Abstract

Once‐daily deferasirox dispersible tablets (DT) have a well‐defined safety and efficacy profile and, compared with parenteral deferoxamine, provide greater patient adherence, satisfaction, and quality of life. However, barriers still exist to optimal adherence, including gastrointestinal tolerability and palatability, leading to development of a new film‐coated tablet (FCT) formulation that can be swallowed with a light meal, without the need to disperse into a suspension prior to consumption. The randomized, open‐label, phase II ECLIPSE study evaluated the safety of deferasirox DT and FCT formulations over 24 weeks in chelation‐naïve or pre‐treated patients aged ≥10 years, with transfusion‐dependent thalassemia or IPSS‐R very‐low‐, low‐, or intermediate‐risk myelodysplastic syndromes. One hundred seventy‐three patients were randomized 1:1 to DT (n = 86) or FCT (n = 87). Adverse events (overall), consistent with the known deferasirox safety profile, were reported in similar proportions of patients for each formulation (DT 89.5%; FCT 89.7%), with a lower frequency of severe events observed in patients receiving FCT (19.5% vs. 25.6% DT). Laboratory parameters (serum creatinine, creatinine clearance, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase and urine protein/creatinine ratio) generally remained stable throughout the study. Patient‐reported outcomes showed greater adherence and satisfaction, better palatability and fewer concerns with FCT than DT. Treatment compliance by pill count was higher with FCT (92.9%) than with DT (85.3%). This analysis suggests deferasirox FCT offers an improved formulation with enhanced patient satisfaction, which may improve adherence, thereby reducing frequency and severity of iron overload‐related complications.

1. Introduction

Transfusion and iron chelation therapy can be a lifelong requirement for many patients with transfusion‐dependent anemias. Compliance with iron chelation therapy can influence the frequency and severity of iron overload‐related complications,1 with demonstrated improvement in organ dysfunction and survival in patients compliant with iron chelation therapy.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 The once‐daily oral deferasirox dispersible tablet (DT) formulation (Exjade®), available since 2005, offered an improved option over parenteral deferoxamine (Desferal®), providing greater compliance, patient satisfaction, and health‐related quality of life.7, 8 The efficacy and safety of deferasirox DT has been well‐defined through an extensive clinical trial program in adult and pediatric patients with a variety of anemias, including thalassemia, myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), sickle‐cell disease, and other rare anemias,9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and has been used in clinical practice worldwide for over a decade. Nonetheless, barriers to optimal patient acceptance of treatment still exist with deferasirox DT, including palatability, the need to take the drug in a fasting state (ie, not being able to take with food), and drug‐related side effects, notably gastrointestinal (GI) tolerability.14 An improved film‐coated tablet (FCT) formulation of deferasirox (US, Jadenu®; EU, Exjade®) has therefore been developed for oral administration.

Both deferasirox FCT and DT are once‐daily, oral iron chelators that are dosed based on body weight. The FCT contains the same active substance, dose‐adjusted to achieve comparable exposure to that achieved with the DT,15 but excipients (lactose and sodium lauryl sulfate) have been removed. As a result of increased bioavailability of the FCT, doses required to achieve the same chelation effect are ∼30% lower than the DT.15 Deferasirox DT is taken according to labeling recommendations on an empty stomach, at least 30 min before the next meal, and administration requires careful dispersion of the tablets in a glass of water, orange juice, or apple juice, and has a chalky consistency. Deferasirox FCT can be taken orally on an empty stomach or with a light meal (<7% fat content and ∼250 calories), offering a simpler and more convenient mode of administration, and potentially improved GI tolerability (due to a change in excipients and administration with food).

The phase II, randomized, open‐label ECLIPSE study primarily evaluated the overall safety profile, as well as pharmacokinetics (PK), and patient‐reported outcomes (PROs) of deferasirox FCT and DT formulations in patients aged ≥10 years with transfusion‐dependent thalassemia (TDT) or very‐low‐, low‐, or intermediate‐risk MDS, requiring iron chelation therapy.

2. Methods

2.1. Key inclusion/exclusion criteria

Male and female patients aged ≥10 years with TDT or revised International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS‐R) very‐low‐, low‐, or intermediate‐risk MDS were enrolled; patients could have been previously treated with iron chelators and required treatment with deferasirox DT doses ≥30 mg/kg/day (TDT) or ≥20 mg/kg/day (MDS) or be chelation‐naïve. Patients were also required to have a transfusion history of ≥20 packed red blood cell units, anticipated transfusion requirements of ≥8 units/year during the study, and serum ferritin >1000 ng/mL at screening. Key exclusion criteria were: creatinine clearance (CrCl) below contraindication limit as per local label (<60 mL/min or <40 mL/min); serum creatinine (SCr) >1.5 × upper limit of normal (ULN); alanine aminotransferase (ALT) >5 × ULN (unless liver iron concentration confirmed as >10 mg Fe/g dry weight ≤6 months prior to screening); urine protein/creatinine ratio (UPCR) >0.5 mg/mg; or impaired GI function.

2.2. Study design

ECLIPSE was an open‐label, randomized, multicenter, two‐arm, phase II study with the primary endpoint after 24 weeks of treatment (Supporting Information Figure S1). Randomization was stratified by underlying disease and previous chelation treatment. In all chelation‐naïve patients, the starting deferasirox dose was 20 mg/kg/day with DT or 14 mg/kg/day with FCT. For previously treated patients, a washout period of 5 days was required before randomization; all pre‐treated patients well managed on treatment with deferasirox DT, deferoxamine or deferiprone were requested to start on a DT or FCT dose equivalent to their pre‐washout dose (eg, 20 mg/kg/day DT equivalent to 14 mg/kg/day FCT equivalent to ∼75 mg/kg/day deferiprone equivalent to ∼40 mg/kg/day deferoxamine). Deferasirox DT was taken on an empty stomach, at least 30 min before the next meal; FCT was taken (no later than 12:00 pm) with or after a light meal. Dose adjustments to improve treatment response based on serum ferritin levels and investigator's judgment were recommended every 4 weeks for chelation‐naïve patients and every 3 months for pre‐treated patients, in increments of 5‐10 mg/kg/day for DT or 3.5‐7 mg/kg/day for FCT, up to a maximum dose of 40 mg/kg/day for DT and 28 mg/kg/day for FCT. Dose adjustments based on safety and dose reductions for patients unable to tolerate the protocol‐specified dosing schedule were allowed at any time during the study.

The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by independent ethics committees at participating sites. Patients (or parents/guardians) provided written, informed consent prior to enrollment.

2.3. Outcomes

The primary endpoint was overall safety of deferasirox FCT and deferasirox DT formulations, measured by frequency and severity of adverse events (AEs) and changes in laboratory values from baseline to 24 weeks. Secondary endpoints included the evaluation of both formulations on selected GI AEs (diarrhea, constipation, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain) during treatment, estimation of treatment compliance, evaluation of both formulations on patient satisfaction, palatability, and GI symptoms using PROs and evaluation of the PK of both formulations.

Safety was evaluated by monitoring and assessing AEs, changes in laboratory parameters, and clinical observations from the start of study treatment to 30 days after the last intake of study drug. Compliance to treatment was evaluated by relative consumed tablet count (total consumed tablet count/total prescribed tablet count) and patient‐reported treatment compliance using a daily compliance questionnaire. Patient satisfaction, palatability of medicine, and GI symptoms were measured for both formulations using PRO questionnaires (modified Satisfaction with Iron Chelation Therapy [SICT] and palatability questionnaire) and a GI symptoms diary. All PRO instruments used in this study (palatability, GI symptom and modified SICT questionnaires) and estimation of compliance (pill count) followed FDA Guidance to Industry for development. Comprehensive qualitative, linguistic and psychometric validation was performed within this trial; manuscripts on the qualitative validation and psychometric evaluation are in development. The modified SICT questionnaire used 5‐point response scales to assess adherence (six questions), satisfaction/preference (two questions), and concern domains (three questions); higher scores in adherence and satisfaction/preference domains indicated worse adherence, higher scores in concern domain indicated fewer concerns. The palatability questionnaire consisted of four items: taste and aftertaste of the medication (5‐point response scale: 1 = very good; 5 = very bad), whether the medication was taken (ie, whether the patient vomited after swallowing medication or not) and how the patient perceived the amount of medication to be taken (not enough, just enough, or too much). The GI symptom diary consisted of six items: five items (pain in your belly, nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea) rated on an 11‐point scale (0 = best, 10 = worst) and the sixth item, bowel movement frequency during the past 24 h, using seven response options (0 = 0 [none], 1 = 1, 2 = 2, 3 = 3, 4 = 4, 5 = 5‐10, and 6 = ≥11). The modified SICT and palatability questionnaires were completed at weeks 2 (considered as baseline), 3, 13, and end of treatment (within 7 days of the last dose). GI tolerability and treatment compliance diaries were completed daily. Serum ferritin was measured at screening visits 1 and 2, and every 4 weeks starting from week 5 until end of treatment.

Serial blood samples (pre‐dose, 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, and 24 h post‐dose) were collected for a subset of patients to assess deferasirox PK during treatment on the first day of week 1 and week 3; pre‐dose and 2‐h post‐dose on the first day of week 13 and week 21. For all other patients, pre‐dose and 2‐h post‐dose samples were obtained on the first day of week 3, week 13, and week 21.

2.4. Statistical evaluations

Standard descriptive analyses were performed for both formulation groups. No hypothesis was tested. The incidence of any AEs overall and by severity was summarized by treatment using frequency counts, percentages of patients, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for percentages obtained using Clopper–Pearson method. Laboratory data were summarized using absolute change from baseline by treatment arm at each post‐baseline time window. The safety analysis set included all patients who received at least one dose of the study drug and was used for all safety evaluations. The PK analysis set consisted of all patients who received at least one dose of study medication and had at least one evaluable concentration measurement and was used for all PK analyses. Serum ferritin data were considered as an exploratory, non‐safety outcome; absolute and relative change from baseline were summarized by treatment arm at each post‐baseline visit.

3. Results

In total, 173 patients were randomized 1:1 to DT (n = 86) or FCT (n = 87; Table 1). Most patients had TDT (n = 70 in each arm) and 16 patients in each arm had MDS; most had received previous iron chelation therapy (DT, n = 77 [89.5%]; FCT, n = 79 [90.8%]) and had received deferasirox DT prior to the study (DT, n = 68 [79.1%]; FCT, n = 71 [81.6%]; Table 1). Overall, 150 patients (86.7%) completed 24 weeks of treatment; patients discontinued treatment because of AEs (n = 10), protocol deviation (n = 5), withdrawal of consent (n = 3), patient guardian decision (n = 2), and other reasons (administrative problems, death, and physician's decision, n = 1 each).

Table 1.

Patient demographics, disease, and baseline characteristics by treatment

| Variable | Deferasirox DT, N = 86 | Deferasirox FCT, N = 87 | Total, N = 173 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease, n (%) | |||

| Transfusion‐dependent thalassemia | 70 (81.4) | 70 (80.5) | 140 (80.9) |

| MDS | 16 (18.6) | 16 (18.4) | 32 (18.5) |

| Very‐low‐risk MDS | 1 (1.2) | 5 (5.7) | 6 (3.5) |

| Low‐risk MDS | 8 (9.3) | 10 (11.5) | 18 (10.4) |

| Intermediate‐risk MDS | 7 (8.1) | 1 (1.1) | 8 (4.6) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) |

| Mean age ± SD, years | 35.1 ± 18.60 | 34.6 ± 19.97 | 34.9 ± 19.25 |

| Median age (range), years | 29.0 (11‐81) | 27.0 (12‐81) | 28.0 (11‐81) |

| Male:female, n | 39:47 | 46:41 | 85:88 |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 61 (70.9) | 62 (71.3) | 123 (71.1) |

| Asian | 20 (23.3) | 16 (18.4) | 36 (20.8) |

| Other | 5 (5.8) | 9 (10.3) | 14 (8.1) |

| Mean time since diagnosis ± SD, years | 22.3 ± 11.95 | 19.9 ± 11.30 | 21.1 ± 11.66 |

| Previous chelation, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 77 (89.5) | 79 (90.8) | 156 (90.2) |

| No | 9 (10.5) | 8 (9.2) | 17 (9.8) |

| Deferasirox prior to study, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 68 (79.1) | 71 (81.6) | 139 (80.3) |

| No | 18 (20.9) | 16 (18.4) | 34 (19.7) |

| Last chelation therapy received, n (%) | |||

| Deferasirox | 57 (66.3) | 60 (69.0) | 117 (67.6) |

| Deferoxamine | 7 (8.1) | 6 (6.9) | 13 (7.5) |

| Deferiprone | 4 (4.7) | 4 (4.6) | 8 (4.6) |

| Combination therapy | 9 (10.5) | 9 (10.3) | 18 (10.4) |

| Missing | 9 (10.5) | 8 (9.2) | 17 (9.8) |

| Median serum ferritin (range), ng/mL | 2485 (915‐8250) | 2983 (939‐8250) | ‐ |

SD, standard deviation.

3.1. Exposure to treatment and compliance

The mean actual deferasirox DT dose ± SD received during the 24‐week study was 27.5 ± 7.73 mg/kg/day over a mean duration of 154.5 ± 44.67 days (median 168.0 days); the mean actual deferasirox FCT dose ± SD received was 20.8 ± 5.44 mg/kg/day over a mean duration of 163.2 ± 27.76 days (median 169.0 days; Table 2). More patients receiving FCT were in the longest exposure category (≥12 weeks; DT 89.5%; FCT 96.6%) and highest mean actual dose category (≥35 mg/kg/day DT/≥24.5 mg/kg/day FCT; DT n = 16, 18.6%; FCT n = 27, 31.0%; Table 2). However, post‐hoc analyses identified that 23 patients on FCT (26%) were started on a dose that was higher than recommended in the protocol compared with eight patients (9.3%) on DT (not recognized or reported by the investigators as dosing error). Over 24 weeks, dose was interrupted at least once in 43 patients (50.0%) receiving DT and 42 patients (48.3%) receiving FCT, primarily because of dosing error (DT, n = 17; FCT, n = 20) as recorded by investigators in the dosing administration record. Dose adjustments or interruptions because of AEs were performed in 40 patients (46.5%) on DT and 32 patients (36.8%) on FCT; the principal causes were UPCR increased (DT, n = 8 [9.3%]; FCT, n = 10 [11.5%]) and diarrhea (DT, n = 5 [5.8%]; FCT, n = 6 [6.9%]). Other GI AEs of interest leading to dose adjustments in patients on DT or FCT, respectively, were abdominal pain (n = 4 and n = 5), nausea (n = 3 in each arm), constipation (n = 1 and n = 2), and vomiting (n = 2 in each arm). More dose adjustments/interruptions were performed because of severe AEs in patients on DT (n = 12 [14.0%]) than FCT (n = 5 [5.7%]), most frequently diarrhea (DT, n = 2 [2.3%]; FCT, n = 1 [1.1%]) and proteinuria (DT, n = 1 [1.2%]; FCT, n = 1 [1.1%]). Compliance with medication as assessed by relative consumed tablet count was high: 85.3% (95% CI: 81.1, 89.5) in the DT arm and 92.9% (95% CI: 88.8, 97.0) in the FCT arm.

Table 2.

Exposure to study drug by treatment

| Exposure variable | Deferasirox DT, N = 86 | Deferasirox FCT, N = 87 |

|---|---|---|

| Mean exposure ± SD, days | 154.5 ± 44.67 | 163.2 ± 27.76 |

| Median exposure (range), days | 168.0 (2‐224) | 169.0 (30‐239) |

| Exposure category (weeks), n (%) | ||

| <4 | 5 (5.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| ≥4 to <12 | 4 (4.7) | 3 (3.4) |

| ≥12 | 77 (89.5) | 84 (96.6) |

| Mean actual dose ± SD, mg/kg/day | 27.5 (7.73) | 20.8 (5.44) |

| Mean actual dose category, mg/kg/day | 5 (5.8) | 2 (2.3) |

| <15 DT/<10.5 FCT | 28 (32.6) | 26 (29.9) |

| ≥15 to <25 DT/≥10.5 to <17.5 FCT | 37 (43.0) | 32 (36.8) |

| ≥25 to <35 DT/≥17.5 to <24.5 FCT | 16 (18.6) | 27 (31.0) |

| ≥35 DT/≥24.5 FCT |

3.2. Safety of deferasirox DT and FCT

3.2.1. Adverse events

Investigator‐reported AEs regardless of relationship to deferasirox were reported in 77 patients (89.5%) on DT and 78 patients (89.7%) on FCT (Table 3). The most frequently reported AEs were diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain (Table 3). Similar proportions of patients experienced one or more GI AE (defined as abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, nausea, or vomiting): 61.6% of patients (n = 53; 95% CI 50.5, 71.9) receiving deferasirox DT and 58.6% (n = 51; 95% CI 47.6, 69.1) of those receiving FCT, with similar proportions in each treatment arm experiencing diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain; 12.8% and 4.6% of patients in the deferasirox DT and FCT groups, respectively, experienced severe GI AEs (Table 3). Among patients with prior deferasirox treatment, 41 (60.3%) receiving DT and 38 (53.5%) receiving FCT had one or more GI AE; in patients without prior deferasirox treatment, 12 (66.7%) receiving DT and 13 (81.3%) receiving FCT had one or more GI AE. Overall, the exposure‐adjusted incidence of GI AEs was 137 per 100 patient years in the FCT group and 153 per 100 patient years in the DT group. GI hemorrhage and ulcers were seen in 3.5% of patients receiving DT (hematochezia n = 1 and rectal hemorrhage n = 2; Supporting Information); none were observed in patients receiving FCT.

Table 3.

Most common AEs (overall and severe; >10% in any group) regardless of study drug relationship by preferred term and treatment

| Deferasirox DT, N = 86 | Deferasirox FCT, N = 87 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AE | All AEs n (%) | Severe AEs n (%) | All AEs n (%) | Severe AEs n (%) |

| Total | 77 (89.5) | 22 (25.6) | 78 (89.7) | 17 (19.5) |

| Diarrhea | 30 (34.9) | 6 (7.0) | 29 (33.3) | 1 (1.1) |

| Nausea | 23 (26.7) | 2 (2.3) | 24 (27.6) | 1 (1.1) |

| Abdominal pain | 23 (26.7) | 4 (4.7) | 23 (26.4) | 2 (2.3) |

| Increased UPCR (>0.5) | 11 (12.8) | 2 (2.3) | 18 (20.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Vomiting | 19 (22.1) | 1 (1.2) | 15 (17.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Abdominal pain upper | 6 (7.0) | 1 (1.2) | 10 (11.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Constipation | 13 (15.1) | 2 (2.3) | 7 (8.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Headache | 12 (14.0) | 2 (2.3) | 5 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) |

AEs with a difference of ≥5% between treatment arms were increased UPCR (DT, 12.8% [n = 11]; FCT, 20.7% [n = 18]), hematuria (DT, 2.3% [n = 2]; FCT 9.2% [n = 8]), constipation (DT, 15.1% [n = 13]; FCT, 8.0% [n = 7]), headache (DT, 14.0% [n = 12]; FCT, 5.7% [n = 5]), and influenza (DT, 5.8% [n = 5]; FCT, 0.0% [n = 0]). A post‐hoc evaluation of renal events demonstrated that the patients who were started on a higher than protocol‐recommended dose were more likely to have renal events, which is consistent with the known safety profile of deferasirox (see below).

AEs with a suspected relationship to deferasirox were reported in 54 patients (62.8%) on DT and 41 patients (47.1%) on FCT, and were predominantly (≥10%) diarrhea (DT 19.8%; FCT 13.8%), increased UPCR (DT 10.5%; FCT 17.2%), abdominal pain (DT 16.3%; FCT 8.0%), vomiting (DT 15.1%; FCT 4.6%), and nausea (DT 12.8%; FCT 9.2%). One patient with MDS receiving FCT died during the study as a result of febrile neutropenia; this was not suspected to be related to study drug.

Serious AEs (SAEs) were reported in 13 patients (15.1%) receiving DT and 16 patients (18.4%) receiving FCT. Most SAEs were reported for only one patient; SAEs of accidental overdose, diarrhea, and sepsis were each reported for two patients receiving FCT. Five patients receiving DT and three patients receiving FCT had SAEs suspected to be related to study drug, most frequently GI disorders (DT, n = 2; FCT, n = 1); events were considered severe in two patients receiving DT (abdominal pain and dehydration/viral infection/renal impairment) and in none receiving FCT.

Six patients in the deferasirox DT arm (7.0%) and five patients in the deferasirox FCT arm (5.7%) had one or more AEs where study drug was discontinued. GI‐related disorders were the most common reason for study drug discontinuation in patients receiving DT (n = 4 [4.7%]; abdominal pain, abdominal pain upper, diarrhea, dysphagia), whereas only one patient receiving FCT discontinued treatment because of a GI event (Crohn's disease).

3.2.2. Laboratory parameters

Mean SCr increased initially but stabilized during the study, remained within the normal range, and was similar with both formulations. In most patients with normal values at baseline, SCr remained below ULN during the study (DT 85.9% and FCT 90.8%); two consecutive SCr values >ULN and >33% increase from baseline were reported in four and three patients in the DT and FCT groups, respectively. CrCl remained greater than 60 mL/min during the study for most patients (DT 87.8% and FCT 91.9%). Of 11 patients receiving DT and eight receiving FCT who experienced at least one CrCl value <60 mL/min during the study, four patients and one patient, respectively, had values below this threshold at baseline.

Mean ALT and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) remained stable throughout the study; baseline and end of treatment values were similar with both formulations. Similar proportions of patients (∼18%) in both treatment arms who had ALT/AST values in the normal range at baseline had at least one value >ULN during the study.

There were no signs of progressive UPCR increases from baseline to end of treatment in either treatment group, although there was a transient peak in mean UPCR (0.36 mg/mg [median 0.19, range 0.04‐1.98]) observed at week 9 in the FCT arm. Of patients with UPCR <1.0 mg/mg at baseline, 7.2% of patients receiving DT and 16.1% of patients receiving FCT experienced one value >1.0 mg/mg during the course of the study.

The proportions of patients with post‐baseline laboratory parameters meeting the specified criteria for notable values were similar for both formulations (Supporting Information Table S1).

3.2.3. Post‐hoc evaluation of patients with renal events (renal adverse events and abnormal renal laboratory parameters)

For the purpose of this detailed evaluation of patients with renal AEs and abnormal renal laboratory parameters, a patient was classified as experiencing a renal event if one of the following criteria was met: a reported AE with the following preferred terms: renal impairment, blood creatinine increased, blood creatinine abnormal, glomerular filtration rate decreased, UPCR increased, proteinuria, UPCR abnormal, urine albumin/creatinine ratio increased; SCr >33% above baseline and >ULN in two consecutive values at least 7 days apart; recalculated CrCl <40 mL/min; two consecutive UPCR values >0.5 mg/mg at least 48 hours apart. Fifty‐nine patients met one or more of these criteria: 26 patients receiving DT and 33 patients receiving FCT. Evaluation of the starting dose against the study protocol‐recommended dose range revealed that more patients receiving FCT were started on doses above the protocol‐recommended range (n = 23; 26.4%) than patients receiving DT (n = 8; 9.3%; Table 4).

Table 4.

Evaluation of starting dose of study drug for all patients and patients with renal events

| Starting dosea | All patients, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| All patients, n (%) | Deferasirox DT (N = 86) | Deferasirox FCT (N = 87) |

| Below protocol‐recommended dose | 10 (11.6) | 4 (4.6) |

| Protocol‐recommended dose | 68 (79.1) | 60 (69.0) |

| Above protocol‐recommended dose | 8 (9.3) | 23 (26.4) |

| Patients with renal event, n/N (%) | DT (n = 26) | FCT (n = 33) |

| Below protocol‐recommended dose | 1/10 (10.0) | 3/4 (75.0) |

| Protocol‐recommended dose | 21/68 (30.9) | 20/60 (33.3) |

| Above protocol‐recommended dose | 4/8 (50.0) | 10/23 (43.5) |

| Patients without renal events, n/N (%) | DT (n = 60) | FCT (n = 54) |

| Below protocol‐recommended dose | 9/10 (90.0) | 1/4 (25.0) |

| Protocol‐recommended dose | 47/68 (69.1) | 40/60 (66.7) |

| Above protocol‐recommended dose | 4/8 (50.0) | 13/23 (56.5) |

Chelation‐naïve patients: starting dose required to be within ± 15% of 14 and 20 mg/kg/day doses for FCT and DT, respectively. Prior chelated patients: Starting dose required to be within 15% of an equivalent FCT or DT dose corresponding to their pre‐washout dose. The maximum starting dose allowed was +15% of 28 and +15% of 40 mg/kg/day doses for FCT and DT, respectively.

Of all the patients who experienced renal events, 30.3% (n = 10/33) of patients receiving FCT and 15.4% (n = 4/26) of patients receiving DT started on a higher than recommended dose. When patients started at a correct starting dose, similar proportions of renal AEs were seen in each arm: n = 20/60 patients (33.3%) receiving FCT and n = 21/68 (30.9%) receiving DT.

3.3. Evaluation of changes in serum ferritin levels

In patients receiving DT, median serum ferritin (range) decreased from 2485 (915‐8250) ng/mL at baseline to 2064 (439‐16 500) ng/mL at end of treatment. In patients receiving FCT, median serum ferritin (range) decreased from 2983 (939‐8250) ng/mL to 2302 (443‐8250) ng/mL. The absolute change in median serum ferritin (range) in patients receiving FCT was −350 (−4440 to 3572) ng/mL and in those receiving DT was −85.5 (−2146 to 8250) ng/mL; these correspond to a relative change of −14.0% with FCT and −4.1% with DT.

3.4. Clinical PK

Deferasirox pre‐dose concentrations (C trough) at steady state were similar to both DT and FCT formulations throughout the study. Geometric mean of C trough (dose‐adjusted) for DT and FCT were 25.2 µmol/L versus 23.4 µmol/L at week 3, 26.1 µmol/L versus 23.6 µmol/L at week 13, and 32.3 µmol/L versus 31.4 µmol/L at week 21, respectively.

Geometric mean deferasirox concentrations 2 h post‐dose at steady state were slightly higher with FCT than DT at week 3 (80.9 vs. 69.4 µmol/L), week 13 (85.5 vs. 67.8 µmol/L), and week 21 (92.7 vs. 71.8 µmol/L).

PK variability shown as coefficient of variation of geometric mean was smaller with FCT than DT. Results were similar with or without dose normalization, which suggest that overall exposure to deferasirox was similar for both formulations, with slightly higher post‐dose concentrations with FCT. PK results observed in this study were consistent with data previously obtained in healthy volunteers (data on file).

3.5. Patient‐reported outcomes

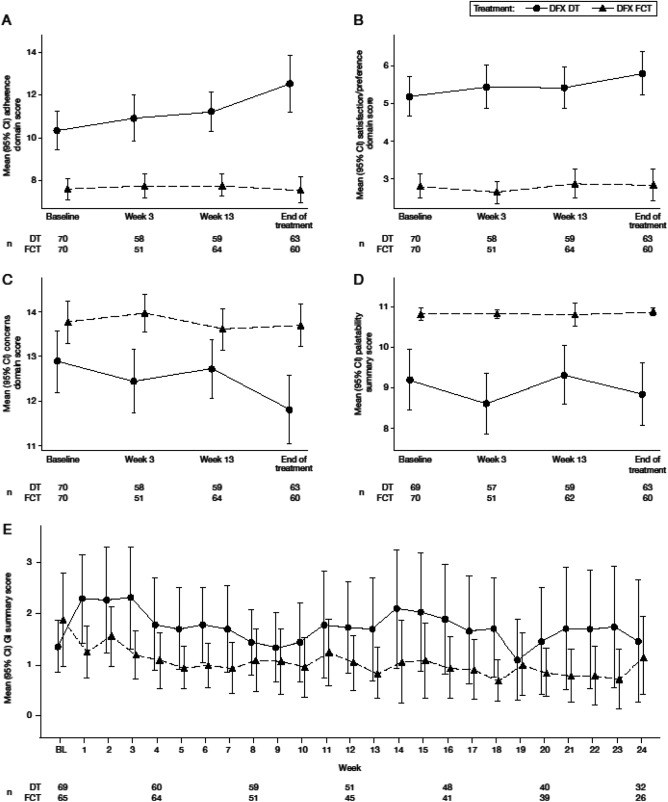

Completion rates for PRO instruments were: ∼80% for the PRO questionnaire at the beginning of the study, reducing to ∼70% by month 24; ∼60% reducing to ∼30% for the compliance diary; and ∼70% reducing to ∼35% for the GI symptom diary. Throughout the 24‐week study period, for modified SICT, patients receiving FCT reported consistently greater adherence (attributable to: finding it easier to remember to take medication, thinking less often about stopping medication, following instructions from the doctor more closely, finding medication easier to take, being less bothered by the time taken to prepare medication and the waiting time before eating), greater satisfaction/preference (in general and also with administration of medicine), and consistently fewer concerns (attributable to: being less worried about not swallowing enough medication, experiencing fewer limitations in daily activities, feeling less concerned about side effects) than patients receiving DT (Figure 1A‐C). The difference in score between the two formulations was >1 point (minimal important difference [MID]) for all three domains at every visit, and no overlapping CIs at almost every timepoint, indicating a clinically meaningful difference between formulations. Patients receiving FCT reported consistently higher satisfaction on palatability scores, reporting no taste or aftertaste and that they were able to swallow the full amount of medicine with the right amount of liquid compared with patients receiving DT (Figure 1D). The overall GI symptom scores were low for both formulations, indicating patients experienced very little trouble/concern associated with GI symptoms (Figure 1E). Results favored FCT with patients reporting near‐perfect scores for all three modified SICT domains and palatability.

Figure 1.

Mean domain scores for patient‐reported outcomes (adherence, satisfaction/preference, and concern) (A‐C), mean palatability score (D), and mean gastrointestinal symptom scores (E). For adherence (A; scale 6‐30), satisfaction/preference (B; scale 2‐10), and GI symptoms (E; scale 0‐50), higher scores indicate worse outcomes/symptoms. For concern (C; scale 3‐15) and palatability (D; scale 0‐11), higher scores indicate fewer concerns and better palatability. A‐D, baseline was defined as week 2 assessment. If missing, then the week 3 assessment was considered baseline; E, baseline was defined as week 1 score. If missing, then the week 2 score was considered baseline. BL, baseline.

4. Discussion

The ECLIPSE study evaluated safety, PK, and PRO of the original deferasirox DT formulation and the new dose‐adjusted FCT formulation, which contains the same active substance and can be swallowed without the need to disperse into a suspension, in patients with lower‐risk MDS and thalassemia. The results demonstrate similar safety profiles for FCT and DT, both consistent with the known profile of deferasirox, with no new safety signal identified. The exposure‐adjusted GI AE rate and incidence of severe GI AEs provide evidence for acceptable GI tolerability. Combined with the simpler and more convenient mode of administration of the FCT, these factors likely contributed to the observations that more patients receiving FCT remained on treatment for at least 12 weeks and were more compliant with treatment. Although the study was only 6 months, a reduction in serum ferritin of 14% and 4.1% was observed with FCT and DT, respectively. In addition to greater compliance with treatment, it was found that a larger proportion of patients in the FCT group received a higher than recommended dose, which could have contributed to the observed serum ferritin reduction. Further analyses are warranted to specifically determine the effects of deferasirox FCT on the serum ferritin levels.

The PRO analyses, using instruments validated within this trial, show a benefit in favor of deferasirox FCT in all domains for the modified SICT, including greater adherence, greater satisfaction, fewer concerns, and better palatability with respect to taste and ability to consume medicine; patients receiving FCT achieved clinically meaningful and important differences compared with patients receiving DT for all domains. Overall, all patients were satisfied with their medicine during the study period; satisfaction scores were higher with deferasirox FCT compared with DT at all visits.

GI disturbances are often reported during clinical evaluation of deferasirox, usually mild‐to‐moderate and occurring early in the course of treatment.16 As deferasirox FCT can be taken with a light meal and also lacks the excipients lactose and sodium lauryl sulfate, both found in the original DT formulation and possibly implicated in GI AEs, it was expected that deferasirox FCT would show improved GI tolerability. Although similar numbers of patients in each arm experienced one or more GI AEs or received dose adjustments as a result of GI AEs, 12.8% and 4.6% of patients in the deferasirox DT and FCT groups, respectively, experienced severe GI AEs (including diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain) and four patients (DT) and one patient (FCT) discontinued treatment because of GI AEs. These results were reflected in the PROs: patients receiving FCT reported little or no concern with GI symptoms. Taken together, these results suggest that the GI tolerability profile may be improved with FCT compared with DT, which could be because of the change in excipients and/or the ability to take the medicine with a light meal. Further insight should be gained once longer‐term data are available.

In the current study, more patients receiving FCT experienced renal AEs or abnormal renal parameters than those receiving DT, although the number of patients with renal laboratory values in the notable/extended ranges were either similar or lower in the FCT arm. Renal laboratory changes and AEs are well characterized with deferasirox therapy and are generally mild, non‐progressive, and reversible.17 As such, the observed imbalance in reported renal events between the two treatment arms are likely attributed to a larger proportion of patients in the FCT group receiving a higher than recommended dose, as well as non‐adherence to protocol‐recommended dose modifications and (renal) exclusion criteria during the relatively short duration of the study. Longer‐term follow‐up of patients is warranted to confirm whether the FCT has any notable effect on the occurrence of renal events.

This study demonstrates that to achieve optimal treatment benefits from iron chelation with deferasirox, it is highly recommended to manage and monitor patients in accordance with the product label. In particular, the results highlight the importance of ensuring that patients start treatment on the correct dose. Care should be taken when switching patients to FCT to ensure a dose equivalent to their previous iron chelation treatment is administered (eg, FCT doses are 30% lower than DT doses, conversion factor 1.43). Evaluation of PK data in this study confirmed that patients treated with dose‐adjusted FCT achieved comparable exposure to that achieved with DT, with similar pre‐dose deferasirox levels and slightly higher 2‐h post‐dose levels observed with FCT.

Patient survival can be affected by compliance with medical treatment, particularly iron chelation, which in turn can be influenced by a number of factors, including patient satisfaction with/preference for their medication.3, 18 Patient satisfaction rates for deferasirox DT have been reported to be as high as ∼90%,19 yet studies have shown that most patients dislike the mode of administration for deferasirox DT and would prefer to be able to take their medication with food.20 Barriers such as these likely contribute to a reduced patient‐reported adherence to deferasirox DT of 67‐86%.21 To improve patient satisfaction and palatability of medication, and thereby adherence, the new FCT was developed to be taken with or after a light meal and was manufactured without sodium lauryl sulfate. In this study, validated methods indicated that compliance was higher with deferasirox FCT than with DT, with patients reporting better palatability, greater adherence, and fewer concerns with deferasirox FCT than with DT. The results show that patient satisfaction and adherence is improved with FCT; long‐term studies will be valuable to confirm that this translates into improved clinical outcomes, with fewer iron overload‐related complications and improved survival.

In this study in patients with TDT or IPSS‐R very‐low‐, low‐, or intermediate‐risk MDS, FCT demonstrated a short‐term safety profile consistent with the known deferasirox DT profile. Patients receiving FCT had better treatment compliance and experienced a reduction in serum ferritin, which are promising outcomes for continuing treatment, though longer‐term evaluation of the FCT is still required to support these results. This study suggests that deferasirox FCT offers patients an improved formulation that does not require administration in a fasting state, has better palatability, and minimal concerns associated with GI tolerability. However, it appears that in some patients, there were errors in converting the dose from the DT to the FCT and clinicians are advised to closely follow the recommendations in the prescribing information. Overall, patient satisfaction was enhanced with deferasirox FCT, which may improve adherence, thereby reducing frequency and severity of iron overload‐related complications.

Author contributions

ATT, RO, SP, AKo, GBR, AKa, A‐SG, and JBP served as investigators in this trial, enrolling patients. AC, RMH, and VH contributed to the analysis, interpretation, and reporting of the trial data. MW served as the trial statistician. All authors contributed to data interpretation, reviewed and provided their comments on this manuscript, and approved the final version.

Conflict of interest

ATT reports receiving research funding and honoraria from Novartis; RO reports receiving honoraria from Novartis and Apopharma; SP reports receiving honoraria from Novartis; AKa reports receiving research funding and participating in advisory boards and educational forums sponsored by Novartis; AKo reports receiving honoraria from Novartis, Amgen, and Janssen, and consultancy for Gilead, Roche, and Celgene; JBP reports consultancy, receiving research grant funding and honoraria from Novartis Pharmaceuticals, consultancy and honoraria from Shire, and consultancy for Celgene. JBP is supported by the NIHR University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre; AC, MW, RMH, and VH were full‐time employees of Novartis at the time of these analyses; A‐SG and GBR have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supporting information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information Figure S1

Supplementary Information Table S1

Supplementary Information Coinvestigator Appendix

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Novartis Pharma AG. We would like to thank all of the study investigators, the full list of investigators can be found in supplementary information. Authors would also like to thank Aiesha Zia of Novartis Pharma AG for statistical support. Authors thank Catherine Risebro, PhD, of Mudskipper Business Ltd. for medical editorial assistance. Financial support for medical editorial assistance was provided by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Taher AT, Origa R, Perrotta S, et al. New film‐coated tablet formulation of deferasirox is well tolerated in patients with thalassemia or lower‐risk MDS: Results of the randomized, phase II ECLIPSE study. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:420–428. 10.1002/ajh.24668

Funding Information Novartis Pharma AG, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

References

- 1. Galanello R, Origa R. Beta‐thalassemia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gabutti V, Piga A. Results of long‐term iron‐chelating therapy. Acta Haematol. 1996;95:26–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Delea TE, Edelsberg J, Sofrygin O, et al. Consequences and costs of noncompliance with iron chelation therapy in patients with transfusion‐dependent thalassemia: a literature review. Transfusion. 2007;47:1919–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Escudero‐Vilaplana V, Garcia‐Gonzalez X, Osorio‐Prendes S, et al. Impact of medication adherence on the effectiveness of deferasirox for the treatment of transfusional iron overload in myelodysplastic syndrome. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41:59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brittenham GM, Griffith PM, Nienhuis AW, et al. Efficacy of deferoxamine in preventing complications of iron overload in patients with thalassemia major. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:567–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Modell B, Khan M, Darlison M. Survival in β‐thalassaemia major in the UK: data from the UK Thalassaemia Register. Lancet. 2000;355:2051–2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cappellini MD, Bejaoui M, Agaoglu L, et al. Prospective evaluation of patient‐reported outcomes during treatment with deferasirox or deferoxamine for iron overload in patients with β‐thalassemia. Clin Ther. 2007;29:909–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Osborne RH, De Abreu LR, Dalton A, et al. Quality of life related to oral versus subcutaneous iron chelation: a time trade‐off study. Value Health. 2007;10:451–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Galanello R, Piga A, Forni GL, et al. Phase II clinical evaluation of deferasirox, a once‐daily oral chelating agent, in pediatric patients with β‐thalassemia major. Haematologica. 2006;91:1343–1351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Piga A, Galanello R, Forni GL, et al. Randomized phase II trial of deferasirox (Exjade®, ICL670), a once‐daily, orally‐administered iron chelator, in comparison to deferoxamine in thalassemia patients with transfusional iron overload. Haematologica. 2006;91:873–880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cappellini MD, Cohen A, Piga A, et al. A phase 3 study of deferasirox (ICL670), a once‐daily oral iron chelator, in patients with beta‐thalassemia. Blood. 2006;107:3455–3462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Porter J, Galanello R, Saglio G, et al. Relative response of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes and other transfusion‐dependent anaemias to deferasirox (ICL670): a 1‐yr prospective study. Eur J Haematol. 2008;80:168–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vichinsky E, Onyekwere O, Porter J, et al. A randomized comparison of deferasirox versus deferoxamine for the treatment of transfusional iron overload in sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2007;136:501–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Trachtenberg FL, Gerstenberger E, Xu Y, et al. Relationship among chelator adherence, change in chelators, and quality of life in thalassemia. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:2277–2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Novartis Pharmaceuticals . JADENU® (deferasirox) US Prescribing Information. 2015. Available at: www.pharma.us.novartis.com/product/pi/pdf/jadenu.pdf. Last accessed February 2, 2017.

- 16. Vichinsky E. Clinical application of deferasirox: practical patient management. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:398–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Piga A, Fracchia S, Lai ME, et al. Deferasirox effect on renal haemodynamic parameters in patients with transfusion‐dependent beta thalassaemia. Br J Haematol. 2015;168:882–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cappellini MD. Long‐term efficacy and safety of deferasirox. Blood Rev. 2008;22(Suppl 2):S35–S41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vichinsky E, Pakbaz Z, Onyekwere O, et al. Patient‐reported outcomes of deferasirox (Exjade®, ICL670) versus deferoxamine in sickle cell disease patients with transfusional hemosiderosis: substudy of a randomized open‐label Phase II trial. Acta Haematol. 2008;119:133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goldberg SL, Giardina PJ, Chirnomas D, et al. The palatability and tolerability of deferasirox taken with different beverages or foods. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:1507–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Porter J, Bowden DK, Economou M, et al. Health‐related quality of life, treatment satisfaction, adherence and persistence in beta‐thalassemia and myelodysplastic syndrome patients with iron overload receiving deferasirox: results from the EPIC clinical trial. Anemia. 2012;2012:297641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information Figure S1

Supplementary Information Table S1

Supplementary Information Coinvestigator Appendix