Abstract

Background

Africa has the highest rates of child mortality. Little is known about outcomes after hospitalization for children with very severe anemia.

Objective

To determine one year mortality and predictors of mortality in Tanzanian children hospitalized with very severe anemia.

Methods

We conducted a prospective cohort study enrolling children 2–12 years hospitalized from August 2014 to November 2014 at two public hospitals in northwestern Tanzania. Children were screened for anemia and followed until 12 months after discharge. The primary outcome measured was mortality. Predictors of mortality were determined using Cox regression analysis.

Results

Of the 505 children, 90 (17.8%) had very severe anemia and 415 (82.1%) did not. Mortality was higher for children with very severe anemia compared to children without over a one year period from admission, 27/90 (30.0%) vs. 59/415 (14.2%) respectively (Hazard Ratio (HR) 2.42, 95% Cl 1.53–3.83). In-hospital mortality was 11/90 (12.2%) and post-hospital mortality was 16/79 (20.2%) for children with very severe anemia. The strongest predictors of mortality were age (HR 1.01, 95% Cl 1.00–1.03) and decreased urine output (HR 4.30, 95% Cl 1.04–17.7).

Conclusions

Children up to 12 years of age with very severe anemia have nearly a 30% chance of mortality following admission over a one year period, with over 50% of mortality occurring after discharge. Post-hospital interventions are urgently needed to reduce mortality in children with very severe anemia, and should include older children.

Introduction

Very severe anemia (hemoglobin concentration less than 5.0 g/dL) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality among children in Africa. Of hospitalized children, 12 to 29% have very severe anemia, and the in-hospital mortality of these children range between 4 to 17% [1–9]. Little is known about the long-term outcomes for children with very severe anemia after hospitalization [10]. The few data that have been published have been limited to children under five years of age [9]. Studies are lacking regarding long-term outcomes after hospitalization that include older children with very severe anemia.

Therefore, we conducted a prospective cohort study of Tanzanian children up to 12 years of age hospitalized with very severe anemia and followed until one-year after hospital discharge. Our study objectives were: 1) to determine the prevalence of very severe anemia for hospitalized children, 2) to compare all-cause mortality in children with very severe anemia to children without very severe anemia up to one year post-hospitalization, and 3) to identify predictors of mortality for children with very severe anemia.

Methods

Study site

This study is a secondary analysis of a prospective cohort study where we consecutively screened and enrolled children hospitalized on the pediatric wards of two public hospitals in northwestern Tanzania and followed for one-year post hospitalization [11]. The original cohort study used convenience sampling for a sample size of 500 participants to enroll from the two hospitals. Bugando Medical Center (BMC) and Sekou-Toure Regional Referral Hospital (STH) are in the city of Mwanza, the second largest city in Tanzania and the capital of the Mwanza region. BMC is a public tertiary hospital that serves as the zonal referral hospital for northwestern Tanzania with a catchment area of approximately 16 million people. BMC has 1,000 inpatient beds and approximately 3,500 pediatric hospitalizations per year. STH is a public regional hospital for Mwanza region with a population of approximately 3 million people. STH has 320 inpatient beds and approximately 2,000 pediatric hospitalizations per year.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Children 2–12 years of age hospitalized in the medical ward of BMC or STH were eligible for enrollment in the original cohort study. The original cohort study did not include children under 2 years of age, since mortality in this age group was known to be high and largely due to infectious diseases [11]. Children above 12 years were excluded since they are admitted to the adult wards at BMC and STH. The parent or guardian of a potential participant was provided with information regarding the study within 12 hours of admission. Children were enrolled only after obtaining informed consent from a parent or guardian by a study member. Study participants with multiple hospitalizations to BMC or STH during the study period were only enrolled during their first hospitalization. Children who were referral cases from another hospital, like a district hospital or another in-patient health facility, were excluded from the study.

Study procedures

On the day of enrollment, a modified version of the World Health Organization (WHO) STEPS questionnaire was administered in Swahili by a Tanzanian study investigator to the parent or guardian [12]. The WHO STEPS questionnaire includes questions regarding socioeconomic status, medical history, prior testing, diagnosis and treatment for diseases as well as standard protocols for physical examination. After completing the questionnaire, the study investigator conducted a standardized physical examination including the measurement of vital signs, weight and height. An axillary temperature was taken. Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a digital scale (DETECTO, USA), which was adjusted to zero before each measurement. If the child was unable to stand, her weight was taken on a hanging scale. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a stadiometer. If the child was unable to stand, her height was measured while lying down.

All children underwent measurements of hemoglobin, glucose, creatinine, and urine dipstick testing as standard procedures of hospitalization at BMC and STH. Hemoglobin levels were measured by Hemo Control Hemoglobin Analyzer (EKF Diagnostics, Germany). Glucose levels were measured by Ascensia Glucometer (Bayer Healthcare, Germany). Serum creatinine levels were measured using Cobas Integra 400 Plus Analyzer (Roche Diagnostic Limited, Switzerland). An estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the bedside Schwartz equation as recommended by international guidelines [13]. A urine dipstick was used to test for proteinuria and hematuria (Multistix 10SG, Siemens, USA). At the time of hospitalization, by national policy, all children were offered HIV testing. Permission was obtained for testing of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) according to the Tanzania national guidelines [14].

Study definitions

Severity of anemia was defined according to WHO reference standard for anemia [15]. Study participants with a hemoglobin concentration less than 5.0 g/dL were classified as very severe anemia.

Clinical procedures and diagnoses

Disease management was conducted by the hospital clinicians in accordance with hospital and Tanzanian management protocols. Per standard hospital policy, children with very severe anemia received an urgent blood transfusion (whole blood 20 milliliters per kilogram body weight). BMC and STH have used a standard list of recommended pediatric diagnoses adapted from the WHO’s International Classification of Disease version 10 (ICD-10) [16]. Each study participant had a diagnosis recorded for this study that was based on the assessment by the clinicians caring for the child. For a child with multiple diagnoses (e.g., severe malnutrition and diarrheal disease), a single diagnosis was recorded for this study that was based on the primary diagnosis recorded by the clinicians caring for the child. Caretakers were given standard discharge instructions and told to follow-up in clinic within 2 weeks of discharge or sooner if necessary.

Follow-up of study participants

A total of three mobile phone numbers were obtained from all participants’ caretakers at the time of discharge. This included one number for the study participant’s parent or guardian, and two additional numbers for relatives or close friends. Follow-up phone calls were made at 3, 6 and 12 months post-discharge by a Tanzanian study investigator. A child was considered lost to follow-up if the study investigator could not reach a participants’ parent or relative/close friends via the three mobile phone numbers obtained at time of discharge. If a study participant could not be reached at 3 months, attempts were also made at 6 and 12 months. If the child had died, the date of death was also determined.

Study outcome

The primary study outcome was all-cause mortality. Mortality was classified as in-hospital if it occurred during the index hospitalization and post-hospital if it occurred in the year that followed the index hospitalization.

Data analysis

Data were entered into Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, USA) and analyzed using Stata version 14 (College Station, Texas, USA). Categorical variables were described as proportions (percentages), and continuous variables were described as means (standard deviations). For all cross-sectional analyses, a chi-squared test was used for comparing categorical variables and a Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for continuous variables. Cox regression models were used for all survival analyses to compare outcomes between study groups and to determine predictors of mortality. All variables with p < 0.05 in the univariable model along with age and sex were entered into the multivariable model. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to display incident mortality. A log-rank test was used to determine if mortality incidence differed by severity of anemia. Study participants lost to follow-up were censored at the last contact date. All available data were included in all calculations. No variable was missing for more than 14 participants. A two-sided p-value of < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant in all analyses.

Ethical consideration

The study was approved by Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences/Bugando Medical Center (BREC/001/2008), Weill Cornell Medical College (1504016104) and the National Institute for Medical Research in Tanzania (NIMR/HQ/R.8c/Vol.II/317). Participants were enrolled only after obtaining informed consent from one of their parents or guardian. Assent was obtained for children 7 years and above. Parents also consented to receive phone calls at either their own mobile phone number or the mobile phone numbers they provided for relatives or friends. They agreed that if they were not available to receive the phone call, relatives or friends could provide information about the vital status of the child. All study procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Results

Study enrollment

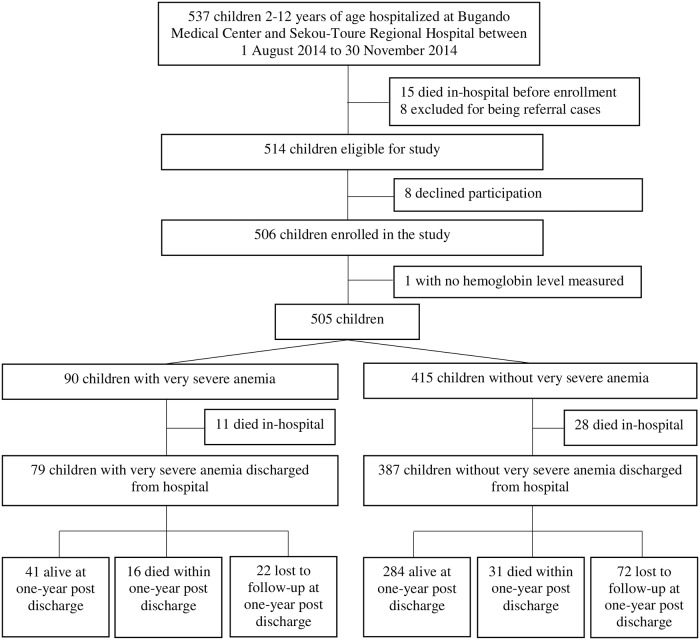

From 1st August 2014 to 30th November 2014, five hundred and thirty seven children were hospitalized in the pediatric wards of BMC and STH (Fig 1). Of the 537 children hospitalized, 15 died before enrollment occurred, 8 were excluded for being referral cases from another hospital, and 8 declined participation. The remaining 506 children (94.2%) were enrolled, with 461/506 (91.1%) at BMC and 45/506 (8.9%) at STH. One participant of the 506 children did not have a hemoglobin level measured at BMC.

Fig 1. Flow diagram of study participants from hospitalization to one-year post discharge outcome.

Of the 505 children, 90 (17.8%) had very severe anemia and 415 (82.1%) did not. The in-hospital mortality rates were 11/90 (12.2%) for children with very severe anemia and 28/415 (6.7%) for children without very severe anemia. Of the 466 children who were discharged from the hospital, mobile phone contact was made with 458/466 (98.3%) children’s parents (or designated proxies) at 3 months, 409/466 (87.8%) at 6 months, and 372/466 (79.8%) at 12 months. Twenty-two of 79 (27.8%) children with very severe anemia and 72/387 (18.6%) children without very severe anemia were lost to follow-up at 12 months.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the two study groups are described in Table 1. Children with very severe anemia were found to be older (59.1 vs 53.6 months, p = 0.027). Other notable differences were significantly less reports of fever, more reports of taking herbal medication, lower diastolic blood pressure, lower Glasgow coma scores, more children with pallor, higher eGFR, more children with hematuria, more children with sickle cell disease, and fewer children with diarrheal, respiratory, urinary tract infection or neurologic diseases. The mean hemoglobin level for children with very severe anemia was 3.6 g/dL compared to 8.8 g/dL for children without very severe anemia.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of children with very severe anemia and without very severe anemia.

| Variables | Children with very severe anemia (n = 90) |

Children without very severe anemia (n = 415) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | |||

| Female | 34 (37.7%) | 179 (43.1%) | 0.351 |

| Age (months) | 59.1 (31) | 53.6 (32) | 0.027 |

| Under 5 years | 53 (58.9%) | 276 (66.5%) | |

| 5–12 years | 37 (41.1%) | 139 (33.5%) | |

| Lake/pond as water source | 40 (44.4%) | 152 (36.6%) | 0.166 |

| Pit latrine at home | 58 (64.4%) | 245 (59.0%) | 0.342 |

| Reported on Hospitalization | |||

| Fever | 14 (15.5%) | 122 (29.3%) | 0.007 |

| Vomiting | 71 (78.8%) | 297 (71.5%) | 0.157 |

| Diarrhea | 71 (78.8%) | 292 (70.3%) | 0.103 |

| Decreased urine output | 6 (6.6%) | 24 (5.7%) | 0.748 |

| Taking herbal medication | 35 (38.8%) | 112 (26.9%) | 0.024 |

| Signs on Physical Examination | |||

| Temperature (Celsius) | 37.3 (1) | 37.3 (1) | 0.614 |

| Heart rate (beats per minute) | 118 (21) | 114 (22) | 0.084 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 91 (13) | 94 (14) | 0.217 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 60 (9) | 62 (10) | 0.043 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths per minute) | 34 (13) | 32 (12) | 0.140 |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | 95.4 (4) | 95.7 (5) | 0.100 |

| Nutritional status | |||

| Severe malnutritiona | 16 (17.7%) | 54 (13.0%) | 0.119 |

| Moderate malnutritionb | 15 (16.6%) | 61 (14.6%) | |

| Mild malnutritionc | 22 (24.4%) | 73 (17.5%) | |

| Normal | 37 (41.1%) | 227 (54.6%) | |

| Glasgow coma score | |||

| < 13 | 2 (2.2%) | 14 (3.3%) | 0.005 |

| 13–14 | 6 (6.6%) | 5 (1.2%) | |

| 15 | 82 (91.1%) | 396 (95.4%) | |

| Pallor | 64 (71.1%) | 114 (27.4%) | <0.001 |

| Edema | 17 (18.8%) | 49 (11.8%) | 0.071 |

| Laboratory Investigation | |||

| Random blood glucose (g/dL) | 5.7 (1.8) | 6.0 (5.3) | 0.701 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (mL/min/1.73m2) | 143.0 (68) | 107.0 (56) | <0.001 |

| Proteinuria by urinalysis | 20 (22.2%) | 77 (18.5%) | 0.423 |

| Hematuria by urinalysis | 7 (7.7%) | 13 (3.1%) | 0.041 |

| HIV positive | 5 (5.5%) | 25 (6.0%) | 0.865 |

| Hemoglobin level (g/dL) | 3.6 (0.8) | 8.8 (2) | <0.001 |

| Primary Diagnostic Category | |||

| Malaria | 14 (16.6%) | 50 (12.0%) | 0.365 |

| Sickle cell disease | 25 (27.7%) | 36 (8.6%) | <0.001 |

| Severe malnutrition | 5 (5.5%) | 28 (6.9%) | 0.623 |

| Diarrheal diseases | 2 (2.2%) | 58 (13.9%) | 0.002 |

| Respiratory infections | 3 (3.3%) | 57 (13.7%) | 0.006 |

| Heart disease | 2 (2.2%) | 21 (5.0%) | 0.242 |

| Cancer | 4 (4.4%) | 16 (3.8%) | 0.795 |

| Septic shock | 2 (2.2%) | 12 (2.8%) | 0.673 |

| Urinary tract infection | 1 (1.1%) | 35 (8.4%) | 0.014 |

| Neurologic diseases | 1 (1.1%) | 32 (7.7%) | 0.017 |

Data are number of participants (%) or mean (SD), unless otherwise specified.

a Weight-for-Height Z score < -3 SD

b Weight-for-Height Z score < -2 and ≥ -3 SD

c Weight-for-Height Z score < -1 and ≥ -2 SD

Prevalence of very severe anemia

Among all participants, 90/505 (17.8%) were found to have a hemoglobin level of less than 5.0 g/dL upon admission (Table 2). A total of 203/505 (40.2%) children had either severe or very severe anemia. The total number of children that had any level of anemia was 442/505 (87.5%).

Table 2. Severity of anemia and overall mortality at 12 months for all study participants.

| Total (N = 505) |

Dead (N = 86) |

Alive (N = 419) |

HR [95% CI] |

p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin level (g/dL) | 7.9 (2.7) |

6.5 (2.6) |

8.1 (2.6) |

0.82 [0.75–0.88] |

<0.001 | |

| Anemia severitya | ||||||

| Very severe anemia | 90 (17.8%) |

27 (30.0%) |

63 (70.0%) |

4.33 [1.66–11.26] |

0.003 | <0.001b |

| Severe anemia | 113 (22.4%) |

24 (21.2%) |

89 (78.8%) |

2.77 [1.06–7.28] |

0.038 | |

| Moderate anemia | 187 (37.0%) |

24 (12.8%) |

163 (87.2%) |

1.55 [0.59–4.07] |

0.370 | |

| Mild anemia | 52 (10.3%) |

6 (11.5%) |

46 (88.5%) |

1.50 [0.45–4.92] |

0.502 | |

| No anemia | 63 (12.5%) |

5 (7.9%) |

58 (92.1%) |

Reference | ||

Data are number of participants (%) or mean (SD)

a Defined according to WHO reference standard for anemia

b p trend

Mortality

Overall one-year mortality was significantly higher for children with very severe anemia compared to children without very severe anemia, 27/90 (30.0%) vs. 59/415 (14.2%) respectively (Hazard Ratio [HR] 2.42, 95% Cl 1.53–3.83, p < 0.001). In-hospital mortality was higher for children with very severe anemia compared to those without very severe anemia, 11/90 (12.2%) vs. 28/415 (6.7%) respectively (HR 1.89, 95% Cl 0.94–3.79, p = 0.073). Post-hospital mortality was significantly higher for children with very severe anemia compared to those without very severe anemia, 16/79 (20.2%) vs. 31/387 (8.0%) respectively (HR 2.98, 95% Cl 1.62–5.45, p < 0.001). For post-hospital mortality, the median time-point for death among children with very severe anemia was 57 days after discharge, compared to 190 days after discharge for those without very severe anemia.

Based on hospital sites, the overall one-year mortality rate for children admitted to BMC with very severe anemia was 26/79 (32.9%), compared to children without very severe anemia 57/381 (15.0%). The overall one-year mortality rate for children admitted to STH with very severe anemia was 1/11 (9.1%), compared to children without very severe anemia 2/34 (5.9%).

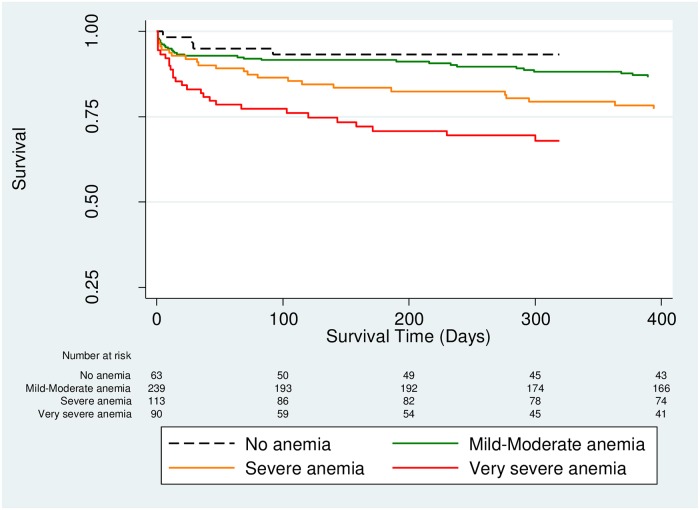

Children with very severe anemia had a 4.3-fold increase risk of mortality compared to children without any anemia (HR 4.33, 95% Cl 1.66–11.26, p = 0.003) (Table 2). As the severity of anemia increased, the hazards of mortality increased (Fig 2). For every 1 g/dL decrease in hemoglobin level, the risk of death increased by 18% for all study participants (HR 0.82, 95% Cl 0.75–0.88, p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Fig 2. Kaplan Meier survival curves comparing severity of anemia (p < 0.001 by log-rank test).

Factors associated with mortality

All variables listed in Table 1 were analyzed as possible predictors of mortality for children with very severe anemia (Tables 3 and 4). The significant independent predictors of mortality by multivariate Cox regression analysis were older age (HR 1.01, 95% Cl 1.00–1.03, p = 0.006), and reports of decreased urine output (HR 4.30, 95% Cl 1.04–17.7, p = 0.044). In regard to older age, overall mortality was significantly higher for children 5 years and older with very severe anemia compared to children under 5 years of age with very severe anemia, 17/37 (45.9%) vs. 10/53 (18.9%) respectively (HR 2.79, 95% Cl 1.27–6.10, p < 0.010).

Table 3. Predictors of mortality for children with very severe anemia by univariate analysis.

| Variables | Hazard Ratio [95% CI] | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | ||

| Female | 1.01 [0.46–2.21] | 0.937 |

| Age (months) | 1.01 [1.00–1.02] | 0.036 |

| Categorical Age | ||

| Under 5 years | Reference | |

| 5–12 years | 2.79 [1.27–6.10] | 0.010 |

| Lake/pond as water source | 0.60 [0.27–1.34] | 0.214 |

| Pit latrine at home | 0.97 [0.44–2.14] | 0.960 |

| Reported on Hospitalization | ||

| Fever | 0.76 [0.28–2.00] | 0.580 |

| Vomiting | 1.27 [0.53–3.00] | 0.586 |

| Diarrhea | 0.38 [0.11–1.29] | 0.124 |

| Decreased urine output | 11.4 [4.2–31.20] | <0.001 |

| Taking herbal medication | 1.23 [0.57–2.67] | 0.583 |

| Signs on Physical Examination | ||

| Temperature (Celsius) | 0.76 [0.51–1.13] | 0.183 |

| Heart rate (beats per minute) | 0.99 [0.97–1.01] | 0.597 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 0.98 [0.95–1.01] | 0.267 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 0.93 [0.89–0.97] | 0.001 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths per minute) | 1.02 [1.00–1.05] | 0.024 |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | 0.92 [0.87–0.97] | 0.003 |

| Nutritional status | ||

| Severe malnutritiona | 1.47 [0.54–3.99] | 0.444 |

| Moderate malnutritionb | 0.84 [0.26–2.63] | 0.766 |

| Mild malnutritionc | 0.95 [0.35–2.57] | 0.923 |

| Glasgow coma score | 0.58 [0.35–0.96] | 0.036 |

| Pallor | 1.66 [0.67–4.12] | 0.272 |

| Edema | 3.80 [1.72–8.35] | 0.001 |

| Laboratory Investigation | ||

| Random blood glucose (g/dL) | 1.00 [0.82–1.22] | 0.956 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (mL/min/1.73m2) | 0.99 [0.99–1.00] | 0.755 |

| Proteinuria by urinalysis | 2.16 [0.97–4.82] | 0.059 |

| Hematuria by urinalysis | 2.16 [0.74–6.27] | 0.153 |

| HIV positive | 3.23 [0.97–10.8] | 0.056 |

| Hemoglobin level (g/dL) | 0.66 [0.43–1.01] | 0.058 |

| Diagnostic Category | ||

| Malaria | 0.38 [0.09–1.64] | 0.199 |

| Sickle cell disease | 1.04 [0.45–2.39] | 0.915 |

| Severe malnutrition | 0.63 [0.08–4.69] | 0.658 |

| Diarrheal diseases | 1.89 [0.25–13.98] | 0.531 |

| Respiratory infections | 2.07 [0.27–15.39] | 0.475 |

| Heart disease | 1.94 [0.26–14.34] | 0.515 |

| Cancer | 3.23 [0.97–10.77] | 0.056 |

| Septic shock | 29.33 [4.90–175.52] | <0.001 |

| Urinary tract infection | NA | NA |

| Neurologic diseases | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable

a Weight-for-Height Z score < -3 SD

b Weight-for-Height Z score < -2 and ≥ -3 SD

c Weight-for-Height Z score < -1 and ≥ -2 SD

Table 4. Predictors of mortality for children with very severe anemia by multivariate analysisa.

| Variable | Hazard Ratio [95% CI] | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | 1.01 [1.00–1.03] | 0.006 |

| Decreased urine output | 4.30 [1.04–17.7] | 0.044 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 0.94 [0.88–1.00] | 0.062 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths per minute) | 1.03 [0.99–1.06] | 0.066 |

| Edema | 2.21 [0.82–5.94] | 0.114 |

| Glasgow coma score | 1.69 [0.63–4.51] | 0.287 |

| Septic shock | 5.32 [0.18–156.88] | 0.333 |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | 0.98 [0.91–1.05] | 0.673 |

| Female | 0.95 [0.38–2.36] | 0.916 |

a Adjusted for age and sex

Comparison of predictors for in-hospital and post-hospital mortality for children with very severe anemia are in S1 Table.

Discussion

Children admitted to hospitals in Tanzania with very severe anemia suffer from strikingly high rates of mortality in the year after an index hospitalization. In our study, 30% of children with very severe anemia died within one year of hospitalization. Fifty-nine percent of those deaths occurred during the post-hospital period. This confirms and extends findings from a prior study of hospitalized Malawian children under the age of 5 years with hemoglobin less than 5.0 g/dL [9]. In this study, 17% of these children with hemoglobin less than 5.0 g/dL died in the 18 months after hospital admission. The majority these deaths (63%) occurred after hospital discharge. We demonstrate that even older children with very severe anemia suffer from alarmingly high rates of mortality in the post-hospital period. In fact, children 5 years of age and older with very severe anemia had even higher mortality than children under 5 years of age with very severe anemia. In regards to reducing child mortality, children under the age of 5 have received the vast majority of the attention. Efforts should be made to ensure older children also benefit from health policies and interventions [17–18].

For the deaths that occurred post-hospital for children with very severe anemia, more than half the deaths occurred within 2 months of discharge. This finding supports the idea of a period of vulnerability following discharge. A high post-hospital mortality rate in the early discharge period has also been shown for children with malaria, diarrhea and for general admissions [19–22]. This may be partly explained by the “post-hospital syndrome”, which has been described as an acquired transient period of vulnerability following discharge [23]. However, post-hospital mortality is not merely an issue of disease pathology, but also has a complex socioeconomic overlay in our setting. For example, problems related to poverty where finding funds for transportation to health facilities or paying for medical care is challenging, low parental education, gender inequities like husbands making decisions while mothers having better understanding of the needs of their children, parental employment where work affects the ability of parents to seek medical attention for their children, and seeking traditional medicine healers can all reduce adherence to medications and clinic follow-up, and thereby lead to higher mortality [24–26].

Low hemoglobin level is a strong predictor of mortality. In our study, children with very severe anemia were 4.3 times more likely to die, compared to children without any anemia. Our study also found for each 1 g/dL decrease in hemoglobin, the risk of death increased by 18%. This appears to be consistent with other published data. A meta-analysis of nearly 12,000 children from six African countries looking at the association between anemia and mortality reported an odds ratio of 0.76 (95% Cl 0.62–0.93), indicating that for each 1 g/dL decrease in hemoglobin, the risk of death increased by 24% [27]. For children with very severe anemia, attention to older aged children is critical, as increasing age appears to be a predictor of mortality. One speculation is older children are more likely to have chronic diseases associated with anemia, like sickle cell disease or cancer, compared to younger children who have not acquired chronic diseases yet. The ability for health facilities in low resource settings to diagnose children of all ages with anemia and treat with adequate blood supply if needed will be key to reducing child mortality. There is currently an ongoing multi-center trial in Uganda and Malawi that we hope will shed light into establishing best transfusion and treatment strategies in preventing mortality for children with anemia [28].

The prevalence of very severe anemia was found to be high among Tanzanian children who were hospitalized. In our study, nearly 20% of the children were found to have very severe anemia, and 40% of children had severe anemia or very severe anemia. The high prevalence of anemia appears to be consistent with a prior study done at our institution [29]. A possible explanation may be due to the high prevalence of malaria, sickle cell disease, soil transmitted helminths and nutritional deficiencies in our region [30–32]. By comparison to the general community or household level, the prevalence of severe anemia has been reported to be as high as 2.5% in East Africa and 3.4% in sub-Saharan Africa [33–34]. The high prevalence of anemia, whether for children hospitalized or in the community, highlights the continual need to make identification and treatment of anemia a public health priority.

Our study has limitations. We did not acquire a hemoglobin level at time of discharge. Also, due to lack of resources at both hospitals’ diagnostic facilities, we were unable to consistently obtain tests like a full blood count with red blood cell indices, blood smears, or iron studies that could give us insight to determine causes of anemia at the time of our study. Another limitation was the inability to perform autopsies for in-hospital deaths, and verbal autopsies for post-hospital deaths to determine cause of death. We also had a higher lost to follow-up rate for children with very severe anemia. Children lost to follow-up may have been more likely to have died. This would make our findings underestimate the true risk that very severe anemia has on mortality.

In conclusion, we conducted a prospective cohort study of 505 children up to 12 years of age hospitalized with very severe anemia and followed for one year post-hospitalization in Tanzania. Nearly 30% of children hospitalized with very severe anemia died within one year. More than half of those deaths occurring after hospital discharge. Since anemia is extremely prevalent among both young and older African children, and the consequences of very severe anemia so deadly, prevention and treatment of anemia must be a high public health priority to reduce child mortality in Africa.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the children and their caretakers involved in this study, the clinicians and nurses who cared for the children, and faculty in the Department of Pediatrics of BMC and STH.

Data Availability

Data are available from figshare, DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.6931286.

Funding Statement

Funding was provided by a pilot award from the Weill Cornell Medical College Department of Pediatrics [#87000213] to DH. NK is supported by a grant Medical Education Partnership Initiative Junior Faculty [#D43TW010138]. PM is supported by a grant from Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award [UL 1TR002541]). RP is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health [#K01 TW010281]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Bojang KA, Van Hensbroek MB, Palmer A, Banya WA, Jaffar S, Greenwood BM. Predictors of mortality in Gambian children with severe malaria anaemia. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1997; 17: 355–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calis JC, Phiri KS, Faragher EB, Brabin BJ, Bates I, Cuevas LE, et al. Severe anemia in Malawian children. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 888–899. 10.1056/NEJMoa072727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.English M, Ahmed M, Ngando C, Berkley J, Ross A. Blood transfusion for severe anaemia in children in a Kenyan hospital. Lancet 2002; 359: 494–495. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07666-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiguli S, Maitland K, George EC, Olupot-Olupot P, Opoka RO, Engoru C, et al. Anaemia and blood transfusion in African children presenting to hospital with severe febrile illness. BMC Med 2015; 13: 21 10.1186/s12916-014-0246-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koram KA, Owusu-Agyei S, Utz G, Binka FN, Baird JK, Hoffman SL, et al. Severe anemia in young children after high and low malaria transmission seasons in the Kassena-Nankana district of northern Ghana. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2000; 62: 670–674. 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lackritz EM, Campbell CC, Ruebush TK II, Hightower AW, Wakube W, Steketee RW, et al. Effect of blood transfusion on survival among children in a Kenyan hospital. Lancet 1992; 340: 524–528. 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91719-o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marsh K, Forster D, Waruiru C, Mwangi I, Winstanley M, Marsh V, et al. Indicators of life-threatening malaria in African children. N Engl J Med. 1995; 332: 1399–1404. 10.1056/NEJM199505253322102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newton CR, Warn PA, Winstanley PA, Peshu N, Snow RW, Pasvol G, et al. Severe anaemia in children living in a malaria endemic area of Kenya. Trop Med Int Health 1997; 2: 165–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phiri KS, Calis JCJ, Faragher B, Nkhoma E, Ng’oma K, Mangochi B, et al. Long term outcome of severe anaemia in Malawian children. PLoS ONE 2008; 3: e2903 10.1371/journal.pone.0002903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiens MO, Pawluk S, Kissoon N, Kumbakumba E, Ansermino JM, Singer J, et al. Pediatric Post-Discharge Mortality in Resource Poor Countries: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2013; 8: e66698 10.1371/journal.pone.0066698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hau DK, Chami N, Duncan A, Smart LR, Hokororo A, Kayange NM, et al. Post-hospital mortality in children aged 2–12 years in Tanzania: A prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 2018; 8: e0202334 10.1371/journal.pone.0202334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. WHO STEPS Instrument. Geneva, Switzerland; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes. KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int 2013;3:43–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National AIDS Control Programme (NACP). National Guidelines for the Management of HIV and AIDS, 4th ed. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: The United Republic of Tanzania Ministry of Health & Social Welfare; 2012.

- 15.World Health Organization. Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System. Geneva, Switzerland; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10 Revision. Geneva, Switzerland; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masquelier B, Hug L, Sharrow D, You D, Hogan D, Hill K, et al. Global, regional, and national mortality trends in older children and young adolescents (5–14 years) from 1990 to 2016: an analysis of empirical data. Lancet Glob Health. 2018; 6: e1087–1099. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30353-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patton GC, Azzopardi P. Missing in the middle: measuring a million deaths annually in children aged 5–14 years. Lancet Glob Health. 2018; 6: e1048–1049. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30417-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Islam MA, Rahman MM, Mahalanabis D, Rahman AK. Death in a diarrhoeal cohort of infants and young children soon after discharge from hospital: risk factors and causes by verbal autopsy. J Trop Pediatr 1996; 42: 342–347. 10.1093/tropej/42.6.342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roy SK, Chowdhury AK, Rahaman MM. Excess mortality among children discharged from hospital after treatment for diarrhoea in rural Bangladesh. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1983; 287: 1097–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veirum JE, Sodeman M, Biai S, Hedegard K, Aaby P. Increased mortality in the year following discharge from a paediatric ward in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau. Acta Paediatr 2007; 96: 1832–1838. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00562.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zucker JR, Lackritz EM, Ruebush TK, Hightower AW, Adungosi JE, Were JB, et al. Childhood Mortality During and After Hospitalization in Western Kenya: Effect of Malaria Treatment Regimens. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1996; 55: 655–660. 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.55.655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome—an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 100–102. 10.1056/NEJMp1212324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.English L, Kumbakumba E, Larson CP, Kabakyenga J, Singer J, Kissoon N, et al. Pediatric out-of-hospital deaths following hospital discharge: a mixed-methods study. Afr Health Sci 2016; 16: 883–891. 10.4314/ahs.v16i4.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kagabo DM, Kirk CM, Bakundukize B, Hedt-Gauthier BL, Gupta N, Hirschhorn LR, et al. Care-seeking patterns among families that experienced under-five child mortality in rural Rwanda. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0190739 10.1371/journal.pone.0190739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdullahi AA. Trends and Challenges of Traditional Medicine in Africa. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med 2011; 8: 115–123. 10.4314/ajtcam.v8i5S.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scott SP, Chen-Edinboro LP, Caulfield LE, Murray-Kolb LE. The impact of anemia on child mortality: an updated review. Nutrients 2014; 6: 5915–5932. 10.3390/nu6125915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.BioMed Central. Transfusion and Treatment of severe anaemia in African children (TRACT): a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial [Internet]. London: BioMed Central; 2015 [cited 2018 Sept 17]. https://trialsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13063-015-1112-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Simbauranga RH, Kamugisha E, Hokororo A, Kidenya BR, Makani J. Prevalence and factors associated with severe anaemia amongst under-five children hospitalized at Bugando Medical Centre, Mwanza, Tanzania. BMC Hematol 2015; 15: 13 10.1186/s12878-015-0033-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smart LR, Orgenes N, Mazigo HD, Minde M, Hokororo A, Shakir M, et al. Malaria and HIV among pediatric inpatients in two Tanzanian referral hospitals: a prospective study. Acta tropica 2016; 159: 36–43. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ambrose EE, Makani J, Chami N, Masoza T, Kabyemera R, Peck RN, et al. High birth prevalence of sickle cell disease in Northwestern Tanzania. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2018; 65: e26735 10.1002/pbc.26735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmed MM, Hokororo A, Kidenya BR, Kabyemera R, Kamugisha E. Prevalence of undernutrition and risk factors of severe undernutrition among children admitted to Bugando Medical Centre in Mwanza, Tanzania. BMC Nutrition 2016; 2: 49 10.1186/s40795-016-0090-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stevens GA, Finucane MM, De-Regil LM, Paciorek CJ, Flaxman SR, Branca F, et al. Global, regional, and national trends in haemoglobin concentration and prevalence of total and severe anaemia in children and pregnant and non-pregnant women for 1995–2011: a systematic analysis of population-representative data. The Lancet Global Health 2013; 1: e16–25. 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70001-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moschovis PP, Wiens MO, Arlington L, Antsygina O, Hayden D, Dzik W, et al. Individual, maternal and household risk factors for anaemia among young children in sub-Saharan Africa: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018; 8: e019654 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from figshare, DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.6931286.