Abstract

Depth filtration is a commonly-used bioprocessing unit operation for harvest clarification that reduces the levels of process- and product-related impurities such as cell debris, host-cell proteins, nucleic acids and protein aggregates. Since depth filters comprise multiple components, different functionalities may contribute to such retention, making the mechanisms by which different impurities are removed difficult to decouple. Here we probe the mechanisms by which double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) is retained on depth filter media by visualizing the distribution of fluorescently-labeled retained DNA on spent depth filter discs using confocal fluorescence microscopy. The extent of DNA displacement into the depth filter was found to increase with decreasing DNA length with increasing operational parameters such as wash volume and buffer ionic strength. Finally, using 5ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) to label DNA in dividing CHO cells, we showed that Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cellular DNA in the lysate supernatant migrates deeper into the depth filter than the lysate re-suspended pellet, elucidating the role of the size of the DNA in its form as an impurity. Apart from aiding DNA purification and removal, our experimental approaches and findings can be leveraged in studying the transport and retention of nucleic acids and other impurities on depth filters at a small scale.

Keywords: depth filtration, genomic DNA, DNA oligos, retention, adsorption

1. Introduction

Animal cell culture has been used to produce recombinant proteins for human application since 1985 [1]. Over the subsequent decades the understanding of the risks associated with the cellular components, which are process-related impurities, has evolved. DNA, which is excreted from the cells due to either apoptosis or necrosis, was originally considered a risk factor because the continuous cell lines in question were immortalized, leading to a requirement that DNA be reduced to exceptionally low levels [2,3]. However, after additional findings showing lack of tumor development in primates injected with tumor chromatin [4] and thorough evaluation of the contextual risks [3], the World Health Organization recommended that residual DNA be considered a general cellular contaminant, and up to 10 ng of DNA may be present per dose [5].

Since the perspective on residual DNA has changed to that of a simple impurity, the removal of DNA in downstream operations is tracked primarily in terms of its total mass. DNA is usually quantified based on UV absorbance at 260 nm by the heterocyclic rings in the DNA bases and fluorescence emission upon the intercalation of dye into DNA. Tracking the mass balance of DNA by utilizing these approaches has shown that a range of separations media, including immuno-affinity [6], anion-exchange [7], and size-exclusion [8] resins, as well as filter aids and depth filters [9], can reduce the total amount of DNA by two logs or more. In addition to adsorbent-based purification approaches, DNA removal of three logs has been obtained by precipitation using cationic detergents [10]. Among these methods, determining the mechanisms by which depth filters remove DNA is less straightforward.

Depth filters generally comprise a minimum of three components, each of which can contribute to impurity removal. Cellulose or polypropylene fibers often function as the base material and provide a fibrous network with a nominal retention rating that allows filtration of particulates based on their size as fluid flows along the filter’s tortuous path. Added to the fibers is the second and the most abundant component by mass, the filter aid, typically siliceous materials such as diatomaceous earth (DE), fossilized diatoms that have naturally occurring pore structures, and/or perlite, a glassy volcanic rock [11]. The filter aid provides additional surface area to the depth filter and thereby increases the throughput of the depth filter and contributes to impurity capture. The last component of the depth filter is the polymeric binder, which has varying levels of cationic charge, often resulting from primary to quaternary amine functional groups [12]. The binder chemistries for commercial depth filters are not fully disclosed and may comprise additional components or functionalities to improve the retention of charged impurities [13].

Since depth filters are an amalgamation of disparate components, impurities can be retained on them via various functionalities, as a result of which the mechanisms by which various impurities such as nucleic acids, proteins and cellular debris are removed can be difficult to decouple. Charlton et al. found that buffers that neutralize the charge on the depth filter and impede possible hydrophobic interactions reduced the operational capacity of the depth filter [14], while Singh et al. suggested that while electrostatic interactions are primary in the removal of DNA, other interactions such as hydrogen bonding also play an essential role [15].

The lack of information other than the total mass of the DNA, determined using absorbance or fluorescence methods, can be limiting in inferring the various mechanisms that may be involved. In particular, these measurements cannot shed light on the DNA length and size distribution and their effect on the retention and escape of DNA. DNA secreted from NS0 myeloma cells in the later stages of batch cell culture has been found to comprise both high molecular weight and short oligo-like fragments [16]. The presence of relatively low molecular weight DNA fragments could be linked to the fragmentation of nucleosomes from nuclear chromatin by an intracellular endonuclease during programmed cell death [17]. Charlton et al. investigated the molecular weight of DNA from clarified, large-scale, fed-batch, mammalian cell culture and reported that it is predominantly of less than 1 kDa. However, since both apoptosis and necrosis can be present in cell culture conditions, they could not further determine the source of these smaller DNA fragments with certainty [18].

Keeping in mind the uncertainty of the distribution of length and hence effective size in a DNA impurity, we have investigated the mechanisms involved in the retention of DNA on depth filters by directly visualizing retained DNA on spent depth filters. The distribution of the retained DNA on a spent depth filter need not be the same for two disparate DNA samples of equal total DNA mass, and the differences show the importance of the effect of DNA length and effective size on retention profiles. This is the first instance of which we are aware where the distribution of retained DNA on spent depth filters has been visualized directly to substantiate the importance of DNA size and length distributions on the retention profile.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Monobasic sodium phosphate (NaH2PO4), sodium phosphate dibasic (Na2HPO4), sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), tris base (C4H11NO3), hydrochloric acid (HCl), sodium chloride (NaCl), anhydrous DMSO, NHS-rhodamine, copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate (CuSO4.5H2O), l-ascorbic acid sodium salt (C6H7NaO6), peptone and yeast extract were all purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ). 3M provided samples (discs) of diameter 10 mm of the 90ZB grade commercial depth filter media.

β-lactoglobulin from bovine milk was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). NoLimits™ individual dsDNA fragments of 500 and 5000 base pairs (bp) were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA), while custom-designed dsDNA fragments of 50 bp and 90 bp were ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, Coralville, IA). Bristol-Myers Squibb (Devens, MA) provided CHO genomic DNA of 1.29 mg/mL in 10 mM tris, 1 mM EDTA at pH 8.

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-K1 cell line was provided by the Millicent O. Sullivan research group, University of Delaware. Gibco™ Dulbecco’s modification of Eagle’s medium (DMEM), Gibco™ phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.2, Gibco™ fetal bovine serum (FBS), Gibco™ trypsin-EDTA (0.25%) and Gibco™ penicillin-streptomycin (10,000 U/mL) were purchased from Fisher Scientific. 5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) and 5-TAMRA azide were purchased from Click Chemistry Tools (Scottsdale, AZ).

A cloning vector of 6136 base pairs, pET28a mCherry, was provided by the Joseph M. Fox research group, University of Delaware. Restriction enzymes EcoRI-HF and XbaI were purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA) and HiSpeed plasmid mega extraction kits and QIAquick gel extraction kits were purchased from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany).

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Generating dsDNA fragments of 5226 bp

The plasmid was provided in bacteria streaked on an agar plate. Two to three colonies were inoculated into each of three vials containing 3 mL of lysogeny broth (LB) with 100 μg/mL ampicillin and placed in an incubator at 37 °C for 8 hours. Approximately 4.5 mL of the starter culture was then inoculated into each of two baffled flasks containing 500 mL of LB containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin, which were shaken at 180 rpm for 13 hours at 37 °C. Plasmid DNA was extracted from the resulting culture using a HiSpeed plasmid mega kit from Qiagen (Mansfield, MA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The purified plasmids were digested with EcoRI and XbaI restriction endonucleases at 0.5 unit of each enzyme per μg of dsDNA for 11 hours following the manufacturer’s protocol. Two separate bands at ~ 900 bp and ~ 5000 bp were seen on 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, confirming that the digest was complete. Following digestion, the sample was concentrated by isopropanol precipitation in which isopropanol equivalent to 70% of the sample volume was added to the DNA sample and centrifuged at 161,000 g for 10 minutes. The pellet containing the DNA was dissolved in 50 μL of 10 mM tris, 1 mM EDTA at pH 8.0 prior to extraction via electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel. The two dsDNA fragments were separated using a QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit from Qiagen following the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.2.2. Generating dsDNA fragments of 50 and 90 bps

Randomly generated DNA sequences of 50 bp and 90 bp, with GC content of 40–42 % and Tm of 64–70 ˚C, and their respective reverse complementary strands were purchased from IDT and were annealed following IDT’s protocol. The annealed products were suspended in 10 mM tris with 100 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA at pH 7.5.

2.2.3. dsDNA characterization

The 5226 bp DNA fragment was analyzed using a multi-angle light scattering detector, Dawn Heleos II, from Wyatt, over a collection period of 5 minutes. Scattering intensities for sample concentrations of 0.045, 0.091, 0.136 and 0.181 mg/mL were measured across the detectors at 64, 72, 81, 90 and 108 degrees from the sample cell to construct a Zimm plot, consistent with the relation for the Rayleigh ratio Rθ in terms of the form factor for small submicron particles that scatter light [19]:

| (1) |

In the equations below, n, λ, and c denote the refractive index, laser wavelength, and sample concentration, respectively, while

| (2) |

where NAV is Avogadro’s number. The Zimm plot allows simultaneous extrapolation of the experimental static light scattering intensity to both the zero angle and zero concentration limits to allow the molecular weight Mw, second virial coefficient A2, and radius of gyration Rg to be estimated. As shown in Equation 1, in the limit of zero concentration, Rg can be estimated from the slope of the plot of Kc/Rθ as a function of sin2(θ/2) + B c, where B is an arbitrary constant that is selected to ensure that the concentration term is of a comparable magnitude to sin2(θ/2), which varies from 0 to 1 [20]. The radius of gyration was inferred in the limit of sample concentrations approaching zero. An isotropic scatterer, bovine serum albumin (0.75 mg/mL), was used to normalize the light scattering detectors in each buffer under consideration, which relates the measured voltage at each detector to that of the 90˚ detector and offset the differences in the gain between the detectors. Toluene was used as a standard for instrument calibration and the scattering from the respective buffers was subtracted from that of the sample of interest.

2.2.4. β-lactoglobulin and DNA labeling

β-lactoglobulin was fluorescently labeled via its primary amine groups using NHS-Rhodamine (ThermoFisher Scientific), following the manufacturer’s protocol with some modifications. NHS-Rhodamine was dissolved in DMSO at 10 mg/mL and was added to 1 mL of a 10 mg/mL β-lactoglobulin solution in 100 mM sodium phosphate, 150 mM sodium chloride, pH 7.4, at a molar dye-to-protein ratio of 0.5:1. Label IT® nucleic acid labeling kit Cy®5 from Mirus Bio (Madison, WI) was used to covalently tag the cyanine dye along with a linker onto the 7th nitrogen of the guanine base. The manufacturer’s protocol was followed with the exception of a reduction in the ratio of μg of nucleic acid to μL of Label IT® reagent to 1: 0.025 – 0.05.

2.2.5. Chromosomal DNA labeling and lysate preparation

Adherent CHO-K1 cells were labeled using EdU following the protocol described by Salic et al. [21], with modifications. Adherent CHO-K1 cells were grown in DMEM with 10% FBS, penicillin and streptomycin. After the fifth passage at ~40% confluency, EdU was added to the dividing cells at 0, 4, 8 and 12 hours to obtain concentrations of 100, 400, 2500 and 10000 nM, respectively. After an additional 12 hours, the cells were washed with PBS and 10 mL of the staining solution, comprising PBS supplemented with 0.5 mM copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate, 1 μM 5-TAMRA-azide and 50 mM l-ascorbic acid sodium salt, was added to the T-75 flask with adherent cells. The cells were placed in a 37 °C incubator for 30 minutes, after which the staining solution was replaced with PBS and 1 mL trypsin was used to detach the cells and the cells were collected using the previously-described growth media. A 15 mL cellular suspension of ~ 90,000 cells/mL in the growth media was vortexed for 3 minutes and then lysed by passing it 10 times between two syringes connected by a union with a negligible orifice and a low dead volume. The overall time elapsed was approximately 1 minute. One third of the lysate was kept for analysis of its retention on the depth filter while the rest was centrifuged at 4500 rpm for 1 hour. After centrifugation, the supernatant was collected while the pellet was resuspended in 4 mL of the growth media.

2.2.6. Sample loading onto the depth filter

Depth filter (90ZB) discs 10 mm in diameter were punched out using a custom-made punching set comprising a male and a female part. The disc was then inserted into the online filter holder of an Äkta Explorer in place of the standard 10 mm diameter polypropylene filter and placed on a column position. The standard operating procedure comprised washing of the filter using 13 mL (165.6 L/m2) of the buffer under consideration at a flow rate of 1.5 mL/min (1146.5 LMH), followed by loading of a 2 mL (25.5 L/m2) sample at 1 mL/min (764.3 LMH) and washing with 5 mL (63.7 L/m2) of the same buffer at 1 mL/min (764.3 LMH). The pressure drops during the experiments with the 90ZB depth filter were approximately 0.35 – 0.4 MPa. The only significant increase in pressure seen during sample loading was by about 10%, during loading of the resuspended lysate pellet. The depth filter pieces were subsequently stored at –20 °C for 3–48 hours in an opaque container until they were visualized by confocal microscopy.

2.2.7. Depth filter visualization and image analysis

After sample loading, the 10 mm 90ZB depth filter discs were sliced along the center using a MITER CUT precision cutting tool (Lexington, KY) to give two approximately equal three-dimensional arcs. The wet sliced faces of the half discs were placed on a glass slide, making sure there was a minimal gap between them, and visualized on a Zeiss 710 inverted confocal microscope (Oberkochen, Germany) using a Zeiss 10× EC Plan-Neofluar (0.3 NA) objective. The laser intensity, gain and pinhole were kept constant in visualizing the comparative sample sets to allow for direct and qualitative comparison. The depth probed along the z-axis (depth into the samples) was also kept similar (± 2 μm) to ensure that the densities of collapsed visualizations were comparable. Fixed-area thresholding was performed in Image J between a set of images, where direct comparisons of the extent of DNA penetration were made.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. DNA vs. protein retention

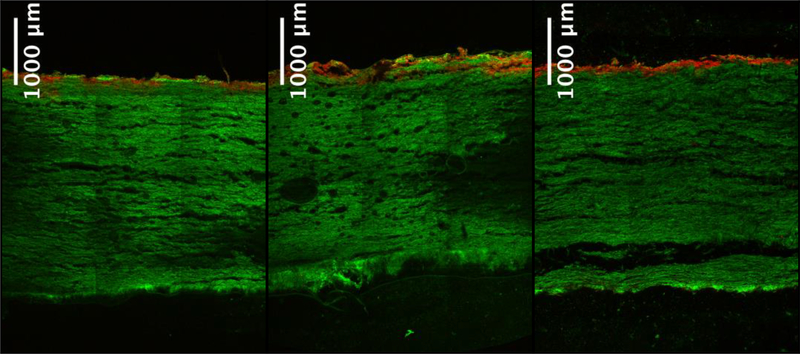

The retention of CHO genomic DNA (red) and β-lactoglobulin (green) on the 90ZB depth filter is shown in Figure 1. Fifteen μg DNA and 2 mg β-lactoglobulin were loaded in all three cases using 2 mL of 10 mM sodium phosphate at pH 8, but three modes of loading were used in order to probe the mechanisms driving DNA retention. In Figure 1a, β-lactoglobulin was loaded first, followed by DNA, while in Figure 1b, DNA was loaded first, then β-lactoglobulin was loaded after the depth filter was flipped over to reverse the flow direction. These modes were used to determine whether the presence of one species would affect the subsequent retention of the other, specifically whether DNA would compete with β-lactoglobulin in adsorbing onto the depth filter or would co-exist via means other than adsorption. The filter was flipped after the loading of DNA in Figure 1b to determine, in addition, whether the retained DNA would break through, remain stationary or rearrange in position with flow in the opposing direction. For the results in Figure 1c, DNA and β-lactoglobulin were mixed just prior to loading.

Figure 1.

Retained CHO genomic DNA (red) and β-lactoglobulin (green) on the 90ZB depth filter; overlapping regions appear orange. (a) β-lactoglobulin was loaded first followed by DNA; (b) DNA was loaded first, then the depth filter was flipped over to load β-lactoglobulin with the flow reversed; (c) DNA and β-lactoglobulin were premixed and loaded simultaneously. Fifteen μg DNA and 2 mg β-lactoglobulin were loaded in all three cases using 2 mL of 10 mM sodium phosphate at pH 8.

β-lactoglobulin saturates the depth filter while DNA is retained near the top face of the filter in all cases. Figures 1a and 1c are similar in that the DNA appears to be retained primarily on the surface. Whether DNA is loaded prior to protein or along with protein does not appear to impact the extent to which DNA is able to migrate into the filter. It is also worth noting that although the 90ZB depth filter has a nominal retention rating of 0.2 μm [12], it has a pore size gradient along the depth of the filter, so the pores become narrower with depth into the filter.

Our previous work [22] showed that the 90ZB depth filter’s adsorption capacity for β-lactoglobulin is ~ 1.7 mg/m2 using 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 8 and that the 90ZB depth filter has a specific surface area of 4.86 m2/mg. Given that a 90ZB depth filter disc of 10 mm in diameter weighs 90–120 mg, we can deduce that our filter is able to retain only ~ 0.75–1 mg of β-lactoglobulin. Hence, it is saturated with protein and DNA resides along with the protein at the upper surface. The distribution of DNA in the case where the filter is flipped after loading DNA, prior to loading protein, is less dense and the DNA is present to a greater depth (Figure 1b). This and the filter’s saturation by protein suggest that the DNA is not strongly adsorbed and is able to redistribute with flow. Furthermore, it is possible that some DNA was lost in the scenario shown in Figure 1b. The flow in this case during protein loading is in the direction of increasing pore size, whereas in the case of Figure 1a, the flow is in the direction of decreasing pore size.

3.2. Effect of sample and process parameters

In order to determine whether the retention of CHO genomic DNA on the filter surface was due primarily to the large size of CHO genomic DNA or to a limited injected sample mass (15 μg), the retention profiles of a larger quantity of genomic DNA as well as of a DNA oligo were explored. Figures 2a, 2b and 2c show the retention of 15 μg of CHO genomic DNA, 500 μg of CHO genomic DNA and 300 μg of a 90 bp DNA oligo, respectively, loaded using 2 mL of 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 8 on the 90ZB depth filter. Although further displacement into the filter is seen in Figure 2b compared to that in Figure 2a, the difference in the extent to which DNA penetrates into the depth filter is not significant given the 33-fold increase in the mass of CHO genomic DNA loaded. This finding indicates that while the retention of proteins like β-lactoglobulin is driven primarily by electrostatic interactions between the protein and the resin binder of the depth filter [22], the retention of DNA, which can be present in a wide range of sizes, is dictated largely by size-based retention effects.

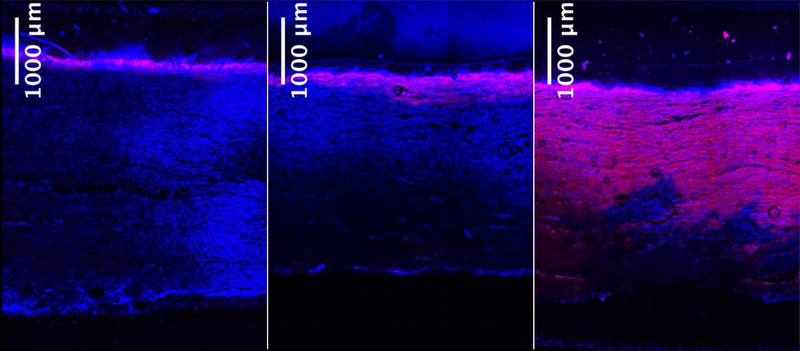

Figure 2.

Retained DNA on the 90ZB depth filter. DNA is shown in red while the depth filter’s autofluorescence in the blue region is shown in blue and the overlapping regions appear pink. (a, b) 15 μg and 500 μg CHO genomic DNA, respectively, were loaded following the standard procedure. (c) 300 μg of 90 bp DNA oligo was loaded. All three samples were loaded using 2 mL of 10 mM sodium phosphate at pH 8.

Compared to the limited permeability of CHO genomic DNA, the DNA oligo of 90 bp was able to penetrate the depth filter significantly further and was retained in a manner similar to that of β-lactoglobulin (Figure 2c). The 90 bp oligo molecular weight of 55.5 kDa is of the same order of magnitude as β-lactoglobulin (18.4 kDa), and although the size of the DNA may be significantly greater than that of protein (see below), electrostatic interactions and short-range interactions are likely play a greater role in its retention if it remains much smaller than the depth filter pores.

3.3. Correlations among DNA length, effective size and penetration

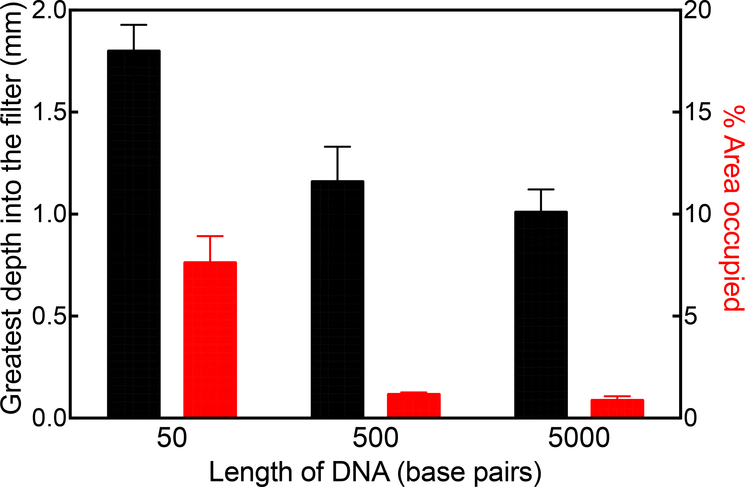

Figure 3 shows the retention of 10 μg each of three DNA fragments of different length, loaded in 2 mL of 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 8. The qualitative reduction in the extent of DNA penetration with increasing DNA length is apparent, but a more quantitative interpretation of the confocal images was obtained by fixed area thresholding of the three images under comparison. Figure 4 shows a quantitative decrease in the extent of DNA penetration as a function of DNA length as expressed through the greatest depth into the filter, which is defined as the distance from the surface of the filter to the furthest distance the DNA has reached, and the % area of the depth filter where the DNA is seen. The data suggest that size-based retention of DNA is a combined effect of DNA length and the pore size gradient along the depth of the filter.

Figure 3.

Retained DNA of (a) 50, (b) 500 and (c) 5000 bp on the 90ZB depth filter. DNA is shown in red while depth filter autofluorescence in the blue region is shown in blue and the overlapping regions appear pink. DNA sample masses of 10 μg were loaded in all three samples using 2 mL of 10 mM sodium phosphate at pH 8.

Figure 4.

Retention of DNA fragments of 50, 500 and 5000 bp on the 90ZB depth filter represented as the greatest depth into the filter (black) and the % area occupied (red).

In order to interpret the extent of penetration into the depth filter (Figure 4) in terms of the effective size of DNA as a function of the contour length, efforts were made to estimate the effective size. For the 5226 bp DNA sample, the radius of gyration was estimated from static light scattering (SLS) using a Zimm plot as 124 ± 6 nm (95% confidence interval). This value is slightly smaller than for comparable studies in the literature, although fairly consistent given differences in the sample environment [23–25]. The geometric diameter, relevant to the study of retention and penetration through the filter, would then be of order 300 nm. Since the nominal retention rating of the 90ZB filter is 200 nm, it is reasonable that DNA fragments of ~5000 bp would not penetrate a depth filter, as shown in Figure 3c.

The SLS interpretation is less clear for the 500 bp sample and SLS data were unobtainable for the 50 bp sample. However, alternative insights emerge from an analysis using a contour length of 0.33 nm/bp [26,27], which gives contour lengths of 165 nm and 16.5 nm for the respective samples. Since the persistence length of DNA is approx. 50 nm [28,29], these two samples may be better represented as a bent fiber (500 bp) or a rigid rod (50 bp) than as globular coils. The resulting lack of a well-defined characteristic dimension and the possibility of alignment of the DNA with the flow field make clear conclusions regarding effective size problematic. However, for these two samples, retention by a nominal 200 nm filter appears likely to be either only partial or negligible, generally consistent with the results for these two samples in Figure 4.

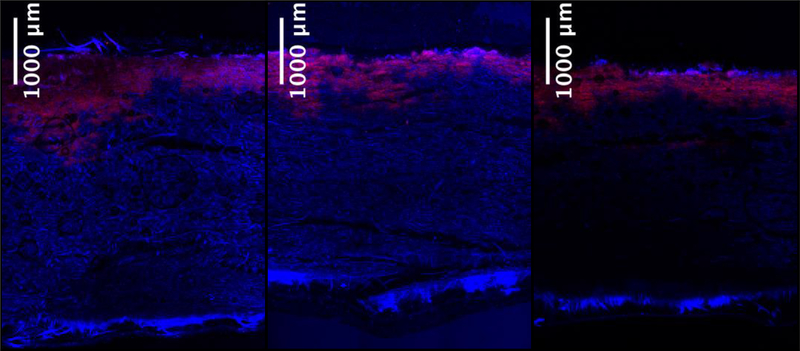

3.4. Effect of wash volume and buffer ionic strength

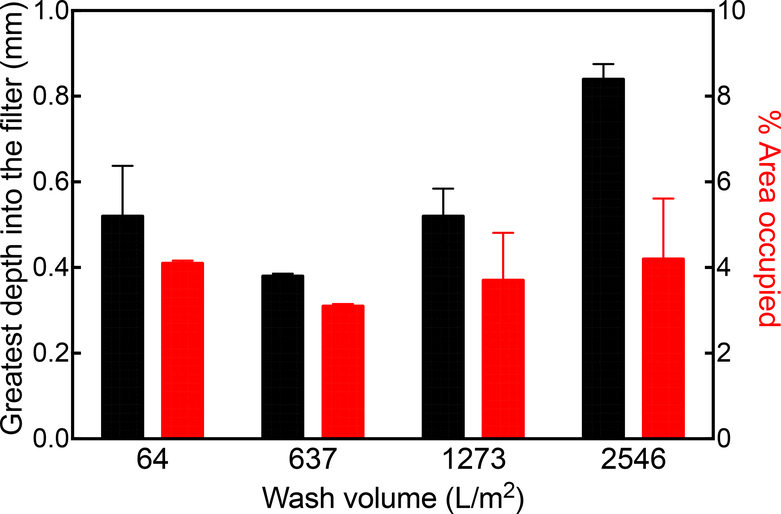

Apart from the effect of the size of the DNA, the effect of operational parameters such as wash volume and buffer ionic strength on the extent of DNA penetration into the depth filter were also explored. Figure 5 shows that when the loading of 15 μg of CHO genomic DNA in 2 mL of buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 8) was followed by 5, 50, 100 and 200 mL (64–2546 L/m2) of the same buffer at 1528 LMH, the small amount of DNA was displaced further into the depth filter. Figure 6 shows that both the greatest depth into the filter and the % area occupied by each sample increase with increasing wash volume, with the exception of the lowest wash volume. This indicates that large DNA, such as CHO genomic DNA, is not strongly bound or adsorbed onto the filter and is retained primarily through size-based retention effects. Figures 1b and 1c also indicate that DNA, unlike acidic proteins, is not sufficiently strongly bound or adsorbed on the surface to prevent its travel through the filter with flow.

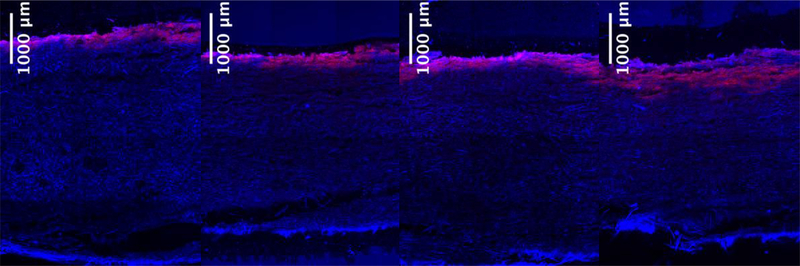

Figure 5.

Effect of wash volume on distribution of retained DNA on the 90ZB depth filter. DNA is shown in red while the depth filter’s autofluorescence in the blue region is shown in blue and the overlapping regions appear pink. 15 μg CHO genomic DNA was loaded, followed by a wash volume of 64, 637, 1273 or 2546 L/m2 at 1528 LMH.

Figure 6.

Retention of CHO genomic DNA on 90ZB depth filter as a function of buffer wash volume. Results are represented as the greatest depth into the filter (black) and the % area occupied (red).

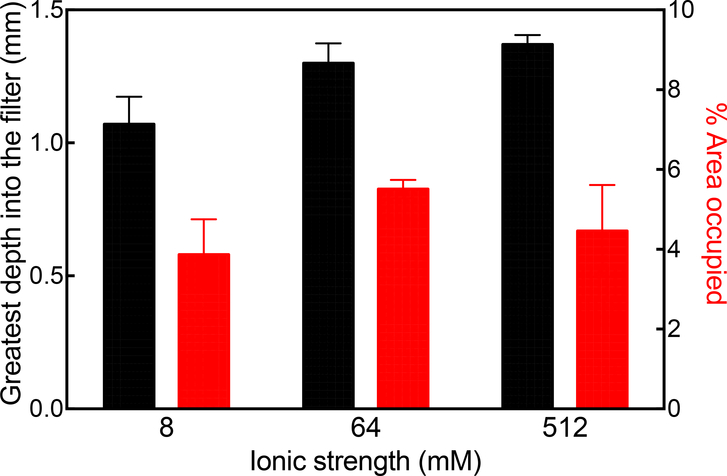

The strength of adsorption can be directly affected by another operational parameter, buffer ionic strength, which was also systematically varied by loading 10 μg of 50 bp DNA oligo using 10 mM tris buffer, pH 7.5, also containing 0, 56 or 504 mM NaCl to give 8, 64 and 512 mM total ionic strengths, respectively. In this experiment, tris buffer was chosen to remove the effect of binding of buffer anions to the depth filter, as is possible with phosphate. Figure 7 shows that the greatest depth into the filter increases with increasing buffer ionic strength, although the difference appears to be more pronounced at lower ionic strengths. This may be due in part to screening of electrostatically-driven adsorption but also screening of intramolecular electrostatic repulsion, which reduces the stiffness of the DNA and allows it to become more compact [27] and hence to penetrate further into the depth filter. Therefore the buffer ionic strength can impact the extent to which DNA, as a process impurity, is retained on the depth filter or escapes into the filtrate.

Figure 7.

Retention of 50 bp DNA fragment on 90ZB depth filter as a function of buffer ionic strength. Results are represented as the greatest depth into the filter (black) and the % area occupied (red).

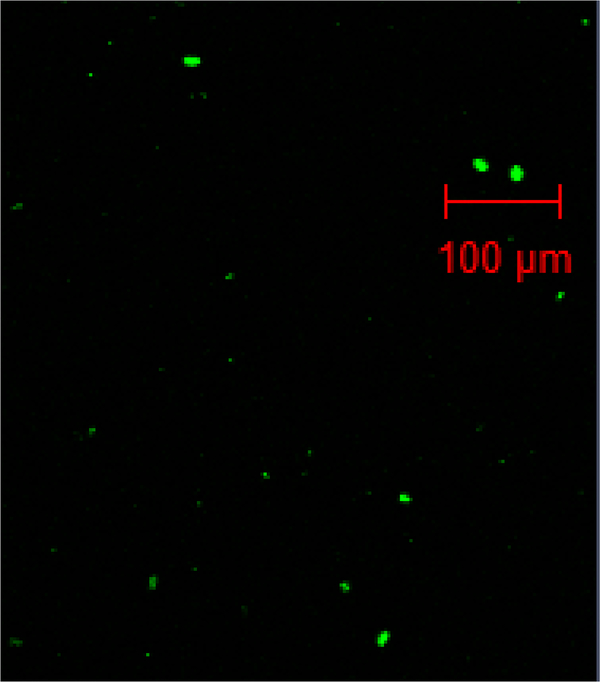

3.5. Retention of chromosomal DNA

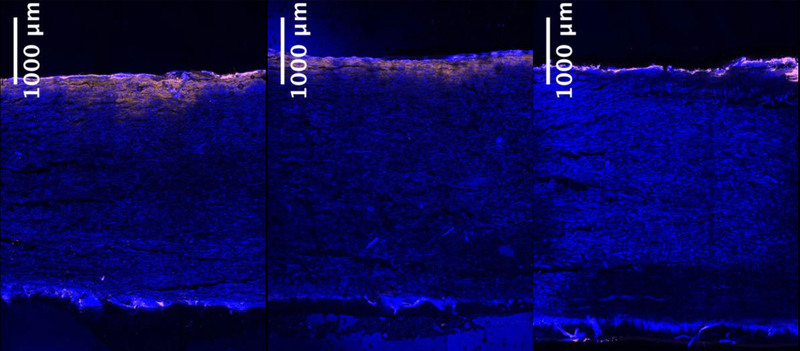

The retention of CHO chromosomal DNA was visualized by incorporating EdU into dividing adherent CHO-K1 cells and detecting it with 5-TAMRA azide. The cell lysate was centrifuged and the subsequent supernatant and the re-suspended pellet were loaded onto the 90ZB depth filter. Figures 8a, b and c show the retention profiles of the CHO-K1 lysate, its supernatant and pellet after re-suspension, on the 90ZB depth filter, respectively. DNA in the supernatant penetrates slightly into the filter, but similarly to pure DNA of a few kbp, the re-suspended pellet is retained strictly on the surface of the filter; the pellet appears rich in DNA. The surface retention of the resuspended pellet is explained by the size of the particles carrying the DNA, shown in Figure 9. Despite the heterogeneity in the particulates size, these are much larger than the depth filter’s nominal retention rating of 0.2 μm, which may include whole cells and cell debris. The mixture prior to centrifugation has the features seen in both the supernatant and the re-suspended pellet; a brighter band at the top (re-suspended pellet) with some DNA penetration into the filter (supernatant), as seen in Figure 8c. A qualitative comparison between the retention of purified CHO genomic DNA and CHO intracellular DNA suggests that DNA during harvest clarification is lengthy and cleared primarily through exclusion, although the concentration in the case of the DNA from the CHO culture was not controlled.

Figure 8.

Retention of CHO-K1 lysate, its supernatant and pellet after re-suspension, on the 90ZB depth filter are shown in (a), (b) and (c), respectively.

Figure 9.

Fluorescent particulates from the re-suspended pellet.

4. Conclusions

The visualization of the retained-DNA distribution on the 90ZB depth filter, shown here, provides information relating the length of DNA to its retention and capacity on the depth filter. Genomic DNA and longer lengths of DNA were found to be primarily retained on the surface and hence excluded from the interior of the filter, while short oligos are able to adsorb throughout the depth filter. The use of confocal microscopy allows for qualitative discrimination of retention – driven primarily by electrostatic interactions – from retention by size-based filtration. These findings provide another facet to the understanding of DNA clearance using depth filters, in that apart from the depth filters themselves, the properties of DNA, as an impurity, also impact its propensity to be retained on the depth filter. Furthermore, the greater penetration of the retained DNA on the depth filter with an increase in the buffer strength and the wash volume inform the impact of process parameter changes on DNA clearance. Labeled CHO intracellular DNA was also retained on the surface, suggesting that DNA during harvest clarification is either lengthy or exists within the debris and is cleared primarily through exclusion. Our experimental approach can be leveraged in investigating the current approaches to removal of DNA, whether in its form as an impurity or as a therapeutic product. The experimental design can potentially be used to study the retention kinetics of nucleic acids and other impurities on depth filters at a reasonably small scale. Furthermore, these findings can directly inform depth filter and operational parameter selection for efficient removal of DNA.

Highlights.

The mechanisms of retention of CHO DNA on depth filters were studied by visualization

Purified and intracellular DNA were loaded on depth filters in flow experiments

Retention was quantified by labeling and visualization using confocal microscopy

DNA retention is primarily by filtration, and a strong function of DNA length

DNA penetration increased with operational parameters such as wash volume

Acknowledgments

We grateful for the financial support provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) and for the depth filters provided by 3M Purification Development. We appreciate the guidance of Prof. Jeffery Caplan of the Bioimaging Center at the Delaware Biotechnology Institute and access to Prof. Christopher J. Roberts’s laboratory at the University of Delaware. The Bioimaging Center is supported in part by the NIH under grant number P20 GM103446. We further acknowledge Dr. Vijesh Kumar, Dr. Jing Guo and Stijn Koshari for helpful tips and discussions, Prof. Millicent Sullivan’s laboratory for providing the CHO-K1 cell line and cell culture laboratory access, Prof. Joseph M. Fox’s laboratory for providing the cloning vector and the Devens analytics group from BMS for analytical support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Smith SL, Ten years of Orthoclone OKT3 (muromonab-CD3): a review, Journal of Transplant Coordination 6 (1996) 109–119. doi: 10.1177/090591999600600304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wurm FM, Production of recombinant protein therapeutics in cultivated mammalian cells, Nature Biotechnology 22 (2004) 1393–1398. doi: 10.1038/nbt1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Petricciani JC, Horaud FN, DNA, dragons and sanity, Biologicals 23 (1995) 233–238. doi: 10.1006/biol.1995.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wierenga DE, Cogan J, Petricciani JC, Administration of tumor cell chromatin to immunosuppressed and non-immunosuppressed non-human primates, Biologicals 23 (1995) 221–224. doi: 10.1006/biol.1995.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Griffiths E, WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization - Highlights of the meeting of October 1996, Biologicals 25 (1997) 359–362. doi: 10.1006/biol.1997.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tauer C, Buchacher A, Jungbauer A, DNA clearance in chromatography of proteins, exemplified by affinity chromatography, Journal of Biochemical and Biophysical Methods 30 (1995) 75–78. doi: 10.1016/0165-022X(94)00058-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jiskoot W, Van Hertrooij JJCC, Klein Gebbinck JWTM, Van der Velden-de Groot T, Crommelin DJA, Beuvery EC, Two-step purification of a murine monoclonal antibody intended for therapeutic application in man. Optimisation of purification conditions and scaling up, Journal of Immunological Methods 124 (1989) 143–156. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(89)90196-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ng P, Mitra G, Removal of DNA contaminants from therapeutic protein preparations, Journal of Chromatography A 658 (1994) 459–463. doi: 10.1016/00219673(94)80036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yigzaw Y, Piper R, Tran M, Shukla AA, Exploitation of the adsorptive properties of depth filters for host cell protein removal during monoclonal antibody purification, Biotechnology Progress 22 (2006) 288–296. doi: 10.1021/bp050274w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Goerke AR, To BCS, Lee AL, Sagar SL, Konz JO, Development of a novel adenovirus purification process utilizing selective precipitation of cellular DNA, Biotechnology and Bioengineering 91 (2005) 12–21. doi: 10.1002/bit.20406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].White AF, Surface chemistry and dissolution kinetics of glassy rocks at 25°C, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta (1983). doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(83)90114-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [12].3M, 3M Solutions for Biopharmaceutical Process Development , Manufacturing and Process Monitoring, (2013). http://multimedia.3m.com/mws/media/493627O/3m-biopharmaceutical-catalog.pdf (accessed August 11, 2017).

- [13].Knight R, Ostreicher E, Charge-modified filter media, Filtration in the Biopharmaceutical Industry, Marcel Dekker, New York: (1998) 95–125. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Charlton HR, Relton JM, Slater NKH, Characterisation of a generic monoclonal antibody harvesting system for adsorption of DNA by depth filters and various membranes, Bioseparation 8 (1999) 281–291. doi: 10.1023/A:1008142709419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Singh N, Arunkumar A, Peck M, Voloshin AM, Moreno AM, Tan Z, Hester J, Borys MC, Li ZJ, Development of adsorptive hybrid filters to enable two-step purification of biologics, MAbs 9 (2017) 350–363. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2016.1267091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Murray K, Ang CE, Gull K, Hickman JA, Dickson AJ, NSO myeloma cell death: Influence of bcl-2 overexpression, Biotechnology and Bioengineering 51 (1996) 298–304. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wyllie AH, Glucocorticoid-induced thymocyte apoptosis is associated with endogenous endonuclease activation, Nature 284 (1980) 555–556. doi: 10.1038/284555a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Charlton HR, Relton JM, Slater NKH, DNA from clarified, large-scale, fed-batch, mammalian cell culture is of predominantly low molecular weight, Biotechnology Letters 20 (1998) 789–794. doi: 10.1023/B:BILE.0000015924.23815.c7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hiemenz PC, Rajagopalan R, Principles of colloid and surface chemistry, Marcel Dekker, New York: (1997). doi: 10.1016/0021-9797(79)90045-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chu B, Laser light scattering, Annual Review of Physical Chemistry 21 (1970) 145–174. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pc.21.100170.001045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Salic A, Mitchison TJ, A chemical method for fast and sensitive detection of DNA synthesis in vivo., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105 (2008) 2415–2420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712168105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Khanal O, Singh N, Traylor SJ, Xu X, Ghose S, Li ZJ, Lenhoff AM, Contributions of depth filter components to protein adsorption in bioprocessing, Biotechnology and Bioengineering 115 (2018): 1938–1948. doi: 10.1002/bit.26707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Smith DE, Perkins TT, Chu S, Dynamical scaling of DNA diffusion coefficients, Macromolecules 29 (1996) 1372–1373. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Latulippe DR, Zydney AL, Radius of gyration of plasmid DNA isoforms from static light scattering, Biotechnology and Bioengineering 107 (2010) 134–142. doi: 10.1002/bit.22787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Voordouw G, Kam Z, Borochov N, Eisenberg H, Isolation and physical studies of the intact supercoiled. The open circular and the linear forms of CoIE1-plasmid DNA, Biophysical Chemistry 8 (1978) 171–189. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(78)80008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Sanchez-Sevilla A, Thimonier J, Marilley M, Rocca-Serra J, Barbet J, Accuracy of AFM measurements of the contour length of DNA fragments adsorbed on mica in air and in aqueous buffer, Ultramicroscopy 92 (2002) 151–158. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3991(02)00128-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Borochov N, Eisenberg H, Kam Z, Dependence of DNA conformation on the concentration of salt, Biopolymers 20 (1981) 231–235. doi: 10.1002/bip.1981.360200116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hammermann M, Steinmaier C, Merlitz H, Kapp U, Waldeck W, Chirico G, Langowski J, Salt effects on the structure and internal dynamics of superhelical DNAs studied by light scattering and Brownian dynamics, Biophysical Journal 73 (1997) 2674–2687. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78296-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Garcia HG, Grayson P, Han L, Inamdar M, Kondev J, Nelson PC, Phillips R, Widom J, Wiggins PA, Biological consequences of tightly bent DNA: The other life of a macromolecular celebrity, Biopolymers 85 (2007) 115–130. doi: 10.1002/bip.20627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]