Abstract

Aim

The definition of necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) is based on clinical and radiological signs that can be difficult to interpret. The aim of the present study was to validate the incidence of NEC in the Extremely Preterm Infants in Sweden Study (EXPRESS)

Methods

The EXPRESS study consisted of all 707 infants born before 27 + 0 gestational weeks during the years 2004–2007 in Sweden. Of these infants, 38 were recorded as having NEC of Bell stage II or higher. Hospital records were obtained for these infants. Furthermore, to identify missed cases, all infants with a sudden reduction of enteral nutrition, in the EXPRESS study were identified (n = 71). Hospital records for these infants were obtained. Thus, 108 hospital records were obtained and scored independently by two neonatologists for NEC.

Results

Of 38 NEC cases in the EXPRESS study, 26 were classified as NEC after validation. Four cases not recorded in the EXPRESS study were found. The incidence of NEC decreased from 6.3% to 4.3%.

Conclusion

Validation of the incidence of NEC revealed over‐ and underestimation of NEC in the EXPRESS study despite carefully collected data. Similar problems may occur in other national data sets or quality registers.

Keywords: Bells staging, Extremely premature infants, Necrotising enterocolitis, Validation

Abbreviations

- NEC

Necrotising enterocolitis

- NICU

Neonatal intensive care unit

- QI registries

Quality improvement registries

- SIP

Spontaneous intestinal perforation

Key notes.

This study was a systematic validation of necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) in a Swedish cohort of extremely premature infants.

The incidence of NEC after validation was lower than previously reported with a decrease from 6.3% to 4.3%.

The study revealed over‐ and underestimation of the number of NEC cases in extremely preterm infants. Similar problems may occur in other population‐based data sets.

Introduction

Necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) is a devastating disease that still, 100 years after the first case was described in the medical literature, leaves many questions unanswered regarding pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria and the best choice of treatment 1. NEC is difficult to define since it is a diagnosis based on clinical symptoms and signs with variations in the clinical presentation. It is of importance that quality registers and databases of NEC cases are validated and that mimicking diseases are excluded; otherwise, this data cannot be used reliably for research or quality improvement purposes 2. A recent Danish study of 714 premature infants born less than 30 gestational weeks diagnosed with NEC at discharge highlighted the problem with incorrect diagnoses and showed a significantly lower incidence of NEC when each NEC case underwent a rigid validation 3.

National and regional neonatal quality registers are increasingly used on an international level. There are several publications comparing outcomes within, and between quality registers 4. These comparisons have many advantages and may lead to quality improvement; however, there is a risk of differences in classification of the disease that may be important to take into consideration 5.

Bell′s score was presented in 1978 and modified by Kliegman and Walsh nine years later 6, 7. Today, almost 40 years later, the survival rate among infants born before 28 gestational weeks has dramatically improved leading to a different panorama of acquired neonatal intestinal diseases 8. To diagnose NEC in extremely preterm infants is difficult, diseases like spontaneous intestinal perforation (SIP) is often misinterpreted as NEC which can affect the reported incidence of NEC. There is a risk of both over‐ and underestimation of the incidence among extremely preterm infants as they have been described to present with less specific clinical and radiological signs of NEC compared to more mature infants 9.

The Swedish national collaborative project Extremely Preterm Infants in Sweden Study (EXPRESS) is a prospective national study collecting data on preterm infants born before 27 gestational weeks during 2004–2007, including all obstetric and neonatal units in Sweden 10, 11. In the EXPRESS study, NEC was defined according to Bell's Modified staging criteria as Bell stage II or higher 7.

The objective of this study was to identify any possible over‐ or underestimation of the NEC incidence in the Swedish EXPRESS cohort.

Patients and methods

Study population and Setting

The EXPRESS study consisted of 707 live‐born infants of whom 638 were admitted for intensive care 10. Of 707 live‐born infants, 602 survived to 24 hours and 497 to one year of life. The design of the EXPRESS study is described in previous publications 10, 11. A majority of included infants were born and treated at a level three neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). During the three‐year study period, perinatal and neonatal information including NEC was prospectively collected. Missing information was retrieved when possible. Data were also entered in the Swedish Neonatal Quality Registry (SNQ) that includes perinatal background data and extensive health‐related data from the NICU stay 12. A modified version of the data entry form is still used in the SNQ 12 (MedSciNet AB, Stockholm, Sweden) for prospective data collection from all infants admitted to a neonatal ward in Sweden within 28 days of life.

At the time of the EXPRESS study, coordinators at each of the seven health regions established a diagnosis of NEC based on the Bell stage II criteria according to a standard operating procedure. SIP was recognised as a different entity.

The incidence of NEC was reported as 29/497 (5.8%) children surviving one year of age 10. This number is consistent with other Swedish findings 13 but in the lower range comparing to international reports 14. According to the EXPRESS database, among infants who were alive at 24 hours but died within one year of age, 38/602 infants (6.3%) were diagnosed with NEC.

This current study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Helsinki declaration. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at Lund University, Sweden (Dnr 138/2008).

Data collection

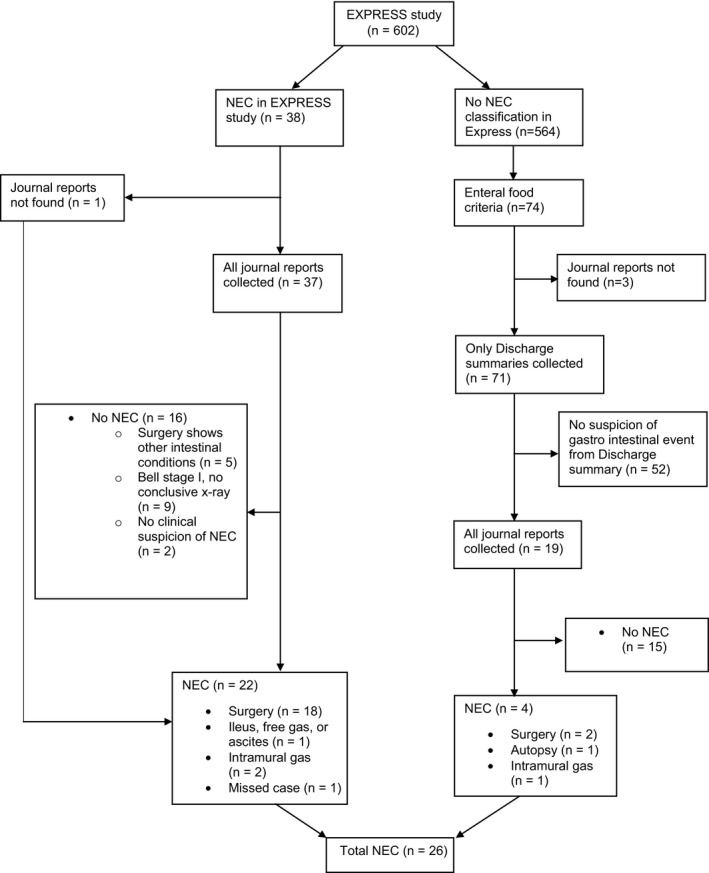

For all infants diagnosed with NEC in the EXPRESS database, hospital charts from the first admission were collected 10, 11. For each infant, the following information was requested: written abdominal X‐ray results, ultrasound results, surgery reports, intestinal biopsy and autopsy protocols (Fig. 1). For four infants, abdominal X‐ray images were collected. For infants who were diagnosed with NEC after transportation to a lower level NICU, hospital records from the second caregiver were also requested.

Figure 1.

Data collection.

To identify missed NEC cases in the EXPRESS study, previously collected data used for a nutritional study were used 15. The nutritional data were obtained from hospital records from birth to 70 days of post‐natal age and covered detailed information on enteral and parenteral intakes. Discharge summaries were collected for all infants who fulfilled one of two criteria: The first criterion was that enteral feeds never exceeded 10% of total fluids within the first 10 days of life. The second criterion was a reduction of enteral feeds to 10% of total fluids or below. For the first 28 days of life, the reduction had to be for two or more days, and enteral feeds prior to the reduction had to be 50% or more of total fluids. After 28 days of life, only one day with a reduction of enteral nutrition was required to fulfil the criterion.

If the discharge summary from the cases with reduced enteral nutrition raised suspicion of any gastrointestinal pathologic event, the same information regarding nutritional intakes was collected as described for infants with a diagnosis of NEC.

All collected data were read and interpreted independently by two neonatologists. Differences in categorisation (n = 4) were settled by consensus. Both the NEC cases in the EXPRESS study and the new cases detected by findings of reduced enteral intake were classified into ten different subgroups according to intervention and Bell's modified staging criteria 7. The subgroups were collapsed into two groups: NEC and No NEC; as shown in Table 1. For four infants, abdominal X‐ray images had to be collected to enable a final classification.

Table 1.

NEC Classification according to validation

| NEC diagnosis in express cohort N (%) | Infants with reduced enteral feedings N (%) | Classified as NEC after validation N | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 38 | 74 | 26 |

| Missing hospital records for validation | 1a | 3 | 1a |

| NEC classification after validation | |||

| No NEC | |||

| No clinical suspicion of NEC | 2 | 54 | 0 |

| Bell stage I, no conclusive X‐ray (no surgery) | 9 | 7 | 0 |

| Surgery showed other intestinal conditions | 5 | 6 | 0 |

| Sum | 16 (42.1) | 70 (94.6) | |

| NEC | |||

| Intramural or portal gas and clinical signs (no surgery) | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Ileus, ascites or free gas on X‐ray and clinical signs (no surgery) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Macroscopic NEC on surgery with confirming biopsy or without biopsy | 18 | 2 | 20 |

| Autopsy with macroscopic and biopsy findings of NEC | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Sum | 22 (57.9) | 4 (5.6) | 26 |

NEC = Necrotising enterocolitis.

Missing case classified as NEC.

Descriptive data were collected from hospital records, SNQ register and the EXPRESS database. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistical software (Version 23.0 for Mac, SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Study population

In the present study, infants from the EXPRESS study who survived 24 hours or more were included (n = 602).

Hospital records for 37 of 38 infants with NEC diagnosis in the original EXPRESS cohort were collected and validated, but the hospital records for one infant were unobtainable. For this infant, the NEC diagnosis was left unchanged. For three infants out of 71 (4%) identified with the criterion for reduced enteral intake, patient records were unobtainable. These three infants were classified as no NEC. Altogether, 56 infants were subjected for a complete review of hospital records. Despite persistent procurement, patient records remained incomplete for 11 of these 56 infants (19%).

Classification of NEC

According to the EXPRESS database, 38/602 infants who survived more than 24 hours were diagnosed with NEC out of which 37 were validated independently by two neonatologists. Nine of these 38 infants died before the age of one year. After validation, 21 of these 38 infants were classified as NEC, one missing case was classified as NEC, and 16 were classified as no NEC.

Among the group of infants with reduced enteral intake (n = 74), four additional cases were classified as NEC (Table 1). Of the 74 infants with reduced enteral feeding, 70 infants including three infants with missing information were classified as no NEC.

Characteristics of the 26 infants with validated NEC are presented in Table 2. No significant differences in background characteristics were observed between patients with and without NEC (Table 2). NEC patients had a significantly higher mortality before discharge (Table 2).

Table 2.

Study Population, children with and without NEC after validation

| Groups | No NECa | NECb | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 576 | 26 | |

| Gestational age (days) | 177 (7.7) | 176 (7.0) | 0.474 |

| Birthweight (gram) | 766 (170) | 748 (170) | 0.596 |

| Birthweight (z‐score) | −0.79 (1.22) | −0.79 (1.31) | 0.985 |

| Male N (%) | 316 (55) | 16 (62) | 0.640 |

| Multiple birth N (%) | 120 (21) | 5 (19) | 1.0 |

| Dead before discharge home N (%) | 96 (17) | 9 (35) | 0.036 |

| NEC diagnosis in hospital records N (%) | n/a | 19 (73)c |

NEC = Necrotising enterocolitis.

Values are mean (SD).

Statistics used: chi‐square, yates correction for continuity and t‐test.

No NEC = EXPRESS infants alive at 24 hours and no NEC diagnosis after validation.

NEC = EXPRESS infants alive at 24 hours with NEC diagnosis after validation.

One child missing.

Characteristics of misclassified cases

Sixteen of total 38 NEC cases in the EXPRESS study, were classified as no NEC cases (Table 1). Five infants with NEC diagnosis in the EXPRESS study who underwent surgery were classified as no NEC by the validation. Of those, three were recognised as SIP, one as volvulus and one as a meconium ileus (Table 3). Two of the NEC cases in the EXPRESS study were classified as no clinical suspicion of NEC and nine cases as Bell stage I. Three of these nine infants showed clinical symptoms of Bell stage II and six clinical symptoms of Bell stage I. None of them had unambiguous radiological findings of ileus, pneumatosis intestinalis, portal venous gas, ascites or pneumoperitoneum and were therefore classified as Bell stage I.

Table 3.

Excluded and added NEC cases by validation

| Infants validated as no NEC in the EXPRESS study. N = 16 | |

|---|---|

| Number of infants | Reason to reclassify |

| 1 | Surgery showed volvulus |

| 1 | Surgery showed meconium ileus |

| 3 | Surgery showed spontaneous intestinal perforation |

| 2 | No clinical suspicion of NEC |

| 9 | Clinical Signs Bell Stage ≤II and no conclusive X‐ray (no surgery) |

| Added NEC cases found by reduced enteral nutrition. N = 4 | |

|---|---|

| Number of infants | Description |

| 1 | Sepsis and NEC according to autopsy |

| 1 | Surgery showed macroscopic NEC, biopsy missing |

| 1 | Underwent surgery and died one month later. Autopsy showed NEC. NEC diagnosis in hospital records |

| 1 | Secondary interpretation of X‐rays showed intramural gas. NEC diagnosis in hospital records |

NEC = Necrotising enterocolitis.

In the group of infants detected by reduced enteral feeding (N = 74), four infants were classified as NEC after validation. Two of the NEC cases showed macroscopic findings of NEC during surgery, one showed macroscopic findings of NEC on autopsy and one had explicit radiological findings. Seven infants were classified as Bell stage I of them, three had clinical symptoms of Bell stage II but none had radiological findings of Bell stage II (Table 3). These seven infants were classified as no NEC.

Impact on incidence and mortality

The incidence of NEC before validation was 38/602 children (6.3%), and after validation, the incidence was 26/602 children (4.3%). Mortality before discharge among NEC cases in the original EXPRESS study database was 9/38 children (23.7%) and after validation 9/26 children (34.6%).

Discussion

The present study showed a lower incidence of NEC after validation of the NEC cases in the EXPRESS study, a population‐based prospective observational study of extremely preterm infants. This lower NEC incidence is interesting since the NEC incidence in the EXPRESS study was already low, suggesting a very low NEC incidence in Sweden, possibly due to the widespread use of breast milk and the availability of donor human milk banks 16.

Importantly, the study also shows a risk of overestimating as well as underestimating the number of NEC cases in extremely preterm infants. This risk underlines the need for validation of the NEC diagnosis in clinical research as well as in neonatal quality improvement (QI) registries. QI registries are essential tools for clinical evaluation, benchmarking and research. To be able to compare national and international data there is a need for robust diagnostic criteria.

Eleven of the 38 NEC diagnosed infants in the EXPRESS study did not undergo surgery and had no signs of NEC on ultrasound or X‐ray (Table 1). In the EXPRESS study, NEC was defined as Bell stage II or above, which requires radiological findings with ileus, pneumatosis intestinalis or portal venous gas 6, 7. In preterm infants, it is difficult to differentiate between NEC and other diagnoses such as SIP and even harder to validate the diagnosis retrospectively. A septic episode may result in intestinal paralysis and dilatation that may clinically mimic NEC without having a true intestinal inflammation or necrosis. In several of the infants originally defined as NEC, the diagnosis could not be confirmed in this validation. This validation pinpoints that early stages of NEC are challenging to diagnose in extremely preterm infants. This challenge is further complicated by the fact that the modified Bell's criteria are not validated for this group of patients. It has been suggested by Gordon et al. 17 that the criteria should be replaced in favour of a more clinical approach focused on the pathophysiological genesis. This strategy suggests a classification of NEC into five different subgroups based on risk factors and triggers: Term‐Ischaemic, red blood cell transfusions, cow milk intolerance, contagion and extreme prematurity 18. However, there are currently no validated criteria for this type of subclassification of NEC.

Recently, Battersby et al. 19 suggested a new definition of NEC based on weighted scores depending on clinical and radiological findings and a cut‐off depending on gestational age. By using gestational age‐specific definitions in four categories, they showed a sensitivity of 76.5% and a specificity of 74.4% for predicting infants who underwent laparotomy. This definition deals with the fact that NEC has a different clinical panorama depending on gestational age but does not prevent the erroneous inclusion of other diseases. As a recent Danish validation of NEC diagnoses at discharge showed, there is a high risk to misdiagnose SIP as NEC when the Bell's criteria are used 3. The strict definition with mandatory surgical and autopsy findings of a necrotic intestine, as proposed in the studies referred to, may result in a loss of sensitivity.

In recent years, abdominal ultrasound has been shown to be a useful tool in the diagnosis of NEC in extremely preterm infants 20, but ultrasound criteria are not included in the Bell classification.

Among the cases that underwent surgery, five cases did not have NEC at validation; three were categorised as SIP, which mimics NEC in many ways but has different pathogenesis and a more favourable outcome 21. If surgical reports had been taken into account in the EXPRESS study, these cases could have been separated as well as the other two cases: one volvulus and one meconium ileus.

It has been shown that just by removing SIP cases from cases diagnosed as NEC, the time distribution of the remaining NEC cases complies with Sartwell's model of incubation time 22, 23. This finding shows that a definition of NEC by removing SIP cases could be useful for better understanding the triggers of NEC.

Our results show that using Bell's criteria, at least four infants with a diagnosis of NEC were not identified in the EXPRESS study (Table 1). Two of these cases underwent surgery with clear NEC findings; one had pneumatosis intestinalis and one had explicit findings of NEC on autopsy.

The data in the EXPRESS study became part of the SNQ register that collects peri‐ and neonatal data on all infants in Sweden admitted for neonatal care. This register is only one of 96 quality registers within the Swedish healthcare sector in 2017 24. It is resource efficient to use data from quality registries for research purposes, but it must not be forgotten that national data collected by a large number of people may contain errors that may abate their usefulness. Although EXPRESS data were collected within the framework of a prospective study by dedicated researchers the present study detected under classification and overclassification of infants with NEC.

The first strength of this study was the extent and quality of the EXPRESS study, in which rigorously prospective data were collected of every child born in Sweden surviving 24 hours under gestation week 27 during three years. The second strength was that the study showed that nutritional data could be used to find missed NEC cases. A third strength was that each case was independently interpreted by two neonatologists.

Weaknesses were the difficulty of a retrospective diagnosis. In few cases, it was challenging to retrospectively make a classification and reconstruction of a pathological intestinal event from journal reports with redundant clinical information. This challenge in addition to a risk of subjectivity in the interpretation, especially for the suspicious NEC cases with diffuse radiological findings is a weakness of this study. Moreover, there were difficulties to obtain complete hospital records as a consequence of a broad geographical spread (12 NICUs), undigitalised records and many different records for each infant. This was not considered to affect interpretation.

Conclusion

The NEC incidence in the EXPRESS study was lower after validation of the reported NEC cases. When excluding the suspected cases, the NEC incidence was 4.3% among infants born before gestational week 27 + 0 completed weeks. A correct diagnosis of NEC Bell stage II in extremely preterm infants is difficult leading to a risk of both over‐ and underestimation of the incidence. Improved classification of NEC is of great importance for quality improvement in the future.

Funding

This study was financed by grants from the ALF agreement between the Swedish government and county councils to Sahlgrenska University Hospital and Umeå University Hospital and by grants from the Swedish Research Council (2016‐02095).

Conflict of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

We thank Denise Jansson, Ann‐Cathrine Berg for data collection and Cornelia Späth for analysing nutritional data.

The copyright line for this article was changed on 6 February 2019 after original online publication.

References

- 1. Sharma R, Hudak ML. A clinical perspective of necrotizing enterocolitis: past, present, and future. Clin Perinatol 2013; 40: 27–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gordon PV, Swanson JR, Attridge JT, Clark R. Emerging trends in acquired neonatal intestinal disease: is it time to abandon Bell's criteria? J Perinatol 2007; 27: 661–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Juhl SM, Hansen ML, Fonnest G, Gormsen M, Lambaek ID, Greisen G. Poor validity of the routine diagnosis of necrotising enterocolitis in preterm infants at discharge. Acta Paediatr 2017; 106: 394–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shah PS, Lui K, Sjors G, Mirea L, Reichman B, Adams M, et al. Neonatal outcomes of very low birth weight and very preterm neonates: an international comparison. J Pediatr 2016; 177: e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gliklich RE, Dreyer NA, Leavy NA, editors. Registries for evaluating patient outcomes: a user's guide. 3 ed Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bell MJ, Ternberg JL, Feigin RD, Keating JP, Marshall R, Barton L, et al. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging. Ann Surg 1978; 187: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Walsh MC, Kliegman RM. Necrotizing enterocolitis: treatment based on staging criteria. Pediatr Clin North Am 1986; 33: 179–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Luig M, Lui K, NSW & ACT NICUS Group . Epidemiology of necrotizing enterocolitis–Part II: risks and susceptibility of premature infants during the surfactant era: a regional study. J Paediatr Child Health 2005; 41: 174–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Palleri E, Aghamn I, Bexelius TS, Bartocci M, Wester T. The effect of gestational age on clinical and radiological presentation of necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr Surg 2018; 53: 1660–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. EXPRESS Group , Fellman V, Hellstrom‐Westas L, Norman M, Westgren M, Kallen K, et al. One‐year survival of extremely preterm infants after active perinatal care in Sweden. JAMA 2009; 301: 2225–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. EXPRESS Group . Incidence of and risk factors for neonatal morbidity after active perinatal care: extremely preterm infants study in Sweden (EXPRESS). Acta Paediatr 2010; 99: 978–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Register SNQ . Om SNQ 2018 [Internet]. Swedish Neonatal Quality Register, 2018. Available at: http://www.medscinet.com/pnq/about.aspx?lang=3 (accessed on August 1, 2018).

- 13. Ahle M, Drott P, Andersson RE. Epidemiology and trends of necrotizing enterocolitis in Sweden: 1987‐2009. Pediatrics 2013; 132: e443–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Neu J, Walker WA. Necrotizing enterocolitis. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 255–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stoltz Sjostrom E, Ohlund I, Ahlsson F, Engstrom E, Fellman V, Hellstrom A, et al. Nutrient intakes independently affect growth in extremely preterm infants: results from a population‐based study. Acta Paediatr 2013; 102: 1067–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stoltz Sjostrom E, Ohlund I, Tornevi A, Domellof M. Intake and macronutrient content of human milk given to extremely preterm infants. J Hum Lact 2014; 30: 442–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gordon PV, Swanson JR, MacQueen BC, Christensen RD. A critical question for NEC researchers: can we create a consensus definition of NEC that facilitates research progress? Semin Perinatol 2017; 41: 7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gordon P, Christensen R, Weitkamp JH, Maheshwari A. Mapping the New World of Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC): review and Opinion. EJ Neonatol Res 2012; 2: 145–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Battersby C, Longford N, Costeloe K, Modi N, Group UKNCNES . Development of a gestational age‐specific case definition for neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. JAMA Pediatr 2017; 171: 256–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Palleri E, Kaiser S, Wester T, Arnell H, Bartocci M. Complex fluid collection on abdominal ultrasound indicates need for surgery in neonates with necrotizing enterocolitis. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2017; 27: 161–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gordon PV, Attridge JT. Understanding clinical literature relevant to spontaneous intestinal perforations. Am J Perinatol 2009; 26: 309–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gonzalez‐Rivera R, Culverhouse RC, Hamvas A, Tarr PI, Warner BB. The age of necrotizing enterocolitis onset: an application of Sartwell's incubation period model. J Perinatol 2011; 31: 519–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sartwell PE. The distribution of incubation periods of infectious disease. Am J Epidemiol 1995; 141: 386–94. discussion 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Landsting SKo. Om nationella kvalitetsregister 2017 [Internet]. Stockholm: Sveriges Kommuner och Landsting, 2018. Available at: http://kvalitetsregister.se/tjanster/omnationellakvalitetsregister.1990.html (accessed on August 1, 2018). [Google Scholar]