Introduction

Medicare spending is projected to grow at an average rate of 7.4% per year over the next decade. [1]. Because this growth rate threatens the Program’s solvency, a number of payment and delivery system reforms have been launched, most notably advanced payment models [e.g., payment bundling, accountable care organizations (ACOs)] and the patient-centered medical home. These programs are designed to reduce healthcare costs and improve (or at least maintain) quality. The collective focus of these reforms is on enhanced primary care for beneficiaries with multiple comorbid conditions. While such a focus is no doubt important, it turns a blind eye towards surgical care, which is not only a major source of morbidity and mortality among older adults, but also a large driver of healthcare resource consumption.

One possible reason is that the cost of surgical care is currently poorly understood. Older estimates suggest that inpatient surgical care represents nearly 50% of hospital expenditures and 30% of overall healthcare costs [2 3]. However, these estimates reflect only the care delivered during the initial hospitalization, and they fail to capture payments for expensive and common services that occur after discharge like those related to readmissions and post-acute care. Moreover, these estimates completely miss outpatient surgical episodes, encounters for which have risen rapidly over the last 20 years [4 5]. With the average American undergoing nine procedures during their lifetime [6], an accurate accounting of the costs of surgical care is needed.

In this context, we analyzed a nationally representative sample of Medicare data. After identifying beneficiaries who received surgical or procedural services, we measured payments made on their behalf during their inpatient and outpatient episodes of care. We then calculated total episode expenditures and assessed temporal trends in overall surgical spending. Finally, we examined spending trends outpatient status, site of care, and surgeon specialty. Findings from our study serve to inform policymakers and clinician leaders on where they are likely to find opportunities for reducing the costs of surgical care.

Methods

Data source and study population

For our study, we used medical claims from a 20% national sample of Medicare beneficiaries, including data from the Denominator, Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR), Outpatient, and Carrier research identifiable files (RIFs) for calendar years 2008 to 2014. To obtain an accurate accounting of perioperative care, we required beneficiaries to have continuous part A and B enrollment during a given surgical episode (defined below) for inclusion. We excluded beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans because services provided to them are inconsistently captured in their claims.

Identifying inpatient and outpatient surgical episodes

To determine whether a beneficiary received surgical or procedural services, we used Health Care Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes for surgery on the integumentary (10000–19999), musculoskeletal (20000–29999), respiratory (30000–32999), cardiovascular (33000–37799, 93451–93662), hemic and lymphatic Systems (38000–38999), mediastinum and diaphragm (39000–39999), digestive (40000–49999), urinary (50000–53999), male (54000–55899), and female genital (55900–58999), maternity care and delivery (59000–59999), endocrine (60000–60999), nervous (61000–64999), ocular (65000–68999), or auditory systems (69000–69999) to identify relevant claims in the Carrier RIF. For the remainder of our manuscript, we will refer to surgical and procedural care as surgical care.

Place of Service and Type of Service codes allowed us to distinguish between inpatient and outpatient procedures, as well as outpatient procedures carried out in hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs) versus ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) versus the physician office. We excluded beneficiaries whose surgical procedures took place in a skilled nursing facility (SNF) or extended-stay rehab facility. For measurement purposes, if a beneficiary underwent an outpatient procedure within 30 days of discharge from the surgical admission, we considered it part of the inpatient episode.

Calculating episode payments

To estimate the costs of surgical care, we first summed all payments for claims filed on a beneficiary’s behalf during the surgical episode. For inpatient procedures, we summed all payments for claims beginning 3 days prior to admission and extending 30 days after discharge. We further categorized the major components of payments, including those for the index hospitalization, readmissions, physician services, and post-acute care [7]. For each readmission, we identified whether it was planned or unplanned according to previous methods [8]. We treated planned readmissions as events distinct from the surgical episode and did not include payments associated with them in our estimates. Given that postoperative complications and planned readmissions are uncommon following outpatient procedures [9], we defined the outpatient surgical episode as including all claims for services delivered within a 24-hour window around the index outpatient procedure.

To determine the surgical specialty for which a given inpatient or outpatient episode was responsible, we used a plurality algorithm. Specifically, we summed up all payments during the episode by Medicare provider specialty codes (Appendix Table 1), attributing the episode to the specialty that billed for the largest amount. We then totaled all inpatient and outpatient episode payments by study year and surgical specialty. Since we were working with a 20% sample, we multiplied our totals by 5 to attain surgical cost estimates for all of Medicare fee-for-service. We inflation-adjusted payment data using the Consumer Price Index and express all totals in constant 2014 U.S. dollars [10].

Calculating total Program spending

To estimate total Program spending, we summed all payments for claims filed in the MedPAR, Carrier, and Outpatient RIFs by study year. For comparison to our surgical cohort, we used the same inclusion and exclusion criteria. Namely, Part A payments excluded those to a skilled nursing or extended-stay rehab facilities. Part B payments included payments made for office-based care, inpatient and outpatient hospital departments, and ASCs.

Statistical Analyses

For our initial analytic step, we plotted total, inpatient, and outpatient surgical payments in 2014 U.S. dollars over time. We then examined trends in component payments for inpatient surgery, site of care for outpatient surgery, surgical specialty, and total surgical payments by specialty. Finally, to determine statistical significance of these trends, we fit linear regression models, where our dependent variable was a specific payment type, and our independent variable was study year. We used SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC) for all analyses. Tests were two-tailed, and we set the probability of Type 1 error at 0.05. The University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board deemed our study to be exempt from its oversight.

Results

Over our study period, we identified a total of 78,830,444 surgical episodes, (93.4% and 6.6% of which were performed on an outpatient and inpatient basis, respectively). Table 1 characterizes our population at three time points, revealing that the sociodemographic characteristics and levels of comorbid illness among fee-for-service beneficiaries undergoing surgery were consistent across study years. Total Medicare payments for surgical care are substantial (Table 2). For instance, they represented 51% of Program spending in 2014. Figure 1 displays estimated annual Medicare payments for surgical care by study year. They declined over the study period, from $133.1 billion in 2008 to $124.9 billion in 2014 (−6.2%, P=0.085 for the temporal trend). The average payment per beneficiary declined over our study period from $7773 in 2008 to $7012 in 2014.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and number of co-morbidities, by year

| Characteristic | Calendar Year | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2011 | 2014 | |

| No. of eligible beneficiaries in the 20% sample | 6,150,919 | 6,345,803 | 6,536,797 |

| No. of surgical episodes | 10,761,714 | 11,191,878 | 11,681,672 |

| Average age at the time of surgery, in years (SD) | 74.4 (10.9) | 74.3 (11.1) | 74.2 (11.0) |

| % of patients undergoing surgery who were male (SE) | 44.6 (0.02) | 44.9 (0.01) | 45.3 (0.01) |

| % of patients undergoing surgery who were white (SE) | 89.3 (0.01) | 88.6 (0.01) | 88.4 (0.01) |

| Average HCC community score at the time of surgery (SD) | 1.48 (1.24) | 1.54 (1.30) | 1.54 (1.30) |

| No. of HCCs (SD) | 2.5 (2.3) | 2.6 (2.4) | 2.6 (2.4) |

| Average per capita income, in 1,000 USD (SD) | 40.2 (12.3) | 41.6 (12.0) | 46.2 (14.7) |

| % of population living below federal poverty limit (SE) | 13.1 (0.002) | 15.7 (0.002) | 15.2 (0.002) |

| No. of active MDs, per 10,000 population (SD) | 25.5 (18.4) | 25.9 (19.4) | 26.4 (19.7) |

Note. No., number; SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error; HCC, Hierarchical Condition Category

Table 2.

Overall annual surgical and non-surgical payments for Inpatient and Outpatient services

| Year | Inpatient | Outpatient | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | $ 138,416,693,835 | $ 100,430,641,760 | $ 238,847,335,595 |

| 2009 | $ 141,877,684,566 | $ 107,197,869,242 | $ 249,075,553,808 |

| 2010 | $ 140,374,476,212 | $ 109,759,269,602 | $ 250,133,745,814 |

| 2011 | $ 138,137,383,726 | $ 114,566,937,019 | $ 252,704,320,745 |

| 2012 | $ 125,908,595,152 | $ 115,953,734,019 | $ 241,862,329,171 |

| 2013 | $ 125,434,530,858 | $ 118,250,639,204 | $ 243,685,170,062 |

| 2014 | $ 123,001,302,975 | $ 121,104,227,965 | $ 244,105,530,940 |

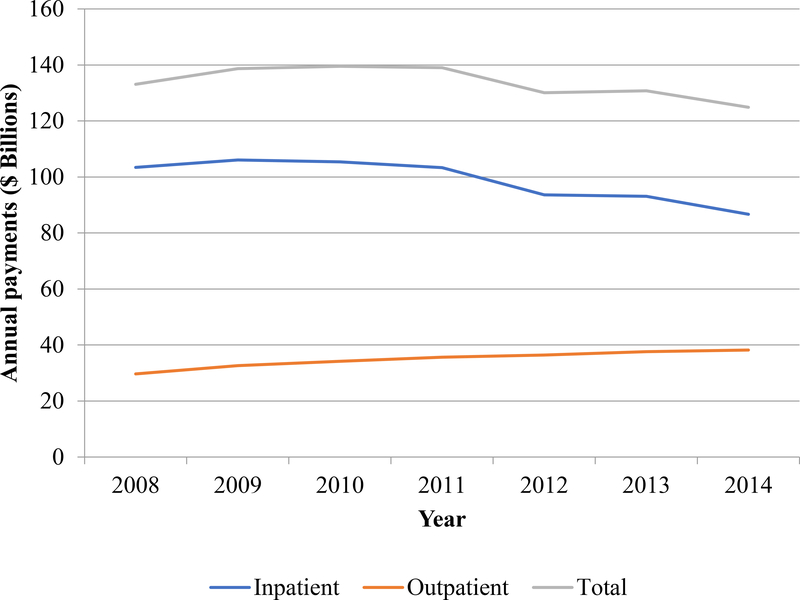

Figure 1.

Annual surgical payments (in $ Billions), by Inpatient and Outpatient procedures

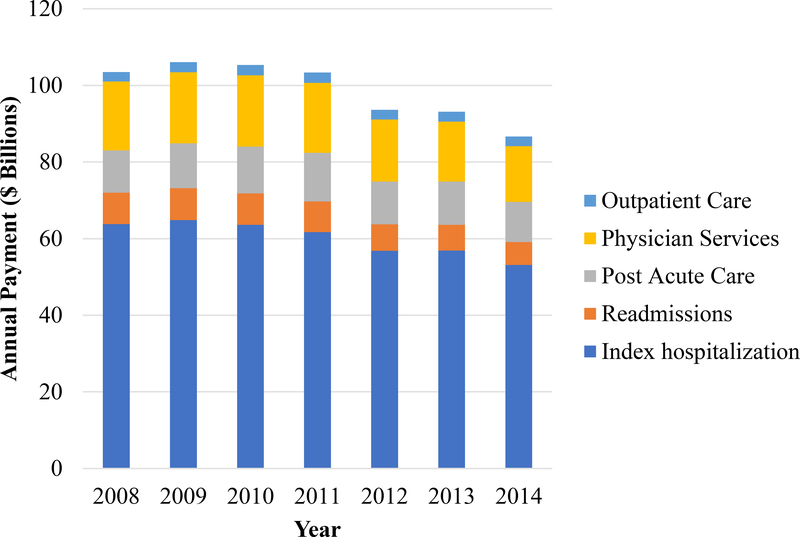

Figure 1 also shows that while payments for inpatient surgery declined, they still accounted for the majority of Medicare spending for surgery (69.4% in 2014). Payments for the index hospitalization were the largest single component of inpatient surgical spending, followed by payments for physician services, post-acute care, and readmissions. Figure 2 highlights that payments for the index hospitalization (−16.7%, P=0.002), readmissions (−27.0%, P=0.003), post-acute care services (−5.2%, P=0.40), and physician services (−18.9%, P=0.010) declined over the study period.

Figure 2.

Total annual outpatient surgical payments, by place of service

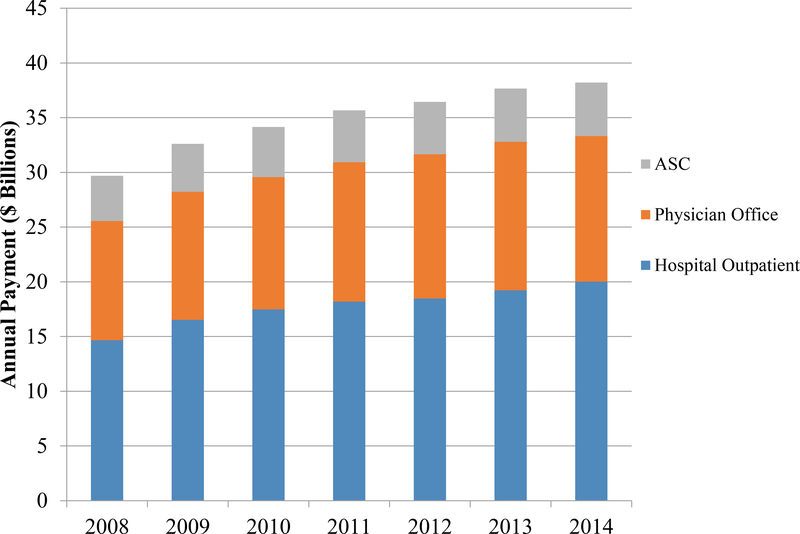

As opposed to spending on inpatient surgery, Figure 1 shows that payments for outpatient surgical care increased by $8.5 billion [28.7%, compound annual growth rate (CAGR) 3.7%] between 2008 and 2014 (P<0.001). In 2014, fifty-two percent of outpatient surgical spending was attributable to HOPDs, while services rendered in the physician office and ASCs represented 34.8% and 12.8%, respectively. Figure 3 illustrates that there was rapid growth in spending across all three of these sites over the study period. Specifically, payments for HOPDs, the physician office, and ASCs rose by 36.6% (CAGR 4.6%; P<0.001 for trend), 22.1% (CAGR 2.9%; (P<0.001), and 18.3% (CAGR 2.4%; P=0.001), respectively.

Figure 3.

Total annual inpatient surgical payments by component.

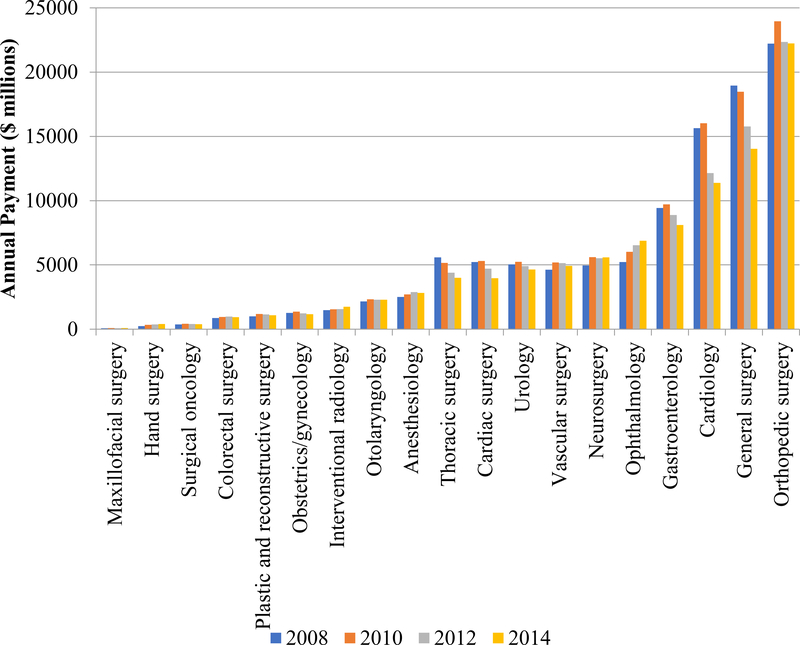

Figure 4 depicts total surgical payments by specialty. Orthopedic surgery and general surgery accounted for the greatest share of payments (17.8% and 11.2% in 2014, respectively). Payments for many specialties rose over the study period, with ophthalmology and hand surgery experiencing 2 of the largest increases (31.6%, and 70.5%, respectively) as shown on Figure 4. In contrast, payments for thoracic surgery and cardiology decreased sharply (−28.5% and −27.2%, respectively). Figure 4 also depicts that in contrast, payments for general surgery and cardiac surgery decreased sharply (−25.9% and −23.9% (CAGR −4.2% and −3.8%), respectively). While payments for inpatient procedures decreased across the majority of specialties, those for outpatient procedures increased across most specialties, with surgical oncology, interventional radiology, neurosurgery, and vascular surgery experiencing the greatest growth (Appendix Table 2).

Figure 4.

Total Annual Payments by Surgical Specialty

Discussion

Our study has 3 principal findings. As of 2014 Medicare payments for surgical care exceed $120 billion annually. Second, despite declines in inpatient surgical payments and total surgical payments, payments for outpatient surgery have increased across sites of care. Third, although payments for outpatient surgery are increasing for all specialties, most of its growth is concentrated among a handful. Collectively, these findings suggest that surgical spending is a key area for policymakers to target for savings.

Our analysis is the first to comprehensively evaluate Medicare spending on surgical care. The observed trends generally mirror those for the program as a whole, where rates of spending growth in outpatient care exceed that for inpatient services [11]. The shift from inpatient to outpatient spending is explained, in part, by advances in anesthesia and surgical techniques that have increased patient acceptance of outpatient surgery [12], as well as changes in reimbursement that encourage care delivery in the outpatient setting [13]. Our findings on differences between specialties in their affinity for outpatient surgery are also consistent with all-payer data from Florida [14]. Importantly, the complexity of patients as shown in Table 1 did not change significantly over the study period. Thus there is a low likelihood that a changing Medicare population biased our study results.

Our study has several limitations that merit further discussion. First, our analysis was based entirely on Medicare data. As such, the observed spending patterns may not be generalizable to commercial insurers. That said, the Medicare program accounted for 19.2% and 20% of all healthcare spending in the United States in 2008 and 2014 respectively [15]. Second, while we defined surgical episode lengths using standards from the literature, we acknowledge that some relevant spending may fall outside of the claims windows for inpatient and outpatient surgery that we used [9]. Therefore, our spending totals may underestimate actual Medicare spending on surgery. Third, our analysis only captures payments made by Medicare, missing other direct and indirect costs associated with surgical care. After 65 years of age beneficiaries may have supplemental insurance coverage; therefore, expenditures in our analysis may be underestimating the total cost of surgical care. Nonetheless, our focus is important from a payment policy perspective. Fourth, the payment data that we analyzed are from the Medicare Fee-for-Service population only. Due to inconsistent capture of claims for Medicare Advantage enrollees, we had to exclude these beneficiaries from our analyses. Given that there has been considerable growth in Medicare Advantage enrollment (representing 30% of overall Medicare in 2014), total Program spending on surgical and procedural care is anticipated to be higher than what we report. That said, the case mix stability that we observed suggest that we did not bias our population with this exclusion.

These limitations notwithstanding, our findings serve to inform decision makers at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Some of the decline in inpatient spending relates to decreasing payments for readmissions, likely owing to spillover effects from the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program [16–18]. Although joint replacement and coronary artery bypass grafting recently became targeted conditions, the inclusion of other surgical service lines could help reduce spending on inpatient surgery further. To tackle outpatient spending, CMS could extend inpatient episode-based bundling programs, such as the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative, to outpatient surgical procedures.

More broadly, CMS may want to better integrate surgeons into their value-based purchasing programs. For instance, perioperative surgical homes, in which surgeons and anesthesiologists play key roles in care coordination, have been shown to lower surgical costs, while increasing patient satisfaction [19]. Alternatively, CMS might encourage more surgeon participation in Medicare ACOs [20]. If surgeons participating in an ACO reduce their expenditures below benchmarks, they are rewarded with a portion of the savings. To the extent that such shared savings motivate surgeons to lower their treatment costs, they may limit their procedure use, lowering spending.

Conclusions

In summary, our findings demonstrate that Medicare’s spending on surgical care is substantial, exceeding $120 billion annually and accounting for approximately 51% of Program spending in 2014. Moreover, they highlight the greatest growth in payments and therefore potential opportunities, especially around outpatient surgery, for CMS to rein in costs. Moving forward, future research should evaluate the extent to which spending on outpatient surgical care is driven by discretionary (versus non-discretionary) procedures. A better understanding of this will aid in the design of interventions to reduce surgery spending.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality (1R01HS024525 01A1 and 1R01HS024728 01 to JMH), the National Institute on Aging (R01-AG-048071 to BKH), and the National Cancer Institute (5-T32-CA-180984–03 to DRK).

Appendix Table 1:

Medicare provider specialty codes and specialty group cross-walk

| HCFA Specialty Code | Description | Specialty Group | Specialty Group Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 00 | Carrier wide | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 01 | General practice | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 02 | General surgery | 02 | General surgery |

| 03 | Allergy/immunology | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 04 | Otolaryngology | 04 | Otolaryngology |

| 05 | Anesthesiology | 05 | Anesthesiology |

| 06 | Cardiology | 06 | Cardiology |

| 07 | Dermatology | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 08 | Family practice Interventional Pain Management (IPM) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 09 | (eff. 4/1/03) | 05 | Anesthesiology |

| 10 | Gastroenterology | 10 | Gastroenterology |

| 11 | Internal medicine | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 12 | Osteopathic manipulative therapy | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 13 | Neurology | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 14 | Neurosurgery | 14 | Neurosurgery |

| 15 | Obstetrics (osteopaths only) (discontinued 5/92 use code 16) | 16 | Obstetrics/gynecology |

| 16 | Obstetrics/gynecology | 16 | Obstetrics/gynecology |

| 17 | Ophthalmology, otology, laryngology, rhinology (osteopaths only) (discontinued 5/92 use codes 18 or 04 depending on percentage of practice) | 18 | Ophthalmology |

| 18 | Ophthalmology | 18 | Ophthalmology |

| 19 | Oral surgery (dentists only) | 85 | Maxillofacial surgery (eff 5/92) |

| 20 | Orthopedic surgery | 20 | Orthopedic surgery |

| 21 | Pathologic anatomy, clinical pathology (osteopaths only) (discontinued 5/92 use code 22) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 22 | Pathology | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 23 | Peripheral vascular disease, medical or surgical (osteopaths only) (discontinued 5/92 use code 76) | 77 | Vascular surgery (eff 5/92) |

| 24 | Plastic and reconstructive surgery | 24 | Plastic and reconstructive surgery |

| 25 | Physical medicine and rehabilitation | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 26 | Psychiatry | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 27 | Psychiatry, neurology (osteopaths only) (discontinued 5/92 use code 86) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 28 | Colorectal surgery (formerly proctology) | 28 | Colorectal surgery (formerly proctology) |

| 29 | Pulmonary disease | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 30 | Diagnostic radiology | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 31 | Roentgenology, radiology (osteopaths only) (discontinued 5/92 use code 30) Anesthesiologist Assistants (eff. 4/1/03--previously grouped with | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 32 | Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists (CRNA)) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 33 | Thoracic surgery | 33 | Thoracic surgery |

| 34 | Urology | 34 | Urology |

| 35 | Chiropractic | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 36 | Nuclear medicine | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 37 | Pediatric medicine | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 38 | Geriatric medicine | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 39 | Nephrology | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 40 | Hand surgery | 40 | Hand surgery |

| 41 | Optometry (revised 10/93 to mean optometrist) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 42 | Certified nurse midwife (eff 1/87) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 43 | CRNA (eff. 1/87) (Anesthesiologist Assistants were removed from this specialty 4/1/03) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 44 | Infectious disease | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 45 | Mammography screening center | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 46 | Endocrinology (eff 5/92) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 47 | Independent Diagnostic Testing Facility (IDTF) (eff. 6/98) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 48 | Podiatry | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 49 | Ambulatory surgical center (formerly miscellaneous) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 50 | Nurse practitioner | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 51 | Medical supply company with certified orthotist (certified by American Board for Certification in Prosthetics And Orthotics) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 52 | Medical supply company with certified prosthetist (certified by American Board for Certification In Prosthetics And Orthotics) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 53 | Medical supply company with certified prosthetist- orthotist (certified by American Board for Certification in Prosthetics andOrthotics) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 54 | Medical supply company not included in 51, 52, or 53. (Revised 10/93 to mean medical supply company for DMERC) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 55 | Individual certified orthotist | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 56 | Individual certified prosthetist | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 57 | Individual certified prosthetist-orthotist | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 58 | Individuals not included in 55, 56, or 57, (revised 10/93 to mean medical supply company with registered pharmacist) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 59 | Ambulance service supplier, e.g., private ambulance companies, funeral homes, etc. | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 60 | Public health or welfare agencies (federal, state, and local) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 61 | Voluntary health or charitable agencies (e.g. National Cancer Society, National Heart Association, Catholic Charities) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 62 | Psychologist (billing independently) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 63 | Portable X-ray supplier | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 64 | Audiologist (billing independently) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 65 | Physical therapist (private practice added 4/1/03) (independently practicing removed 4/1/03) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 66 | Rheumatology (eff 5/92) Note: during 93/94 DMERC also used this to mean medical supply company with respiratory therapist | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 67 | Occupational therapist (private practice added 4/1/03) (independently practicing removed 4/1/03) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 68 | Clinical psychologist | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 69 | Clinical laboratory (billing independently) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 70 | Multispecialty clinic or group practice | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 71 | Registered Dietician/Nutrition Professional (eff. 1/1/02) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 72 | Pain Management (eff. 1/1/02) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 73 | Mass Immunization Roster Biller (eff. 4/1/03) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 74 | Radiation Therapy Centers (added to differentiate them from Independent Diagnostic Testing Facilities (IDTF -eff. 4/1/03) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 75 | Slide Preparation Facilities (added to differentiate them from Independent Diagnostic Testing Facilites (IDTFs -eff. 4/1/03) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 76 | Peripheral vascular disease (eff 5/92) | 77 | Vascular surgery (eff 5/92) |

| 77 | Vascular surgery (eff 5/92) | 77 | Vascular surgery (eff 5/92) |

| 78 | Cardiac surgery (eff 5/92) | 78 | Cardiac surgery (eff 5/92) |

| 79 | Addiction medicine (eff 5/92) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 80 | Licensed clinical social worker | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 81 | Critical care (intensivists) (eff 5/92) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 82 | Hematology (eff 5/92) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 83 | Hematology/oncology (eff 5/92) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 84 | Preventive medicine (eff 5/92) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 85 | Maxillofacial surgery (eff 5/92) | 85 | Maxillofacial surgery (eff 5/92) |

| 86 | Neuropsychiatry (eff 5/92) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 87 | All other suppliers (e.g. drug and department stores) (note: DMERC used 87 to mean department store from 10/93 through 9/94; recoded eff 10/94 to A7; NCH cross-walked DMERC reported 87 to A7. | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 88 | Unknown supplier/provider specialty (note: DMERC used 87 to mean grocery store from 10/93 – 9/94; recoded eff 10/94 to A8; NCH cross- walked DMERC reported 88 to A8. | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 89 | Certified clinical nurse specialist | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 90 | Medical oncology (eff 5/92) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 91 | Surgical oncology (eff 5/92) | 91 | Surgical oncology (eff 5/92) |

| 92 | Radiation oncology (eff 5/92) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 93 | Emergency medicine (eff 5/92) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 94 | Interventional radiology (eff 5/92) | 94 | Interventional radiology (eff 5/92) |

| 95 | Competative Acquisition Program (CAP) Vendor (eff. 07/01/06). Prior to 07/01/06, known as Independent physiological laboratory (eff. 5/92) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 96 | Optician (eff 10/93) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 97 | Physician assistant (eff 5/92) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| 98 | Gynecologist/oncologist (eff 10/94) | 16 | Obstetrics/gynecology |

| 99 | Unknown physician specialty | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| A0 | Hospital (eff 10/93) (DMERCs only) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| A1 | SNF (eff 10/93) (DMERCs only) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| A2 | Intermediate care nursing facility (eff 10/93) (DMERCs only) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| A3 | Nursing facility, other (eff10/93) (DMERCs only) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| A4 | HHA (eff 10/93) (DMERCs only) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| A5 | Pharmacy (eff 10/93) (DMERCs only) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| A6 | Medical supply company with respiratory therapist (eff 10/93) (DMERCs only) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| A7 | Department store (for DMERC use: eff 10/94, but cross- walked from code 87 eff 10/93) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| A8 | Grocery store (for DMERC use: eff 10/94, but cross- walked from code 88 eff 10/93) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| A9 | Indian Health Service (IHS), tribe and tribal organizations (nonhospital or nonhospital based facilities. DMERC s shall process claims submitted by IHS, tribe and nontribal organizations for DMEPOS and drugs covered by the DMERCs. (eff. 1/2005) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| B1 | Supplier of oxygen and/or oxygen related equipment (eff. 10/2/07) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| B2 | Pedorthic Personnel (eff. 10/2/07) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| B3 | Medical Supply Company with Pedorthic Personnel (eff. 10/2/07) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

| B4 | Rehabilitation Agency (eff. 10/2/07) | ZZ | Non-surgical specialty |

Appendix Table 2:

Percent change in total, inpatient, and outpatient payments by specialty

| Total | Inpatient | Outpatient | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anesthesiology | 12.5% | −30.8% | 45.0% |

| Cardiac surgery | −23.9% | −24.5% | 9.2% |

| Cardiology | −27.2% | −39.3% | 22.4% |

| Colorectal surgery | 7.0% | 3.9% | 26.7% |

| Gastroenterology | −14.2% | −22.3% | 13.3% |

| General surgery | −25.9% | −31.1% | 11.8% |

| Hand surgery | 70.5% | 51.0% | 92.7% |

| Interventional radiology | 18.3% | 5.8% | 88.5% |

| Maxillofacial surgery | 16.9% | 9.4% | 31.7% |

| Neurosurgery | 12.7% | 7.9% | 97.8% |

| Obstetrics/gynecology | −7.5% | −35.7% | 61.6% |

| Ophthalmology | 31.6% | −34.5% | 32.4% |

| Orthopedic surgery | 0.1% | −1.3% | 14.6% |

| Otolaryngology | 6.4% | −19.5% | 46.5% |

| Plastic and reconstructive surgery | 7.8% | −5.8% | 30.9% |

| Surgical oncology | 4.9% | −6.8% | 88.4% |

| Thoracic surgery | −28.5% | −29.0% | −6.5% |

| Urology | −8.0% | −18.7% | 3.7% |

| Vascular surgery | 6.2% | −5.7% | 105.5% |

| Unknown physician specialty | 66.9% | 70.1% | 17.8% |

| Non-surgical specialty | 6.0% | −6.5% | 33.0% |

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

JBD: ArborMetrix, Inc – Ownership Interest

References

- 1.CMS. NHE Projections: Table 04 Health Consumption Expenditures by Source of Funds, 2017. Accessed: 28 January, 2018 Available at: https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nhe-fact-sheet.html

- 2.Health Care Cost Institute. Health Care Cost and Utilization Report: 2010. Accessed: 13 April, 2018 Available at: http://www.healthcostinstitute.org/files/HCCI_HCCUR2010.pdf

- 3.Munoz E, Munoz W 3rd, Wise L National and surgical health care expenditures, 2005–2025. Annals of surgery 2010;251(2):195–200 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181cbcc9a[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cullen KA, Hall MJ, Golosinskiy A. National Health Statstics Report: Ambulatory Surgery in the United States, 2006. Accessed: 9 January, 2018 Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr011.pdf. [PubMed]

- 5.Hollenbeck BK, Dunn RL, Suskind AM, Zhang Y, Hollingsworth JM, Birkmeyer JD. Ambulatory surgery centers and outpatient procedure use among Medicare beneficiaries. Medical care 2014;52(10):926–31 doi: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000213[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee P, Regenbogen S, Gawande AA. How many surgical procedures will Americans experience in an average lifetime?: Evidence from three states, 2018. Accessed: 28 January, 2018 Available at: http://www.mcacs.org/abstracts/2008/P15.cgi.

- 7.Birkmeyer JD, Gust C, Baser O, Dimick JB, Sutherland JM, Skinner JS. Medicare payments for common inpatient procedures: implications for episode-based payment bundling. Health services research 2010;45(6 Pt 1):1783–95 doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01150.x[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.CMS. 2017 All-Cause Hospital-Wide Measure Updates and Specifications. Report: Hospital-Level 30-Day Risk-Standardized Readmission Measure – Version 6.0, 2017. Accessed: 28 January, 2018 Available at: file:///Users/kayed/Downloads/2017_HWR_Rdmsn_MUS_Rpt%20(2).pdf

- 9.Hollingsworth JM, Saigal CS, Lai JC, et al. Medicare payments for outpatient urological surgery by location of care. The Journal of urology 2012;188(6):2323–7 doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.031[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bureau of Labor Statistics. CPI Inflation Calculator, 2018. Accessed: March 13, 2018 Available at: https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm.

- 11.MEDPAC. Report to Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, 2017. Accessed 12 march, 2018 Available at: http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar17_entirereport.pdf

- 12.Warner MA, Shields SE, Chute CG. Major morbidity and mortality within 1 month of ambulatory surgery and anesthesia. Jama 1993;270(12):1437–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medicare Program Health Care Financing Administration. Fee schedule for physician services: Final notice. Federal Register 1991;56:59577–87,635 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollingsworth JM, Birkmeyer JD, Ye Z, Miller DC. Specialty-specific trends in the prevalence and distribution of outpatient surgery: implications for payment and delivery system reforms. Surgical innovation 2014;21(6):560–5 doi: 10.1177/1553350613520515[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CMS. National Health Expenditures 2016 Highlights 2017. Accessed: 9 January, 2018 Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/Downloads/highlights.pdf

- 16.Borza T, Oerline MK, Skolarus TA, et al. Association of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program With Surgical Readmissions. JAMA surgery 2017. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.4585[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Desai NR, Ross JS, Kwon JY, et al. Association Between Hospital Penalty Status Under the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program and Readmission Rates for Target and Nontarget Conditions. Jama 2016;316(24):2647–56 doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.18533[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zuckerman RB, Sheingold SH, Orav EJ, Ruhter J, Epstein AM. Readmissions, Observation, and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. The New England journal of medicine 2016;374(16):1543–51 doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1513024[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kash BA, Zhang Y, Cline KM, Menser T, Miller TR. The perioperative surgical home (PSH): a comprehensive review of US and non-US studies shows predominantly positive quality and cost outcomes. The Milbank quarterly 2014;92(4):796–821 doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12093[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawken SR, Ryan AM, Miller DC. Surgery and medicare shared savings program accountable care organizations. JAMA surgery 2016;151(1):5–6 doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.2772[published Online First: Epub Date]|. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.CMS. National Health Expenditures 2014 Highlights 2015. Accessed: 24 January, 2018 Avaialble at: https://ccf.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/highlights.pdf

- 22.CMS. Table 05–5 Medicare Spending by Sponsor, 2017. Accessed: 28 January, 2018 Available at: https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nhe-fact-sheet.html.