Abstract

Background

Heart surgery is a major stressful event that can have a significant negative effect on patients’ quality of life (QoL) and may cause long-term posttraumatic stress reactions. The aim of this pilot study was to estimate the longitudinal change and predictors of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) dynamics and identify factors associated with PTS at 5-year follow-up (T2) after elective cardiac surgery and associations with pre-surgery (T1) QoL.

Materials and methods

Single-centre prospective study was conducted after Regional Bioethics Committee approval. Adult consecutive patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery were included. HRQOL was measured using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) questionnaire before (T1) and 5-years after (T2) cardiac surgery. Posttraumatic stress was assessed using the International Trauma Questionnaire.

Results

The pilot study revealed a significant positive change at 5-year follow-up in several domains of SF-36: physical functioning (PF), energy/fatigue (E/F), and social functioning (SF). Prolonged postoperative hospital stay was associated with change in SF (p < 0.01), E/F (p < 0.05) and emotional well-being (p < 0.05). The percentage of patients that had the posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) at T2 was 12.2%. Posttraumatic stress symptoms were associated with longer hospitalization after surgery (p < 0.01).

Conclusions

HRQOL improved from baseline to five years postoperatively. Patients with lower preoperative HRQOL scores tended to have a more significant improvement of HRQOL five years after surgery. A prolonged postoperative hospital stay had a negative impact on postoperative social functioning, energy/fatigue, and emotional well-being. Increased levels of PTSD were found in cardiac surgery patients following five years after the surgery.

Keywords: cardiac surgery, health-related quality of life, posttraumatic stress

Abstract

ILGALAIKIAI GYVENIMO KOKYBĖS POKYČIAI IR PATIRIAMO STRESO REAKCIJOS PO PLANINIŲ ŠIRDIES OPERACIJŲ: PRELIMINARŪS REZULTATAI PRAĖJUS PENKERIEMS METAMS PO OPERACIJOS

Santrauka

Įvadas. Širdies operacija, kaip didelį stresą kelianti gyvenimo situacija, gali turėti reikšmingą neigiamą įtaką pacientų gyvenimo kokybei ir sukelti ilgalaikes patiriamo streso reakcijas.

Tyrimo tikslas. Įvertinti ilgalaikius gyvenimo kokybės pokyčius, nustatyti patiriamo streso reakcijų rizikos veiksnius ir jų sąsajas su priešoperacine gyvenimo kokybe praėjus penkeriems metams po planinės širdies operacijos.

Darbo objektas ir metodai. Perspektyvinis pilotinis tyrimas buvo atliktas gavus Vilniaus regioninio biomedicininių tyrimų etikos komiteto leidimą. Į tyrimą buvo įtraukti suaugę pacientai, kuriems planuojama širdies operacija. Gyvenimo kokybės pokyčiai buvo vertinami naudojant SF-36 klausimyną, pacientai apklausti prieš širdies operaciją ir praėjus penkeriems metams po jos. Patiriamas stresas buvo vertinamas naudojant tarptautinį traumos klausimyną.

Rezultatai. Pilotinis tyrimas nustatė itin didelius teigiamus SF-36 klausimyno pokyčius fizinio aktyvumo, energingumo / gyvybingumo ir socialinės funkcijos srityse praėjus penkeriems metams po širdies operacijos. Pailgėjusi gulėjimo ligoninėje po širdies operacijos trukmė buvo susijusi su socialinės funkcijos (p < 0,01), energingumo / gyvybingumo (p < 0,05) ir emocinės būsenos (p < 0,05) pokyčiais. Praėjus penkeriems metams po širdies operacijos 12,2 % pacientų susidūrė su padidėjusia rizika potrauminio streso sutrikimui išsivystyti. Patiriamo streso simptomai buvo susiję su pailgėjusia hospitalizacijos trukme po širdies operacijos (p < 0,01).

Išvados. Su sveikata susijusi gyvenimo kokybė per penkerius metus po širdies operacijos pagerėjo, ypač mažesnės priešoperacinės gyvenimo kokybės pacientų grupėje. Pailgėjusi gulėjimo ligoninėje po širdies operacijos trukmė turėjo neigiamą įtaką pooperacinei socialinei funkcijai, energingumui / gyvybingumui ir emocinei būsenai.

Praėjus penkeriems metams po širdies operacijos pacientams buvo nustatyta padidėjusi potrauminio streso sutrikimo išsivystymo rizika.

Raktažodžiai: širdies operacija, su sveikata susijusi gyvenimo kokybė, patiriamas stresas / potrauminis stresas

INTRODUCTION

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) not only captures the functional impact of illness but also reflects overall patient satisfaction with the procedure or treatment. Heart surgery is a major stressful event that can have a significant negative effect on patients’ quality of life (QoL) (1, 2) and may cause long-term posttraumatic stress reactions and increased risk for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (2, 3).

We present preliminary findings of broader research aimed at estimating the longitudinal change and predictors of HRQOL dynamics and identifying factors associated with PTS at 5-year follow-up (T2) after elective cardiac surgery and associations with pre-surgery (T1) QoL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants. Single-centre prospective pilot study was conducted after Regional Bioethics Committee approval. In total, 41 adults, 13 females (31.7%) and 28 males (68.3%), consecutive patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery from March to May of 2013 were included in data analysis. Three types of heart surgery were performed: coronary artery bypass grafting, valve surgery, and combined surgery. The age of the participants ranged from 37 to 89 years, with a mean age of 67.38 ± 10.39 at 5-year follow-up (T2).

Measures. Cardiac operative risk was evaluated using Euroscore II (European system for cardiac operative risk evaluation) (4–5). The length of ICU and postoperative hospital stay were recorded for each participant.

HRQOL was measured using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) questionnaire before (T1) and 5-years after (T2) cardiac surgery (6). Quality of life was assessed in six domain subscales: physical functioning, energy/fatigue, emotional well-being, social functioning, pain, and general health.

PTSD symptoms were assessed using the International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) (7–8) with the index trauma heart surgery at T2. We estimated three core PTSD symptoms: re-experiencing, avoidance, and sense of threat. High risk for PTSD was identified in patients with at least of two clinically significant core PTSD symptoms.

Data analysis. Statistical data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics v. 23.0. Paired sample t-test was used for comparisons of data at T1 and T2. Cohen’s d was used to estimate within group effect sizes. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Pre-surgery mean EuroSCORE II value at T1 was 1.72% ± 0.97. Majority of patients (61%, n = 25) underwent coronary artery bypass grafting, 29.3% (n = 12) valve surgery, and 9.8% (n = 4) combined surgery. Mean ICU stay was 2 ± 1.4 days, postoperative hospital stay – 13 ± 4.9 days and ranged from 7 to 30 days. Patients’ baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics (N = 41)

| Variable | N (%) / Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Demographical data | N = 41 |

| Sex, males Age, years |

28 (68.3%) 67.38 ± 10.39 |

| Operative risk | |

| EuroSCORE II | 1.72% ± 0.97 |

| Operation type | |

| CABG Valve surgery Combined surgery |

25 (61%) 12 (29.3%) 4 (9.8%) |

| Length of hospital stay | |

| ICU stay, days Postoperative hospital stay, days |

2 ± 1.4 13 ± 4.9 |

SD – standard deviation; Euroscore II = European system for cardiac operative risk evaluation; CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting.

Pilot study revealed significant positive change at 5-year follow-up in several domains of SF-36: physical functioning (PF), energy/fatigue (E/F), and social functioning (SF). HRQOL dynamics pre-surgery and at 5-year follow-up is well demonstrated in Table 2. The PF change significantly correlated with baseline SF (r = –0.34, p < 0.05). Change of emotional well-being (E/W) and E/F at five year follow-up was associated with the same dimensions preoperatively (r = –0.71, p < 0.001) and, respectively (r = –0.63, p < 0.001). Prolonged postoperative hospital stay was associated with a change in SF (r = 0.35, p < 0.01), E/F (r = –0.35, p < 0.05), and E/W (r = –0.39, p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Quality of life pre-surgery and at 5-year follow-up (N = 41)

| SF-36 subscales | Pre-surgery M (SD) | 5-year follow-up M (SD) | t-test | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | 54.51 (23.92) | 74.15 (27.77) | –5.28 *** | 0.76 |

| Energy/fatigue | 55.90 (15.47) | 62.31 (14.36) | –2.26 * | 0.43 |

| Emotional well-being | 59.79 (19.33) | 65.13 (16.36) | –1.47 | 0.29 |

| Social functioning | 62.50 (29.84) | 77.49 (28.85) | –2.47 * | 0.51 |

| Pain | 50.92 (24.91) | 61.57 (32.03) | –1.86 | 0.37 |

| General health | 50.00 (16.34) | 33.21 (15.15) | 6.09 *** | 1.09 |

SF-36 – Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey.

* p < 0.05;

*** p < 0.001.

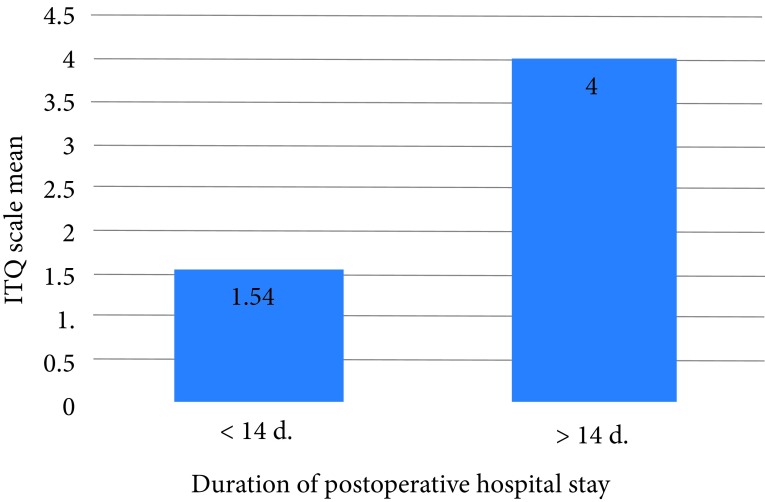

High levels of PTSD symptoms were found in the sample of cardiac surgery patients following five years after the surgery. About one of eight patients (12.2%, n = 5) had the risk of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) at T2. PTSD symptoms were associated with longer hospitalization after surgery (r = 0.45, p < 0.01). The correlation between higher ITQ scale values/PTS symptoms and prolonged postoperative hospital stay is shown in Figure. Furthermore, we found that PTSD symptoms at T2 were associated with SF-36 pain domain at T1 (r = 0.33, p < 0.05). We did not find an association with PTSD symptoms and other SF-36 domains.

DISCUSSION

Health-related quality of life is a multidimensional concept covering self-perceived mental, emotional, and physical health alongside with social well-being. Post-procedural outcomes are frequently evaluated from deficit – mortality and morbidity aspect. However, over the last decades patient-centred care is evolving and HRQOL has become an important component of public health surveillance and outcome analysis (9). Aging population and increased incidence of chronic co-morbidities raise the question whether complex cardiac surgical treatment brings an improvement of health related quality of life and what the main factors associated with decline of self-perceived well-being are.

Figure.

PTSD symptoms and duration of the post-operative hospital stay

ITQ – International Trauma Questionnaire

Preliminary data from our pilot study confirmed that five years after cardiac surgery, the majority of the patients noted overall improvement in all HRQOL domains except General Health (10–12). These findings are similar to other authors’ findings and might be related to overall aging of the patients (13–15). Patients with lower preoperative HRQOL tended to achieve a significant improvement of self-perceived health postoperatively. On the other hand, patients with satisfactory levels of health, not limiting their social well-being preoperatively, improved less. Reduced postoperative mobility, pain, the loss of social interactions and prolonged rehabilitation could result in a possible mismatch of expected and perceived postoperative recovery (16). These findings are supported by recent research. Psy-Heart trail researchers (17) indicated the importance of managing and optimizing patient expectations before the heart surgery. Analysis of factors associated with deterioration of HRQOL postoperatively revealed that a prolonged postoperative hospital stay had a negative impact on long-term quality of life – social functioning and emotional well-being, that could be related with a post-traumatic stress disorder or a more complex postoperative course (2, 18).

Our study has limitation associated with a small sample size. A larger patient group is needed to draw conclusions about the multifactorial nature of long-term postoperative well-being. Perioperative psychological interventions providing emotional support and general advice to patients undergoing complex surgical procedures are needed to control patients’ expectations and increase overall satisfaction with achieved treatment result.

CONCLUSIONS

Preliminary findings showed that HRQOL improved from baseline to five years postoperatively. Patients with lower preoperative HRQOL scores tended to have a more significant improvement of HRQOL five years after surgery. Prolonged postoperative hospital stay had a negative impact on postoperative social functioning, energy/fatigue, and emotional well-being. Our pilot study indicated increased levels of PTSD in a sample of cardiac surgery patients following five years after surgery.

Further data analysis and inclusion of a larger patient group are needed to confirm pilot findings and to explore the longitudinal change and long-term predictors of HRQOL dynamics and PTSD after cardiac surgery.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

Daiva Gražulytė, Evaldas Kazlauskas, Ieva Norkienė, Smiltė Kolevinskaitė, Greta Kezytė, Indrė Urbanavičiūtė, Akvilė Sabestinaitė, Gintarė Korsakaitė, Paulina Želvienė, Donata Ringaitienė, Gintarė Šostakaitė, Jūratė Šipylaitė

References

- Maillard J, Elia N, Haller CS, Delhumeau C, Walder B. Preoperative and early postoperative quality of life after major surgery – a prospective observational study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015. February 4; 13: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll C Schelling G Goetz AE Kilger E Bayer A Kapfhammer H-P et al. . Health-related quality of life and post-traumatic stress disorder in patients after cardiac surgery and intensive care treatment. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000. September; 120(3): 505–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porhomayon J, Kolesnikov S, Nader ND. The impact of stress hormones on post-traumatic stress disorders symptoms and memory in cardiac surgery patients. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2014; 6(2): 79–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashef SAM Roques F Sharples LD Nilsson J Goldstone CSAR et al. . EuroSCORE II. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012. April; 41(4): 734–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers J, Pullan M, Fabri B, McShane J, Shaw M, Mediratta N, Poullis M. Validation of EuroSCORE II in a modern cohort of patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013. April; 43(4): 688–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tully PJ. Quality-of-life measures for cardiac surgery practice and research: a review and primer. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2013. March; 45(1): 8–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karatzias T Cloitre M Maercker A Kazlauskas E Shevlin M Hyland P et al. . PTSD and Complex PTSD: ICD-11 updates on concept and measurement in the UK, USA, Germany and Lithuania. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2017; 8(sup 7): 1418103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazlauskas E, Gegieckaite G, Hyland P, Zelviene P, Cloitre M. The structure of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD in Lithuanian mental health services. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2018; 9: 1414559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norkiene I, Urbanaviciute I, Kezyte G, Vicka V, Jovaisa T. Impact of pre-operative health related quality of life on outcomes after heart surgery. ANZ J Surg. 2018. April; 88(4): 332–336.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taghipour HR Naseri MH Safiarian R Dadjoo Y Pishgoo B Mohebbi HA et al. . Quality of life one year after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2011. March; 13(3): 171–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurfirst V Mokráček A Krupauerová M Čanádyová J Bulava A Pešl L et al. . Health-related quality of life after cardiac surgery – the effects of age, preoperative conditions and postoperative complications. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014; 9: 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjeilo KH, Wahba A, Klepstad P, Lydersen S, Stenseth R. Survival and quality of life in an elderly cardiac surgery population: 5-year follow-up. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013. September; 44(3): e182–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullogh ME, Laurenceau J-P. Gender and the natural history of self-rated health: a 59-year longitudinal study. Health Psychology. 2004; 23(6): 651–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J Shaw BA Krause N Bennett JM Kobayashi E, Fukaya T et al. . How does self-assessed health change with age? A study of older adults in Japan. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc. Sci 2005; 60B(4): S224–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehr P, Patrick DL. Trajectories of health for older adults over time: Accounting fully for death. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2003; 139: 416–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourassa-Moreau É, Labelle H Parent S Hresko MT Sucato D Lenke LG et al. . Expectations for postoperative improvement in health-related quality of life in young patients with lumbosacral spondylolisthesis: a prospective cohort study. 2019. February 1; 44(3): E181–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rief W Shedden-Mora MC Laferton JA Auer C Petrie KJ Salzmann S et al. . Preoperative optimization of patient expectations improves long-term outcome in heart surgery patients: results of the randomized controlled PSY-HEART trial. BMC Med. 2017. January 10; 15(1): 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudino M Girola F Piscitelli M Martinelli L Anselmi A Della Vella C et al. . Long-term survival and quality of life of patients with prolonged postoperative intensive care unit stay: Unmasking an apparent success. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007. August; 134(2): 465–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]