Abstract

Background

Social media can support people with communication disability to access information, social participation and support. However, little is known about the experiences of people with traumatic brain injury (TBI) who use social media to determine their needs in relation to social media use.

Aims

To determine the views and experiences of adults with TBI and cognitive‐communication disability on using social media, specifically: (1) the nature of their social media experience; (2) barriers and facilitators to successful use; and (3) strategies that enabled their use of social media.

Methods & Procedures

Thirteen adults (seven men, six women) with TBI and cognitive‐communication disability were interviewed about their social media experiences, and a content thematic analysis was conducted.

Outcomes & Results

Participants used several social media platforms including Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and virtual gaming worlds. All but one participant used social media several times each day and all used social media for social connection. Five major themes emerged from the data: (1) getting started in social media for participation and inclusion; (2) drivers to continued use of social media; (3) manner of using social media; (4) navigating social media; and (5) an evolving sense of social media mastery. In using platforms in a variety of ways, some participants developed an evolving sense of social media mastery. Participants applied caution in using social media, tended to learn through a process of trial and error, and lacked structured supports from family, friends or health professionals. They also reported several challenges that influenced their ability to use social media, but found support from peers in using the social media platforms. This information could be used to inform interventions supporting the use of social media for people with TBI and directions for future research.

Conclusions & Implications

Social media offers adults with TBI several opportunities to communicate and for some to develop and strengthen social relationships. However, some adults with TBI also reported the need for more information about how to use social media. Their stories suggested a need to develop a sense of purpose in relation to using social media, and ultimately more routine and purposeful use to develop a sense of social media mastery. Further research is needed to examine the social media data and networks of people with TBI, to verify and expand upon the reported findings, and to inform roles that family, friends and health professionals may play in supporting rehabilitation goals for people with TBI.

Keywords: traumatic brain injury, social media, rehabilitation

What this paper adds

What is already known on the subject

Little is known about the experiences of people with TBI using social media or what may help or hinder them in its use. Understanding more about the experiences of people with TBI is important to developing interventions that facilitate their communication and inclusion in online environments.

What this paper adds to existing knowledge

This research presents the views of people with TBI and an analysis of their experiences and views in relation to using social media. The findings can be used to inform development of TBI rehabilitation goals and development of social media supports for people with TBI.

What are the potential or actual clinical implications of this work?

With growing expectations that technology and social media be incorporated into rehabilitation services, a person‐centred approach to services is needed to support the use of social media. The findings of this study inform future research and applications to assist people with TBI to use social media not only for communication but also for information exchange and access to social supports.

Introduction

People with traumatic brain injury (TBI) use social media to exchange information, converse and share their experiences of life after TBI (Brunner et al. 2018). While the social perceptions of communication and social interaction online are evolving and expanding (Baker‐Sparr et al. 2018), social media use is associated with a number of risks, including the risk on mental health of internet addiction (Oberst et al. 2017), and risks related to exposure to or engagement in cyber‐victimization (e.g., stalking, cyberbullying, trolling, scams, identity theft) (Jenaro et al. 2018).

Conversely, there are several benefits associated with using social media, including for people with communication disability (Hemsley et al. 2014). Social media offers users more time to respond than face‐to‐face encounters, is tolerant of incorrect spelling or grammar, and involves both text‐based and multimedia communication which could prove an advantage for people with limited speech (Hemsley et al. 2017). However, with population level studies lacking (Brunner et al. 2015) it is not known how many people with TBI use social media or for what purpose. Reportedly, they use a wide variety of platforms (Baker‐Sparr et al. 2018, Brunner et al. 2018). Therefore, it is important to understand how people with TBI can be included in social media networks, particularly given their reduced opportunity for social interaction following TBI (Brunner et al. 2017, 2018).

Cognitive‐communication impairments after TBI vary greatly across the population of people with TBI, and can affect a person's ability to converse, develop or maintain relationships, and reconstruct a sense of self after their injury (Douglas 2013). Facilitating increased resilience in people with TBI is known to help improve social participation and rehabilitation outcomes (Dumont et al. 2004, Kreutzer et al. 2016, Lukow et al. 2015). However, to date there is no information available about how people with TBI might respond to risks or dangers they encounter in social media, nor how their resilience might impact on their development of cyber‐resilience and hence safe use of social media. Several factors are proposed to impact on a person's development of social media safety, and how they respond to and recover from adverse events (e.g., cyberbullying). These factors include their emotional intelligence, agreeableness, empathy, coping skills, optimism and social supports (Jenaro et al. 2018). In turn, these characteristics influence their cyber‐resilience, an ability to respond and recover from negative online experiences (Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) 2015), and as such are important in using social media safely.

There is good reason to think that people with TBI might struggle to communicate in social media as they have communication styles that might be amplified by features of social media, particularly its enablement of increasing immediacy, visibility and spreadability of messages (boyd 2014). As a result of changes in their cognitive‐communication skills, people with TBI are described as being on a continuum of skills reflecting ‘impoverished’ communication with substantially limited language output through to ‘excessive’ communication, with verbosity and tangentiality evident in their conversations (Sim et al. 2013, Tate 1999). It is not known how cognitive‐communication impairments affect social media use, or whether social media might in fact facilitate moderation of these communication styles. While information on social media is abundant, it is also ephemeral and hard to find, increasing demands on the user's memory, sorting, curation and organizational skills. Also, a person's cognitive impairments after TBI may alter the ways that they learn to manage both the challenges of finding and keeping track of information sources, and how to use and adjust to the frequent changes in social media platforms (Baker‐Sparr et al. 2018, Brunner et al. 2017).

To date, research on the use of social media by people with TBI and cognitive‐communication impairments has focused on risks and barriers to using social media (Brunner et al. 2017) and there has been little attention paid to the views or experiences of people with TBI on using social media and managing its various risks to safety or enjoyment (Brunner et al. 2015). As a result, it is not known what supports they need or want in relation to the safe use of social media and hence inclusion in socially networked communities (Brunner et al. 2017, 2018). Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the needs and experiences of people with TBI on their use of social media, specifically: (1) the nature of the experience and influences over their use of social media; (2) barriers and facilitators to successful use; and (3) strategies that enabled their use of social media in the context of their TBI and changes in cognitive‐communication. This information could inform the design of interventions to support people with TBI to participate in social media, and directions for future research exploring the use of social media in rehabilitation.

Materials and methods

The study design employed an iterative thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006). Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the universities involved.

Recruitment

Purposive sampling was used to recruit adults with TBI and cognitive‐communication disorder and who used social media. Recruitment materials were posted on social media and sent out by e‐mail using a TBI research register. The sample obtained enabled exploration of a wide range of experiences and views, without attempting to determine the most frequent or common experiences (Patton 2015).

Data collection

Interviews

A topic guide (see appendix A) was developed to guide conversational‐style interviews exploring participants’ use of social media (Hemsley et al. 2014), and included demographic questions and seven broad categories of questions (de Leeuw et al. 2008). The interviews were designed to enable participants to tell their own social media stories and elaborate on their lived experiences (Patton 2015). The first author, a speech pathologist experienced in working with people with TBI, conducted the interviews, either online using Skype (n = 10), in‐person (n = 1) or by phone (n = 2). The digitally audio‐recorded interviews lasted from 21 to 120 min. At the beginning of each interview, demographic questions obtained information on participants’ age, social context, injury and employment history, cognitive‐communication skills, and current social media platforms used. A range of strategies were used to support each participant's communication during the interviews, including: use of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC); offering rest breaks or conducting the interview across two occasions; asking for specific examples to elicit more detailed responses; repeating or clarifying questions; and confirming or summarizing participants’ responses (Douglas 2013, Hemsley et al. 2014). The first author transcribed the audio‐recording verbatim and de‐identified the transcripts for analysis. Interview transcripts were examined by the first author to identify participants as using either impoverished or excessive communication (Sim et al. 2013, Tate 1999), a judgement that was primarily determined by the number of words used per independent clause in sentence production (Coelho et al. 2013).

Data analysis

The first author made detailed field notes during and after each interview, documenting reflections for future discussion with the researchers, and interpretive notes on content (Creswell 2014). This supported a constant comparison method of analysis as data collection proceeded (Tracy 2013). Following the interviews, the first author read and re‐read the transcripts, to look for a range of alternative meanings in the texts, and wrote a two‐to‐three‐page draft summary of each transcript (Patton 2015). The first and final authors discussed these summaries, agreed on their interpretations and sent each participant a copy of their transcript with an invitation to verify, change, add or remove any details contained within it before further analysis of the data. In total, six of the 13 participants responded and verified the transcripts (n = 4), or suggested minor changes (n = 2) which were incorporated into the summaries.

Using NVivo software to store and retrieve the data during analysis, open codes were applied to the transcripts to reflect meanings in the words, phrases, sentences and passages (Elo and Kyngäs 2008). An iterative approach to the analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006) involved the first author drafting and periodically returning to a mind map to model the concepts in the data (Patton 2015), returning to coding (Elo and Kyngäs 2008) and discussing these codes and the evolving model with colleagues (Creswell 2014). Finally, the list of open codes was examined to identify categories of codes and component themes within and across the interviews, which represented the participants’ experiences and views (Braun and Clarke 2006). The thematic results are presented with illustrative quotations (Riessman 2008) to increase the plausibility of the findings (Patton 2015), and relationships between the thematic categories are explored (Patton 2015).

Results

Participants

Seven men (54%) and six women (46%) took part in the study. Participants’ average age was 33 years (range = 20–72 years). Six were employed, two were students and five were unemployed. On average, participants experienced their TBI at 22 years of age (range = 13–33 years) and more than 10 years had passed since their injury (range = 1–59 years). They had acquired a TBI as a result of a motor vehicle accident (n = 6), sporting injury (n = 4), assault (n = 1), work accident (n = 1) or arteriovenous malformation (AVM) haemorrhage (n = 1). Although not formally classified as a TBI (Sacco et al. 2013), a woman with AVM‐related brain injury was included as she had aphasia, cognitive‐communication impairment and identified as having a TBI. Two participants had also experienced brain trauma since their initial TBI: one had neurosurgery to reduce TBI‐related tremor, resulting in physical disability, and another had a benign brain tumour removed.

Participants used several social media platforms, including Facebook (n = 13), Twitter (n = 6), Instagram (n = 6) and Snapchat (n = 5); and various other sites: blogs, instant messaging (e.g., Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp), dating apps (e.g., Tinder), Skype (or other similar platform), e‐mail, virtual gaming worlds, LinkedIn, MeChat, YouTube or Spotify (n = 2). All but one participant (P13) used multiple social media platforms, with most (n = 11) using them quite frequently (more than once a day). Two participants used communication supports in the interview: one used AAC (an alphabet board, a speech generating device and mobile communication technology) and another participant's spouse provided occasional support in word retrieval. Although most (n = 11) participants reported that their communication had improved greatly since their TBI, all reported having cognitive‐communication impairments and these were also evident in the interviews. Overall, 38% (n = 5) of the participants had an impoverished conversational style in that they offered short responses and often had difficulty elaborating their responses; and 62% of the participants (n = 8) presented with an excessive conversational style, speaking at length and being tangential with restricted content despite the large number of words spoken.

Content themes

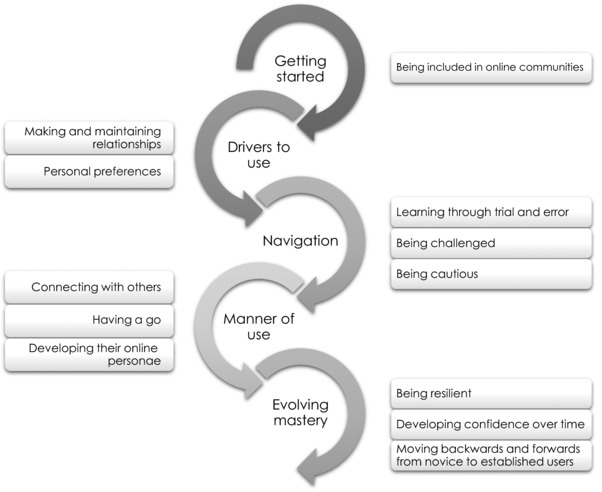

Five major content themes emerged from the data. These are represented in figure 1, which highlights the progression and return to getting started to movement through usage to an evolving social media mastery.

Figure 1.

Cyclical stages in an evolving mastery of social media.

Getting started in social media for participation and inclusion

Many participants recalled getting started in their use of social media because it was a popular activity (n = 9) and/or because of their fear of missing out (Oberst et al. 2017). The most common view across the interviews was that using social media was the community norm: ‘Like everyone was on Facebook … everyone was doing it’ (P13). Indeed, all but one participant had been using Facebook before their TBI, and using social media had been a part of their lives for several years. While almost half the participants had friends or new acquaintances set up accounts on their behalf (n = 6), others reported that friends or family had encouraged them to set up their social media accounts themselves (n = 4).

Reflecting their desire to ‘join the masses’, most participants viewed social media as being a good way to keep in touch with their friends and family (n = 12) and to observe, as P10 said: ‘I like to see pictures of people's lives.’ Three participants enjoyed following people of public interest (n = 3), such as celebrities, to ‘watch Kelly Slater and see what he's up to’ (P3). One (P2) got interested in social media when he was ‘finding out about different ways of communication’ as he wanted to tell the world what was happening to him. Another (P12) used Skype to access aphasia therapy, informally tutor other people with aphasia in communication, and talk with family and friends.

A few participants reported that they got into social media, especially online gaming (n = 2), because it was fun and ‘it makes my life less boring’ (P1). Some (n = 3) felt that ‘it's a time‐waster sort of thing’ (P4), with one participant stating she would look at it in bed when she woke up every day, ‘probably oh my god, probably an hour’ (P12). P9 found that after a career change, using social media had provided her with another outlet: ‘when I got out of [working in] radio … Facebook became my radio show’. A majority of participants (n = 11) reported that they enjoyed listening to or seeing others online with similar interests, such as music, technology, football, gaming, art and politics. Additionally, it was seen as another way of accessing information and support after their brain injury, as P7 explained: ‘I set up a separate one [Facebook account] to join lots of Facebook groups for other survivors.’

Drivers to continued use of social media

Purposes of use

Making and maintaining relationships

As reflected in the theme of getting started, participants were driven or motivated to keep using social media for social connection and with the ultimate purpose of connecting with others (n = 13), and ‘keeping in touch with friends’ (P6). Indeed, one participant (P11) reported reliance on social media for this purpose, and that she ‘wouldn't be able to interact with my friends without it’. Another felt that she had ‘formed some really good relationships within social media’ (P9). All participants mentioned the importance of being able to use social media to watch family, friends and other members of society. Participants also wanted to be able to tell the world what is happening and to share their stories (n = 5) and ‘talk to people overseas when needed’ (P3) (n = 4). It gave them opportunities for interaction (n = 3), dating (n = 4), support after their TBI (n = 3), to access therapy (n = 1, via Skype), to support conversations (n = 1) and to reduce social isolation: ‘So I may sit in my house all alone, all day long and not speak to another person … but yet I've interacted with all these different people, the way I do it on Facebook, it's positive’ (P9).

Altruism, advocacy and activism

Social media provided participants with a platform to help other people with brain injury (n = 2) and to follow friends and people with whom they shared similar beliefs or political persuasion. Two reported social media enabled them to read and comment on what they saw as serious issues, and others found it helpful to connect with local representatives and advocate for change (n = 2). However, only one (P7) had started blogging to raise awareness of brain injury, and another (P10) reported that she would like to do more advocacy in social media in the future but found it tiring cognitively.

Benefits of use

Related to their central purpose for using social media, all participants reported obtaining benefits through enhanced connectedness with family and friends (n = 13), and also being able to communicate ‘with pretty much anybody in the entire world’ (P7). Several (n = 7) described the benefit of some platforms facilitating a wider variety of connections: ‘you can follow whoever you want rather than someone you know’ (P5). All the participants found social media to be ‘fun’ and interesting as there were plenty of different topics being discussed, and they could listen to different people and diverse views. It provided a way of being social even if isolated at home, and enabled them to organize their social calendar and remember things: ‘because it's all there, like gig dates and stuff’ (P6). For P1, playing people in online games was an enjoyable challenge in that it was much harder and hence more engaging than playing the computer. Two participants viewed chatting online as being ‘easier than what a, like a physical conversation would be’ (P13) as there was less pressure to respond. As P13 said, ‘you've got thinking time when you're having a chat online … but in a conversation it's more impromptu, it's more on the spot’.

Enablers of use

Seven participants explained that the encouragement they received from their friends, family and online support networks, along with their interactions online, facilitated their use of social media. The majority (n = 10) reported that friends or family members had helped them to get set up in using social media. However, this did not necessarily mean that participants knew how to use the platform, and five participants described seeking tips and support in how to use the platforms from acquaintances in social media who were willing to help. One participant (P11) reported that her enjoyment in interacting with friends online influenced how often she used social media: ‘Snapchat I have only just started to use frequently … and that's only because I've got friends who I quite enjoy interacting with.’ If feeling vulnerable, she drew on her close friends to be ‘sounding boards’ or to check and approve some of her posts before publication. Two participants considered that the social media platforms supported successful use by enabling asynchronous communication and that software applications (apps) on mobile devices also helped to ease cognitive demands (e.g., scheduling tweets, screen readers). Using internet search engines to troubleshoot and search for help online also enabled continued use when challenges were encountered.

Personal preferences in use

While communicating on social media provided some advantage to those who needed more time to think before formulating a written response, one participant with persistent written language difficulties preferred to speak in‐person or on the phone. Participants did not generally like all social media platforms equally, and some expressed using a narrow range or preferring to avoid particular platforms. Two participants highlighted a preference for using Facebook over Twitter due to lack of restrictions on the length of posts: ‘In Facebook, there's no limit, it's lovely’ (P1); and its visual appeal easing access in terms of reading: ‘Facebook is more laid out like an online magazine that your friends put out’ (P9).

Most participants were content with how much they used social media (n = 10), however a few reported that they would like to use social media more, for playing online games (n = 1) or for professional purposes (n = 2). While one participant preferred to use social media for news and politics than for interacting socially, two used social media only to connect with familiar people: ‘All friends or someone that I know, so no strangers’ (P5). One participant preferred closed social media groups as it meant she need not necessarily disclose her brain injury publicly and this provided a feeling of safety: ‘so it was a place where I was safe, and because it was this closed little group and we could communicate in this thread’ (P9). Not all participants were keen to increase their use of social media either because they were already too busy (n = 5) or no longer interested: ‘There's people who use it a lot more than me but I'm not really interested in using it more’ (P8). Another participant expressed disinterest with trivial information being posted on social media: ‘I don't need to know if they got a new puppy or it doesn't really concern me if they got a new pair of shoes’ (P4).

Navigating social media

Being cautious

Overall, despite feeling vulnerable at times on social media, participants reported few things impeding their continued use of the platforms. Many reported they felt the need to impose some sensible limitations (n = 7), such as keep personal details private, thinking before posting, not posting negative things and asking for help before posting if unsure. All were aware not to post private information, such as a home address, e‐mail or banking details, and to be careful with both public and private messages: ‘I obviously don't want to post anything private, anything that you wouldn't want someone that you don't know knowing’ (P4). Participants recognized that ‘anything you put on social media is open for the whole world’ (P3). P7 avoided talking about potentially divisive topics (e.g., politics), distancing herself from people who were posting comments she did not agree with, or withholding a response rather than commenting on posts. P9 reported that she generally did not post about negative things that are happening in her personal life, for example, when unwell: ‘I don't like to go you know, I'm sick, I don't feel well today, or anything like that’ (P9).

Two participants reported that they had been taken in by online scams in terms of romantic relationships designed for extortion of money. As a result, one of these participants now kept personal information online private: ‘Things can get bad otherwise, horrible’ (P1); and the other blocked people that did not look genuine: ‘I just wipe some straight away’ (P2). Some participants exercised caution in the timing or frequency of their posts, as P11 said: ‘Well if I feel vulnerable and self‐conscious on Instagram, I'll probably be cautious of what time of day I post something out.’ Only one participant mentioned financial barriers—(P1) wanted to do more with online gaming but was limited by the associated costs of upgrades.

Being challenged

Most participants reported encountering a variety of challenges that made using social media difficult for them.

Language challenges

One participant felt that there was misinterpretation due to their language difficulties in written communication modes. Another found getting the right words to say online was a challenge due to her aphasia: ‘No like I'm just, I'm just very poor communicating’ (P12). However, the majority of challenges were not due to communication alone: they related to the participants’ emotional reactivity to using social media.

Feeling overwhelmed

Using social media had led to information overload as there was so much to explore and read. Some had been overwhelmed navigating social media timelines (n = 3) and one participant felt ‘there's so many applications I just get overwhelmed’ (P3). Others reported that it took up time and brain space (n = 2): ‘it's sort of, headspace, concentration, and I don't know, generally as I've gotten older I've sort of got less brain power’ (P5). One participant felt that with the fast pace of social media trends: ‘the way it moves so quickly I feel like you can miss out’ (P9). This difficulty with pace was also found with the constantly evolving platforms (n = 3): ‘I guess you learn to adapt as like they change’ (P10). Another participant (P9) felt overwhelmed emotionally by their exposure to so many negative events happening in the world. Additionally, an increase in social media related demands on time and attention sometimes resulted in a desire to simplify networks, as P4 reported: ‘I was just thinking of deleting everyone … that you just don't talk to anymore.’

Feeling confused

Two participants reported that they had multiple social media accounts that were not used as they found them confusing: ‘Like I have them but I don't really use them’ (P3). For example, one participant found Snapchat bewildering as it had ‘too many people’ (P3). Other participants found the differences between social media platforms confusing or found specific platforms difficult to navigate (n = 8). If they found a social media platform hard to use or confusing, participants tended to give up and returned to using a more familiar platform (n = 5): ‘Snapchat … I just don't get it, so no I don't use it’ (P7). One participant struggled so much with using social media platforms that he ‘just gave up on talking to other people’ (P3) and reverted to lurking (listening or watching in social media).

Feeling tired

Five participants reported cognitive fatigue from using social media: a few got tired from communicating (n = 2) or fatigued with reading: ‘My attention span isn't that great, part way through I just think, I can't do this anymore and just move away’ (P7). While participants valued using social media to stay up to date with current events, some became tired from thinking about the issues. Participants who reported social media‐related fatigue at times self‐imposed a time limit (‘maybe only do it for half an hour or whatever’; P3); reduced the size of their network; and even removed social media apps from mobile devices: ‘I delete it so that I don't have like reflexes of just clicking on it, like if it's not on the phone I'm like just not going to worry about it’ (P10). One participant created a closed group of friends to cope: ‘I started my “Super‐Secret Friends” group and added only the people who I knew would be helpful and positive and tried to only post and interact in that for a while’ (P9).

Being cyberbullied

Most participants felt that if they were bullied online they would ignore, block or unfriend/unfollow the bully (n = 10): ‘if I said something and people were starting to disagree in a way that might be offensive, I'd just ignore it, because nothing for me to lose’ (P5). Most participants knew something about online bullying or trolling (n = 11), but a few were not familiar with what it involved. Four of the participants (31%) had reportedly been the recipient of negative online interactions, either a scam (n = 2), trolling (n = 2) or receiving negative comments (n = 3). Two participants ignored the comments and felt that this was the best response: ‘I thought, oh well, whatever, I'll just not see him anymore’ (P3). Another participant reported that they sometimes responded in the moment, only later to go back and delete their response, and for the most part took it lightly having developed some verbal defences (P9).

Manner of using social media

Connecting, communicating and observing family and friends

Most participants valued social media platforms (mentioning Facebook, Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, Twitter and Snapchat specifically) for connecting with others and seeing what they were up to (n = 12), regardless of distance (n = 6): ‘I use Facebook to communicate with people, like overseas and stuff, abroad. … Even close to home, like reconnecting with other friends’ (P13). Three participants used the platforms to coordinate in‐person events or to follow‐up on meetings in real life. For example, P8 reported: ‘I was overseas on a group tour and met a whole new group of new people and … found that [Facebook] a good way to keep in touch.’ Social media enabled participants to connect globally with other people who had similar interests, and positive interactions were built relatively easily using the functions of the platform: ‘I'm a “liker”, so, yeah that small little stuff like that builds, builds relationships, builds rapports’ (P11). However, connecting on social media with others did not necessarily involve actively engaging in communication per se (e.g., writing a written reply) or interaction (e.g., liking, sharing or retweeting). Over half the participants (n = 8) preferred to lurk: ‘I just watch other people's [posts], I don't really post much myself’ (P5); and valued watching from the sidelines: ‘I'm just observing the world’ (P12).

Customs and routines in posting

A majority (n = 11) of participants reported that they posted on social media every now and then: ‘I post a couple of things every little while, maybe once a week’ (P10, Facebook). Three participants also expressed themselves in different ways across the different social media platforms they used, for example: ‘I don't use really foul language like on Facebook or Instagram, but I do on Twitter’ (P10). Another participant did not like using hashtags in Instagram: ‘I mean I don't hashtag, I have no interest in hashtagging. I think that that is ugly for some reason’ (P11).

One participant had initially liked posting about her progress so that friends and family could see that she was improving. However, her use of social media was constantly changing, as P10 acknowledged: ‘yeah it's changed, it shifts a lot … once I realised there's parts that will never get better, it felt kind of worthless to post as much about it [recovery]’ (P10). Another participant (P7) posted a new blog entry talking about her brain injury twice per week. Most of her social media interactions were to share her blog content and connect with people who read and commented on the posts to provide encouragement and support.

All participants reported preferring to use one platform over another that they used (n = 13). Two who preferred to use online gaming explained that this was due to the interaction with others and increased challenge than found in solo computer games. However, P4 also said ‘gamers’ were ‘not very social … we don't talk about like “how was your day?” or anything like that’. Five participants reported using different social media platforms after their injury. For example, one participant (P13) had previously used Snapchat and Tumblr but had not since their TBI; and another participant once used Tumblr and Tinder but now used these platforms very little: ‘I use it once a year, I used to use it every day’ (P11). Overall, participants’ reports did not reflect major changes in their patterns of use over time, with only three reporting they had started to post and comment more frequently on a wider range of topics or with different people.

Personality and identity in social media

Across platforms, all participants enjoyed the agency and control that came with being ‘in charge of my accounts’ (P11) and exerting some control over their online persona. This occurred in the context of posting materials and responding to others, so was more pronounced for participants who used the platforms expressively. P9, who liked to be humorous and upbeat in persona, tailored her posts to include the realities of life. Her story reflected a sense of immediacy in sharing her experiences online to update her audience: ‘Straight after coming out of surgery … I grabbed my phone and took a picture [selfie] and I posted it to that group, “I made it out of surgery”, you know? With a peace sign.’ However, in repeatedly encountering negative or ‘troll’ attention, P9 had also become more willing to retaliate in social media, and she considered that social media had also made her ‘a meaner person’ (P9). Participants either persisted through the challenges of using social media expressively to establish a well‐developed online persona or maintained a low level of participation and used the platforms primarily to listen or observe others. While P11 was pleased to have some control over how she appeared online, for example, ‘I can un‐tag myself from photos or I can delete posts that I regret posting’, she was not impressed with the false facades that others presented on social media. Participants also reported that using social media had resulted in them being more self‐confident as they developed a sense of freedom of expression and through this a sense of belonging. Followers responding to their posts particularly encouraged them to share more online, and this led to a greater sense of participation and inclusion: ‘you get a sense of, “oh look, other people don't like this either”. You know, I'm not alone in this … we can all join together … so there's a, that belonging’ (P9).

An evolving sense of social media mastery

All participants felt they were ‘okay’ at using social media: ‘I mean I'm not good nor bad, I'm just, I know my way around it’ (P13). The four novice social media users in the group were at times confused, overwhelmed or lacked confidence in their own skills, and were more cautious when posting. They were nonetheless willing to explore and increase skills, as P4 said: ‘I probably don't actually know how to use it to be honest with you but I will say that I kind of figured it out’ but did not persist if the task was too time‐consuming or challenging. All had figured out, to varying degrees independently, how to use multiple social media platforms (n = 13): ‘I downloaded and worked them out on my own’ (P3), and through trial and error and persisting with repeated attempts: ‘I get there and that is all that matters’ (P2). They used internet search engines to seek answers to their questions about using social media (n = 5), and sought out models in the platforms to discover more about techniques: ‘[I] just looked at what other people did’ (P6). Six participants acknowledged that if they knew more about how to use the platforms, they might use social media more often. The established users in the group (n = 9) were confident and competent in more than one social media platform. Nonetheless, even established and frequent users reported lacking confidence in using or navigating platforms which were new to them; and novice users were satisfied enough to use multiple social media platforms daily (n = 4) and compared themselves favourably with people without TBI, as P1 said: ‘I feel like I'm on par with the rest of the world.’

As participants moved from one platform to the next, they moved back and forth from being a novice to an experienced user, developing skills through continued experiences and exposure, persisting through challenges, and building their skills and confidence. Over time, this movement from and return to being a novice expanded their overall competence and confidence in using social media. Their continued use of an expanding number of social media platforms was affected by their interactions over time, as well as their reasons for using social media. Learning to use the various platforms through trial and error, the participants’ manner and mastery of social media evolved, more rapidly if they used it as a form of expression. Over time, these users became more familiar with and adept at recognizing the challenges and implementing their own strategies for successful use of different social media platforms.

Discussion

People with TBI report they used social media to engage with friends and society more broadly, and through this develop a social identity. Their experiences are similar to those reported of other social media users (boyd 2014), and they have similar patterns of use to the general population (Pew Research Center 2016, Sensis 2017) and other people with TBI (Baker‐Sparr et al. 2018). They also report similar benefits to those previously reported by people without TBI (Sensis 2017), including the feeling of being closer and better connected to others, yet few of them used social media strategically for professional purposes or for advocacy and activism online. This finding reflects that people with TBI might not yet be included in disability advocacy or activist movements in social media (Trevisan 2017).

Staying connected and having a sense of belonging has also been linked with reconstruction of self‐identity after TBI (Douglas 2013), another theme highlighted in this study's results. As previously reported in the literature on social media and communication disability (Hemsley et al. 2018, Brunner et al. 2015, Paterson 2017), people with TBI in this study viewed social media favourably in fostering connections with people living near or far; as it gave them more time to respond; and enabled them to share their thoughts and feelings with a wider world. For them, social media worked to reduce isolation after TBI (Brunner et al. 2015, 2017). Like adults with cerebral palsy who used Twitter (Hemsley et al. 2015, 2018), the adults with TBI in this study had formed new relationships, with people that they had not yet met in real life. Their stories of improved self‐confidence through using social media support the notion that construction of self‐concept after TBI may be facilitated by a sense of connection between self and society, and having a place to create self‐narrative (Douglas 2013).

Cognitive impairments have previously been proposed as barriers to use of social media, associated with its poor universal access and the continual demands associated with constantly evolving social media sites (Baker‐Sparr et al. 2018, Brunner et al. 2015). In this study, challenges to using social media were not necessarily barriers to use per se but were nonetheless part of the terrain to be navigated. Most of the challenges in using social media related to communication demands, emotional reactivity (e.g., anxiety, feeling overwhelmed), and cognitive fatigue. The findings suggest that adults with TBI lack support in dealing with these challenges, and just as they had taught themselves through trial and error to use social media, they needed to find and instigate their own strategies to cope with feeling fatigued or overwhelmed. Those who persisted developed some resilience in managing some of the difficulties and also developed an evolving sense of social media mastery.

The full range of personalities and behaviours encountered in social media is an important consideration in relation to people with TBI, who are more vulnerable to mental health conditions (Lukow et al. 2015). The majority of participants in this study had heard about cyberbullying, and one third had been a target of cyber‐victimization. The finding that one participant considered that her social media defences made her ‘a meaner person’ suggests the possibility of an association between the development of cyber‐resilience (ASIC 2015, Jenaro et al. 2018) and the impact of social media on personality development (Suler 2004). In this study, the proportion of adults with TBI who reported they had been bullied online (31%) is relatively high (Sensis 2017, Pew Research Center 2017), adding weight to the suggestion that people with TBI may be more vulnerable to cyberbullying and online scams (Baker‐Sparr et al. 2018, Brunner et al. 2015, Jenaro et al. 2018). While participants with TBI who had experienced negative interactions online continued to use social media, some were cautious about what they posted and with whom they interacted; and valued having control over their online personae. The participants’ stories reflected a movement back and forth between being novice and experienced users across different social media platforms. Supporting previous research examining interactions with digital tools over time (Wakefield and Wakefield 2016), adults with TBI with more experience and exposure reported greater skill across more platforms, as well as active interest in pursuing answers to their questions when learning to navigate new platforms.

The results of this research have implications for ways to support adults with TBI in developing cyber‐resilience. People with TBI have lower levels of resilience compared with the general population (Kreutzer et al. 2016, Lukow et al. 2015). Where risk factors increase a person's vulnerability to negative events, resilience factors such as self‐determination, self‐efficacy, and dynamism can increase a person with TBI's ability to adapt and thrive after their injury (Dumont et al. 2004, Neils‐Strunjas et al. 2017, Lukow et al. 2015). All but one of the adults with TBI had returned to using their usual social media platforms post‐injury, and most had also taken up use of newer platforms. It is not known whether they returned to their same social networks even if they returned to the platforms. Some appreciated the sense of security and camaraderie they found through new social networks amid other people with TBI who understood their situation and with whom they felt safe. They reported using a wide array of strategies to navigate several challenges outlined, and exhibited cyber‐resilience in returning repeatedly to the challenges of using social media in the face of encountering cyberbullying. Further research is needed to determine how far using social media might support growth in the personal agency and control of adults with TBI and the development of resilience, particularly cyber‐resilience.

Social media in the context of rehabilitation after TBI

As in the use of gaming and virtual reality in rehabilitation after TBI (Tatla et al. 2014), there are several factors which influence adults with TBI in their use of social media. The results of this study, in relation to what keeps people with TBI using social media, suggest that some degree of mastery motivation (Morgan et al. 1990) might be important if it is to be used successfully in TBI rehabilitation. The individual's needs and abilities, as well as the communication technologies involved, were critical factors that affect outcomes in using social media for people after TBI (Brunner et al. 2017). Direct management of contextual factors contributes to positive long‐term functional outcomes (Ciccia and Threats 2015) and should be considered when digital tools are used in rehabilitation (Brunner et al. 2017). This is particularly important as social media use by people with TBI changes as their needs and abilities change (Brunner et al. 2017, Paterson 2017). Therefore, regular review of skills is important to address the several challenges encountered (e.g., as new platforms are developed) to maintain successful use and participation in online social communities (Brunner et al. 2017). To do so, it is imperative for clinicians to listen to patients’ preferences and values throughout their recovery to inform the development of rehabilitation programs after TBI that are relevant, meaningful and assist social participation (Cicerone 2004).

The model developed in this study (figure 1) reflects the evolution of mastery in participants’ social media skills and abilities. Although competence refers to an individual's capability, mastery includes the process and effort involved in developing those skills (Morgan et al. 1990). The process of developing social media mastery for adults with TBI depended on many factors: their initial motivators, ongoing drivers for use, short‐ and long‐term supports, their positive and negative experiences, and the diverse range of platforms that they had used. All of these factors could be explored in any TBI rehabilitation focusing on increased social participation in networked communities online. This study provides us with initial insight into ‘mastery motivation’ (Morgan et al. 1990) or drive for people with TBI to use social media alongside their family, friends and the wider world. In‐depth understanding of the factors that influenced social media mastery illustrated in figure 1 could inform both (1) the design of interventions to improve use of social media by people with TBI for communication; and (2) ways to make use of the skills demonstrated by adults with TBI who have mastered social media.

As observed in social media use by people who use AAC (Paterson 2017), some adults with TBI in this study, particularly those with more pronounced cognitive‐communication disability, found certain social media platforms easier to use and navigate so had a restricted range in their platforms used. Of note, adults with TBI in this study did not tend to interact with organizations or health professionals online, a finding also reflected in a study of tweets posted by adults with TBI (Brunner et al. 2018). This suggests that despite its global reach and immediacy in communication, social media is underutilized as a means of communicating about TBI and that TBI organizations could do more to engage with adults with TBI using these platforms (Brunner et al. 2018).

Limitations and directions for future research

This research adds qualitative understandings to the previous research of descriptive statistics on social media use after TBI (Baker‐Sparr et al. 2018), but the results cannot be taken to reflect the experiences of all adults with TBI who use social media and should be interpreted with caution. Recruitment through social media and e‐mail increased the feasibility of the study in locating adults with TBI who could inform its aims, but may have meant that some adults with TBI who use social media infrequently or presently lack access to the internet were not able to take part. The diverse group of participants with TBI who were interviewed did not allow any qualitative exploration of any differences of experience potentially relating to their age or site of injury. Nonetheless, the voices of adults with TBI captured in these interviews are a valuable resource for TBI rehabilitation professionals and organizations (Laukka et al. 2017)—particularly the voices of adults with TBI who prefer to lurk in social media, as it is not possible to determine very much about their social media experience by any other means (e.g., an analysis of their social media data posts).

Further social media research including people with TBI and cognitive‐communication disability is warranted to verify and expand upon the results of this study, through: (1) exploring the content of social media posts made by people with TBI; (2) measuring the social networks of people with TBI in terms of their size and density (Hemsley et al. 2018); and (3) examining potential reasons for changes in these networks over time. This information would help to inform the design of TBI rehabilitation programs that include a focus on social media participation. With growing expectations that technology and social media be incorporated into rehabilitation services (Brunner et al. 2017), a person‐centred approach in TBI services will be needed to support the use of social media. The fact that participants sought out help from individuals in situ on the same social media platform they were using shows the value of an immediacy to the response and proximity of the response to help, and in help being provided by someone using the same platform and in the user's network. The generosity of strangers on social media users is often noted (Suler 2004) and is one feature that drives both crowdsourcing volunteerism and advocacy online (Trevisan 2017).

This study revealed people with TBI being cyberbullied or trolled, or themselves responding to others harshly. As such, it would also be important to understand more about the nature of any relationship between resilience following TBI and the development of cyber‐resilience in social media. Considering the challenges encountered by adults with TBI in this study, their increased vulnerability to mental health conditions, and their stories of supports from family, friends, and acquaintances, it is also important that future research explore the roles of rehabilitation professionals and support staff working with adults with TBI on their use of social media. It is not known whether TBI rehabilitation professionals joining the social media networks of adults with TBI might be helpful in delivering ‘just‐in‐time’ supports at times when challenges are encountered, or whether such supports are better delivered by peers in the network. Understanding more about what would help these adults move more confidently through the steps and stages of social media use, depicted in figure 1 and described in the content themes in this study, might also help to guide therapists in the design of rehabilitation goals targeting transitions towards social media mastery and also develop the talents of people with TBI who are potential social media leaders.

Conclusions

Adults with TBI use social media to form and maintain connections with friends, family and strangers all over the world. However, many tend to lurk and observe others, and most lacked direct support on using the platforms and used a trial‐and‐error approach to developing their skills. All the participants described experiencing fatigue and some felt confused when using social media platforms. The patterns and purposes of use of social media suggest that social media provides a forum for practising communication skills regularly and this might be important as adults with TBI progress through rehabilitation, particularly in re‐developing a sense of self in returning to their social networks. However, it is likely that people with TBI will require training and support that is delivered promptly and is personally relevant in order to develop social media mastery. TBI rehabilitation professionals could consider the affordances of using social media with adults with TBI during their rehabilitation so as to assist people with TBI to navigate online communities safely and meaningfully.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and thank the research participants for contributing their time to be interviewed for this study; and the University of Newcastle for the administration of funding and support in the conduction of this study. Declaration of interest: This research was funded through an Australian Government Research Training Program scholarship to the first author and a Discovery Early Career Research Award from the Australian Research Council (last author). The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

Appendix A. Interview topic guide

Questions about current use of social media

Can you tell me more about what social media sites you use? (Circle relevant): Twitter / Facebook / Blogs / Instagram / LinkedIn / Tumblr / Other (describe):

How often do you use each one? (Circle relevant): many times per day / daily / a few times a week / weekly / a few times a month / monthly / less than monthly

How did you get interested in using (site name)?

Who do you link with through social networking? (in general, or specifically)

How did you learn how to use it?

What is it you like about social media?

Would you like to do more using social media?

Tell me what stops you from doing more?

Do you feel like you are good at using Social Media?

Do you have any ‘golden rules’ for your own use of the Internet / Social Media? (describe)

I guess you've heard that some people can get bullied or picked on, over the Internet. Do you know of it happening to anyone you know?

About being bullied or picked on, over the Internet, Is that something that you think could ever happen to you? What would you do if it happened to you?

End‐of‐interview questions

Is there anything else you'd like to add about how you use Twitter or other Social Media?

Is there anything you want to ask me?

[The copyright line for this article was changed on 5th September after original online publication.]

References

- Australian Securities And Investments Commission (ASIC) , 2015, Report 429, Cyber‐Resilience Health Check (ASIC) (Sydney, Australia: ). (available at: http://asic.gov.au/regulatory-resources/find-a-document/reports/rep-429-cyber-resilience-health-check/) (accessed on 5 May 2018). [Google Scholar]

- Baker‐Sparr, C. , Hart, T. , Bergquist, T. , Bogner, J. , Dreer, L. , Juengst, S. , Mellick, D. , O'neil‐Pirozzi, T. , Sander, A. and Whiteneck, G. , 2018, Internet and social media use after traumatic brain injury: a traumatic brain injury model systems study. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 33, E9–E17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- boyd, d. , 2014, It's Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens (New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press; ). [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V. , 2006, Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner, M. , Hemsley, B. , Dann, S. , Togher, L. and Palmer, S. , 2018, Hashtag #TBI: a content and network data analysis of tweets about traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 32, 49–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner, M. , Hemsley, B. , Palmer, S. , Dann, S. and Togher, L. , 2015, Review of the literature on the use of social media by people with traumatic brain injury (TBI). Disability and Rehabilitation, 37, 1511–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner, M. , Hemsley, B. , Togher, L. and Palmer, S. , 2017, Technology and its role in rehabilitation for people with cognitive‐communication disability following a traumatic brain injury (TBI). Brain Injury, 31, 1028–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccia, A. and Threats, T. , 2015, Role of contextual factors in the rehabilitation of adolescent survivors of traumatic brain injury: emerging concepts identified through modified narrative review. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 50, 436–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicerone, K. , 2004, Participation as an outcome of traumatic brain injury rehabilitation. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 19, 494–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, C. , Lê, K. , Mozeiko, J. , Hamilton, M. , Tyler, E. , Krueger, F. and Grafman, J. , 2013, Characterizing discourse deficits following penetrating head injury: a preliminary model. American Journal of Speech–Language Pathology, 22, S438–S448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. , 2014, Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (London: Sage; ). [Google Scholar]

- De Leeuw, E. , Hox, J. and Dillman, D. , 2008, International Handbook of Survey Methodology (New York, NY: Taylor & Francis; ). [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, J. , 2013, Conceptualizing self and maintaining social connection following severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 27, 60–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont, C. , Gervais, M. , Fougeyrollas, P. and Bertrand, R. , 2004, Toward an explanatory model of social participation for adults with traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 19, 431–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S. and Kyngäs, H. , 2008, The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62, 107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemsley, B. , Dann, S. , Palmer, S. , Allan, M. and Balandin, S. , 2015, ‘We definitely need an audience’: experiences of Twitter, Twitter networks and tweet content in adults with severe communication disabilities who use augmentative and alternative communication (AAC). Disability and Rehabilitation, 37, 1531–1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemsley, B. , Palmer, S. and Balandin, S. , 2014, Tweet reach: a research protocol for using Twitter to increase information exchange in people with communication disabilities. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 17, 84–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemsley, B. , Palmer, S. , Dann, S. and Balandin, S. , 2018, Using Twitter to access the human right of communication for people who use augmentative and alternative communication (AAC). International Journal of Speech–Language Pathology, 20, 50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemsley, B. , Palmer, S. , Goonan, W. and Dann, S. , 2017, Motor neurone disease (MND) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): social media communication on selected #MND and #ALS tagged tweets. Paper presented at the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2017, pp. 41–47 (available at: http://ebooks.iospress.nl/volumearticle/44287).

- Jenaro, C. , Flores, N. and Frías, C. , 2018, Systematic review of empirical studies on cyberbullying in adults: what we know and what we should investigate. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 38, 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzer, J. , Marwitz, J. , Sima, A. , Bergquist, T. , Johnson‐Greene, D. , Felix, E. , Whiteneck, G. and Dreer, L. , 2016, Resilience following traumatic brain injury: a traumatic brain injury model systems study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 97, 708–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laukka, E. , Rantakokko, P. and Suhonen, M. , 2017, Consumer‐led health‐related online sources and their impact on consumers: an integrative review of the literature. Health Informatics Journal. 10.1177/1460458217704254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukow, H. , Godwin, E. , Marwitz, J. , Mills, A. , Hsu, N. and Kreutzer, J. , 2015, Relationship between resilience, adjustment, and psychological functioning after traumatic brain injury: a preliminary report. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 30, 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, G. , Harmon, R. and Maslin‐Cole, C. , 1990, Mastery motivation: definition and measurement. Early Education and Development, 1, 318–339. [Google Scholar]

- Neils‐Strunjas, J. , Paul, D. , Clark, A. , Mudar, R. , Duff, M. , Waldron‐Perrine, B. and Bechtold, K. , 2017, Role of resilience in the rehabilitation of adults with acquired brain injury. Brain Injury, 31, 131–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberst, U. , Wegmann, E. , Stodt, B. , Brand, M. and Chamarro, A. , 2017, Negative consequences from heavy social networking in adolescents: the mediating role of fear of missing out. Journal of Adolescence, 55, 51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson, H. , 2017, The use of social media by adults with acquired conditions who use AAC: current gaps and considerations in research. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 33, 23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M. , 2015, Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; ). [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center , 2016, Social Media Update 2016 (available at: http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/14/2016/11/10132827/PI_2016.11.11_Social-Media-Update_FINAL.pdf) (accessed on 14 January 2018).

- Pew Research Center , 2017, Online Harassment 2017 (available at: http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/14/2017/07/10151519/PI_2017.07.11_Online-Harassment_FINAL.pdf) (accessed on 14 January 2018).

- Riessman, C. , 2008, Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; ). [Google Scholar]

- Sacco, R. , Kasner, S. , Broderick, J. , Caplan, L. , Culebras, A. , Elkind, M. , George, M. , Hamdan, A. , Higashida, R. and Hoh, B. , 2013, An updated definition of stroke for the 21st century. Stroke, 44, 2064–2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sensis , 2017, Australians and social media. In Sensis Social Media Report 2017, ch. 1 (available at: http://www.sensis.com.au/socialmediareport) (accessed on 15 June 2017).

- Sim, P. , Power, E. and Togher, L. , 2013, Describing conversations between individuals with traumatic brain injury (TBI) and communication partners following communication partner training: using exchange structure analysis. Brain Injury, 27(6), 717–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suler, J. , 2004, The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychology and Behavior, 7, 321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate, R. , 1999, Executive dysfunction and characterological changes after traumatic brain injury: two sides of the same coin? Cortex, 35, 39–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatla, S. , Sauve, K. , Jarus, T. , Virji‐Babul, N. and Holsti, L. , 2014, The effects of motivating interventions on rehabilitation outcomes in children and youth with acquired brain injuries: a systematic review. Brain Injury, 28, 1022–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, S. , 2013, Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact (Chichester: Wiley; ). [Google Scholar]

- Trevisan, F. , 2017, Crowd‐sourced advocacy: promoting disability rights through online storytelling. Public Relations Inquiry, 6, 191–208. [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield, R. and Wakefield, K. , 2016, Social media network behavior: a study of user passion and affect. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 25, 140–156. [Google Scholar]