Abstract

Purpose:

To evaluate and compare the retinal microvasculature in the superficial capillary plexus (SCP) in persons with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and cognitively intact controls using optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA). Various OCT parameters were also compared.

Design:

Cross-sectional study.

Participants:

70 eyes from 39 AD subjects, 72 eyes from 37 MCI subjects, and 254 eyes from 133 control subjects were enrolled.

Methods:

Subjects were imaged using the Zeiss Cirrus HD-5000 with AngioPlex. All subjects underwent cognitive evaluation with Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE).

Main Outcome Measures:

The vessel density (VD) and perfusion density (PD) in the SCP within the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) 6mm circle, 3mm circle, and 3mm ring were compared between groups. The foveal avascular zone (FAZ) area, central subfield thickness (CST), macular ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer (GC-IPL) thickness, and peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness were also compared.

Results:

AD subjects had a significantly decreased SCP VD and PD in the 3mm ring (p=0.001 and 0.002 respectively) and 3mm circle (p=0.003 and 0.004 respectively) as well as VD in the 6mm circle (p=0.047) when compared to MCI and a significantly decreased SCP VD and PD in the 3mm ring (p=0.008 and 0.004 respectively) and 3mm circle (p=0.015 and 0.009 respectively) as well as PD in the 6mm circle (p=0.033) when compared to cognitively intact controls. However, there was no difference in SCP VD or PD between MCI and controls (p>0.05). The FAZ area and CST did not significantly differ between groups (p>0.05). AD subjects had significantly decreased GC-IPL thickness over the inferior (p=0.032) and inferonasal (p=0.025) sectors compared to MCI subjects and significantly decreased GC-IPL thickness over the whole (p=0.012), superonasal (p=0.041), inferior (p=0.004), and inferonasal (p=0.006) sectors when compared to controls. MCI subjects had significantly decreased temporal RNFL thickness (p=0.04) compared to controls.

Conclusions:

AD subjects had significantly reduced macular VD, PD, and GC-IPL thickness compared to MCI and control subjects. Changes in the retinal microvasculature may mirror small vessel cerebrovascular changes in AD. These parameters may serve as surrogate non-invasive biomarkers in the diagnosis of AD.

Précis

Alzheimer’s disease subjects had significantly decreased vessel density and perfusion density using OCT angiography, and ganglion cell layer-inner plexiform layer thickness using OCT compared to mild cognitive impairment and cognitively intact control subjects.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common subtype of dementia (60–80%) with an estimated 5.5 million individuals affected in the United States alone.1 The health and societal costs associated with AD are expected to increase with a projected 13.8 million individuals affected by 2050.1 While AD is characterized by memory deficits, aphasia, apraxia, and agnosia,2 mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is considered a transitional stage between normal aging and dementia with cognitive decline that does not notably interfere with activities of daily life.3 An estimated 32% of MCI patients will progress to develop AD within 5 years’ follow-up.4 Due to the increasing prevalence of AD and paucity of effective treatment options, identification of a biomarker for potentially earlier diagnosis and enrollment into interventional clinical trials has become a priority. Current diagnostic modalities for AD and MCI are limited by cost (e.g. magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography [PET]), invasiveness (e.g. cerebrospinal fluid), suboptimal specificity and sensitivity (e.g. genetic markers, serum amyloid), length of evaluation, access to specialists, and neuropsychological evaluation.5 Faster, more accessible, less invasive diagnostic techniques are a large unmet need for efficient screening of those at risk.

The neuropathology of Alzheimer’s consists of the deposition of β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, both of which lead to inflammation and neurodegeneration.6 Cerebral microvascular changes are currently inaccessible to existing in vivo imaging technologies. In contrast, the retinal microvascular network can be directly imaged and may provide a unique “window” to study parallel cerebral microvascular pathology7 since the retinal and cerebral microvasculature share similar embryological origins as well as anatomical and physiological properties.8 Changes in the brain may also be detectable in the retina in individuals genetically predisposed to or with clinical symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease.9 Optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging has been used to detect neurodegenerative changes occurring in the ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer (GC-IPL) thickness and retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness of AD and MCI patients.10–12 La Morgia and colleagues13 observed decreased RNFL thickness in AD subjects in vivo through OCT and significant loss of melanopsin retinal ganglion cells in postmortem AD retina specimens.

In addition to neurodegenerative changes, the contribution of vascular remodeling to MCI and AD is increasingly recognized.7,14,15 Postmortem studies of the cerebral microvasculature in AD have shown impairment of the blood-brain barrier and decreased capillary density, length, and mean diameters in comparison to controls.16,17 A study utilizing fundus photography showed abnormal retinal vascular parameters in AD subjects, which included vascular attenuation, increasing standard deviation of vessel widths, reduced complexity of the branching pattern, reduced optimality of the branching pattern, and less tortuous venules.18 OCT angiography (OCTA) may permit detection of reduction in capillary vessel and perfusion density before they are visible on retinal photographs.19 Two previous OCTA studies have reported decreased retinal vascular density in AD.20,21

We sought to identify retinal microvasculature biomarkers using OCTA that may potentially aid in the earlier diagnosis of AD by comparing individuals with AD and MCI to cognitively intact community controls.

Methods

Participants and Protocol

This cross-sectional study (Clinicaltrials.gov NCT03233646) was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Research at the Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, North Carolina and followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their designated medical power of attorney before enrollment.

Eligible AD and MCI subjects aged ≥50 years were enrolled from the Duke Memory Disorders Clinic. AD and MCI subjects were initially evaluated and clinically diagnosed by an experienced neurologist (J.R.B.) based on the diagnostic guidelines and recommendations of the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association.22,23 Clinical history, cognitive testing, and neuroimaging were reviewed for diagnostic accuracy by an experienced neurologist (J.R.B.) with a specialization in memory disorders. Subjects did not undergo PET imaging or lumbar puncture for assessment of biomarker status. Community control subjects were healthy volunteers aged ≥50 years without subjective memory complaints who were either spouses or attendants to patients at the Duke Memory Disorders Clinic or who were from the Bryan Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) registry of control subjects. The ADRC maintains a registry of cognitively normal community control subjects based on extensive cognitive tests, which include Montreal Cognitive Assessment, Trail Making Test, and Delayed Recall from the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) Word-List.10 Exclusion criteria for all study participants included a history of non-AD associated dementia, diabetes mellitus, uncontrolled hypertension, demyelinating disorders, glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration (AMD), other vitreoretinal pathology that could interfere with OCT and OCTA analysis, and corrected Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) visual acuity worse than 20/40 on the day of image acquisition. All subjects underwent a Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) to evaluate cognitive function on the same day as image acquisition. Years of education were collected from each patient and were calculated from the first grade onwards.

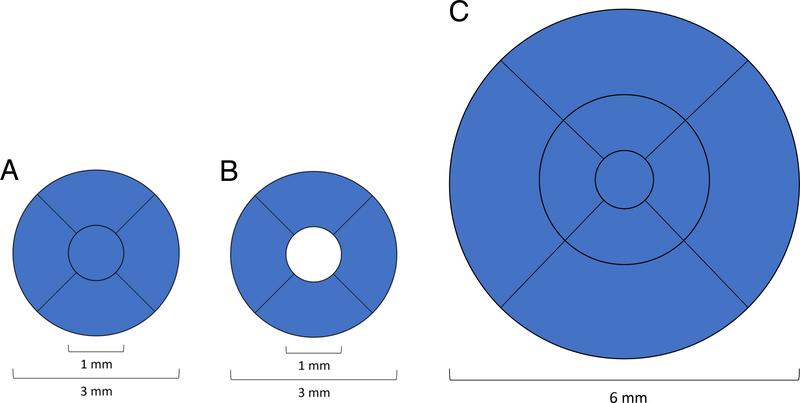

Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Image Acquisition

All subjects were imaged with the Zeiss Cirrus HD-5000 Spectral-Domain OCT with AngioPlex OCT Angiography (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA) that has a scan rate of 68,000 A-scans per second, central wavelength of 840 nm, motion tracking to reduce motion artifact, and uses an optical microangiography (OMAG) algorithm for analysis.19 Both 3×3mm and 6×6mm images centered on the fovea were acquired. OCTA images that were of poor scan quality (less than 7/10 signal strength) due to low resolution or poor saturation, and those that exhibited motion artifacts due to poor cooperation were excluded. The inner boundary of the superficial capillary plexus (SCP) slab was defined as the internal limiting membrane and outer boundary was the inner plexiform layer which was calculated as 70% of the distance from the internal limiting membrane to the estimated boundary of the outer plexiform layer, which in turn was determined as being 110 μm above the retinal pigment epithelium boundary as automatically detected by the software (Carl Zeiss Meditec Version 10.0.0.14618). The software quantified the average vessel density (VD) and perfusion density (PD) using a grid overlay according to the standard ETDRS subfields. VD was defined as the total length of perfused retinal microvasculature per unit area in the region of measurement, whereas PD was defined as the total area of perfused retinal microvasculature per unit area in a region of measurement. VD and PD were calculated for the 3mm circle and 3mm ring for 3×3mm images and over the entire ETDRS 6mm circle for 6×6mm scans (Figure 1). The foveal avascular zone (FAZ) boundaries were automatically calculated by the software; values with inaccurate boundaries identified on manual review were excluded.

Figure 1.

Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) grid regions used for (A) 3mm circle, (B) 3mm ring, and (C) 6mm circle regions. Vessel density and perfusion density were averaged over the highlighted blue area for each respective region.

Optical Coherence Tomography Image Acquisition

For all subjects, the same Cirrus HD-OCT 5000 (Carl Zeiss Meditec) was utilized to acquire a 512×128 macular cube and 200×200 optic disc cube. OCT images with poor quality (less than 7/10) or motion artifacts were excluded. OCT software (Carl Zeiss Meditec) automatically quantified CST as the thickness between the inner limiting membrane and retinal pigment epithelium at the fovea from the macular cube. Average GC-IPL thickness was automatically quantified over the 14.13 mm2 elliptical annulus area centered on the fovea and over 6 sectors of the annulus, including the superotemporal, superior, superonasal, inferotemporal, inferior, and inferonasal sectors. Average RNFL thickness was automatically quantified over a 3.46 mm diameter circle centered on the optic disc and over 4 sectors of the circle, including the superior, temporal, nasal, and inferior sectors.

Statistical Analysis

Multivariate statistical analysis was completed in STATA 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Baseline demographic variables of study subjects were compared overall across groups using Chi-square test for categorical variables and ANOVA or K-wallis test for continuous variables. Scores on the MMSE were also compared between groups using a multivariate tobit regression analysis that controlled for years of education. Multivariate generalized estimating equations (GEE) for each of the OCT and OCTA imaging parameters with adjustment for age and gender were used to compare AD, MCI and control subjects. The logMAR visual acuity was also compared between groups using GEE models. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Ordinary least squares regression analysis and Spearman’s correlation were performed to explore the relationship between each of the averaged VD, PD, or FAZ area SCP parameters in the 6×6mm or 3×3mm circles with MMSE among all subjects. The relationships between average RNFL thickness, average GC-IPL thickness, and CST with MMSE were also explored with Spearman’s correlation among all subjects.

Results

A total of 90 eyes from 52 AD subjects, 79 eyes from 41 MCI subjects, and 269 eyes from 142 healthy control subjects were enrolled and imaged. A total of 20 eyes from 13 AD subjects, 7 eyes from 4 MCI subjects, and 15 eyes from 11 control subjects were excluded from the analysis due to poor OCTA image quality or motion artifact. Of these 42 eyes excluded, 22 were due to poor scan quality and 20 due to motion artifact. Some AD patients were easily fatigued and were more prone to fixation errors; as a result, 22.2% of imaged AD eyes were excluded from analysis due to poor scan quality (less than 7/10) or motion artifacts. A total of 70 eyes from 39 AD subjects, 72 eyes from 37 MCI subjects, and 254 eyes from 133 healthy control subjects were analyzed. The average corrected ETDRS visual acuity in AD (0.20 ± 0.10) was not significantly different than that of MCI (0.16 ± 0.10; p=0.11), but was lower that of control eyes (0.11 ± 0.10; p<0.001), and the difference between MCI and controls (p<0.001) was also significant.

There was a significant difference in age but no significant difference in gender among the groups (Table 1). The average age of the AD group (72.8 ± 7.7) was older than the MCI group (71.1 ± 7.6) and control group (69.2 ± 7.8). The MMSE score was lower in both the AD (p<0.001) and MCI (p<0.001) groups compared to the control group, even after controlling for years of education (Table 1). In addition, the AD group had a lower MMSE score compared to the MCI group (p=0.033) and the MCI group had a lower MMSE than the controls (p<0.001), after adjusting for years of education.

Table 1.

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics.

| Parameter | AD (n = 39) | MCI (n = 37) | Control (n = 133) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (mean ± standard deviation) | 72.8 ± 7.7 | 71.1 ± 7.6 | 69.2 ± 7.8 | 0.03a |

| Female gender % (n) | 66.6% (n=26/39) | 54.1% (n=20/37) | 72.9% (n=97/133) | 0.09b |

| Years of education (mean ± standard deviation) | 15.6 ± 2.4 | 15.1 ± 1.9 | 17.2 ± 2.3 | <0.001c |

| MMSE score (mean ± standard deviation) | 20.1 ± 5.9 | 22.6 ± 4.7 | 29.2 ± 1.1 | <0.001c, d |

ANOVA for age

Chi-square test for gender, and

K-Wallis test for years of education and MMSE.

p-value statistically significant after controlling for years of education in a tobit multivariate regression model.

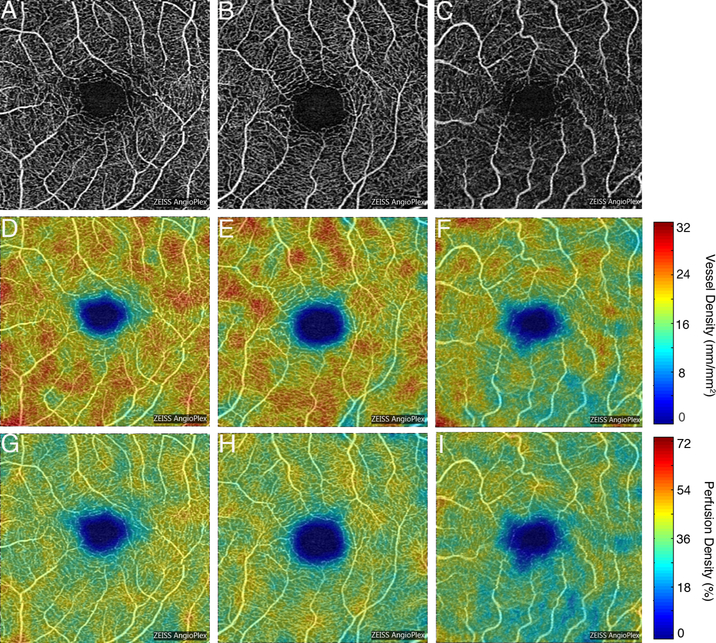

Comparing AD to MCI, the AD group had significantly decreased 3mm circle VD (p=0.003) and 3mm ring VD (p=0.001) as well as decreased 3mm circle PD (p=0.004) and 3mm ring PD (p=0.002) compared to the MCI group (Figure 2). The AD group also had significantly reduced 6mm circle VD (p=0.047) compared to the MCI group (Table 2). The 6mm circle PD (p=0.053) was not significantly different between the AD and MCI groups. The AD group had significantly decreased inferior GC-IPL (p=0.032) and inferonasal GC-IPL (p=0.025) thicknesses compared to the MCI group (Supplemental Table 1). There were no significant differences between AD and MCI subjects in RNFL thickness (p>0.05).

Figure 2.

Representative optical coherence tomography angiography 3×3mm images of the superficial capillary plexus (SCP) of the left eye from a community control subject (A), mild cognitive impairment (MCI) subject (B), and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) subject (C). Corresponding quantitative color maps (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA) of vessel density (D-F) and perfusion density (G-I) of the SCP, with the scale on the right, show decreased vessel density and perfusion density in the subject with AD (F, I) compared to the control subject (D, G) and MCI subject (E, H).

Table 2.

Comparison of OCT angiography parameters for 3×3mm circle and ring regions and 6×6mm circle region among subjects with Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, and cognitively intact community controls by generalized estimating equations multivariate analysis with adjustment for age and gender.

| OCTA Parameter | AD | MCI | Controls | AD vs. Controls: Beta coefficient (95% CI), p-value | AD vs. MCI: Beta coefficient (95% CI), p-value | MCI vs. Controls: Beta coefficient (95% CI), p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3mm circle VD (/mm) | 19.0±2.3 | 20.3±1.5 | 20.2±1.6 | −0.87 (−1.57, −0.17) p=0.015 | −1.18 (−1.96, −0.40), p=0.003 | 0.27 (−0.15, 0.70), p=0.20 |

| 3mm circle PD | 0.347±0.037 | 0.366±0.024 | 0.365±0.026 | −0.015 (−0.026, 0.004), p=0.009 | −0.018 (−0.03, 0.006), p=0.004 | 0.003 (−0.004, 0.009), p=0.44 |

| 3mm ring VD (/mm) | 20.1±2.3 | 21.4 ±1.5 | 21.3±1.5 | −0.93 (−1.62, 0.24), p=0.008 | −1.26 (−2.03, −0.48), p=0.001 | 0.30 (−0.12, 0.272), p=0.17 |

| 3mm ring PD | 0.366±0.036 | 0.386 ±0.024 | 0.386±0.025 | −0.016 (−0.026, 0.005) p=0.004 | −0.019 (−0.031, 0.007), p=0.002 | 0.003 (−0.004, 0.009), p=0.38 |

| 6mm circle VD (/mm) | 17.4±1.5 | 17.9 ±1.0 | 17.9±1.1 | −0.42 (−0.84, 0.006), p=0.053 | −0.47 (−0.94, 0.006), p=0.047 | 0.11 (−0.18, 0.39), p=0.46 |

| 6mm circle PD | 0.427±0.041 | 0.441±0.025 | 0.440±0.026 | −0.012 (−0.023, 0.001), p=0.033 | −0.011 (−.023,0.0001), p=0.053 | −0.0008 (−0.006, 0.007), p=0.81 |

| FAZ area (mm2) | 0.25±0.13 | 0.24±0.10 | 0.25±0.11 | −0.002 (−0.045, 0.04), p=0.91 | 0.003 (−0.045, 0.05), p=0.92 | −0.001 (−0.037, 0.034), p=0.94 |

OCTA = optical coherence tomography angiography; VD = vessel density; PD = perfusion density; FAZ = foveal avascular zone

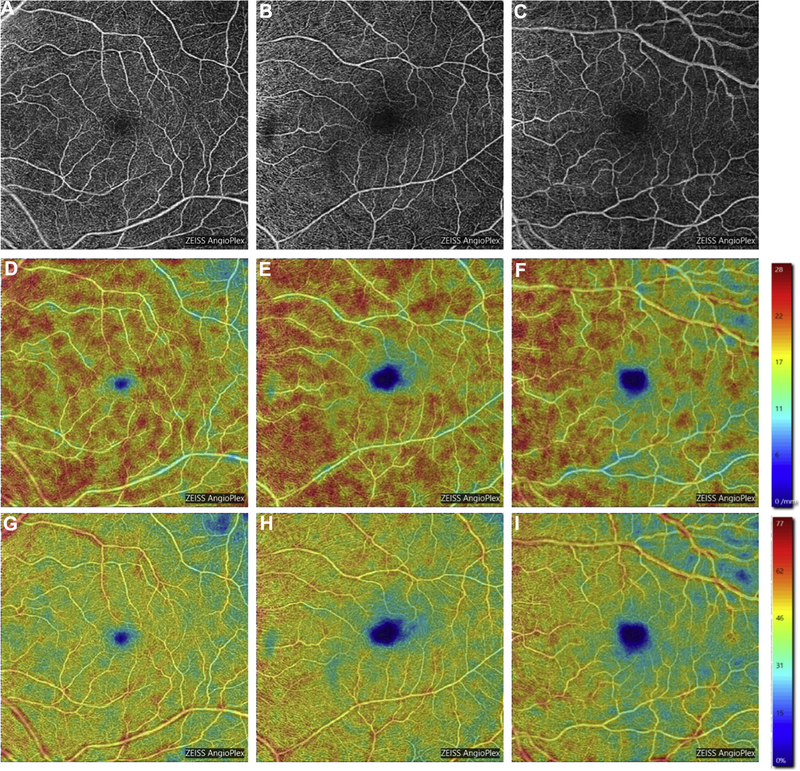

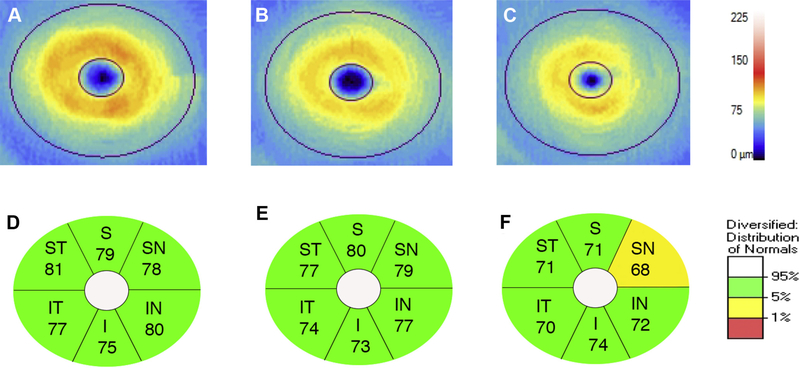

Comparing AD to controls, the AD group had significantly decreased 3mm circle VD (p=0.015), 3mm circle PD (p=0.009), 3mm ring VD (p=0.008), and 3mm ring PD (p=0.004) compared to the control group (Figure 2). The AD group also had significantly reduced 6mm circle PD (p=0.033) compared to the control group (Table 2). The 6mm circle VD (p=0.053) was not significantly different between the AD and control groups (Figure 3). The AD group had significantly reduced GC-IPL thickness over the whole (p=0.012), superonasal (p=0.041), inferior (p=0.004), and inferonasal (p=0.006) sectors compared to the control group (Figure 4). There were no significant differences between AD and control subjects in RNFL thickness (p>0.05).

Figure 3.

Representative optical coherence tomography angiography 6×6mm images of the superficial capillary plexus (SCP) of the left eye from a community control subject (A), mild cognitive impairment (MCI) subject (B), and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) subject (C). Corresponding quantitative color maps (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA) of vessel density (D-F) and perfusion density (G-I) of the SCP, with the scale on the right, show decreased vessel density and perfusion density in the subject with AD (F, I) compared to the control subject (D, G) and MCI subject (E, H).

Figure 4.

Ganglion cell analysis (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA) of representative optical coherence tomography images of the macula of the left eye in a control subject (A), MCI subject (B), and AD subject (C). Corresponding GC-IPL thickness for each elliptical annular region shows diffuse thinning in the AD subject (F) compared to the control (D) and MCI subjects (E). S, superior; ST, supero-temporal; SN, supero-nasal; I, inferior; IT, infero-temporal; IN, inferonasal.

Comparing MCI to controls, there were no significant differences between the MCI and control groups for VD and PD in the 3mm circle, 3mm ring, nor in the 6mm circle (all p>0.05). Temporal RNFL thickness was significantly decreased in the MCI subjects compared to the control subjects (p=0.04). There were no significant differences between MCI and control subjects in GC-IPL thickness (p>0.05).

FAZ area and CST were not significantly different between any of the groups (all p>0.05) (Table 2 and Supplemental Table 1).

Correlations between OCTA and OCT parameters with MMSE were analyzed through Spearman’s correlation coefficients. For 3×3mm OCTA parameters, 3mm circle VD ( =0.153, p=0.003), 3mm ring VD ( =0.168, p=0.001), 3mm circle PD ( =0.146, p=0.004), and 3mm ring PD ( =0.160, p=0.002) were significantly correlated with MMSE among all subjects (all p<0.005) (Supplemental Table 2). No significant correlations were found between 3×3mm FAZ area or 6×6mm VD or PD parameters with MMSE (all p>0.05). For OCT parameters, average RNFL thickness ( =0.132, p=0.009) and average GC-IPL thickness ( =0.234, p<0.001) were significantly correlated with MMSE (Supplemental Table 2). CST was not significantly correlated with MMSE (p>0.05).

Discussion

In this large cross-sectional study of OCTA findings in AD and MCI, we observed significantly decreased VD and PD in both the 3×3 and 6×6 mm scans using ETDRS subfields in AD subjects when compared to both MCI and control subjects. These differences suggest that VD and PD may be imaging biomarkers useful in screening for AD in symptomatic individuals and may be able to distinguish between MCI and AD. This is the first study to evaluate both VD and PD of the SCP in AD, MCI, and control subjects.

The mechanism underlying reduced retinal vessel density in AD is unknown but decreased angiogenesis from sequestration of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in Aβ plaques and competitive binding of Aβ to VEGF receptor 2 has been proposed.17 Koronyo and colleagues6 identified Aβ plaques in the retina of 8 postmortem AD subjects and 5 suspected early-stage cases. Furthermore, Koronyo and colleagues6 detected Aβ plaques in the retina of APPSWE/PS1ΔE9 transgenic mice earlier than plaques in the brain that accumulated with disease progression. Aβ deposition around vascular walls disrupts the basement membrane of small vessels, causing endothelial damage, and reducing the vascular lumen.17 In a follow-up histological study by Koronyo and colleagues24 of 37 definite AD and control subjects, Aβ plaques in the retina were associated with blood vessels and were observed inside blood vessels, perivascular, and along blood vessel walls. The study also utilized systemic administration of curcumin in 16 living human subjects to show marked increase in fluorescence of retinal Aβ deposits at 10 days through a scanning laser ophthalmoscope.24 Although curcumin allows for direct visualization of Aβ plaques, the systemic administration of curcumin is invasive and requires significant time for optimal fluorescence of plaques, which make it difficult to adapt to clinical practice. The association of Aβ plaques to retinal blood vessels in histological studies strengthens the case for the use of OCTA to detect microvascular abnormalities in AD pathology.

Our findings support a previous, smaller study that reported decreased vascular density of the SCP in 26 eyes of AD subjects when compared to 26 eyes of control subjects using OCTA, with exclusion of subjects with glaucoma, diabetes, and macular degeneration.20 They utilized a 6×6mm OCTA scan (RTVue XR100–2, Optovue, Fremont, CA) and reported differences in the vascular density of foveal, parafoveal, and whole regions. In addition to decreased PD in the 3mm ring, 3mm circle, and 6mm circle between the AD group and control group, our study observed significantly decreased VD in eyes of subjects with AD in the 3mm ring and 3mm circle compared to controls. Our study also had decreased 3mm ring, 3mm circle, and 6mm circle VD in AD patients compared to MCI participants. The VD measurement quantifies density by considering the total length of the vessels and does not account for vessel diameter. Both large vessels and small capillaries contribute equally to VD. Therefore, VD may be a more sensitive measure for perfusion changes at the capillary level when assessing the retinal microvasculature in AD.25 Another smaller OCTA study by Jiang and colleagues21 found reduced fractal dimension in the SCP and DCP of 12 AD subjects and in one quadrant of the DCP in 19 MCI subjects compared to 21 controls using the Zeiss Angioplex OCTA. However, their study did not exclude glaucoma or controlled type 2 diabetics, which may affect OCTA parameters.25,26 In addition, fractal dimension is a measure of global branching complexity of the OCTA image, which may not reflect early microvascular changes.27 We did not evaluate the middle or deep capillary plexus in this study and our analysis is limited to the SCP since it is easier to segment and provides fewer artifact such as projection artifact and issues with low resolution, we are evaluating the middle and deep plexus.

Our OCTA findings also support previous studies that evaluated the retinal vasculature using fundus photographs wherein AD patients had narrower venular caliber, decreased arteriolar and venular fractal dimensions, and increased arteriolar and venular tortuosity.7,14 Williams and colleagues observed lower venular fractal dimension and decreased arteriolar tortuosity in the largest case-control study of AD using fundus photography.28 Frost and colleagues18 reported differences in 13 retinal vascular parameters in 25 AD subjects compared to 123 healthy controls through analysis of fundus photographs. Key vascular parameters found to be different included central retinal artery and vein caliber, standard deviation of vessel width, arteriole-to-venule ratio, fractal dimension of venular network, and asymmetry factor of the venule network. Retinopathy on fundus photography was associated with cognitive decline.29 However, visible retinopathy is a relatively late indicator of target organ damage and probably reflects advanced stages of structural microvascular damage.30 Quantitative metrics of VD and PD of the SCP using OCTA may detect areas of vascular loss that are not yet visible on fundus photographs.31

There were no significant differences observed for VD or PD in the 3mm ring, 3mm circle, and 6mm circle between the MCI and control groups in our study. Feke and colleagues,14 however, observed retinal blood flow differences between AD and MCI, AD and controls, and MCI and controls using laser Doppler on the largest temporal vein one disc diameter away from the optic disc margin. MCI subjects were found to have a 19.4% decrease in retinal blood flow compared to controls, while AD subjects had a 39% decrease relative to controls. Venous blood column diameter was not different in MCI versus control groups, but it was decreased in AD subjects.14 The lack of difference between MCI and controls in our study may be due, in part, to the location of the blood vessels measured and the different metrics being analyzed. The laser Doppler measurements were taken near the optic disc, while our measurements of the SCP were centered at the macula. The radial peripapillary capillary (RPC) plexus is distinguished from the SCP by its concentration in the inferotemporal and superotemporal peripapillary areas and absence in the fovea.32 RPCs have fewer anastomoses when compared to the SCP, which may make them more susceptible to vascular dysfunction.32 We are currently evaluating whether peripapillary OCTA measurements may be more sensitive in detecting changes in AD and MCI subjects. Furthermore, VD and PD are assessing the retinal microvascular structure, which may not be mediated by the same mechanism of decreased blood flow. Structural biomarkers such as VD, PD, and venous blood column diameter may change later in the pathological processes of AD.

The FAZ area was not significantly different among the groups in our study. We manually reviewed all FAZ boundaries constructed by the software to ensure anatomical accuracy. Two studies have previously evaluated the relationship between AD pathology and FAZ area. A small study by Bulut and colleagues20 with 26 AD and 26 control subjects showed a larger FAZ area in the AD group compared to the control group. Another small study by O’Bryhim and colleagues33 with 58 eyes from 30 cognitively healthy participants reported an enlarged FAZ area in the group positive for amyloid biomarkers (cerebrospinal fluid analysis and PET imaging) compared to the control group. Furthermore, significant variation in FAZ area in normal eyes has been reported in prior studies, which may be associated with gender, central retinal thickness, and retinal vessel density.34,35 In addition, enlargement in FAZ area may be due to confounding factors that were not controlled for and additional studies with larger sample sizes may be needed to confirm if the finding is related to AD pathology.

Although CST was slightly decreased in both AD and MCI relative to controls, this relationship did not reach statistical significance. Our results differ from previous studies that have found significantly decreased CST in AD.36–38 A systematic review and meta-analysis of 302 AD patients and 241 controls from seven OCT studies showed decreased macular thickness in AD, which was most prominent in the outer ring of the ETDRS grid.37 The decrease in macular thickness in the outer ring may reflect retinal nerve fiber layer loss more peripherally, while the central macula was the region with the least relative thinning compared to controls. Open-angle glaucoma is a risk factor for AD39, and the outer ring is the first region of thinning in early glaucoma patients.40,41 The rigor of adjustment for confounders such as glaucoma may potentially be a factor in the macular thinning observed in previous studies.

We found significantly decreased GC-IPL thickness in AD compared to MCI and controls. Our finding is supported by a systematic review and meta-analysis reporting decreased GC-IPL thickness in 201 AD subjects when compared to 311 control subjects.12 Morphometric analysis in postmortem AD eyes also revealed a 25% decrease in total number of ganglion cell layer neurons compared to controls in the central retina.42 Williams and colleagues43 reported that retinal ganglion cell (RGC) dendritic atrophy preceded cell loss in a mouse model of AD, which suggests that GC-IPL thickness may be a useful biomarker for early detection of AD. Thinning of the GC-IPL has been associated with lower gray matter volumes in the visual cortex and cerebellum, as well as lower white matter microstructure integrity on MRI.44 Thinning of GC-IPL is a retinal biomarker that may reflect neurodegenerative changes in the brain and improve screening of AD when combined with evaluation of the retinal microvasculature with OCTA.

Our study found a significantly decreased temporal peripapillary RNFL thickness in MCI subjects compared to controls, but no significant differences in peripapillary RNFL thickness between the AD group and the MCI or control groups. In a systematic review and meta-analysis, Chan and colleagues12 reported a significantly decreased peripapillary RNFL thickness of 1061 AD subjects compared to 1130 controls, as well as no significant difference in RNFL thickness between 198 MCI subjects and 1130 controls. The different result in our study may be attributed to the variability of case identification, exclusion criteria of confounding factors (glaucoma and retinal disease), OCT models, and segmentation algorithms in other studies.10,45 Because the macula contains approximately 50% of the total RGC population whose cell bodies are 10 to 20 times the diameter of their axons, macular GC-IPL thickness may be a more sensitive marker of AD-related neurodegeneration than RNFL thickness.11,46

There were no significant differences in VD, PD, FAZ area, CST, and GC-IPL thickness between MCI subjects and controls in our study. MCI is a complex, heterogeneous group that includes patients who may not progress to AD, revert back to being cognitively normal, or develop non-AD dementia.47 The MCI group in our study had a significantly lower MMSE than the control group, which supports the clinical diagnosis of MCI and associated decreased cognitive function. We carefully excluded other major etiologies of MCI, such as frontotemporal dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies, and vascular dementia, prior to enrollment. The role of Aβ plaques in MCI is still unanswered, with aged controls exhibiting a similar extent of Aβ deposition to MCI in postmortem brain tissue and brain PET imaging.48–50 Although our study was the largest OCTA study of AD and MCI to date, additional studies with larger sample sizes may be needed to detect differences in the MCI group, possibly with segregation into amnestic and non-amnestic groups, relative to controls with regard to OCTA and OCT parameters.

The strengths of this study include that it is the largest prospectively imaged cohort of AD and MCI individuals using OCTA to date with stringent adherence to scan quality. In addition, we had a robust control group with approximately a 4:1 control-to-case ratio. We also adjusted for age and gender during multivariate analysis and excluded possible confounding factors, such as diabetes, uncontrolled hypertension, glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration and other vitreoretinal diseases, through our enrollment criteria. Although the age was statistically different among the groups, there still relatively close in age with the mean difference between AD and controls being 3.6 years and between MCI and controls being 2.6 years.

Advanced AD patients are easily fatigued by imaging and are more prone to fixation errors; this led to 22.2% of the AD patients imaged in our study being excluded from analysis due to poor scan quality as compared to 8.9% of MCI and 5.6% of controls. OCTA may not be feasible, or perhaps even necessary, in subjects with advanced dementia and may be most useful for targeting patients with milder disease. Due to the cross-sectional design of the study, our study was limited by not being able to examine causal or temporal relationships between the retinal microvasculature in AD or MCI, nor were we able to assess progression. In addition, the utilization of brain amyloid PET scanning could produce a more homogenous group of MCI subjects in future work that may demonstrate a difference between MCI and control subjects.51

In conclusion, AD subjects had a significantly reduced macular VD and PD compared to MCI as well as control subjects, but there were no significant differences in either the FAZ or CST. Changes in the retinal microvasculature may mirror small vessel cerebrovascular changes in AD. These parameters may serve as surrogate non-invasive biomarkers for the diagnosis of AD. Future studies are needed to determine whether such tests will be able to detect progression of MCI to AD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported in part by funding from the National Institutes of Health P30EY005722 to Duke University, the 2018 Unrestricted Grant from Research to Prevent Blindness (Duke University), and the Karen L. Wrenn Alzheimer’s Disease Award. None of the funding agencies had any role in the design or conduct of this research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No conflicting relationship exists for any author.

Meeting Presentation: Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology, April 29-May 2, 2018, Honolulu, Hawaii; Duke Residents’ and Fellows’ Day, June 13–15, 2018, Durham, NC; American Academy of Ophthalmology, October 27–30, 2018, Chicago, Illinois

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the United States (20102050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology 2013;80:1778–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galton CJ, Patterson K, Xuereb JH, Hodges JR. Atypical and typical presentations of Alzheimer’s disease: a clinical, neuropsychological, neuroimaging and pathological study of 13 cases. Brain 2000;123:484–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gauthier S, Reisberg B, Zaudig M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment. Lancet 2006;367:1262–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward A, Tardiff S, Dye C, Arrighi HM. Rate of conversion from prodromal Alzheimer’s disease to Alzheimer’s dementia: a systematic review of the literature. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra 2013;3:320–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grossman I, Lutz MW, Crenshaw DG, et al. Alzheimer’s disease: diagnostics, prognostics and the road to prevention. EPMA J 2010;1:293–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koronyo-Hamaoui M, Koronyo Y, Ljubimov AV., et al. Identification of amyloid plaques in retinas from Alzheimer’s patients and noninvasive in vivo optical imaging of retinal plaques in a mouse model. Neuroimage 2011;54:S204–S217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheung CYL, Ong YT, Ikram MK, et al. Microvascular network alterations in the retina of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement 2014;10:135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patton N, Aslam T, MacGillivray T, et al. Retinal vascular image analysis as a potential screening tool for cerebrovascular disease: a rationale based on homology between cerebral and retinal microvasculatures. J Anat 2005;206:319–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz M, London A, Benhar I, Schwartz M. The retina as a window to the brain —from eye research to CNS disorders. Nat Rev Neurol 2012;20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lad EM, Mukherjee D, Stinnett SS, et al. Evaluation of inner retinal layers as biomarkers in mild cognitive impairment to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 2018;13:e0192646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yim C, Cheung-Lui, Ong YTL, et al. Retinal ganglion cell analysis using high-definition optical coherence tomography in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2015;45:45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan VTT, Sun Z, Tang S, et al. Spectral domain-optical coherence tomography measurements in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2018;doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.La Morgia C, Ross-Cisneros FN, Koronyo Y, et al. Melanopsin retinal ganglion cell loss in Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol 2016;79:90–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feke GT, Hyman BT, Stern RA, Pasquale LR. Retinal blood flow in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2015;1:144–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heringa SM, Bouvy WH, van den Berg E, et al. Associations between retinal microvascular changes and dementia, cognitive functioning, and brain imaging abnormalities: a systematic review. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013;33:983–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith EE, Greenberg SM. Beta-amyloid, blood vessels, and brain function. Stroke 2009;40:2601–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown WR, Thore CR. Review: cerebral microvascular pathology in ageing and neurodegeneration. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2011;37:56–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frost S, Kanagasingam Y, Sohrabi H, et al. Retinal vascular biomarkers for early detection and monitoring of Alzheimer’s disease. Transl Psychiatry 2013;3:e233–e233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenfeld PJ, Durbin MK, Roisman L, et al. Zeiss Angioplex™ spectral domain optical coherence tomography angiography: technical aspects. Dev Ophthalmol 2016;56:18–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bulut M, Kurtuluş F, Gözkaya O, et al. Evaluation of optical coherence tomography angiographic findings in Alzheimer’s type dementia. Br J Ophthalmol 2018;102:233–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang H, Wei Y, Shi Y, et al. Altered macular microvasculature in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. J Neuro-Ophthalmology 2017;38:292–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mckhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association workgroup. Alzheimer’s Dement 2011;7:263–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albert MS, Dekosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement 2011;7:270–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koronyo Y, Biggs D, Barron E, et al. Retinal amyloid pathology and proof-of-concept imaging trial in Alzheimer’s disease. JCI insight 2017;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Durbin MK, An L, Shemonski ND, et al. Quantification of retinal microvascular density in optical coherence tomographic angiography images in diabetic retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol 2017;135:370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Triolo G, Rabiolo A, Shemonski ND, et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography macular and peripapillary vessel perfusion density in healthy subjects, glaucoma suspects, and glaucoma patients. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2017;58:5713–5722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masters BR. Fractal analysis of the vascular tree in the human retina. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 2004;6:427–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams MA, McGowan AJ, Cardwell CR, et al. Retinal microvascular network attenuation in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement Diagnosis, Assess Dis Monit 2015;1:229–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haritoglou C, Rudolph G, Hoops JP, et al. Retinal vascular abnormalities in CADASIL. Neurology 2004;62:1202–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikram MK, Cheung CY, Wong TY, Chen CPLH. Retinal pathology as biomarker for cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012;83:917–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Carlo TE, Romano A, Waheed NK, Duker JS. A review of optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA). Int J Retin Vitr 2015;1:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henkind P Radial peripapillary capillaries of the retina. I. Anatomy: human and comparative. Br J Ophthalmol 1967;51:115–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Bryhim B, RS A, Kung N, et al. Association of preclinical alzheimer disease with optical coherence tomographic angiography findings. JAMA Ophthalmol 2018; doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.3556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fujiwara A, Morizane Y, Hosokawa M, et al. Factors affecting foveal avascular zone in healthy eyes: an examination using swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography González-Méijome JM, ed. PLoS One 2017;12:e0188572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghassemi F, Mirshahi R, Bazvand F, et al. The quantitative measurements of foveal avascular zone using optical coherence tomography angiography in normal volunteers. J Curr Ophthalmol 2017;29:293–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cunha LP, Lopes LC, Costa-Cunha LVF, et al. Macular thickness measurements with frequency domain-OCT for quantification of retinal neural loss and its correlation with cognitive impairment in Alzheimer disease. PLoS One 2016;11:e0153830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.den Haan J, Verbraak FD, Visser PJ, et al. Retinal thickness in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimer’s Dement (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2018;10:49–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cunha JP, Proença R, Dias-Santos A, et al. OCT in Alzheimer’s disease: thinning of the RNFL and superior hemiretina. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2017;255:1827–1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee CS, Larson EB, Gibbons LE, et al. Associations between recent and established ophthalmic conditions and risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement 2018;doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.06.2856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin I-C, Wang Y-H, Wang T-J, et al. Glaucoma, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease: an 8-year population-based follow-up study. PLoS One 2014;9:e108938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guedes V, Schuman JS, Hertzmark E, et al. Optical coherence tomography measurement of macular and nerve fiber layer thickness in normal and glaucomatous human eyes. Ophthalmology 2003;110:177–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blanks JC, Torigoe Y, Hinton DR, Blanks RH. Retinal pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. I. Ganglion cell loss in foveal/parafoveal retina. Neurobiol Aging 1996;17:377–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams PA, Thirgood RA, Oliphant H, et al. Retinal ganglion cell dendritic degeneration in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 2013;34:1799–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu S, Ong Y-T, Hilal S, et al. The association between retinal neuronal layer and brain structure is disrupted in patients with cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis 2016;54:585–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leite MT, Rao HL, Weinreb RN, et al. Agreement among spectral domain optical coherence tomography instruments for assessing retinal nerve fiber layer thickness. Am J Ophthalmol 2011;151:85–92.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Curcio CA, Allen KA. Topography of ganglion cells in human retina. J Comp Neurol 1990;300:5–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Larrieu S, Letenneur L, Orgogozo JM, et al. Incidence and outcome of mild cognitive impairment in a population-based prospective cohort. Neurology 2002;59:1594–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mufson EJ, Binder L, Counts SE, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: pathology and mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol 2012;123:13–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cunha JP, Moura-Coelho N, Proença RP, et al. Alzheimer’s disease: a review of its visual system neuropathology. Optical coherence tomography—a potential role as a study tool in vivo. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2016;254:2079–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aizenstein HJ, Nebes RD, Saxton JA, et al. Frequent amyloid deposition without significant cognitive impairment among the elderly. Arch Neurol 2008;65:1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Okello A, Koivunen J, Edison P, et al. Conversion of amyloid positive and negative MCI to AD over 3 years: an 11C-PIB PET study. Neurology 2009;73:754–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.