Abstract

Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH), especially resulting from placenta accreta spectrum (PAS), has become a worldwide concern in maternity care. We describe a novel method of uterine compression sutures (the ‘Nausicaa’ technique) as an alternative to hysterectomy for patients who have suffered from major PPH. We applied this technique in 68 patients with major PPH during caesarean section (including 43 patients with PAS, 20 patients with placenta praevia totalis, and five patients with uterine atony), and none of these patients required further hysterectomy. We conclude that our Nausicaa suture is a simple and feasible alternative to hysterectomy in patients suffering from major PPH.

Keywords: Placenta accreta spectrum, placenta praevia, postpartum haemorrhage, uterine atony, uterine compression suture, uterus preserving

Introduction

Despite progress in maternal care, postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) remains the leading cause of maternal mortality in both low‐resource and developed countries.1, 2 Placenta accreta, one important cause of major PPH, describes the abnormal adherence or penetration of chorionic villi to the myometrium. Based on the extent of the invasion, placenta accreta further divides into placenta creta, placenta increta, and placenta percreta.3 Now the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) recommends the use of placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) as the terminology to describe the entire pathology.4 Maternal death continues to occur in patients with PAS, even with adequate diagnosis and surgical planning.3, 5, 6 In addition, the incidence of PPH in placenta praevia totalis is 22%, making it far more common in these patients than in uncomplicated pregnancies.7 The question of how to keep patients safe and preserve the uterus during a crisis involving major PPH remains a challenge in modern obstetric practice. In this article, we present our novel ‘Nausicaa’ compression suture as a method for haemostatic control in major PPH (mainly as a result of PAS and placenta praevia). The theory explaining how it controls bleeding and its potential merits are also discussed.

Methods

Patients

Sixty‐eight consecutive patients were enrolled between October 2014 and May 2018. The inclusion criteria were patients suffering from major PPH during caesarean section and refractory to conservative management (e.g., oxytocin and misoprostol administration or uterine massage). The exclusion criterion was a patient with unstable vital signs. In patients with PAS, if we disclosed apparent parametrial invasion, devastating neovascularisation, or overt bladder invasion, either before or during surgery, we preferred to perform a caesarean hysterectomy directly instead of uterine compression sutures. All operations were performed by the same surgeon (JC Shih), with the assistance of other senior obstetricians. Demographic information and operation outcomes were collected along with written consent from the patients.

Surgical procedure

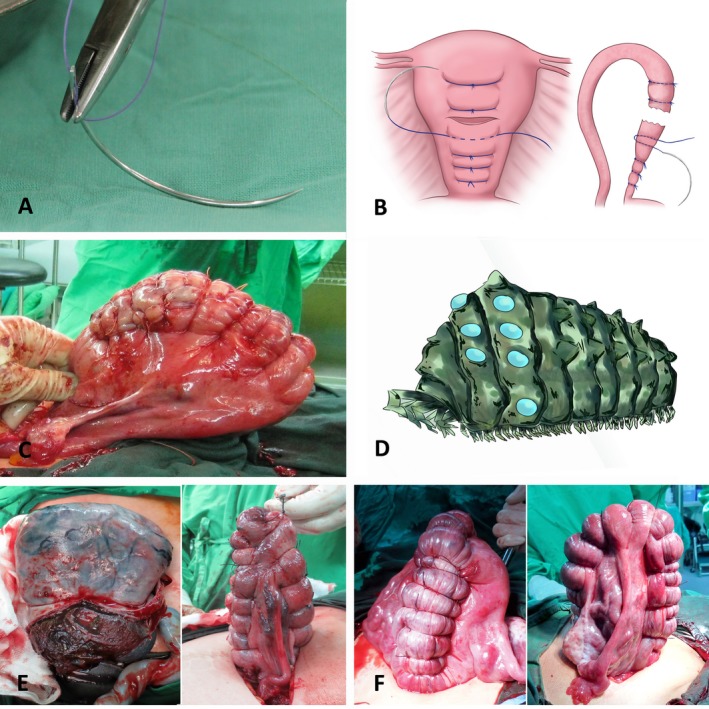

The patients were placed in the lithotomy position so that vaginal bleeding could be checked after compression sutures were applied. After the fetus was delivered, we exteriorised the uterus and inspected the bleeding sites directly while the caesarean wound was still open. In cases with PAS and placenta praevia, excessive bleeding occurred from the implantation site after removal of the placenta. We used a 3/8‐circle curved needle (70 mm in length, with a tapered point; TE70, Mani Inc., Utsunomiya, Japan) threaded with a pre‐cut, 45‐cm‐long, 1‐0 coated Vicryl suture (Polyglactin 910, Sutupak V906E; Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA) for the uterine compression suture (UCS; Figure 1A). This suture material provided a tensile strength that lasted at least 14 days after the initial haemostasis was achieved. We began by needle‐transfixing from the uterine serosa lateral to the bleeding area (or invaded myometrium) inside the uterine cavity. The needle was then threaded along a horizontal course inside the uterine cavity until it encompassed the bleeding area, and then finally emerged at the other side of the uterine serosa. The sutures penetrated the full thickness of the myometrium without stitching the anterior and posterior walls together. Care was taken to avoid transfixing any engorged parametrial vessels. A flat surgical knot was then tied as tightly as possible above the serosa (Figure 1B). Using healthy myometrium as anchoring points for needle transfixion, we did not encounter any tissue destruction by the ligature. To achieve a better compression effect, the assistant often needed to clench the sutured myometrium while the operator tied off the knots (Figure S1A, Video S1). Additional sutures were made approximately 1.5–2.0 cm parallel with the previous stitches until haemostasis was achieved. The final results are shown in a sutured uterus (Figure 1C), in which a pattern resembling the body of the fictitious giant worm ‘Ohm’ (Figure 1D) in the Japanese blockbuster ‘Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind’ can be seen.

Figure 1.

(A) The needle and thread used in this Nausicaa procedure. (B) Schematic illustration of the Nausicaa compression suture (for further details, please refer to the main text). (C) The first case in which we applied a Nausicaa suture. Placenta accreta over the posterior wall was incidentally found during a caesarean section. Adequate haemostasis was successfully accomplished after the Nausicaa suture was applied. (D) The uterus sutured by this technique had the appearance of the giant, shelled worm that appears in the Japanese blockbuster film ‘Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind’ (illustrated here by our professional artist, based on the film and the procedure). (E) A patient (case 3) underwent cervical cerclage at 18 weeks of gestation as a result of repeated spontaneous abortions in the second trimester. Uterine hypoplasia and extensive placenta increta were found during a caesarean section performed for breech presentation of the fetus and preterm premature rupture of membranes at 31 weeks of gestation. We then performed the Nausicaa technique to stop the bleeding and to avoid further hysterectomy. (F) A patient (case 33) who suffered from uterine atony was rescued by the Nausicaa technique applied to both anterior and posterior walls, separately.

Generally, the vesico‐uterine fold needed to be dissected to expose the serosa of the lower uterine segment. In patients with extensive PAS or uterine atony refractory to medical treatment, the Nausicaa UCS was applied separately in both the anterior and posterior walls if needed (Figure 1E,F). The Nausicaa UCS can also be applied in placenta percreta as long as there is no parametrial invasion (Figure 2A–C; Video S2). If no more bleeding is observed, the caesarean incision was closed using a 1‐0 Vicryl continuous suture. A successful procedure was defined as one that required only the UCS technique to achieve adequate haemostasis. Cases involving the prophylactic use of uterine artery embolisation (UAE) or the adjunct use of fibrin glue (Figure S1B) after adequate haemostasis by Nausicaa technique were also included in the successful group. In this cohort, as there was no myometrial specimens in most of the patients, we preferred to define PAS according to its clinical–surgical characteristics. We diagnosed placenta creta if we found cotyledons abnormally attaching to the myometrium, and the lack of a smooth decidual layer in the removed placental fragments. We defined placenta increta if there were several discernable placenta fragments embedded inside the myometrium after attempting to remove all pieces of the placenta. Placenta percreta indicated that the invasive placenta had already breached the uterine serosa or urinary bladder. All of these findings can be inspected directly during the operation.

Figure 2.

(A) A woman (gravida 5, para 4; case 50) presented with placenta praevia percreta at 37 weeks of gestation. A presurgical diagnosis was made using high‐resolution ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging. (B) After temporary aortic occlusion was performed with a balloon catheter, we attempted to manually remove the placenta from the hysterotomy, but the procedure resulted in uterine rupture at the site of the placenta percreta. (C) Haemostasis was achieved by the Nausicaa technique, which was supplemented by the application of fibrin gel inside the uterine cavity (for further details, please refer to Video S2). (D) A patient presented with placenta praevia increta and extensive pelvic adhesion at 35 weeks of gestation (case 41). She had a history of previous myomectomy. In this patient, the Nausicaa suture alone did not achieve complete haemostasis, but gained some time to transfer this patient for salvage UAE. (E) In most cases, a normal uterine contour is observed on hysteroscopy at 3 months after the Nausicaa suture procedure. (F) In some patients, degenerated placenta fragments are found during a hysteroscopy examination.

Follow‐up

Vital signs, lochia, and wound drainage were closely monitored in all patients during hospitalisation. The patients were scheduled for a follow‐up visit 6 weeks after discharge. In the postpartum clinic, a pelvic ultrasound was arranged to identify any pelvic abnormalities. A hysteroscopy examination of the uterine cavity was suggested for 3 months later to identify any intrauterine adhesion.

Results

In this series, the causes of PPH were placenta praevia totalis with PAS [n = 36, including 26 cases of placenta creta, seven cases of placenta increta (Figure S1C,D), and three cases of placenta percreta], PAS over the posterior or fundal wall (n = 7) (Figure S1E,F), placenta praevia totalis without PAS (n = 20), and uterine atony (n = 5). On average, 8.5 minutes (range: 5–22 minutes) were required to complete this procedure. None of the patients required further hysterectomy. The success rate of the Nausicaa sutures for achieving adequate haemostasis was 97.0%. The technique, when used alone, failed to achieve effective haemostasis in two patients with extensive placenta increta (Figure 2D). Both patients were sent for UAE twice because of uncontrollable bleeding (3000 and 1600 ml of blood lost during the operation, respectively). Adequate haemostasis was achieved for another five patients, but they were sent for prophylactic UAE to ensure safe recovery after the operation. In five patients with advanced PAS, we also used temporary balloon occlusion at the abdominal aorta during surgery as an adjunctive measure to control bleeding, and the balloon was deflated when haemostasis was complete.

Table S1 summarises the demographic data and clinical outcomes. There were no cases of maternal mortality or severe morbidities related to the disease itself or to the procedure. Blood loss ranged from 500 to 4100 ml (mean, 1244 ml), and 26 of these patients required a perioperative blood transfusion. Eight patients were admitted to the intensive care unit for observation of vital signs and advanced respiratory care. Except for two patients who failed to stop bleeding, none of the patients developed delayed haemorrhage or disseminated intravascular coagulation that required further management. Postoperative recovery was generally uneventful. Notably, two patients developed a fever and formed an intra‐abdominal abscess resulting from partial uterine necrosis on days 4 and 10 after surgery, respectively. We subsequently performed an open debridement for the first patient and computed tomography (CT)‐guided pigtail drainage for the second patient. Both patients had an uncomplicated recovery. The majority of the included patients were discharged on postpartum day 5, similar to other routine patients, except for one who stayed for 12 days as a result of postoperative ileus. All of the patients had a normal volume of lochia after discharge from the hospital. Ultrasound was performed at the postpartum clinic and revealed no apparent retention of placenta or haematometra. Only 13 of the patients were willing to undergo a hysteroscopy examination: ten of these patients were found to have a smooth uterine contour (Figure 2E); two patients had an intrauterine adhesion over the sutured site; and we failed to examine one patient failed because of cervical stenosis. Degenerated placental elements were identified in five of these patients (Figure 2F), but no further treatment was advised for any of them. Three patients conceived spontaneously and underwent a repeated caesarean section that showed no signs of apparent intraperitoneal adhesion.

Discussion

Currently, a number of UCS methods are proposed for treating PPH,8, 9, 10, 11, 12 but no systematic classification of these therapies is universally accepted.13, 14 As suggested by previous authors, to be a good adjunct for haemostasis, the UCS should fulfil three essential prerequisites: it should be easy to perform, effective, and safe.14 The most well‐known UCS methods are probably the B‐Lynch brace suture, which was devised by B‐Lynch et al., and the square suture, which was introduced by Cho et al.15, 16 Technically, these approaches are very different. The former requires the caesarean incision to be open during suturing, and involves the use of long‐length threading with a large area of compression. In contrast, Cho's suture has the opposite characteristics to those described above. These UCSs generally provide the satisfactory control of bleeding, although some patients have developed rare complications, such as partial uterine necrosis and intrauterine synechia.17, 18, 19

According to Hayman et al.,20 the limitations of the B‐Lynch brace suture include the need to undergo hysterotomy and the fact that it is difficult to recall all of the sophisticated steps of this procedure during an emergency. We reasoned, however, that hysterotomy may allow for a direct inspection to determine whether haemostasis was accomplished. In addition, because the thread used in B‐Lynch suture traverses such a long distance, it may sometimes encounter suture tension, it may not be strong enough to halt all of the uterine flow, or the thread might break while being tied off. In terms of the compression effect, the compression area provide by each single Cho's square suture only encompasses a small region, and thus the haemostatic effect is probably better achieved in a focal region. Nevertheless, the needle must penetrate through both the anterior and posterior walls. In patients with hypertrophic myometrium (such as adenomyosis), it may be difficult to simultaneously guide the needle through both the anterior and posterior walls. Additionally, because the anterior and posterior walls are stitched together, uterine synechiae may theoretically occur because lochia and debris are contained within the compressed area.

Our Nausicaa suture has some potential merits. First, the procedure is relatively simple to perform and to recall. Second, the compression sutures are tied off while leaving the caesarean incision open. The failure rate of this suture might be lower because it allows haemostasis to be directly confirmed. In addition, the thread traverses a short distance (approximately 5–10 cm in length) that is probably shorter than that required by any existing UCS. Given the fixed tension that the thread can bear, this type of UCS may provide greater direct tension to the compressed tissue. Finally, the suture does not stitch the anterior and posterior walls together. The lochia and necrotic debris can therefore drain out without the potential formation of pyometra. Despite that, the Nausicaa procedure has certain weaknesses. We cannot apply this technique if the uterine serosa (overlying the invaded myometrium) cannot be dissected as a result of extensive peritoneal adhesion.

Generally, in verified cases of placenta accreta, planned placenta removal during surgery should be avoided;6 however, this concept has been challenged by some experts.21 In line with these opinions, in these patients (43 patients of PAS), we remove the placenta manually and then apply Nausicaa compression sutures. Despite the risk of immediate bleeding, removing the placenta decreases the risk of delayed haemorrhage and sepsis. Although hysterectomy with placenta left in situ is considered the standard treatment for PAS by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines,6 it might not be appropriate in women with a strong desire for future fertility. Palacios‐Jaraquemada et al.22 have advocated a technique involving a ‘one‐step’ surgery, in which the invaded myometrium is excised and the uterus preserved. This technique may be too sophisticated for general obstetricians, however.

Conclusion

The ‘Nausicaa’ technique is simple to perform and provides an effective alternative to hysterectomy in the case of PPH. It is particularly helpful for preserving fertility and avoiding extensive surgery in cases of PAS without parametrial invasion. Further studies should be conducted to review the fertility outcomes and potential complications that might be encountered with this procedure.

Disclosure of interests

None declared. Completed disclosure of interests form available to view online as supporting information.

Contribution to authorship

J‐CS designed the surgical technique and wrote this article. J‐CS, JK, and M‐WL were the principal surgeons who performed or participated in these operations. K‐LL was responsible for the UAE. J‐HY was in charge of hysteroscopy examinations. C‐UY made the illustration of Figure 1B. All authors approved the final version of the article.

Details of ethics approval

At our institution, studies involving the modification of an existing surgical technique are exempted from formal Institutional Review Board approval. Before every procedure, written informed consent was obtained from each patient after the patients were informed of the potential benefits and risks.

Funding

This work was supported by research grants from the National Taiwan University Hospital (106‐17) and the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (106‐2314‐B‐002‐201).

Supporting information

Figure S1. (A) For a better compression effect, the assistant often needed to clench the sutured myometrium while the operator tied off the knots. (B) Applying fibrin glue for minor bleeding from uterine serosa. (C) In this patient of placenta praevia increta (case 43), engorged vessels were seen on the uterine serosa. (D) We removed the placenta and preserved the uterus in this patient (case 43) using the Nausicaa technique. (E) A patient (case 55) presented with placenta increta over the fundal wall and uterine rupture (probably as a result of a previous myomectomy) at 32 weeks of gestation. (F) We applied the Nausicaa suture for her (case 55) to stop the bleeding and preserved her fertility.

Table S1. Demography and clinical outcomes for the 68 patients in this series.

Video S1. The assistant clenched the flaccid uterus while the operator tied off the knots in this patient suffering from uterine atony.

Video S2. Step‐by‐step explanation of the uterine‐preserving technique for placenta praevia percreta using the Nausicaa procedure.■

Acknowledgement

We thank Ms. Tiffany Shih for the delicate art drawing for Figure 1D.

Shih J‐C, Liu K‐L, Kang J, Yang J‐H, Lin M‐W, Yu C‐U. ‘Nausicaa’ compression suture: a simple and effective alternative to hysterectomy in placenta accreta spectrum and other causes of severe postpartum haemorrhage. BJOG 2019; 126:412–417.

Linked article This article is commented on by S Matsubara, p. 418 in this issue. To view this article visit https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.15422.

References

- 1. WHO Recommendations for the Prevention and Treatment of Postpartum Haemorrhage. Geneva: WHO; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, Gulmezoglu AM, Van Look PF. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet 2006;367:1066–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jauniaux E, Collins S, Burton GJ. Placenta accreta spectrum: pathophysiology and evidence‐based anatomy for prenatal ultrasound imaging. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;218:75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jauniaux E, Silver RM, Matsubara S. The new world of placenta accreta spectrum disorders. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2018;140:259–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Committee on Obstetric Practice . Committee opinion no. 529: placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:207–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Khong TY. The pathology of placenta accreta, a worldwide epidemic. J Clin Pathol 2008;61:1243–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fan D, Xia Q, Liu L, Wu S, Tian G, Wang W, et al. The incidence of postpartum haemorrhage in pregnant women with placenta previa: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS One 2017;12:e0170194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang ZW, Liu CY, Yu N, Guo W. Removable uterine compression sutures for postpartum haemorrhage. BJOG 2015;122:429–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li GT, Li XF, Liu YJ, Li W, Xu HM. Symbol “&” suture to control atonic postpartum haemorrhage with placenta previa accreta. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2015;291:305–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Matsubara S, Kuwata T, Baba Y, Usui R, Suzuki H, Takahashi H, et al. A novel “uterine sandwich’ for haemorrhage at caesarean section for placenta praevia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2014;54:283–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matsubara S, Yano H, Ohkuchi A, Kuwata T, Usui R, Suzuki M. Uterine compression sutures for postpartum haemorrhage: an overview. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2013;92:378–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ghezzi F, Cromi A, Uccella S, Raio L, Bolis P, Surbek D. The Hayman technique: a simple method to treat postpartum haemorrhage. BJOG 2007;114:362–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Matsubara S, Takahashi H, Ohkuchi A. Need for systematic classification of various uterine compression sutures. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2015;41:1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li GT, Li XF, Wu BP, Li GR, Xu HM. Three cornerstones of uterine compression sutures: simplicity, safety and efficacy. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2015;292:949–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cho JH, Jun HS, Lee CN. Hemostatic suturing technique for uterine bleeding during cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2000;96:129–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. B‐Lynch C, Coker A, Lawal AH, Abu J, Cowen MJ. The B‐Lynch surgical technique for the control of massive postpartum haemorrhage: an alternative to hysterectomy? Five cases reported. BJOG 1997;104:372–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Poujade O, Grossetti A, Mougel L, Ceccaldi PF, Ducarme G, Luton D. Risk of synechiae following uterine compression sutures in the management of major postpartum haemorrhage. BJOG 2011;118:433–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reyftmann L, Nguyen A, Ristic V, Rouleau C, Mazet N, Dechaud H. Partial uterine wall necrosis following Cho hemostatic sutures for the treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. Gynecol Obstet Fertil 2009;37:579–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gottlieb AG, Pandipati S, Davis KM, Gibbs RS. Uterine necrosis – a complication of uterine compression sutures. Obstet Gynecol 2008;112:429–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hayman RG, Arulkumaran S, Steer PJ. Uterine compression sutures: surgical management of postpartum haemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:502–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Matsubara S, Takahashi H. Intentional placental removal on suspicious placenta accreta spectrum: still prohibited? Arch Gynecol Obstet 2018;297:1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Palacios Jaraquemada JM, Pesaresi M, Nassif JC, Hermosid S. Anterior placenta percreta: surgical approach, hemostasis and uterine repair. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2004;83:738–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. (A) For a better compression effect, the assistant often needed to clench the sutured myometrium while the operator tied off the knots. (B) Applying fibrin glue for minor bleeding from uterine serosa. (C) In this patient of placenta praevia increta (case 43), engorged vessels were seen on the uterine serosa. (D) We removed the placenta and preserved the uterus in this patient (case 43) using the Nausicaa technique. (E) A patient (case 55) presented with placenta increta over the fundal wall and uterine rupture (probably as a result of a previous myomectomy) at 32 weeks of gestation. (F) We applied the Nausicaa suture for her (case 55) to stop the bleeding and preserved her fertility.

Table S1. Demography and clinical outcomes for the 68 patients in this series.

Video S1. The assistant clenched the flaccid uterus while the operator tied off the knots in this patient suffering from uterine atony.

Video S2. Step‐by‐step explanation of the uterine‐preserving technique for placenta praevia percreta using the Nausicaa procedure.■