Abstract

Background

Breastfeeding support is important for breastfeeding mothers; however, it is less clear how mothers of preterm infants (< 37 gestational weeks) experience breastfeeding support during the first year. Thus, the aim of this study was to describe how mothers of preterm infants in Sweden experience breastfeeding support during the first 12 months after birth.

Methods

This qualitative study used data from 151 mothers from questionnaires with open‐ended questions and telephone interviews. The data were analyzed using an inductive thematic network analysis with a hermeneutical approach.

Results

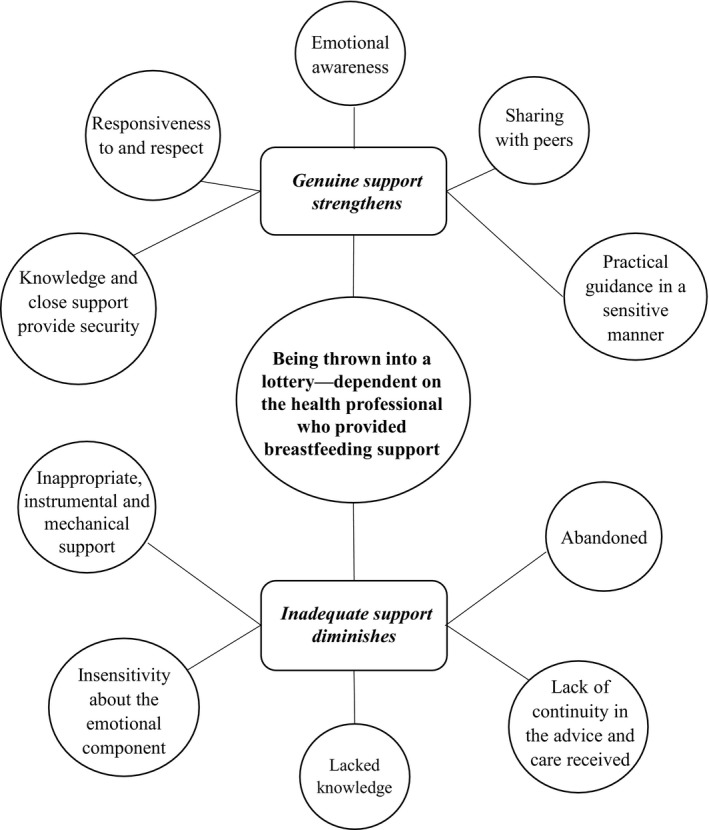

The results exposed two organizing themes and one global theme. In the organizing theme “genuine support strengthens,” the mothers described how they were strengthened by being listened to and met with respect, understanding, and knowledge. The support was individually adapted and included both practical and emotional support. In the organizing theme “inadequate support diminishes,” the mothers described how health professionals who were controlling and intrusive diminished them and how the support they needed was not provided or was inappropriate. Thus, the global theme “being thrown into a lottery—dependent on the health professional who provided breastfeeding support” emerged, meaning that the support received was random in terms of knowledge and support style, depending on the individual health professionals who were available.

Conclusion

Breastfeeding support to mothers of preterm infants was highly variable, either constructive or destructive depending on who provided support. This finding clearly shows major challenges for health care, which should make breastfeeding support more person‐centered, equal, and supportive in accordance with individual needs.

Keywords: breastfeeding support, child health care center, neonatal care, postnatal care, preterm infant

1. INTRODUCTION

Breastfeeding has beneficial effects, especially on the health, growth, and development of preterm infants (gestational age < 37 weeks).1, 2 The World Health Organization recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of postnatal age and, after that, partial breastfeeding for 2 years or longer.3 It has been suggested that even small changes in the prevalence of breastfeeding may result in significant societal health disparities for infants and mothers through changes in health, health care costs, and economic productivity.4

The time until a preterm infant can feed from the breast varies as a result of the immaturity of their breastfeeding behavior, and for some infants, breastfeeding difficulties may persist after discharge from the neonatal unit.5, 6 For mothers of preterm infants, breastfeeding may be perceived as both a positive bonding experience and/or a challenge because of immature infant breastfeeding behavior, breastmilk expression, and inadequate support.7

Many studies8, 9, 10, 11 have highlighted the importance of breastfeeding support for helping mothers of full‐term infants succeed in their breastfeeding goals. Adequate breastfeeding support should involve person‐centered supportive care, trusting relationships, and continuity of care.12 However, when support is not individualized, there is a risk that mothers will feel pressure and stress instead of support for breastfeeding.12 There is a lack of studies that focus on the experiences of mothers of preterm infants with breastfeeding support beyond their time in neonatal units and a few weeks after discharge. Earlier research showed that mothers are offered varying degrees of professional breastfeeding support in neonatal units and experience a lack of support and follow‐up counselling, especially concerning breastfeeding after discharge.13, 14

To develop breastfeeding support systems, it is important to understand the experiences of breastfeeding support in mothers of preterm infants during the first 12 months after birth. Therefore, the aim of this study was to describe how mothers of preterm infants experience breastfeeding support during the first 12 months of postnatal age.

2. METHODS

In this qualitative study, we followed mothers of preterm infants (gestational age < 37 weeks) to describe their experiences with breastfeeding support up to 12 months of postnatal age after discharge from neonatal units. The mothers in this study participated in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) that evaluated the effectiveness of proactive telephone support for breastfeeding after discharge from neonatal units, previously described by Ericson et al.15 The mothers’ experiences with breastfeeding support during the RCT are presented by Ericson et al.16 This study focused on how the mothers experienced breastfeeding support in general, irrespective of the group allocation or support provided during the RCT. The characteristics of the mothers who participated in this study are described in Table 1. The Regional Ethical Review Board, Uppsala, approved the study (Dnr: 2012/292 and 2012/292/2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of women in study of breastfeeding support for mothers of preterm infants, Sweden, 2013‐2015

| Participant characteristics, n = 151 | No. (%), mean ± SD or Median [IQR] |

|---|---|

| Maternal age, years | 30.3 ± 4.8 |

| Maternal educational level | |

| Higher education (university degree) | 90 (60) |

| Upper secondary school or less | 61 (40) |

| Primipara mothers | 91 (61) |

| Mothers not born in Sweden | 9 (6) |

| Vaginal birth | 81 (54) |

| Women with multiple births | 23 (15) |

| Infant gestational age at birth, weeks | 34 [2] |

| Infant gestational age at discharge, weeks | 38 [2] |

| Length of stay for the infant, days | 24 [22] |

| Exclusive breastfeeding | |

| At discharge | 123 (81) |

| 8 weeks after discharge | 91 (60) |

| 6 months of postnatal age | 43 (28) |

| Partial breastfeeding at 12 months of postnatal age | 33 (22) |

IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

In Sweden, mothers are offered breastfeeding support during their stays in neonatal units. After discharge, mothers can make regular visits to child health care centers, where breastfeeding support is part of the service. If additional support or care is needed, mothers are referred to other health care services or peer support.

2.1. Data collection

In total, 151 mothers provided data for this study: 125 left written comments, 12 were interviewed by telephone, and 14 were both interviewed and left written comments. Follow‐up questionnaires, which were a part of the RCT, were sent to the mothers 8 weeks after discharge from neonatal units and at 6 and 12 months after birth, between March 2013 and December 2015. The questionnaires included open‐ended questions that focused on infant feeding and breastfeeding support, as shown in Table 2. During March and April 2016, individual telephone interviews were conducted as a part of the RCT with mothers whose infants had been home for more than 2 months but less than 6 months. These mothers gave their consent to participate in a telephone interview about their experiences with breastfeeding and breastfeeding support via a letter attached to the questionnaires and were the first participants to respond to the call for interviews. The interviews were guided by a semi‐structured interview guide containing questions such as “Could you please tell me how you have experienced breastfeeding support?”

Table 2.

Open‐ended questions on the questionnaires administered to participating mothers of preterm infants 8 weeks after discharge and at 6 and 12 months after birth, Sweden, 2013‐2015

| Questions | Follow‐up time points | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response option | 8 weeks after discharge | 6 months after birth | 12 months after birth | |

| If you want, feel free to write what you have experienced while breastfeeding/bottle‐feeding your baby. | Open‐ended | x | x | x |

| How did you experience breastfeeding support | ||||

| In general? | Open‐ended | x | ||

| In the neonatal unit? | Open‐ended | x | ||

| In the maternity ward? | Open‐ended | x | ||

| At the child health care center? | Open‐ended | x | ||

x = the question was asked at this point.

The written answers were put together in a Microsoft Office Word document; the telephone interviews were audio‐recorded and transcribed verbatim, and they lasted for a mean of 15 minutes (range 7‐42 minutes).

2.2. Data analysis

The epistemological foundation of the study was hermeneutic philosophy,17, 18 and a thematic network analysis, inspired by Attride‐Stirling,19 was used to organize the data to interpret the findings. To accomplish this objective, the authors read the transcribed text from the telephone interviews and the written text several times. As a first step, segments of the text were identified and coded in accordance with the aim of the study. These segments of text were organized into basic themes (italics in the text). The authors interpreted the basic themes into organizing themes, which are abstract and more revealing of the mothers’ experiences. Finally, the organizing themes were interpreted into a global theme that encompasses the data as a whole. In this study, the global theme was described as a metaphor. The authors continued to critically reflect on all steps of the analytic process and on all analytical decisions until they reached a consensus. The quotes from the telephone interviews were labeled (interview xx), and quotes from the written comments were labeled with each mother's randomization code, eg, (SK43).

3. RESULTS

The mothers’ narratives about breastfeeding support during the first 12 months after birth were expressed in two organizing themes: “Genuine support strengthens” and “Inadequate support diminishes.” A global theme emerged from these two organizing themes: “Being thrown into a lottery—dependent on the health professional who provided breastfeeding support” (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework in study of breastfeeding support for mothers of preterm infants, Sweden, 2013‐2015

3.1. Genuine support strengthens the mothers

Genuine support occurred when support was provided in a space that was individually adapted and in which breastfeeding was considered an important activity and part of life. Genuine support was experienced by mothers as strengthening through supportive encounters, which meant being met with responsiveness to and respect for the mothers’ unique needs. The mothers expressed the importance of the health professionals being sensitive to and engaged in their breastfeeding situations. Having power and control over their breastfeeding situation was important for continuing breastfeeding and strengthening the mothers.

One of the nurses I truly liked came in and sat with me sometimes. She helped me, encouraged me, and noted that it was going well. That felt very good. She made me a little calmer.//It is also nice to hear that it will resolve, and it will be fine as well, getting a little comforted. (Interview 2)

Genuine support was experienced as supportive in the following situations: when the mothers received support that was individually adapted and had no demands (SK72); when the health professionals were calm (K25); and when breastfeeding truly got much of the focus, as per my wish (SK86). It was encouraging and strengthening when health professionals were able to provide hope and a sense of security for the future when breastfeeding was difficult and demanding (eg, when the mother faced challenges from immature infant breastfeeding behavior and milk supply concerns) or when someone who understood and/or wanted to understand the individual breastfeeding situations supported the mothers.

The staff [at the neonatal unit] prepped me to continue expressing breast milk, which was good; I believe that much support is needed at that stage, before the child learns to breastfeed, when it is hard and stressful. (F64)

Another aspect of genuine support was the importance of emotional awareness in a support situation, which gave the mothers an opportunity to tell their breastfeeding story.

I thought she [a nurse] was listening, and I did not think she judged.//She sat down, listened, understood and told me that it was OK to feel like this and I can do like this: ‘We [the staff] understand that it's hard for you to be here [in the neonatal unit].’ (Interview 4)

This emotional awareness involved genuine support that was visible in the environment and an atmosphere in which breastfeeding support was provided in a way that the mothers experienced as comfortable, peaceful and trustworthy, with the opportunity for privacy. One mother expressed that peace and quiet, much time and no stress (F101) were needed to facilitate breastfeeding.

The mothers described practical guidance in a sensitive manner as essential and helpful in breastfeeding support. Being provided with concrete and visible tips and ideas for proceeding with breastfeeding in an individual and respectful way was described as supportive. This practical guidance should preferably include information about different breastfeeding positions, infant positioning and behaviors, correct latching, and breastmilk expression.

A nurse showed how to make him wake up because he fell asleep all the time. You got support in what you should do to keep him awake and how to touch him to make him swallow. (Interview 2)

Furthermore, the mothers also wished to receive practical help during the first breastfeeding attempts in the neonatal unit, when all the wires, tubes, etc. are scary and difficult to handle (K54).

Knowledge and close support provide security, in that the mothers felt secure and appreciated when health professionals were knowledgeable about breastfeeding a preterm infant; this knowledge was sometimes lacking outside of the neonatal units.

We had been to a follow‐up at the hospital, and they had a completely different view of preterm infants than my child health care nurse; it felt like she [the nurse] was unfamiliar with preterm infants and did not truly know how to handle her [the infant] preterm birth, while the neonatal unit had super control. (Interview 21)

An example of close support was domiciliary care, ie, the infant could go home and for example, be tube‐fed by the parents, with support and follow‐up from the neonatal unit. Domiciliary care was offered at all neonatal units, and this care strengthened the mothers; it involved few health professionals and was an opportunity to meet each mother individually, both practically and emotionally. One mother stated that personal contact is worth its weight in gold (K93). Domiciliary care was also described as providing security because professional support was available when needed, and it gave the mothers a sense of trust in their ability to breastfeed their preterm infants. This security made the mothers feel relaxed and calm in difficult breastfeeding situations and helped them feel secure when returning home.

I received good help and encouragement from the domiciliary care, and it felt secure to know that help was close! (K12)

Sharing with peers, which could also involve online support, was another dimension of supportive breastfeeding encounters that strengthened the mothers. The opportunity to share experiences with individuals other than health professionals induced hope and communion. Such sharing was important for continued breastfeeding. In peer‐support situations, mothers can identify themselves, share their breastfeeding experiences and stories and, in a relaxed way, help each other understand breastfeeding and move forward.

I joined a Facebook group, which facilitated a lot. To have someone with the same experiences, or in a similar situation anyway. It's great to have others who understand, for those who only have one infant do not understand. (Interview 3)

3.2. Inadequate support diminishes the mothers

The mothers expected the health professionals to be experts on breastfeeding, and inadequate support overshadowed breastfeeding and gave the mothers the feeling that they were doing everything wrong.

Inadequate support included inappropriate, instrumental, and mechanical support, characterized by a lack of responsiveness and reciprocity. The mothers felt that they were being forced to do something or subject to the health professionals’ attitudes. Furthermore, the health professionals sometimes took over or exerted power in an insensitive manner.

It feels as if you must have their [the staff's] approval to do things. It would be slightly as if they're not my children, [like] I will borrow them a little. (Interview 3)

Such inadequate support could include statements indicating that the mother was doing something wrong or was not breastfeeding in a way that the individual health professional liked or found satisfactory, despite the fact that the mother was satisfied with the breastfeeding situation. In such situations, the mothers felt insecure and/or violated by the health professional.

Then, she told me how wrongly I held him when I was going to breastfeed, although everyone else said I did it right.//I could not hold him the way I did. That made me unsure. (F23)

In line with this theme, breastfeeding was perceived as only food for the infant, and the focus was mostly on milk production, the infant's weight gain or technical aspects of breastfeeding, which made the mothers feel pressured and/or forced them to stop breastfeeding. It is also possible that health professionals did not trust that breastfeeding was adequate nutrition for the infant, and consequently, in a nonreflecting manner, they prescribed formula as the gold standard and the only option for infant weight gain issues. This occurrence was primarily described at the child health care centers.

When I got home, it was almost more about that I had to start giving him formula and that he did not gain weight. I didn't truly get peace and quiet in breastfeeding. (Interview 7)

When health professionals lacked knowledge of or engagement in supporting breastfeeding, the mothers felt that the health professionals were unreliable and untrustworthy.

My child has Down syndrome, and given this fact, the health care professionals seem to assume that breastfeeding would not work. We asked for tips to start breastfeeding in the postnatal ward. As it was my firstborn, I was surprised that I did not get help with breastfeeding directly; I had to take the initiative myself. (SK78)

It was obvious that there was a gap in the knowledge of certain health professionals that resulted in confusion, which then decreased the mother's ability to trust herself.

At the child health care center, I have not received any help at all. They referred us to the neonatal unit because they knew more about preterm infants. (F90)

Inadequate support also resulted in a lack of continuity in the advice and care received. The mothers experienced a lack of cooperation among the health professionals and were torn between differing information and advice based on the professionals’ personal beliefs and opinions about breastfeeding. This situation left the mothers in an in‐between state.

At the neonatal unit, I got different advice all the time from different nurses and doctors. You want uniform advice; otherwise, you only get confused and insecure with yourself. (K 61)

Some mothers were left to themselves to determine how to breastfeed a preterm infant. During the stay at the neonatal unit, several mothers described feeling abandoned in the process of initiating breastfeeding since the health professionals failed to encourage breastfeeding and/or milk expression at an early stage.

I wanted to try to breastfeed my child earlier, but the staff thought it was too early. I did not dare to try because the staff constantly watched me with my child. (Ö21)

In addition, the mothers felt abandoned at the child health care center.

I thought I would get support from the child health care center; however, I did not get that. They just said I could search online. (Interview 6)

Inadequate support also included insensitivity about the emotional component of breastfeeding; in such situations, the mothers were left to handle their emotions themselves.

I would have needed slightly more support for the emotional part. You get help with the practical, but just for this emotional part, when you bond with the child, you have to manage yourself. (Interview 20)

3.3. Being thrown into a lottery––dependent on the health professional who provided breastfeeding support

The randomness of “being thrown into a lottery” referred to being subject to coincidence in terms of the type of breastfeeding support that mothers with preterm infants could receive, such as receiving genuine support, running the risk of receiving inadequate support, or both. The mothers were dependent on the individual health professionals and/or the traditions of the unit/child health care centers and the culture and history of giving breastfeeding support. Hence, breastfeeding support varied depending on which health professionals were working in terms of their knowledge, approach, and support style. When the support was highly variable, the mothers were forced to handle the different health professionals’ approaches. This could either strengthen or diminish the mothers in their breastfeeding situation.

4. DISCUSSION

This study aimed to describe the experiences that mothers of preterm infants had with breastfeeding support during the first 12 months after birth. Two organizing themes emerged in the analysis: “genuine support strengthens” and “inadequate support diminishes,” which give rise to one global theme: “being thrown into a lottery—dependent on the health professional who provided breastfeeding support.”

The global theme of being thrown into a lottery indicates a health care system that lacks the ability to provide genuine breastfeeding support for all mothers with preterm infants. For example, the health professionals’ lack of trust in breastfeeding, which often led to the prescription of formula as a solution for breastfeeding problems for mothers who wanted to breastfeed, may undermine the mothers’ ability to breastfed. This trend shows the medicalization of breastfeeding, as presented by Eden,20 which can be understood as a sociocultural process that is influenced by a medical focus on infant feeding and breastfeeding support. Furthermore, the attitudes of health professionals may affect the extent to which solution‐focused care was applied, for example, to give formula in a severe breastfeeding situation even though the mother wants to breastfeed.21 Another example of the lack of ability to provide genuine breastfeeding support was that some mothers were abandoned in their breastfeeding. An explanation may be insecurity and/or a lack of knowledge and skills on the part of the individual health professional to support breastfeeding; this explanation is supported in a study by Dykes.22 Furthermore, a fear of raising feelings of guilt, therefore avoiding the experience, may be another explanation.23 These findings demonstrate the need for a comprehensive national support system to make breastfeeding support more consistent and provide health professionals with guidance and knowledge to support breastfeeding. An example of such evidence‐based interventions is the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative, which was not being used in Sweden at this time.24, 25

This study shows results for and experiences of breastfeeding that were similar to those of earlier studies, which included mothers or settings with full‐term infants.9, 26 These are interesting results, not only in that mothers of full‐term and preterm infants describe similar experiences of breastfeeding support and support styles but also in that this study was performed in Sweden. Sweden has been regarded as a pro‐breastfeeding culture with high breastfeeding initiation rates. However, many mothers cease breastfeeding during the first several months in Sweden, and only 14.6% are exclusively breastfeeding at 6 months of postnatal age.27 This finding indicates that many mothers in Sweden do not receive the breastfeeding support they need to continue breastfeeding.

Both mothers and health professionals may face challenges with breastfeeding a preterm infant as a result of issues surrounding breastmilk expression, immature infant feeding behavior, and milk supply concerns.6, 7 In particular, nurses in child health care centers might not care for many preterm infants, and they therefore may lack knowledge of preterm infants’ feeding behavior, which may result in inadequate support. This finding is supported by a qualitative study from Canada, in which public health nurses found it difficult to guide mothers of preterm infants in breastfeeding.6 Our findings highlight the specific challenges health professionals face when supporting breastfeeding among mothers of preterm infants. Thus, our results suggest that health professionals need greater awareness and education about breastfeeding in preterm infants and providing genuine support for their mothers accordingly.

A main strength of this study was that it included rich descriptions of different mothers’ experiences, which provided a broad picture of the experiences of breastfeeding support in different health care settings over a long follow‐up period. Few studies have followed mothers of preterm infants during the first 12 months after birth. Another strength of this study was that it included data from several sources, ie, open‐ended questions and telephone interviews, which provided broad insight into a mother's experience. Study generalizability could have been affected in that mothers who provided data for this study also participated in an RCT of breastfeeding support. However, the data on the mothers’ experiences of the support given during the RCT were excluded from this study and are presented elsewhere.16 A limitation of this study was that it only included mothers who were breastfeeding at discharge; thus, the study lacked experiences from mothers who ceased breastfeeding during their stay in neonatal units, which may have provided important insights into the reasons for ceasing breastfeeding.

4.1. Conclusion

This study highlighted that mothers of preterm infants feel vulnerable, as they are dependent on each health professional's individual support style. This finding poses a challenge for health care to provide more even breastfeeding support based on mothers’ perspectives, which would allow mothers to breastfeed according to their own desires.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors express their deepest gratitude to the mothers who participated in the study.

Ericson J, Palmér L. Mothers of preterm infants’ experiences of breastfeeding support in the first 12 months after birth: A qualitative study. Birth. 2019;46:129–136. 10.1111/birt.12383

Funding information

This study was supported by the Centre for Clinical Research Dalarna and the Uppsala‐Örebro Regional Research Council, the Birth Foundation, and the Gillbergska Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1. Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJ, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475‐490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lechner BE, Vohr BR. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of preterm infants fed human milk: a systematic review. Clin Perinatol. 2017;44(1):69‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization (WHO) . Breastfeeding. 2017. http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/newborn/nutrition/breastfeeding/en/. Accessed September 18, 2017.

- 4. Renfrew MPS, Quigley M, McCormick F, et al. Preventing Disease and Saving Resources: The Potential Contribution of Increasing Breastfeeding Rates in the UK. London: UNICEF; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lau C. Development of suck and swallow mechanisms in infants. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66(Suppl 5):7‐14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dosani A, Hemraj J, Premji SS, et al. Breastfeeding the late preterm infant: experiences of mothers and perceptions of public health nurses. Int Breastfeed J. 2016;12:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kair LR, Flaherman VJ, Newby KA, Colaizy TT. The experience of breastfeeding the late preterm infant: a qualitative study. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10(2):102‐106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burns E, Schmied V, Sheehan A, Fenwick J. A meta‐ethnographic synthesis of women's experience of breastfeeding. Matern Child Nutr. 2010;6(3):201‐219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schmied V, Beake S, Sheehan A, McCourt C, Dykes F. Women's perceptions and experiences of breastfeeding support: a metasynthesis. Birth. 2011;38:49‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Demirtas B. Strategies to support breastfeeding: a review. Int Nurs Rev. 2012;59(4):474‐481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McFadden A, Gavine A, Renfrew MJ, et al. Support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schmied V, Beake S, Sheehan A, McCourt C, Dykes F. Women's perceptions and experiences of breastfeeding support: a metasynthesis. Birth. 2011;38(1):49‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Niela‐Vilen H, Axelin A, Melender HL, Salantera S. Aiming to be a breastfeeding mother in a neonatal intensive care unit and at home: a thematic analysis of peer‐support group discussion in social media. Matern Child Nutr. 2015;11(4):712‐726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Larsson C, Wagstrom U, Normann E, Thernstrom BY. Parents experiences of discharge readiness from a Swedish neonatal intensive care unit. Nurs Open. 2017;4(2):90‐95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ericson J, Eriksson M, Hellstrom‐Westas L, Hagberg L, Hoddinott P, Flacking R. The effectiveness of proactive telephone support provided to breastfeeding mothers of preterm infants: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ericson J, Flacking R, Udo C. Mothers’ experiences of a telephone based breastfeeding support intervention after discharge from neonatal intensive care units: a mixed‐method study. Int Breastfeed J. 2017;12:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gadamer H‐G, Weinsheimer J, Marshall DG. Truth and Method. London: Bloomsbury; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dahlberg K, Dahlberg H, Nyström M. Reflective Lifeworld Research, 2nd edn Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Attride‐Stirling J. Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual Res. 2001;1(3):385‐405. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smith PH, Hausman BL, Labbok MH. Beyond Health, Beyond Choice: Breastfeeding Constraints and Realities. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zwedberg S, Naeslund L. Different attitudes during breastfeeding consultations when infant formula was given: a phenomenographic approach. Int Breastfeed J. 2011;6(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dykes F. The education of health practitioners supporting breastfeeding women: time for critical reflection. Matern Child Nutr. 2006;2(4):204‐216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Labbok M. Exploration of guilt among mothers who do not breastfeed: the physician's role. J Hum Lact. 2008;24(1):80‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nyqvist KH, Haggkvist AP, Hansen MN, et al. Expansion of the baby‐friendly hospital initiative ten steps to successful breastfeeding into neonatal intensive care: expert group recommendations. J Hum Lact. 2013;29(3):300‐309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. The World Health Organization . Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative. 2018. http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/bfhi_trainingcourse/en/. Accessed January 17, 2018.

- 26. Burns E, Fenwick J, Sheehan A, Schmied V. Mining for liquid gold: midwifery language and practices associated with early breastfeeding support. Matern Child Nutr. 2013;9(1):57‐73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. The National Board of Health and Welfare . National statistics about breastfeeding in Sweden. 2015. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistik/statistikdatabas/graviditeter-forlossningarochnyfodda. Accessed May 17, 2018.