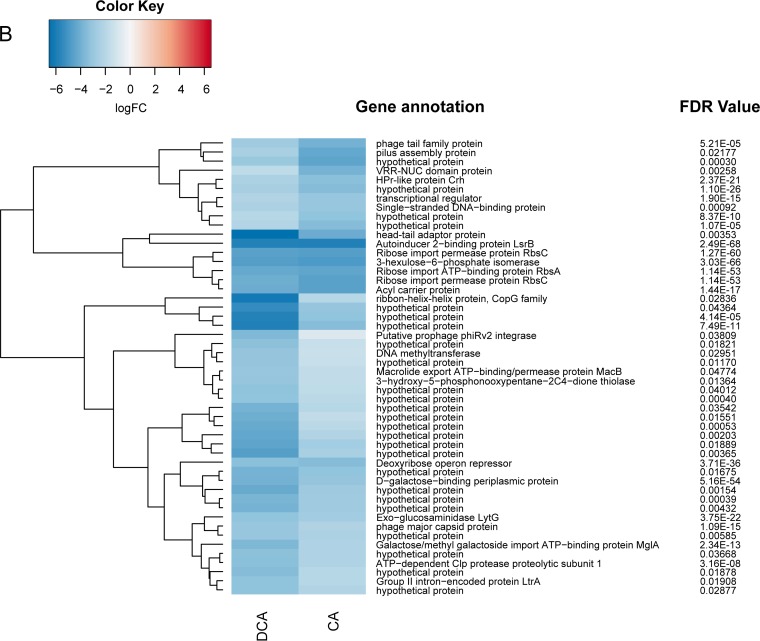

C. scindens ATCC 35704 is a prominent human gut bile acid 7α-dehydroxylating bacterium; however, the global transcriptional response of this bacterium to bile acids has not been reported. Illumina HiSeq sequencing of cDNA derived from total RNA isolated from CA-induced (n = 2) and DCA-induced (n = 2) whole cells of C. scindens ATCC 35704 was performed and compared to results with vehicle control cells (n = 2). We identified 1,430 genes significantly differentially regulated by CA (>1.5-fold change; false discovery rate [FDR], <0.05) with 697 upregulated and 733 downregulated genes (Fig. 3 to 5 and Data Sets S1 and S2). Growth in the presence of DCA resulted in 684 genes significantly upregulated and 1,033 genes downregulated (Fig. 3 to 5 and Data Sets S1 and S3). Multiple-dimensional scaling of control, CA, and DCA transcriptomes showed adequate separation of control and treatment groups (Fig. S3). CA and DCA share 897 differentially expressed genes, while 278 and 207 are unique to CA and DCA, respectively (Fig. S3). Since induction with CA leads to DCA formation during growth, shared genes likely reflect some combination of DCA-induced genes or genes differentially regulated by bile acids generally. Distinguishing between these possibilities will have to await the genetic manipulation of C. scindens.

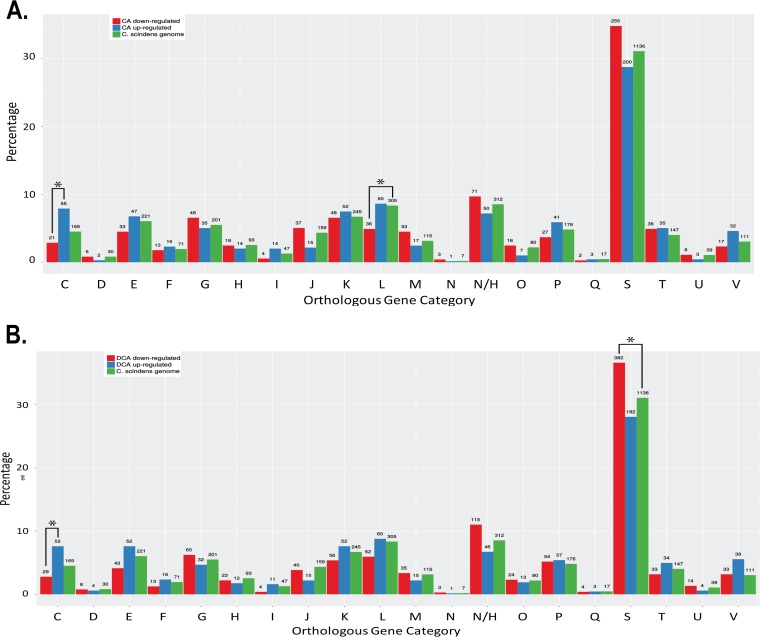

FIG 3.

eggNOG category analysis of RNA-Seq data sets after induction with cholic acid (CA) or deoxycholic acid (DCA) in PO4-buffered defined medium. (A) Orthologous group category of CA-downregulated and CA-upregulated genes relative to number of genes per group in the C. scindens ATCC 35704 genome, as indicated. (B) Orthologous group category of DCA-downregulated and DCA-upregulated genes relative to number of genes per group in the C. scindens ATCC 35704 genome, as indicated. Orthologous group categories displayed on the x axis are as follows: A, RNA processing and modification; B, chromatin structure and dynamics; C, energy conversion; D, cell cycle control and mitosis; E, amino acid metabolism and transport; F, nucleotide metabolism and transport; G, carbohydrate metabolism and transport; H, coenzyme metabolism; I, lipid metabolism; J, translation; K, transcription; L, replication and repair; M, cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis; N, cell motility; NH, no hits/unknown function; O, posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperone functions; P, inorganic ion transport and metabolism; Q, secondary structure; S, function unknown; T, signal transduction; U, intracellular trafficking and secretion; and V, defense mechanisms. Only genes with a P value of <0.05 and a log2FC value greater than −0.58 were included. Statistical significance (*; Bonferroni-corrected P < 0.005) was determined by Fisher’s exact test.

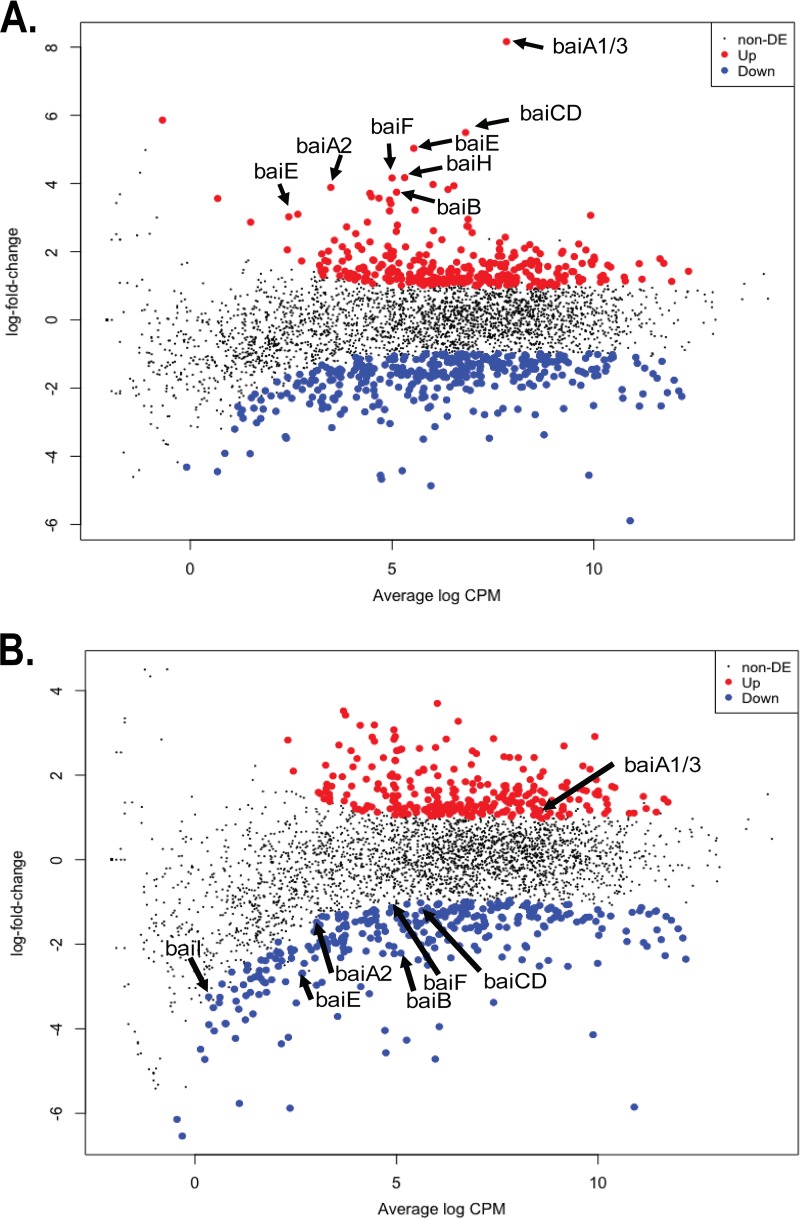

FIG 4.

Log2 fold change versus log counts per million (CPM) scatterplot of Clostridium scindens ATCC 35704 transcriptome data after cultivation in PO4-buffered defined medium with cholic acid (CA) or deoxycholic acid (DCA). (A) Scatterplot of CA data versus the control levels showing upregulated and downregulated genes. (see Data Set S2 in the supplemental material). (B) Scatterplot of DCA data versus control levels (Data Set S3). Labeled arrows represent genes in the bile acid-inducible (bai) operon, which is induced by CA. Upregulated and downregulated genes were defined at a threshold of P < 0.05 and a log2FC value greater than −0.58. non-DE, not differentially expressed.

FIG 5.

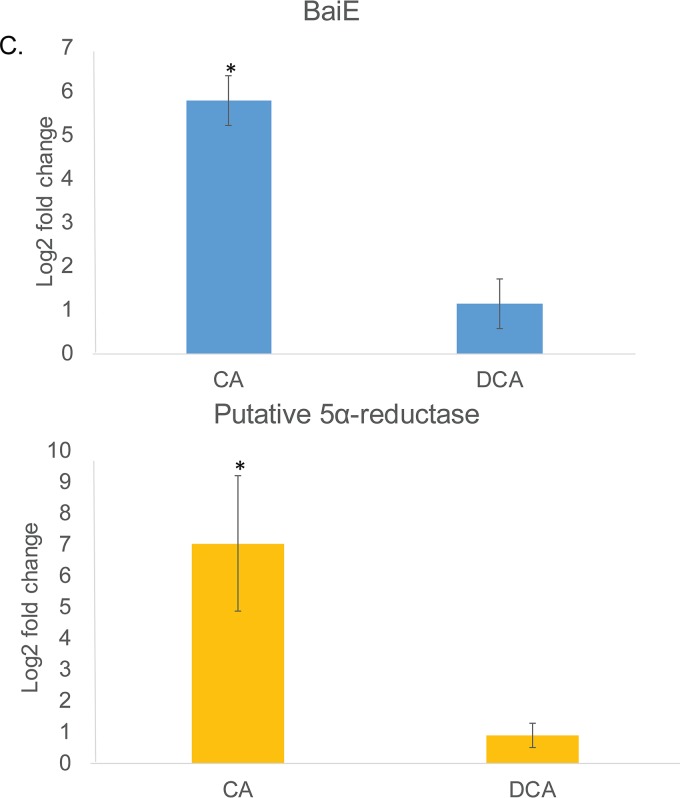

Differential expression of genes from Clostridium scindens ATCC 35704 grown in PO4-buffered defined medium with cholic acid (CA) or deoxycholic acid (DCA). (A) Genes upregulated by CA and DCA relative to the level with DM. (B) Genes downregulated by CA and DCA. False discovery rate (Bonferroni correction) is displayed along with predicted gene annotation. (C) qRT-PCR of the bile acid 7α-dehydratase (baiE gene) and the “urocanate reductase” gene predicted to encode a bile acid 5α-reductase. Results are based on four biological replicates using the 2−ΔΔCT method (reported as standard error of the mean) and normalized relative to the level of the housekeeping gene recA. See Materials and Methods for primer sequences. *, P < 0.05.

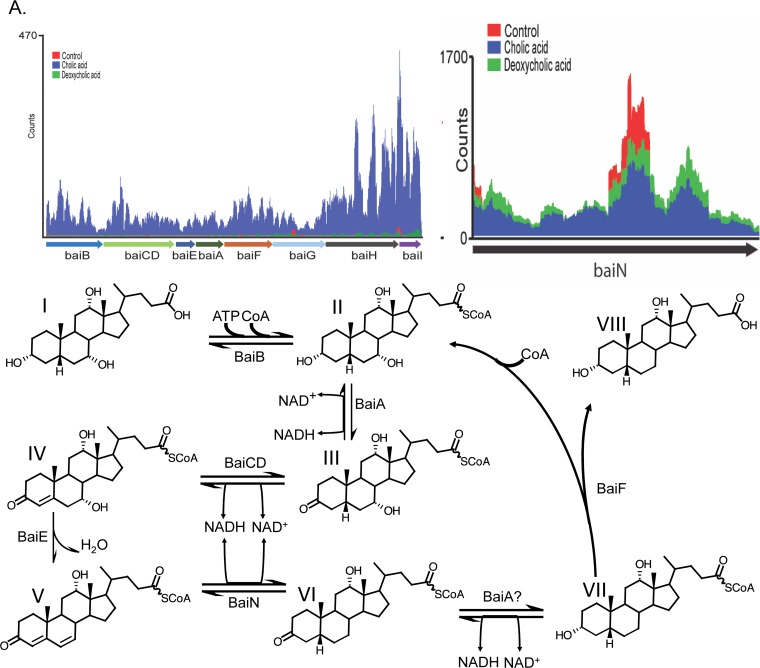

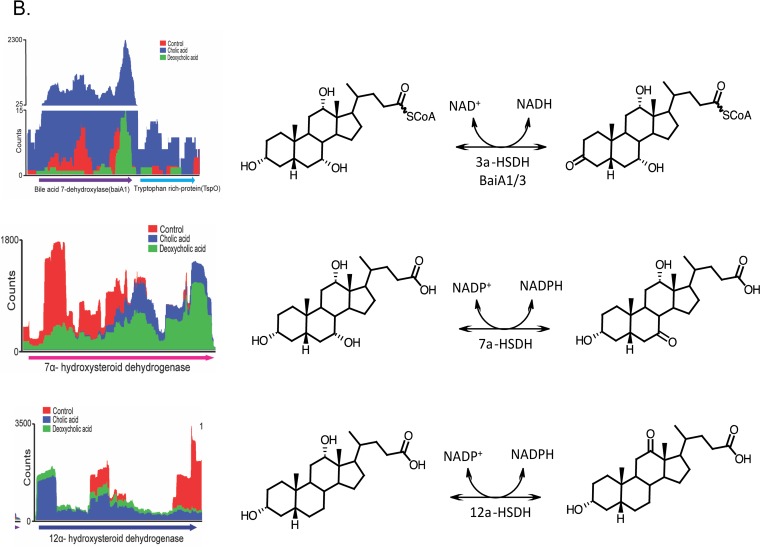

Genes that were significantly upregulated and downregulated were placed into clusters of orthologous groups (COGs) using eggNOG (62). DCA significantly altered transcriptional responses from group C (energy production and conservation; P = 0.001) and group S (unknown function; P = 0.004). CA also significantly altered group C (P = 0.0004) but led to a significant downregulation from group L (replication and repair; P = 0.001) (Fig. 3). As expected, genes encoding bai enzymes were among the most highly expressed genes in the genome in the presence of CA (Fig. 4A and 5A) but were significantly downregulated by DCA, with the exception of the baiA1 (Fig. 4B and 5B). This observation was confirmed by quantitation of baiE transcript by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR), which demonstrated significant induction by CA treatment (5.79 ± 0.56 log2 fold change [log2FC]; P = 0.01) but not by DCA treatment (1.13 ± 0.56 log2FC; P = 0.4) relative to the level of the control (Fig. 5C). Figure 6A shows sequencing coverage across the bai operon as well as the biochemistry of the CA 7α-dehydroxylation pathway. In contrast, the baiN gene (HDCHBGLK_03018), previously shown to encode a flavoprotein involved in the reductive arm of the bile acid 7α-dehydroxylation pathway, was constitutively expressed at an average of 232 ± 63.6 TPM (Data Set S1) (24). The recently reported NADP-dependent 12α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSDH) (HDCHBGLK_00743) characterized from C. scindens ATCC 35704 preferentially converted 12-oxo-LCA to DCA relative to CA metabolites (15). This gene was not differentially regulated by CA or DCA (15). Similarly, a gene encoding NADP-dependent 7α-HSDH, sharing 98% amino acid identity with NADP-dependent 7α-HSDH (HDCHBGLK_01258) characterized from C. scindens VPI 12708 (25), was also constitutively expressed at an average of 640 ± 121.5 TPM (Fig. 6B).

FIG 6.

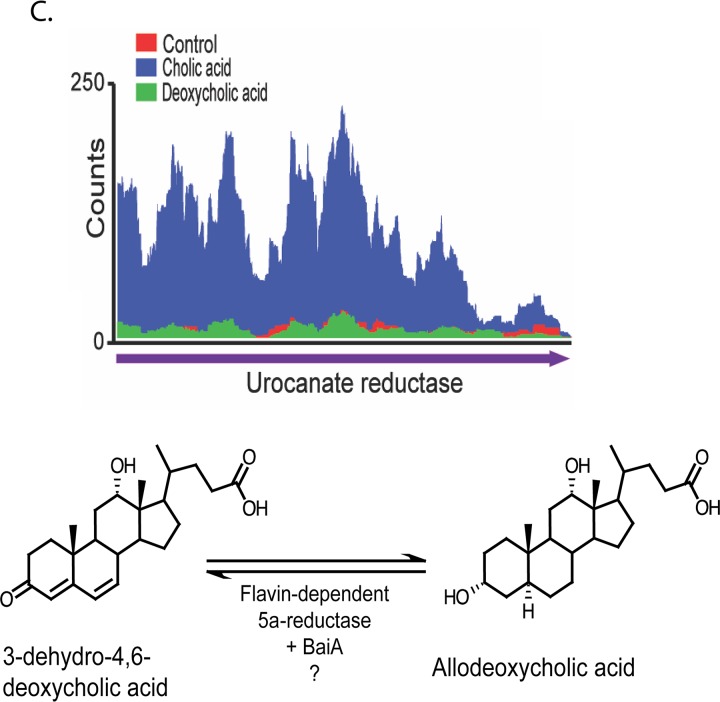

Mapped RNA-Seq counts against genes involved in bile acid metabolism by Clostridium scindens ATCC 35704. (A) Reads mapped against the polycistronic bai operon, along with biochemistry of cholic acid 7α-dehydroxylation. Metabolites are as follows: I, cholic acid; II, cholyl∼CoA; III, 3-dehydrocholyl∼CoA; IV, 3-dehydro-4-cholyl∼CoA; V, 3-dehydro-4,6-deoxycholyl∼CoA; VI, 3-dehydro-deoxycholyl∼CoA; VII, deoxycholyl∼CoA; VIII, deoxycholic acid. (B) Reads mapped to bile acid 3α-, 7α-, and 12α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase genes. The CA-induced TspO gene predicted to be involved in bile acid metabolism is located downstream of the baiA gene. (C) Reads mapped to a CA-inducible gene encoding a predicted flavoprotein hypothesized to generate allo-(5α)-deoxycholic acid. Conversion from compound V to allodeoxycholic acid predicted to be in two steps, with the BaiA1 catalyzing the final NADH-dependent reductive step.

The expression of a gene predicted to encode tryptophan-rich protein TspO was significantly upregulated by CA (3.56 log2FC; P = 6.8E−04; FDR = 0.003) but downregulated, although not statistically significantly, by DCA (0.7 log2FC; P = 0.53; FDR = 0.69) (Fig. 5A and Data Sets S2 and S3). We previously reported a gene encoding a TspO/mitochondrial benzodiazepine receptor (MBR) family protein in C. scindens VPI 12708 downstream and on the opposite strand of the monocistronic baiA2 and upstream of a bai promoter region and the baiJKL operon (26). While the role of the TspO/MBR family in bile acid metabolism (if any) is currently unknown, this protein has been shown previously to function in the import and metabolism of steroids and, potentially, in the prevention of oxidative stress (27). The position of the gene encoding the TspO/MBR family protein, downstream of baiA, and induction by CA but not DCA may indicate that this gene is involved in bile acid metabolism or has an important function during high intracellular concentrations of bile acid intermediates and end products (Fig. 5A and 6B).

Similarly, a gene encoding a predicted pyridine nucleotide-dependent flavoprotein (urocanate reductase, urdA; HDCHBGLK_03451) is upregulated by CA (3.82 log2FC; P = 1.61E−28; FDR = 5.35E−26) but not by DCA (Fig. 5A). This observation was confirmed by qRT-PCR demonstrating significant induction by CA treatment (7.03 ± 2.15 log2FC; P = 0.002) but not by DCA treatment (0.9 ± 0.38 log2FC; P = 0.58) (Fig. 5C). The predicted urdA gene product shares 47.5% amino acid identity with the baiJ gene product (62-kDa gene product) encoding a predicted flavoprotein in C. scindens VPI 12708, which is part of a polycistronic operon that includes the baiK gene. The baiK gene encodes a bile acid coenzyme A (CoA) transferase; however, the functions of the remaining genes are currently unknown (26). Previous reports by Hylemon et al. (1991) identified allo-deoxycholic acid (5α-reduced) as a cholic acid-inducible side product of bile acid 7α-dehydroxylation (28). The finding that allo-bile acids are formed leads to the prediction that at least two genes encoding stereospecific flavin-dependent oxidoreductases encoding bile acid 5α-reductase and bile acid 5β-reductase. We recently reported an NAD(H)-dependent flavoprotein, baiN, which catalyzes two steps in the reductive arm of the bile acid 7α-dehydroxylation pathway (3-dehydro-4,6-DCA → 3-dehydro-4-DCA → 3-dehydro-DCA) (24). The baiN gene, encoding a bile acid 5β-reductase, is not differentially regulated by bile acids but is instead constitutively expressed (∼200 TPM). It is intriguing to identify another gene that is predicted to catalyze C=C bond formation (Fig. 6C) but that is differentially regulated by primary bile acids. Further research is needed to determine the role of urdA, particularly as a bile acid 5α-reductase.

Classical bile acid efflux permeases were studied in Escherichia coli, encoded by the acrAB genes (29) whose homologs are absent in the genome of C. scindens ATCC 35704. There are currently no candidates for bile acid efflux permeases in bile acid 7α-dehydroxylating bacteria, which may represent a potential drug target to inhibit growth of these bacteria during chronic DCA excess. Growth in the presence of bile acids resulted in significant expression of genes predicted to encode membrane-spanning efflux permease proteins (Table S2). A few candidates include the putative multidrug export permease ygaD (HDCHBGLK_00878; 2.14 log2FC; FDR = 5.0E−04), putative ABC transporter yxlF (HDCHBGLK_01721; 1.83 log2FC, FDR = 2.65E−08), and multidrug-resistance protein 3 (HDCHBGLK_02921; 1.80 log2FC; FDR = 2.58E−09). Table S2 lists expression levels of numerous genes (>0.58 log2FC; <0.05 FDR) predicted to play a role in response to bile acid stress, consistent with previous studies (30–38). Future studies should address the identity and number of bile acid export proteins and the importance that these and other proteins have in the growth and bile acid metabolism of C. scindens.

Carbohydrate screening and end product analysis of glucose metabolism by C. scindens.

Conversion of primary to secondary bile acids by C. scindens results in a net 2-electron reduction which is flavin and pyridine nucleotide dependent (39). Thus, primary bile acid metabolism provides electron acceptors, which are coupled to the fermentation of sugars and potentially other substrates as well in vivo. However, a basic understanding of fermentable sugars and the types and amounts of end products formed during fermentation by C. scindens is lacking. We thus, examined the ability of C. scindens to metabolize different carbohydrates as well as their genomic basis and expression under chemically defined culture conditions, providing key insights into the physiology of this bacterium. Replacement of glucose in DM with various simple and complex carbohydrates was performed to determine growth by C. scindens ATCC 35704. Out of 40 carbohydrates examined, only 6 monosaccharides (glucose, fructose, mannose, galactose, ribose, and xylose), 2 sugar alcohols (dulcitol and sorbitol), and 1 disaccharide (lactose) were growth supportive (Table S1). Carbohydrate metabolism therefore appears to be largely restricted to a few monosaccharides and the disaccharide lactose.

Analysis of the annotated genome provided confirmation of observed sugar fermentation profiles. Genes involved in lactose metabolism were located in the genome sequence. Lactose is cleaved by β-galactosidase (bglY; HDCHBGLK_02011), converted to 1-phospho-galactose by galactokinase (HDCHBGLK_01716), and then transferred to UDP-α-glucose by UDP-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase (HDCHBGLK_01717), forming UDP-α-d-galactose. The last is then converted to UDP-α-d-glucose by UDP-glucose 4-epimerase (galE; HDCHBGLK_02011) and aldose-1-epimerase (galM; HDCHBGLK_03553), while lacF (HDCHBGLK_02016) and lacG (HDCHBGLK_02017) are located downstream of lacZ and galE. Upstream of galE is a cryptic high-molecular-weight β-galactosidase (HDCHBGLK_02009). As expected, the expression levels (as TPM) of genes predicted to hydrolyze lactose and metabolize galactose were low, given that glucose, rather than lactose, was present in DM (Data Set S1).

l-Xylose is also fermented by C. scindens ATCC 35704 (Table S1). Genes predicted to encode a xylose-importing ATP-binding protein (xylG; HDCHBGLK_01674) and xylulose kinase (HDCHBGLK_00721) were located in the genome, as was a gene for a predicted mannose-6-phosphate isomerase (HDCHBGLK_01361). The sugar alcohol sorbitol is also metabolized (Table S1), and we located two genes encoding putative sorbitol dehydrogenases (HDCHBGLK_00843; HDCHBGLK_01676). While the complex carbohydrates tested in our study were not metabolized, C. scindens ATCC 35704 does have the genes for a predicted neopullulanase 1 (HDCHBGLK_01304) as well as an acetylxylan esterase (HDCHBGLK_03158), suggesting that metabolism of certain complex dietary or host-derived carbohydrates cannot be ruled out.

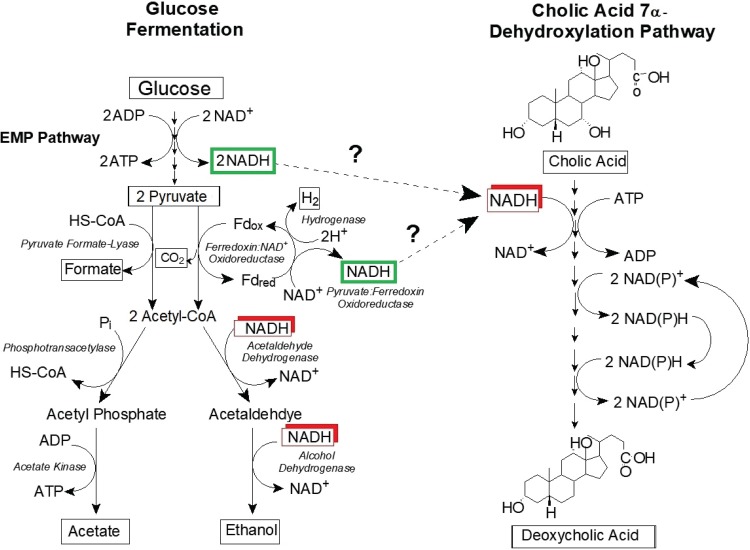

Next, we determined the end products of glucose metabolism in PO4-buffered DM and in PO4-buffered MM (Table 1). After 24 h of growth in PO4-buffered DM, glucose was not detected, indicating that C. scindens ATCC 35704 completely consumed the glucose (19.4 mM). The major end products formed were ethanol (24.6 mM), acetate (10.7 mM), formate (6.3 mM), and H2 (16.9 mM), whereas other products were produced in very negligible (< 1 mM) amounts. Based on substrate-product profiles of glucose-grown cells, carbon recovery was 72% and may be attributed to the fact that CO2 levels and biomass carbon production were not determined. In PO4-buffered MM, C. scindens ATCC 35704 converted glucose essentially to the same products as cells grown in PO4-buffered DM. However, the concentrations of most end products in PO4-buffered MM were lower due to the decreased glucose consumption. Therefore, to compare cells grown under these different conditions, the ratio of product formed (mM) per glucose (mM) consumed was used. On this basis, in PO4-buffered DM and in PO4-buffered MM, cells exhibited similar substrate-product profiles (Table 1). It is worth noting that as the culture conditions became more nutritionally demanding (DM → MM), ethanol production increased slightly while formate levels decreased.

TABLE 1.

Substrate-end product profiles of C. scindens ATCC 35704 grown in PO4-buffered defined medium and PO4-buffered minimal mediuma

| Substrate consumed or product formedc | PO4-buffered defined medium (mM)b | PO4-buffered minimal medium (mM)b |

|---|---|---|

| Substrate consumed | ||

| Glucose | 19.4 ± 2.7 | 10.9 ± 5.5 |

| Product formed | ||

| Ethanol | 24.6 ± 6.6 (1.27) | 22.0 ± 8.4 (2.02) |

| Succinate | 0.8 ± 0.0 (0.04) | 0.3 ± 0.0 (0.03) |

| Lactate | 0.4 ± 0.0 (0.02) | 0.4 ± 0.0 (0.04) |

| Formate | 6.3 ± 0.4 (0.32) | 0.5 ± 0.5 (0.05) |

| Acetate | 10.7 ± 0.9 (0.55) | 4.2 ± 1.5 (0.39) |

| Isobutyrate | 0.1 ± 0.2 (0.01) | 0.8 ± 0.6 (0.07) |

| Butyrate | ND | 0.1 ± 0.1 (0.01) |

| Isovalerate | 0.4 ± 0.1 (0.02) | 0.3 ± 0.1 (0.03) |

| Valerate | ND | ND |

| H2 | 16.9 ± 2.0 (0.87) | 7.2 ± 1.7 (0.37) |

PO4-buffered defined medium and PO4-buffered minimal medium were DM and MM, respectively, with the following modifications: NaHCO3 was replaced by a phosphate buffer (KH2PO4 [2.6 g/liter] and K2HPO4 [5.4 g/liter]); CO2 was replaced by dinitrogen (N2) or argon (Ar) gas as the initial gas phase; and glucose, routinely added prior to autoclaving, was replaced with glucose (22 mM) added to tubes of sterile media from an anoxic, filter-sterilized glucose stock solution.

Values represent the differences between values at time zero (at the time of inoculation) and values at the time when maximum growth was achieved and are the means of triplicate tubes ± standard deviations. Parenthetical values are the amount of product formed (mM) per amount of glucose (mM) consumed. ND, not detected.

Carbon recovery was 72% and 93% in PO4-buffered defined medium and PO4-buffered minimal medium, respectively.

Relative to ethanol formation by C. scindens ATCC 35704, pyruvate is converted to acetyl-CoA by the enzyme pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase (PFOR), which also yields CO2 and reduced ferredoxin (FDred). The reoxidation of FDred is then achieved by one of two ways, reduction of NAD+ via ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase or conversion to H2 by hydrogenase. H2 was detected in the headspace gas of cultures (Table 1) and is predicted to be generated by a highly expressed ferredoxin-dependent group B [FeFe] hydrogenase (HDCHBGLK_03096; 1,013.1 ± 308.2 TPM) (40). Another gene encoding predicted ferredoxin-dependent H2-evolving [FeFe] hydrogenase (group A) was expressed at a much lower level (HDCHBGLK_00634; 72.6 ± 11.6 TPM). RNA-Seq analysis determined that a gene encoding predicted bifunctional aldehyde-alcohol dehydrogenase (adhE; HDCHBGLK_00499) was highly expressed (2,246.8 ± 434.5 TPM). Regarding acetate formation, genes involved in the conversion of acetyl-CoA to acetyl phosphate (phosphotransacetylase; HDCHBGLK_02911; 842.2 ± 140.9 TPM) and to acetate (acetate kinase; HDCHBGLK_02912; 221.0 ± 83.7 TPM) were expressed. Formate was also generated, and genes encoding putative formate acetyltransferase (HDCHBGLK_02831; 496.8 ± 72.6 TPM) and pyruvate formate-lyase-activating enzyme (HDCHBGLK_02832; 803.1 ± 308.4 TPM) are expressed in DM. Although glucose is the only carbohydrate present, the presence of bile acids led to a noticeable increase in gene expression levels of predicted transporters of lactose, trehalose, and arabinose, indicating that with C. scindens ATCC 35704 sugar preference may be altered in the presence of CA and DCA (Fig. 5A).

Genomic potential for amino acid fermentation.

As a final note, Clostridium spp. are also recognized as unique for their ability to generate ATP through substrate-level phosphorylation via oxidation of one amino acid followed by the reduction of another in what is known as Stickland fermentation (41, 42). A Western diet high in animal protein and fat increases both the concentration of bile acids and the concentration of amino acids available for fermentation (43). Amino acids as electron donors may be coupled to bile acids as electron acceptors (e.g., 3-dehydro-4,6-DCA) via NADH. Given the expression levels in PO4-buffered DM, the genomic potential is present for amino acid fermentations in C. scindens ATCC 35704, including genes for proline reductase and glycine reductase. The glycine cleavage pathway is also present, suggesting that l-glycine oxidation may be coupled to l-proline or l-glycine reduction (Table S3). While these results indicate that C. scindens ATCC 35704 may utilize Stickland fermentation, further work will be needed both in vitro and in vivo to determine the contribution of amino acids as electron donors and acceptors.

DISCUSSION

Several decades of research have focused on the molecular biology and enzymology of the bai regulon in Clostridium scindens from a reductionist point of view (3, 4); however, global responses to bile acids by strains of this species have not been determined. Secondary bile acid metabolites from C. scindens ATCC 35704 were recently shown to regulate hepatic natural killer (NKT) cell accumulation, affecting growth of liver tumors (44). Another study showed that DCA promotes the senescence-associated secretory phenotype in obesity-associated hepatocellular carcinoma, with bacterial operational taxonomic unit 154 (OTU-154) closely related to C. hylemonae or C. scindens in Clostridium cluster XIVa representing 0.5% of the total fecal microbiome (45). A recent analysis of fecal microbiota of patients with (n = 233) and without (n = 547) adenomas identified an increased shift in secondary bile acid biosynthesis in adenoma patients (46). This is consistent with decades of literature implicating secondary bile acids in colorectal cancer (47). Gallstone patients have been shown to harbor >42-fold-higher levels of bile acid 7α-dehydroxylating bacteria than control patients (48). Antibiotic treatment reduced cholesterol saturation in gallstone patients by targeting 7α-dehydroxylating bacteria and formation of DCA (49). Understanding how C. scindens responds to CA and DCA may indicate potential intervention strategies to reduce toxic and cancer-promoting secondary bile acids such as DCA (4, 43, 50).

On the other hand, formation of DCA may be important in precluding the growth of pathogens such as Clostridium difficile and may indicate acute uses of bile acid 7α-dehydroxylating bacteria as probiotics (51–54). Indeed, recent work by Kang et al. (2018) demonstrated that the interaction between C. scindens and C. difficile involves not only secondary bile acids but also tryptophan-derived antibiotics (54). Surprisingly, very little is still known about the biology of the few gut bacteria capable of generating secondary bile acids. The completion of the genome of C. scindens ATCC 35704 and transcriptomic analysis in defined and minimal media are expected to hasten identification of genes involved in formation of peptide antibiotics and further integrate bile acid metabolism with fermentative pathways and adaptations to bile salt stress.

An important contribution of the present work is both the determination of the nutritional requirements for C. scindens ATCC 35704 and the integration of genomic and transcriptomic data with the physiology of this bacterium. In the present study, we report genome-wide transcriptomic analysis of bile acid induction by a bile acid 7α-dehydroxylating bacterium. Our data indicate that complex and bile acid-specific transcriptional responses are determined by the presence or absence of the 7α-hydroxyl group. Addition of CA to the growth medium resulted in a several-log fold change in the genes of the bai regulon, which were among the most highly upregulated genes. DCA, which differs from CA only in the absence of the 7α-hydroxyl group, did not induce the bai regulon. This is consistent with previous reports of bile acid 7α-dehydroxylating activity and induction of the baiB gene (55).

The first and last oxidative steps in the bile acid 7α-dehydroxylation pathway involve oxidation/reduction of the C-3 oxygen in an NAD(H)-dependent reaction (3, 4, 56). Previous work before genome sequences were available suggested that there were three copies of the baiA gene in C. scindens: the baiA2 is encoded within the baiBCDEAFGHI operon and there are two additional mono-cistronic copies, baiA1 and baiA3 (56). Completion of the genome of C. scindens ATCC 35705 reveals that there are only two copies of the baiA gene encoding bile acid 3α-HSDH, the baiA2 gene and what is now referred to as the baiA1, distant from the bai operon, with its own conserved bai promoter region (56). Kinetic analysis suggests that BaiA2 and BaiA1 may function in both the oxidative and reductive arms of the bile acid 7α-dehydroxylating pathway, converting CA∼CoA to 3-dehydro-CA∼CoA and 3-dehydro-DCA∼CoA to DCA∼CoA, respectively (14). Interestingly, our transcriptomic analysis indicated that while the baiA2 gene, coexpressed on the polycistronic bai operon, was downregulated by DCA, baiA1 was significantly increased (Fig. 4 and 5). This may suggest that the baiA1 gene product is involved in the final reductive step in the pathway; however, it is still unclear if there are additional genes encoding enzymes capable of converting 3-dehydro-DCA(∼SCoA) to DCA(∼SCoA). Development of a genetic system for C. scindens and targeting of the baiA genes with addition of 3-dehydro-CA to whole cells will allow this question to be properly addressed.

Intriguingly, genes encoding putative TspO and urocanate reductase were significantly upregulated by CA but not by DCA (Fig. 6C). While their roles in bile acid metabolism are unclear, it is interesting that TspO homologs are membrane-spanning proteins which are involved in enzymatic metabolism or transport of steroids and benzodiazopene drugs (27). We recently reported a gene encoding a flavin-dependent bile acid 5β-4,6-reductase (baiN) involved in converting the stable 3-dehydro-4,6-DCA/LCA intermediate (following 7α/β-dehydroxylation) to 3-oxo-DCA (5β-A/B ring orientation) (24). However, previous reports established the CA-inducible expression of a 5α-4,6-reductase which results in formation of allo-DCA (5α-A/B ring orientation) (28, 55). Future research will be required to elucidate the function of the proteins encoded by these newly identified CA-inducible genes.

The bile acid 7α-dehydroxylation process is a series of oxidation and reduction reactions which require coenzymes and cofactors (3). Transcriptomic analysis of CA-induced whole cells of C. scindens suggests an intimate linkage between the growth-limiting nutritional requirements and bile acid 7α-dehydroxylation process in C. scindens ATCC 35704 (Fig. 7). Indeed, tryptophan is a precursor for cofactor NAD+ required in both oxidative and reductive steps, pantothenate is a core precursor for cofactor coenzyme A (CoA) added by the BaiB and transferred by BaiF/BaiK, and pyridoxal phosphate is a vital cofactor in amino acid and carbohydrate metabolism which links electron donor and bile acid acceptor. Equally important is the identification of numerous CA- and DCA-induced transmembrane efflux pumps, some of which may be involved in transporting DCA out of the cell (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The current study thus represents an important advance in understanding the biology of C. scindens ATCC 35704 and the response of this important bile acid 7α-dehydroxylating bacterium to bile acids.

FIG 7.

A proposed model for the coupling of glucose metabolism and bile acid 7α-dehydroxylation by Clostridium scindens ATCC 35704. Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas (EMP) pathway.

Conclusion.

The current study defined the nutritional requirements of C. scindens ATCC 35704 and integrated genomic and transcriptomic data sets that support the findings that tryptophan, pyridoxal phosphate, pantothenic acid, and riboflavin are required nutrients. The bai regulon was highly expressed in the presence of CA but not DCA, consistent with previous studies on bile acid induction. Novel candidates for bile acid-metabolizing enzymes and efflux pumps were identified. Transcriptome analysis suggests that C. scindens ATCC 35704 upregulates genes involved in stress, including cell wall metabolism, DNA repair, expression of chaperones, and multidrug efflux pumps. The current work will facilitate future understanding of the linkage between sugar or amino acid fermentation, nutritional requirements, and bile acid metabolism by C. scindens, which will be important in understanding the role of diet and microbial metabolic interactions in health and disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

CA and DCA were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Carbohydrates were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH, USA), Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium), and Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). All other chemicals were of the highest possible purity and were purchased from Fisher Scientific.

Bacterial strain and growth conditions.

Clostridium scindens ATCC 35704, obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA), was maintained in butyl rubber-stoppered, aluminum crimp-sealed culture tubes (18 by 150 mm; series 2048 [Bellco Glass, Inc., Vineland, NJ, USA]; ∼27.2-ml stoppered volume at 1 atm [101.29 kPa]) containing anaerobic brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (15).

Unless noted otherwise, the defined medium (DM) contained the following (in milligrams per liter): glucose, 4,500; NaCl, 500; (NH4)2SO4, 500; KCl, 250; KH2PO4, 250; MgSO4·7H2O, 25; sodium nitrilotriacetate, 3; MnSO4·H2O, 1; FeSO4·7H2O, 0.2; Co(NO3)2·6H2O, 0.2; ZnCl2, 0.2; NiCl2·6H2O, 0.1; H2SeO3, 0.1; CuSO4·5H2O, 0.02; AIK(SO4)2·12H2O, 0.02; H3BO3, 0.02; Na2MoO4·2H2O, 0.02; Na2WO4·2H2O, 0.02; resazurin, 1; vitamins (biotin, 0.2; folic acid, 0.2; pyridoxal HCl, 0.2; lipoic acid, 0.5; nicotinic acid, 0.5; d-pantothenic acid, 0.5; p-aminobenzoic acid, 0.5; riboflavin, 0.5; thiamine, 0.5; cyanocobalamin, 0.5); and amino acids (l-alanine, l-arginine·HCl, l-asparagine·H2O, l-aspartic acid, l-cystine, l-glutamic acid, l-glutamine, l-glycine, l-histidine, l-isoleucine, l-leucine, l-lysine, l-phenylalanine, l-proline, l-methionine, l-serine, l-threonine, l-tryptophan, l-tyrosine, and l-valine; 40 mg each). The medium pH was adjusted to 7, and NaHCO3 (7.5 g/liter) was added. DM was prepared anaerobically by boiling the medium under 100% CO2 and, after cooling, by adding Na2S·9H2O (0.5 g/liter) and dispensing the medium (10 ml) under 100% CO2 into culture tubes. Tubes were then crimp sealed and autoclaved. UM was DM with 0.1% yeast extract added. The initial pH (before inoculation) of DM and UM approximated 6.8.

Unless noted otherwise, the minimal medium (MM) contained the following (in milligrams per liter): glucose, 4,500; NaCl, 500; (NH4)2SO4, 500; KCl, 250; KH2PO4, 250; MgSO4·7H2O, 25; sodium nitrilotriacetate, 3; MnSO4·H2O, 1; FeSO4·7H2O, 0.2; Co(NO3)2·6H2O, 0.2; ZnCl2, 0.2; NiCl2·6H2O, 0.1; H2SeO3, 0.1; CuSO4·5H2O, 0.02; AIK(SO4)2·12H2O, 0.02; H3BO3, 0.02; Na2MoO4·2H2O, 0.02; Na2WO4·2H2O, 0.02; resazurin, 1; vitamins (pyridoxal HCl, 0.2; d-pantothenic acid, 0.5; riboflavin, 0.5); and an amino acid (l-tryptophan, 40 mg). The medium pH was adjusted to 7, and NaHCO3 (7.5 g/liter) was added. MM was prepared anaerobically by boiling the medium under 100% CO2 and, after cooling, by adding Na2S·9H2O (0.5 g/liter) and dispensing the medium (10 ml) under 100% CO2 into culture tubes. Tubes were then crimp sealed and autoclaved. The initial pH (before inoculation) of MM approximated 6.8.

PO4-buffered DM and PO4-buffered MM were DM and MM, respectively, with the following modifications for both: NaHCO3 was replaced by a phosphate buffer (KH2PO4 [2.6 g/liter] and K2HPO4 [5.4 g/liter]), CO2 was replaced by dinitrogen (N2) or argon (Ar) gas as the initial gas phase, and glucose, routinely added prior to autoclaving, was replaced with glucose added to tubes of sterile medium from an anoxic, filter-sterilized glucose stock solution. It should be noted that PO4-buffered medium was used to facilitate substrate and end product determinations as well as transcriptomic analyses.

In all experiments, growth was initiated by injecting 0.5 ml of inoculum (late log-/early-stationary-phase cultures) into tubes of sterile medium with sterile 23-gauge needles and 1-ml syringes. All inoculated tubes were incubated vertically without shaking and in the dark at 37°C; growth was measured over time as the optical density (OD) at 600 nm using a spectrophotometer (Spectronic Instruments, Inc., Rochester, NY, USA); the optical path width (inner diameter of culture tubes) was 1.6 cm. Uninoculated culture media served as references. A culture medium was considered growth supportive if OD values of cultures in the medium after three sequential transfers were ≥0.05. All OD values reported are the means of duplicate cultures or experiments.

Nutritional requirements.

To determine amino acid and vitamin requirements for C. scindens ATCC 35704, the leave-one-amino-acid-group-out and leave-one-vitamin-out approaches were used, respectively. First, amino acids were divided into six groups based on known interconversions: (i) glutamate group (Glu grp; glutamine, glutamic acid, proline, and arginine), (ii) serine (Ser) group (serine, glycine, and cystine), (iii) aspartate (Asp) group (aspartate, asparagine, methionine, lysine, threonine, and isoleucine), (iv) pyruvate (Pyu) group (alanine, valine, and leucine), (v) aromatic (Aro) group (tryptophan, tyrosine, and phenylalanine), and (vi) histidine (His) group (histidine). Six amino acid group-deficient versions of DM (i.e., each version of DM had one of the six amino acid groups omitted) were inoculated with active DM cultures. Amino acid group-deficient versions of DM that supported growth indicated which amino acids were not required and were eliminated from further testing. Next, each amino acid from a growth-supportive group was tested individually in DM, which contained the remaining amino acids from the other growth-supportive groups; growth under these conditions indicated which amino acid(s) was required.

For vitamin requirements, 10 vitamin-deficient versions of DM (i.e., each version of DM had 1 of the 10 vitamins omitted) were inoculated with active DM cultures; the absence of growth under these conditions indicated which vitamin(s) was required.

Carbohydrate screening.

To determine which carbohydrates were growth supportive, glucose in DM was replaced with individual (different) carbohydrates. Stock solutions (10%) of monosaccharides (d-glucose, d-fructose, d-mannose, d-galactose, l-rhamnose, l-sorbose, l-arabinose, d-ribose, and d-xylose), sugar alcohols (d-lactitol, myo-inositol, d-mannitol, d-sorbitol, d-xylitol, erythritol, and glycerol), disaccharides (cellobiose, lactose, lactulose, maltose, melibiose, sucrose, and trehalose), trisaccharides (melezitose and raffinose), polysaccharides (polydextrose and starch), and synthetic sweeteners (saccharin and sucralose) were prepared in tubes using distilled, reverse osmosis (DRO) water, stoppered and crimp sealed, degassed by sparging and flushing the headspace gas with Ar gas, and sterilized by autoclaving. Due to solubility issues, some substrates were prepared as 3.85% stock solutions: sugar alcohols (d-adonitol and dulcitol), polysaccharides (dextrin, glycogen, inulin, mucin, pectin, and stachyose), and glycosides (amygdalin, esculin, and salicin). Stock solutions (10% or 3.85%) were added (0.2 ml) via sterile needles and syringes to tubes of DM (7 ml) to achieve initial substrate concentrations (after inoculation) of 0.25% or 0.1%, respectively.

TLC of bile acids.

For analysis of bile acids in cultures and in standards prepared in sterile media, thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was used. Samples of stationary-phase cultures were removed aseptically, and bile acids were extracted immediately, or samples were stored at −20°C until extracted. For bile acid extraction, a 1-ml sample of a culture or bile acid standard was transferred to duplicate microcentrifuge tubes (500 µl per tube), and 50 µl of 3 N HCl and 500 µl of ethyl acetate were added to each tube. Tubes were capped, vortexed, and spun for 1 min at 16,000 × g. The organic phase (top layer) was removed from each tube and transferred to a 20-ml glass scintillation vial. Steps from the addition of ethyl acetate to the collection of the organic phase were repeated for each sample. The collected (pooled) organic phase was dried at room temperature under N2. Methanol (100 μl) was added to each vial, and methanol-dissolved extracts were spotted (50 μl) onto TLC plates (20- by 20-cm AL Sil G, 250 μm thick, non-UV; Macherey-Nagel, Duren, Germany). Nonradiolabeled bile acids separated by TLC were visualized as recently described (15). To visualize 24-14C-labeled bile acids, TLC plates containing bile acid intermediates were placed on Kodak Biomax MS film overnight and developed as described previously (55). Bile acids were identified by comparing Rf values of bile acid standards to those of bile acids detected in cultures.

HPLC.

The following high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) equipment and conditions were used for the analysis of glucose and organic acids in standards and in PO4-buffered DM and PO4-buffered MM cultures: Beckman Gold System (125 solvent module, model 166 variable wavelength detector, Jasco RI-1530 refractive index [RI] detector, Eppendorf CH-30 column heater, model 508 autosampler, and 32 Karat software, version 5); Aminex HPX-87H (300-mm long) analytical column (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA); 0.01 N H2SO4 solvent; solvent flow rate of 0.6 ml/min; column temperature of 55°C; injection size of 20 μl; detection by UV (210 nm) for short-chain organic acids or RI for glucose; and run time of 45 min. Culture fluids were clarified by microcentrifugation and microfiltration and stored at −20°C until analyzed. All concentrations were expressed on a millimolar basis.

GC.

The following gas chromatography (GC) equipment and conditions were used for the analysis of hydrogen (H2) gas analysis in standards and in PO4-buffered DM and PO4-buffered MM cultures: Thermo Fisher Trace 1310 gas chromatograph (thermal conductivity detector and Dionex chromeleon, version 7.1.2.1478, software); stainless steel column (2 mm by 2 m) containing a molecular sieve (13 by 60/80; Restek, Bellefonte, PA, USA); 100% Ar carrier gas; carrier gas flow rate of 20 ml/min; 150°C injection port; 60°C column oven,; 175°C detector; injection size of 100 μl; run time of 2 min. Before chromatographic analysis, headspace gas volume was measured (in millibars) with a TensioCheck (Tensio-Technik, Geisenheim, Germany) manometer. Hydrogen (H2) solubility was calculated from a standard solubility table (57), and the amount of gas produced was calculated by considering both gas and liquid phases.

PacBio genome sequencing of Clostridium scindens ATCC 35704.

Genomic DNA was isolated as previously described (23) with some modifications. Chemical lysis was performed, and pipetting steps were omitted after gentle phenol and then phenol-chloroform-acetic acid washes. DNA was further purified by a genomic tip 100 column according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The genome of C. scindens ATCC 35704 was sequenced by a Pacific Biosciences RSII instrument after high-molecular-weight genomic DNA (> 40 kb) was submitted to the Great Lakes Genomics Center, University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee. A standard Pacific Biosciences large-insert library preparation was performed. DNA was fragmented to approximately 20 kb using Covaris G tubes. Fragmented DNA was enzymatically repaired and ligated to a PacBio adapter to form the SMRTbell template. Templates (>10 kb) were size selected, depending on library yield and size, using BluePippin (Sage Science, Beverly, MA, USA). Templates were annealed to sequencing primer, bound to polymerase (P6), and then bound to PacBio Mag-Beads and SMRTcell sequenced using C4 chemistry. The C. scindens ATCC 35704 genome was assembled by Canu, version 1.5, with an estimated genome size of 3.6 Mb.

Pathway analysis.

The genome was annotated by both Prokka and the SEED database. For each, two mapping methods were used. The first was mapping to the KEGG database, and the other method used the Python-based tool DuctApe.

Bile acid-induction and RNA isolation from Clostridium scindens ATCC 35704.

Clostridium scindens ATCC 35704 was grown to mid-log phase in PO4-buffered DM (control) or in PO4-buffered DM supplemented with two additions (i.e., one at the time of inoculation and one during mid-log phase) of 50 µM cholate or deoxycholate (bile acids were added from methanolic stock solutions). Cells were quenched with RNAprotect (Qiagen) and stored at −80°C until further processing. Total RNA was recovered from cells following disruption by bead beating in the presence of acid phenol as previously reported (58). In brief, stored cells were dissolved in lysis buffer (200 mM NaCl, 20 mM EDTA, and diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water) and transferred to 2-ml screw-cap bead-beating tubes (Sarstedt AG & Co. KG, Nümbrecht, Germany). Cells were washed with the same buffer and resuspended in 500 µl of lysis buffer. To each tube, 200 μl of zirconium beads, 210 μl of 20% SDS (Ambion, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA), and 1 ml of 5:1 acid phenol were added. Cells were disrupted on a Mini-BeadBeater (Biospec Products, Inc., Bartlesville, OK, USA) at maximum speed twice for 1 min, with tubes kept on ice in between treatments. The aqueous and phenol phases were separated by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 1 min, and the aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube and washed once with 1 ml of 5:1 acid-phenol. Nucleic acids in the aqueous phase were precipitated at −80°C for 60 min by addition of 1/10 volume of 5 M ammonium acetate (Ambion), 1 μl of Glycoblue (Ambion), 1 µl of RNase inhibitor (New England Biolabs [NEB], Ipswich, MA, USA), and 1 volume of ice-cold isopropanol, followed by centrifugation at 13,600 × g for 30 min. Precipitated nucleic acids were treated with RNase-free Turbo DNase (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions to remove contaminated genomic DNA. Total RNA was purified using a MEGAclear kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA purity and integrity were checked spectrophotometrically by the A260/A280 ratio and by separating 16S and 23S rRNA on a 1% agarose gel, respectively.

RNA-Seq analysis.

Stranded RNA-Seq libraries were constructed and sequenced at the DNA Services laboratory of the Roy J. Carver Biotechnology Center at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign using aTruSeq Stranded RNA sample preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Briefly, total RNA was quantitated by Qubit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) and checked for integrity on a 2% eGel (Life Technologies). Starting with 1 μg of RNA, rRNA was removed from the total RNA using a Ribo-Zero Magnetic Bacteria kit (Illumina, CA). First-strand synthesis was performed with a random hexamer and SuperScript II (Life Technologies). Double-stranded DNA was blunt ended, 3′ end A-tailed, and ligated to unique dual-indexed adaptors. The adaptor-ligated double-stranded cDNA was amplified by PCR for 8 cycles with Kapa HiFi polymerase (Kapa Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA). The final libraries were quantitated on Qubit, and the average size was determined on an AATI Fragment Analyzer (Advanced Analytics, Ames, IA, USA). Libraries were pooled evenly, and the pool was cleaned one additional time using a 50/50 ratio with AxyPrep Mag PCR Cleanup beads (Axygen, Inc., Union City, CA, USA) to ensure removal of primer and adaptor dimers and then evaluated on an AATI Fragment Analyzer. The final pool was diluted to a 5 nM concentration and further quantitated by quantitative PCR (qPCR) on a Bio-Rad CFX Connect Real-Time System (Bio-Rad).

The final pool containing 6 libraries was loaded onto one lane of an eight-lane flow cell each for cluster formation on the cBOT and then sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 with SBS (version 1) sequencing reagents from one end of the molecules, for a total read length of 100 nucleotides (nt). The run generates bcl files which are converted into adaptor-trimmed demultiplexed fastq files using bcl2fastq, version 2.20, conversion software (Illumina).

Bioinformatics.

Quality control of raw RNA-Seq reads was performed by using the FastQC, version 0.11.5. Reads that had quality scores of <32 were used for further analysis. Raw reads were aligned with rRNA sequences prepared from the genome of C. scindens ATCC 35704 using bowtie2 (version 2.3.3.1). Unaligned files were saved and realigned with the genome of C. scindens ATCC 35704 using the same tool. Output sam files were converted to the bam format using Samtools (version 0.1.6) and were name sorted prior to input into HTSeq (version 0.9.1). HTSeq counting was performed in union mode against a gene feature format (GFF) annotation of C. scindens ATCC 35704. Reads were counted against coding DNA sequences (CDS) of the organism. Differential gene expression analysis was performed using edgeR (59, 60) and limma (61) R packages. A minimum P value of <0.05 was accepted as indicating differentially expressed genes. Gene expression (Bonferroni corrected) is reported as log2FC with a cutoff of 1.58 (3-fold change) and a false discovery rate (FDR) cutoff of <0.05. Genes were binned according to known functionality, and totals were generated for upregulated and downregulated genes. Category analysis was performed using the eggNOG eggnog-mapper (web interface with bacteria as taxonomic scope and DIAMOND as search program) (62).

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR).

Differential expression of selected genes under control, CA-induced, and DCA-induced conditions was observed using a Light Cycler 480 Real-Time PCR System (Roche Diagnostics, Risch-Rotkreuz, Switzerland). Primers for the C. scindens genes baiE (forward, 5′-CTGGAGACCACTCTGTCACC-3′; reverse, 5′-ATACCATCTGCCCGTAGCC-3′) and urocanate reductase (forward, 5′-AGGGAGATGGAATCTGGGCT-3′; reverse, 5′-TGAAGCAGCATGGTCTGGAG-3′) were amplified in triplicate from four replicates and compared to the housekeeping gene recA (forward, 5′-TGGAAAAGGCACGGTTATGAAAC-3′; reverse 5′-CAACCACACGGATGTTCTTACG-3′). Relative abundance was quantified using the ΔΔCT (where CT is threshold cycle) method, and average log2FC was determined. A t test was performed using triplicate averages to observe significant differences in expression levels between CA- and DCA-induced and control cultures.

Accession number(s)

RNA-Seq and PacBio genome data sets were submitted to NCBI under BioProject number PRJNA508260.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided to J.M.R. for new faculty start-up through the Department of Animal Sciences at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (grant Hatch ILLU-538-916) as well as Illinois Campus Research Board RB18068. This work was also supported by grants (J.M.R) 1RO1 CA204808-01, NIH R01CA179243, and the Young Investigators Grant for Probiotic Research (Danone, Yakult). L.L. is supported by a Graduate Research Fellowship through the National Science Foundation. P.G.W. is supported by an UIC Cancer Education and Career Development Training Program award by the Institute for Health Research and Policy at the University of Illinois at Chicago with funding by the National Cancer Institute (grant no. T32CA057699). We also acknowledge research grants from the Department of Biological Sciences (A.I., J.W., A.A., and E.S.), College of Sciences (J.W., A.A., E.S., and O.P.), Graduate School (R.S. and O.P.), and the Sandra & Jack Pines Honors College (A.A.) at Eastern Illinois University.

We thank Phillip B. Hylemon for careful review of the manuscript. This project used the UW-Milwaukee Great Lakes Genomics Center Pacific Biosciences RSII DNA sequencing and bioinformatics services.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00052-19.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vlahcevic ZR, Heuman DM, Hylemon PB. 1996. Physiology and pathophysiology of enterohepatic circulation of bile acids, p 376–417. In Zakim D, Boyer T (ed), Hepatology: a textbook of liver disease, 3rd ed, vol 1 Saunders, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hofmann AF. 1984. Chemistry and enterohepatic circulation of bile acids. Hepatology 4:4S–14S. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840040803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ridlon JM, Kang DJ, Hylemon PB. 2006. Bile salt biotransformations by human intestinal bacteria. J Lipid Res 47:241–259. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R500013-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ridlon JM, Harris SC, Bhowmik S, Kang D-J, Hylemon PB. 2016. Consequences of bile salt metabolism by intestinal bacteria. Gut Microbes 7:22–39. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2015.1127483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ridlon JM, Alves JM, Hylemon PB, Bajaj JS. 2013. Cirrhosis, bile acids and gut microbiota: unraveling a complex relationship. Gut Microbes 4:382–387. doi: 10.4161/gmic.25723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doerner KC, Takamine F, LaVoie CP, Mallonee DH, Hylemon PB. 1997. Assessment of fecal bacteria with bile acid 7α-dehydroxylating activity for the presence of bai-like genes. Appl Environ Microbiol 63:1185–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White BA, Lipsky RL, Fricke RJ, Hylemon PB. 1980. Bile acid induction specificity of 7α-dehydroxylase activity in an intestinal Eubacterium species. Steroids 35:103–109. doi: 10.1016/0039-128X(80)90115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitahara M, Takamine F, Imamura T, Benno Y. 2000. Assignment of Eubacterium sp. VPI 12708 and related strains with high bile acid 7α-dehydroxylating activity to Clostridium scindens and proposal of Clostridium hylemonae sp. nov., isolated from human faeces. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 5:971–978. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-3-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bokkenheuser VD, Morris GN, Ritchie AE, Holdeman LV, Winter J. 1984. Biosynthesis of androgen from cortisol by a species of Clostridium recovered from human fecal flora. J Infect Dis 149:489–494. doi: 10.1093/infdis/149.4.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winter J, Morris GN, O'Rourke-Locascio S, Bokkenheuser VD, Mosbach EH, Cohen BI, Hylemon PB. 1984. Mode of action of steroid desmolase and reductases synthesized by Clostridium “scindens” (formerly Clostridium strain 19). J Lipid Res 25:1124–1131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris GN, Winter J, Cato EP, Ritchie AE, Bokkenheuser VD. 1985. Clostridium scindens sp. nov., a human intestinal bacterium with desmolytic activity on corticoids. Int J Sys Bacteriol 35:478–481. doi: 10.1099/00207713-35-4-478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergstrom S, Lindstedt S, Samuelsson B. 1959. Bile acids and steroids. LXXXII. On the mechanism of deoxycholic acid formation in the rabbit. J Biol Chem 234:2022–2025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhowmik S, Chiu HP, Jones DH, Chiu HJ, Miller MD, Xu Q, Farr CL, Ridlon JM, Wells JE, Elsliger MA, Wilson IA, Hylemon PB, Lesley SA. 2016. Structure and functional characterization of a bile acid 7α dehydratase BaiE in secondary bile acid synthesis. Proteins Mar 84:316–331. doi: 10.1002/prot.24971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhowmik S, Jones DH, Chiu HP, Park IH, Chiu HJ, Axelrod HL, Farr CL, Tien HJ, Agarwalla S, Lesley SA. 2014. Structural and functional characterization of BaiA, an enzyme involved in secondary bile acid synthesis in human gut microbe. Proteins 82:216–229. doi: 10.1002/prot.24353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doden H, Sallam LA, Devendran S, Ly L, Doden G, Daniel SL, Alves JMP, Ridlon JM. 2018. Metabolism of oxo-bile acids and characterization of recombinant 12α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases from bile acid 7α-dehydroxylating human gut bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e00235-18. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00235-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marion S, Studer N, Desharnais L, Menin L, Escrig S, Meibom A, Hapfelmeier S, Bernier-Latmani R. 27 December 2018. In vitro and in vivo characterization of Clostridium scindens bile acid transformations. Gut Microbes doi: 10.1080/19490976.2018.1549420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamekura M, Oesterhelt D, Wallace R, Anderson P, Kushner DJ. 1988. Lysis of halobacteria in bacto-peptone by bile acids. Appl Environ Microbiol 54:990–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ditscheid B, Keller S, Jahreis G. 2009. Faecal steroid excretion in humans is affected by calcium supplementation and shows gender-specific differences. Eur J Nutr 48:22–30. doi: 10.1007/s00394-008-0755-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamilton JP, Xie G, Raufman JP, Hogan S, Griffin TL, Packard CA, Chatfield DA, Hagey LR, Steinbach JH, Hofmann AF. 2007. Human cecal bile acids: concentration and spectrum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 293:G256–G263. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00027.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allison MJ, Robinson IM, Baetz AL. 1974. Tryptophan biosynthesis from idole-3-acetic acid by anaerobic bacteria from the rumen. J Bacteriol 117:175–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JH, Wood TK, Lee J. 2015. Role of indole as an interspecies and interkingdom signaling molecule. Trends Microbiol 23:707–718. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scherzer R, Gdalevsky GY, Goldgur Y, Cohen-Luria R, Bittner S, Parola AH. 2009. New tryptophanase inhibitors: towards prevention of bacterial biofilm formation. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 24:350–355. doi: 10.1080/14756360802187612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ridlon JM, McGarr SE, Hylemon PB. 2005. Development of methods for the detection and quantification of 7α-dehydroxylating clostridia, Desulfovibrio vulgaris, Methanobrevibacter smithii, and Lactobacillus plantarum in human feces. Clin Chim Acta 357:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris SC, Devendran S, Alves JMP, Mythen SM, Hylemon PB, Ridlon JM. 2018. Identification of a gene encoding a flavoprotein involved in bile acid metabolism by the human gut bacterium Clostridium scindens ATCC 35704. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 1863:276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baron SF, Franklund CV, Hylemon PB. 1991. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the gene coding for bile acid 7α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase from Eubacterium sp. strain VPI 12708. J Bacteriol 173:4558–4569. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.15.4558-4569.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ridlon JM, Hylemon PB. 2012. Identification and characterization of two bile acid coenzyme A transferases from Clostridium scindens, a bile acid 7α-dehydroxylating intestinal bacterium. J Lipid Res 53:66–76. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M020313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo Y, Kalathur RC, Liu Q, Kloss B, Bruni R, Ginter C, Kloppmann E, Rost B, Hendrickson WA. 2015. Protein structure. Structure and activity of tryptophan-rich TSPO proteins. Science 347:551–555. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hylemon PB, Melone PD, Franklund CV, Lund E, Björkhem I. 1991. Mechanism of intestinal 7 α-dehydroxylation of cholic acid: evidence that allo-deoxycholic acid is an inducible side-product. J Lipid Res 32:89–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thanassi DG, Cheng LW, Nikaido H. 1997. Active efflux of bile salts by Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 179:2512–2518. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2512-2518.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo Y, Helmann JD. 2012. Analysis of the role of Bacillus subtilis σ(M) in β-lactam resistance reveals an essential role for c-di-AMP in peptidoglycan homeostasis. Mol Microbiol 83:623–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07953.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thackray PD, Moir A. 2003. SigM, an extracytoplasmic function sigma factor of Bacillus subtilis, is activated in response to cell wall antibiotics, ethanol, heat, acid, and superoxide stress. J Bacteriol 185:3491–3498. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.12.3491-3498.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Urdaneta V, Casadesús J. 2017. Interactions between bacteria and bile salts in the gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary tracts. Front Med (Lausanne) 4:163. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Begley M, Gahan CG, Hill C. 2005. The interaction between bacteria and bile. FEMS Microbiol Rev 29:625–651. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurdi P, van Veen HW, Tanaka H, Mierau I, Konings WN, Tannock GW, Tomita F, Yokota A. 2000. Cholic acid is accumulated spontaneously, driven by membrane ΔpH, in many lactobacilli. J Bacteriol 182:6525–6528. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.22.6525-6528.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watanabe M, Fukiya S, Yokota A. 2017. Comprehensive evaluation of the bactericidal activities of free bile acids in the large intestine of humans and rodents. J Lipid Res 58:1143–1152. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M075143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yasugi M, Okuzaki D, Kuwana R, Takamatsu H, Fujita M, Sarker MR, Miyake M. 2016. Transcriptional profile during deoxycholate-induced sporulation in a Clostridium perfringens isolate causing foodborne illness. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:2929–2942. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00252-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bernstein C, Bernstein H, Payne CM, Beard SE, Schneider J. 1999. Bile salt activation of stress response promoters in Escherichia coli. Curr Microbiol 39:68–72. doi: 10.1007/s002849900420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Breton YL, Mazé A, Hartke A, Lemarinier S, Auffray Y, Rincé A. 2002. Isolation and characterization of bile salts-sensitive mutants of Enterococcus faecalis. Curr Microbiol 45:434–439. doi: 10.1007/s00284-002-3714-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White BA, Cacciapuoti AF, Fricke RJ, Whitehead TR, Mosbach EH, Hylemon PB. 1981. Cofactor requirements for 7 α-dehydroxylation of cholic and chenodeoxycholic acid in cell extracts of the intestinal anaerobic bacterium, Eubacterium species V.P.I. 12708. J Lipid Res 22:891–898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolf PG, Biswas A, Morales SE, Greening C, Gaskins HR. 2016. H2 metabolism is widespread and diverse among human colonic microbes. Gut Microbes 7:235–245. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2016.1182288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mead GC. 1971. The amino acid-fermenting clostridia. J Gen Microbiol 67:47–56. doi: 10.1099/00221287-67-1-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fonknechten N, Chaussonnerie S, Tricot S, Lajus A, Andreesen JR, Perchat N, Pelletier E, Gouyvenoux M, Barbe V, Salanoubat M, Le Paslier D, Weissenbach J, Cohen GN, Kreimeyer A. 2010. Clostridium sticklandii, a specialist in amino acid degradation: revisiting its metabolism through its genome sequence. BMC Genomics 11:555. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ridlon JM, Wolf PG, Gaskins HR. 2016. Taurocholic acid metabolism by gut microbes and colon cancer. Gut Microbes 22:1–15. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2016.1150414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma C, Han M, Heinrich B, Fu Q, Zhang Q, Sandhu M, Agdashian D, Terabe M, Berzofsky JA, Fako V, Ritz T, Longerich T, Theriot CM, McCulloch JA, Roy S, Yuan W, Thovarai V, Sen SK, Ruchirawat M, Korangy F, Wang XW, Trinchieri G, Greten TF, 2018, Gut microbiome-mediated bile acid metabolism regulates liver cancer via NKT cells. Science 360:eaan5931. doi: 10.1126/science.aan5931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshimoto S, Loo TM, Atarashi K, Kanda H, Sato S, Oyadomari S, Iwakura Y, Oshima K, Morita H, Hattori M, Hattori M, Honda K, Ishikawa Y, Hara E, Ohtani N. 2013. Obesity-induced gut microbial metabolite promotes liver cancer through senescence secretome. Nature 499:97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hale VL, Chen J, Johnson S, Harrington SC, Yab TC, Smyrk TC, Nelson H, Boardman LA, Druliner BR, Levin TR, Rex DK, Ahnen DJ, Lance P, Ahlquist DA, Chia N. 2017. Shifts in the fecal microbiota associated with adenomatous polyps. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 26:85–94. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]