Abstract

Physical safety is a primary concern among homeless youth because they struggle to secure basic necessities and a permanent place to live. Despite this, studies have not fully examined the numerous linkages that might explain risk for victimization within the context of material insecurity. In this study, we examine multiple levels of both proximal and distal risk factors at the individual (e.g. mental health), family (e.g. child abuse), and environmental levels (e.g. finding necessities) and their associations with physical and sexual street victimization among 150 Midwestern homeless youth. Results from path analyses show that child physical abuse is positively associated with anxiety, depressive symptoms, locating necessities, and street physical victimization. Having difficulties finding basic necessities is positively correlated with street physical victimization. Experiencing child sexual abuse is positively associated with street sexual victimization. Additionally, sleeping at certain locations (e.g. violence shelter, in a car) is associated with less sexual street victimization compared to temporarily staying with a family member. These findings have implications for service providers working to improve the safety and well-being of homeless youth.

Keywords: Child abuse, Mental health, Sleeping arrangements, Street victimization, Homeless

An estimated 2.5 million children experience homelessness on a yearly basis in the United States (National Center on Family Homelessness, 2014). The living situation of these young people is perilous. Without a permanent place to live, many homeless youths resort to couch surfing (i.e. sleeping at a friend’s place), staying at a youth shelter, or other places not intended as a permanent domicile (Tyler, Akinyemi, & Kort-Butler, 2012). This residential instability calls into question youths’ safety in their everyday lives if their options for housing are severely constrained by economic resources (Lee, Tyler, & Wright, 2010). Subsequently, many homeless youths are vulnerable to experiencing sexual and physical victimization while on the street when they do not have a secure, reliable source of shelter (Bender, Brown, Thompson, Ferguson, & Langenderfer, 2015).

Though some research has examined certain risk factors for victimization among homeless youth, such as child abuse and mental health challenges (Bender et al., 2015; Tyler, Whitbeck, Hoyt, & Cauce, 2004; Tyler & Beal, 2010), no studies have yet examined both proximal and distal risk factors at the individual (e.g. mental health), family (e.g. child abuse), and environmental levels (e.g. finding necessities and past night sleeping arrangements) and their associations with physical and sexual street victimization. Holistically delineating these linkages is crucial because understanding how various levels of influence are interrelated provides a more comprehensive understanding of the complex victimization process, and thus may underscore key intervention possibilities. Furthermore, youth experiencing homelessness are intricately shaped by multiple influential factors spanning their life, including their family background, mental health and current living situation, so it is necessary to examine these variables simultaneously as they all continue to impact youths’ outcomes. The current study fills this theoretical and empirical gap by implementing a life stress framework (Lin & Ensel, 1989; Pearlin, 1989) to examine the multifaceted connections between proximal and distal risk factors with sexual and physical victimization at the individual, family and environmental levels among a group of homeless youth in the United States. Understanding the various life stress linkages that may place these youth at heightened risk for street victimization is key to providing service interventions for this vulnerable population that foster youths’ sense of personal security and well-being.

Early Life Histories of Homeless Youth Prior to Running Away

A considerable number of homeless youths have experienced child abuse in their families of origin prior to running away: approximately 50% are victims of child physical abuse (Rattelade, Farrell, Aubry, & Klodawsky, 2014), and between 25% and 33% are victims of child sexual abuse (Bender et al., 2015). In addition to high rates of child abuse, many homeless youths have a history of running away from home multiple times (Tyler, Hoyt, Whitbeck, & Cauce, 2001), which likely negatively impacts their mental health and increases their chances for repeat victimization experiences (Harris, Rice, Rhoades, Winetrobe, & Wenzel, 2017). Not only do many of these young people endure hazardous conditions at home, but their personal safety is further threatened when they enter into homelessness.

Mental Health and Victimization While on the Street

In addition to adverse early life histories prior to leaving home, homeless youth also experience disproportionally high rates of victimization while on the street: between 21% and 32% of homeless youth report being sexually victimized while on the street and over 50% of homeless young people report one or more occurrences of being physically victimized (Bender et al., 2015), such as being robbed or beaten up (Tyler & Beal, 2010). Those who experience more depressive symptoms (Bender et al., 2015), more anxiety (Tyler, Schmitz, & Ray, 2017), and more physical street victimization (Tyler & Melander, 2015) are more likely to report a history of child physical abuse. Poorer mental health (Rattelade et al., 2014), and being sexually victimized on the street (Tyler & Melander, 2015) are also associated with a history of child sexual abuse. Moreover, research finds that homeless youth are at elevated risk for experiencing re-victimization (Harris et al., 2017). Finally, experiencing more anxiety, more depressive symptoms (Tyler et al., 2017), and more street victimization (Kort-Butler, Tyler, & Melander, 2011; Tyler et al., 2017) has been associated with running away more often. This can become a problematic cycle as research indicates that victimization can lead to further depression and other negative mental health outcomes among homeless youth (Bender, Ferguson, Thompson, & Langenderfer, 2014). A history of child abuse coupled with a current, precarious living situation threatens young people’s well-being and ability to remain safe.

Sleeping Arrangements

Homeless youth, by definition, lack a permanent place to live. Most research that has examined where youth sleep has typically focused on homeless youths’ shelter use, though the time frame used varies, which may account for the significant range found in studies. For example, Carlson, Sugano, Millstein, and Auerswald (2006) found that only 7% of homeless youth reported shelter use in the past three months, whereas Tyler et al. (2012) found the percentage to be 27% when youth were asked about shelter use for the past year. Kort-Butler & Tyler (2012), meanwhile, found the past year rate of shelter use to be 55%. Though shelter use increases the likelihood that homeless youth will connect with other services (Ha, Narendorf, Santa Maria, & Bezette-Flores, 2015), a significant number of homeless youth do not utilize shelters, while others do not access any services at all (Tyler et al., 2012), and thus may have trouble finding basic necessities (e.g. food and shelter). Reasons for non-use or lower service use include feelings of stigma and shame and lack of knowledge about services or a desire to be self-reliant (Ha et al., 2015). Having a negative experience with a staff member is another obstacle to seeking services among homeless youth (Solorio, Milburn, Andersen, Trifskin, & Rodrigues, 2006).

For homeless youth not staying in shelters, other options for temporary places to sleep can include couch surfing, staying on the street, in a car, or in a transitional living facility. Because homeless youth lack a permanent place to sleep, it is often difficult for them to protect themselves (Lee et al., 2010); thus, physical safety is a primary concern. It is possible that certain sleeping arrangements are more protective than others and therefore may be associated with a lower risk for victimization. At present, however, little is known about how youths’ temporary sleeping arrangements on the previous night impact their vulnerability to street victimization. To address this gap, we examine youths’ early family histories, mental health challenges and a snapshot of youths’ sleeping arrangements on the previous night to begin delineating how diverse life experiences and various sources of shelter may shape victimization processes.

Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

We use a life stress framework (Lin & Ensel, 1989; Pearlin, 1989), which emphasizes multiple levels of risk factors at the individual, family, and environmental levels. This framework also considers variables that are both distal (occurring in the past) as well as more proximal (occurring more recently), which has the benefit of providing a more complete understanding of formative life processes within the context of material hardship. Applied to the current study, all three levels are fundamental to understanding the relationship among child abuse, locating necessities, mental health, previous night sleeping arrangements and street victimization among homeless youth. Additionally, the life stress framework assumes that individuals who are exposed to one serious stressor (e.g. child sexual abuse) will also be exposed to additional stressors (e.g. repeat victimization), which can then cluster together (Pearlin, 1989). Moreover, this framework holds that stressors can be both distal events, such as child abuse, or more proximal events, such as where youth slept the previous night, and obtaining basic necessities. Both types of factors should be taken into account when examining the life stressors that young people encounter as their early and more recent experiences combine to shape their outcomes. Thus, according to a life stress framework, examining both distal and proximal factors, as well as multiple levels of influence, are necessary to gain a more holistic understanding of street victimization and determine appropriate intervention opportunities. As such, we hypothesized the following: Hypothesis #1: both childhood abuse and the frequency with which youth report having run away from home will be associated with poorer outcomes, including more trouble finding basic necessities, increased mental health challenges, and higher rates of victimization. Hypothesis #2: Certain sleeping arrangements will be associated with higher rates of victimization. The models control for gender as females tend to have poorer mental health than males (Afifi et al., 2008), and research finds differential risk for street victimization by gender (Tyler & Beal, 2010).

Materials and Methods

One hundred fifty youth were interviewed in shelters and on the streets from July 2014 to October 2015 in two Midwestern cities. Selection criteria required participants to be between the ages of 16 and 22 (i.e. the age range of youth that participating agencies serve) and meet the definition of runaway or homeless. Runaway refers to youth under age 18 who have spent the previous night away from home without the permission of parents or guardians (Ennett, Bailey, & Federman, 1999). Homeless youth, as inclusively defined by the 2015 reauthorization of the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, includes those who lack permanent housing such as having spent the previous night with a stranger, in a shelter or public place, on the street, staying with friends, staying in a transitional living facility, or other places not intended as a permanent domicile (National Center for Homeless Education & National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth, 2017).

Four trained and experienced interviewers conducted the interviews (two in each city). Interviewers approached youth at shelters, food programs and during street outreach. Interviewers varied the times of the day that they went to these locations, on both weekdays and weekends. This sampling protocol was conducted repeatedly over the course of the study. Informed consent was obtained from all participants who were informed that they would need to complete all three parts of the study if they agreed to participate (i.e. baseline structured interview, 30 days of text messaging and a follow-up structured interview). Full details of these study parts are reported elsewhere (Tyler & Olson, 2018). We report findings from the first part of the study, a baseline structured interview, which lasted 45 minutes and for which participants received a $20 gift card for completing. Referrals for shelter, counseling services, and foods ervices were offered to all youth regardless of their decision to participate. Less than 3% of youth (N = 5) refused to participate or were ineligible. The university Institutional Review Board at the first author’s institution approved this study.

Measures

Independent Variables

Respondent gender was coded 0 = male and 1 = female and used as a control variable. Number of times run was a single item that asked youth for the total number of times that they had ever run away or left home (adapted from Whitbeck & Simons, 1990).

Child physical abuse included 16 items from the Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore, & Runyan, 1998). Youth were asked, for example, how frequently their caretaker shook them or kicked them hard (0 = never to 6 = more than 20 times). A mean scale was created where a higher score indicated more physical abuse. Cronbach’s alpha was .93.

Child sexual abuse included seven items (adapted from Whitbeck & Simons, 1990) that asked youth, how often has any adult or someone at least five years older than you asked you, for example, to do something sexual or had you touch them sexually (0 = never to 6 = more than 20 times). Due to skewness, the seven items were dichotomized (0 = never and 1 = at least once) and then a count variable was created where a higher score equaled a greater number of different types of sexual abuse experienced. Cronbach’s alpha was .92. These same items have been used in previous studies with homeless young people (Whitbeck & Simons, 1990; α = .93; Tyler & Melander, 2015; α = .88).

Trouble finding basic necessities included four items created by the first author. Youth were asked, “since leaving home and being on your own, how often do you have trouble finding,” ‘food,’ ‘a place to stay,’ ‘money for something that you really need,’ and ‘clothing or other basic essentials (e.g. toiletries or blankets) (0 = never to 4 = every day). Cronbach’s alpha was .86. Due to skewness, each item was dichotomized (0 = never and 1 = at least 1–2 days per week) and then summed, where a higher score indicated a greater number of necessities that youth had trouble finding.

Depressive symptoms included 10 items from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977). The CES-D, which requires respondents to reflect upon their experiences during the past week, includes items such as “I was bothered by things that don’t usually bother me” and “I had trouble keeping my mind on what I was doing” (0 = never to 3 = 5–7 days). Certain items were reverse coded and then a mean scale was created where higher scores indicated more depressive symptomology. Cronbach’s alpha was .79. A similar scale has been used with homeless youth (Bao, Whitbeck, & Hoyt, 2000; α = .89).

Anxiety included 10 items from the Endler Multi-dimensional Anxiety Scale-State (Endler, Parker, Bagby, & Cox, 1991), such as “I fear defeat” and “I am unable to focus on a task” (1 = not at all true to 5 = completely true). A mean scale was created so that higher scores indicated more anxiety. Cronbach’s alpha was .88.

Sleeping arrangements was an open-ended question that asked respondents where they slept last night. These open-ended responses were coded into six dummy variables, which included: (1) couch surfing, (2) youth shelter, (3) transitional living facility, (4) adult shelter (ages 19 and older), (5) family member (used as the omitted category in the analyses), and (6) other location, which combined “outside,” “in their car,” “someone’s house,” “maternity group home,” “violence shelter,” and “romantic partners’ house,” due to small numbers in each of these categories.

Dependent Variables

Physical street victimization included six items such as “how often were you beaten up” and “how often were you robbed” since leaving home (0 = never to 3 = many times). A mean scale was created where higher scores indicated greater street physical victimization. Cronbach’s alpha was .85. These same items have been used in previous studies with homeless youth (Whitbeck & Simons, 1990; α = .82).

Sexual street victimization included four items such as how often were you “touched sexually when you didn’t want to be” and “forced to do something sexual” since leaving home (0 = never to 3 = many times). Cronbach’s alpha was .90. Due to skewness, the individual items were dichotomized (0 = never and 1 = at least once) and then a count variable was created where a higher score indicated a greater number of different types of sexual victimization experienced (Tyler & Beal, 2010; α = .83).

Data Analytic Strategy

We estimated two fully recursive path models for our two outcome variables: physical and sexual street victimization, using the maximum likelihood estimator in Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2015). Both these models examine distal and proximal variables in the lives of homeless youth at the individual, family and environmental levels based on a life stress framework. We report standardized beta coefficients in both Figures. A p-value of less than or equal to .05 is considered significant.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

We interviewed 150 homeless youth; one-half (51%) were female. Ages ranged from 16 to 22 years (M = 19.4 years). Regarding race/ethnicity, 41.3% were White, 26% Black or African American, 10% Hispanic or Latino, 4% American Indian or Alaskan Native, 13.3% bi-racial and 5.3% multi-racial. All but two youth (less than 2%) had experienced child physical abuse at least once, while 41% experienced one or more types of child sexual abuse. Youth reported running away from home between one and 35 times and only 17% of youth reported having no trouble finding basic necessities. See Table 1 for a list of descriptive information for all study variables.

Table 1.

Descriptives for All Study Variables (N = 150)

| N (%) | ||

| Dichotomous Variables | ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 77 (51%) | |

| Male | 73 (49%) | |

| Sleeping Arrangements | ||

| Couch surfing | 37 (25%) | |

| Youth shelter | 16 (11%) | |

| Transitional living facility | 41 (27%) | |

| Other location | 25 (17%) | |

| Family member | 13 (9%) | |

| Adult shelter | 13 (9%) | |

| Continuous Variables | M (SD) | Range |

| Child Abuse | ||

| Child physical abuse | 2.16 (1.38) | 0–5.63 |

| Child sexual abuse | 1.53 (2.29) | 0–7 |

| Housing Instability | ||

| Number of times run | 4.9 (6.32) | 0–35 |

| Trouble finding necessities | 2.26 (1.48) | 0–4 |

| Mental Health | ||

| Anxiety | 2.24 (.85) | 1–5 |

| Depressive symptoms | 1.30 (.62) | .10–2.90 |

| Victimization | ||

| Sexual street victimization | .43 (.79) | 0–4 |

| Physical street victimization | .91 (.81) | 0–3 |

Note: M = Mean; SD = standard deviation.

Multivariate Results

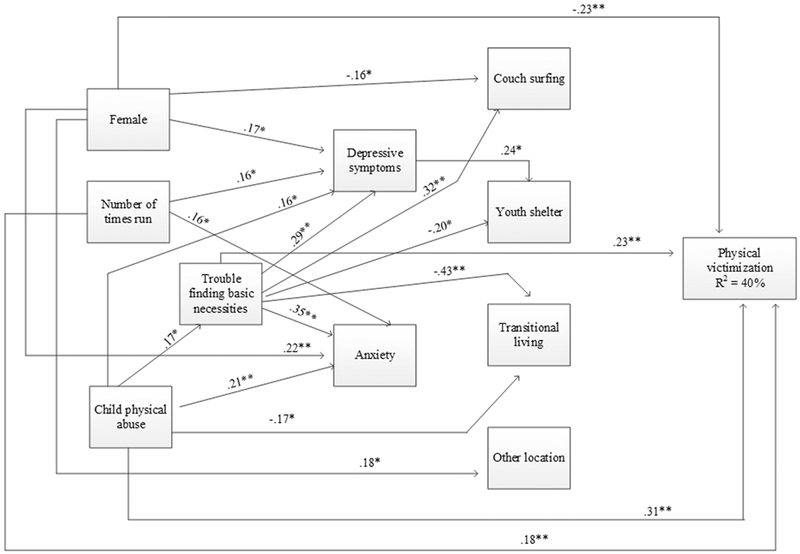

Physical Victimization Model

Path analysis results for physical victimization (only significant paths given) shown in Figure 1 revealed positive associations between both distal and more proximal events. That is, females (β = .17; p ≤ .05), those who ran away from home more often (β = .16; p ≤ .05), those who experienced more child physical abuse (β = .16; p ≤ .05), and those who had more trouble finding basic necessities (β = .29; p ≤ .01) reported more depressive symptoms. Additionally, females (β = .22; p ≤ .01), those who ran away from home more frequently (β = .16; p ≤ .05), those who experienced more child physical abuse (β = .21; p ≤ .01), and those youth who had more trouble finding basic necessities (β = .35; p ≤ .01) reported higher anxiety.1

Fig. 1.

Correlates of physical street victimization (only significant paths shown).

Notes: Temporarily staying with family member is the omitted “sleeping arrangement” category. Because no variables were associated with “adult shelter” we removed variable from figure. **p≤.01; *p≤.05.

Males (β = −.16; p ≤ .05) and those who had more trouble finding basic necessities (β = .32; p ≤ .01) were more likely to report couch surfing (i.e. staying with friends) the previous night. In terms of more proximal experiences, those who reported higher depressive symptoms (β = .24; p ≤ .05) but had less trouble finding basic necessities (β = −.20; p ≤ .05), were more likely to have stayed at a youth shelter the previous night compared to youth staying with a family member (the omitted category). A combination of both distal and proximal life events was also evident in shaping outcomes, as homeless youth who reported lower rates of child physical abuse (β = −.17; p ≤ .05) and less trouble finding basic necessities (β = −.43; p ≤ .01) were more likely to have stayed at a transitional living facility the previous night compared to those staying with a family member. Additionally, females (β = .18; p ≤ .05) were more likely to have stayed at other locations (e.g. in their car) the past night compared to youth staying with a family member. Finally, in considering how both distal and proximal life stressors influence youth, males (β = −.23; p ≤ .01), those who ran away from home more often (β = .18 p ≤ .01), those who experienced more child physical abuse (β = .31; p ≤ .01), and youth who had more trouble finding basic necessities (β = .23; p ≤ .01) reported higher levels of physical street victimization. This model explained 40% of the variance in physical street victimization.

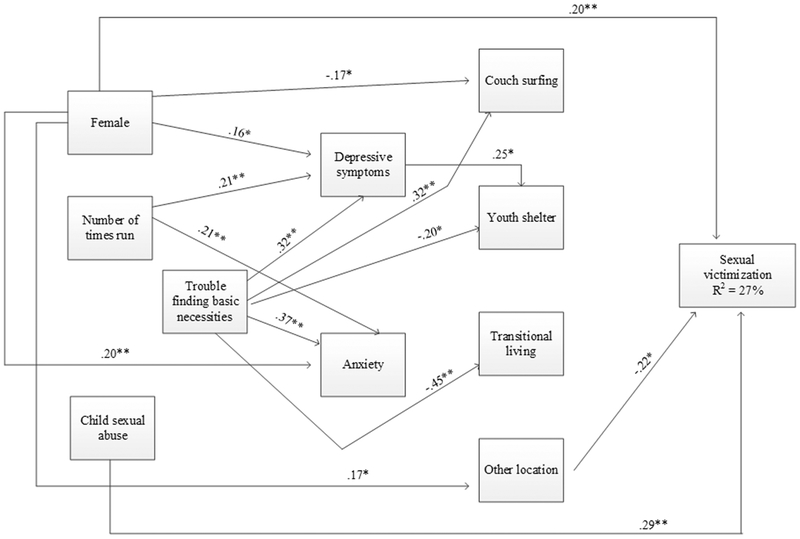

Sexual Victimization Model

Path analysis results for sexual victimization shown in Figure 2 revealed that females (β= .16; p ≤ .05), those who ran away from home more often (β = .21; p ≤ .01), and youth who had more trouble finding basic necessities (β = .32; p ≤ .01) reported more depressive symptoms. Additionally, distal and proximal events impacted youth’s mental health stressors, such that females (β = .20; p ≤ .01), those who ran away from home more frequently (β = .21; p ≤ .01), and those who had more trouble finding basic necessities (β = .37; p ≤ .01) reported higher anxiety.

Fig. 2.

Correlates of sexual street victimization (only significant paths shown).

Notes: Temporarily staying with family member is the omitted “sleeping arrangement” category. Because no variables were associated with “adult shelter” we removed variable from figure. **p≤.01; *p≤.05.

In terms of proximal experiences and outcomes, males (β = −.17; p ≤ .05) and those who had more trouble finding basic necessities (β = .32; p ≤ .01), were more likely to report couch surfing (i.e. staying with friends) the previous night, whereas those who reported higher depressive symptoms (β = .25; p ≤ .05) but had less trouble finding basic necessities (β = −.20; p ≤ .05), were more likely to have stayed at a youth shelter compared to youth staying with a family member. From a proximal life stress perspective, homeless youth who reported less trouble finding basic necessities (β = −.45; p ≤ .01) were more likely to have stayed at a transitional living facility the previous night compared to those staying with a family member. Additionally, females (β = .17; p ≤ .05) were more likely to have stayed at other locations (e.g. in their car) compared to youth staying with a family member.

Finally, when considering both distal experiences and proximal life stressors, females (β = .20; p ≤ .01) and those who experienced more child sexual abuse (β = .29; p ≤ .01), experienced more sexual street victimization compared to males and those with lower rates of sexual abuse. Moreover, the significant impact of the proximal life event of where youth slept the previous night showed that compared to those staying with a family member, youth staying at another location such as a violence shelter (β = −.22; p ≤ .05), experienced lower rates of sexual victimization. It is noteworthy that the path from couch surfing to sexual victimization was marginally significant (β = −.20; p = .06). This model explained 27% of the variance in sexual street victimization.

Though we examined indirect effects for the number of times youth have run away, child sexual and physical abuse, trouble finding basic necessities, depressive symptoms, and anxiety, none of these variables had a significant indirect effect with physical or sexual street victimization.

Discussion

Using a life stress perspective, this study examined the relationships between distal and proximal events including child abuse, finding necessities, mental health, and temporary sleeping arrangements using multiple levels of influence and their association with physical and sexual street victimization among 150 homeless youth. Overall, we find that child sexual and physical abuse are important correlates of sexual and physical street victimization among homeless youth. Those who report a history of child physical abuse also report feeling more anxious, more depressed, and have more trouble locating basic necessities. Moreover, females are at greater risk for sexual victimization, whereas males are more likely to experience physical victimization. Youth who have trouble locating basic necessities report poorer mental health and youths’ ability to locate basic necessities is associated (either positively or negatively) with each type of previous night sleeping arrangement with the exception of other location (e.g. outside or in a car) and adult shelter. Staying at a youth shelter is linked with having more depressive symptoms.

Finally, we find that having trouble locating basic necessities is positively associated with physical street victimization, whereas staying at other locations is negatively associated with sexual street victimization. These multiple linkages at the individual, family, and environmental levels, which include both distal and proximal events have rarely been examined holistically in research on homeless youth, yet they have important implications for policy and prevention.

For our physical victimization model, our findings show that youth who experience more child physical abuse prior to leaving home report higher past week anxiety and more past week depressive symptoms, suggesting that early trauma may continue to impact some youths’ mental health even after they leave home. Additionally, we find that adolescents who suffered more child physical abuse prior to leaving home also experience more physical victimization once on the street, which coincides with prior research (Kort-Butler et al., 2011; Tyler & Melander, 2015). These findings are consistent with a life stress framework (Pearlin, 1989) as both distal and proximal events are associated and the examination of multiple levels of influence (i.e. individual, family, and environment) are needed to fully understand the multifaceted victimization process. Also consistent with a life stress framework, we find that adolescents exposed to early or distal stressors prior to leaving home (i.e. child physical abuse) report poorer past week mental health and more physical victimization since leaving home, indicating that significant relationships exist between these clusters of stressors. More adverse mental health outcomes may be especially detrimental for adolescents who do not receive counseling or for those who lack a strong support network (Brown, Begun, Bender, Ferguson, & Thompson, 2015) and have few people on whom they can rely.

For both models, we find a positive relationship between the stressors of frequency of running away from home and higher anxiety and more depressive symptoms. One possible explanation for this finding is that these adolescents have experienced abuse or family conflict, and running away may be a way to cope with the situation. However, when these youths later return home and abuse or conflict ensues, they may be at greater risk for running away again (Tyler & Schmitz, 2013). Running away numerous times can have the unintended consequence of fracturing social ties, resulting in fewer people that youth can rely on for support (Bao et al., 2000). Moreover, running away multiple times can lead youth to become embedded in residential instability and have greater difficulty exiting street life (Auerswald & Eyre, 2002). Additionally, we find that depressive symptoms are positively correlated with staying at a youth shelter on the previous night. Among homeless youth, there is some evidence that depressive symptoms are linked to youth shelter and drop-in center usage (Hohman et al., 2008), so it may be that mental health concerns drive youth to seek out shelter services. Other research also underscores some homeless youths’ dissatisfaction with youth shelters’ strict enforcement of guidelines and regulations (Karabanow, Hughes, Tichnor, & Kidd, 2010; Thompson, McManus, Lantry, Windsor, & Flynn, 2006), which can also shape mental health challenges.

Youth who report experiencing the stress of more trouble finding basic necessities are more likely to report couch surfing the previous night (in both models). It is possible that some youth who are not able to obtain basic necessities turn to friends for support, such as a place to spend the night. Additionally, it is possible that these young people have a social network of friends who can assist them, albeit temporarily, with a place to sleep. One-quarter of current study youth report couch surfing on the previous night, suggesting that many young people are choosing this option when they have trouble finding shelter. Alternatively, some youth may prefer to stay with friends because they feel safer at these known locations. Homeless youth may view other sleeping arrangements, such as an adult or youth shelter, unsuitable if they are in areas they deem unsafe (Thompson et al., 2006). In fact, we find that youth who have trouble locating necessities are less likely to stay in youth shelter, suggesting that young people are less likely to seek out shelter services if they have alternative sleeping arrangements (i.e. couch surfing) available to them. Also, youth who have more trouble finding basic necessities are less likely to report a transitional living facility as their sleeping arrangement on the previous night. It is possible that youth who have trouble finding basic necessities may not be aware of any services from which they could benefit (Ha et al., 2015) or they may choose not to use any services (Tyler et al., 2012), and thus are less likely to be seeking services through transitional living.

Finally, for the physical victimization model, we find that having more trouble finding necessities is positively associated with the proximal stressor of street physical victimization. It is possible that some youth may resort to stealing or robbing to obtain the items they need, but the situation can quickly change as the perpetrator can become the victim and vice versa (Kennedy & Baron, 1993). Thus, if youth have trouble locating necessities and are trying to access the items they need through criminal means, this likely increases their risk for physical victimization. Alternatively, youth who have been physically victimized may be less trusting of others in general and thus may be reluctant to ask for help or use services even if they are available.

Regarding the sexual victimization model, females and those who experience more child sexual abuse prior to leaving home also endure the heightened stressor of sexual street victimization. These findings are consistent with prior research (Tyler & Melander, 2015) and a life stress framework (Lin & Ensel, 1989; Pearlin, 1989), in that both family (i.e. child abuse) and environmental (street victimization) risk factors are important for explaining the relationship between early and later forms of victimization among homeless youth. Additionally, youth exposed to one serious stressor (i.e. child sexual abuse) are at risk for exposure to additional stressors (i.e. street sexual victimization), which also coincides with our framework in that stressors tend to cluster together (Pearlin, 1989). Thus, homeless youth with early experiences of abuse also report more re-victimization, which is supported by current research (Harris et al., 2017) and helps illuminate the complex nature of the victimization process.

Finally, in the sexual victimization model we find that, compared to youth staying with a family member, staying at other locations is negatively associated with sexual street victimization. One possible explanation for this finding is that two of those “other locations” included a violence shelter and a maternity group home. Thus, young homeless women sleeping in these locations may be ensured a distinctive level of safety not found in other sleeping arrangements, thus, they are at lower risk for repeat victimization. Alternatively, those with prior sexual victimization experiences on the street may be more likely to have been referred to a violence shelter by agency staff, which may also explain the negative relationship between “other location” and sexual victimization on the street.

Limitations

Our study has limitations. First, data are based on self-reports and the retrospective nature of some measures may have resulted in recall bias. Also, we do not have a random sample so our findings cannot be generalized to all homeless youth. However, given that much of the research on homeless youth has been conducted in coastal areas and other major metropolitan cities, a sample from the Midwest is a study strength. Another limitation is that youth were only asked about their sleeping arrangements for the prior night. Because it is possible that youth change sleeping arrangements frequently, this might explain why many of the sleeping arrangement variables were not associated with victimization. Finally, though our path models imply a causal order, our study is cross-sectional; thus, we are only examining associations among study variables.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, this paper further contributes to our understanding of various life stress factors that threaten the safety and well-being of adolescents and youth throughout their life experiences. Future studies may wish to replicate our findings to see whether these same sleeping arrangements are associated with street victimization among other samples of homeless youth. Relatedly, homeless young people might be vulnerable to sex trafficking (Varma, Gillespie, McCracken, & Greenbaum, 2015), but may not answer affirmatively to the sexual victimization items because of discordant definitions of sexual assault or out of fear of retribution. Future studies might consider screening for this additional type of victimization to more fully capture the diversity of adverse experiences of homeless youth and more adequately improve services and interventions aimed at their well-being, particularly in ensuring youths’ safe sleeping arrangements to minimize their vulnerability. Additionally, research documenting youths’ sleeping arrangements for an extended period of time (e.g. two to four weeks) is needed so that it can be determined how frequently youth change sleeping locations and if stability at one location (e.g. couch surfing) is a protective factor or risk factor for victimization. Our findings show that couch surfing (marginally significant) may be a protective factor against sexual victimization, but this may depend on the number of days youth spend at that particular sleeping location as well as whose house they are couch surfing at (e.g. trusted friend or an acquaintance). Knowing more about the consistency of youths’ sleeping patterns would allow researchers to examine this association with physical and sexual victimization in greater depth.

Also, there is a paucity of research on youths’ ability to locate services, so additional exploration into this topic and knowing more about how youth learn about services and their likelihood of using them would assist agencies serving this population. This is especially important given that research finds that some homeless youth who lack food, money, or a place to stay resort to trading sex to obtain such necessities, and trading sex has been found to be associated with experiencing sexual victimization among both male and female homeless adolescents (Tyler et al., 2004). As such, knowing more about why youth are not using certain services, such as youth shelter (Carlson et al., 2006), and youths’ prior experience with accessing services (Solorio et al., 2006), may be beneficial to service agencies as some of these issues, particularly awareness of services, may be easily overcome using billboards and other advertisements featuring available services for adolescents and youth in need.

Highlights.

We examine risk factors for homeless youths’ sexual and physical victimization.

Child physical abuse is associated with mental health and street physical victimization.

Youths’ ability to locate basic necessities is linked to their sleeping arrangements.

Having trouble finding necessities is associated with physical victimization.

Certain sleeping arrangements (e.g., violence shelter, in a car) lower risk for sexual victimization.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This article is based on research funded by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA036806). Dr. Kimberly A. Tyler, PI.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

In both path models (Figures 1 and 2), the variable “adult shelter” was not associated with any of the variables; therefore, this variable was removed from both figures.

Sources of Conflict

There are no sources of conflict for either author.

Contributor Information

Kimberly A. Tyler, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Department of Sociology Lincoln, NE 68588-0324.

Rachel M. Schmitz, Oklahoma State University, Department of Sociology, Stillwater, OK

References

- Afifi TO, MacMillan H, Cox BJ, Asmundson GJ, Stein MB, & Sareen J (2008). Mental health correlates of intimate partner violence in marital relationships in a nationally representative sample of males and females. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 8, 1398–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerswald CL, & Eyre SL (2002). Youth homelessness in San Francisco: A life cycle approach. Social Science & Medicine, 54, 1497–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao WN, Whitbeck LB, & Hoyt DR (2000). Abuse, support, and depression among homeless and runaway adolescents. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41, 408–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender K, Brown SM, Thompson SJ, Ferguson KM, & Langenderfer L (2015). Multiple victimizations before and after leaving home associated with PTSD, depression, and substance use disorder among homeless youth. Child Maltreatment, 20, 115–124. doi: 10.1177/1077559514562859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender K, Ferguson KM, Thompson SJ, & Langenderfer L (2014). Mental health correlates of victimization classes among homeless youth. Child Abuse and Neglect, 38, 1628–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SM, Begun S, Bender K, Ferguson KM, & Thompson SJ (2015). An exploratory factor analysis of coping styles and relationship to depression among a sample of homeless youth. Community Mental Health Journal, 51, 818–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson J, Sugano E, Millstein S, & Auerswald C (2006). Service utilization and the life cycle of youth homelessness. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38, 624–627. DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endler NS, Parker JDA, Bagby RM, & Cox BJ (1991). Multi-dimensionality of state and trait anxiety: Factor structure of the Endler multidimensional anxiety scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 919–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Bailey SL, & Federman EB (1999). Social network characteristics associated with risky behaviors among runaway and homeless youth. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 40, 63–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha Y, Narendorf SC, Santa Maria D, & Bezette-Flores N (2015). Barriers and facilitators to shelter utilization among homeless young adults. Evaluation Program Planning, 53, 25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris T, Rice E, Rhoades H, Winetrobe H, & Wenzel S (2017). Gender differences in the path from sexual victimization to HIV risk behavior among homeless youth. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 26, 334–351. DOI: 10.1080/10538712.2017.1287146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohman M, Shillington AM, Min JW, Clapp JD, Mueller K, & Hovell M (2008). Adolescent use of two types of HIV prevention agencies. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention in Children & Youth, 9, 175–191. [Google Scholar]

- Karabanow J, Hughes J, Ticknor J, & Kidd S (2010). The economics of being young and poor: How homeless youth survive in neo-liberal times. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 37, 39–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy LW, & Baron WW (1993). Routine activities and a subculture of violence: A study of violence on the street. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 30, 88–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kort-Butler LA, & Tyler KA (2012). A cluster analysis of service utilization and incarceration among homeless youth. Social Science Research, 41, 612–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kort-Butler LA, Tyler KA, & Melander LA (2011). Childhood maltreatment, parental monitoring, and self-control among homeless young adults. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 38, 1244–1264. [Google Scholar]

- Lee BA, Tyler KA, & Wright JD (2010). The new homeless revisited. Annual Review of Sociology, 36, 501–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin N, & Ensel WM (1989). Life stress and health: Stressors and resources. American Sociological Review, 54, 382–399. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998-2015). Mplus User’s Guide. (7th ed.). Los Angeles,CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- National Center on Family Homelessness at AIR. (2014). America’s youngest outcasts: A report card on child homelessness. Waltham, MA: The National Center on Family Homelessness at American Institutes for Research; Retrieved January 4, 2016. (http://www.air.org/sites/default/files/downloads/report/Americas-Youngest-Outcasts-Child-Homelessness-Nov2014.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Homeless Education (NCHE) and the National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and Youth (NAEHCY). (updated 2017). “Definitions of Homelessness for Federal Programs Serving Children, Youth, and Families.” Retrieved February 24, 2018. (https://nche.ed.gov/downloads/briefs/introduction.pdf)

- Pearlin LI (1989). The sociological study of stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 30, 241–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rattelade S, Farrell S, Aubry T, & Klodawsky F (2013). The relationship between victimization and mental health functioning in homeless youth and adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29, 1606–1622. DOI: 10.1177/0886260513511529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solorio MR, Milburn NG, Andersen RM, Trifskin S, & Rodrigues MA (2006). Emotional distress and mental health service use among urban homeless adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 33, 381–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, & Runyan D (1998). Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22, 249–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SJ, McManus H, Lantry J, Windsor L, & Flynn P (2006). Insights from the street: Perceptions of services and providers by homeless young adults. Evaluation and Program Planning, 29, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA, Akinyemi SL, & Kort-Butler LA (2012). Correlates of service utilization among homeless youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 34, 1344–1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA, & Beal MR (2010). The high-risk environment of homeless young adults: Consequences for physical and sexual victimization. Violence & Victims, 25, 101–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA, Hoyt DR, Whitbeck LB, & Cauce AM (2001). The effects of a high-risk environment on the sexual victimization of homeless and runaway youth. Violence & Victims, 16, 441–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA, & Melander LA (2015). Child abuse, street victimization, and substance use among homeless young adults. Youth & Society, 47, 502–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA, & Olson K (2018). Examining the feasibility of ecological momentary assessment using short message service surveying with homeless youth: Lessons learned. Field Methods, 30, 91–104. 10.1177/1525822X18762111 (Published Online First April 16, 2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA, & Schmitz RM (2013). Family histories and multiple transitions among homeless young adults: Pathways to homelessness. Children and Youth Services Review, 35, 1719–1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA, Schmitz RM, & Ray CM (2017). Role of social environmental factors on anxiety and depressive symptoms among midwestern homeless youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence. Published online May 31, 2017 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jora.12326/full [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, & Cauce AM (2004). Risk factors for sexual victimization among male and female homeless and runaway youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19, 503–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma S, Gillespie S, McCracken C, & Greenbaum VJ (2015). Characteristics of child commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking victims presenting for medical care in the United States. Child Abuse & Neglect, 44, 98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, & Simons RL (1990). Life on the streets: The victimization of runaway and homeless adolescents. Youth & Society, 22, 108–125. [Google Scholar]