INTRODUCTION

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a prominent example of existing health disparities for American Indians. Compared to all other racial and ethnic populations, American Indians have the highest prevalence of T2DM, over twice that of Whites (15% versus 7%),1 with T2DM treatment accounting for over a third of all of the Indian Health Services’ medical costs.2 American Indians also experience T2DM-related health complications two to four times higher that of their White counterparts,3 with T2DM-related mortality rates 1.6 times higher among American Indians of all ages compared to the general U.S. population.4

One of the key components of T2DM self-management includes adoption of and adherence to a healthy balanced diet. Nutrition therapy recommendations for individuals with T2DM include limiting the amount of foods high in fat, sugar, and sodium, and increasing intake of foods rich in nutrients, such as fruits and vegetables.5 However, the adoption of healthier eating patterns is highly dependent on the knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes regarding the role of diet in T2DM self-management.6

It is important to seek an understanding of contextual factors that influence dietary beliefs and practices among persons with T2DM among different racial and ethnic populations. Few known studies have examined dietary beliefs and management practices as it relates to T2DM among American Indian adults of all ages. One study surveyed 219 Lakota Indian adults residing on two adjacent reservations in South Dakota.7 Of this sample, 86% agreed that T2DM was related to what people ate. Regarding specific desirable dietary practices, 90% indicated reducing the amount of food eaten, 86% indicated eating more fruits and vegetables, and 79% indicated reducing high-fat food consumption.7 A second study with 203 urban American Indian women with unknown T2DM status revealed that 91% hold beliefs that dietary practices are related to T2DM. Regarding specific dietary practices, 79% tried to eat more fruits and vegetables, 70% reduced the amount of food consumed, and 62% eliminated snack foods.8 A third study with 20 American Indian men participants, of whom 35% had T2DM, implicated poor dietary practices as the one of the primary ways to both prevent and manage T2DM.9 Many participants also identified higher cost of healthier foods and inconvenience of maintaining a healthy diet as significant barriers to long-term healthier eating patterns. Based on the findings from these three studies, it appears that overall American Indians appreciate the role of diet in T2DM prevention and self-management which contributes to the adoption of healthier diets. Yet, there are also notable barriers that can impede one’s success in maintaining healthier eating patterns.

A recently published study of older American Indians with T2DM examined their T2DM-related beliefs, attitudes, and practices including diet. With regards to dietary beliefs, participants expressed that food was a central feature of community social gatherings.10 No other publications have examined dietary beliefs among older American Indians with T2DM. This is surprising as aging, race/ethnicity, and diet are main risk factors for T2DM and older adults have the highest percent of T2DM with 25% of persons aged ≥ 65 years having T2DM.11 Overall, research findings have identified generational differences in food consumption and related-beliefs. For instance, older Hispanic mothers were less acculturated and ate less fat and had higher vegetable/fruit/fiber intake than their daughters.12 With a mixed race and ethnicity sample of adults at eight community health centers, older adults compared to younger adults were less likely to endorse behavioral factors such as diet and exercise as causes of body weight.13 An examination of the American Indians Diabetes Prevention Demonstration Project participants found that retired American Indians and Alaska Natives were more likely to select healthy foods more frequently compared to their non-retired counterparts.14 Thus, inquiry focusing on older adults is important to identify and understand dietary beliefs and practices among American Indians. Improving our understanding of this will only become more relevant for practitioners since, between 2012 and 2050, the number of American Indians aged ≥ 65 years is estimated to increase nearly four-fold, from 266,000 to 996,000.15 The prevalence of T2DM is substantially higher among those in the study’s participating tribe with 60% of tribal members aged ≥ 65 years having T2DM.16 Thus, the aim of this study was to qualitatively examine the dietary beliefs and dietary self-management practices among older American Indians with T2DM.

Two theoretical frameworks helped to guide this study, including the social constructivist theory17,18 and explanatory models of illness.19 The social constructivist perspective explains that knowledge is generated and interpreted collectively through shared language and experiences, and thus individuals make sense and meaning from their experiences.18 With this perspective, the investigative team considered participants’ beliefs through the framework and context of the tribal community. The explanatory models of illness framework explain how cultural groups make sense of illnesses and have culturally distinct ways of responding to illnesses that are intimately related to shared beliefs, values, and behavioral norms.19 This framework directed the investigative team to assess on how participants’ understood their own illnesses and how they responded to it.

METHODS

Study Design

This study was guided by community-engagement research principles20 and the examination of T2DM was in response to it being the top health priority for the participating tribe. A low-inference qualitative descriptive methodology was used where the aim is to use a pragmatic approach that is a straight description of an experience.22 This methodology allowed the investigative team to understand individual and community perspectives regarding diet and T2DM. Examining American Indians’ perspectives can help improve the understanding of how they live with T2DM and how living in community spaces influence dietary practices.

Study Participants

Study participation was invited from among those who participated in the Native Elder Care Study, which was conducted with the same tribe. The Principal Investigator (PI) of the Native Elder Care Study has over 18 years of experience working with this tribe and its older members. The Native Elder Care Study was a cross-sectional study of 505 non-institutionalized adults aged ≥ 55 years who were members of a federally recognized American Indian tribe. Inclusion criteria included being a tribal member, aged ≥ 55 years, noninstitutionalized, cognitively intact, and reside in the tribe’s service area. Greater detail about the Native Elder Care Study’s methodology is described elsewhere.20

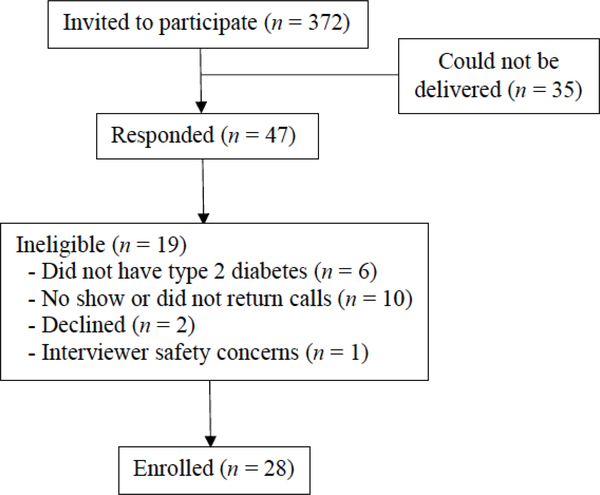

For the present study, a purposive sampling method was used. Study eligibility included being a participant in the Native Elder Care Study, residing in the tribe’s service area, and having self-reported T2DM. Participation was solicited through mailed letters to the Native Elder Care Study cohort who were still alive and had indicated that they had T2DM. Death information for the Native Elder Care Study cohort was obtained from public state death records. The letter provided the study objectives and a local telephone number of the PI. As shown in the Figure, the first mailing was sent to 372 persons and a second mailing was sent 15 days later, removing those who had already responded and those whose first letter could not be delivered (n = 35). A total of 47 interested participants responded to the letters and 28 ultimately participated. Among the 19 who did not participate, six did not have T2DM. Ten did not show to a scheduled interview, canceled a scheduled interview, or did not return calls. Two were married but declined participation because their interviews could not be conducted together. Finally, a scheduled interview was not conducted due to the interviewer’s safety concerns.

Figure.

Study Consort Flow Chart

Data Collection

Data were collected with a semi-structured qualitative interview guide, which was developed primarily with input from the Community Advisory Board (CAB) members and the research literature. The study questions and design emerged from ongoing discussions with the project’s CAB, which was assembled based on the PI’s prior experience conducting research with the participating tribe. An interview guide was piloted with a convenience sample of six tribal members (4 women, 2 men) who were aged ≥ 60 years and had self-reported T2DM. The study’s PI conducted the piloted interviews accompanied by a graduate student for their training purposes. The investigative team discussed the feedback obtained from the piloted interviews and revised the interview guide accordingly. Specifically, the interview guide was modified by adding in additional probes, reordering of questions, rephrasing the question regarding emotional experiences, and adding five new questions. The final interview guide consisted of 19 main questions with probes (see Table). Age and gender of the participants were obtained through the Native Elder Care Study data; current marital status was obtained during the qualitative interview.

Table.

Interview Guide

| 1. How long have you had type 2 diabetes? |

| 2. What do you think about having diabetes? |

| 3. What is different between those who get diabetes and those who don’t in the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians? |

| 4. What do you think caused your diabetes? Probes: How did it make you feel when you were first diagnosed? How does it make you feel now? Do you feel as though you were going to get it no matter what you did? |

| 5. How confident do you feel that you can successfully manage your diabetes on a scale from 1 to 10 with 1 representing no confidence and 10 representing the greatest confidence? |

| 6. How do you manage your diabetes on a daily basis? Probes: What things do you do well? Can you share an example? What helps and how? What things do you not do so well? |

| 7. Overall, would you say that your diabetes is well-managed or poorly managed? |

| 8. Can you share a time when you knew your diabetes was not as well managed as it could be? |

| 9. What are the primary factors or reasons why you say your diabetes is well-managed/poorly managed? |

| 10. Among those who have diabetes in the tribe, what do those people with well-managed/poorly managed diabetes do differently than you? |

| 11. Who helps you with your diabetes? Probes: Do you have strong social support with respect to your diabetes management? |

| 12. What is the value in managing your diabetes well? |

| 13. What are the consequences of not managing your diabetes well? |

| 14. How do your feelings, such as feeling down, or tired, or out of energy, affect your ability to manage your diabetes? |

| 15. What is it that you wish others understood about your diabetes? |

| 16. Is there anything you need that you don’t already have to better manage your diabetes? |

| 17. Other than what the doctor has told you and what you have learned from experience, is there a Cherokee way to deal with your diabetes? |

| 18. In general, what are the factors that you believe that contribute to good diabetes control? |

| 19. Are there any other thoughts you have about your diabetes and your ability manage it that you would like to share? |

Twenty-eight interviews were conducted in fall 2015 by the study’s PI and a graduate student. Each interview, lasting 48 minutes on average, was conducted individually and face-to-face either in participant’s homes or at a private office setting. All interviews were digitally audio-recorded and professionally transcribed. Transcriptions were audited for completeness and accuracy by two of the study investigators. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, who received $75 for their participation. Approval for this study was obtained from the tribe’s institutional review board (IRB), tribe’s health board, and tribal council. The PI’s academic home and the tribe signed an IRB authorization agreement, which permitted the academic institution to cede review to the tribal IRB.

Analyses

All analyses were informed by a qualitative analysis expert (JJ). Using NVivo qualitative data management software (Version 11), qualitative thematic content analysis was performed primarily by one team member and corroborated by two other members through reflexive and iterative team consensus discussions. Thematic content analysis is a low-inference interpretive technique where researchers derive valid and reliable contextual meaning in a systematic manner from qualitative data that originated from open-ended interviews.23 The analytic team consisted of three investigators from the fields of nursing, gerontology, and public health and with experience in both qualitative and community-based participatory research. Specifically, thematic analysis was used to openly and inductively code in vivo text and to derive themes regarding participants’ T2DM-related dietary beliefs and dietary management. As noted, the description, naming, and interpretation of themes was an iterative team process. This type of thematic work is interpretive in nature and grounded in team understanding rather than interrater reliability analysis.

Analyses were completed for the first 28 participants when coding suggested that informational saturation of content had been achieved. Specifically, saturation was determined when interviewees were no longer offering new ideas, no more patterns were emerging from the data, and further coding was not effective.24,25 Several strategies were used to ensure trustworthiness. The interview data was triangulated through comparison with debriefing discussions with CAB members to test potential transferability of contextual interpretations. A detailed audit trail was also maintained through audio recordings and note taking of decisions, discussions, theme development, and the refinement of analyses and procedures.26

RESULTS

For the 28 interviewees, the age range was 61 to 89 years with a mean of 73.0 ± 6.4 years; slightly more than half (57%, n = 16) were women; half (n = 14) were married. Four themes with respect to T2DM-related dietary beliefs and self-management practices emerged from the analyses, which included: (1) diet changes, (2) portion control, (3) healthcare professional and family influence, and (4) barriers to healthy eating.

Diet Changes

A diagnosis of T2DM was viewed by study participants as a significant cue to change their diets, which included the types of food they typically ate and the way these foods were prepared. A female participant referred to cutting back on cooking fried foods: “I don’t fix a lot of greasy food anymore. I try to do a lot of baking the food, the chicken, the meat, grilling.” Fatback, fat that is from the back of a pig, was commonly referred to among participants as a type of food to cut back on. Another female participant stated: “I don’t eat fatback anymore because I know it’s a bad fat.” As expressed by two male participants, cutting back on sugar and salt were also identified as important changes in individuals’ diet.

She obviously cut back on the – when she bakes a cake, she cuts back. She don’t put as much sweetening in it. She makes more of a diabetic cake when she does it because she herself don’t like too much sweetness.

I’ve cut down on salt. A lot of people just add the salt the first thing when they start eating. I just take it as it’s given to me and I don’t add no salt to it or nothing like that. I use the non-sugar fake diet drinks all of the time. I use the Splenda or sweeteners.

Finally, a male participant described the change of diet since their T2DM diagnosis as the need to eliminate foods high in carbohydrates and to eat more salads and vegetables:

I remember getting more steamed vegetables and stuff that was boiled rather than grilled. I remember the emphasis was more on salads and vegetables, which I do still eat mostly salads, and not as much – or not any really – carbohydrates like baked potatoes, or mashed potatoes and gravy, which I had quite a bit of before. Bean bread and chestnut bread no longer.

Portion Control

Portion control is eating a healthy balance of amount and types of varied food within a certain dietary pattern. It is also knowing how much a serving size of food or beverage is and how many calories a serving contains. Two female participants illustrated their rationale for food portioning:

I have learned through all these years that it’s not really what you eat, but the amount that you put in that can’t either process fast enough and builds up as sugar or what. But if you eat a little bit, all the processes just keep working normal.

I watch what I eat and I check my blood sugars. I know as soon as I pick up something [that] I’m not supposed to have, I know that if I get too much of it then I’m going to pay for it, so I try to cut it down to about a piece of cake. I’ll cut it down. I say cut me off just a sliver. I make it last. I eat it slow.

Another two female participants discussed cutting back on sugary drinks and replacing them with water:

I don’t buy as many drinks now because that’s a temptation if I have them in the fridge, and then end up screaming my name. So I go and get cases of water, and my coffee….I put it all on portion control, exercising, watching what you eat, eat more veggies and fruits, and a lot of greens, and lay off a lot of that meat.

That’s what scares me too is I know I need to get myself in better condition and better shape so I don’t have to go on dialysis and I try not to drink a whole lot of sodas.

Healthcare Professional and Family Influence

Participants offered ways in which they incorporated what they learned from healthcare professionals about dietary management of T2DM. A female participant expressed “Now fruits, we love fruit... but they told me at the diabetic clinic, ‘Well, the fruit has sugar too. You shouldn’t be eating too many fruits.’” Several male participants stated that their spouses would act as a facilitator for better dietary management. Two quotes exemplify this:

I call my wife a caretaker because in regard to what you should do, that’s why I do everything I should do, and I monitor everything completely. It’s because she does make sure I do all of those above.

My wife….If I didn’t have her, I’d be dead. It’s obvious. There again, every good relationship, you decide what you’re best at. Definitely in this case, she’s best at maintaining and taking care of my health maintenance.

Further, male participants described how they regarded their wife as taking an active role in ensuring sure that they were eating healthy:

Now she makes sure that she monitors all of my food intake, and that I have that cereal that tastes like lox in the morning, well, with fruit and nuts in it too, and yogurt. Health food for breakfast, and then a salad for lunch, and then a good meal for supper. Everything is more than adequately tended to regarding my diet.

I could only eat stuff that my wife specifically knew met the criteria for diabetic meals. Of course, she monitors what I drink too, so no more sweet tea, which I forgot to say a while ago. She cut off my sweet tea except that she observed me putting those little pink things in.

However, not all family influences were viewed as positive. One female participant expressed how her son influences her to choose less healthy food choices:

I watched what I eat. Because I’m here by myself during the day, or supposed to be, but my son was working away, and he’s home now, and he’s always saying, “Let’s go eat here,” and “What do you want to eat?” He thinks he’s taking care of me by feeding me, and then I think, “Well, what the heck? If he’s gonna pay for it, I’ll eat it anyway.

Barriers to Healthy Eating

Participants often alluded to the challenges of diet changes and/or portion control for the long-term, including not wanting to waste food, loss of motivation, cost, and community dinners. Two female participants expressed common reasons included not wanting to waste food or simply that it was tiring to keep a balanced diet.

When I do eat, like when I eat here, I don’t like to waste food. And I guess that’s another bad thing; we didn’t waste food growing up. We ate what was put in front of us or starved. I have – like I said, I have to decide what it is I really want. They can tell you I’ll go through the line and I’ll say don’t, don’t, don’t. Because I don’t want to waste food. So, I can only pick out one or two things that I really want and that’s what I concentrate on. It’s not always like a well-balanced diet.

I remember when I was trying to watch what I was eating, but then there would come times, and I guess a lot of people, you just didn’t care. You got tired of trying to eat the right things and do what was right. And you got tired of that, and therefore you didn’t care. You just let yourself go.

Affordability of healthier foods was also a barrier for some, as exemplified by two male participants:

What I meant is financially we can’t go. We can’t afford to go to the grocery store every other day, buy all that (healthy) stuff. What we buy is that stuff in the can. It’s got a lot of salt in it, and that’s bad for diabetes too because when you buy special food along, let’s say, triple, or a dollar, or a dollar and a quarter for peas, you can buy all that stuff, and you still contributing to your diabetes. Any way you look at it, we’re in a jam in the financial world.

There again, honest to God factor that needs to be considered is, again, money. What’s cheap? The cheapest things you can get are taters and gravy. Ironically, what’s least? We can’t afford soy, or stuff like that. Why not go ahead and get what you can afford? That’s something I think more attention needs to be provided to.

In the participating tribal community, members almost universally referred to “Indian dinners” as “traditional.” One female participant discussed the commonly served foods in the community as being incompatible to effective dietary management of T2DM: “Well, usually, they have the Indian bean bread, and fatback, and fried chicken, fried potatoes, fried everything. And that’s probably fried in grease instead of oil.” The paradox between the community-wide message to eat healthier and then communities simultaneously promoting “Indian dinners” was illustrated in the following statement from a male participant:

Mixed messages – we send out messages with our mouth but we don’t act out the messages with our body about trying to live healthy. Every time they have a so-called Indian dinner it’s fatback grease and bean bread and fried cabbage and fried potatoes in the fatback and all the things that our bodies used to tolerate but don’t no longer. So we have mixed messages….

Participants expressed their awareness about the dangers of eating these foods as expressed here in these two quotes: “They are always harping about eating the right things, and then they’ll have all these Indian dinners served for benefits, and there’s always the wrong type of food to eat.” “Here, we call it traditional food, bean bread, lye dumpling, mustard greens, fried chicken, fried potatoes..., all that stuff is good. It may be good, but it’s dangerous.”

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to better understand dietary beliefs and dietary self-management of older American Indians with T2DM. This study adds to the limited research generated understandings of the experiences of dietary management in this population. The analyses revealed four emergent themes, including: 1) diet changes, 2) portion control, 3) healthcare professional and family influence, and 4) barriers to healthy eating.

Study participants shared dietary practices that they used to manage their T2DM. Diet changes included both replacing unhealthy with healthier food choices and cooking them in ways believed to be healthier. These findings reflect similar results from other studies with American Indians.7,8 In regard to portion control, participants also discussed strategies for limiting the daily amount of food they eat, which is similar to portion control beliefs among the Lakota Indians.7 The aforementioned dietary strategies coincide with nutrition therapy recommendations for those with T2DMs.5

Study participants also expressed how information and positive support from healthcare professionals and family members were instrumental in their dietary self-management efforts. Indeed, family and other social supports’ effect on successful T2DM self-management has been demonstrated in an earlier study in this tribal community27 and other American Indian and Alaska Native communities.30,31 Despite this support, perspectives shared from participants indicate that personal beliefs (e.g., distaste for wasting food) and weariness of maintaining a healthy diet continue to thwart their ability to maintain a healthy diet.

In this study, barriers to adopting and maintaining a healthy diet included not wanting to waste food, loss of motivation, cost, and community dinners. Cost and motivation have also been found as significant barriers among American Indian men in Oklahoma.9 Cost of healthy foods appears to reflect the social and environmental circumstances in other American Indian and Alaska Native communities.30 “Food deserts,” areas with few or no affordable healthy food choices, are associated with higher T2DM prevalence among American Indians.31 American Indian adults who report food insecurity, the inability to access a sufficient quantity of affordable nutritious food, also report experiencing more barriers to accessing healthy foods.32 Growing concerns of these issues has fueled the “First Foods” movement in many Native communities.33 Some study participants viewed the promotion of “Indian dinners” at community events and fundraisers as divergent to messages from diabetes educators about healthier eating habits. However, it is important to clarify that these Indian dinners are not traditional in the sense that they represent what has been called “First Foods” or the foods typically consumed in the community prior to colonialization.34

This study has some limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, it is possible that perspectives of those who chose not to participate in the study substantially differ from those who did participate. Second, only one-on-one interviews were conducted. It is possible that more perspectives would have been shared in focus groups that would not have emerged from individual interviews. Last, while member-checking is a useful strategy in qualitative research to verify the transferability of findings, it was not conducted for this study. To help compensate for the lack of member-checking, the investigative team verified study findings with the CAB.

Implications for Research and Practice

These findings point to several important directions for future research. The Special Diabetes Program for Indians Diabetes Prevention demonstrated that the Diabetes Prevention Program can be effectively translated into American Indian and Alaska Native communities.35 Yet, given the diversity of infrastructure and resources across tribal communities, future studies are warranted to examine the program’s ability to positively impact dietary management and sustainability in specific tribal communities. Relatedly, community-based participatory research approaches are essential for the successful adoption and implementation of these programs to Native communities in ways that are culturally appropriate. As such, it is recommended that subsequent studies take an asset approach. For instance, a deeper and more nuanced assessment of how the social support network can be better leveraged to facilitate American Indians adhering to a diet supporting healthy T2DM management may hold promise for the augmentation of existing or the development of new community-based efforts. Further, an examination of persons with T2DM who maintained a healthy diet to identify the factors that supported their practices would yield valuable program planning and development information. Lastly, the Special Diabetes Program for American Indians found that older participants selected healthy foods more frequently than younger participants. Further study to assess these age differences in food choices is warranted as it may generate ideas for interventional efforts that include a multi-generational element.

To improve dietary practices in American Indian communities, it is essential to understand the values, beliefs, and barriers that can impact effective T2DM management.36 While findings from this study demonstrated that older American Indians understand the importance of incorporating healthier foods and cooking methods and monitoring the amount of caloric intake in managing their T2DM, they face several barriers, such as cost and unhealthy foods made available to them. Yet, as this study shows, healthcare professionals and family members can have a powerful impact on both adoption and adherence of healthy diets with this population. Clinicians and diabetes educators may want to consider the barriers to dietary adoption and adherence and determine the level of intervention needed to overcome those barriers and thus prevent the onset of T2DM complications for their patients.37 Another approach would be to implement changes in tribal community food environments.38 For example, local food stores could be engaged to increase and promote healthier food options. Similarly, developing and maintaining community gardens could increase access to healthier fresh produce.39 Given the continued higher prevalence of T2DM and negative health outcomes among American Indians,1,3,4 more diet-based interventional approaches both at the community (macro) level and the individual (micro) levels are needed.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Indian Health Service and the National Institutes of Health through the Native American Research Centers for Health [U261IHS0078].

Footnotes

Author Disclosure

None of the authors have a conflict of interest in regards to the content displayed in this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Mark Schure, Montana State University

R. Turner Goins, Western Carolina University, College of Health and Human Sciences

Jacqueline Jones, University of Colorado

Blythe Winchester, Cherokee Indian Hospital Authority.

Vickie Bradley, Public Health and Human Services, Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion;2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Connell JM, Wilson C, Manson SM, Acton KJ. The costs of treating American Indian adults with diabetes within the Indian Health Service. Am J Public Healh. 2012;102(2):301–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Indian Health Service. Diabetes in American Indians and Alaska Natives: Facts at a glance. Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services;2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2011: With Special Feature on Socioeconomic Status and Health. In. Hyattsville, MD2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Diabetes Association. 4. Lifestyle management: Standards of medical care in diabetes—2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(Supplement 1):S38–S50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sami W, Ansari T, Butt NS, Ab Hamid MR. Effect of diet on type 2 diabetes mellitus: A review. Int J Health Sci. 2017;11(2):65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harnack L, Story M, Rock BH, Neumark-Sztainer D, Jeffery R, French S. Nutrition beliefs and weight loss practices of Lakota Indian adults. J Nutr Educ. 1999;31(1):10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sherwood NE, Harnack L, Story M. Weight-loss practices, nutrition beliefs, and weight-loss program preferences of urban American Indian women. J Ame Diet Assoc. 2000;100(4):442–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cavanaugh CL, Taylor CA, Keim KS, Clutter JE, Geraghty ME. Cultural perceptions of health and diabetes among Native American men. J Health Care Poor U. 2008;19(4):1029–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goins RT, Jones J, Schure M, Winchester B, Bradley V Type 2 diabetees management among older American Indians: Beliefs, attitudes, and practices. Ethnic Health. 2018; 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and its Burden in the United States, 2014. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Departement of Health and Human Services;2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Maas LD. Intergenerational analysis of dietary practices and health perceptions of Hispanic women and their adult daughters. J Transcult Nurs. 1999;10(3):213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashida S, Goodman M, Pandya C, Koehly LM, Lachance C, Stafford J, Kaphingst KA. Age differences in genetic knowledge, health literacy and causal beliefs for health conditions. Public Health Genomi. 2011;14:307–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teufel-Shone NI, Jiang L, Beals J, Henderson WG, Zhang L, Acton KJ, Roubideaux, Manson SM. Demographic characteristics and food choices of participants in the Special Diabetes Program for American Indians Diabetes Prevention Demonstration Project. Ethnic Health. 2015;20(4):327–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H. An aging nation: The older population in the United States. 2014.

- 16.Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Tribal Health Improvement Plan: 2015–2017. Cherokee, NC2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berger PL, Luckmann T The Social Construction of Reality. New York: Penguin; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. Washington, DC: Sage; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleinman A, Eisenberg L, Good B Cultural, illnes, and care: Clincial lessons for anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88(2):251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goins RT, Garroutte EM, Leading Fox S, Geiger SD, Manson SM. Theory and practice in participatory research: Lessons from the Native Elder Care Study. Gerontol. 2011;51(3):285–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shulman LS, Carey NB. Psychology and the limitations of individual rationality: Implications for the study of reasoning and civility. Rev Educ Res. 1984;54(4):501–524. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandelowski M Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krippendorff K Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shenton AK. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Educ Inform. 2004;22(2):63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goins RT, Noonan C, Gonzales K, Winchester B, Bradley VL. Association of depressive symptomology and psychological trauma with diabetes control among older American Indian women: Does social support matter? J Diabetes Complicat. 2017;31(4):669–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shaw JL, Brown J, Khan B, Mau MK, Dillard D. Resources, roadblocks and turning points: a qualitative study of American Indian/Alaska Native adults with type 2 diabetes. J Commun Health. 2013;38(1):86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epple C, Wright AL, Joish VN, Bauer M. The role of active family nutritional support in Navajos’ type 2 diabetes metabolic control. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(10):2829–2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Connell M, Buchwald DS, Duncan GE. Food access and cost in American Indian communities in Washington State. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(9):1375–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jernigan VBB, Wetherill MS, Hearod J, et al. Food insecurity and chronic diseases among American Indians in rural Oklahoma: The THRIVE study. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(3):441–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bauer KW, Widome R, Himes JH, et al. High food insecurity and its correlates among families living on a rural American Indian reservation. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1346–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dwyer E Farm to Cafeteria Initiatives: Connections with the tribal food sovereignty movement. National Farm to School Network;2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cozzo DN. The effect of traditional dietary practices on contemporary diseases among the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians In: Lefler L, ed. Under the Rattlesnake: Cherokee Health and Resiliency. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press; 2009:79–101. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang L, Manson SM, Beals J, Henderson WG, Huang H, Acton KJ, Roubideaux Y. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program into American Indian and Alaska Native communities. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2027–2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American Association of Diabetes Educators. Cultural considerations in diabetes education: AADE practice synopsis. July 28, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Powers MA, Bardlsley JB, Cypress M, et al. Diabetes self-management education and support in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educator. 2017;43(1):40–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gittelsohn J, Rowan M. Preventing diabetes and obesity in American Indian communities: The potential of environmental interventions. Am J Clin Nutri. 2011;93(5):1179S–1183S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lombard KA, Beresford SA, Ornelas IJ, et al. Healthy gardens/healthy lives: Navajo perceptions of growing food locally to prevent diabetes and cancer. Health Promot Practice. 2014;15(2):223–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]