Abstract

Objectives

This population-based study aimed to determine age-standardised prevalence of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) across the lifespan using multiple case ascertainment sources.

Design

Point-prevalence epidemiological study in the Auckland Region of New Zealand (NZ).

Setting

Multiple case ascertainment sources including primary care centres, hospital services, neuromuscular disease registry, community-based organisations and self-referral were used to identify potentially eligible participants.

Participants

Adults (≥16 years, n=207, 87.7%) and children (<16 years, n=29, 12.3%) with a confirmed clinical or molecular diagnosis of CMT, hereditary sensory neuropathy, hereditary motor neuropathy or hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies who resided in the Auckland Region of NZ on 1 June 2016.

Primary outcome

Prevalence per 100 000 persons with 95% CIs by subtype, age and sex were calculated and standardised to the world population.

Results

Age-standardised point prevalence of all CMT cases was 15.7 per 100 000 (95% CI 11.6 to 21.0). Highest prevalence was identified in those aged 50–64 years 25.2 per 100 000 (95% CI 19.4 to 32.6). Males had a higher prevalence (16.6 per 100 000, 95% CI 10.9 to 25.2) than females (14.6 per 100 000, 95% CI 9.6 to 22.4). Prevalence of CMT1A was 6.9 per 100 000 (95% CI 5.6 to 8.4). The majority (93.2%) of cases were identified through medical records, with 6.8% of cases uniquely identified through community sources.

Conclusions

A small but significant proportion of people with CMT are not connected to healthcare services. Epidemiological studies using medical records alone to identify cases may risk underestimating prevalence. Further studies using population-based methods and reporting age-standardised prevalence are needed to improve global understanding of the epidemiology of CMT.

Keywords: registries, epidemiology, cmt, charcot-marie-tooth disease, hereditary neuropathy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The use of multiple sources of case ascertainment reduces potential influence of selection bias.

The inclusion of all age groups and those with either a clinical or molecular confirmation of diagnosis is important for public health planning.

Presentation of age-standardised prevalence enables comparison of prevalence across different countries, important in understanding the global burden and population trends.

Low rates of neurophysiology and molecular confirmation of diagnosis were observed, indicating difficulties with access or uptake of neurophysiology and genetic testing in New Zealand (NZ).

To respect patient privacy and adhere to data sharing policies in NZ, it was difficult to identify family relationships between individually identified patients across different organisations.

Introduction

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT) encompasses a group of genetically and phenotypically diverse disorders primarily characterised by demyelination of the nerves or degeneration of the axons.1 2 CMT is divided into mutation-specific subtypes, with all types of Mendelian inheritance patterns observed.3 CMT1 has been reported to be the most common type, accounting for between 37.6% and 84.0% of cases.4 Symptoms include weakness and wasting of the muscles (predominantly distally in the legs and arms), cavovarus foot deformity (high arched feet), chronic pain, muscle cramps, impaired balance and paraesthesia.5 Most symptoms become apparent after 5 years of age and adversely impact on the affected person’s physical/emotional functioning and quality of life.5 6

Accurate prevalence data are important to inform healthcare service planning and resourcing as well as to provide an indication of the scope of societal burden. However, a recent systematic review of epidemiological studies of CMT revealed extremely variable prevalence from 9.7 per 100 000 in Serbia to 82.3 per 100 000 in Norway.4 The reason for the substantially higher prevalence reported in Norway is unclear, but is likely to be due to different case ascertainment methods (use of medical records within a relatively small population sample of 300 000) and possible founder effects.7 Excluding the study in Norway as an outlier, average prevalence was 14.5 per 100 000.4 Published studies vary considerably in their methodological quality and methodologies, which makes comparisons challenging.4 Existing studies have depended heavily on medical records to identify cases and may have underestimated cases by excluding those who received a diagnosis outside of the study area or if the person was self-managing in the community.4 8 Additionally, there were no identified studies conducted in Asia-Pacific. A recent study conducted in Ireland, which did use multiple case ascertainment sources (including patient support organisations) was limited as prevalence was restricted to those >18 years of age.9 The current study aimed to determine subtype, age and sex-specific prevalence of CMT in Auckland, New Zealand (NZ), using both clinical and community-based sources of case ascertainment across the lifespan.

Patients and methods

Setting

The Auckland Region (figure 1) is the most populated area of NZ, with 33% of the population residing in the region (national population=4 242 048).10 The population denominator for the Auckland Region (1 415 550) was determined by 2013 NZ census data.10 The New Zealand National Health Service provides residents with healthcare for medical conditions not caused by an accident.

Figure 1.

Map of New Zealand showing location of Auckland Region in the North Island of New Zealand (shaded).

Identification of study population

This epidemiological study aimed to identify all adults and children with a confirmed clinical or molecular diagnosis of CMT, living in the Auckland Region of NZ on the point prevalence date of 1 June 2016. Cases were ascertained using multiple overlapping sources. Keyword diagnostic searches and International Classification of Disease code (G60.0.356.1) were used to search neurologists’ patient lists (private and publicly funded services), hospital admission and discharge records, genetic services database and the national health database. Keyword searches were used to identify cases from the NZ Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA-NZ) membership database, and NZ Neuromuscular Disease Registry.11 Local health professionals including podiatrists, orthotics clinics, physiotherapists, speech and language therapists and general practitioners within the Auckland region of NZ were contacted to invite their patients into the study, as well as circulating leaflets for display in healthcare clinics. Additionally, national and regional disability services and culturally specific patient support organisations were asked to contact clients with the included conditions to inform them about the study and invite them to participate. Local media coverage (including newspaper advertisements and a Facebook page) were used to encourage self-referrals into the study. A freephone number was set up to facilitate direct contact with the study team. Interpreters were provided if required to facilitate participation in the study.

Searches of healthcare records were conducted by a member of staff employed by each participating organisation to protect patient confidentiality. Only demographic information (including sex, ethnicity and region of residence) and details of diagnosis were obtained for each new case (no names and addresses were required). In NZ, all citizens are routinely allocated a unique patient identification number enabling duplicate identification of cases from across multiple databases without the need for patient identifiers. Following completion of case ascertainment, National Health Index (NHI) numbers were removed from the main study database and kept in a separate password-protected file to protect patient confidentiality and data security.

Following identification, participants were contacted by the staff member at each organisation via phone, email or letter to provide them with brief information about the study. Participants interested in finding out more about the study were asked for their permission to share their contact details with the research team or to contact the research team directly. Written informed consent was obtained by the research team and further details about the person were collected. For participants who were not able to be contacted and those who did not wish to take part further, only the anonymised data on sex, ethnicity, region of residence and diagnosis were used.

Verification of diagnosis was obtained for all potentially eligible cases based on the NHI number from medical records, and clinical investigations which were provided with name and address details ‘blanked out’. Where there was supportive neurophysiology, we specified the subtype as type 1 demyelinating, type 2 (axonal) or intermediate. Any molecular confirmation of diagnosis was obtained from the NZ Genetics Service. For participants who had not had neurophysiological or genetic testing themselves, but who had a first-degree or second-degree relatives with a confirmed diagnosis, it was assumed that they had the same subtype. The study neurologists reviewed any cases where diagnosis was unclear. If there was insufficient evidence to verify a clinical diagnosis, the case was excluded.

All identified cases were checked against the national death registry to confirm living status on the point prevalence date.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved directly in the study design or analysis. The study was conducted in partnership with the MDA-NZ who represented the views of people living with CMT and their preferences. The findings of the study were mailed/emailed directly to participants following completion of the study. A summary of the results was also disseminated to participants through the study Facebook page, MDA-NZ patient newsletter and member meetings.

Statistical analysis

Population demographics including age, sex and ethnicity of the Auckland region were extracted from the 2013 census and used as the population denominator.10 Direct standardisation was used to age-standardise the rates to the world population for international comparability.12 Prevalence by age, sex and diagnostic subtype was calculated per 100 000 population with 95% CIs using the Poisson distribution.

Results

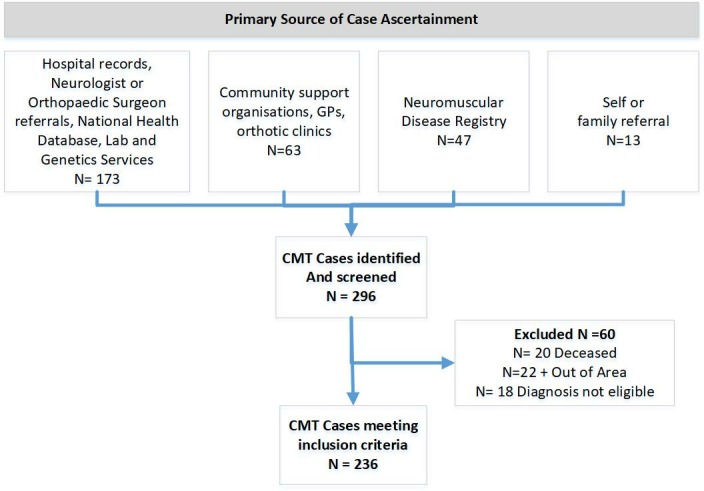

A total of 296 potentially eligible participants were identified and screened, 60 were deemed ineligible (figure 2). Two hundred thirty-six adults (≥16 years, n=207, 87.7%) and children (<16 years, n=29, 12.3%) met the inclusion criteria. Participants were aged between 3 months and 94 years of age (mean age on point prevalence date of 43.4, SD 22.7). Mean age at diagnosis was 34.1 (SD 22.1). Half of the sample were males (n=119, 50.4%), with the majority (n=170, 72.0%) being of NZ European ethnicity. Of the 236 eligible participants, the majority (93.2%) of the sample were identified by healthcare services (neurologist, hospital, genetics and health laboratories), 6.8% of participants were not known to healthcare services and were uniquely identified through the NZ Neuromuscular Disease Registry or through community services and family/self-referrals (figure 3). Over half of participants (n=139, 58.9%) indicated that at least one other family member was also affected by CMT. There were 48 participants with one other known affected member, 17 with 2 and 18 participants indicated there were 3–5 members of their family diagnosed with CMT, most of whom had also been captured within the study.

Figure 2.

Participant flow diagram. CMT, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease; GP, general practitioner.

Figure 3.

Multiple case ascertainment by all source types. NZ, New Zealand.

The overall crude point prevalence in Auckland, NZ on the point prevalence date was 16.7 per 100 000 (95% CI 14.6 to 19.0). After age adjustment according to the world standard population (to account for international population differences), prevalence of CMT was 15.7 per 100 000 (95% CI 11.6 to 21.0). This translates to one in every 6369 people in the Auckland Region of NZ with CMT. As expected CMT1A was the most common subtype (40.9% of cases) with a prevalence of 6.9 per 100 000 (95% CI 5.6 to 8.4) as shown in table 1. Of the 146 (61.1%) participants who had received a genetic test, the test provided molecular confirmation of diagnosis for 99 (41.9%) people. Of the 138 people who did not receive a molecular confirmation of diagnosis following a genetic test or who received an unconfirmed result, 79 (57.2%) had received a neurophysiology test.

Table 1.

Prevalence of CMT subtypes

| CMT subtype | N | Prevalence per 100 000 | 95% CI |

| CMT1A (PMP22 dup) | 97 | 6.9 | 5.6 to 8.4 |

| HNPP (PMP22del) | 18 | 1.3 | 0.8 to 2.1 |

| CMT1B (MPZ) | 2 | 0.1 | 0.0 to 0.6 |

| CMT1 (other)* | 17 | 1.2 | 0.7 to 2.0 |

| CMT2A (mitofusion 2) | 2 | 0.1 | 0.0 to 0.6 |

| CMT2C (TRPV4) | 1 | 0.1 | 0 to 0.5 |

| CMT2M (Dynamin 2) | 1 | 0.1 | 0 to 0.5 |

| CMT2 (other)* | 30 | 2.1 | 1.5 to 3.1 |

| CMTX1 (GJB1) | 5 | 0.4 | 0.1 to 0.9 |

| CMTX3 | 1 | 0.1 | 0 to 0.5 |

| CMTX (other)† | 6 | 0.4 | 0.2 to 1.0 |

| HMN | 2 | 0.1 | 0.0 to 0.6 |

| HSN (HSAN1) | 1 | 0.1 | 0 to 0.5 |

| Unclassified | 53 | 3.7 | 2.8 to 4.9 |

| Total | 236 | 16.7 | 14.6 to 19.0 |

*Cases classified based on nerve conduction study results.

†Based on family history and clinical presentation.

CMT, Charcot-Marie-Tooth.

As shown in table 2, age-standardised prevalence was slightly higher in males (16.6 per 100 000, 95% CI 10.9 to 25.2) than females (14.6 per 100 000, 95% CI 9.6 to 22.4). Highest prevalence (25.2 per 100 000, 95% CI 19.4 to 32.6) was observed in those aged 50–64 years. There were surprisingly few young females under the age of 15 years. Prevalence for those were aged 16 years or over was 18.7 per 100 000 (95% CI 15.4 to 22.6).

Table 2.

Prevalence of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease by age and sex

| Total population (n) | Number of cases (%) | Prevalence per 100 000 | 95% CI | |

| Boys and men | ||||

| 0–14 years | 151 839 | 19 (16.0) | 12.5 | (7.8 to 20.0) |

| 15–34 years | 200 958 | 32 (26.9) | 15.9 | (11.1 to 22.8) |

| 35–49 years | 143 652 | 19 (16.0) | 13.2 | (8.2 to 21.1) |

| 50–64 years | 116 796 | 29 (24.4) | 24.8 | (16.9 to 36.2) |

| ≥65 years | 74 244 | 20 (16.8) | 26.9 | (16.9 to 42.4) |

| Total | 687 492 | 119 (100.0) | 17.3 | (14.4 to 20.8) |

| Standardised | – | – | 16.6 | (10.9 to 25.2) |

| Girls and women | ||||

| 0–14 years | 144 516 | 8 (6.8) | 5.5 | (2.6 to 11.4) |

| 15–34 years | 208 659 | 27 (23.1) | 12.9 | (8.7 to 19.1) |

| 35–49 years | 160 485 | 29 (24.8) | 18.1 | (12.3 to 26.3) |

| 50–64 years | 125 284 | 32 (27.4) | 25.5 | (17.8 to 36.5) |

| ≥65 years | 88 905 | 21 (18.0) | 23.6 | (15.0 to 36.8) |

| Total | 728 058 | 117 (100.0) | 16.1 | (13.4 to 19.3) |

| Standardised | – | – | 14.6 | (9.6 to 22.4) |

| Total sample | ||||

| 0–14 years | 296 358 | 27 (11.4) | 9.1 | (6.1 to 13.5) |

| 15–34 years | 409 620 | 59 (25.0) | 14.4 | (11.1 to 18.1) |

| 35–49 years | 304 134 | 48 (20.3) | 15.8 | (11.8 to 21.1) |

| 50–64 years | 242 280 | 61 (25.9) | 25.2 | (19.4 to 32.6) |

| ≥65 years | 163 152 | 41 (17.4) | 25.1 | (18.3 to 34.4) |

| Total | 1 415 550 | 236 (100.0) | 16.7 | (14.6 to 19.0) |

| Standardised* | – | – | 15.6 | (11.6 to 21.0) |

*Standardised to the WHO standard population.

As shown in table 3, nearly half of all cases had a demyelinating CMT phenotype. While a higher proportion of females had an axonal phenotype than males, this difference was not significant (χ2=0.85, p=0.36).

Table 3.

Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) phenotype by gender

| Males N (%) |

Females N (%) |

Total N (%) |

|

| Demyelinating (CMT1) | 55 (46.2) | 55 (46.6) | 110 (46.4) |

| Axonal (CMT2) | 16 (13.4) | 20 (17.1) | 36 (15.3) |

| Intermediate | 9 (7.6) | 4 (3.4) | 13 (5.5) |

| Unclassified | 39 (32.8) | 38 (32.2) | 77 (32.5) |

| Total | 119 (100.0) | 117 (100.0) | 236 (100.0) |

Discussion

This study using multiple case ascertainment sources and presenting age-standardised data reveals 15.7 per 100 000 people are affected by CMT in Auckland, the largest region of NZ. Community case ascertainment sources were critical to the accuracy of prevalence findings, with 6.8% of cases uniquely identified through the community or the national neuromuscular disease registry. In comparison to the only other study presenting age-standardised prevalence conducted in Serbia (8.2 per 100 000),8 the prevalence of CMT in NZ was higher. However, this study highlights that the CMT prevalence of 1 in 6369 identified is far lower than the frequently quoted ‘1 in 2500 people,13 (ie, 40 per 100 000) identified in one of the first epidemiological studies of CMT. The prevalence was also found to be lower than recent studies conducted in Europe.14 15 As found in previous studies, CMT1A was the most common form of CMT and proportions of Hereditary Neuropathy with Liability to Pressure Palsy (HNPP) were found to be equivalent between this study and previous literature.16 Of the CMT1A cases, 73.2% had received a genetic test confirming the duplication. However, CMT1X was not the second most common subtype as is usually found. This may be due to the larger proportion of people who were unclassified or categorised as CMT1Other in the current study.

Age-standardised prevalence is important to take country specific population differences (eg, an older or younger population) into account to ensure data are comparable. Our higher prevalence to Serbia is likely to reflect our inclusion of community-based sources of case ascertainment in addition to medical records. However, there may be some unique differences by country that need further investigation. One of the main challenges with previous research is that most studies have only reported crude prevalence which has been found to vary considerably.4 Further work is needed to determine if differences in prevalence are simply due to methodological issues or if there are actual differences in prevalence by country to inform healthcare planning.

Less than half (41.9%) of participants had received a molecular confirmation of diagnosis. While this is comparably lower than the rate of 60.4% reported by the Inherited Neuropathies Consortium Centres,16 this compares favourably with a study of adults in the Ireland which reported a genetic diagnosis rate of 30.5%.9 We were surprised at the low rates of neurophysiology in this population and the findings suggest that increased access and information for patients on genetic and neurophysiological testing is needed. While every attempt was made to check if participants had received a nerve conduction study (including contacting neurologists working in private practice), it is acknowledged that some nerve conduction studies may not have been accessible.

Raw frequencies of numbers of males and females revealed no gender differences, but when age-standardised prevalence was calculated (taking sex differences in the population denominator into account), prevalence was slightly higher in males (16.1 per 100 000) than females (14.5 per 100 000). This finding is comparable to that identified in the Serbian study.8 The higher prevalence of women with axonal CMT may be partly accounted for by CMTX1 cases among boys that can have an earlier onset or more severe disease, whereas there may be preserved nerve conduction values in CMTX1 females.

Given onset of CMT symptoms usually occurs in childhood and adolescence,17 the low prevalence observed in those aged 0–15 years was surprising, particularly given that the mean age of diagnosis was 34 years of age. There was particularly low prevalence in girls (5.5 per 100 000) compared with boys (12.2 per 100 000). The reasons for this gender disparity in infants and children is unclear, but is likely to reflect social biases in identification of early symptoms between girls and boys. In NZ, most cases of childhood CMT are diagnosed based on clinical review and family history. The low number of children identified may reflect the approach of the National Genetic Service, which does not support the genetic testing of asymptomatic children. The findings may also reflect that parents may perceive little benefit in seeking early medical review if the condition is known within the family or delays within the health system in arranging for diagnostic tests. The low number of child cases identified in this study highlights the need for earlier identification and testing of potentially affected children. Indeed, early diagnosis and best practice care have been identified as essential to achieving health improvements for children (and adults) living with rare diseases.18

The advent of gene panels has facilitated and will continue to facilitate the diagnosis of rare CMT subtypes. In our cohort, one individual was diagnosed with CMT2M (dynamin 2) and another with CMT2c (TRPV4). It is also worth noting that one patient was diagnosed with CMTX3, a rare subtype, not diagnosable on current gene panels, highlighting the importance of taking an extended family history. One case of Autosomal Recessive Spastic Ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay and one case of Giant Axonal Neuropathy were identified as part of the study but were excluded as they were deemed not to meet the inclusion criteria. However, this opens up debate as to the expanding phenotype of these genetic mutations.

While this study has provided the most comprehensive case ascertainment procedure conducted to date to determine CMT prevalence, it is still likely that some cases of CMT were missed. Consequently, prevalence may still be an underestimate, particularly given the low prevalence in children. Indeed, a recent study based on a neonatal genetic screening programme and found prevalence of the PMP22 deletion associated with HNPP to be as high as 58.9 per 100 000.19 This suggests that not all disease mutation carriers develop the disease at such an extent to be detected based on clinical diagnosis and highlight ascertainment tools employed strongly influence prevalence estimates.

Additionally, as only one region of NZ was included, it is unclear if the findings reflect the whole country. Further confidence in our observed prevalence of subtypes of CMT is reduced as not all participants received a genetic test or neurophysiology. To respect patient privacy and adhere to data sharing policies in NZ, it was difficult to identify family relationships between individually identified patients across different organisations. However, due to low numbers of known affected family members, many of whom were also captured by the study, there was no evidence of any clear founder effects.

Conclusion

Age-standardised point prevalence of all CMT cases was 15.7 per 100 000 with higher prevalence in males than females. A small proportion of cases were uniquely identified through community-based sources of case ascertainment.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AT was the Principal Investigator for the study. AT, RR, EM, GOG, JB, KJ and MR contributed to the design of the study and obtained the funding. AT and PP performed the statistical analyses. All authors were involved in the interpretation of data and the writing and critical revision of the manuscript. AT had the primary responsibility for the final content.

Funding: This study was funded by the Neuromuscular Research Foundation Trust and the Richdale Charitable Trust.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Northern B Regional Ethics Committee of NZ (reference: 16/NTB/38), Auckland University of Technology Ethics Committee (reference: 16/170) and Auckland District Health Board (reference: A+7294).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: We will endeavour to make de-identifiable data (from participants giving their consent for data to be shared) available to the scientific community, while retaining exclusive use until the publication of major outputs. Requests for access to de-identified data should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Collaborators: Additional Impact CMT Research Group Members; Dean Kilfoyle; Moneeta Pal; Scott Denton; Ronelle Baker, Braden Te Ao.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on the map(s) in this article do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. The map(s) are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Contributor Information

on behalf of the Impact CMT Research Group:

Moneeta Pal, Scott Denton, Ronelle Baker, and Braden TE Ao

Collaborators: on behalf of the Impact CMT Research Group

References

- 1. Hoyle JC, Isfort MC, Roggenbuck J, et al. . The genetics of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease: current trends and future implications for diagnosis and management. Appl Clin Genet 2015;8:235–43. 10.2147/TACG.S69969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Klein CJ, Duan X, Shy ME. Inherited neuropathies: clinical overview and update. Muscle Nerve 2013;48:604–22. 10.1002/mus.23775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Timmerman V, Strickland AV, Züchner S. Genetics of Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) Disease within the Frame of the Human Genome Project Success. Genes 2014;5:13–32. 10.3390/genes5010013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barreto LC, Oliveira FS, Nunes PS, et al. . Epidemiologic Study of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease: a systematic review. Neuroepidemiology 2016;46:157–65. 10.1159/000443706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Redmond AC, Burns J, Ouvrier RA. Factors that influence health-related quality of life in Australian adults with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Neuromuscul Disord 2008;18:619–25. 10.1016/j.nmd.2008.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burns J, Ryan MM, Ouvrier RA. Quality of life in children with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. J Child Neurol 2010;25:343–7. 10.1177/0883073809339877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Braathen GJ, Sand JC, Lobato A, et al. . Genetic epidemiology of Charcot-Marie-Tooth in the general population. Eur J Neurol 2011;18:39–48. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03037.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mladenovic J, Milic Rasic V, Keckarevic Markovic M, et al. . Epidemiology of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease in the population of Belgrade, Serbia. Neuroepidemiology 2011;36:177–82. 10.1159/000327029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lefter S, Hardiman O, Ryan AM. A population-based epidemiologic study of adult neuromuscular disease in the Republic of Ireland. Neurology 2017;88:304–13. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Statistics New Zealand 2013 census. 2016. http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census.aspx.

- 11. Rodrigues M, Hammond-Tooke G, Kidd A, et al. . The New Zealand Neuromuscular Disease Registry. J Clin Neurosci 2012;19:1749–50. 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ahmad O, Boschi-Pinto C. Age Standardization of Rates: a new WHO Standard. GPE Discussion Paper Series: no31. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Skre H. Genetic and clinical aspects of Charcot-Marie-Tooth’s disease. Clin Genet 1974;6:98–118. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1974.tb00638.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lousa M, Vázquez-Huarte-Mendicoa C, Gutiérrez AJ, et al. . Genetic epidemiology, demographic, and clinical characteristics of Charcot-Marie-tooth disease in the island of Gran Canaria (Spain). J Peripher Nerv Syst 2019;24:131–8. 10.1111/jns.12299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vaeth S, Vaeth M, Andersen H, et al. . Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease in Denmark: a nationwide register-based study of mortality, prevalence and incidence. BMJ Open 2017;7:e018048 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fridman V, Bundy B, Reilly MM, et al. . CMT subtypes and disease burden in patients enrolled in the Inherited Neuropathies Consortium natural history study: a cross-sectional analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015;86:873–8. 10.1136/jnnp-2014-308826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cornett KM, Menezes MP, Bray P, et al. . Phenotypic Variability of Childhood Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. JAMA Neurol 2016;73:645–51. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.0171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Baynam G, Bowman F, Lister K, et al. . Improved diagnosis and care for rare diseases through implementation of precision public health framework. Adv Exp Med Biol 2017;1031:55–94. 10.1007/978-3-319-67144-4_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Park JE, Noh SJ, Oh M, et al. . Frequency of hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies (HNPP) due to 17p11.2 deletion in a Korean newborn population. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2018;13:40 10.1186/s13023-018-0779-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.